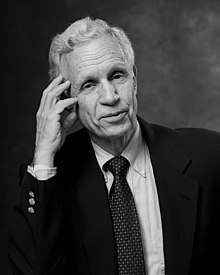

David Bevington

David Martin Bevington(May 13, 1931 – August 2, 2019) was an American literary scholar. He was the Phyllis Fay Horton Distinguished ServiceProfessor Emeritusin theHumanitiesand inEnglish Language & Literature,Comparative Literature,and the college at theUniversity of Chicago,where he taught since 1967, as well as chair of Theatre and Performance Studies.[1]"One of the most learned and devoted of Shakespeareans,"[2]so called byHarold Bloom,he specialized inBritish dramaof theRenaissance,and edited and introduced the complete works ofWilliam Shakespearein both the 29-volume,BantamClassics paperback editions and the single-volumeLongmanedition. After accomplishing this feat, Bevington was often cited as the only living scholar to have personally edited Shakespeare's complete corpus.

He also edited theNortonAnthology of Renaissance Drama and an important anthology of Medieval English Drama, the latter of which was just re-released by Hackett for the first time in nearly four decades.[3][4]Bevington's editorial scholarship is so extensive that Richard Strier, anearly moderncolleague at the University of Chicago, was moved to comment: "Every time I turn around, he has edited a new Renaissance text. Bevington has endless energy for editorial projects."[5]In addition to his work as aneditor,he published studies of Shakespeare,Christopher Marlowe,and theStuart CourtMasque,among others, though it is for his work as an editor that he is primarily known.

Despite formally retiring, Bevington continued to teach and publish. Most recently he authoredShakespeare and Biography,a study of the history of Shakespearean biography and of such biographers,[6]as well asMurder Most Foul: Hamlet Through the Ages.[7][8]In August, 2012, after a decade of research, he released the first complete edition of Ben Jonson published in over a half-century with Ian Donaldson and Martin Butler from the Cambridge Press.[9]In addition to his preeminence among scholars ofWilliam Shakespeare,he was a much beloved teacher, winning a Quantrell Award in 1979.

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]David Bevington was born to Merle M. (1900–1964) andHelen Bevington(néeSmith; 1906–2001), and grew up inManhattan,and from age eleven,North Carolina,when his parents, themselves both academics, finished graduate school atColumbia Universityand went on to join the faculty atDuke.After attendingPhillips Exeter Academyfrom 1945 to 1948, before it was co-educational, he graduated fromHarvard Universitycum laude in 1952, before entering thenavythat year, and becoming alieutenant junior gradebefore his leaving in 1955.[citation needed]He saw much of the Mediterranean, though neitherIsraelnorTurkey.[citation needed]Upon his return to Harvard, he pursued an M.A. and Ph.D., receiving them respectively in 1957 and 1959.[citation needed]Surprisingly, he was well into the graduate process before settling on theRenaissance;he had intended to study theVictorianuntil a Shakespeare seminar convinced him otherwise.

Teaching and fellowships

[edit]During the doctoral process, he was a teaching fellow at Harvard. When he was granted the final degree, his title changed to instructor. He held this post until 1961, when he became assistant professor of english at theUniversity of Virginia;he then became associate professor in 1964, and professor in 1966. In 1967, he was a visiting professor at the University of Chicago for a year, and joined the faculty as professor in 1968. In 1985 he was appointed to the Phyllis Fay Horton distinguished service professorship in the humanities, a post he held continuously thereafter.

In 1963, he served as visiting professor at New York University's summer school; he filled that capacity at Harvard's summer school in 1967, at the University of Hawaii in 1970, and at Northwestern University in 1974.

In 1979, Bevington was honored with the Llewellyn John and Harriet Manchester Quantrell Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching.[10]The Quantrell Award, for which students of the college nominate their instructors, is considered among the highest accolades the University of Chicago confers, and the most treasured by the faculty.

Bevington served as senior consultant and seminar leader at the Folger Institute inRenaissanceand 18th-century Studies from 1976 to 1977 and 1987–88. He has had twoGuggenheim fellowships,first in 1964–65, and again in 1981–82. He was a senior fellow at the Southeastern Institute of Medieval and Renaissance Studies during the summer of 1975. He was appointed the 2006-2007 Lund-Gill Chair in Rosary College of Arts and Sciences atDominican UniversityinRiver Forest, Illinois.

Consistently, Bevington was the instructor of a two-part History and Theory of Drama sequence.[11]This course was co-taught with actor/translatorNicholas Rudall,dramaturg Drew Dir, director of undergraduate studies in theater and performance studies Heidi Coleman, and actor David New.[12]It is now taught by Professor John Muse, a transition which first occurred when Bevington chose to decrease his teaching hours and focus on Shakespeare-centric classes. The first quarter of this course spans drama from Greek drama to the Renaissance. The second quarter begins withIbsen'sA Doll's Houseand ends with thepostmodern,includingBeckett'sEndgameand the work ofPinterand Caryl Churchill. For midterms and finals, students either write a paper critically analyzing a play, or else perform scenes from plays relevant to the course (though not necessarily those read in class). Bevington required, from those opting to perform, a reflection paper analyzing the challenges of staging the scene.

Bevington also taught courses entitled "Shakespeare: Histories and Comedies," surveying such plays asRichard II,Richard III,Henry IV, Part 1,Henry V,Much Ado About Nothing,A Midsummer Night's Dream,Twelfth Night,andMeasure for Measure;[13]"Shakespeare: Tragedies and Romances"; and "Shakespeare's History Plays"; among others. When Bevington was not instructing these courses, they were often led by his fellow professors Richard Strier, John Muse, or Tim Harrison. Bevington usually spent Spring Quarter with B.A. theses he advised, and the corresponding students, or else traveled. However, he was also known to sign up for introductory-level courses in subjects vastly different from his own (such as Greek, or the Natural Sciences).

When possible, Bevington opted to teach class in the large Edward M. Sills Seminar Room, which features a large, oval table accommodating several dozen, rather than in a more traditional classroom in which all the students might face a lectern.[14]He felt this format fosters greater participation and discussion among students, and went out of his way to encourage the sharing of ideas and opinions. However, because so many students elected to take his popular classes, the room at times became overfull.

He taught a number of other courses:

- Shakespeare at the Opera (with the late scholarPhilip Gossett)

- SkepticismandSexualityin Shakespeare

- The Young Shakespeare and the Drama that he Knew

- Shakespeare in the Mediterranean

- British Theatre (in 2003, during the London study-abroad program the English Department offered every autumn)

- Renaissance Drama (which paired five Shakespeare plays with five other plays)

Memberships and honors

[edit]Bevington was elected a Fellow of theAmerican Academy of Arts and Sciencesin 1985,[15]and a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1986.[16]

He belonged to a number of academic organizations:

- American Association of University Professors(acting president, Virginia conference, 1962–63, president, 1963–64)

- Shakespeare Association of America (president, 1976–77, 1995–96)

- Renaissance English Text Society (president, 1978–present)[17]

- Modern Language Associationof America

- Renaissance Society of America

Personal life

[edit]David and Margaret Bronson BevingtonnéeBrown ( "Peggy" ) were married on June 4, 1953. Peggy taught primary schoolchildren at the Laboratory School adjacent to the main quadrangles for many years. They lived several blocks from the University of Chicago's main campus, and threw a lightsoiréefor his students once perquarter.They had four children: Stephen Raymond, Philip Landon, Katharine Helen, and Sarah Amelia and five grandchildren, two of whom (Leo and Peter) attended the University of Chicago. Leo was an active member of the Dean's Men, a student performance group for which Bevington served as faculty advisor. In addition to attending all of the Dean's Men productions, Bevington hosted an event each quarter wherein he discussed the text with the cast and staff of the show at his home. Bevington self-identified as both aDemocratand "lapsedEpiscopalian."[18]Bevington's adamant support for exercise was demonstrated in his use of the bicycle as a means oftransportation,and when that was made impossible by snow or rain, in his insistence on walking (rather than driving) the requisite distance to campus. He notably also took public transportation whenever he traveled from hisHyde Parkhome to downtownChicago.Bevington was left-handed and a concertviolist,and he often performed in various ensembles, including aquartetinvolving faculty and students from the university. He enjoyedchamber musicand opera, and owned a restored pre-World War ISteinwaygrand piano.The Bevingtons celebrated their sixtieth ( "Diamond Jubilee" ) wedding anniversary on June 4, 2013, at a reception organized by the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts and the program for Theatre and Performance Studies, of which Bevington was formerly the faculty chair.

He died on August 2, 2019, at the age of 88.[19]Peggy died on September 5, 2020.

Selected bibliography

[edit]Although the following does not boast of being complete, it includes the vast majority of Bevington's publications sorted into three lists: books he has authored, plays/anthologies thereof he has edited, and anthologies of scholarly essays he edited (with or without a co-editor).

Authored

[edit]- From "Mankind" to Marlowe: Growth of Structure in the Popular Drama of Tudor England(Harvard University Press, 1962)

- Tudor Drama and Politics: A Critical Approach to Topical Meaning(Harvard University Press, 1968)

- Shakespeare(Goldentree Bibliographies in Language and Literature) AHM Pub. Corp., 1978.

- Action Is Eloquence: Shakespeare's Language of Gesture(Harvard University Press, 1984)

- Homo, Memento Finis: The Iconography of Just Judgment in Medieval Art and Drama(Early Drama, Art, and Music Monograph Series, 6). Western Michigan Univ Medieval Press. (1985)

- Shakespeare: The Seven Ages of Human Experience(Blackwell Publishing, 2002)

- The Theatrical City: Culture, Theatre and Politics in London, 1576-1649,with David L. Smith and Richard Strier (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

- Shakespeare: Script, Stage, Screen(Longman, 2005)

- How to Read a Shakespeare Play,part of theHow to Study Literatureseries (Wiley-Blackwell, 2006)

- This Wide and Universal Theater: Shakespeare in Performance, Then and Now(University of Chicago Press, 2007)

- Shakespeare's Ideas: More Things in Heaven and Earth(Wiley-Blackwell, 2008)

- Shakespeare and Biography(Oxford University Press, 2010)

- Murder Most Foul: Hamlet Through the Ages(Oxford, 2011)

- The Works of Ben Jonson(Cambridge, 2012)

As editor of drama

[edit]Bevington's extensive bibliography as an editor comprised mainly the Shakespeare canon and a complete Jonson. The bulk of his work was with David Scott Kastan in the 29-volume Bantam series, which was originally published in 1988 and was reissued in 2005, and his own complete Shakespeare, which is continually reissued. However, Bevington worked on a handful of plays for other publishers, though nearly all are within the scope of the English Renaissance. Bevington notably maintained a single, conflated text in all of his editions ofKing Lear,a revisionist choice criticized by some scholars (including the abovementioned Richard Strier, who insists his own students read the Quarto and Folio texts separately).

Bantam Classics

[edit]The Bantam Classics series, self-touted as "The most student-friendly Shakespeare on the market," is different from, for instance, Bevington's Oxford and Arden editions of Henry IV and Troilus and Cressida (respectively) in not so much scholarship, but intended audience. A high-school student finds Bantam straightforward, on the whole, because its glossary explains all words that might be obscure or different in meaning from their present use. The latter two, however, assume an audience already somewhat versed in the idiomatic dialect of Elizabethan England.

In addition to the many individual volumes listed below, there have been collected anthologies of Shakespeare plays. A few of these Bantam anthologies contain plays that are unavailable from Bantam in their solo form. The anthologies are as follows:

- Four Tragedies: Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth

- Four Comedies: The Taming of the Shrew, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Merchant of Venice, Twelfth Night

- The Late Romances:Pericles,Cymbeline,The Winter's TaleandThe Tempest

- Three Early Comedies: Love's Labour's Lost, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Merry Wives of Windsor

- Three Classical Tragedies: Titus Andronicus, Timon of Athens, Coriolanus

- Measure for Measure, All's Well that Ends Well, Troilus and Cressida (Note: Although not indicated as such in the title, the three plays contained herein are considered Shakespeare's 'problem plays,' and frequently grouped together as such.)

Furthermore, Bantam has published Bevington's edition of Shakespeare'ssonnetsand other poetry.

Comedies:

- The Comedy of Errors

- Much Ado About Nothing

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Twelfth Night

- The Merchant of Venice

- As You Like It

- The Taming of the Shrew

Romances:

Histories:

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI (all three parts contained in one volume)

- Richard II

- Richard III

- King JohnandHenry VIIIpublished as one volume.

Tragedies:

Longman

[edit]The Longman complete Shakespeare is unique because, unlike the Oxford, Riverside, Norton, or Arden (and the less impressive Pelican), it is edited by a single scholar. It furthermore contains certain obscure plays, such asThe Two Noble Kinsmen,that the Bantam series simply could not market. Its poetry selection is moreover wider than that of the Bantam series, containing the substantial work outside the sonnets.

- The Complete Works of Shakespeare,Portable Edition (2006)

- Shakespeare's Comedies,Bevington Shakespeare Series (2006)

- Shakespeare's Tragedies,Bevington Shakespeare Series (2006)

- Shakespeare's Histories,Bevington Shakespeare Series (2006)

- Shakespeare's Romances and Poems,Bevington Shakespeare Series (2006)

- The Complete Works of Shakespeare(6th edition, 2008)

- The Necessary Shakespeare(3rd edition, 2008)

Revels Plays and Student Editions

[edit]Although two separate entities, both series are published by Manchester University Press. David Bevington was a general editor of the Revels Plays.

- The New Inn(1984)

- The Jew of Malta(1997)

- Endymion(1997)

- Tamburlaine The Great(1999)

- Volpone(1999)

- Plays on Women:A Chaste Maid in Cheapside,The Roaring Girl,Arden of Faversham,andA Woman Killed With Kindness(1999)

- CampaspeandSappho and Phao(1999)

- Doctor Faustus(2nd Edition, 2007)

- GalateaandMidas(2008)

The Sourcebooks Shakespeare

[edit]The Sourcebooks Shakespeare is a series that includes an audio CD to enrich the otherwise purely textudal experience. The CD contains more than 60 minutes of audio narrated by Sir Derek Jacobi and includes version of key speeches from historical and contemporary productions. They are published by Sourcebooks, and Bevington served as advisory editor for the series.

Tragedies:

- Romeo and Juliet(2005)

- Julius Caesar(2006)

- Hamlet(2006)

- King Lear(2007)

- Othello(2005)

- Macbeth(2006)

Comedies and Romances:

- The Taming of the Shrew(2008)

- The Merchant of Venice(2008)

- A Midsummer Night's Dream(2005)

- Much Ado about Nothing(2006)

- The Tempest(2008)

Histories:

- Richard III(2007)

Others

[edit]David Bevington's work as editor of drama included several individual plays and anthologies not tied to any larger series. The Oxford, Cambridge, and Arden editions are significantly more scholarly than the Signet and above-mentioned Bantam plays; that is, the scholar assumes the reader to be somewhat versed in Elizabethan English such that the glossaries focus more on mythological and cultural references than mere syntax. They are recommended for graduate students and undergraduates.

- Medieval Drama,Wadsworth Publishing (1975)

- Richard II,Signet Classics (1999)

- Troilus and Cressida(Arden Shakespeare, 1998, revised 2016)

- English Renaissance Drama,A Norton Anthology (W.W. Norton & Co., 2002)

- Antony and Cleopatra(Cambridge University Press, 2005)

- The Spanish Tragedy(Methuen Drama, 2007)

- Doctor Faustusand Other Plays(Oxford University Press, 2008), a Marlowe collection leaving out anearly playwhose authenticity is controversial, and alate play,which has survived only fragmentally.

- Henry IV, Part 1,of Oxford World Classics'The Oxford Shakespeare(Oxford University Press, 2008)

- The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson

Other scholarship

[edit]As editor

[edit]- Twentieth Century Interpretations of Hamlet,Prentice Hall Trade (1968)[20][21]

- An Introduction to Shakespeare,Scott, Foresman (1975)[22]

- Shakespeare: Pattern of Excelling Nature,Associated University Presses (1978)[23][24]

- Henry IV, Parts I and II: Critical Essays,Garland (1986)[25]

- The Politics of the Stuart Court Masque,with Peter Holbrook (Cambridge University Press, 1998)[26]

As contributor

[edit]Books commemorating or dedicated to David Bevington

[edit]- David Bevington Remembered,compiled by Eric Rasmussen and Milla Cozart Riggio (BookArts of Washington, DC, 2020).

- Shakespeare and Montaigne,edited by Lars Engle, Patrick Gray, and William M. Hamlin (Edinburgh University Press, 2022).

References

[edit]- ^"Theater and Performance Studies | UChicago Arts | The University of Chicago".Taps.uchicago.edu.Archived fromthe originalon 2012-07-27.Retrieved2017-01-09.

- ^David Bevington (May 2009).This Wide and Universal Theater: Shakespeare in Performance, Then and Now.University of Chicago Press.ISBN9780226044798– via Amazon.com.

- ^"David Bevington".Aug 23, 2004. Archived fromthe originalon 2004-08-23.RetrievedAug 6,2019.

- ^David Bevington (2012).Medieval Drama.Hackett.ISBN9781603848381.

- ^"Bevington to repeat Ryerson Lecture".News.uchicago.edu.Retrieved2017-01-09.

- ^David Bevington (10 June 2010).Shakespeare and Biography (Oxford Shakespeare Topics).OUP Oxford.ISBN9780199586479– via Amazon.com.

- ^"Bevington, Fischer-Galati, Maskin, Nussbaum: The 2010 Centennial Medalists".Harvard Magazine. 2015-07-12.Retrieved2017-01-09.

- ^David Bevington (23 June 2011).Murder Most Foul: Hamlet Through the Ages.OUP Oxford.ISBN9780199599103– via Amazon.com.

- ^Ben Jonson; David Bevington; Martin Butler; Ian Donaldson.The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson 7 Volume Set.ISBN9780521782463.

- ^"Llewellyn John and Harriet Manchester Quantrell Awards for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching | The University of Chicago".Uchicago.edu.Archived fromthe originalon 2012-09-19.Retrieved2017-01-09.

- ^"Courses | Department of English Language and Literature"(PDF).English.uchicago.edu.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2017-01-10.Retrieved2017-01-09.

- ^"Heidi Coleman".Directory.uchicago.edu.Retrieved2017-01-09.

- ^"Courses | Department of English Language and Literature"(PDF).English.uchicago.edu.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2017-01-10.Retrieved2017-01-09.

- ^"University of Chicago Time Schedules".Timeschedules.uchicago.edu.Retrieved2017-01-09.

- ^"Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter B"(PDF).American Academy of Arts and Sciences.RetrievedJune 25,2011.

- ^"Public Profile: Dr. David M. Bevington".American Philosophy Society.Archived fromthe originalon March 19, 2012.RetrievedJune 25,2011.

- ^"Projects And Information: Library (1979) s6-I (4): 410"(PDF).Library.oxfordjournals.org.Retrieved2017-01-09.[dead link]

- ^Gale Reference Team. "Biography - Bevington, David M(artin) (1931-)." Contemporary Authors Online (Biography). Thomson Gale, 2005. Web. 11 Jan. 2010.

- ^"David Bevington (1931 -2019)".shaksper.net.RetrievedAug 6,2019.

- ^David M. Bevington (1968).Twentieth Century Interpretations of Hamlet: A Collection of Critical Essays (20th Century Interpretations).Prentice-Hall.ISBN9780133723755– via Amazon.com.

- ^David M. Bevington (1968).Twentieth century interpretations of Hamlet: a collection of critical essays.Prentice-Hall.Retrieved2017-01-09– viaInternet Archive.

- ^"Library Catalog".Jul 17, 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-07-17.RetrievedAug 6,2019.

- ^David Bevington; Jay Halio (1978).Shakespeare, Pattern of Excelling Nature: Shakespeare Criticism in Honor of...University of Delaware Press.ISBN9780874131291.Retrieved2017-01-09.

- ^David Bevington; Jay Halio.Shakespeare, Pattern of Excelling Nature: Shakespearean Criticism in Honor of America's Bicentennial.ISBN9780874131291– via Amazon.com.

- ^David Bevington (1986).Henry the Fourth Parts I and II: Critical Essays (Shakespearean criticism).Garland Pub.ISBN9780824087067– via Amazon.com.

- ^David Bevington; Peter Holbrook (2 November 2006).The Politics of the Stuart Court Masque.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521031202– via Amazon.com.

- ^David Klausner; Karen S. Marsalek (2007).'Bring furth the pagants': Essays in Early English Drama presented to Alexandra F. Johnston (Studies in Early English Drama).University of Toronto Press.ISBN9780802091079.Retrieved2017-01-09– via Amazon.com.

- ^David Klausner.'Bring furth the pagants¿.Search.barnesandnoble.com.Retrieved2017-01-09.

External links

[edit]- Bevington's homepageArchived2018-08-01 at theWayback Machineat the University of Chicago English Department website

- Bevington's homepageArchived2015-01-28 at theWayback Machineat the University of Chicago Comparative Literature website

- Video interviewThe Collected Works of Ben JonsonArchived2010-06-10 at theWayback Machine