Jin Chinese

| Jin | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tấn ngữ/Tấn ngữ Tấn phương ngôn/Tấn phương ngôn | |||||||||||||||||||||

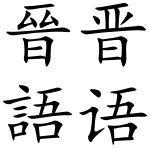

Jinyuwritten inChinese characters(vertically, traditional Chinese on the left, simplified Chinese on the right) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Native to | China | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Region | most ofShanxiprovince; centralInner Mongolia;parts ofHebei,Henan,Shaanxi | ||||||||||||||||||||

Native speakers | 48 million (2021)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Language codes | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 639-3 | cjy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Glottolog | jiny1235 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-c | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Tấn ngữ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Tấn ngữ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Sơn tây thoại | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Sơn tây thoại | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Shanxi speech | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Jin(simplified Chinese:Tấn ngữ;traditional Chinese:Tấn ngữ;pinyin:Jìnyǔ) is a group ofChinese linguistic varietiesspoken by roughly 48 million people in northernChina,[1]including most ofShanxiprovince, much of centralInner Mongolia,and adjoining areas inHebei,Henan,andShaanxiprovinces. The status of Jin is disputed among linguists; some prefer to include it withinMandarin,but others set it apart as a closely related but separate sister group.

Classification

[edit]After the concept ofMandarin Chinesewas proposed, the Jin dialects were universally included within it, mainly because Chinese linguists paid little attention to these dialects at the time. In order to promote Standard Mandarin in the early days ofPeople's Republic of China,linguists started to research various dialects in Shanxi, comparing these dialects with Standard Mandarin for helping the locals to learn it more quickly. During this period, a few linguists discovered some unique features of Jin Chinese that do not exist in other northern Mandarin dialects, planting the seeds for the future independence of Jin Chinese. Finally, in 1985,Li Rongproposed that Jin should be considered a separate top-level dialect group, similar toYueorWu.His main criterion was that Jin dialects had preserved theentering toneas a separate category, still marked with a glottal stop as in the Wu dialects, but distinct in this respect from most other Mandarin dialects. Some linguists have adopted this classification. However, others disagree that Jin should be considered a separate dialect group for these reasons:[2][3]

- Use of the entering tone as a diagnostic feature is inconsistent with the way that all other Chinese dialect groups have been delineated based on the reflexes of theMiddle Chinesevoiced initials.

- Certain other Mandarin dialects also preserve the glottal stop, especially theJianghuaidialects, and so far, no linguist has claimed that these dialects should also be split from Mandarin.

Dialects

[edit]TheLanguage Atlas of Chinadivides Jin into the following eight groups:[4]

- Bingzhou group(Chinese:Tịnh châu phiến), spoken in centralShanxi(the ancientBing Province), includingTaiyuan.Most dialects under this group can distinguish the light entering tone from the dark one, with only 1 level tone. In many dialects, especially those to the south of Taiyuan, the voiced obstruents from Middle Chinese become tenuis in all 4 tones, namely [b] → [p], [d] → [t] and [g] → [k].

- Lüliang group(Chinese:Lữ lương phiến), spoken in western Shanxi (includingLüliang) and northernShaanxi.Dialects under this group can differentiate light entering tone from dark entering tone. In most dialects, the voiced obstruents from Middle Chinese become aspirated in both level and entering tones, namely [b] → [pʰ], [d] → [tʰ] and [g] → [kʰ].

- Shangdang group(simplified Chinese:Thượng đảng phiến;traditional Chinese:Thượng đảng phiến), spoken in the area ofChangzhi(ancientShangdang) in southeastern Shanxi. Dialects under this group can differentiate light entering tone from dark entering tone. The palatalization of velar consonants does not occur in some dialects.

- Wutai group(simplified Chinese:Ngũ đài phiến;traditional Chinese:Ngũ đài phiến), spoken in parts of northern Shanxi (includingWutai County) and centralInner Mongolia.A few Dialects under this group can differentiate light entering tone from dark entering tone, while the others cannot. The fusion of the level tone and the rising one occurred in some dialects, though some linguists claim every dialect under this group has this feature.[5]

- Da-Bao group(Chinese:Đại bao phiến), spoken in parts of northern Shanxi and central Inner Mongolia, includingBaotou.

- Zhangjiakou–Hohhot group(simplified Chinese:Trương hô phiến;traditional Chinese:Trương hô phiến), spoken inZhangjiakouin northwesternHebeiand parts of central Inner Mongolia, includingHohhot.

- Han-Xin group(Chinese:Hàm tân phiến), spoken in southeastern Shanxi, southern Hebei (includingHandan) and northernHenan(includingXinxiang).

- Zhi-Yan group(Chinese:Chí diên phiến), spoken inZhidan CountyandYanchuan Countyin northern Shaanxi.

TheTaiyuan dialectfrom the Bingzhou group is sometimes taken as a convenient representative of Jin because many studies of this dialect are available, but most linguists agree that the Taiyuan vocabulary is heavily influenced by Mandarin, making it unrepresentative of Jin.[6]The Lüliang group is usually regarded as the "core" of the Jin language group as it preserves most archaic features of Jin. However, there is no consensus as to which dialect among the Lüliang group is the representative dialect.

Phonology

[edit]Unlike most varieties ofMandarin,Jin has preserved a finalglottal stop,which is the remnant of a finalstop consonant(/p/,/t/or/k/). This is in common with theEarly Mandarinof theYuan dynasty(c. 14th century AD) and with a number of modern southern varieties of Chinese. In Middle Chinese, syllables closed with a stop consonant had no tone. However, Chinese linguists prefer to categorize such syllables as belonging to a separate tone class, traditionally called the "entering tone".Syllables closed with aglottal stopin Jin are still toneless, or alternatively, Jin can be said to still maintain the entering tone. In standard Mandarin Chinese, syllables formerly ending with a glottal stop have been reassigned to one of the other tone classes in aseemingly random fashion.

Initials

[edit]| Labial | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | ||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tɕ | ||

| aspirated | tsʰ | tɕʰ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ɕ | x |

| voiced | v | z | ɣ | ||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||

| Approximant | l | ||||

- [ŋ]is mainly used in finals.

| Labial | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Retroflex | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | ||

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tɕ | tʂ | ||

| aspirated | tsʰ | tɕʰ | tʂʰ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ɕ | ʂ | x |

| voiced | v | z | ʐ | |||

| prenasal | nᵈz | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ɳ | ŋ | |

| Approximant | l | |||||

- The nasal consonant sounds may vary between nasal sounds[m,n,ɲ,ɳ,ŋ]or prenasalised stop sounds[ᵐb,ⁿd,ᶯɖʐ,ᶮdʲ,ᵑɡ].

- A prenasalised affricated fricative sound/nᵈz/,is also present.

Finals

[edit]| Oral | Nasal | Check | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | ∅ | coda | a | e | i | u | ŋ | æ̃ | ɛ̃ | ∅ | ∅ | ə | a | |

| Nucleus | ∅ | ei | ɒŋ | æ̃ | ɒ̃ | ɐʔ | əʔ | aʔ | ||||||

| Vowel | i | ia | ie | iŋ | iɛ̃ | iɒ̃ | iəʔ | iaʔ | ||||||

| y | ye | yŋ | yɛ̃ | yəʔ | ||||||||||

| a | ai | au | ||||||||||||

| əu | əŋ | |||||||||||||

| oŋ | ||||||||||||||

| ɤ | uɤ | |||||||||||||

| u | ua | uŋ | uæ̃ | uɒ̃ | uəʔ | uaʔ | ||||||||

| Triphthong | iəu | uai | uei | iau | iəŋ | |||||||||

| yəŋ | ||||||||||||||

| uəŋ | ||||||||||||||

| Syllabic | ɹ̩ | əɹ̩ | ||||||||||||

| Oral | Nasal | Check | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | ∅ | lab. | coda | a | i | u | ŋ | ã | ∅ | ∅ | a | ə | |

| Nucleus | ∅ | ɑu | ã | ə̃ | eʔ | aʔ | əʔ | ||||||

| Vowel | i | iɔ | ia | iu | iã | ĩ | ieʔ | iaʔ | |||||

| y | yɔ | ya | yŋ | yã | yeʔ | yaʔ | |||||||

| ei | eu | eŋ | |||||||||||

| a | ai | ||||||||||||

| iə̃ | |||||||||||||

| ɔ | |||||||||||||

| o | ou | oŋ | |||||||||||

| ɤu | |||||||||||||

| ɯ | iɯ | ||||||||||||

| u | uɔ | ua | ui | uŋ | uã | ueʔ | uaʔ | uəʔ | |||||

| Triphthong | iai | uai | uei | iɑu | |||||||||

| iou | uoŋ | ||||||||||||

| Syllabic | ɹ̩ | ɹ̩ʷ | əɹ̩ | ||||||||||

- The diphthong/ɤu/may also be realized as a monophthong close central vowel[ʉ].

- Sounds ending in the sequence/-aʔ/may also be heard as[-ɛʔ],then realized as[ɛʔ,iɛʔ,yɛʔ,uɛʔ].

- /y/can also be heard as a labio-palatal approximant[ɥ]when preceding initial consonants.

- /i/when occurring after alveolar sounds/ts,tsʰ,s/can be heard as an alveolar syllabic[ɹ̩],and is heard as a retroflex syllabic[ɻ̩]when occurring after retroflex consonants/tʂ,tʂʰ,ʂ,ʐ/.

Tones

[edit]Jin employs extremely complextone sandhi,or tone changes that occur when words are put together into phrases. The tone sandhi of Jin is notable in two ways among Chinese varieties:

- Tone sandhi rules depend on the grammatical structure of the words being put together. Hence, an adjective–noun compound may go through different sets of changes compared to a verb–object compound.[11]

- There are Jin varieties in which the "dark level" tone category (yīnpíngÂm bình ) and "light level" (yángpíngDương bình ) tone have merged in isolation but can still be distinguished in tone sandhi contexts. That is, while e.g. Standard Mandarin has a tonal distinction between Tone 1 and Tone 2, corresponding words in Jin Chinese may have the same tone when pronounced separately. However, these words can still be distinguished in connected speech. For example, in Pingyao Jin, dark leveltouThâu 'secretly' andtingThính 'to listen' on the one hand, and light leveltaoĐào 'peach' andhongHồng 'red' on the other hand, all have the same rising tone [˩˧] when pronounced in isolation. Yet, when these words are combined intotoutingThâu thính 'eavesdropping' andtaohongĐào hồng 'peach red', the tonal distinction emerges. Intouting,touhas a falling tone [˧˩] andtinghas a high-rising tone [˧˥], whereas both syllables intaohongstill have the same low-rising tone [˩˧] as in isolation.[12]

- According to Guo (1989)[13]and also noted by Sagart (1999), the departing (qushengKhứ thanh ) tone category in the Jin dialect ofXiaoyiis characterized by -ʰ and a high falling tone [˥˧]. Xiaoyi also lacks a voicing split in the level tone.[14]The rising (shangshengThượng thanh ) tone in Xiaoyi is also "characterized by a glottal break in the middle of the syllable [˧˩ʔ˩˨]".[15]

Grammar

[edit]Jin readily employs prefixes such asKhất/kəʔ/,Hắc/xəʔ/,Hốt/xuəʔ/,andNhập( nhật )/ʐəʔ/,in a variety ofderivationalconstructions. For example:

NhậpQuỷ"fool around" <Quỷ"ghost, devil"

In addition, there are a number of words in Jin that evolved, evidently, by splitting a mono-syllabic word into two, adding an 'l' in between (cf.Ubbi Dubbi,but with/l/instead of/b/). For example:

- /pəʔləŋ/<Bính/pəŋ/"hop"

- /tʰəʔluɤ/<Tha/tʰuɤ/"drag"

- /kuəʔla/<Quát/kua/"scrape"

- /xəʔlɒ̃/<Hạng/xɒ̃/"street"

A similar process can in fact be found in most Mandarin dialects (e.g.Quật lungkulong <Khổngkong), but it is especially common in Jin.

This may be a kind of reservation for double-initials inOld Chinese,although this is still controversial. For example, the characterKhổng(pronounced/kʰoːŋ/in Mandarin) which appears more often asQuật lung/kʰuəʔluŋ/in Jin, had the pronunciation like/kʰloːŋ/inOld Chinese.[citation needed]

Some dialects of Jin make a three-way distinction indemonstratives.(Modern English, for example, has only a two-way distinction between "this" and "that", with "yon" being archaic.)[citation needed]

Vocabulary

[edit]Lexical diversity in Jin Chinese is obvious, with some words having a very distinct regionality. Usually, there are more unique words in the core dialects than in the non-core dialects and moreover, some cannot be represented in Chinese characters.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^abJinatEthnologue(26th ed., 2023)

- ^Yan 2006,pp. 60–61, 67–69.

- ^Kurpaska 2010,pp. 74–75.

- ^Kurpaska 2010,p. 68.

- ^Fan, Huiqin phạm tuệ cầm (2015)."Jìn yǔ wǔ tái piàn yīn píng hé shàng shēng de fèn hé jí qí yǎn biàn"Tấn ngữ ngũ đài phiến âm bình hòa thượng thanh đích phân hợp cập kỳ diễn biến[The separation and combination of level and rising tones in Wutai dialects of Jin Chinese and their evolution].Ngữ văn nghiên cứu(3): 28–32.

Văn chương nhận vi tấn ngữ ngũ đài phiến âm bình hòa thượng thanh đích phân hợp hữu hân châu hình hòa ninh võ hình lưỡng cá loại hình, bất đồng loại hình dĩ cập bất đồng phương ngôn điểm đích cộng thời soa dị phản ánh xuất lưỡng cá thanh điều đích lịch thời diễn biến quá trình thị tiệm tiến thức đích, hợp lưu thị thanh điều vãn kỳ diễn biến đích kết quả, điều trị tương cận thị hợp lưu đích trực tiếp động nhân..

- ^Qiao, Quansheng kiều toàn sinh."Jìn fāngyán yánjiū de lìshǐ, xiànzhuàng yǔ wèilái"Tấn phương ngôn nghiên cứu đích lịch sử, hiện trạng dữ vị lai[The History, Current State and Future of the Research on Jin Chinese](PDF).p. 10.

Thái nguyên phương ngôn đích từ hối dữ kỳ tha phương ngôn bỉ giác, kết quả nhận vi tấn phương ngôn đích từ hối dữ quan thoại phương ngôn phi thường tiếp cận.

- ^abWen, Duanzheng ôn đoan chính; Shen, Ming thẩm minh (1999). Hou, Jingyi hầu tinh nhất (ed.).Tàiyuánhuà yīndàngThái nguyên thoại âm đương[The Sound System of the Taiyuan Dialect] (in Chinese). Shanghai: Shanghai jiaoyu chubanshe. pp. 4–12.

- ^ab"[ phần dương phương ngôn ngữ âm giáo trình ] đệ ngũ khóa - phần dương thoại bính âm phương án ([Fenyang Dialect Phonetics Course] Lesson 5 - Fenyang Dialect Pinyin Scheme)".2017.Retrieved2022-04-11.

- ^Xia, Liping; Hu, Fang (2016).Vowels and Diphthongs in the Taiyuan Jin Chinese Dialect.Interspeech 2016. pp. 993–997.doi:10.21437/Interspeech.2016-249.

- ^Juncheng, Zhao (1989).Phần dương thoại dữ phổ thông thoại giản biên [A Compendium of Fenyang and Mandarin].Sơn tây tỉnh phần dương huyện chí bạn công thất [Shanxi Province Fenyang County Office]. pp. 1–3.

- ^Chen, Matthew (2000).Tone Sandhi: Patterns across Chinese Dialects.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 93.ISBN0521033403.

- ^Chen, Matthew (2000).Tone Sandhi: Patterns across Chinese Dialects.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 51.ISBN0521033403.

- ^Guo, Jianrong quách kiến vinh (1989). Xiaoyi fangyan zhi hiếu nghĩa phương ngôn chí. Beijing: Yuwen.

- ^Sagart, Laurent (1999)."The origin of Chinese tones".Proceedings of the Symposium/Cross-Linguistic Studies of Tonal Phenomena/Tonogenesis, Typology and Related Topics.Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.Retrieved2024-06-15.

- ^Sagart, Laurent (2022-11-15)."Audio files of some shangsheng thượng thanh words in Xiaoyi hiếu nghĩa dialect (Shanxi), in the pronunciation of Prof. Guo Jianrong quách kiến vinh, Oct. 1985".Sino-Tibetan-Austronesian.Hypotheses.doi:10.58079/UKDO.Retrieved2024-06-15.

Sources

[edit]- Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS)(2012),Zhōngguó Yǔyán Dìtújí (Dì 2 bǎn): Hànyǔ fāngyán juǎnTrung quốc ngữ ngôn địa đồ tập ( đệ 2 bản ): Hán ngữ phương ngôn quyển[Language Atlas of China (2nd Edition): Chinese Dialect Volume] (in Chinese (China)), Beijing:The Commercial Press.

- Hou hầu, Jingyi tinh nhất; Shen thẩm, Ming minh (2002), Hou, Jingyi (ed.),Hiện đại hán ngữ phương ngôn khái luận[Overview of Modern Chinese Dialects] (in Chinese (China)), Shanghai Education Publishing House,ISBN7-5320-8084-6

- Kurpaska, Maria (2010),Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism ofThe Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects,De Gruyter Mouton,ISBN978-3-11-021914-2

- Yan, Margaret Mian (2006),Introduction to Chinese Dialectology,LINCOM Europa,ISBN978-3-89586-629-6.