Sinitic languages

| Sinitic | |

|---|---|

| Chinese | |

| Ethnicity | Sinitic peoples |

| Geographic distribution | East Asia,Southeast Asia,Central Asia,North Asia |

| Linguistic classification | Sino-Tibetan

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Sinitic |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-5 | zhx |

| Glottolog | sini1245(Sinitic) macr1275(Macro-Bai) |

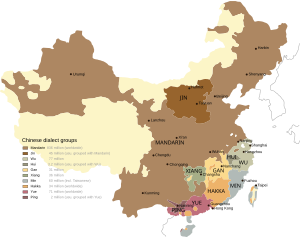

Map of Sinitic languages in China and Taiwan | |

TheSinitic languages[a](simplified Chinese:Hán ngữ tộc;traditional Chinese:Hán ngữ tộc;pinyin:Hànyǔ zú), often synonymous with theChinese languages,are agroupof East Asiananalytic languagesthat constitute a major branch of theSino-Tibetan language family.It is frequently proposed that there is a primary split between the Sinitic languages and the rest of the family (theTibeto-Burman languages). This view is rejected by some researchers[4]but has found phylogenetic support among others.[5][6]TheMacro-Bai languages,whose classification is difficult, may be an offshoot ofOld Chineseand thus Sinitic;[7]otherwise, Sinitic is defined only by the manyvarieties of Chineseunified by a shared historical background, and usage of the term "Sinitic" may reflect the linguistic view thatChineseconstitutes a family of distinct languages, rather than variants of a single language.[b]

Population

[edit]Over 91% of the Chinese population speaks a Sinitic language.[9]Approximately 1.52 billion people are speakers of the Chinese macrolanguage, of whom about three-quarters speak a Mandarin variety. Estimates of the number of global speakers of Sinitic branches as of 2018–2019, both native and non-native, are listed below:[10]

| Branch | Speakers | pct. |

|---|---|---|

| Mandarin | 1,118,584,040 | 73.50% |

| Yue | 85,576,570 | 5.62% |

| Wu | 81,817,790 | 5.38% |

| Min | 75,633,810 | 4.97% |

| Jin | 47,100,000 | 3.09% |

| Hakka | 44,065,190 | 2.90% |

| Xiang | 37,400,000 | 2.46% |

| Gan | 22,200,000 | 1.46% |

| Huizhou | 5,380,000 | 0.35% |

| Pinghua | 4,130,000 | 0.27% |

| Dungan | 56,300 | 0.004% |

| Total | 1,521,943,700 | 100% |

Languages

[edit]

DialectologistJerry Normanestimated that there are hundreds of mutually unintelligible Sinitic languages.[11]They form adialect continuumin which differences generally become more pronounced as distances increase, though there are also some sharp boundaries.[12]The Sinitic languages can be divided into Macro-Bai languages and Chinese languages, and the following is one of many potential ways of subdividing these languages. Some varieties, such asShaozhou Tuhua,are hard to classify and thus are not included in the following briefs.

Macro-Bai languages

[edit]This is a language family first proposed by linguistZhengzhang Shangfang,[13]and was expanded to include Longjia and Luren.[14][15]It likely split off from the rest of Sinitic during theOld Chineseperiod.[16]The languages included are all considered minority languages in China and are spoken in theSouthwest.[17][18]The languages are:

All other Sinitic languages henceforth would be considered Chinese.

Chinese

[edit]The Chinese branch of the family is classified into at least seven main families. These families are classified based on five main evolutionary criteria:[9]

- The evolution of the historical fully muddy (Toàn trọc;Toàn trọc;quánzhuó) initials

- The distribution of rimes across the four tone qualities, as conditioned by voicing and aspiration of initials

- The evolution of the checked (Nhập;rù) tone category

- The loss or retention of coda position plosives and nasals

- The palatalisation of thejiàninitial (Kiến mẫu;jiànmǔ) in front of high vowels

The varieties within one family may not be mutually intelligible with each other. For instance,WenzhouneseandNingboneseare not highly mutually intelligible. TheLanguage Atlas of Chinaidentifies ten groups:[19]

with Jin, Hui, Pinghua, and Tuhua not part of the seven traditional groups.

Mandarin

[edit]Varieties of Mandarin are used in theWestern Regions,theSouthwest,Huguang,Inner Mongolia,Central Plainsand theNortheast,[19]by around three-quarters of the Sinitic-speaking population.[10]Historically, the prestige variety has always been Mandarin, which is still reflected today inStandard Chinese.[20]Standard Chinese is now an official language of theRepublic of China,People's Republic of China,SingaporeandUnited Nations.[9]Re-population efforts, such as that of theQing dynastyin the Southwest, tended to involve Mandarin speakers.[21]Classification of Mandarin lects has undergone several significant changes, though nowadays it is commonly divided as such, based on the distribution of the historical checked tone:[19]

- Northeastern

- Beijing(sometimes considered part of Northeastern)[22][23]

- Jiaoliao(sometimes "Peninsular" )

- Jilu(sometimes "Northern" )

- Central Plains(or "Zhongyuan" )

- Lanyin(sometimes "Northwestern" and considered part of Central Plains)

- Jin(often considered a top-level group due to theLanguage Atlas of China)

- Southwestern(sometimes "Upper Yangtse" )

- Jianghuai(or "Lower Yangtze", sometimes "Huai", "Southern" or "Southeastern" )[20]

as well as other lects, which do not neatly fall into these categories, such as MandarinJunhuavarieties.

Varieties of Mandarin can be defined by their universally lost -m final, low number of tones, and smaller inventory ofclassifiers,among other features. Mandarin lects also often have rhoticerhuarimes, though the amount of its use may vary between lects.[9]Loss of checked tone is an often cited criterion for Mandarin languages, though lects such as Yangzhounese and Taiyuannese show otherwise.

| Mandarin | Non-Mandarin | Gloss | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | Jinan | Zhengzhou | Xi'an | Taiyuan | Chengdu | Nanjing | Guangzhou | Meizhou | Xiamen | Anyi | ||

| Âm | in | iẽ | iən | iẽ | iəŋ | in | in | iɐm | im | im | im | 'sound' |

| Tâm | ɕin | ɕiẽ | siən | ɕiẽ | ɕiəŋ | ɕin | sin | sɐm | sim | sim | ɕim | 'heart' |

Northeastern and Beijing Mandarin

[edit]Northeastern Mandarin is spoken inHeilongjiang,Jilin,most ofLiaoningand northeasternInner Mongolia,whereas Beijing Mandarin is spoken in northernHebei,most ofBeijing,parts ofTianjinandInner Mongolia.[19]The two families' most notable features are the heavy use ofrhoticerhuaand seemingly random distribution of the dark checked tone, and generally having four tones with the contours of high flat, rising, dipping, and falling.

| Northeastern/Beijing | Other | Gloss | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harbin | Changchun | Shenyang | Beijing | Heyuan | Chaozhou | Suzhou | Hefei | Wuhan | ||

| Khách | ˨˩˧ | ˥˧ | ˨˩˧ | ˥˧ | ˥ | ˨˩ | ˥˥ | ˥ | ˨˩˧ | 'guest' |

| Bát | ˦˦ | ˦˦ | ˧˧ | ˥˥ | ˥ | ˨˩ | ˥˥ | ˥ | ˨˩˧ | 'eight' |

| Bắc | ˨˩˧ | ˨˩˧ | ˨˩˧ | ˨˩˧ | ˥ | ˨˩ | ˥˥ | ˥ | ˨˩˧ | 'north' |

Northeastern Mandarin, especially in Heilongjiang, contains many loanwords from Russian.[24]

| Term | Pronunciation | Meaning | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bặc lưu khắc | bǔliúkè | 'rutabaga' | брюкваbryukva |

| Mã thần | mǎshén | 'machine' | машинаmashina |

| Ba li tử | bālízi | 'jail' | полицияpolitsiya |

Northeastern Mandarin lects can be divided into three main groups, namely Hafu (includingHarbinneseandChangchunnese), Jishen (includingJilinneseandShenyangnese), and Heisong. Notably, the extinctTaz languageofRussiais also a Northeastern Mandarin language. Beijing is sometimes included in Northeastern Mandarin due to its distribution of the historical dark checked tone,[22][23]though is listed as its own group by others, often due to its more regular light checked tones.[19]

Jilu Mandarin

[edit]Jilu Mandarin is spoken in southern Hebei and westernShandong,[19]and is often represented withJinannese.[25]Notable cities that use Jilu Mandarin lects includeCangzhou,Shijiazhuang,JinanandBaoding.[26][27]Characteristically Jilu Mandarin features include merging the dark checked into the dark level tone, the light checked into light level or departing based on themanner of articulationof theinitial,and vowel breaking intongrime series' (Thông nhiếp) checked-tone words, among other features.

Jilu Mandarin can be classified into Baotang, Shiji, Canghui and Zhangli.[28]Zhangli is of note due to its preservation of a separate checked tone.

Jiaoliao Mandarin

[edit]

Jiaoliao Mandarin is spoken in theJiaodongandLiaodong Peninsulae,which includes the cities ofDalianandQingdao,as well as several prefectures along the China-Korea border.[19]Like Jilu Mandarin, its light checked tone is merged into light level or departing based on the manner of articulation of the initial, though its dark checked is merged into the rising. Itsrìinitial (Nhật mẫu) terms are pronounced with anull initial(apart from openzhǐrime series (Chỉ nhiếp khai khẩu) finals), unlike the/ʐ/of Northern and Beijing Mandarin.[29]

Based on, for example, the pronunciation of thepalatalizedjiàninitial (Kiến mẫu),[19]Jiaoliao Mandarin can be divided into Qingzhou, Denglian and Gaihuan areas.[28]

| Yantai | Weihai | Qingdao | Dalian | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giao | ciau | ciau | tɕiɔ | tɕiɔ | 'to hand in' |

| Kiến | cian | cian | tɕiã | tɕiɛ̃ | 'to see' |

Central Plains and Lanyin Mandarin

[edit]Central Plains Mandarin is spoken in theCentral PlainsofHenan,southwesternShanxi,southernShandongand northernJiangsu,as well as most ofShaanxi,southernNingxiaandGansuand southernXinjiang,in famous cities such asKaifeng,Zhengzhou,Luoyang,Xuzhou,Xi'an,XiningandLanzhou.[30][31][32]Central Plains Mandarin lects merge the historical checked tones with a lesser muddy (Thứ trọc) and clear (Thanh) initial together with the rising tone, and those with a fully muddy (Toàn trọc) initial are merged with the light level tone.[19]

Lanyin Mandarin, spoken in northern Ningxia, parts of Gansu, and northern Xinjiang, is sometimes grouped with Central Plains Mandarin due to its merged lesser light and dark checked tones, though it is realised as a departing tone.

Subdivision of Central Plains Mandarin is not fully agreed upon, though one possible subdivision sees 13 divisions, namely Xuhuai, Zhengkai, Luosong, Nanlu, Yanhe, Shangfu, Xinbeng, Luoxiang, Fenhe, Guanzhong, Qinlong, Longzhong and Nanjiang.[33]Lanyin Mandarin, on the other hand, is divided as Jincheng, Yinwu, Hexi, and Beijiang. TheDungan languageis a collection of Central Plains Mandarin varieties spoken in the formerSoviet Union.

Jin

[edit]

Jin is spoken in most ofShanxi,westernHebei,northernShaanxi,northernHenanand centralInner Mongolia,[19]often represented byTaiyuannese.[25]It was first proposed as a lect separate from the rest of Mandarin byLi Rong,where it was proposed as lects in and around Shanxi with a checked tone, though this stance is not without disagreement.[34][35]Jin varieties also often has disyllabic words derived from syllable splitting ( phân âm từ ), through the infixation of/(u)əʔl/.[9]

Bổn

pəŋ꜄

→

Bạc

pəʔ꜇

Lăng

ləŋ꜄

'stupid'

Cổn

꜂kʊŋ

→

Cốt

kuəʔ꜆

Long

꜂lʊŋ

'to roll'

As per the Language Atlas by Li, Jin is divided into Dabao, Zhanghu, Wutai, Lüliang, Bingzhou, Shangdang, Hanxin, and Zhiyan branches.[19]

Southwestern Mandarin

[edit]Spoken inYunnan,Guizhou,northernGuangxi,most ofSichuan,southernGansuandShaanxi,Chongqing,most ofHubeiand bordering parts ofHunan,as well asKokangof Myanmar and parts of northernThailand,Southwestern Mandarin speakers take up the most area and population of all Mandarinic language groups, and would be the eighth most spoken language in the world if separated from the rest of Mandarin.[19]Southwestern Mandarinic tends to not haveretroflex consonants,and merges all checked tone categories together. Except forMinchi,which has a standalone checked category, the checked tone is merged with another category. Representative lects includeWuhanneseandSichuanese,and sometimesKunmingnese.[25]

Southwestern Mandarin tends to be split into Chuanqian, Xishu, Chuanxi, Yunnan, Huguang and Guiliu branches. Minchi is sometimes separated as a remnant of Old Shu.[36]

Huai

[edit]

Huai is spoken in centralAnhui,northernJiangxi,far western and easternHubeiand most ofJiangsu.[19]Due to its preservation of a checked tone, some linguists believe that Huai ought to be treated as a top-level group, like Jin. Representative lects tend to beNanjingnese,HefeineseandYangzhounese.[25]The Huai of Nanjing has likely served as a national prestige during the Ming and Qing periods,[37]though not all linguists support this viewpoint.[38]

The Language Atlas divides Huai into Tongtai, Huangxiao, and Hongchao areas, with the latter further split into Ninglu and Huaiyang. Tongtai, being geographically located furthest west, has the most significant Wu influence, such as in its distribution of historical voiced plosive series.[19][39][40]

| Tongtai | Non-Tongtai | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nantong | Taizhou | Yangzhou | Hangzhou | Fuzhou | Huizhou | |

| Địa | tʰi | tʰi | ti | di | tei | ti |

| Bệnh | pʰeŋ | pʰiŋ | pin | biŋ | paŋ | piaŋ |

Yue

[edit]

Yue Chinese is spoken by around 84 million people,[10]in westernGuangdong,easternGuangxi,Hong Kong,Macauand parts ofHainan,as well as overseas communities such asKuala LumpurandVancouver.[19]Famous lects such asCantoneseandTaishanesebelong to this family.[9]Yue Chinese lects generally possesslong-short distinctionsin their vowels, which is reflected in their almost universally split dark-checked and often split light-checked tones. They generally also tend to preserve all three checked plosive finals and three nasal finals. The status of Pinghua is uncertain, and some believe its two groups, Northern and Southern, should be listed under Yue,[41]though some reject this standpoint.[19]

| Tone | Dark | Light | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Long | Short | Long | |

| Examples | Bắc | Bát | Nhập | Bạch |

| Guangzhou | ˥˥ | ˧˧ | ˨˨ | |

| Hong Kong | ˥˥ | ˧˧ | ˨˨ | |

| Dongguan | ˦˦ | ˨˨˦ | ˨˨ | |

| Shiqi | ˥ | ˧ | ||

| Taishan | ˥˥ | ˧˧ | ˨˩ | |

| Bobai | ˥˥ | ˧˧ | ˨˨ | |

| Yulin | ˥ | ˧ | ˨ | ˨˩ |

Yue is generally split intoCantonese(which itself containsYuehai,Xiangshan, andGuanbao),Siyi,Gaoyang,Qinlian,Wuhua,Goulou(which includesLuoguang),Yongxunand the two Pinghua branches.[19]Siyi is generally agreed to be the most divergent, and Goulou is believed to be the one which is closest related to Pinghua.[41]

Hakka

[edit]Hakka Chinese is a direct result of several migration waves from Northern China to the South,[42]and is spoken in easternGuangdong,parts ofTaiwan,westernFujian,Hong Kong,southernJiangxi,as well as scattered points in the rest of Guangdong,Hunan,GuangxiandHainan,along with overseas communities such as inWest KalimantanandBangka Belitung IslandsinIndonesia,by an estimated total of 44 million people.[19][10]Some believe that Hakka is closely related to other groups, such as Gan, Yue, or Tongtai.[43][44][45]Hakka varieties generally have no voiced plosive initials and preserve the historicalrìinitial (Nhật mẫu) as an n-like sound.[19][46]

| Meizhou | Changting | Hsinchu | Hong Kong | Yudu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nhân | ȵin | neŋ | ȵin | ŋɡin | niẽ |

| Nhật | ȵit | ni | ȵit | ŋɡit | nie |

Hakka can be divided into Yuetai, Hailu, Yuebei, Yuexi, Tingzhou, Ninglong, Yuxin and Tonggui.[19]Meizhouneseis often used as the representative variety of Hakka.[25]

Min

[edit]

Min Chinese is a direct descendant of Old Chinese, and is spoken inChaoshanandZhanjiangofGuangdong, Hainan,Taiwan,most ofFujianand parts ofJiangxiandZhejiang,by around 76 million people.[10]Due to significant amounts of migration, many people inSoutheast AsiaandHong Kongare also able of speaking Min varieties. Lects such asTeoswa,Hainanese,Hokkien(incl.Taiwanese) andHokchiuare all Min varieties.[19]

Since Min descended from Old Chinese rather than Middle Chinese, it has some features that would be out of place in other varieties. For instance, some words with thechenginitial (Trừng mẫu) are not affricates in Min. This, interestingly, has led to many languages, such asOccitan,Inuktitut,Latin,MāoriandTelugu,loaning the Sinitic word for 'tea' (Trà) with a plosive. Min varieties also have a very large number of words withliterary pronunciations.[9]

| Min | Non-Min | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuzhou | Quanzhou | Chaozhou | Putian | Jian'ou | Haikou | Leizhou | Lanzhou | Guiyang | Changsha | |

| Trà | ta | te | te | tɒ | ta | ʔdɛ | te | tʂʰa | tsʰa | tsa |

| Trần | tiŋ | tan | tʰiŋ | tɛŋ | teiŋ | ʔdaŋ | taŋ | tʂʰən | tsʰən | tsən |

Min can primarily be split into Coastal and Inland Min varieties. The former contains theSouthern Minbranches of Quanzhang (Hokkien), Chaoshan (Teoswa),DatianandZhongshan,theEastern Minbranches of Houguan and Funing, Qionglei Min, as well asPuxian Min,whereas the latter includesNorthern,CentralandShaojiang Min.Shaojiang Min acts as a transitional area between Min, Gan, and Hakka.[20][34]

Wu

[edit]

Wu Chinese is spoken in most ofZhejiang,Shanghai,southernJiangsu,parts of southernAnhuiand easternJiangxiby around 82 million people.[19][10][47]Many large cities in theYangtze Delta,such asSuzhou,Changzhou,NingboandHangzhou,use a Wu variety. Wu varieties generally have a fricative initial in their negators, a three-way plosive distinction, as well as a checked coda preserved as aglottal stop,except for Oujiang lects, where it has becomevowel length,and Xuanzhou.[47][40]

| Shanghai | Suzhou | Changzhou | Shaoxing | Ningbo | Taizhou | Wenzhou | Jinhua | Lishui | Quzhou | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thông | tʰoŋ | tʰoŋ | tʰoŋ | tʰoŋ | tʰoŋ | tʰoŋ | tʰoŋ | tʰoŋ | tʰɔŋ | tʰaŋ |

| Đông | toŋ | toŋ | toŋ | toŋ | toŋ | toŋ | toŋ | toŋ | tɔŋ | taŋ |

| Đồng | doŋ | doŋ | doŋ | doŋ | doŋ | doŋ | doŋ | doŋ | dɔŋ | daŋ |

Shanghainese,SuzhouneseandWenzhouneseare usually used as representatives of Wu.[25]Wu Chinese varieties generally have a massive number of vowels, which rivals evenNorth Germanic languages.[48][49]TheDondac varietyhas been observed to have 20 phonemic monophthongal vowels, according to one analysis.[50]

Qian Nairongdivides Wu intoTaihu(or Northern Wu),Taizhou,Oujiang,ChuquandWuzhou.Northern Wu is further divided into Piling, Suhujia, Tiaoxi, Linshao, Yongjiang, and Hangzhou, though Hangzhou's classification is unclear.[40][47]

Hui

[edit]Huizhou Chinese is spoken in westernHangzhou,southernAnhuiand parts ofJingdezhen,by around 5 million people.[19][10]It is identified as a top-level group by the Language Atlas, though some linguists believe in other theories, such as it being a Gan-influenced Wu variety, due to an identifiable basis of Old Wu features.[9][51][52][53]Hui varieties are phonologically diverse, and some features are shared with Wu, such as the simplification of diphthongs.[54]Hui can be divided into Jishe, Xiuyi, Qiwu, Jingzhan and Yanzhou branches, with Tunxinese and Jixinese being representatives.

Gan

[edit]Gan Chinese is spoken in northern and centralJiangxi,parts ofHebeiandAnhuiand easternHunan,by 22 million people,[19][10]sometimes believed to be related to Hakka.[43][44]Gan varieties tend to notpalatalizeterms with thejianinitial (Kiến mẫu) and have an f-like initial in closedxiaoandxiainitial (Hợp khẩu hiểu hạp lưỡng mẫu) terms, among other features.[55]

| Nanchang | Yichun | Ji'an | Fuzhou | Yingtan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hôi | ϕɨi | fi | fei | fai | fɛi |

| Hồ | ϕu | fu | fu | fu | fu |

Gan can also be divided into Northern and Southern groups. The Northern group was formed during theTang dynasty,whereas the Southern group was developed based on Northern Gan.[9]The Language Atlas sees Gan divided into Changdu, Yiliu, Jicha, Fuguang, Yingyi, Datong, Dongsui, Huaiyue, and Leizi branches.[19]Nanchangneseis often chosen as the representative.[25]Shaojiang Min is identified to be influenced or even closely related to Fuguang Gan.[56]

Xiang

[edit]

Xiang Chinese is spoken in central and westernHunanand nearby parts ofGuangxiandGuizhouby an estimated 37 million people.[19][10]Due to migrations, Xiang can be split into New and Old Xiang groups, with Old Xiang having fewer Mandarin-influenced features.[57][9]Xiang varieties have universally lost their checked codas, but the majority of them still have a unique preserved checked tone contour. Most also have a three-way plosive distinction, like Wu varieties.[19]

One way of dividing Xiang varieties sees five distinct families, namely Changyi, Hengzhou, Louzhao, Chenxu, and Yongzhou.[58]Changshaneseand one ofShuangfengneseorLoudineseare usually taken as Xiang representatives.[25]

Internal classification

[edit]

The traditional, dialectological classification of Chinese languages is based on the evolution of the sound categories ofMiddle Chinese.Little comparative work has been done (the usual way of reconstructing the relationships between languages), and little is known about mutual intelligibility. Even within the dialectological classification, details are disputed, such as the establishment in the 1980s of three new top-level groups:Huizhou,JinandPinghua,although Pinghua is itself a pair of languages and Huizhou maybe half a dozen.[60][61]

Like Bai, theMinlanguages are commonly thought to have split off directly fromOld Chinese.[62]The evidence for this split is that all Sinitic languages apart from the Min group can fit into the structure of theQieyun,a 7th-centuryrime dictionary.[63]However, this view is not universally accepted.

Points of contention

[edit]Like many other language families, Sinitic languages have had problems with classification. The following are a few examples.

Southern China

[edit]Traditionally, thelect of urban HangzhouandNew Xiangof easternHunanare not considered Mandarin.[19]However, linguists such as Richard VanNess Simmons and Zhou Zhenhe have observed that these two varieties possess more qualifying features ofMandarinlanguages.[40][64]For instance, the vowels of the second division of thejia(Giả) initial is often raised and backed in Wu and Xiang, while they are not in Hangzhounese and New Xiang.

| Traditionally Mandarin | Traditionally Wu | Traditionally Xiang | Gloss | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | Nanjing | Nantong | Shanghai | Suzhou | Wenzhou | Hangzhou | Changsha | Shuangfeng | ||

| Hoa | xua | xuɑ | xuo | ho | ho | kʰo | hua | fa | xo | 'flower' |

| Qua | kua | kuɑ | kuo | ko | ko | ko | kua | kua | ko | 'melon' |

| Hạ | ɕia | ɕiɑ | xo | ɦo | ɦo | ɦo | ia | xa | ɣo | 'down' |

Nantongnese has heavy Wu influence, which has led to it also having raised and backed vowels.

DanzhouneseandMaihuaare both traditionally consideredYuelects.[19]Recent research, however, has noted that these are both are more likely unclassified.[65]Maihua, for example, may be a Yue-Hakka-Hainanese Minmixed language.[66]

Dongjiang Bendihua (Đông giang bổn địa thoại) is spoken in and aroundHuizhouandHeyuan.Its classification has always been unclear, though the most common standpoint is that it is considered Hakka.[19][67]

Northern China

[edit]The variety spoken in theGanyu DistrictofLianyungang(Cống du thoại) is listed as a variety ofCentral Plains Mandarinin theLanguage Atlas of China,[19]though its tonal distribution is more similar toPeninsular Mandarinvarieties.[68]

Relationships between groups

[edit]Jerry Normanclassified the traditional seven dialect groups into three larger groups: Northern (Mandarin), Central (Wu, Gan, and Xiang), and Southern (Hakka, Yue, and Min). He argued that the Southern Group is derived from a standard used in the Yangtze valley during theHan dynasty(206 BC – 220 AD), which he called Old Southern Chinese, while the Central group was transitional between the Northern and Southern groups.[69]Somedialect boundaries,such as between Wu and Min, are particularly abrupt, while others, such as between Mandarin and Xiang or between Min and Hakka, are much less clearly defined.[12]

Scholars account for the transitional nature of the central varieties in terms ofwave models.Iwata argues that innovations have been transmitted from the north across theHuai Riverto theLower Yangtze Mandarinarea and from there southeast to the Wu area and westwards along theYangtze Rivervalley and thence to southwestern areas, leaving the hills of the southeast largely untouched.[70]

A quantitative study

[edit]A 2007 study compared fifteen major urban dialects on the objective criteria oflexical similarityand regularity of sound correspondences, and subjective criteria of intelligibility and similarity. Most of these criteria show a top-level split with Northern,New Xiang,andGanin one group andMin(samples at Fuzhou, Xiamen, Chaozhou),Hakka,andYuein the other group. The exception was phonological regularity, where the one Gan dialect (Nanchang Gan) was in the Southern group and very close toMeixian Hakka,and the deepest phonological difference was betweenWenzhounese(the southernmost Wu dialect) and all other dialects.[71]

The study did not find clear splits within the Northern and Central areas:[71]

- Changsha (New Xiang) was always within the Mandarin group. No Old Xiang dialect was in the sample.

- Taiyuan (Jinor Shanxi) and Hankou (Wuhan, Hubei) were subjectively perceived as relatively different from other Northern dialects but were very close in mutual intelligibility. Objectively, Taiyuan had substantial phonological divergence but little lexical divergence.

- Chengdu (Sichuan) was somewhat divergent lexically but very little on the other measures.

The twoWu dialects(Wenzhou and Suzhou) occupied an intermediate position, closer to the Northern/New Xiang/Gan group in lexical similarity and strongly closer in subjective intelligibility but closer to Min/Hakka/Yue in phonological regularity and subjective similarity, except that Wenzhou was farthest from all other dialects in phonological regularity. The two Wu dialects were close to each other in lexical similarity and subjective similarity but not in mutual intelligibility, where Suzhou was closer to Northern/Xiang/Gan than to Wenzhou.[71]

In the Southern subgroup, Hakka and Yue grouped closely together on the three lexical and subjective measures but not in phonological regularity. The Min dialects showed high divergence, with Min Fuzhou (Eastern Min) grouped only weakly with theSouthern Mindialects ofXiamenandChaozhouon the two objective criteria and was slightly closer to Hakka and Yue on the subjective criteria.[71]

Internal comparison

[edit]The following section will be dedicated to comparing non-Bai and non-Cai–Long Sinitic languages. Though all stem from Old Chinese, they have all developed differences with each other.

Writing system

[edit]

Typographically, the vast majority of Sinitic languages useSinographs.However, some varieties, such asDunganandHokkien,have alternative scripts, namelyCyrillicandLatin alphabets.Even between varieties which use Sinographs, characters are repurposed or invented to cover for the difference in vocabulary. Examples includeTịnh;'pretty' in Yue,[72]𠊎;'I', 'me' in Hakka,[46]Tức;'this' in Hokkien,[73]Vật;'to not want' in Wu,[48]Mạc;'do not' in Xiang, andCa;'ill-tempered' in Mandarin.[74][24]Note that both traditional and simplified characters can be used to write any lect.

Phonology

[edit]Phonologically speaking, though all Sinitic languages possesstones,their contours and the total number of tones vary wildly, fromShanghainese,which can be analysed to have only two tones,[48]toBobainese,which has ten.[75]Sinitic languages also vary wildly in their phonological inventories and phonotactics. Take for instance/mɭɤŋ/(Môn nhi;'door (diminutive)') seen in Pingdingnese,[20]or/tʃɦɻʷəi/(Thủy;'water') of Xuanzhounese,[76]which both show syllables which do not follow the (single) consonant-glide-vowel-consonant syllable structure of more well-known lects. Tone sandhi is also a feature which not all lects share. Cantonese, for instance, only has a very weak system,[77]whereas Wu varieties not only have complex, intricate systems, which affect almost all syllables, but also uses it to mark for grammaticalpart of speech.[48][49]Take for instance, this simplified analysis of Suzhounese tone sandhi:[78]

| chain length → ↓ 1st char tone cat |

2 char | 3 char | 4 char |

|---|---|---|---|

| dark level (1) | ˦ ꜉ | ˦ ˦ ꜉ | ˦ ˦ ˦ ꜉ |

| light level (2) | ˨ ˧ | ˨ ˧ ꜊ | ˨ ˧ ˦ ꜉ |

| rising (3) | ˥ ˩ | ˥ ˩ ꜌ | ˥ ˩ ˩ ꜌ |

| dark departing (5) | ˥˨ ˧ | ˥˨ ˧ ꜊ | ˥˨ ˧ ˦ ꜉ |

| light departing (6) | ˨˧ ˩ | ˨˧ ˩ ꜌ | ˨˧ ˩ ˩ ꜌ |

| chain length → | 2 char | 3 char | 4 char | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd char tone cat |

1st char darkness | |||

| level (1, 2) | dark (7) | ˦ ˨˧ | ˦ ˨˧ ꜊ | ˦ ˨˧ ˦ ꜉ |

| light (8) | ˨ ˧ | ˨ ˧ ꜊ | ˨ ˧ ˦ ꜉ | |

| rising (3) | dark (7) | ˥ ˥˩ | ˥ ˥˩ ꜌ | ˥ ˥˩ ˩ ꜌ |

| light (8) | ˨ ˥˩ | ˨ ˥˩ ꜌ | ˨ ˥˩ ˩ ꜌ | |

| departing (5, 6) | dark (7) | ˥ ˥˨˧ | ˥ ˥˨ ˧ | ˥ ˥˨ ˨ ˧ |

| light (8) | ˨ ˥˨˧ | ˨ ˥˨ ˧ | ˨ ˥˨ ˨ ˧ | |

| checked (7, 8) | dark (7) | ˦ ˦ | ˦ ˦ ꜉ | ˦ ˦ ˦ ˨ |

| light (8) | ˧ ˦ | ˧ ˦ ꜉ | ˧ ˦ ˨ ꜋ | |

Grammar

[edit]Disregarding phonology, grammar is the feature of Sinitic languages which differ the most. The majority of Sinitic languages do not possess tenses, though exceptions include Northern Wu lects such as Shanghainese andSuzhounese,though it is largely breaking down in Shanghainese due to Mandarin influence.[49][79]Sinitic languages generally also have no case marking, though lects such as Linxianese and Hengshannese do possess case particles, with the latter expressing it through tone change.[80][81]Sinitic languages generally have SVO word order and possess classifiers.

Verb usage may be different between Sinitic languages. Notice the double verb marking seen in lects such asBeijingese,in these sentences meaning "today I go to Guangzhou":[82]

Indirect object marking

[edit]Sinitic languages tend to vary greatly in how they mark indirect objects. The area which varies tends to be the placement of the indirect and direct objects.[9][20]

Mandarinic, Xiang, Hui, and Min languages often place the indirect object (IO) before the direct object (DO). Some lects have switched to IO-DO structure due to Mandarin influence, such asNanchangeseandShanghainese,though Shanghainese also has the alternative word order.

|

Beijingese: Tha tā 3SG Cấp gěi give Liễu le PERF Ngã wǒ 1SG Nhất yī one Hạp hé CL Đường. táng sweets "He gave me a box of sweets." |

Taiyuanese: Cấp kei53 give Ngã ɣə53 1SG Nhất iəʔ2 one Bổn pəŋ53 CL Thư. su11 book "Give me a book."

|

|

Changshanese: Mụ mụ ma33ma ma Ai, ei SPEC Bả pa41 give Ngã ŋo41 1SG Lưỡng lian41 two Khối kʰuai41 CL Tiền tɕiɛ̃13 money Lạc. lo SPEC "Mama, give me two dollars please." |

Nanchangese: Nhĩ nhân ꜂n len 2SG.POL Tiếp ꜀tɕia lend Liễu le PERF Cừ ꜂tɕie 3SG Tam ꜀san three Chỉ tsaʔ꜆ CL Oa. ꜀wo pot "You lent him three pots."

|

On the other hand, Gan, Wu, Hakka, and Yue languages tend to place the DO in front of the IO.

|

Yichunnese: Ngã ŋo34 1SG Đắc tɛ42⁻33 give Bổn pun42 CL Thư ɕy34 book Nhĩ. ȵi34 2SG "I give a book to you." |

|

|

Yining Pinghua: Phân fɐn34 give Cá ko33 CL Lê tử lɐi31tsə53 pear Nhĩ. nə53 2SG "I'll give you a pear." |

Hong Kong Hakka (Lau's Romanization):[83] Phân bín give Khối kuài CL Diện bao mèn báu bread 𠊎. ngāi 1SG "Give me a piece of bread."

|

Classifiers

[edit]Like other East Asian languages such asJapaneseandKorean,Sinitic languages have a system ofclassifers,however, use of classifiers vary greatly in features such asdefiniteness.[20]In Cantonese, for instance, they can be used to mark possession, which is rare in Sinitic while common in Southeast Asia.[9]

Ngã

ngo5

1SG

Bổn

bun2

CL

Thư

syu1

book

'my book'

CáandChỉare the most common generic classifiers cross-linguistically.[9]As previously mentioned, Mandarinic languages tend to have fewer classifiers whereas the Southern non-Mandarinic varieties tend to have more.[20]

Demonstratives

[edit]Sinitic languages can vary greatly in their system ofdemonstratives.[20]Standard Mandarinand other Northeastern varieties have a two-way system:Giá;zhè(proximal) andNa;nà(distal), but this is not the only system found in Sinitic languages.

Wuhannesehas a neutral demonstrative, which can be used regardless of the distance to the deictic center.[84][85]Similar systems are found in Northern Wu lects such as Suzhounese andNingbonese.[49][20]

In the above sentence,/nɤ³⁵/can be translated as both 'this' and 'that'. Though Wuhannese has this system of a one-term neutral system, it also has a two-way proximal-distal system. This is the same for most other lects with a one-term system.

Even within two-way systems, which is the most common system, terms could have developed to mean the opposite distance from the deitic center. Cantonese嗰;go²(distal) and ShanghaineseCách;geq(proximal) are both etymologically fromCá,for instance.[72][48]

Many Sinitic languages have three-way systems, but the three distances are not always the same ones. For instance, whereas Guangshan Mandarin has a person-oriented proximal, medial, and distal system, Xinyu Gan has a distance-oriented close, proximal, and distal system. Gan especially has many varieties with a three-way system, sometimes even marked with tone and vowel length rather than just changing the term used.[20][86]

A small number of varieties possess even four- or five-term demonstrative systems. Take for instance the following:[20]

| Dongxiang | Zhangshu | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | ꜀ko | kọ꜆ |

| Proximal | ꜁ko | ko꜆ |

| Distal | ꜀e | ꜃hɛ |

| Yonder | ꜁e | ꜃hɛ̣ |

These two lects use tone change and vowel length respectively to distinguish between the four demonstratives.

Notes

[edit]- ^From Late LatinSīnae,'the Chinese', probably from ArabicṢīn'China', from the Chinese dynastic nameQin.(OED). In 1982,Paul K. Benedictproposed a subgroup of Sino-Tibetan called "Sinitic" comprisingBaiand Chinese.[1]The precise affiliation of Bai remains uncertain[2]and the termSiniticis usually used as a synonym for Chinese, especially when viewed as a language family rather than as a language.[3]

- ^SeeEnfield (2003:69) andHannas (1997)for examples. The Chinese terms often translated as 'language' and 'dialect' do not correspond well to those translations. These areNgữ ngôn;yǔyán,corresponding tomacrolanguageorlanguage cluster,which is used for Chinese itself;Phương ngôn;fāngyán,which separates mutually unintelligible languages within ayǔyán;andThổ ngữ;tǔyǔorThổ thoại;tǔhuà,which corresponds better to the familiar Western linguistic use of 'dialect'.[8]

- ^abThis term was not assigned a character.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^Wang (2005),p. 107.

- ^Wang (2005),p. 122.

- ^Mair (1991),p. 3.

- ^van Driem (2001),p. 351.

- ^Zhang, Menghan; Yan, Shi; Pan, Wuyun; Jin, Li (2019). "Phylogenetic evidence for Sino-Tibetan origin in northern China in the Late Neolithic".Nature.569(7754): 112–115.Bibcode:2019Natur.569..112Z.doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1153-z.ISSN1476-4687.PMID31019300.S2CID129946000.

- ^Sagart et al. (2019).

- ^van Driem (2001:403) states "Bái... may form a constituent of Sinitic, albeit one heavily influenced by Lolo–Burmese. "

- ^Bradley (2012),p. 1.

- ^abcdefghijklmChan, Sin-Wai; Chappell, Hilary; Li, Lan (2017). "Mandarin and other Sinitic languages".Routledge Encyclopedia of the Chinese language.Oxford: Routledge. pp. 605–628.

- ^abcdefghi"Chinese".

- ^Norman (2003),p. 72.

- ^abNorman (1988),pp. 189–190.

- ^Zhengzhang, Shangfang (2010).Thái gia thoại bạch ngữ quan hệ cập từ căn bỉ giác.Nghiên cứu chi nhạc(in Chinese) (2). Shanghai Educational Publishing House: 389–400.

- ^Quý châu tỉnh dân tộc thức biệt công tác đội ngữ ngôn tổ (1984).Thái gia đích ngữ ngôn(in Chinese).

- ^Quý châu tỉnh dân tộc thức biệt công tác đội (1984).Nam long nhân ( nam kinh - long gia ) tộc biệt vấn đề điều tra báo cáo.

- ^Gong, Xun (6 November 2015). "How Old is the Chinese in Bái?". Paris.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^Quý châu tỉnh chí dân tộc chí.Guiyang: Quý châu dân tộc xuất bản xã. 2002.

- ^Xu, Lin; Zhao, Yansun (1984).Bạch ngữ giản chí(in Chinese). Dân tộc ấn xoát hán.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeLi, Rong (2012).Trung quốc ngữ ngôn địa đồ tập.

- ^abcdefghijkChappell, Hilary M. (2015).Diversity in Sinitic Languages.Oxford University Press.ISBN9780198723790.

- ^Tsung, Linda (2014).Language Power and Hierarchy: Multilingual Education in China.Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ^abLin, Tao (1987). "Bắc kinh quan thoại khu đích hoa phân".Phương ngôn(3): 166–172.ISSN0257-0203.

- ^abZhang, Shifang (2010).Bắc kinh quan thoại ngữ âm nghiên cứu.Beijing Language and Culture University Press.ISBN978-7-5619-2775-5.

- ^abYin, Shichao (1997).Cáp nhĩ tân phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã.

- ^abcdefghBắc kinh đại học trung quốc ngữ ngôn văn học hệ (1995).Hán ngữ phương ngôn từ hối.Ngữ văn xuất bản xã.

- ^Wu, Jizhang; Tang, Jianxiong; Chen, Shujing (2005).Hà bắc tỉnh chí phương ngôn chí.Phương chí xuất bản xã.

- ^Qian, Zengyi (2002). "Sơn đông phương ngôn nghiên cứu" (3).

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^abQian, Zengyi (2010).Hán ngữ quan thoại phương ngôn nghiên cứu.Tề lỗ thư xã.

- ^Luo, Futeng (1997).Mưu bình phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã.

- ^He, Wei (June 1993).Lạc dương phương ngôn nghiên cứu.Xã hội khoa học văn hiến xuất bản xã.

- ^Su, Xiaoqing; Lü, Yongwei (December 1996).Từ châu phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã.ISBN7534328837.

- ^Zhang, Chengcai (December 1994).Tây ninh phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã.ISBN7534322936.

- ^He, Wei.Trung nguyên quan thoại phân khu.Beijing: Trung quốc xã hội khoa học viện ngữ ngôn nghiên cứu sở.

- ^abHou, Jing (2002).Hiện đại hán ngữ phương ngôn khái luận.Thượng hải giáo dục xuất bản xã. p. 46.

- ^Wang, Futang (1998).Hán ngữ phương ngôn ngữ âm đích diễn biến hòa tằng thứ.Beijing: Ngữ văn nghiên cứu.

- ^Zhou, Jixu (2012). "Nam lộ thoại hòa hồ quảng thoại đích ngữ âm đặc điểm".Ngữ ngôn nghiên cứu(3).

- ^Hán ngữ phương ngôn học đại từ điển.Quảng đông giáo dục xuất bản xã. 2017. p. 150.ISBN9787554816332.

- ^Zeng, Xiaoyu (2014). "《 tây nho nhĩ mục tư 》 âm hệ cơ sở phi nam kinh phương ngôn bổ chứng".Ngữ ngôn khoa học(4).

- ^Tao, Guoliang.Nam thông phương ngôn từ điển.Nanjing: Giang tô nhân dân xuất bản xã.

- ^abcdRichard VanNess Simmons (1999).Chinese Dialect Classification: A comparative approach to Harngjou, Old Jintarn, and Common Northern Wu.John Benjamins Publishing Co.

- ^abLin, Yi (2016). "Quảng tây đích việt phương ngôn".Khâm châu học viện học báo.31(6): 38–42.

- ^"The Hakka People > Historical Background".edu.ocac.gov.tw.Archived fromthe originalon 2019-09-09.Retrieved2010-06-11.

- ^abPeng, Xinyi (2010).Giang tây khách cống ngữ đích đặc thù âm vận hiện tượng dữ kết cấu biến thiên.Quốc lập trung hưng đại học trung quốc văn học nghiên cứu sở.

- ^abLu, Guoyao (2003).Lỗ quốc nghiêu ngữ ngôn học luận văn tập · khách, cống, thông thái phương ngôn nguyên ô nam triều thông ngữ thuyết.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã. pp. 123–135.ISBN7534354994.

- ^Sagart, Lawrence (March 2011).Chinese dialects classified on shared innovations.

- ^abHuang, Xuezhen (December 1995).Mai huyện phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã.ISBN7534325064.

- ^abcQian, Nairong (1992).Đương đại ngô ngữ nghiên cứu.Thượng hải giáo dục xuất bản xã.

- ^abcdeQian, Nairong (2007).Thượng hải thoại đại từ điển.Thượng hải giáo dục xuất bản xã.

- ^abcdYe, Changling (1993).Tô châu phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã.

- ^"Phụng hiền kim hối học giáo thủ khai" dịch thái thoại "Khóa ( đồ )".Nhân dân võng.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-07-22.Retrieved2022-07-22.

- ^Li, Rulong (2001).Hán ngữ phương ngôn học.Beijing: Cao đẳng giáo dục xuất bản xã. p. 17.

- ^Zhengzhang, Shangfang (1986). "Hoàn nam phương ngôn đích phân khu ( cảo )".Phương ngôn(1).

- ^Zhang, Guangyu (1999). "Đông nam phương ngôn quan hệ tổng luận".Phương ngôn(1).

- ^Meng, Qinghui (2005).Huy châu phương ngôn.Beijing: An huy nhân dân xuất bản xã.

- ^Sun, Yizhi; Chen, Changyi; Xu, Yangchun (2001).Giang tây cống phương ngôn ngữ âm đích đặc điểm.

- ^Chen, Zhangtai.Mân ngữ nghiên cứu.

- ^Song, Diwu; Cao, Shuji.Trung quốc di dân sử đệ ngũ quyển: Danh sư kỳ.

- ^Bao, Houxing; Chen, Hui (2005).Tương ngữ đích phân khu ( cảo ).

- ^Sagart et al. (2019),pp. 10319–10320.

- ^Kurpaska (2010),pp. 41–53, 55–56.

- ^Yan (2006),pp. 9–18, 61–69, 222.

- ^Mei (1970),p.?.

- ^Pulleyblank (1984),p. 3.

- ^Zhou, Zhenhe; You, Rujie (1986).Fāngyán yǔ zhōngguó wénhuàPhương ngôn dữ trung quốc văn hóa[Dialects and Chinese culture]. Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe.

- ^Kurpaska (2010),p. 73.

- ^Jiang, Ouyang & Zou (2007)

- ^Liu, Ruoyun (1991).Huệ châu phương ngôn chí.

- ^Liu, Chuanxian (2001).Cống du phương ngôn chí.Beijing: Trung hoa thư cục.

- ^Norman (1988),pp. 182–183.

- ^Iwata (2010),pp. 102–108.

- ^abcdTang & Van Heuven (2007),p. 1025.

- ^abBai, Wanru (1998).Quảng châu phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã xuất bản.ISBN9787534334344.

- ^Li, Rong (1993).Hạ môn phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã xuất bản.ISBN9787534319952.

- ^Bao, Houxing (December 1998).Trường sa phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã xuất bản.ISBN9787534319983.

- ^Xie, Jianyou (2007).Quảng tây hán ngữ phương ngôn nghiên cứu.Quảng tây nhân dân xuất bản xã.

- ^Shen, Ming (2016).An huy tuyên thành ( nhạn sí ) phương ngôn.Trung quốc xã hội khoa học xuất bản xã.

- ^Zheng, Ding'ou (1997).Hương cảng việt ngữ từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã.ISBN9787534329425.

- ^Wang, Ping (August 1996).Tô châu phương ngôn ngữ âm nghiên cứu.Hoa trung lý công đại học xuất bản xã.ISBN7560911315.

- ^Qian, Nairong ( tiền nãi vinh ) (2010).《 tòng 〈 hỗ ngữ tiện thương 〉 sở kiến đích lão thượng hải thoại thời thái 》 (Tenses and Aspects? Old Shanghainese as Found in the Book Huyu Bian Shang).Shanghai: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

- ^Zhang, Qiang (2021). "Lâm hạ phương ngôn cách tiêu ký “Cáp [XA⁴³]” tham cứu ".Hoài nam sư phạm học viện học báo.23(2). Guangzhou.

- ^Liu, Juan; Peng, Zerun (July 2019). "Hành sơn phương ngôn nhân xưng đại từ lĩnh cách biến điều hiện tượng đích thật chất".Tương đàm đại học học báo ( triết học xã hội khoa học bản ).43(4).

- ^Liu, Danqing (2001).Ngô ngữ đích cú pháp loại hình đặc điểm.

- ^Lau, Chun-Fat (November 2021).Hương cảng khách gia thoại nghiên cứu.Hong Kong: Trung hoa giáo dục.ISBN9789888760046.

- ^Zhu, Jiansong (1992).Võ hán phương ngôn nghiên cứu.

- ^Zhu, Jiansong (May 1995).Võ hán phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã.ISBN7534323290.

- ^Wei, Gangqiang (1995).Lê xuyên phương ngôn từ điển.Giang tô giáo dục xuất bản xã.

- Sagart, Laurent;Jacques, Guillaume;Lai, Yunfan; Ryder, Robin; Thouzeau, Valentin; Greenhill, Simon J.; List, Johann-Mattis (2019), "Dated language phylogenies shed light on the history of Sino-Tibetan",Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,116(21): 10317–10322,doi:10.1073/pnas.1817972116,PMC6534992,PMID31061123.

- "Origin of Sino-Tibetan language family revealed by new research".ScienceDaily(Press release). May 6, 2019.

Works cited

[edit]- Bradley, David (2012), "Languages and Language Families in China", in Rint Sybesma (ed.),Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics.,Brill

- Enfield, N. J. (2003),Linguistics Epidemiology: Semantics and Language Contact in Mainland Southeast Asia,Psychology Press,ISBN0415297435

- Hannas, W. (1997),Asia's Orthographic Dilemma,University of Hawaii Press,ISBN082481892X

- Iwata, Ray (2010),"Chinese Geolinguistics: History, Current Trend and Theoretical Issues",Dialectologia,Special issue I: 97–121.

- Jiang, Huo giang địch; Ouyang, Jueya âu dương giác á; Zou, Heyan trâu gia ngạn (2007), "Hǎinán Shěng Sānyà Shì Màihuà yīnxì"Hải nam tỉnh tam á thị mại thoại âm hệ,FāngyánPhương ngôn(in Chinese),2007(1): 23–34.

- Kurpaska, Maria (2010),Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of "The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects",Walter de Gruyter,ISBN978-3-11-021914-2

- Mair, Victor H.(1991),"What Is a Chinese 'Dialect/Topolect'? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic terms"(PDF),Sino-Platonic Papers,29:1–31.

- Mei, Tsu-lin(1970), "Tones and prosody in Middle Chinese and the origin of the rising tone",Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies,30:86–110,doi:10.2307/2718766,JSTOR2718766

- Norman, Jerry(1988),Chinese,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0-521-29653-3.

- Norman, Jerry(2003), "The Chinese dialects: Phonology", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.),The Sino-Tibetan languages,Routledge, pp. 72–83,ISBN978-0-7007-1129-1

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G.(1984),Middle Chinese: A study in Historical Phonology,Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press,ISBN978-0-7748-0192-8

- Tang, Chaoju; Van Heuven, Vincent J. (2007),"Predicting mutual intelligibility in chinese dialects from subjective and objective linguistic similarity"(PDF),Interlingüística,17:1019–1028.

- Thurgood, Graham (2003), "The subgroup of the Tibeto-Burman languages: The interaction between language contact, change, and inheritance", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.),The Sino-Tibetan languages,Routledge, pp. 3–21,ISBN978-0-7007-1129-1

- van Driem, George (2001),Languages of the Himalayas: An Ethnolinguistic Handbook of the Greater Himalayan Region,Brill,ISBN90-04-10390-2

- Wang, Feng (2005), "On the genetic position of the Bai language",Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale,34(1): 101–127,doi:10.3406/clao.2005.1728.

- Yan, Margaret Mian (2006),Introduction to Chinese Dialectology,LINCOM Europa,ISBN978-3-89586-629-6