Bosnian language

| Bosnian | |

|---|---|

| Bosniak | |

| bosanski/босански | |

| Pronunciation | [bɔ̌sanskiː] |

| Native to | Bosnia and Herzegovina(Bosnia),Sandžak(SerbiaandMontenegro) andKosovo |

| Ethnicity | Bosniaks |

Native speakers | 2.7 million (2020)[1] |

| Latin(Gaj's Latin alphabet) Cyrillic(Serbian Cyrillic alphabet)[a] Yugoslav Braille Formerly: Arabic(Arebica) Bosnian Cyrillic(Bosančica) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | bs |

| ISO 639-2 | bos |

| ISO 639-3 | bos |

| Glottolog | bosn1245 |

| Linguasphere | part of53-AAA-g |

Countries where Bosnian is a co-official language (dark green) or a recognised minority language (light green) | |

Bosnian is not endangered according to the classification system of theUNESCOAtlas of the World's Languages in Danger[4] | |

| South Slavic languagesand dialects |

|---|

Bosnian(/ˈbɒzniən/;bosanski/босански;[bɔ̌sanskiː]), sometimes referred to asBosniak language,is thestandardizedvarietyof theSerbo-Croatianpluricentric languagemainly used by ethnicBosniaks.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11]Bosnian is one of three such varieties considered official languages ofBosnia and Herzegovina,[12]along withCroatianandSerbian.It is also an officially recognized minority language inCroatia,Serbia,[13]Montenegro,[14]North MacedoniaandKosovo.[15]

Bosnian uses both theLatinandCyrillic alphabets,[a]with Latin in everyday use.[16]It is notable among thevarietiesof Serbo-Croatian for a number ofArabic,PersianandOttoman Turkishloanwords,[b]largely due to the language's interaction with those cultures throughIslamicties.[17][18][19]

Bosnian is based on the most widespread dialect of Serbo-Croatian,Shtokavian,more specifically onEastern Herzegovinian,which is also the basis of standard Croatian, Serbian andMontenegrinvarieties. Therefore, theDeclaration on the Common Languageof Croats, Serbs, Bosniaks and Montenegrins was issued in 2017 in Sarajevo.[20][21]Although the common name for the common language remains 'Serbo-Croatian', newer alternatives such as 'Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian' and 'Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian' have been increasingly utilised since the 1990s,[22]especially within diplomatic circles.

Alphabet

[edit]Table of the modern Bosnian alphabet in both Latin and Cyrillic, as well as with the IPA value, sorted according to Cyrilic:

|

|

History

[edit]Standardization

[edit]

Although Bosnians are, at the level ofvernacular idiom,linguistically more homogeneous than either Serbians or Croatians, unlike those nations they failed tocodifya standard language in the 19th century, with at least two factors being decisive:

- The Bosnian elite, as closely intertwined with Ottoman life, wrote predominantly in foreign (Arabic, Persian, Ottoman Turkish) languages.[23]Vernacular literaturewritten in Bosnian with theArebicascript was relatively thin and sparse.

- The Bosnians' national emancipation lagged behind that of the Serbs and Croats and because denominational rather than cultural or linguistic issues played the pivotal role, a Bosnian language project did not arouse much interest or support amongst the intelligentsia of the time.

The modern Bosnian standard took shape in the 1990s and 2000s. Lexically, Islamic-Oriental loanwords are more frequent; phonetically: the phoneme /x/ (letterh) is reinstated in many words as a distinct feature ofvernacularBosniak speech and language tradition; also, there are some changes in grammar, morphology and orthography that reflect the Bosniak pre-World War Iliterary tradition, mainly that of the Bosniak renaissance at the beginning of the 20th century.

Gallery

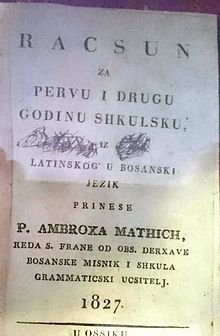

[edit]-

Nauk krstjanski za narod slovinski,byMatija Divković,the first Bosnian printed book. Published inVenice,1611

-

Bosnian dictionary byMuhamed Hevaji Uskufi Bosnevi,1631

-

TheFree Will and Acts of Faith,manuscript from the early 19th century

-

TheBosnian Book of the Science of Conductby 'Abdulvehab Žepčevi,1831

-

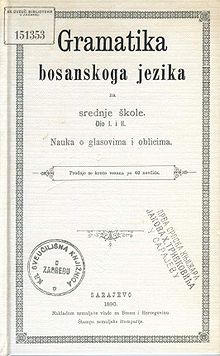

Bosnian Grammar, 1890

Controversy and recognition

[edit]

The name "Bosnian language" is a controversial issue for someCroatsandSerbs,who also refer to it as the "Bosniak" language (Serbo-Croatian:bošnjački/бошњачки,[bǒʃɲaːtʃkiː]). Bosniak linguists however insist that the only legitimate name is "Bosnian" language (bosanski) and that that is the name that both Croats and Serbs should use. The controversy arises because the name "Bosnian" may seem to imply that it is the language of all Bosnians, whileBosnian CroatsandSerbsreject that designation for their idioms.

The language is calledBosnian languagein the 1995Dayton Accords[24]and is concluded by observers to have received legitimacy and international recognition at the time.[25]

TheInternational Organization for Standardization(ISO),[26]United States Board on Geographic Names(BGN) and thePermanent Committee on Geographical Names(PCGN) recognize the Bosnian language. Furthermore, the status of the Bosnian language is also recognized by bodies such as theUnited Nations,UNESCOand translation and interpreting accreditation agencies,[27]including internet translation services.

Most English-speaking language encyclopedias (Routledge,Glottolog,[28]Ethnologue,[29]etc.)[30]register the language solely as "Bosnian" language. TheLibrary of Congressregistered the language as "Bosnian" and gave it an ISO-number. The Slavic language institutes in English-speaking countries offer courses in "Bosnian" or "Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian" language, not in "Bosniak" language (e.g. Columbia,[31]Cornell,[32]Chicago,[33]Washington,[34]Kansas).[35]The same is the case in German-speaking countries, where the language is taught under the nameBosnisch,notBosniakisch(e.g. Vienna,[36]Graz,[37]Trier)[38]with very few exceptions.

Some Croatian linguists (Zvonko Kovač,Ivo Pranjković,Josip Silić) support the name "Bosnian" language, whereas others (Radoslav Katičić,Dalibor Brozović,Tomislav Ladan) hold that the termBosnian languageis the only one appropriate[clarification needed]and that accordingly the terms Bosnian language and Bosniak language refer to two different things.[clarification needed]The Croatian state institutions, such as the Central Bureau of Statistics, use both terms: "Bosniak" language was used in the 2001 census,[39]while the census in 2011 used the term "Bosnian" language.[40]

The majority of Serbian linguists hold that the termBosniak languageis the only one appropriate,[41]which was agreed as early as 1990.[42]

The original form ofThe Constitution of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovinacalled the language "Bosniac language",[43]until 2002 when it was changed in Amendment XXIX of the Constitution of the Federation byWolfgang Petritsch.[44]The original text of the Constitution of theFederation of Bosnia and Herzegovinawas agreed inViennaand was signed byKrešimir ZubakandHaris Silajdžićon March 18, 1994.[45]

The constitution ofRepublika Srpska,the Serb-dominated entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina, did not recognize any language or ethnic group other than Serbian.[46]Bosniaks were mostly expelled from the territory controlled by the Serbs from 1992, but immediately after the war they demanded the restoration of their civil rights in those territories. The Bosnian Serbs refused to make reference to the Bosnian language in their constitution and as a result had constitutional amendments imposed byHigh RepresentativeWolfgang Petritsch.However, the constitution ofRepublika Srpskarefers to it as theLanguage spoken by Bosniaks,[47]because the Serbs were required to recognise the language officially, but wished to avoid recognition of its name.[48]

Serbia includes the Bosnian language as an elective subject in primary schools.[49]Montenegroofficially recognizes the Bosnian language: its2007 Constitutionspecifically states that althoughMontenegrinis the official language, Serbian, Bosnian, Albanian and Croatian are also in official use.[14][50]

Historical usage of the term

[edit]This section shouldspecify the languageof its non-English content, using{{lang}},{{transliteration}}for transliterated languages, and{{IPA}}for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriateISO 639 code.Wikipedia'smultilingual support templatesmay also be used.(August 2021) |

- In the workSkazanie izjavljenno o pismenehthat was written between 1423 and 1426, the Bulgarian chroniclerConstantine the Philosopher,in parallel with the Bulgarian, Serbian, Slovenian, Czech and Croatian, he also mentions the Bosnian language.[51]

- The notary book of the town of Kotor from July 3, 1436, recounts a duke buying a girl that is described as a: "Bosnian woman, heretic and in the Bosnian language called Djevena".[51][52]

- The workThesaurus Polyglottus,published inFrankfurt am Mainin 1603 by the German historian and linguistHieronymus Megiser,mentions the Bosnian dialect alongside the Dalmatian, Croatian and Serbian one.[53][54]

- The Bosnian FranciscanMatija Divković,regarded as the founder of the modern literature of Bosnia and Herzegovina,[55][56]asserts in his workNauk krstjanski za narod slovinski( "The Christian doctrine for the Slavic peoples" ) from 1611 his "translation from Latin to the real and true Bosnian language" (A privideh iz dijačkog u pravi i istinit jezik bosanski)[57]

- Bosniak poet andAljamiadowriterMuhamed Hevaji Uskufi Bosneviwho refers to the language of his 1632 dictionaryMagbuli-arifas Bosnian.[58]

- One of the first grammarians, the Jesuit clergymanBartol Kašićcalls the language used in his work from 1640Ritual rimski('Roman Rite') asnaški('our language') orbosanski('Bosnian'). He used the term "Bosnian" even though he was born in aChakavianregion: instead he decided to adopt a "common language" (lingua communis) based on a version ofShtokavianIkavian.[59][60]

- The Croatian linguistJakov Mikalja(1601–1654) who states in his dictionaryBlagu jezika slovinskoga(Thesaurus lingue Illyricae) from 1649 that he wants to include "the most beautiful words" adding that "of allIllyrianlanguages the Bosnian is the most beautiful ", and that all Illyrian writers should try to write in that language.[59][60]

- 18th century Bosniak chroniclerMula Mustafa Bašeskijawho argues in his yearbook of collected Bosnian poems that the "Bosnian language" is much richer than the Arabic, because there are 45 words for the verb "to go" in Bosnian.[57]

- The Venetian writer, naturalist and cartographerAlberto Fortis(1741–1803) calls in his workViaggio in Dalmazia( "Journey to Dalmatia" ) the language ofMorlachsas Illyrian, Morlach and Bosnian.[61]

- The Croatian writer and lexicographerMatija Petar Katančićpublished six volumes of biblical translations in 1831 described as being "transferred from Slavo-Illyrian to the pronunciation of the Bosnian language".[62]

- Croatian writerMatija Mažuranićrefers in the workPogled u Bosnu(1842) to the language of Bosnians as Illyrian (a 19th-centurysynonymtoSouth Slavic languages) mixed with Turkish words, with a further statement that they are the speakers of the Bosniak language.[63]

- The Bosnian FranciscanIvan Franjo Jukićstates in his workZemljopis i Poviestnica Bosne(1851) that Bosnia was the only Turkish land (i.e. under the control of the Ottoman Empire) that remained entirely pure without Turkish speakers, both in the villages and so on the highlands. Further he states "[...] a language other than the Bosnian is not spoken [in Bosnia], the greatest Turkish [i.e. Muslim] gentlemen only speak Turkish when they are at theVizier".[64]

- Ivan Kukuljević Sakcinski,a 19th-century Croatian writer and historian, stated in his workPutovanje po Bosni (Travels into Bosnia)from 1858, how the 'Turkish' (i.e. Muslim) Bosniaks, despite converting to the Muslim faith, preserved their traditions and the Slavic mood, and that they speak the purest variant of the Bosnian language, by refusing to add Turkish words to their vocabulary.[65]

Differences between Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian

[edit]The differences between the Bosnian, Serbian, and Croatian literary standards are minimal. Although Bosnian employs moreTurkish, Persian, and Arabic loanwords—commonly called orientalisms—mainly in its spoken variety due to the fact that most Bosnian speakers are Muslims, it is still very similar to both Serbian and Croatian in its written and spoken form.[66]"Lexical differences between the ethnic variants are extremely limited, even when compared with those between closely related Slavic languages (such as standard Czech and Slovak, Bulgarian and Macedonian), and grammatical differences are even less pronounced. More importantly, complete understanding between the ethnic variants of the standard language makes translation and second language teaching impossible."[67]

The Bosnian language, as a new normative register of the Shtokavian dialect, was officially introduced in 1996 with the publication ofPravopis bosanskog jezikain Sarajevo. According to that work, Bosnian differed from Serbian and Croatian on some main linguistic characteristics, such as: sound formats in some words, especially "h" (kahvaversus Serbiankafa); substantial and deliberate usage of Oriental ( "Turkish" ) words; spelling of future tense (kupit ću) as in Croatian but not Serbian (kupiću) (both forms have the same pronunciation).[68][better source needed]2018, in the new issue ofPravopis bosanskog jezika,words without "h" are accepted due to their prevalence in language practice.[69]

Sample text

[edit]Article 1 of theUniversal Declaration of Human Rightsin Bosnian, written in theCyrillic script:[70]

- Сва људска бића рађају се слободна и једнака у достојанству и правима. Она су обдарена разумом и свијешћу и треба да једно према другоме поступају у духу братства.

Article 1 of theUniversal Declaration of Human Rightsin Bosnian, written in theLatin alphabet:[71]

- Sva ljudska bića rađaju se slobodna i jednaka u dostojanstvu i pravima. Ona su obdarena razumom i sviješću i treba da jedno prema drugome postupaju u duhu bratstva.

Article 1 of theUniversal Declaration of Human Rightsin English:[72]

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^abCyrillic is an officially recognized alphabet, but in practice it is mainly used inRepublika Srpska,whereas in theFederation of Bosnia and Herzegovinamainly Latin is used.[2]

- ^Further information:List of Serbo-Croatian words of Turkish origin

References

[edit]- ^BosnianatEthnologue(27th ed., 2024)

- ^Alexander 2006,pp. 1–2.

- ^"Language and alphabet Article 13".Constitution of Montenegro.WIPO.19 October 2007.

Serbian, Bosnian, Albanian and Croatian shall also be in the official use.

- ^"World Atlas of Languages: Bosnian".en.wal.unesco.org.Retrieved2023-11-30.

- ^Dalby, David (1999).Linguasphere.53-AAA-g.Srpski+Hrvatski, Serbo-Croatian.Linguasphere Observatory.p. 445.

- ^Benjamin W. Fortson IV(2010).Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction(2nd ed.). Blackwell. p. 431.

Because of their mutual intelligibility, Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian are usually thought of as constituting one language called Serbo-Croatian.

- ^Blažek, Václav.On the Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey(PDF).pp. 15–16.Retrieved2021-10-26.

- ^Šipka, Danko(2019).Lexical layers of identity: words, meaning, and culture in the Slavic languages.New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 206.doi:10.1017/9781108685795.ISBN978-953-313-086-6.LCCN2018048005.OCLC1061308790.S2CID150383965.

Serbo-Croatian, which features four ethnic variants: Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin

- ^Mader Skender, Mia (2022). "Schlussbemerkung" [Summary].Die kroatische Standardsprache auf dem Weg zur Ausbausprache[The Croatian standard language on the way to ausbau language](PDF)(Dissertation). UZH Dissertations (in German). Zurich: University of Zurich, Faculty of Arts, Institute of Slavonic Studies. pp. 196–197.doi:10.5167/uzh-215815.Retrieved8 June2022.

Serben, Kroaten, Bosnier und Montenegriner immer noch auf ihren jeweiligen Nationalsprachen unterhalten und problemlos verständigen. Nur schon diese Tatsache zeigt, dass es sich immer noch um eine polyzentrische Sprache mit verschiedenen Varietäten handelt.

- ^Ćalić, Jelena (2021)."Pluricentricity in the classroom: the Serbo-Croatian language issue for foreign language teaching at higher education institutions worldwide".Sociolinguistica: European Journal of Sociolinguistics.35(1). De Gruyter: 113–140.doi:10.1515/soci-2021-0007.ISSN0933-1883.S2CID244134335.

The debate about the status of the Serbo-Croatian language and its varieties has recently shifted (again) towards a position which looks at the internal variation within Serbo-Croatian through the prism of linguistic pluricentricity

- ^Kordić, Snježana(2024)."Ideology Against Language: The Current Situation in South Slavic Countries"(PDF).InNomachi, Motoki;Kamusella, Tomasz(eds.).Languages and Nationalism Instead of Empires.Routledge Histories of Central and Eastern Europe. London:Routledge.pp. 168–169.doi:10.4324/9781003034025-11.ISBN978-0-367-47191-0.OCLC1390118985.S2CID259576119.SSRN4680766.COBISS.SR125229577.COBISS171014403.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-10.Retrieved2024-01-23.

- ^SeeArt. 6 of the Constitution of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina,available at the official website of Office of the High Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- ^"European charter for regional or minority languages: Application of the charter in Serbia"(PDF).Council of Europe.2009. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2014-01-03.

- ^ab"Vlada Crne Gore".Archived fromthe originalon 2009-06-17.Retrieved2009-03-18.See Art. 13 of the Constitution of the Republic of Montenegro, adopted on 19 October 2007, available at the website of the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Montenegro

- ^Driton Muharremi and Samedin Mehmeti (2013).Handbook on Policing in Central and Eastern Europe.Springer. p. 129.ISBN9781461467205.

- ^Tomasz Kamusella (15 January 2009).The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe.Palgrave Macmillan.ISBN978-0-230-55070-4.

In addition, today, neither Bosniaks nor Croats, but only Serbs use Cyrillic in Bosnia.

- ^Algar, Hamid (2 July 1994).Persian Literature in Bosnia-Herzegovina.Oxford. pp. 254–68.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Balić, Smail (1978).Die Kultur der Bosniaken, Supplement I: Inventar des bosnischen literarischen Erbes in orientalischen Sprachen.Vienna: Adolf Holzhausens, Vienna. p. 111.

- ^Balić, Smail (1992).Das unbekannte Bosnien: Europas Brücke zur islamischen Welt.Cologne, Weimar and Vienna: Bohlau. p. 526.

- ^Nosovitz, Dan (11 February 2019)."What Language Do People Speak in the Balkans, Anyway?".Atlas Obscura.Archivedfrom the original on 11 February 2019.Retrieved6 May2019.

- ^Zanelli, Aldo (2018).Eine Analyse der Metaphern in der kroatischen Linguistikfachzeitschrift Jezik von 1991 bis 1997[Analysis of Metaphors in Croatian Linguistic JournalLanguagefrom 1991 to 1997]. Studien zur Slavistik; 41 (in German). Hamburg: Kovač. pp. 21, 83.ISBN978-3-8300-9773-0.OCLC1023608613.(NSK).(FFZG)

- ^Radio Free Europe – Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Or Montenegrin? Or Just 'Our Language'?Živko Bjelanović: Similar, But Different, Feb 21, 2009, accessed Oct 8, 2010

- ^"Collection of printed books in Arabic, Turkish and Persian".Gazi Husrev-begova biblioteka.2014-05-16. Archived fromthe originalon 2014-05-17.Retrieved2014-05-16.

- ^Alexander 2006,p. 409.

- ^Greenberg, Robert D. (2004).Language and Identity in the Balkans: Serbo-Croatian and Its Disintegration.Oxford University Press. p. 136.ISBN9780191514555.

- ^"ISO 639-2 Registration Authority".Library of Congress.

- ^Sussex, Roland (2006).The Slavic Languages.Cambridge University Press. pp.76.ISBN0-521-22315-6.

- ^"Bosnian".Glottolog.

- ^"Bosnian".Ethnologue.

- ^Bernard Comrie (ed.): The World's Major Languages. Second Edition. Routledge, New York/London, 2009

- ^"Spring 2016 Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian W1202 section 001".Columbia University.Archived fromthe originalon 2016-01-28.

- ^"BCS 1133 – Continuing Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian I – Acalog ACMS™".Cornell University.

- ^"Courses".University of Chicago.

- ^"Bosnian Croatian Serbian".University of Washington.Archived fromthe originalon 2017-10-11.Retrieved2015-08-26.

- ^"Why Study Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian (BCS) with the KU Slavic Department?".University of Kansas.2012-12-18.

- ^"Institut für Slawistik » Curricula".University of Vienna.

- ^"Bosnisch/Kroatisch/Serbisch".University of Graz.Archived fromthe originalon 2016-07-03.Retrieved2015-08-26.

- ^"Slavistik – Bosnisch-Kroatisch-Montenegrinisch-Serbisch".University of Trier.28 July 2015.

- ^"13. Stanovništvo prema materinskom jeziku, po gradovima/općinama, popis 2001".Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2001.Zagreb:Croatian Bureau of Statistics.2002.

- ^"3. Stanovništvo prema materinskom jeziku – detaljna klasifikacija – popis 2011".Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011.Zagreb:Croatian Bureau of Statistics.December 2012.RetrievedJanuary 19,2014.

- ^"[Projekat Rastko] Odbor za standardizaciju srpskog jezika".rastko.rs.

- ^Svein Mønnesland, »Language Policy in Bosnia-Herzegovina« (pp 135–155). In:Language: Competence–Change–Contact = Sprache: Kompetenz – Kontakt – Wandel,edited by: Annikki Koskensalo, John Smeds, Rudolf de Cillia, Ángel Huguet; Berlin; Münster: Lit Verlag, 2012,ISBN978-3-643-10801-2,p. 143. "Already in 1990 the Committee for the Serbian language decided that only the term 'Bosniac language' should be used officially in Serbia, and this was confirmed in 1998."

- ^"Constitution of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina".High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina.Archived fromthe originalon 1 March 2002.Retrieved3 June2010.

- ^Decision on Constitutional Amendments in the Federation,High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina,archived fromthe originalon May 13, 2002,retrievedJanuary 19,2014

- ^Washington Agreement(PDF),retrievedJanuary 19,2014

- ^"The Constitution of the Republika Srpska".U.S. English Foundation Research. Archived fromthe originalon 21 July 2011.Retrieved3 June2010.

- ^"Decision on Constitutional Amendments in Republika Srpska".High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina.Archived fromthe originalon 18 January 2012.Retrieved3 June2010.

- ^Greenberg, Robert David (2004).Language and Identity in the Balkans: Serbo-Croatian and its Disintegration.Oxford University Press. pp.156.ISBN0-19-925815-5.

- ^Rizvanovic, Alma (2 August 2005)."Language Battle Divides Schools".Institute for War & Peace Reporting.Archived fromthe originalon 28 January 2012.Retrieved3 June2010.

- ^"Crna Gora dobila novi Ustav".Cafe del Montenegro. 20 October 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 2007-10-21.Retrieved12 August2017.

- ^abMuhsin Rizvić (1996).Bosna i Bošnjaci: Jezik i pismo(PDF).Sarajevo:Preporod. p. 6.

- ^Aleksandar Solovjev,Trgovanje bosanskim robljem do god. 1661.- Glasnik Zemaljskog muzeja, N. S., 1946, 1, 151.

- ^V. Putanec,Leksikografija,Enciklopedija Jugoslavije, V, 1962, 504.

- ^Muhsin Rizvić (1996).Bosna i Bošnjaci: Jezik i pismo(PDF).Sarajevo:Preporod. p. 7.

- ^Ivan Lovrenović (2012-01-30)."DIVKOVIĆ: OTAC BOSANSKE KNJIŽEVNOSTI, PRVI BOSANSKI TIPOGRAF".IvanLovrenovic.com. Archived fromthe originalon 12 July 2012.Retrieved30 August2012.

- ^hrvatska-rijec.com (17 April 2011)."Matija Divković – otac bosanskohercegovačke i hrvatske književnosti u BiH"(in Serbo-Croatian). www.hrvatska-rijec.com. Archived fromthe originalon 17 January 2012.Retrieved30 August2012.

- ^abMuhsin Rizvić (1996).Bosna i Bošnjaci: Jezik i pismo(PDF).Sarajevo:Preporod. p. 24.

- ^"Aljamiado and Oriental Literature in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1463-1878)"(PDF).pozitiv.si. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2014-02-02.

- ^abMuhsin Rizvić (1996).Bosna i Bošnjaci: Jezik i pismo(PDF).Sarajevo:Preporod. p. 8.

- ^abVatroslav Jagić,Iz prošlost hrvatskog jezika.Izabrani kraći spisi. Zagreb, 1948, 49.

- ^Alberto Fortis(1774).Viaggo in Dalmazia.Vol. I.Venice:Presso Alvise Milocco, all' Appoline, MDCCLXXIV. pp. 91–92.

- ^"str165".Archived fromthe originalon 2012-04-25.Retrieved2014-01-09.

- ^Matija Mažuranić(1842).Pogled u Bosnu.Zagreb:Tiskom narodne tiskarnice dra, Lj. Gaja. p. 52.

- ^Ivan Franjo Jukić(Slavoljub Bošnjak) (1851).Pogled u Bosnu.Zagreb:Bérzotiskom narodne tiskarnice dra. Ljudevita Gaja. p. 16.

- ^Ivan Kukuljević Sakcinski(1858).Putovanje po Bosni.Zagreb:Tiskom narodne tiskarnice dra, Lj. Gaja. p. 114.

- ^Cvetkovic, Ljudmila; Vezic, Goran (28 March 2009)."Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Or Montenegrin? Or Just 'Our Language'?".Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.Radio Free Europe.

- ^Šipka, Danko(2019).Lexical layers of identity: words, meaning, and culture in the Slavic languages.New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 166.doi:10.1017/9781108685795.ISBN978-953-313-086-6.LCCN2018048005.OCLC1061308790.S2CID150383965.

- ^Sotirović 2014,p. 48.

- ^Archived atGhostarchiveand theWayback Machine:Halilović, Senahid(26 April 2018)."Halilović za N1: Dužni smo osluškivati javnu riječ"[Halilović for N1: We Have to Listen to the Public Word].TV show N1 na jedan (host Nikola Vučić)(in Serbo-Croatian). Sarajevo:N1 (TV channel).Retrieved26 November2019.(6-13 minute)

- ^"Universal Declaration of Human Rights - Bosnian (Cyrillic)".unicode.org.

- ^"Universal Declaration of Human Rights - Bosnian (Latin)".unicode.org.

- ^"Universal Declaration of Human Rights".United Nations.

Sources and further reading

[edit]- Alexander, Ronelle (2006).Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, a Grammar: With Sociolinguistic Commentary.Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 1–2.ISBN9780299211936.

- Gröschel, Bernhard(2001). "Bosnisch oder Bosniakisch?" [Bosnian or Bosniak?]. In Waßner, Ulrich Hermann (ed.).Lingua et linguae. Festschrift für Clemens-Peter Herbermann zum 60. Geburtstag.Bochumer Beitraäge zur Semiotik, n.F., 6 (in German). Aachen: Shaker. pp. 159–188.ISBN978-3-8265-8497-8.OCLC47992691.

- Kafadar, Enisa (2009)."Bosnisch, Kroatisch, Serbisch – Wie spricht man eigentlich in Bosnien-Herzegowina?"[Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian – How do people really speak in Bosnia-Herzegovina?]. In Henn-Memmesheimer, Beate; Franz, Joachim (eds.).Die Ordnung des Standard und die Differenzierung der Diskurse; Teil 1(in German). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. pp. 95–106.ISBN9783631599174.OCLC699514676.

- Kordić, Snježana(2005)."I dalje jedan jezik"[Still one language].Sarajevske Sveske(in Serbo-Croatian) (10). Sarajevo: 83–89.ISSN1512-8539.SSRN3432980.CROSBI 430085.ZDB-ID2136753-X.Archivedfrom the original on 21 September 2013.Retrieved22 August2014.(COBISS-BH)[permanent dead link].

- —— (2011)."Jezična politika: prosvjećivati ili zamagljivati?"[Language policy: to clarify or to obscure?](PDF).In Gavrić, Saša (ed.).Jezička/e politika/e u Bosni i Hercegovini i njemačkom govornom području: zbornik radova predstavljenih na istoimenoj konferenciji održanoj 22. marta 2011. godine u Sarajevu(in Serbo-Croatian). Sarajevo: Goethe-Institut Bosnien und Herzegowina; Ambasada Republike Austrije; Ambasada Švicarske konfederacije. pp. 60–66.ISBN978-9958-1959-0-7.OCLC918205883.SSRN3434489.CROSBI 565627.Archived(PDF)from the original on 25 September 2013.(ÖNB).

- Sotirović, V.B. (2014)."Bosnian Language and ITS Inauguration: The Fate of the Former Serbocroat or Croatoserb Language".Sustainable Multilingualism.3(3): 47–61.doi:10.7220/2335-2027.3.5.

This article incorporatespublic domain materialfromThe World Factbook(2024 ed.).CIA.(Archived 2006 edition.)

This article incorporatespublic domain materialfromThe World Factbook(2024 ed.).CIA.(Archived 2006 edition.)

External links

[edit]- Basic Bosnian Phrases

- Learn Bosnian – List of Online Bosnian CoursesArchived2017-05-14 at theWayback Machine

- English–Bosnian dictionaryon Glosbe

- Gramatika bosanskoga jezika za srednje škole. Dio 1. i 2., Nauka o glasovima i oblicima.Sarajevo: National government of Bosnia and Hercegovina, National Printing House. 1890.

- Буквар: за основне школе у вилаjету босанском.Sarajevo: Vilayet Printing House. 1867.