Gastrointestinal tract

| Gastrointestinal tract | |

|---|---|

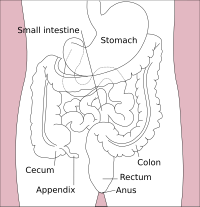

Diagram of the gastrointestinal tract in the averagehuman | |

| Details | |

| System | Digestive system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tractus digestorius (mouthtoanus), canalis alimentarius (esophagustolarge intestine), canalis gastrointestinalesstomachtolarge intestine) |

| MeSH | D041981 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| Major parts of the |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

|---|

Thegastrointestinal tract(GI tract,digestive tract,alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of thedigestive systemthat leads from themouthto theanus.The GI tract contains all the majororgansof the digestive system, in humans and other animals, including theesophagus,stomach,andintestines.Food taken in through the mouth isdigestedto extractnutrientsand absorbenergy,and the waste expelled at the anus asfaeces.Gastrointestinalis an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the stomach and intestines.

Most animalshave a "through-gut" or complete digestive tract. Exceptions are more primitive ones:spongeshave small pores (ostia) throughout their body for digestion and a larger dorsal pore (osculum) for excretion,comb jellieshave both a ventral mouth and dorsal anal pores, whilecnidariansandacoelshave a single pore for both digestion and excretion.[1][2]

The human gastrointestinal tract consists of theesophagus,stomach, and intestines, and is divided into the upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts.[3]The GI tract includes all structures between themouthand theanus,[4]forming a continuous passageway that includes the main organs of digestion, namely, thestomach,small intestine,andlarge intestine.The completehuman digestive systemis made up of the gastrointestinal tract plus the accessory organs of digestion (thetongue,salivary glands,pancreas,liverandgallbladder).[5]The tract may also be divided intoforegut,midgut,andhindgut,reflecting theembryologicalorigin of each segment. The whole human GI tract is about nine meters (30 feet) long atautopsy.It is considerably shorter in the living body because the intestines, which are tubes ofsmooth muscle tissue,maintain constantmuscle tonein a halfway-tense state but can relax in spots to allow for local distention andperistalsis.[6][7]

The gastrointestinal tract contains thegut microbiota,with some 1,000 differentstrainsofbacteriahaving diverse roles in the maintenance ofimmune healthandmetabolism,and many othermicroorganisms.[8][9][10]Cells of the GI tract releasehormonesto help regulate the digestive process. Thesedigestive hormones,includinggastrin,secretin,cholecystokinin,andghrelin,are mediated through eitherintracrineorautocrinemechanisms, indicating that the cells releasing these hormones are conserved structures throughoutevolution.[11]

Human gastrointestinal tract

[edit]Structure

[edit]

The structure and function can be described both asgross anatomyand asmicroscopic anatomyorhistology.The tract itself is divided into upper and lower tracts, and the intestinessmallandlargeparts.[12]

Upper gastrointestinal tract

[edit]The upper gastrointestinal tract consists of themouth,pharynx,esophagus,stomach,andduodenum.[13] The exact demarcation between the upper and lower tracts is thesuspensory muscle of the duodenum.This differentiates the embryonic borders between the foregut and midgut, and is also the division commonly used by clinicians to describegastrointestinal bleedingas being of either "upper" or "lower" origin. Upondissection,the duodenum may appear to be a unified organ, but it is divided into four segments based on function, location, and internal anatomy. The four segments of the duodenum are as follows (starting at the stomach, and moving toward the jejunum):bulb,descending, horizontal, and ascending. The suspensory muscle attaches the superior border of the ascending duodenum to thejejunum.

The suspensory muscle is an important anatomical landmark that shows the formal division between the duodenum and the jejunum, the first and second parts of the small intestine, respectively.[14]This is a thin muscle which is derived from theembryonicmesoderm.

Lower gastrointestinal tract

[edit]The lower gastrointestinal tract includes most of thesmall intestineand all of thelarge intestine.[15]Inhuman anatomy,theintestine(bowelorgut;Greek:éntera) is the segment of the gastrointestinal tract extending from the pyloric sphincter of thestomachto theanusand as in other mammals, consists of two segments: thesmall intestineand thelarge intestine.In humans, the small intestine is further subdivided into theduodenum,jejunum,andileumwhile the large intestine is subdivided into thececum,ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoidcolon,rectum,andanal canal.[16][17]

Small intestine

[edit]Thesmall intestinebegins at theduodenumand is a tubular structure, usually between 6 and 7 m long.[18]Itsmucosalarea in an adult human is about 30 m2(320 sq ft).[19]The combination of thecircular folds,the villi, and the microvilli increases the absorptive area of the mucosa about 600-fold, making a total area of about 250 m2(2,700 sq ft) for the entire small intestine.[20]Its main function is to absorb the products of digestion (including carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and vitamins) into the bloodstream. There are three major divisions:

- Duodenum:A short structure (about 20–25 cm long[18]) that receiveschymefrom the stomach, together withpancreatic juicecontainingdigestive enzymesandbilefrom thegall bladder.The digestive enzymes break down proteins, and bileemulsifiesfats intomicelles.TheduodenumcontainsBrunner's glandswhich produce a mucus-rich alkaline secretion containingbicarbonate.These secretions, in combination with bicarbonate from the pancreas, neutralize the stomach acids contained in the chyme.

- Jejunum:This is the midsection of the small intestine, connecting the duodenum to the ileum. It is about 2.5 m (8.2 ft) long and contains thecircular foldsalso known as plicae circulares andvillithat increase its surface area. Products of digestion (sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids) are absorbed into the bloodstream here.

- Ileum:The final section of the small intestine. It is about 3 m long, and containsvillisimilar to the jejunum. It absorbs mainlyvitamin B12andbile acids,as well as any other remaining nutrients.

Large intestine

[edit]Thelarge intestine,also called the colon, forms an arch starting at thececumand ending at therectumandanal canal.It also includes theappendix,which is attached to thececum.Its length is about 1.5 m, and the area of the mucosa in an adult human is about 2 m2(22 sq ft).[19]Its main function is to absorb water and salts. The colon is further divided into:

- Cecum(first portion of the colon) andappendix

- Ascending colon(ascending in the back wall of the abdomen)

- Right colic flexure(flexed portion of the ascending and transverse colon apparent to theliver)

- Transverse colon(passing below the diaphragm)

- Left colic flexure(flexed portion of the transverse and descending colon apparent to thespleen)

- Descending colon(descending down the left side of the abdomen)

- Sigmoid colon(a loop of the colon closest to the rectum)

- Rectum

- Anal canal

Development

[edit]The gut is anendoderm-derived structure. At approximately the sixteenth day of human development, theembryobegins to foldventrally(with the embryo's ventral surface becomingconcave) in two directions: the sides of the embryo fold in on each other and the head and tail fold toward one another. The result is that a piece of theyolk sac,anendoderm-lined structure in contact with theventralaspect of the embryo, begins to be pinched off to become the primitive gut. The yolk sac remains connected to the gut tube via thevitelline duct.Usually, this structure regresses during development; in cases where it does not, it is known asMeckel's diverticulum.

Duringfetallife, the primitive gut is gradually patterned into three segments:foregut,midgut,andhindgut.Although these terms are often used in reference to segments of the primitive gut, they are also used regularly to describe regions of the definitive gut as well.

Each segment of the gut is further specified and gives rise to specific gut and gut-related structures in later development. Components derived from the gut proper, including thestomachandcolon,develop as swellings or dilatations in the cells of the primitive gut. In contrast, gut-related derivatives — that is, those structures that derive from the primitive gut but are not part of the gut proper, in general, develop as out-pouchings of the primitive gut. The blood vessels supplying these structures remain constant throughout development.[21]

| Part | Part in adult | Gives rise to | Arterial supply |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foregut | esophagus to first 2 sections of the duodenum | Esophagus, stomach, duodenum (1st and 2nd parts), liver, gallbladder, pancreas, superior portion of pancreas (Though the spleen is supplied by theceliac trunk,it is derived from dorsal mesentery and therefore not a foregut derivative) |

celiac trunk |

| Midgut | lower duodenum, to the first two-thirds of the transverse colon | lowerduodenum,jejunum,ileum,cecum,appendix,ascending colon,and first two-thirds of thetransverse colon | branches of thesuperior mesenteric artery |

| Hindgut | last third of the transverse colon, to the upper part of the anal canal | last third of thetransverse colon,descending colon,rectum,and upper part of theanal canal | branches of theinferior mesenteric artery |

Histology

[edit]

The gastrointestinal tract has a form of general histology with some differences that reflect the specialization in functional anatomy.[22]The GI tract can be divided into four concentric layers in the following order:

Mucosa

[edit]The mucosa is the innermost layer of the gastrointestinal tract. The mucosa surrounds thelumen,or open space within the tube. This layer comes in direct contact with digested food (chyme). The mucosa is made up of:

- Epithelium– innermost layer. Responsible for most digestive, absorptive and secretory processes.

- Lamina propria– a layer of connective tissue. Unusually cellular compared to most connective tissue

- Muscularis mucosae– a thin layer ofsmooth musclethat aids the passing of material and enhances the interaction between the epithelial layer and the contents of the lumen by agitation andperistalsis

The mucosae are highly specialized in each organ of the gastrointestinal tract to deal with the different conditions. The most variation is seen in the epithelium.

Submucosa

[edit]The submucosa consists of a dense irregular layer of connective tissue with large blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves branching into the mucosa andmuscularis externa.It contains thesubmucosal plexus,anenteric nervous plexus,situated on the inner surface of themuscularis externa.

Muscular layer

[edit]Themuscular layerconsists of an inner circular layer and alongitudinalouter layer. The circular layer prevents food from traveling backward and the longitudinal layer shortens the tract. The layers are not truly longitudinal or circular, rather the layers of muscle are helical with different pitches. The inner circular is helical with a steep pitch and the outer longitudinal is helical with a much shallower pitch.[23]Whilst the muscularis externa is similar throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract, an exception is the stomach which has an additional inner oblique muscular layer to aid with grinding and mixing of food. The muscularis externa of the stomach is composed of the inner oblique layer, middle circular layer, and the outer longitudinal layer.

Between the circular and longitudinal muscle layers is themyenteric plexus.This controls peristalsis. Activity is initiated by the pacemaker cells, (myentericinterstitial cells of Cajal). The gut has intrinsic peristaltic activity (basal electrical rhythm) due to its self-contained enteric nervous system. The rate can be modulated by the rest of theautonomic nervous system.[23]

The coordinated contractions of these layers is calledperistalsisand propels the food through the tract. Food in the GI tract is called a bolus (ball of food) from the mouth down to the stomach. After the stomach, the food is partially digested and semi-liquid, and is referred to aschyme.In the large intestine, the remaining semi-solid substance is referred to asfaeces.[23]

Adventitia and serosa

[edit]The outermost layer of the gastrointestinal tract consists of several layers ofconnective tissue.

Intraperitonealparts of the GI tract are covered withserosa.These include most of thestomach,first part of theduodenum,all of thesmall intestine,caecumandappendix,transverse colon,sigmoid colonandrectum.In these sections of the gut, there is a clear boundary between the gut and the surrounding tissue. These parts of the tract have amesentery.

Retroperitonealparts are covered withadventitia.They blend into the surrounding tissue and are fixed in position. For example, the retroperitoneal section of the duodenum usually passes through thetranspyloric plane.These include theesophagus,pylorusof the stomach, distalduodenum,ascending colon,descending colonandanal canal.In addition, theoral cavityhas adventitia.

Gene and protein expression

[edit]Approximately 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and 75% of these genes are expressed in at least one of the different parts of the digestive organ system.[24][25]Over 600 of these genes are more specifically expressed in one or more parts of the GI tract and the corresponding proteins have functions related to digestion of food and uptake of nutrients. Examples of specific proteins with such functions arepepsinogen PGCand thelipase LIPF,expressed inchief cells,and gastricATPase ATP4Aandgastric intrinsic factor GIF,expressed inparietal cellsof the stomach mucosa. Specific proteins expressed in the stomach and duodenum involved in defence includemucinproteins, such asmucin 6andintelectin-1.[26]

Transit time

[edit]The time taken for food to transit through the gastrointestinal tract varies on multiple factors, including age, ethnicity, and gender.[27][28]Several techniques have been used to measure transit time, including radiography following abarium-labeled meal, breathhydrogenanalysis,scintigraphicanalysis following aradiolabeledmeal,[29]and simple ingestion and spotting ofcorn kernels.[30]It takes 2.5 to 3 hours for 50% of the contents to leave the stomach.[medical citation needed]The rate of digestion is also dependent of the material being digested, as food composition from the same meal may leave the stomach at different rates.[31]Total emptying of the stomach takes around 4–5 hours, and transit through the colon takes 30 to 50 hours.[29][32][33]

Immune function

[edit]The gastrointestinal tract forms an important part of theimmune system.[34]

Immune barrier

[edit]The surface area of the digestive tract is estimated to be about 32 square meters, or about half a badminton court.[19]With such a large exposure (more than three times larger than theexposed surface of the skin), these immune components function to prevent pathogens from entering the blood and lymph circulatory systems.[35]Fundamental components of this protection are provided by theintestinal mucosal barrier,which is composed of physical, biochemical, and immune elements elaborated by the intestinal mucosa.[36]Microorganisms also are kept at bay by an extensive immune system comprising thegut-associated lymphoid tissue(GALT)

There are additional factors contributing to protection from pathogen invasion. For example, lowpH(ranging from 1 to 4) of the stomach is fatal for manymicroorganismsthat enter it.[37]Similarly,mucus(containingIgAantibodies) neutralizes many pathogenic microorganisms.[38]Other factors in the GI tract contribution to immune function includeenzymessecreted in thesalivaandbile.

Immune system homeostasis

[edit]Beneficial bacteria also can contribute to the homeostasis of the gastrointestinal immune system. For example,Clostridia,one of the most predominant bacterial groups in the GI tract, play an important role in influencing the dynamics of the gut's immune system.[39]It has been demonstrated that the intake of a high fiber diet could be responsible for the induction ofT-regulatory cells(Tregs). This is due to the production ofshort-chain fatty acidsduring the fermentation of plant-derived nutrients such asbutyrateandpropionate.Basically, the butyrate induces the differentiation of Treg cells by enhancinghistone H3acetylationin the promoter and conserved non-coding sequence regions of theFOXP3locus, thus regulating theT cells,resulting in the reduction of the inflammatory response and allergies.

Intestinal microbiota

[edit]The large intestine contains multiple types ofbacteriathat can break down molecules the human body cannot process alone,[40]demonstrating asymbioticrelationship. These bacteria are responsible for gas production athost–pathogen interface,which is released asflatulence.However, the primary function of the large intestine is water absorption from digested material (regulated by thehypothalamus) and the reabsorption ofsodiumand nutrients.[41]

Beneficialintestinal bacteriacompete with potentially harmfulbacteriafor space and "food", as the intestinal tract has limited resources. A ratio of 80–85% beneficial to 15–20% potentially harmful bacteria is proposed for maintaininghomeostasis.[citation needed]An imbalanced ratio results indysbiosis.

Detoxification and drug metabolism

[edit]Enzymessuch asCYP3A4,along with theantiporteractivities, are also instrumental in the intestine's role ofdrug metabolismin the detoxification ofantigensandxenobiotics.[42]

Other animals

[edit]In mostvertebrates,includingfishes,amphibians,birds,reptiles,andegg-laying mammals,the gastrointestinal tract ends in acloacaand not ananus.In the cloaca, theurinary systemis fused with the genito-anal pore.Therians(all mammals that do not lay eggs, including humans) possess separate anal and uro-genital openings. The females of the subgroupPlacentaliahave even separate urinary and genital openings.

Duringearly development,the asymmetric position of the bowels and inner organs is initiated (see alsoaxial twist theory).

Ruminantsshow many specializations for digesting andfermentingtough plant material, consisting ofadditional stomach compartments.

Many birds and other animals have a specialised stomach in the digestive tract called agizzardused for grinding up food.

Another feature found in a range of animals is thecrop.In birds this is found as a pouch alongside the esophagus.

In 2020, the oldest known fossil digestive tract, of an extinct wormlike organism in theCloudinidaewas discovered; it lived during the lateEdiacaranperiodabout 550 million years ago.[43][44]

A through-gut (one with both mouth and anus) is thought to have evolved within thenephrozoanclade ofBilateria,after their ancestral ventral orifice (single, as incnidariansandacoels;re-evolved in nephrozoans likeflatworms) stretched antero-posteriorly, before the middle part of the stretch would get narrower and closed fully, leaving an anterior orifice (mouth) and a posterior orifice (anus plusgenital opening). A stretched gut without the middle part closed is present in another branch of bilaterians, the extinctproarticulates.This and theamphistomicdevelopment (when both mouth and anus develop from the gut stretch in the embryo) present in some nephrozoans (e.g.roundworms) are considered to support this hypothesis.[45][46]

Clinical significance

[edit]Diseases

[edit]There are many diseases and conditions that can affect the gastrointestinal system, includinginfections,inflammationandcancer.

Variouspathogens,such asbacteriathat causefoodborne illnesses,can inducegastroenteritiswhich results frominflammationof the stomach and small intestine.Antibioticsto treat such bacterial infections can decrease themicrobiomediversity of the gastrointestinal tract, and further enable inflammatory mediators.[47]Gastroenteritis is the most common disease of the GI tract.

- Gastrointestinal cancermay occur at any point in the gastrointestinal tract, and includesmouth cancer,tongue cancer,oesophageal cancer,stomach cancer,andcolorectal cancer.

- Inflammatory conditions.Ileitisis an inflammation of theileum,colitisis an inflammation of thelarge intestine.

- Appendicitisis inflammation of theappendixlocated at the caecum. This is a potentially fatal condition if left untreated; most cases of appendicitis require surgical intervention.

Diverticular diseaseis a condition that is very common in older people in industrialized countries. It usually affects the large intestine but has been known to affect the small intestine as well.Diverticulosisoccurs when pouches form on the intestinal wall. Once the pouches become inflamed it is known asdiverticulitis.

Inflammatory bowel diseaseis an inflammatory condition affecting the bowel walls, and includes the subtypesCrohn's diseaseandulcerative colitis.While Crohn's can affect the entire gastrointestinal tract, ulcerative colitis is limited to the large intestine. Crohn's disease is widely regarded as anautoimmune disease.Although ulcerative colitis is often treated as though it were an autoimmune disease, there is no consensus that it actually is such.

Functional gastrointestinal disordersthe most common of which isirritable bowel syndrome.Functional constipation andchronic functional abdominal painare other functional disorders of the intestine that have physiological causes but do not have identifiable structural, chemical, or infectious pathologies.

Symptoms

[edit]Several symptoms can indicate problems with the gastrointestinal tract, including:

- Vomiting,which may includeregurgitationof food or thevomiting of blood

- Diarrhea,or the passage of liquid or more frequent stools

- Constipation,which refers to the passage of fewer and hardened stools

- Blood in stool,which includesfresh red blood,maroon-coloured blood, andtarry-coloured blood

Treatment

[edit]Gastrointestinal surgerycan often be performed in the outpatient setting. In the United States in 2012, operations on the digestive system accounted for 3 of the 25 most common ambulatory surgery procedures and constituted 9.1 percent of all outpatient ambulatory surgeries.[48]

Imaging

[edit]Various methods of imaging the gastrointestinal tract include theupperandlower gastrointestinal series:

- Radioopaquedyes may be swallowed to produce abarium swallow

- Parts of the tract may be visualised by camera. This is known asendoscopyif examining the upper gastrointestinal tract andcolonoscopyorsigmoidoscopyif examining the lower gastrointestinal tract.Capsule endoscopyis where a capsule containing a camera is swallowed in order to examine the tract.Biopsiesmay also be taken when examined.

- Anabdominal x-raymay be used to examine the lower gastrointestinal tract.

Other related diseases

[edit]- Cholera

- Enteric duplication cyst

- Giardiasis

- Pancreatitis

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Yellow fever

- Helicobacter pyloriis agram-negativespiral bacterium. Over half the world's population is infected with it, mainly during childhood; it is not certain how the disease is transmitted. It colonizes the gastrointestinal system, predominantly the stomach. The bacterium has specific survival conditions that are specific to the human gastricmicroenvironment:it is bothcapnophilicandmicroaerophilic.Helicobacteralso exhibits atropismfor gastric epithelial lining and the gastric mucosal layer about it. Gastric colonization of this bacterium triggers a robust immune response leading to moderate to severeinflammation,known asgastritis.Signs and symptoms of infection are gastritis, burning abdominal pain, weight loss, loss of appetite, bloating, burping, nausea, bloody vomit, and black tarry stools. Infection can be detected in a number of ways: GI X-rays, endoscopy, blood tests for anti-Helicobacterantibodies, a stool test, and a urease breath test (which is a by-product of the bacteria). If caught soon enough, it can be treated with three doses of different proton pump inhibitors as well as two antibiotics, taking about a week to cure. If not caught soon enough, surgery may be required.[49][50][51][52]

- Intestinal pseudo-obstructionis a syndrome caused by a malformation of the digestive system, characterized by a severe impairment in the ability of the intestines to push and assimilate. Symptoms include daily abdominal and stomach pain, nausea, severe distension, vomiting, heartburn, dysphagia, diarrhea, constipation, dehydration and malnutrition. There is no cure for intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Different types of surgery and treatment managing life-threatening complications such as ileus and volvulus, intestinal stasis which lead to bacterial overgrowth, and resection of affected or dead parts of the gut may be needed. Many patients require parenteral nutrition.

- Ileusis a blockage of the intestines.

- Coeliac diseaseis a common form ofmalabsorption,affecting up to 1% of people of northern European descent. An autoimmune response is triggered in intestinal cells by digestion of gluten proteins. Ingestion of proteins found in wheat, barley and rye, causes villous atrophy in the small intestine. Lifelong dietary avoidance of these foodstuffs in a gluten-free diet is the only treatment.

- Enterovirusesare named by their transmission-route through the intestine (entericmeaning intestinal), but their symptoms are not mainly associated with the intestine.

- Endometriosiscan affect the intestines, with similar symptoms to IBS.

- Bowel twist(or similarly, bowel strangulation) is a comparatively rare event (usually developing sometime after major bowel surgery). It is, however, hard to diagnose correctly, and if left uncorrected can lead to bowelinfarctionand death. (The singerMaurice Gibbis understood to have died from this.)

- Angiodysplasiaof the colon

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Hirschsprung's disease(aganglionosis)

- Intussusception

- Polyp (medicine)(see alsocolorectal polyp)

- Pseudomembranous colitis

- Toxic megacolonusually a complication of ulcerative colitis

Uses of animal guts

[edit]Intestines from animals other than humans are used in a number of ways. From each species oflivestockthat is a source ofmilk,a correspondingrennetis obtained from the intestines of milk-fedcalves.Pigandcalfintestines are eaten, and pig intestines are used assausagecasings. Calf intestines supplycalf-intestinal alkaline phosphatase(CIP), and are used to makegoldbeater's skin. Other uses are:

- The use of animal gutstringsby musicians can be traced back to thethird dynasty of Egypt.In the recent past, strings were made out oflambgut. With the advent of the modern era, musicians have tended to use strings made ofsilk,or synthetic materials such asnylonorsteel.Some instrumentalists, however, still use gut strings in order to evoke the older tone quality. Although such strings were commonly referred to as "catgut"strings,catswere never used as a source for gut strings.[53]

- Sheep gut was the original source for natural gut string used inracquets,such as fortennis.Today, synthetic strings are much more common, but the best gut strings are now made out ofcowgut.

- Gut cord has also been used to produce strings for the snares that provide asnare drum's characteristic buzzing timbre. While the modern snare drum almost always uses metal wire rather than gut cord, theNorth Africanbendirframe drum still uses gut for this purpose.

- "Natural"sausagehulls, orcasings,are made of animal gut, especially hog, beef, and lamb.

- The wrapping ofkokoretsi,gardoubakia,andtorcinellois made of lamb (or goat) gut.

- Haggisis traditionally boiled in, and served in, a sheep stomach.

- Chitterlings,a kind of food, consist of thoroughly washedpig's gut.

- Animal gut was used to make the cord lines inlongcase clocksand forfuseemovements inbracket clocks,but may be replaced by metal wire.

- The oldest knowncondoms,from 1640 AD, were made from animal intestine.[54]

See also

[edit]- Gastrointestinal physiology

- Gut-on-a-chip

- All pages with titles beginning withGastrointestinal

- All pages with titles containingGastrointestinal

References

[edit]- ^"Overview of Invertebrates".www.ck12.org.6 October 2015.Retrieved25 June2021.

- ^Ruppert EE, Fox RS, Barnes RD (2004). "Introduction to Bilateria".Invertebrate Zoology(7 ed.). Brooks / Cole. p. 197[1].ISBN978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^"gastrointestinal tract"atDorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^Gastrointestinal+tractat the U.S. National Library of MedicineMedical Subject Headings(MeSH)

- ^"digestive system"atDorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^G., Hounnou; C., Destrieux; J., Desmé; P., Bertrand; S., Velut (2002-12-01). "Anatomical study of the length of the human intestine".Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy.24(5): 290–294.doi:10.1007/s00276-002-0057-y.ISSN0930-1038.PMID12497219.S2CID33366428.

- ^Raines, Daniel; Arbour, Adrienne; Thompson, Hilary W.; Figueroa-Bodine, Jazmin; Joseph, Saju (2014-05-26). "Variation in small bowel length: Factor in achieving total enteroscopy?".Digestive Endoscopy.27(1): 67–72.doi:10.1111/den.12309.ISSN0915-5635.PMID24861190.S2CID19069407.

- ^Lin, L; Zhang, J (2017)."Role of intestinal microbiota and metabolites on gut homeostasis and human diseases".BMC Immunology.18(1): 2.doi:10.1186/s12865-016-0187-3.PMC5219689.PMID28061847.

- ^Marchesi, J. R; Adams, D. H; Fava, F; Hermes, G. D; Hirschfield, G. M; Hold, G; Quraishi, M. N; Kinross, J; Smidt, H; Tuohy, K. M; Thomas, L. V; Zoetendal, E. G; Hart, A (2015)."The gut microbiota and host health: A new clinical frontier".Gut.65(2): 330–339.doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309990.PMC4752653.PMID26338727.

- ^Clarke, Gerard; Stilling, Roman M; Kennedy, Paul J; Stanton, Catherine; Cryan, John F; Dinan, Timothy G (2014)."Minireview: Gut Microbiota: The Neglected Endocrine Organ".Molecular Endocrinology.28(8): 1221–38.doi:10.1210/me.2014-1108.PMC5414803.PMID24892638.

- ^Nelson RJ. 2005. Introduction toBehavioral Endocrinology.Sinauer Associates: Massachusetts. p 57.

- ^Thomasino, Anne Marie (2001)."Length of a Human Intestine".The Physics Factbook.

- ^Upper+Gastrointestinal+Tractat the U.S. National Library of MedicineMedical Subject Headings(MeSH)

- ^David A. Warrell (2005).Oxford textbook of medicine: Sections 18-33.Oxford University Press. pp. 511–.ISBN978-0-19-856978-7.Retrieved1 July2010.

- ^Lower+Gastrointestinal+Tractat the U.S. National Library of MedicineMedical Subject Headings(MeSH)

- ^Kapoor, Vinay Kumar (13 Jul 2011). Gest, Thomas R. (ed.)."Large Intestine Anatomy".Medscape.WebMD LLC.Retrieved2013-08-20.

- ^Gray, Henry(1918).Gray's Anatomy.Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

- ^abDrake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2015).Gray's anatomy for students(3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. p. 312.ISBN978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ^abcHelander, Herbert F.; Fändriks, Lars (2014-06-01). "Surface area of the digestive tract - revisited".Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology.49(6): 681–689.doi:10.3109/00365521.2014.898326.ISSN1502-7708.PMID24694282.S2CID11094705.

- ^Hall, John (2011).Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology(Twelfth ed.). Saunders/Elsevier. p. 794.ISBN9781416045748.

- ^Bruce M. Carlson (2004).Human Embryology and Developmental Biology(3rd ed.). Saint Louis: Mosby.ISBN978-0-323-03649-8.

- ^Abraham L. Kierszenbaum (2002).Histology and cell biology: an introduction to pathology.St. Louis: Mosby.ISBN978-0-323-01639-1.

- ^abcSarna, S.K. (2010). "Introduction".Colonic Motility: From Bench Side to Bedside.San Rafael, California: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences.ISBN9781615041503.

- ^"The human proteome in gastrointestinal tract - The Human Protein Atlas".www.proteinatlas.org.Retrieved2017-09-21.

- ^Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (2015-01-23). "Tissue-based map of the human proteome".Science.347(6220): 1260419.doi:10.1126/science.1260419.ISSN0036-8075.PMID25613900.S2CID802377.

- ^Gremel, Gabriela; Wanders, Alkwin; Cedernaes, Jonathan; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn; Edlund, Karolina; Sjöstedt, Evelina; Uhlén, Mathias; Pontén, Fredrik (2015-01-01). "The human gastrointestinal tract-specific transcriptome and proteome as defined by RNA sequencing and antibody-based profiling".Journal of Gastroenterology.50(1): 46–57.doi:10.1007/s00535-014-0958-7.ISSN0944-1174.PMID24789573.S2CID21302849.

- ^Degen, L.P.; Phillips, S.F. (August 1996), "Variability of gastrointestinal transit in healthy women and men",Gut,39(2): 299–305,doi:10.1136/gut.39.2.299,PMC1383315,PMID8977347

- ^Madsen, MD, Jan Lysgard (1992), "Effects of gender, age, and body mass index on gastrointestinal transit times",Digestive Diseases and Sciences,37(10): 1548–1553,doi:10.1007/BF01296501,PMID1396002

- ^abBowen, Richard."Gastrointestinal Transit: How Long Does It Take?".Colorado State University.

- ^Keendjele, Tuwilika P. T.; Eelu, Hilja H.; Nashihanga, Tunelago E.; Rennie, Timothy W.; Hunter, Christian John (1 March 2021)."Corn? When did I eat corn? Gastrointestinal transit time in health science students".Advances in Physiology Education.45(1): 103–108.doi:10.1152/advan.00192.2020.PMID33544037.S2CID231817664.

- ^Wilson, Malcom J.; Dickson, W.H.; Singleton, A.C. (1929), "Rate of evacuation of various foods from the normal stomach: a preliminary communication",Arch Intern Med,44:787–796,doi:10.1001/archinte.1929.00140060002001

- ^Kim, SK (1968)."Small intestine transit time in the normal small bowel study".American Journal of Roentgenology.104(3): 522–524.doi:10.2214/ajr.104.3.522.PMID5687899.

- ^Ghoshal, U. C.; Sengar, V.; Srivastava, D. (2012)."Colonic Transit Study Technique and Interpretation: Can These be Uniform Globally in Different Populations with Non-uniform Colon Transit Time?".Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility.18(2): 227–228.doi:10.5056/jnm.2012.18.2.227.PMC3325313.PMID22523737.

- ^Mowat, Allan M.; Agace, William W. (2014-10-01). "Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system".Nature Reviews. Immunology.14(10): 667–685.doi:10.1038/nri3738.ISSN1474-1741.PMID25234148.S2CID31460146.

- ^Flannigan, Kyle L.; Geem, Duke; Harusato, Akihito; Denning, Timothy L. (2015-07-01)."Intestinal Antigen-Presenting Cells: Key Regulators of Immune Homeostasis and Inflammation".The American Journal of Pathology.185(7): 1809–1819.doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.02.024.ISSN1525-2191.PMC4483458.PMID25976247.

- ^Sánchez de Medina, Fermín; Romero-Calvo, Isabel; Mascaraque, Cristina; Martínez-Augustin, Olga (2014-12-01)."Intestinal inflammation and mucosal barrier function".Inflammatory Bowel Diseases.20(12): 2394–2404.doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000204.ISSN1536-4844.PMID25222662.S2CID11434730.

- ^Schubert, Mitchell L. (2014-11-01). "Gastric secretion".Current Opinion in Gastroenterology.30(6): 578–582.doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000125.ISSN1531-7056.PMID25211241.S2CID8267813.

- ^Márquez, Mercedes; Fernández Gutiérrez Del Álamo, Clotilde; Girón-González, José Antonio (2016-01-28)."Gut epithelial barrier dysfunction in human immunodeficiency virus-hepatitis C virus coinfected patients: Influence on innate and acquired immunity".World Journal of Gastroenterology.22(4): 1433–1448.doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i4.1433.ISSN2219-2840.PMC4721978.PMID26819512.

- ^Furusawa, Yukihiro; Obata, Yuuki; Fukuda, Shinji; Endo, Takaho A.; Nakato, Gaku; Takahashi, Daisuke; Nakanishi, Yumiko; Uetake, Chikako; Kato, Keiko; Kato, Tamotsu; Takahashi, Masumi; Fukuda, Noriko N.; Murakami, Shinnosuke; Miyauchi, Eiji; Hino, Shingo; Atarashi, Koji; Onawa, Satoshi; Fujimura, Yumiko; Lockett, Trevor; Clarke, Julie M.; Topping, David L.; Tomita, Masaru; Hori, Shohei; Ohara, Osamu; Morita, Tatsuya; Koseki, Haruhiko; Kikuchi, Jun; Honda, Kenya; Hase, Koji; Ohno, Hiroshi (2013). "Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells".Nature.504(7480): 446–450.Bibcode:2013Natur.504..446F.doi:10.1038/nature12721.PMID24226770.S2CID4408815.

- ^Knight, Judson (2002).Science of Everyday Things: Real-life biology.Vol. 4. Gale.ISBN9780787656348.

- ^Azzouz, Laura L.; Sharma, Sandeep (31 July 2023)."Physiology, Large Intestine".National Library of Medicine.StatPearls Publishing.PMID29939634.Retrieved24 March2024.

- ^Jakoby, WB; Ziegler, DM (5 December 1990)."The enzymes of detoxication".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.265(34): 20715–8.doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)45272-0.PMID2249981.

- ^Joel, Lucas (10 January 2020)."Fossil Reveals Earth's Oldest Known Animal Guts - The find in a Nevada desert revealed an intestine inside a creature that looks like a worm made of a stack of ice cream cones".The New York Times.Retrieved10 January2020.

- ^Svhiffbauer, James D.; et al. (10 January 2020)."Discovery of bilaterian-type through-guts in cloudinomorphs from the terminal Ediacaran Period".Nature Communications.11(205): 205.Bibcode:2020NatCo..11..205S.doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13882-z.PMC6954273.PMID31924764.

- ^Nielsen, C., Brunet, T. & Arendt, D. Evolution of the bilaterian mouth and anus. Nat Ecol Evol 2, 1358–1376 (2018).https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0641-0

- ^De Robertis, E. M., & Tejeda-Muñoz, N. (2022). Evo-Devo of urbilateria and its larval forms.Developmental Biology,487,10–20.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2022.04.003

- ^Nitzan, Orna; Elias, Mazen; Peretz, Avi; Saliba, Walid (2016-01-21)."Role of antibiotics for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease".World Journal of Gastroenterology.22(3): 1078–1087.doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i3.1078.ISSN1007-9327.PMC4716021.PMID26811648.

- ^Wier LM, Steiner CA, Owens PL (February 2015)."Surgeries in Hospital-Owned Outpatient Facilities, 2012".HCUP Statistical Brief(188). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- ^Fox, James; Timothy Wang (January 2007)."Inflammation, Atrophy, and Gastric Cancer".Journal of Clinical Investigation.review.117(1): 60–69.doi:10.1172/JCI30111.PMC1716216.PMID17200707.

- ^Murphy, Kenneth (20 May 2014).Janeway's Immunobiology.New York: Garland Science, Taylor and Francis Group, LLC. pp. 389–398.ISBN978-0-8153-4243-4.

- ^Parham, Peter (20 May 2014).The Immune System.New York: Garland Science Taylor and Francis Group LLC. p. 494.ISBN978-0-8153-4146-8.

- ^Goering, Richard (20 May 2014).MIMS Medical Microbiology.Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 32, 64, 294, 133–4, 208, 303–4, 502.ISBN978-0-3230-4475-2.

- ^Hiskey, Daven (12 November 2010)."Violin strings were never made out of actual cat guts".TodayIFoundOut.com.Retrieved15 December2015.

- ^"World's oldest condom".Ananova.2008.Retrieved2008-04-11.