Nilutamide

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | nye-LOO-tah-mide[1] |

| Trade names | Nilandron, Anandron |

| Other names | RU-23908 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697044 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth[2] |

| Drug class | Nonsteroidal antiandrogen |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokineticdata | |

| Bioavailability | Good[2] |

| Protein binding | 80–84%[4] |

| Metabolism | Liver(CYP2C19,FMO)[2][4] |

| Metabolites | At least 5, some active[4][5] |

| Eliminationhalf-life | Mean: 56 hours (~2 days)[6] Range: 23–87 hours[6] |

| Excretion | Urine:62%[2][4] Feces:<10%[2][4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChemCID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard(EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.153.268 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

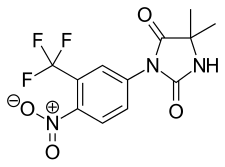

| Formula | C12H10F3N3O4 |

| Molar mass | 317.224g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 149 °C (300 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Nilutamide,sold under the brand namesNilandronandAnandron,is anonsteroidal antiandrogen(NSAA) which is used in the treatment ofprostate cancer.[8][9][10][11][12][13]It has also been studied as a component offeminizing hormone therapyfortransgender womenand to treatacneandseborrheain women.[14][15][16][17]It is takenby mouth.[4]

Side effectsin men includebreast tendernessandenlargement,feminization,sexual dysfunction,andhot flashes.[18][19][20][21]Nausea,vomiting,visual disturbances,alcohol intolerance,elevated liver enzymes,andlung diseasecan occur in both sexes.[21][22][19][23][24][25]Rarely, nilutamide can causerespiratory failureandliver damage.[18][21]These unfavorable side effects, along with a number of associated cases of death, have limited the use of nilutamide.[13][26][27]

Nilutamide acts as aselectiveantagonistof theandrogen receptor(AR), preventing the effects ofandrogensliketestosteroneanddihydrotestosterone(DHT) in the body.[28][14]Because most prostate cancercellsrely on thesehormonesforgrowthandsurvival,nilutamide can slow the progression of prostate cancer and extend life in men with the disease.[14]

Nilutamide was discovered in 1977 and was first introduced for medical use in 1987.[9][29][30][6]It became available in the United States in 1996.[31][32][33]The drug has largely been replaced by newer and improved NSAAs, namelybicalutamideandenzalutamide,due to their betterefficacy,tolerability,andsafety,and is now rarely used.[34]

It is on theWorld Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[35]

Medical uses

[edit]Prostate cancer

[edit]Nilutamide is used in prostate cancer in combination with agonadotropin-releasing hormone(GnRH)analogueat a dosage of 300 mg/day (150 mg twice daily) for the first 4 weeks of treatment, and 150 mg/day thereafter.[27][36]It is not indicated as amonotherapyin prostate cancer.[27]Only one small non-comparative study has assessed nilutamide as a monotherapy in prostate cancer.[37]

Nilutamide has been used to prevent the effects of thetestosteroneflare at the start of GnRH agonist therapy in men with prostate cancer.[38][39][40]

Transgender hormone therapy

[edit]Nilutamide has been studied for use as a component offeminizing hormone therapyfortransgender women.[14][15]It has been assessed in at least five smallclinical studiesfor this purpose in treatment-naive subjects.[15][41][42][43][44][45]In these studies, nilutamide monotherapy at a dosage of 300 mg/day, induced observable signs of clinicalfeminizationin young transgender women (age range 19–33 years) within 8 weeks,[42]includingbreast development,decreasedbody hair(though notfacial hair),[41]decreasedmorning erectionsandsex drive,[43]and positive psychological and emotional changes.[43][46]Signs of breast development occurred in all subjects within 6 weeks and were associated with increasednipple sensitivity,[45][42][43]and along with decreased hair growth, were the earliest sign of feminization.[42]

Nilutamide did not change the size of theprostate gland(which is the same as with high-dosagecyproterone acetateandethinylestradioltreatment for as long as 18 months), but was found to alter itshistology,including increasedstromal tissuewith a significant reduction inaciniand atrophicepithelial cells,indicating glandularatrophy.[44][45][47]In addition, readily apparent histological changes were observed in thetestes,including a reduction intubularandinterstitial cells.[44]

Nilutamide was found to more than doubleluteinizing hormone(LH) andtestosteronelevels and to tripleestradiollevels.[41][42][44]In contrast,follicle-stimulating hormonelevels remained unchanged.[42][44]A slight but significant increase inprolactinlevels was observed, and levels ofsex hormone-binding globulinincreased as well.[42][44]The addition of ethinylestradiol to nilutamide therapy after 8 weeks abolished the increase in LH, testosterone, and estradiol levels and dramatically suppressed testosterone levels, into thecastraterange.[41][42]Both nilutamide alone and the combination of nilutamide andestrogenwere regarded as resulting in effective and favorable antiandrogen action and feminization in transgender women.[41][42]

Skin conditions

[edit]Nilutamide has been assessed in the treatment ofacneandseborrheain women in at least one small clinical study.[16][17]The dosage used was 200 mg/day, and in the study, "seborrhea and acne decreased markedly within the first month and practically disappeared after 2 months of [nilutamide] treatment."[16][17]

Available forms

[edit]Nilutamide is available in the form of 50 and 150 mgoraltablets.[48]

Side effects

[edit]Generalside effectsof NSAAs, including nilutamide, includegynecomastia,breast pain/tenderness,hot flashes(67%),depression,fatigue,sexual dysfunction(including loss oflibidoanderectile dysfunction), decreasedmusclemass, and decreasedbonemass with an associated increase infractures.[19][20][21]Also,nausea(24–27%),vomiting,constipation(20%), andinsomnia(16%) may occur with nilutamide.[21]Nilutamide monotherapy is known to eventually induce gynecomastia in 40 to 80% of men treated with it for prostate cancer, usually within 6 to 9 months of treatment initiation.[49][50][51][52]

Relative to other NSAAs, nilutamide has been uniquely associated with mild and reversiblevisual disturbances(31–58%) includingdelayed ocular adaptation to darknessand impairedcolor vision,[22]adisulfiram-like[19]alcoholintolerance(19%),interstitial pneumonitis(0.77–2.4%)[34][53][54](which can result indyspnea(1%) as a secondary effect and can progress topulmonary fibrosis),[23]andhepatitis(1%), and has a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting compared to other NSAAs.[13][27][21][55]The incidence of interstitial pneumonitis with nilutamide has been found to be much higher inJapanesepatients (12.6%), warranting particular caution inAsianindividuals.[56][57]There is a case report of simultaneous liver and lung toxicity in a nilutamide-treated patient.[58]

There is also a risk ofhepatotoxicitywith nilutamide, though occurrence is very rare and the risk is significantly less than with flutamide.[6][59]The incidence of abnormalliver function tests(e.g.,elevated liver enzymes) has been variously reported as 2 to 33% with nilutamide.[60][1]For comparison, the risk of elevated liver enzymes has been reported as 4 to 62% in the case offlutamide.[60][24][6]The risk of hepatotoxicity with nilutamide has been described as far less than with flutamide.[1]Fulminant hepatic failurehas been reported for nilutamide, with fatal outcome.[6][61][62][63]Between 1986 and 2003, the numbers of published cases of hepatotoxicity for antiandrogens totaled 46 for flutamide, 21 forcyproterone acetate,4 for nilutamide, and 1 forbicalutamide.[64]Similarly to flutamide, nilutamide exhibitsmitochondrialtoxicityinhepatocytesby inhibitingrespiratory complex I(NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase) (though notrespiratory complexes II, III, or IV) in theelectron transport chain,resulting in reducedATPandglutathioneproduction and thus decreased hepatocyte survival.[63][65][66]Thenitrogroupof nilutamide has been theorized to be involved in both its hepatotoxicity and itspulmonary toxicity.[66][67]

| Class | Side effect | Nilutamide 150 mg/day + orchiectomy(n = 225) (%)a,b |

Placebo+orchi- ectomy(n = 232) (%)a,b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular system | Hypertension | 5.3 | 2.6 |

| Digestive system | Nausea | 9.8 | 6.0 |

| Constipation | 7.1 | 3.9 | |

| Endocrine system | Hot flashes | 28.4 | 22.4 |

| Metabolicandnutritional system | Increased aspartate transaminase | 8.0 | 3.9 |

| Increased alanine transaminase | 7.6 | 4.3 | |

| Nervous system | Dizziness | 7.1 | 3.4 |

| Respiratory system | Dyspnea | 6.2 | 7.3 |

| Special senses | Impaired adaptation to darkness | 12.9 | 1.3 |

| Abnormal vision | 6.7 | 1.7 | |

| Urogenital system | Urinary tract infection | 8.0 | 9.1 |

| Overall | 86 | 81 | |

| Footnotes:a=Phase IIIstudies ofcombined androgen blockade(nilutamide +orchiectomy) in men withadvanced prostate cancer.b= Incidence ≥5% regardless ofcausality.Sources:See template. | |||

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Antiandrogenic activity

[edit]| Compound | RBA[b] |

|---|---|

| Metribolone | 100 |

| Dihydrotestosterone | 85 |

| Cyproterone acetate | 7.8 |

| Bicalutamide | 1.4 |

| Nilutamide | 0.9 |

| Hydroxyflutamide | 0.57 |

| Flutamide | <0.0057 |

Notes:

| |

Nilutamide acts as aselectivecompetitivesilent antagonistof the AR (IC50= 412 nM),[28]which prevents androgens like testosterone and DHT from activating the receptor.[14]The affinity of nilutamide for the AR is about 1 to 4% of that of testosterone and is similar to that ofbicalutamideand2-hydroxyflutamide.[69][70][71]Similarly to 2-hydroxyflutamide, but unlike bicalutamide, nilutamide is able to weakly activate the AR at high concentrations.[70]It does not inhibit5α-reductase.[72]

Like other NSAAs such as flutamide and bicalutamide, nilutamide, without concomitant GnRH analogue therapy, increases serum androgen (by two-fold in the case of testosterone),estrogen,andprolactinlevels due to inhibition of AR-mediated suppression ofsteroidogenesisvianegative feedbackon thehypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis.[14]As such, though nilutamide is still effective as an antiandrogen as a monotherapy, it is given in combination with a GnRH analogue such asleuprorelinin prostate cancer to suppress androgen concentrations to castrate levels in order to attainmaximal androgen blockade(MAB).[14]

Like flutamide and bicalutamide, nilutamide is able to cross theblood–brain barrierand hascentralantiandrogen actions.[30]

| Species | IC50(nM) | RBA(ratio) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bicalutamide | 2-Hydroxyflutamide | Nilutamide | Bica/2-OH-flu | Bica/nilu | Ref | |

| Rat | 190 | 700 | ND | 4.0 | ND | [73] |

| Rat | ~400 | ~900 | ~900 | 2.3 | 2.3 | [74] |

| Rat | ND | ND | ND | 3.3 | ND | [75] |

| Rata | 3595 | 4565 | 18620 | 1.3 | 5.2 | [76] |

| Human | ~300 | ~700 | ~500 | 2.5 | 1.6 | [77] |

| Human | ~100 | ~300 | ND | ~3.0 | ND | [78] |

| Humana | 2490 | 2345 | 5300 | 1.0 | 2.1 | [76] |

| Footnotes:a= Controversial data.Sources:See template. | ||||||

Cytochrome P450 inhibition

[edit]Nilutamide is known to inhibit severalcytochrome P450enzymes, includingCYP1A2,CYP2C9,andCYP3A4,and can result in increased levels of medications that aremetabolizedby theseenzymes.[79]It has also been found to inhibit the enzymeCYP17A1(17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase)in vitroand thus thebiosynthesisof androgens.[80][81]However, nilutamide monotherapy significantly increases testosterone levelsin vivo,so the clinical significance of this finding is uncertain.[80][81]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Nilutamide has anelimination half-lifeof 23 to 87 hours, with a mean of 56 hours,[6]or about two days; this allows for once-daily administration.[13]Steady state(plateau) levels of the drug are attained after two weeks of administration with a dosage of 150 mg twice daily (300 mg/day total).[82]It ismetabolizedbyCYP2C19,with at least fivemetabolites.[5]Virtually all of the antiandrogenic activity of nilutamide comes from the parent drug (as opposed to metabolites).[83]

Chemistry

[edit]Nilutamide is structurally related to thefirst-generationNSAAsflutamideandbicalutamideas well as to thesecond-generationNSAAsenzalutamideandapalutamide.

History

[edit]Nilutamide was developed byRousseland was first described in 1977.[9][29][30]It was first introduced for medical use in 1987 inFrance[6][84]and was the second NSAA to be marketed, with flutamide preceding it and bicalutamide following it in 1995.[13][85]It was not introduced until 1996 in theUnited States.[31][32][33]

Society and culture

[edit]Generic names

[edit]Nilutamideis thegeneric nameof the drug and itsINN,USAN,BAN,andDCF.[9][10][11][12]

Brand names

[edit]Nilutamide is marketed under the brand name Nilandron in theUnited Statesand under the brand name Anandron elsewhere in the world such as inAustralia,Canada,Europe,andLatin America.[10][12]

Availability

[edit]Nilutamide is or has been available in the United States, Canada, Australia, Europe, Latin America,Egypt,andLebanon.[10][12]In Europe, it is or has been available inBelgium,Croatia,theCzech Republic,Finland,France,theNetherlands,Norway,Poland,Portugal,Serbia,Sweden,Switzerland,andYugoslavia.[10][12]in Latin America, it is or has been available inArgentina,Brazil,andMexico.[10][12]

Research

[edit]The combination of anestrogenand nilutamide as a form ofcombined androgen blockadefor the treatment of prostate cancer has been studied in animals.[86]

Nilutamide has been studied in the treatment of advanced breast cancer.[87][88]

References

[edit]- ^abc"Nilutamide - LiverTox".National Institutes of Health.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2018.Retrieved24 September2018.

In large registration clinical trials, ALT elevations occurred in 2% to 33% of patients during nilutamide therapy. The elevations were usually mild, asymptomatic and transient, rarely requiring drug discontinuation. In rare instances, clinically apparent acute liver injury has occurred during nilutamide therapy, but the number of published cases are few, and the agent appears to be far less hepatotoxic than flutamide.

- ^abcdePerry MC, Doll DC, Freter CE (30 July 2012).Perry's The Chemotherapy Source Book.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 711–.ISBN978-1-4698-0343-2.

- ^"FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)".nctr-crs.fda.gov.FDA.Retrieved22 October2023.

- ^abcdefLemke TL, Williams DA (24 January 2012).Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1373–.ISBN978-1-60913-345-0.

- ^abChabner BA, Longo DL (8 November 2010).Cancer Chemotherapy and Biotherapy: Principles and Practice.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 680–.ISBN978-1-60547-431-1.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved12 October2016.

- ^abcdefghKolvenbag GJ, Furr BJ (2009). "Nonsteroidal Antiandrogens". In Jordan VC, Furr HJ (eds.).Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer.Humana Press. pp. 347–368.doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-152-7_16.ISBN978-1-60761-471-5.

Although the t1/2 of nilutamide is h (mean 56 h) (39), suggesting that once-daily dosing would be appropriate, a three times per day regimen has been employed in most clinical trials.

- ^"Nilutamide (Nilandron) Use During Pregnancy".Archivedfrom the original on 28 October 2020.Retrieved20 July2016.

- ^"NILANDRON® (nilutamide)"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 30 March 2021.Retrieved25 September2018.

- ^abcdElks J (14 November 2014).The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies.Springer. pp. 873–.ISBN978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^abcdefIndex Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory.Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 737–.ISBN978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^abMorton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012).Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 199–.ISBN978-94-011-4439-1.

- ^abcdef"Nilutamide".Archivedfrom the original on 2 December 2020.Retrieved14 November2017.

- ^abcdeDenis LJ, Griffiths K, Kaisary AV, Murphy GP (1 March 1999).Textbook of Prostate Cancer: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment.CRC Press. pp. 280–.ISBN978-1-85317-422-3.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved21 February2016.

- ^abcdefgDenis L (6 December 2012).Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer: A Key to Tailored Endocrine Treatment.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 194–210.ISBN978-3-642-45745-6.

- ^abcKreukels BP, Steensma TD, De Vries AL (1 July 2013).Gender Dysphoria and Disorders of Sex Development: Progress in Care and Knowledge.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 280–.ISBN978-1-4614-7441-8.

- ^abcCouzinet B, Thomas G, Thalabard JC, Brailly S, Schaison G (July 1989). "Effects of a pure antiandrogen on gonadotropin secretion in normal women and in polycystic ovarian disease".Fertility and Sterility.52(1): 42–50.doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60786-0.PMID2744186.

- ^abcNamer M (October 1988). "Clinical applications of antiandrogens".Journal of Steroid Biochemistry.31(4B): 719–729.doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90023-4.PMID2462132.

- ^abDole EJ, Holdsworth MT (January 1997). "Nilutamide: an antiandrogen for the treatment of prostate cancer".The Annals of Pharmacotherapy.31(1): 65–75.doi:10.1177/106002809703100112.PMID8997470.S2CID20347526.

- ^abcdDart RC (2004).Medical Toxicology.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 521–.ISBN978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ^abDeAngelis LM, Posner JB (12 September 2008).Neurologic Complications of Cancer.Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 479–.ISBN978-0-19-971055-3.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved21 February2016.

- ^abcdefLehne RA (2013).Pharmacology for Nursing Care.Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1297–.ISBN978-1-4377-3582-6.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved12 October2016.

- ^abBecker KL (2001).Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1196–.ISBN978-0-7817-1750-2.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved12 October2016.

- ^abWein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC,Partin AW,Peters CA (25 August 2011).Campbell-Walsh Urology: Expert Consult Premium Edition: Enhanced Online Features and Print, 4-Volume Set.Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2939–.ISBN978-1-4160-6911-9.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved21 February2016.

- ^abHussain S, Haidar A, Bloom RE, Zayouna N, Piper MH, Jafri SM (2014)."Bicalutamide-induced hepatotoxicity: A rare adverse effect".The American Journal of Case Reports.15:266–270.doi:10.12659/AJCR.890679.PMC4068966.PMID24967002.

- ^Boarder MR, Newby D, Navti P (25 March 2010).Pharmacology for Pharmacy and the Health Sciences: A Patient-centred Approach.OUP Oxford. pp. 632–.ISBN978-0-19-955982-4.Archivedfrom the original on 6 July 2024.Retrieved12 October2016.

- ^DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, eds. (18 March 2016).Prostate and Other Genitourinary Cancers: Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology.Wolters Kluwer Health. pp. 1006–.ISBN978-1-4963-5421-1.

- ^abcdChang C (1 January 2005).Prostate Cancer: Basic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches.World Scientific. pp. 11–.ISBN978-981-256-920-2.

- ^abSingh SM, Gauthier S, Labrie F (February 2000). "Androgen receptor antagonists (antiandrogens): structure-activity relationships".Current Medicinal Chemistry.7(2): 211–247.doi:10.2174/0929867003375371.PMID10637363.

- ^abLabrie F, Lagacé L, Ferland L, Kelly PA, Drouin J, Massicotte J, et al. (1978)."Interactions Between LHRH, Sex Steroids and" Inhibin "in the Control of LH and FSH Secretion".International Journal of Andrology.1(s2a): 81–101.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.1978.tb00008.x.ISSN0105-6263.

- ^abcRaynaud JP, Bonne C, Bouton MM, Lagace L, Labrie F (July 1979). "Action of a non-steroid anti-androgen, RU 23908, in peripheral and central tissues".Journal of Steroid Biochemistry.11(1A): 93–99.doi:10.1016/0022-4731(79)90281-4.PMID385986.

- ^abPavlik EJ (6 December 2012).Estrogens, Progestins, and Their Antagonists: Health Issues.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 167–.ISBN978-1-4612-4096-9.

- ^abBohl CE, Gao W, Miller DD, Bell CE, Dalton JT (April 2005)."Structural basis for antagonism and resistance of bicalutamide in prostate cancer".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.102(17): 6201–6206.Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.6201B.doi:10.1073/pnas.0500381102.PMC1087923.PMID15833816.

- ^ab"Nilutamide - AdisInsight".Archivedfrom the original on 5 May 2021.Retrieved26 June2017.

- ^abGulley JL (2011).Prostate Cancer.Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 81–.ISBN978-1-935281-91-7.

- ^World Health Organization(2021).World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021).Geneva: World Health Organization.hdl:10665/345533.WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^Upfal J (2006).The Australian Drug Guide: Every Person's Guide to Prescription and Over-the-counter Medicines, Street Drugs, Vaccines, Vitamins and Minerals...Black Inc. pp. 283–.ISBN978-1-86395-174-6.

- ^Anderson J (March 2003). "The role of antiandrogen monotherapy in the treatment of prostate cancer".BJU International.91(5): 455–461.doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2003.04026.x.PMID12603397.S2CID8639102.

Trial experience with nilutamide monotherapy is limited to one small non-comparative study involving 26 patients with metastatic disease given nilutamide 100 mg three times daily (the dose used when nilutamide is administered as a component of MAB) [14]. The median progression-free survival in these patients was 9 months, with a median overall survival of 23 months. There have been no comparative trials of nilutamide with other antiandrogens or with castration [15]. The limited available data on nilutamide monotherapy means that no meaningful conclusions about the role of nilutamide in this setting can be determined. Nilutamide is not licensed as monotherapy.

- ^Thompson IM (2001)."Flare Associated with LHRH-Agonist Therapy".Reviews in Urology.3(Suppl 3): S10–S14.PMC1476081.PMID16986003.

- ^Scaletscky R, Smith JA (April 1993). "Disease flare with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues. How serious is it?".Drug Safety.8(4): 265–270.doi:10.2165/00002018-199308040-00001.PMID8481213.S2CID36964191.

- ^Kuhn JM, Billebaud T, Navratil H, Moulonguet A, Fiet J, Grise P, et al. (August 1989). "Prevention of the transient adverse effects of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue (buserelin) in metastatic prostatic carcinoma by administration of an antiandrogen (nilutamide)".The New England Journal of Medicine.321(7): 413–418.doi:10.1056/NEJM198908173210701.PMID2503723.

- ^abcdeAsscheman H, Gooren LJ, Peereboom-Wynia JD (September 1989). "Reduction in undesired sexual hair growth with anandron in male-to-female transsexuals--experiences with a novel androgen receptor blocker".Clinical and Experimental Dermatology.14(5): 361–363.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1989.tb02585.x.PMID2612040.S2CID45303518.

- ^abcdefghiRao BR, de Voogt HJ, Geldof AA, Gooren LJ, Bouman FG (October 1988). "Merits and considerations in the use of anti-androgen".Journal of Steroid Biochemistry.31(4B): 731–737.doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90024-6.PMID3143862.

- ^abcdvan Kemenade JF, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Cohen L, Gooren LJ (June 1989). "Effects of the pure antiandrogen RU 23.903 (anandron) on sexuality, aggression, and mood in male-to-female transsexuals".Archives of Sexual Behavior.18(3): 217–228.doi:10.1007/BF01543196.PMID2751416.S2CID44664956.

- ^abcdefGooren L, Spinder T, Spijkstra JJ, van Kessel H, Smals A, Rao BR, Hoogslag M (April 1987). "Sex steroids and pulsatile luteinizing hormone release in men. Studies in estrogen-treated agonadal subjects and eugonadal subjects treated with a novel nonsteroidal antiandrogen".The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.64(4): 763–770.doi:10.1210/jcem-64-4-763.PMID3102546.

- ^abcde Voogt HJ, Rao BR, Geldof AA, Gooren LJ, Bouman FG (1987). "Androgen action blockade does not result in reduction in size but changes histology of the normal human prostate".The Prostate.11(4): 305–311.doi:10.1002/pros.2990110403.PMID2960959.S2CID84632739.

- ^Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren LJ (1993). "The Influence of Hormone Treatment on Psychological Functioning of Transsexuals".Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality.5(4): 55–67.doi:10.1300/J056v05n04_04.ISSN0890-7064.S2CID145237890.

- ^Drugs & Aging.Adis International. 1993.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved2 April2018.

In 16 male subjects undergoing androgen blockade with nilutamide 100 to 300 mg/day for 8 weeks for male to female gender reassignment, prostate volume was not changed (de Voogt et al. 1987).

- ^Meyers RA (2 March 2018).Translational Medicine: Molecular Pharmacology and Drug Discovery.Wiley. pp. 46–.ISBN978-3-527-68719-0.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved2 August2018.

- ^Bautista-Vidal C, Barnoiu O, García-Galisteo E, Gómez-Lechuga P, Baena-González V (2014). "Treatment of gynecomastia in patients with prostate cancer and androgen deprivation".Actas Urologicas Espanolas.38(1): 34–40.doi:10.1016/j.acuroe.2013.10.002.PMID23850393.

[...] the frequency of gynecomastia with antiandrogens in monotherapy is [...] around [...] 79% with nilutamide [...]

- ^Deepinder F, Braunstein GD (September 2012). "Drug-induced gynecomastia: an evidence-based review".Expert Opinion on Drug Safety.11(5): 779–795.doi:10.1517/14740338.2012.712109.PMID22862307.S2CID22938364.

Treatment with estrogen has the highest incidence of gynecomastia, at 40 – 80%, anti-androgens, including flutamide, bicalutamide and nilutamide, are next, with a 40 – 70% incidence, followed by GnRH analogs (goserelin, leuprorelin) and combined androgen deprivation [...]

- ^Michalopoulos NV, Keshtgar MR (October 2012). "Images in clinical medicine. Gynecomastia induced by prostate-cancer treatment".The New England Journal of Medicine.367(15): 1449.doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1209166.PMID23050528.

Gynecomastia occurs in up to 80% of patients who receive nonsteroidal antiandrogens (eg, bicalutamide, flutamide, or nilutamide), usually within the first 6 to 9 months after the initiation of treatment.

- ^Di Lorenzo G, Autorino R, Perdonà S, De Placido S (December 2005). "Management of gynaecomastia in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review".The Lancet. Oncology.6(12): 972–979.doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70464-2.PMID16321765.

- ^Camus P, Rosenow III EC (29 October 2010).Drug-induced and Iatrogenic Respiratory Disease.CRC Press. pp. 235–.ISBN978-1-4441-2869-7.

- ^Held-Warmkessel J (2006).Contemporary Issues in Prostate Cancer: A Nursing Perspective.Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 257–.ISBN978-0-7637-3075-8.

- ^Ramon J, Denis LJ (5 June 2007).Prostate Cancer.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 229–.ISBN978-3-540-40901-4.

- ^Mahler C (1996). "A Review of the Clinical Studies with Nilutamide".Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer.pp. 105–111.doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45745-6_10.ISBN978-3-642-45747-0.

Akaza had to prematurely terminate a nilutamide study in Japan as 12.6% of his patients developed interstitial lung disease [4]. This complication has been mainly observed in Japan and much less in other trials worldwide.

- ^Micromedex (1 January 2003).USP DI 2003: Drug Information for Healthcare Professionals.Thomson Micromedex. pp. 220–224.ISBN978-1-56363-429-1.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved12 October2016.

- ^Gomez JL, Dupont A, Cusan L, Tremblay M, Tremblay M, Labrie F (May 1992). "Simultaneous liver and lung toxicity related to the nonsteroidal antiandrogen nilutamide (Anandron): a case report".The American Journal of Medicine.92(5): 563–566.doi:10.1016/0002-9343(92)90756-2.PMID1580304.

- ^Aronson JK (21 February 2009).Meyler's Side Effects of Endocrine and Metabolic Drugs.Elsevier. pp. 150–.ISBN978-0-08-093292-7.

- ^abMcLeod DG (1997)."Tolerability of Nonsteroidal Antiandrogens in the Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer".The Oncologist.2(1): 18–27.doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2-1-18.PMID10388026.

Incidences of abnormal liver function test results have been variously reported from 2%-33% in nilutamide groups [13, 32, 33, 45] and from 4%-62% in flutamide groups [5, 7, 9, 11, 34, 38-40, 48] in trials of monotherapy and CAB.

- ^Aronson JK (2011).Side Effects of Drugs Annual: A Worldwide Yearly Survey of New Data in Adverse Drug Reactions.Elsevier. pp. 874–.ISBN978-0-444-53741-6.

- ^Marty F, Godart D, Doermann F, Mérillon H (1996). "[Fatal fulminating hepatitis caused by nilutamide. A new case]".Gastroenterologie Clinique et Biologique(in French).20(8–9): 710–711.PMID8977826.

- ^abMerwat SN, Kabbani W, Adler DG (April 2009). "Fulminant hepatic failure due to nilutamide hepatotoxicity".Digestive Diseases and Sciences.54(4): 910–913.doi:10.1007/s10620-008-0406-8.PMID18688719.S2CID27421870.

In addition, nilutamide is noted to exhibit mitochondrial toxicity by inhibiting complex I activity of the mitochondrial respiratory chain leading to the impairment of ATP formation and the biosynthesis of glutathione, thereby possibly predisposing the liver to toxicity [13].

- ^Chitturi S, Farrell GC (2013). "Adverse Effects of Hormones and Hormone Antagonists on the Liver".Drug-Induced Liver Disease.Vol. 3. pp. 605–619.doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-387817-5.00033-9.ISBN9780123878175.PMID11096606.

Liver injury is well recognized with all antiandrogens (Table 33-3). Thus, among all published cases identified between 1986 and 2003, flutamide (46), cyproterone (21), nilutamide (4), and bicalutamide (1) were implicated [107,108].

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^Berson A, Schmets L, Fisch C, Fau D, Wolf C, Fromenty B, et al. (July 1994). "Inhibition by nilutamide of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and ATP formation. Possible contribution to the adverse effects of this antiandrogen".The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics.270(1): 167–176.PMID8035313.

- ^abCoe KJ, Jia Y, Ho HK, Rademacher P, Bammler TK, Beyer RP, et al. (September 2007)."Comparison of the cytotoxicity of the nitroaromatic drug flutamide to its cyano analogue in the hepatocyte cell line TAMH: evidence for complex I inhibition and mitochondrial dysfunction using toxicogenomic screening".Chemical Research in Toxicology.20(9): 1277–1290.doi:10.1021/tx7001349.PMC2802183.PMID17702527.

- ^Boelsterli UA, Ho HK, Zhou S, Leow KY (October 2006). "Bioactivation and hepatotoxicity of nitroaromatic drugs".Current Drug Metabolism.7(7): 715–727.doi:10.2174/138920006778520606.PMID17073576.

- ^Ayub M, Levell MJ (August 1989). "The effect of ketoconazole related imidazole drugs and antiandrogens on [3H] R 1881 binding to the prostatic androgen receptor and [3H]5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone and [3H]cortisol binding to plasma proteins".J. Steroid Biochem.33(2): 251–5.doi:10.1016/0022-4731(89)90301-4.PMID2788775.

- ^Gaillard M (1996). "Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics of Nilutamide in Animal and Man".Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer.pp. 95–103.doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45745-6_9.ISBN978-3-642-45747-0.

- ^abFigg W, Chau CH, Small EJ (14 September 2010).Drug Management of Prostate Cancer.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 71–.ISBN978-1-60327-829-4.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved12 October2016.

- ^Benni HJ, Vemer HM (15 December 1990).Chronic Hyperandrogenic Anovulation.CRC Press. pp. 153–.ISBN978-1-85070-322-8.

- ^Raynaud JP, Fiet J, Le Goff JM, Martin PM, Moguilewsky M, Ojasoo T (1987). "Design of antiandrogens and their mechanisms of action: a case study (anandron)".Hormone Research.28(2–4): 230–241.doi:10.1159/000180948.PMID3331376.

- ^Furr BJ, Valcaccia B, Curry B, Woodburn JR, Chesterson G, Tucker H (June 1987). "ICI 176,334: a novel non-steroidal, peripherally selective antiandrogen".The Journal of Endocrinology.113(3): R7–R9.doi:10.1677/joe.0.113R007.PMID3625091.

- ^Teutsch G, Goubet F, Battmann T, Bonfils A, Bouchoux F, Cerede E, Gofflo D, Gaillard-Kelly M, Philibert D (January 1994). "Non-steroidal antiandrogens: synthesis and biological profile of high-affinity ligands for the androgen receptor".The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.48(1): 111–119.doi:10.1016/0960-0760(94)90257-7.PMID8136296.S2CID31404295.

- ^Winneker RC, Wagner MM, Batzold FH (December 1989). "Studies on the mechanism of action of Win 49596: a steroidal androgen receptor antagonist".Journal of Steroid Biochemistry.33(6): 1133–1138.doi:10.1016/0022-4731(89)90420-2.PMID2615358.

- ^abLuo S, Martel C, Leblanc G, Candas B, Singh SM, Labrie C, Simard J, Bélanger A, Labrie F (1996). "Relative potencies of Flutamide and Casodex: preclinical studies".Endocrine Related Cancer.3(3): 229–241.doi:10.1677/erc.0.0030229.ISSN1351-0088.

- ^Ayub M, Levell MJ (August 1989). "The effect of ketoconazole related imidazole drugs and antiandrogens on [3H] R 1881 binding to the prostatic androgen receptor and [3H]5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone and [3H]cortisol binding to plasma proteins".Journal of Steroid Biochemistry.33(2): 251–255.doi:10.1016/0022-4731(89)90301-4.PMID2788775.

- ^Kemppainen JA, Wilson EM (July 1996). "Agonist and antagonist activities of hydroxyflutamide and Casodex relate to androgen receptor stabilization".Urology.48(1): 157–163.doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00117-3.PMID8693644.

- ^Ferrando SJ, Levenson JL, Owen JA (20 May 2010).Clinical Manual of Psychopharmacology in the Medically Ill.American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 256–.ISBN978-1-58562-942-8.

- ^abHarris MG, Coleman SG, Faulds D, Chrisp P (1993). "Nilutamide. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in prostate cancer".Drugs & Aging.3(1): 9–25.doi:10.2165/00002512-199303010-00002.PMID8453188.S2CID262029302.

- ^abAyub M, Levell MJ (July 1987). "Inhibition of rat testicular 17 alpha-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase activities by anti-androgens (flutamide, hydroxyflutamide, RU23908, cyproterone acetate) in vitro".Journal of Steroid Biochemistry.28(1): 43–47.doi:10.1016/0022-4731(87)90122-1.PMID2956461.

- ^Denis L (6 December 2012).Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer: A Key to Tailored Endocrine Treatment.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 202–.ISBN978-3-642-45745-6.

The plateau level of nilutamide (steady state) was obtained after about 14 days of repeated administration of the drug (150 mg b.i.d.) and did not depend upon intervals between doses.

- ^Mahler C, Verhelst J, Denis L (May 1998). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of the antiandrogens and their efficacy in prostate cancer".Clinical Pharmacokinetics.34(5): 405–417.doi:10.2165/00003088-199834050-00005.PMID9592622.S2CID25200595.

- ^Fischer J, Klein C, Childers WE (16 April 2018).Successful Drug Discovery.Wiley. pp. 98–.ISBN978-3-527-80868-7.

- ^Wellington K, Keam SJ (2006). "Bicalutamide 150mg: a review of its use in the treatment of locally advanced prostate cancer".Drugs.66(6): 837–850.doi:10.2165/00003495-200666060-00007.PMID16706554.S2CID46966712.

- ^Rao BR, Geldof AA, van der Wilt CL, de Voogt HJ (1988). "Efficacy and advantages in the use of low doses of Anandron and estrogen combination in the treatment of prostate cancer".The Prostate.13(1): 69–78.doi:10.1002/pros.2990130108.PMID3420036.S2CID23553575.

- ^Chia K, O'Brien M, Brown M, Lim E (February 2015)."Targeting the androgen receptor in breast cancer".Current Oncology Reports.17(2): 4.doi:10.1007/s11912-014-0427-8.PMID25665553.S2CID5174768.

- ^Millward MJ, Cantwell BM, Dowsett M, Carmichael J, Harris AL (May 1991)."Phase II clinical and endocrine study of Anandron (RU-23908) in advanced post-menopausal breast cancer".British Journal of Cancer.63(5): 763–764.doi:10.1038/bjc.1991.170.PMC1972372.PMID1903951.

Further reading

[edit]- Raynaud JP, Bonne C, Moguilewsky M, Lefebvre FA, Bélanger A, Labrie F (1984). "The pure antiandrogen RU 23908 (Anandron), a candidate of choice for the combined antihormonal treatment of prostatic cancer: a review".The Prostate.5(3): 299–311.doi:10.1002/pros.2990050307.PMID6374639.S2CID85417869.

- Moguilewsky M, Bertagna C, Hucher M (1987). "Pharmacological and clinical studies of the antiandrogen Anandron".Journal of Steroid Biochemistry.27(4–6): 871–875.doi:10.1016/0022-4731(87)90162-2.PMID3320565.

- Du Plessis DJ (1991). "Castration plus nilutamide vs castration plus placebo in advanced prostate cancer. A review".Urology.37(2 Suppl): 20–24.doi:10.1016/0090-4295(91)80097-q.PMID1992599.

- Creaven PJ, Pendyala L, Tremblay D (1991). "Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of nilutamide".Urology.37(2 Suppl): 13–19.doi:10.1016/0090-4295(91)80096-p.PMID1992598.

- Harris MG, Coleman SG, Faulds D, Chrisp P (1993). "Nilutamide. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in prostate cancer".Drugs & Aging.3(1): 9–25.doi:10.2165/00002512-199303010-00002.PMID8453188.S2CID262029302.

- Dole EJ, Holdsworth MT (January 1997). "Nilutamide: an antiandrogen for the treatment of prostate cancer".The Annals of Pharmacotherapy.31(1): 65–75.doi:10.1177/106002809703100112.PMID8997470.S2CID20347526.

- Iversen P, Melezinek I, Schmidt A (January 2001)."Nonsteroidal antiandrogens: a therapeutic option for patients with advanced prostate cancer who wish to retain sexual interest and function".BJU International.87(1): 47–56.doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00988.x.PMID11121992.S2CID28215804.