Mazurka

TheMazurka(Polish:mazurek) is a Polish musical form based on stylisedfolk dancesintriple meter,usually at a lively tempo, with character defined mostly by the prominentmazur's "strongaccentsunsystematically placed on the second or thirdbeat".[2]The Mazurka, alongside thepolkadance, became popular at theballroomsand salons of Europe in the 19th century, particularly through the notable works byFrédéric Chopin.The mazurka (in Polishmazur,the same word as themazur) and mazurek (rural dance based on the mazur) are often confused in Western literature as the same musical form.[3]

History

[edit]The folk origins of theMazurkare three Polish folk dances which are:

- mazur,most characteristic due to its inconsistent rhythmic accents,

- slow and melancholickujawiak,

- fastoberek.

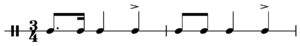

Themazurkais always found to have either a triplet, trill, dotted eighth note (quaver) pair, or an ordinary eighth note pair before twoquarter notes(crotchets). In the 19th century, the form became popular in manyballroomsin different parts of Europe.

"Mazurka" is a Polish word, it means aMasovianwoman or girl. It is afeminineform of the word "Mazur", which — until the nineteenth century — denoted an inhabitant of Poland'sMazoviaregion (Masovians,formerly plural:Mazurzy). The similar word "Mazurek" is adiminutiveandmasculineform of "Mazur". In relation to dance, all these words (mazur, mazurek, mazurka) mean "a Mazovian dance". Apart from the ethnic name, the wordmazurekrefers to various terms in Polish, e.g. acake,abirdand a popular surname.

Mazurekis also a rural dance identified by some as theoberek.It is saidoberekis a danced variation of the sungmazurek,the latter also having more prominent accents on second and third beats and less fluent of a rhythmical flow, which is so characteristical ofoberek.[4]

Severalclassicalcomposers have written mazurkas, with the best known being the59composed byFrédéric Chopinfor solo piano. In 1825,Maria Szymanowskawrote the largest collection of piano mazurkas published before Chopin.Henryk Wieniawskialso wrote two for violin with piano (the popular "Obertas", Op. 19),Julian Cochrancomposed a collection of five mazurkas for solo piano and orchestra, and in the 1920s,Karol Szymanowskiwrote a set of twenty for piano and finished his composing career with a final pair in 1934.Alexander Scriabin,who was at first conscious of being Chopin's follower, wrote 24 mazurkas.

Chopin first started composing mazurkas in 1824, but his composing did not become serious until 1830, the year of theNovember Uprising,a rebellion inCongress Polandagainst Russia. Chopin continued composing them until 1849, the year of his death. The stylistic and musical characteristics of Chopin's mazurkas differ from the traditional variety because Chopin in effect created a completely separate and new genre of mazurka all his own. For example, he used classical techniques in his mazurkas, includingcounterpointandfugue.[5]By including more chromaticism and harmony in the mazurkas, he made them more technically interesting than the traditional dances. Chopin also tried to compose his mazurkas in such a way that they could not be used for dancing, so as to distance them from the original form.

However, while Chopin changed some aspects of the original mazurka, he maintained others. His mazurkas, like the traditional dances, contain a great deal of repetition: repetition of certain measures or groups of measures; of entire sections; and of an initial theme.[6]The rhythm of his mazurkas also remains very similar to that of earlier mazurkas. However, Chopin also incorporated the rhythmic elements of the two other Polish forms mentioned above, thekujawiakandoberek;his mazurkas usually feature rhythms from more than one of these three forms (mazurek,kujawiak,andoberek). This use of rhythm suggests that Chopin tried to create a genre that had ties to the original form, but was still something new and different.

The mazurka began as a dance for either four or eight couples. Eventually,Michel Fokinecreated a female solo mazurka dance dominated by flyinggrandes jetés,alternating second and third arabesque positions, and split-leg climactic postures.[7]

Outside Poland

[edit]The form was common as a popular dance in Europe and the United States in the mid to late nineteenth century.

Cape Verde Islands

[edit]InCape Verdethe mazurka is also revered as an important cultural phenomenon played with acoustic bands led by a violinist and accompanied by guitarists. It also takes a variation of the mazurka dance form and is found mostly in the north of the archipelago, mainly inSão Nicolau,Santo Antão.In the south it finds popularity in the island ofBrava.

Czechia

[edit]CzechcomposersBedřich Smetana,Antonín Dvořák,andBohuslav Martinůall wrote mazurkas to at least some extent. For Smetana and Martinů, these are single pieces (respectively, a Mazurka-Cappricio for piano and a Mazurka-Nocturne for a mixed string/wind quartet), whereas Dvořák composed a set of six mazurkas for piano, and a mazurka for violin and orchestra.

France

[edit]In France,ImpressionisticcomposersClaude DebussyandMaurice Ravelboth wrote mazurkas; Debussy's is a stand-alone piece, and Ravel's is part of a suite of an early work,La Parade.Jacques Offenbachincluded a mazurka in his balletGaîté Parisienne;Léo Delibescomposed one which appears several times in the first act of his balletCoppélia.The mazurka appears frequently in French traditional folk music. In theFrench Antilles,the mazurka has become an important style of dance and music.

A creolised version of the mazurka ismazoukwhich—beginning around 1979 in Paris—morphed into the globally popular dance style “zouk”developed in France and popularised by Paris's Island-creole supergroupKassav';mazoukhad been introduced to the French Caribbean in the late 1800s. In the 21st century in Brazil and the Afro-Caribbean diaspora,zouk(and its progenitor band Kassav') remains very popular. In popular 20th century folk dancing in France, the Polish/classical-piano (seeChopin)mazurkaevolved intomazouk,a dance at a more gentle pace (without the traditional 'hop' step on the 3rd beat), fostering more-intimate dancing and associating mazouk with a "seduction" dance (see alsotangofrom Argentina). This "sexy" style of mazurka has also been imported to “balfolk"dancing inBelgiumand theNetherlands,hence the name "Belgian Mazurka" or "Flemish Mazurka". Perhaps the most enduring style of intimate dancing music of this origin movedzoukfrom the 1980s–2000s into its wildly popular (especially in Brazil and Africa) slow-dancing variant calledzouk love,which remains a staple of French-Caribbean dance venues in Paris and elsewhere.

Ireland

[edit]Mazurkas constitute a distinctive part of thetraditional dance musicofCounty Donegal,Ireland. As a couple's dance, it is no longer popular. The Polish dance entered Ireland in the 1840s, but is not widely played outside of Donegal.[8]Unlike the Polish mazurek, which may have an accent on the second or third beat of a bar, the Irish mazurka (masúrcain theIrish language) is consistently accented on the second beat, giving it a unique feel.[9][10][11][12]Musician Caoimhín Mac Aoidh has written a book on the subject,From Mazovia to Meenbanad: The Donegal Mazurkas,in which the history of the musical and dance form is related.[13][14][15]Mac Aoidh tracked down 32 different mazurkas as played in Ireland.[16]

Italy

[edit]Mazurkas are part of Italian popular music including theLisciostyle. Typical of Italian mazurkas are groups of triplets, strong dotted rhythms, and phrase endings of two accented quarter notes and a rest, unlike a waltz.

Brazil

[edit]InBrazil,the composerErnesto Nazarethwrote a Chopinesque mazurka called "Mercedes" in 1917.Heitor Villa-Loboswrote a mazurka for classical guitar in a similar musical style to Polish mazurkas.

Cuba

[edit]InCuba,composerErnesto Lecuonawrote a piece titledMazurka en Glisadofor the piano, one of various commissions throughout his life.

Nicaragua

[edit]InNicaragua,Carlos Mejía Godoy y los de PalacaguinaandLos Soñadores de Saraguascamade a compilation of mazurkas from popular folk music, which are performed with aviolin de talalate,an indigenous instrument fromNicaragua.

Curaçao

[edit]InCuraçaothe mazurka was popular as dance music in the nineteenth century, as well as in the first half of the twentieth century. Several Curaçao-born composers, such asJan Gerard Palm,Joseph Sickman Corsen,Jacobo Palm,Rudolph PalmandWim Statius Muller,have written mazurkas.

Mexico

[edit]InMexico,composersRicardo CastroandManuel M Poncewrote mazurkas for the piano in a Chopin fashion, eventually mixing elements of Mexican folk dances.

Philippines

[edit]In thePhilippines,the mazurka is a popular form oftraditional dance.The Mazurka Boholana is one well-known Filipino mazurka.

Portugal

[edit]In Portugal the mazurka became one of the most popular traditional European dances through the first years of the annualAndanças,a traditional dances festival held nearbyCastelo de Vide.

Russia

[edit]In Russia, many composers wrote mazurkas for solo piano:Scriabin(26),Balakirev(7),Tchaikovsky(6).Borodinwrote two in hisPetite Suitefor piano;Mikhail Glinkaalso wrote two, although one is a simplified version ofChopin's Mazurka No. 13. Tchaikovsky also included mazurkas in his scores forSwan Lake,Eugene Onegin,andSleeping Beauty.Rachmaninoff's Morceaux de salon Op 10 includes a Mazurka in D-flat major as its 7th piece.

The mazurka was a common dance at the balls of theRussian Empireand it is depicted in many Russian novels and films. In addition to its mention inLeo Tolstoy'sAnna Kareninaas well as in a protracted episode inWar and Peace,the dance is prominently featured inIvan Turgenev's novelFathers and Sons.Arkady reserves the mazurka for Madame Odintsov with whom he is falling in love. During Russian balls, it was danced elegantly and famously by the TsarinaMaria Feodorovna,the second-to-last tsarina of the Russian empire before its collapse in 1918.[17]

Sweden

[edit]InSwedish folk music,the quaver or eight-notepolskahas a similar rhythm to the mazurka, and the two dances have a common origin. The international version of the mazurka was also introduced under that name during the nineteenth century.

United States

[edit]The mazurka survives in someold-timefiddle tunes, and also in earlyCajun music,though it has largely fallen out of Cajun music now. In the Southern United States it was sometimes known as a "mazuka". Polish Mazurka was danced in upstate New York in the 1950s and 1960s (similarly to the krakowiak, millennium of Christianity) in Polish community centers or social clubs, which can be found throughout the US. The polka remains the best known dance of the Nation of Poland and its people and is regularly danced at weddings, dance halls and public events (e.g., summers outdoors, barn dances) in US.[18]

California

[edit]In addition to being part of the repertoire ofIrish traditional music sessions,the mazurka has been played by a wide variety of cultural groups in California. The mazurka first came toAlta Californiaduringthe Spanish periodand danced amongCalifornios.[19]Later, the renowned guitaristManuel Y. Ferrer,who was born inBaja Californiato Spanish parents and learned guitar from a Franciscan friar inSanta Barbarabut made his career in theSan Francisco Bay Area,arranged mazurkas for the guitar.[20]During the early 20th century, the mazurka became part of the repertoire ofItalian Americanmusicians in San Francisco playing in theballo lisciostyle.[21]PianistSid LeProtti,an importantOakland-born early jazz musician on the west coast, stated that before jazz took off, he and other musicians inBarbary Coastclubs played mazurkas in addition towaltzes,two-steps,marches,polkas,andschottisches.[22]One mazurka, played on harmonica, was collected bySidney Robertson Cowellfor theWPACalifornia Folk Music Project in 1939 inTuolumne County.[23]

See also

[edit]- Mazur (dance)

- Bourrée

- Fandango

- Ländler

- Mazurkas (Chopin)

- Polish music

- Polonaise (dance)

- Polska (dance)

- Waltz

- Pols

Notes

[edit]- ^Blatter, Alfred (2007).Revisiting music theory: a guide to the practice,p.28.ISBN0-415-97440-2.

- ^Randel, D. M., Ed.,The New Harvard Dictionary of Music,Harvard University Press, 1986

- ^Pudelek, Janina; Sibilska, Joanna (January 1996)."The polish dancers visit St. Petersburg, 1851: A detective story".Dance Chronicle.19(2): 171–189.doi:10.1080/01472529608569240.ISSN0147-2526.

- ^Bienkowski, Andrzej, 1946- (2001).Ostatni wiejscy muzykanci: ludzie, obyczaje, muzyka.Warszawa: Prʹoszyʹnski i S-ka.ISBN83-7255-795-0.OCLC48796397.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Charles Rosen,The Romantic Generation(Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1995)

- ^Jeffrey Kallberg,The problem of repetition and return in Chopin's mazurkas,Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- ^Robert Greskovic (1998).Ballet 101: A Complete Guide to Learning and Loving the Ballet.Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 354.ISBN978-0-87910-325-5.

- ^Cooper, P. (1995). Mel Bay's Complete Irish Fiddle Player. Mel Bay Publications, Inc.: Pacific, p. 76-80

- ^Vallely, F. (1999). The Companion to Traditional Irish Music. New York University Press: New York, p. 231

- ^"Rhythm Definitions – Irish Traditional Music Tune Index".Irishtune.info. 5 December 2012.Retrieved26 June2013.

- ^"Irish Flute Tunes » Blog Archive » Masúrca Gan Ainm".Irishflute.podbean.com. 5 May 2007.Retrieved26 June2013.

- ^"Mazurka"(PDF)(Press release).Retrieved26 June2013.

- ^"Late session".Retrieved26 June2013.[dead link]

- ^[1]Archived27 May 2012 at theWayback Machine

- ^"9780955903106: From Mazovia to Meenbanad: The Donegal Mazurkas – AbeBooks – Mac Aoidh, Caoimhin: 0955903106".AbeBooks.Retrieved26 June2013.

- ^"Séamus Gibson Caoimhin mac Aoidh Niall Mac Aoidh Martin McGinley... • From Mazovia to Mennbanad • cdtrrracks".Cdtrrracks.com.Retrieved26 June2013.

- ^Tony Faber (2008).Fabergé's Eggs.Random House.ISBN9781400065509.

- ^Racino, Julie Ann. (2014). Reflections on community integration in rural communities in upstate New York. Rome, NY: Community and Policy Studies.

- ^Mende Grey, Vykki (2016).Dance Tunes from Mexican and Spanish California.San Diego, CA: Los Californios.

- ^Back, Douglas (2003).Hispanic-American Guitar.Mel-Bay. p. 9.ISBN9781610656139.

- ^Mignano Crawford, Sheri (2008).Mandolin Melodies(3rd ed.). Petaluma, CA: Zighi Baci. pp. 11–13.ISBN978-0976372233.

- ^Stoddard, Tom (1998).Jazz on the Barbary Coast.Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books. p.12.ISBN1-890771-04-X.

- ^Morgan, Aaron. Cowell, Sidney Robertson (ed.).Mazurka.California Gold: Northern California Folk Music from the Thirties Collected by Sidney Robertson Cowell.Library of Congress.Retrieved11 August2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Downes, Stephen. "Mazurka"Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 17 November 2009.

- Kallberg, Jeffrey. "The problem of repetition and return in Chopin's mazurkas." Chopin Styles, ed. Jim Samson. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Kallberg, Jeffrey. "Chopin's Last Style." Journal of the American Musicological Society 38.2 (1985): 264–315.

- Michałowski, Kornel, and Jim Samson. "Chopin, Fryderyk Franciszek"Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 17 November 2009. (esp. section 6," Formative Influences ")

- Milewski, Barbara. "Chopin's Mazurkas and the Myth of the Folk." 19th-Century Music 23.2 (1999): 113–35.

- Rosen, Charles. The Romantic Generation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Winokur, Roselyn M. "Chopin and the Mazurka". Diss. Sarah Lawrence College, 1974.

External links

[edit]- history, description, costumes, music, sources

- Mazurka within traditional dances of the County of Nice (France)

- The Russian Mazurka

- The Mazurka Project

- Halman, Johannes and Robert Rojer (2008).Jan Gerard Palm Music Scores: Waltzes, Mazurkas, Danzas, Tumbas, Polkas, Marches, Fantasies, Serenades, a Galop and Music Composed for Services in the Synagogue and the Lodge.Amsterdam:Broekmans & Van Poppel.*[2]

- 'Vincent Campbell's Mazurka' as played by Vincent Campbell in Co. Donegal