Hulegu Khan

Hulegu Khan

| |

|---|---|

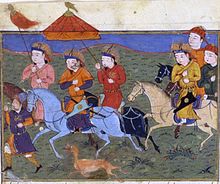

Painting of Hulegu Khan onRashid-al-Din Hamadani,early 14th century. | |

| Ilkhan | |

| Reign | 1256 – 8 February 1265 |

| Successor | Abaqa Khan |

| Born | c. 1217 Mongolia |

| Died | (aged 47) Zarrineh River |

| Burial | |

| Consort |

|

| Issue | See below |

| House | Borjigin |

| Father | Tolui |

| Mother | Sorghaghtani Beki |

| Religion | Buddhism[1][2] |

| Tamgha |  |

Hulegu Khan,also known asHülegüorHulagu[n 1](c. 1217 –8 February 1265), was aMongolruler who conquered much ofWestern Asia.Son ofToluiand theKeraiteprincessSorghaghtani Beki,he was a grandson ofGenghis Khanand brother ofAriq Böke,Möngke Khan,andKublai Khan.

Hulegu's army greatly expanded the southwestern portion of theMongol Empire,founding theIlkhanateinPersia.Under Hulegu's leadership, theMongols sacked and destroyed Baghdadending theIslamic Golden Ageand weakenedDamascus,causing a shift of Islamic influence to theMamluk SultanateinCairoand ended theAbbasid Dynasty.

Background

[edit]Hulegu was born toTolui,one of Genghis Khan's sons, andSorghaghtani Beki,an influentialKeraiteprincess and a niece ofToghrulin 1217.[3]Nothing much is known of Hulegu's childhood except of an anecdote given inJami' al-Tawarikhand he once met his grandfatherGenghis KhanwithKublaiin 1224.

Military campaigns

[edit]

Hulegu's brotherMöngke Khanhad been installed as Great Khan in 1251.Möngkecharged Hulegu with leading a massive Mongol army to conquer or destroy the remaining Muslim states in southwestern Asia. Hulegu's campaign sought the subjugation of theLursof southern Iran,[3]thedestruction of the Nizari Ismaili state (the Assassins),the submission or destruction of theAbbasid CaliphateinBaghdad,the submission or destruction of theAyyubid statesinSyriabased inDamascus,and finally, the submission or destruction of theBahriMamluke Sultanateof Egypt.[4]Möngke ordered Hulegu to treat kindly those who submitted and utterly destroy those who did not. Hulegu vigorously carried out the latter part of these instructions.

Hulegu marched out with perhaps the largest Mongol army ever assembled – by order of Möngke, two-tenths of the empire's fighting men were gathered for Hulegu'sarmy[5]in 1253. He arrived atTransoxianain 1255. He easily destroyed the Lurs, and the Assassins surrendered their impregnable fortress ofAlamutwithout a fight, accepting a deal that spared the lives of their people in early 1256. He choseAzerbaijanas his power base, while orderingBaijuto retreat to Anatolia. From at least 1257 onwards,MuslimsandChristiansof every major religious variety inEurope,theMiddle East,andmainlandAsiawere a part of Hulegu's army.[6]

Siege of Baghdad

[edit]Hulegu's Mongol army set out for Baghdad in November 1257. Once near the city he divided his forces to threaten the city on both the east and west banks of the Tigris. Hulegu demanded surrender, but the caliph,Al-Musta'sim,refused. Due to the treason of Abu Alquma, an advisor to Al-Muta'sim, an uprising in the Baghdad army took place and Siege of Baghdad began. The attacking Mongols broke dikes and flooded the ground behind the caliph's army, trapping them. Much of the army was slaughtered or drowned.

The Mongols under Chinese generalGuo Kanlaid siege to the city on 29 January 1258,[7]constructing a palisade and a ditch and wheeling up siege engines andcatapults.The battle was short by siege standards. By 5 February the Mongols controlled a stretch of the wall. The caliph tried to negotiate but was refused. On 10 February Baghdad surrendered. The Mongols swept into the city on 13 February and began a week of destruction. TheGrand Library of Baghdad,containing countless precious historical documents and books on subjects ranging from medicine toastronomy,was destroyed. Citizens attempted to flee but were intercepted by Mongol soldiers.

Death counts vary widely and cannot be easily substantiated: A low estimate is about 90,000 dead;[8]higher estimates range from 200,000 to a million.[9]The Mongols looted and then destroyed. Mosques, palaces, libraries, hospitals—grand buildings that had been the work of generations—were burned to the ground. The caliph was captured and forced to watch as his citizens were murdered and his treasury plundered.Il Milione,a book on the travels ofVenetianmerchantMarco Polo,states that Hulegu starved the caliph to death, but there is no corroborating evidence for that. Most historians believe the Mongol and Muslim accounts that the caliph was rolled up in a rug and the Mongols rode their horses over him, as they believed that the earth would be offended if touched by royal blood. All but one of his sons were killed. Baghdad was a depopulated, ruined city for several centuries. Smaller states in the region hastened to reassure Hulegu of their loyalty, and the Mongols turned toSyriain 1259, conquering the Ayyubid dynasty and sending advance patrols as far ahead asGaza.

A thousand squads of northern Chinesesappersaccompanied the Hulegu during his conquest of the Middle East.[10]

Conquest of Syria (1260)

[edit]

In 1260 Mongol forces combined with those of their Christian vassals in the region, including the army of theArmenian Kingdom of CiliciaunderHethum I, King of Armeniaand the Franks ofBohemond VI of Antioch.This force conquered Muslim Syria, a domain of the Ayyubid dynasty. Theycaptured Aleppo by siegeand, under the Christian generalKitbuqa,seizedDamascuson 1 March 1260.[a]A Christian Mass was celebrated in theUmayyad Mosqueand numerous mosques were profaned. Many historical accounts describe the three Christian rulers Hethum, Bohemond, andKitbuqaentering the city of Damascus together in triumph,[13][14]though some modern historians such asDavid Morganhave questioned this story asapocryphal.[15]

The invasion effectively destroyed the Ayyubids, which was until then a powerful dynasty that had ruled large parts of theLevant,Egypt,and theArabian Peninsula.The last Ayyubid king,An-Nasir Yusuf,had been killed by Hulegu this same year.[16]With Baghdad ravaged and Damascus weakened, the center of Islamic power shifted to the Mamluk sultan's capital of Cairo.

Hulegu intended to send forces southward throughPalestinetoward Cairo. So he had a threatening letter delivered by an envoy to the MamlukSultan Qutuzin Cairo demanding that Qutuz open his city or it would be destroyed like Baghdad. Then, because food and fodder in Syria had become insufficient to supply his full force, and because it was a regular Mongol practice to move troops to the cooler highlands for the summer,[17]Hulegu withdrew his main force to Iran near Azerbaijan, leaving behind one tumen (10,000 men or less) underKitbuqa,accompanied by Armenian, Georgian, and Frankish volunteers, which Hulegu considered sufficient. Hulegu then personally departed for Mongolia to play his role in the imperial succession conflict occasioned by the death some eight months earlier ofGreat Khan Möngke.But upon receiving news of how few Mongols now remained in the region,Qutuzquickly assembled his well-trained and equipped 20,000-strong army at Cairo and invaded Palestine.[18][unreliable source?]He then allied himself with a fellow Mamluk leader,Baybarsin Syria, who not only needed to protect his own future from the Mongols but was eager to avenge for Islam the Mongol capture of Damascus, looting of Baghdad, and conquest of Syria.

The Mongols, for their part, attempted to form a Frankish-Mongol alliance with (or at least, demand the submission of) the remnant of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, now centered on Acre, butPope Alexander IVhad forbidden such an alliance. Tensions between Franks and Mongols also increased whenJulian of Sidoncaused an incident resulting in the death of one of Kitbuqa's grandsons. Angered,Kitbuqahad sacked Sidon. The Barons of Acre, contacted by the Mongols, had also been approached by the Mamluks, seeking military assistance against the Mongols. Although the Mamluks were traditional enemies of the Franks, the Barons of Acre recognized the Mongols as the more immediate menace. Instead of taking sides, the Crusaders opted for a position of cautious neutrality between the two forces. In an unusual move, however, they allowed the Egyptian Mamluks to march northward without hindrance through Crusader territory and even let them camp near Acre to resupply.

Battle of Ain Jalut

[edit]

When news arrived that the Mongols had crossed theJordan Riverin 1260,Sultan Qutuzand his forces proceeded southeast toward the 'Spring of Goliath' (Known in Arabic as 'Ain Jalut') in theJezreel Valley.They met the Mongol army of about 12,000 in theBattle of Ain Jalutand fought relentlessly for many hours. The Mamluk leader Baybars mostly implementedhit-and-run tacticsin an attempt to lure the Mongol forces into chasing him. Baybars andQutuzhad hidden the bulk of their forces in the hills to wait in ambush for the Mongols to come into range. The Mongol leaderKitbuqa,already provoked by the constant fleeing of Baybars and his troops, decided to march forwards with all his troops on the trail of the fleeing Egyptians. When the Mongols reached the highlands, Egyptians appeared from hiding, and the Mongols found themselves surrounded by enemy forces as the hidden troops hit them from the sides andQutuzattacked the Mongol rear. Estimates of the size of the Egyptian army range from 24,000 to 120,000. The Mongols broke free of the trap and even mounted a temporarily successful counterattack, but their numbers had been depleted to the point that the outcome was inevitable. Refusing to surrender, the whole Mongol army that had remained in the region, includingKitbuqa,were cut down and killed that day. The battle of Ain Jalut established a high-water mark for the Mongol conquest.

Civil War

[edit]

After the succession was settled and his brotherKublai Khanwas established as Great Khan, Hulegu returned to his lands by 1262. When he massed his armies to attack the Mamluks and avenge the defeat at Ain Jalut, however, he was instead drawn into civil war withBatu Khan's brotherBerke.Berke Khan, a Muslim convert and the grandson of Genghis Khan, had promised retribution in his rage after Hulegu's sack of Baghdad and allied himself with the Mamluks. He initiated a large series of raids on Hulegu's territories, led byNogai Khan.Hulegu suffered a severe defeat in an attempted invasion north of theCaucasusin 1263. This was the first open war between Mongols and signaled the end of the unified empire. In retaliation for his failure, Hulegu killed Berke'sortogh,and Berke did the same in return.[19]

Even while Berke was Muslim, out of Mongol brotherhood he at first resisted the idea of fighting Hulegu. He said, "Mongols are killed by Mongol swords. If we were united, then we would have conquered all of the world." But the economic situation of the Golden Horde due to the actions of the Ilkhanate led him to declare jihad because the Ilkhanids were hogging the wealth of North Iran and because of the Ilkhanate's demands for the Golden Horde not to sell slaves to the Mamluks.[20]

Communications with Europe

[edit]Hulegu's mother Sorghaghtani successfully navigated Mongol politics, arranging for all of her sons to become Mongol leaders. She was aChristianof theChurch of the East(often referred to as "Nestorianism" ) and Hulegu was friendly toChristianity.Hulegu's favorite wife,Doquz Khatun,was also a Christian, as was his closest friend and general,Kitbuqa.Hulegu sent multiple communications to Europe in an attempt to establish aFranco-Mongol allianceagainst the Muslims. In 1262, he sent his secretaryRychaldusand an embassy to "all kings and princes overseas". The embassy was apparently intercepted in Sicily byManfred, King of Sicily,who was allied with theMamluk Sultanateand in conflict withPope Urban IV,and Rychaldus was returned by ship.[21]

On 10 April 1262, Hulegu sent a letter, throughJohn the Hungarian,toLouis IX of France,offering an alliance.[22]It is unclear whether the letter ever reached Louis IX in Paris – the only manuscript known to have survived was inVienna,Austria.[23]The letter stated Hulegu's intention to capture Jerusalem for the benefit of the Pope and asked for Louis to send a fleet against Egypt:

From the head of the Mongol army, anxious to devastate the perfidious nation of the Saracens, with the good-will support of the Christian faith (...) so that you, who are the rulers of the coasts on the other side of the sea, endeavor to deny a refuge for the Infidels, your enemies and ours, by having your subjects diligently patrol the seas.

— Letter from Hulegu to Saint Louis.[24]

Despite many attempts, neither Hulegu nor his successors were able to form an alliance with Europe, although Mongol culture in the West was in vogue in the 13th century. Many new-born children in Italy were named after Mongol rulers, including Hulegu: names such as Can Grande ( "Great Khan" ), Alaone (Hulegu), Argone (Arghun), and Cassano (Ghazan) are recorded.[25]

Family

[edit]Hulegu had fourteen wives and concubines with at least 21 issues with them:

Principal wives:

- Guyuk Khatun (died inMongoliabefore reaching Iran) – daughter of Toralchi Güregen of theOirattribe andChecheikhenKhatun

- Qutui Khatun– daughter of Chigu Noyan ofKhongiradtribe and Tümelün behi (daughter ofGenghis khanandBörte)

- Takshin (d. 12 September 1270 ofurinary incontinence)

- Tekuder(1246–1284)

- Todogaj Khatun[26]– married to Tengiz Güregen, married secondly to Sulamish his son, married thirdly to Chichak, son of Sulamish

- Yesunchin Khatun (d. January/February 1272) – a lady from theSuldustribe

- Abaqa(1234–1282)

- Dokuz Khatun,daughter of Uyku (son ofToghrul) and widow ofTolui

- Öljei Khatun – half-sister of Guyuk, daughter of Toralchi Güregen of theOirattribe

- Möngke Temür(b. 23 October 1256, d. 26 April 1282)

- Jamai Khatun – married Jorma Güregen after her sister Bulughan's death

- Manggugan Khatun – married firstly to her cousin Chakar Güregen (son of Buqa Timur and niece of Öljei Khatun), married secondly to his son Taraghai

- Baba Khatun – married to Lagzi Güregen, son ofArghun Aqa

Concubines:

- Nogachin Aghchi, a lady fromCathay;from camp ofQutui Khatun

- Tuqtani (or Toqiyatai) Egechi (d. 20 February 1292) – sister ofIrinjin,niece of Dokuz Khatun

- Boraqchin Agachi, from camp of Qutui Khatun

- Taraghai (died bylightning strikeon his way to Iran in 1260s)

- Arighan Agachi (d. 8 February 1265) – daughter of Tengiz Güregen; from camp of Qutui Khatun

- Ajuja Agachi, a lady fromChinaorKhitans,from camp of Dokuz Khatun

- Yeshichin Agachi, a lady from the Kür'lüüt tribe; from camp of Qutui Khatun

- Yesüder – Viceroy ofKhorasanduring Abaqa's reign

- A daughter (married to Esen Buqa Güregen, son of Noqai Yarghuchi)

- Khabash – posthumous son

- Yesüder – Viceroy ofKhorasanduring Abaqa's reign

- El Agachi – a lady from theKhongiradtribe; from camp of Dokuz Khatun

- Irqan Agachi (Tribe unknown)

- Taraghai Khatun – married to Taghai Timur (renamed Musa) ofKhongirad(son of Shigu Güregen) and Temülun Khatun (daughter ofGenghis Khan)

- Mangligach Agachi (Tribe unknown)

- Qutluqqan Khatun – married firstly to Yesu Buqa Güregen, son of Urughtu Noyan of theDörbentribe, married secondly Tukel, son of Yesu Buqa

- A concubine from Qutui Khatun's camp:

- Toqai Timur (d. 1289)[27]

- Qurumushi

- Hajji

- Toqai Timur (d. 1289)[27]

Death

[edit]Hulegu Khan fell seriously ill in January 1265 and died the following month on the banks ofZarrineh River(then called Jaghatu) and was buried onShahi IslandinLake Urmia.His funeral was the only Ilkhanate funeral to featurehuman sacrifice.[28]His tomb has never been found.[29]

Legacy

[edit]Hulegu Khan laid the foundations of theIlkhanateand thus paved the way for the laterSafavid dynasticstate, and ultimately the modern country ofIran.Hulegu's conquests also opened Iran to both European influence from the west and buddhist influence from the east. Thus, combined with patronage from his successors, would develop Iran's distinctive excellence in architecture. Under Hulegu's dynasty, Iranian historians began writing in Persian rather than Arabic.[30]It is recorded however that he converted toBuddhismas he neared death,[31]against the will ofDoquz Khatun.[32]The erection of a Buddhist temple atḴoytestifies his interest in that religion.[3]Recent translations of various Tibetan monks' letters and epistles to Hulegu confirms that he was a lifelong Buddhist, following theKagyu school.[33]

Hulegu also patronizedNasir al-Din Tusiand his researches inMaragheh observatory.Another of his proteges were Juvayni brothersAta MalikandShams al-Din Juvayni.His reign as the ruler of Ilkhanate was peaceful and tolerant to diversity.[34]

In popular media

[edit]- Portrayed byKurt KatchinAli Baba and the Forty Thieves(1944)

- Portrayed byPranin the 1956 Indian filmHalaku.

- Portrayed byÖztürk SerengilinCengiz Han'ın Hazineleri(1962)[35]

- Portrayed by Zhang Jingda and Zhang Bolun inThe Legend of Kublai Khan(2013)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Grousset, René (1970).The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia.Rutgers University Press. p.358.ISBN9780813513041.

- ^Vaziri, Mostafa (2012). "Buddhism during the Mongol Period in Iran".Buddhism in Iran: An Anthropological Approach to Traces and Influences.Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 111–131.doi:10.1057/9781137022943_7.ISBN9781137022943.

- ^abc"Hulāgu Khan"atEncyclopædia Iranica

- ^Amitai-Preiss, Reuven.The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War

- ^John Joseph Saunders,The History of the Mongol Conquests,1971.

- ^Chua, Amy (2007).Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance–and Why They Fall(1st ed.). New York:Doubleday.p. 111.ISBN978-0-385-51284-8.OCLC123079516.

- ^"Six Essays from the Book of Commentaries on Euclid".World Digital Library.Retrieved21 March2013.

- ^Sicker 2000, p. 111.

- ^New Yorker, April 25, 2005, Ian Frazier, "Invaders - Destroying Baghdad"

- ^Josef W. Meri (2005). Josef W. Meri (ed.).Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia.Psychology Press. p. 510.ISBN0-415-96690-6.Retrieved28 November2011.

This called for the employment of engineers to engage in mining operations, to build siege engines and artillery, and to concoct and use incendiary and explosive devices. For instance, Hulagu, who led Mongol forces into the Middle East during the second wave of the invasions in 1250, had with him a thousand squads of engineers, evidently of north Chinese (or perhaps Khitan) provenance.

- ^"In May 1260, a Syrian painter gave a new twist to the iconography of the Exaltation of the Cross by showing Constantine and Helena with the features of Hulegu and his Christian wife Doquz Khatun" inCambridge History of ChristianityVol. 5 Michael Angold p. 387Cambridge University PressISBN0-521-81113-9

- ^Le Monde de la BibleN. 184 July–August 2008, p. 43

- ^abRunciman 1987,p. 307.

- ^Grousset, p. 588

- ^Jackson 2014.

- ^Atlas des Croisades, p. 108

- ^Pow, Lindsey Stephen (2012).Deep Ditches and Well-Built Walls: a Reappraisal of the Mongol Withdrawal from Europe in 1242(Master's thesis). University of Calgary. p. 32.OCLC879481083.

- ^Corbyn, James (2015).In What Sense Can Ayn Jalut be Viewed as a Decisive Engagement?(Master's thesis). Royal Holloway University of London. pp. 7–9.

- ^Enkhbold, Enerelt (2019). "The role of the ortoq in the Mongol Empire in forming business partnerships".Central Asian Survey.38(4): 531–547.doi:10.1080/02634937.2019.1652799.S2CID203044817.

- ^Johan Elverskog (2011).Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road.University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 186–.ISBN978-0-8122-0531-2.

- ^Jackson 2014,p. 173.

- ^Jackson 2014,p. 178.

- ^Jackson 2014,p. 166.

- ^Letter from Hulegu to Saint Louis, quoted inLes Croisades,Thierry Delcourt, p. 151

- ^Jackson 2014,p. 315.

- ^Landa, Ishayahu (2018)."Oirats in the Ilkhanate and the Mamluk Sultanate in the Thirteenth to the Early Fifteenth Centuries: Two Cases of Assimilation into the Muslim Environment (MSR XIX, 2016)"(PDF).Mamlūk Studies Review.doi:10.6082/M1B27SG2.

- ^abcBrack, Jonathan Z. (2016).Mediating Sacred Kingship: Conversion and Sovereignty in Mongol Iran(Thesis).hdl:2027.42/133445.

- ^Morgan, p. 139

- ^Henry Filmer (1937).The Pageant Of Persia.p. 224.

- ^Francis Robinson,The Mughal Emperors And The Islamic Dynasties of India, Iran and Central Asia,pp. 19 & 36

- ^Hildinger 1997,p. 148.

- ^Jackson 2014,p. 176.

- ^Martin, Dan; Samten, Jampa (2014)."Letters for the Khans: Six Tibetan Epistles for the Mongol Rulers Hulegu and Khubilai, and the Tibetan Lama Pagpa. Co-authored with Jampa Samten".In Roberto Vitali (ed.).Trails of The Tibetan Tradition: Papers for Elliot Sperling.Amnye Machen Institute.ISBN9788186227725.

- ^Nehru, Jawaharlal.Glimpses of World History.Penguin Random House.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^Yilmaz, Atif (10 October 1962),Cengiz Han'in hazineleri(Adventure, Comedy), Orhan Günsiray, Fatma Girik, Tülay Akatlar, Öztürk Serengil, Yerli Film,retrieved1 February2021

Works cited

[edit]- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004).The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire.Facts on File, Inc.ISBN0-8160-4671-9.

- Boyle, J.A., (Editor).The Cambridge History of Iran: Volume 5, The Saljuq and Mongol Periods.Cambridge University Press; Reissue ed., (1968).ISBN0-521-06936-X.

- Hildinger, Erik(1997).Warriors of the Steppe: A Military History of Central Asia, 500 B.C. to 1700 A.D.Da Capo Press.ISBN0-306-81065-4.

- Morgan, David.The Mongols.Blackwell Publishers; Reprint ed., 1990.ISBN0-631-17563-6.Best for an overview of the wider context of medieval Mongol history and culture.

- Runciman, Steven (1987).A History of the Crusades: Volume 3, The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521347723.

- Jackson, Peter(2014).The Mongols and the West: 1221–1410.Taylor & Francis.ISBN978-1-317-87898-8.

- Robinson, Francis.The Mughal Emperors And the Islamic Dynasties of India, Iran and Central Asia.Thames and Hudson Limited; 2007.ISBN0-500-25134-7

External links

[edit]- A long articleabout Hulegu's conquest ofBaghdad,written byIan Frazier,appeared in the 25 April 2005 issue ofThe New Yorker.

- An Osama bin Laden tapein whichOsama bin Ladencompares Vice PresidentDick Cheneyand Secretary of StateColin Powellto Hulegu and his attack onBaghdad.Dated 12 November 2002.

- Hulegu the Mongol,by Nicolas Kinloch, published in History Today, Volume 67 Issue 6 June 2017.