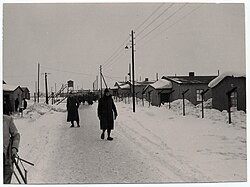

Stalag VIII-Awas a GermanWorld War IIprisoner-of-war camp,located just to the south of the town ofGörlitzinLower Silesia,east of theRiver Neisse.The location of the camp lies in today's Polish town ofZgorzelec,which lies over the river from Görlitz.

| Stalag VIII-A | |

|---|---|

| Görlitz(Zgorzelec),Lower Silesia | |

| |

| Coordinates | 51°07′17″N15°00′36″E/ 51.12152°N 15.01002°E |

| Type | Prisoner-of-war camp |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Site history | |

| In use | 1939–1945 |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | Polish POWs and civilians, Belgian, French, Soviet, British, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, South African, Italian, Yugoslav, Slovak, American and other Allied POWs |

It was originally set up as aHitler Jugend(Hitler Youth) camp, converted in October 1939 to housePolishprisoners (both soldiers and civilians), and later held up to 30,000Alliedprisoners of war (POWs), including Belgians, theFrench,Soviets,Britons, Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans,Italians,Yugoslavs, Slovaks and Americans, before its evacuation in February 1945. Its most famous inmate was French composerOlivier Messiaen.

Camp history

editOriginally aHitler Youthcamp, in October 1939 it was modified to house about 15,000Polishprisoners from the GermanSeptember 1939offensive. It was established on August 26, 1939, a few days before the Germaninvasion of Poland,which startedWorld War II.[1]It was initially a transit camp orDulaglocated on an 18-hectare field alongside Ulica Lubańska, renamed as Stalag VIII–A on 23 September 1939. Polish POWs who were either deported west to Germany or sent to nearbyforced laboursubcamps were held in the camp.[1]The first 8,000 Polish POWs were brought to the camp on September 7, 1939.[2]It also served as a transit camp for Polish civilians, including women, as well as activists andintelligentsiafromSilesia,Greater PolandandPomerania,who were arrested during theIntelligenzaktionto be deported toNazi concentration campsin Germany.[2]At the end of December 1939 the prisoners were transferred to the main camp inUjazd(then officiallyMoys), located on the right side of the road from Görlitz toBogatynia(then officiallyReichenau). Poor sanitary conditions led to frequent epidemic outbreaks in the camp.[3]Around 3,000 people were held in the camp, while 7,000 were sent to forced labour subcamps in the region.[4]Most of the over 10,000 prisoners were Poles, others includedCzechs,Lithuanians,BelarusiansandJews.[2]It was the first prisoner of war camp in the military district VIII Breslau (Wroclaw). The camp covered about 30 ha.[5]

By June 1940 most of the Poles had been transferred to other camps and replaced withBelgianandFrenchtroops taken prisoner during theBattle of France.Due to the lack of infrastructure, the French and Belgians were held in tents in mid-1940.[6]At one time there were over 30,000 jammed into facilities designed for 15,000.[7]In 1941 a separate compound was created to houseSovietprisoners. Over 1,500 Jews were deported from the camp toLublininGerman-occupied Polandin 1941, and last Poles were deported from the camp in 1942.[8]In 1943, 2,500British Commonwealthsoldiers came from the battles inItaly,among them residents from the British Isles,Canada,Australia,New ZealandandSouth Africa.Later in the same year more than 6,000Italiansoldiers came fromAlbania.A total of 47,328, the highest number of prisoners in Stalag VIII A was registered in September 1944. Numerically, Frenchmen were in the majority, followed by theRussians,Italians, Belgians,Britonsand theYugoslavs.[5]In late 1944, 37 Poles, participants of theWarsaw Uprising,and 1,500 Slovaks from theSlovak National Uprisingwere brought to the camp.[8]Finally in late December 1944 1,800Americansarrived, captured in theBattle of the Bulge.Soviet and Italian POWs suffered the worst sanitary conditions and were deprived of medical care.[9]French paramedics helped them temporarily, however, there was a high mortality rate among them.[9]In April 1945, 217 ill Polish POWs were brought fromTangerhütteto Stalag VIII-A.[10]

On 14 February 1945 the Americans and British were marched out of the camp westward in advance of the Sovietoffensiveinto Germany.[11]The evacuation process was carried out gradually through to May 1945. The evacuation took place on foot, with all means of transport driving in front of the people for military purposes.The Long Marchclaimed further victims. Some of the prisoners were taken toBavaria,others toThuringia,where they were freed by the Allies. The last evacuation of the camp took place on 7 May 1945, when the Soviet army freed the prisoners.[5]

After the war, many graves of western soldiers were exhumed and sent back to their home countries. In 1948 the city council of Zgorzelec decided to have the barracks dismantled in order to use the materials to rebuild Warsaw and other Polish towns.[5]

In 1976 a memorial was erected on the site of the former commandant’s office by French and Polish veterans who had been POWs. On the sandstone plate next to the memorial it says:Stalag VIIIA: A place sanctified by the blood and martyrdom of the prisoners of war of the anti-Hitler coalition during the Second World War – 22.VII.1976French veterans of the camp arranged for a marble slab to be attached to the memorial in 1994. On the slab it says in Polish and French:“1939 Stalag VIIIA 1945: Through this camp walked, in it lived and suffered ten thousands of prisoners of war”.[5]

Forced labour subcamps

editThere were numerous forced labour camps subordinate to Stalag VIII-A, located in various places throughout Lower Silesia. In 1943 there were 976 such camps.[12]Locations includeDaubitz,Kowary,Legnica,Przełęcz Karkonoska,Raszowa,Strzegom,StrzelinandWałbrzych.[13][14][15]

Notable inmates

editIt was at VIII-A that the 31-year old composer and medicOlivier Messiaen,a French prisoner, finished composingQuatuor pour la fin du temps,his most famous work, a piece ofchamber music.With the help of a friendly German guard (Carl-Albert Brüll), he acquired manuscript paper and pencils, and was able to befriend three other POWs (violinist Jean le Boulaire, clarinettistHenri Akoka,and cellistÉtienne Pasquier). Together they premiered the work at the camp hall on 15 January 1941.[16][17]

Legacy

editIn 2011 the Germanalternative rockbandTopictodaydedicated their Song "Helden ohne Namen" ( "Heroes without Names" ) to the POWs of the camp, especially to Olivier Messiaen.[18][19][20][21]

In 2014 a German-Polish joint project, the Meeting Point Music Messiaen e.V., built a European cultural centre near the site of the former POW camp Stalag VIII-A. The idea of building a European Center of Education and Culture for children, the youth, artists, musicians and all the people of the European trinational region in this important place for European history emerged in December 2004. The role of the centre is not only to be a memorial place, but to give room for development and a broad range of artistic activities and creative development.[22]A map and detailed history of Stalag VIII-A can be found on the website.[5]

In September 2017, the centre hosted a conference entitledStalag VIIIA and European memory of The Second World War POWs.[23]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^abLusek, Joanna; Goetze, Albrecht (2011). "Stalag VIII A Görlitz. Historia – teraźniejszość – przyszłość".Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny(in Polish).34.Opole: 27.

- ^abcLusek, Goetze, p. 28

- ^Lusek, Goetze, p. 29

- ^Lusek, Goetze, p. 30

- ^abcdef"Stalag VIII A".Meetingpoint Music Messiaen e.V.2 May 2019.Retrieved27 May2020.

- ^Lusek, Goetze, p. 31

- ^"German Camps –British & Commonwealth Prisoners of war 1939-45".Discover The Military Ancestor In Your Family With Forces War Records.3 June 2019.Retrieved27 May2020.

- ^abLusek, Goetze, p. 33

- ^abLusek, Goetze, p. 36

- ^Lusek, Goetze, p. 45

- ^"Stalag VIIIA".pegasusarchive.org.2006.Retrieved17 May2012.

- ^Lusek, Goetze, p. 41

- ^Lusek, Goetze, pp. 43–45

- ^Przerwa, Tomasz (2020). "Zatrudnienie jeńców belgijskich, francuskich i radzieckich przy budowie Drogi na Przełęcz Karkonoską (Spindlerpaßstraße) 1940–1942".Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny(in Polish).43.Opole: 8–9.ISSN0137-5199.

- ^Bartkowski, Zbigniew (1972). "Obozy pracy przymusowej i obozy jenieckie na Ziemi Jeleniogróskiej w latach 1939–1945".Rocznik Jeleniogórski(in Polish). Vol. X. Wrocław:Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.p. 101.

- ^Ross, Alex (March 22, 2004)."The Rest Is Noise: Messiaen's Quartet for the End of Time".The New Yorker.Retrieved17 May2012.

- ^Brown, Kellie D. (2020).The sound of hope: Music as solace, resistance and salvation during the holocaust and world war II.McFarland.ISBN978-1-4766-7056-0.

- ^"Ein Rocksong über das Leiden der Kriegsgefangenen".Sächsische.de(in German). 26 May 2020.Retrieved4 August2022.

- ^Touristbüro i-vent (7 April 2020)."Oliver Messiaen" Quatour Pour La Fin Du Temps "Sonntag 15. Januar 2012; 19.00 Uhr".Touristbüro i-vent(in German). Archived fromthe originalon 27 May 2020.Retrieved4 August2022.

- ^Redakcja (9 January 2012)."Zgorzelec: Koncert na Stalagu".Zgorzelec Nasze Miasto(in Polish).Retrieved4 August2022.

- ^"Der" Meeting Point Music Messaien "in Gorlitz".SAEK gGmbH.Archived fromthe originalon 4 June 2017.

- ^"European Center Memory, Education, Culture".Meetingpoint Music Messiaen e.V.17 April 2020.Retrieved27 May2020.

- ^"Stalag VIII A and European memory of The Second World War POWs".Meetingpoint Music Messiaen e.V.22 September 2017.Retrieved27 May2020.

Further reading

edit- "Kriegsgefangenenlager STALAG VIII A in Zgorzelec-Ujazd (Görlitz-Moys)".gedenkplaetze.info(in German). Archived fromthe originalon 4 June 2016.

- McMullen, John William (2010).The Miracle of Stalag 8A: Beauty Beyond the Horror: Olivier Messiaen and the Quartet for the End of TimeBird Brain Productions.ISBN978-0982625521On Goodreads

- Mason, Walter Wynne. "7 — The Italian Armistice (July–December 1943). II: Transit and Permanent Camps in Germany and Austria". In Kippenberger, Howard Karl (ed.).Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45 Prisoners of War.Originally published by Historical Publications Branch, 1954; online 2016. Victoria University of Wellington.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Rischin, Rebecca (2006).For the End of Time: The Story of the Messiaen Quartet(New ed.). Cornell University Press.ISBN978-0-8014-7297-8.

- "Stalag VIII A – the former international POW camp".Europejskie Centrum Pamięć, Edukacja, Kultura.11 January 2013.Includes photos.

- Tattersall, Peter."Excerpts from diary of Captain Peter Tattersall R.A.M.C."Indiana Military Org.

Community project websites

edit- "Stalag 8A Prisoner of War Camp in the Second World War 1939-1945".The Wartime Memories Project.

- "Stalag VIIIA".pegasusarchive.org.