Renaissance fair

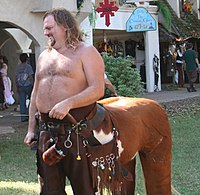

ARenaissanceormedieval fair(ren faire,orfestival) is an outdoor gathering that aims to entertain its guests by recreating a historical setting, most often theEnglish Renaissance.

Renaissance fairs generally include costumed entertainers or fair-goers, musical and theatrical acts, art and handicrafts for sale, and festival food. These fairs are open to the public and typically commercial. Some are permanent theme parks, while others are short-term events in a fairground, winery, or other large spaces.[1]Some Renaissance fairs offer campgrounds for those who wish to stay more than one day.[2]

Many Renaissance fairs are set during the reign of QueenElizabeth I of England.Some are set earlier, during the reign ofHenry VIII,or in other countries, such as France. Others are set outside the era of the Renaissance; these may include earliermedievalperiods such as theViking Ageor later periods such as theGolden Age of Piracy.Some engage in deliberate 'time travel' by encouraging participants to wear costumes representing several eras in a broad time period. Renaissance fairs encourage visitors to engage with costumes and audience participation, often renting outfits to fairgoers. Many welcome fantasy elements likewizardsandelves.[3]

Characteristics

[edit]

Most Renaissance fairs are arranged to represent an imagined English village during the reign ofElizabeth I,often thought of as the height of theEnglish Renaissance.

Within a modern Renaissance festival, there are stages or performance areas set up for scheduled shows, such as plays inShakespeareanorcommedia dell'artetraditions, as well asanachronisticaudience participation in comedy routines.[4]Other performances include dancers, magicians, musicians, jugglers, and singers. Between the stages, the streets ('lanes') are lined with stores ('shoppes') and stalls where independent vendors sell themed handcrafts, clothing, books, and artwork.[5]

Renaissance fairs typically feature a wide variety of foods inspired by bothmedieval cuisineand typical American fair foods likecorn dogs.[6][7]Some foods, like turkey legs, steak on a stick, andbread bowlshave become iconic of Renaissance festivals.[8][9][10]Beer,mead,and wine are also common.[11][12]

Games include typical fair events, such as archery, axe-throwing, anddunk tanks.Rides are typically not machine-powered; various animal rides and human-powered swings are common, as are live animal displays andfalconryexhibitions. Larger Renaissance fairs often include ajoustas a main attraction.PETAand Born Free USA have protested the use of elephants and camels at theMaryland Renaissance FestivalandArizona Renaissance Festival.[13][14]

In addition to staged performances, a major attraction of Renaissance fairs are professional and amateur crowds of actors who play historical figures, roaming the fairgrounds and interacting with visitors. Some allow visitors to bringpeace-bondedweapons, while others only allow fair employees to wear them. The Renaissance fair subculture's word for costumed guests is 'playtrons,' aportmanteauof the words player and patron. This adds enjoyment to guests' experience by 'getting into the act' as Renaissance Lords and Ladies, peasants, pirates, belly dancers, or fantasy characters. However, many Renaissance fairs discourage interaction between the official cast and so-called 'playtrons.'[citation needed]

Most fairs have an end-of-the-day ritual parade, dance, or concert where all employees gather and bid farewell to the patrons.

Renaissance fairs are staged around the world at different times of the year. Fair vendors, actors, and crew often work by going from event to event as one fair ends and another begins.

History in the United States

[edit]

In post-World War II America, there was a resurgence of interest inmedievalandRenaissance culture.Folk musician and traditionalistJohn Langstaffgained popularity in the 1950s as part of anearly music revivaltrend. In 1957, Langstaff hosted "A Christmas Masque of Traditional Revels" inNew York City,and another the following year inWashington, D.C.A televised version was broadcast on theHallmark Hall of Famein 1966 which includedDustin Hoffmanplaying the part of the dragon slain bySaint George.In 1971, Langstaff established a permanentChristmas RevelsinCambridge,Massachusetts.[15]

In 1963, Los Angeles schoolteacher Phyllis Patterson held a small Renaissance fair as a class activity, using the backyard of her Laurel Canyon home in the Hollywood Hills as the fairgrounds. On May 11 and 12 in the same year, Patterson and her husband,Ron Patterson,presented the first "Renaissance Pleasure Faire"as a one-weekend fundraiser for a radio stationKPFK,drawing some eight thousand people. The Living History Center designed the fair to resemble a springtime market fair of the period.[16]

Many original booths were free-of-charge reenactments of historical activities, including printing presses and blacksmiths. The first commercial vendors were artisans and food merchants, and had to demonstrate historical accuracy or plausibility for their wares. Volunteers were organized into "guilds" to focus on specific reenactment roles (musicians, military, Celtic clans, peasants, etc.). Both actors and vendors were required to stay "in character" while working by speaking with period language, accents, and mannerisms.[17]

The originalRenaissance Pleasure Faire of Southern California(RPFS) was held in the spring of 1966 at theParamount Ranchlocated in Agoura, California, focusing on the practices of old English springtime markets and "Maying" customs. In 1967, the Pattersons created a fall Renaissance fair with a harvest festival theme at what is nowChina Camp State Parkin San Rafael, California. The fall fair was moved in 1971 to theBlack PointForest inNovato, California.Both fairs developed into local traditions and began a movement that spread across the country.[18]

Althoughhistorical reenactmentsare not exclusive to the United States, Renaissance fairs are largely an American variation on the idea of reenactments. European historical fairs, such as those held atKentwell HallinSuffolk,England, operate more on theliving history museummodel, in which an actual historic site is staffed by reenactors who explain historical life to modern visitors, rather than acting in a role.[19]

In recent years, American-style Renaissance fairs have made inroads in other countries. Germany has seen avery similar phenomenonsince the 1980s, and fairs have grown increasingly popular in Canada and Australia since the mid-1990s.

Spinoffs of Renaissance fairs also include fairs set in other time periods, such asChristmas fairsset inCharles Dickens' London.[20]

Names

[edit]Renaissance fairs have several variant names, many of which use old-fashioned spellings such asfaireorfayre.These spellings originate from theMiddle Englishfeire(variant spellings includefeyre,faire,andfayre), which comes from the Anglo-French wordfeire.[21]They can also be referred to asElizabethan,Medieval,orTudorfairs or festivals.

A GermanMittelaltermarkt(literally "medieval market" ) resembles a Renaissance fair. Many Catalan towns holdMercats Medievals(literally "medieval markets" ) as part of their annual festivities.[22]

Internal debates

[edit]Within the Renaissance fair community, there are different opinions on the desirability of 'authenticity' at festivals. Some[who?]believe fairs should be as authentic an experience as possible, supplemented with educational aspects similar to Europeanliving history museums.[23]Others believe that entertainment is the primary goal. Richard Shapiro, who founded what later became theBristol Renaissance FaireoutsideChicagoin 1972, favored entertainment, saying "we were so authentic back then it was almost painful."[24]Festival organizers sometimes attempt a balance between authenticity and entertainment. In 1968, Phyllis Patterson, founder of theCalifornia Renaissance Pleasure Faires,also created the Living History Centre, a California-based educational and cultural foundation. The foundation's motto "we trick into learning with a laugh" reflects a belief in merging history and entertainment.[25]

See also

[edit]- List of Renaissance and Medieval fairs

- Medieval reenactment

- Renaissance Magazine

- Society for Creative Anachronism

Notes

[edit]- ^"State fairgrounds could benefit from fuller calendar",Battle Creek Enquirer,2007-09-05.

- ^"Louisiana",Renaissance Festival,archived fromthe originalon 2007-06-08.

- ^de Groot, Jerome (2009).Consuming History: Historians and Heritage in Contemporary Popular Culture.Routledge. p.120.ISBN978-0203889008.

- ^"Sir Guy of Warwick".Sir Guy of Warwick Official Site.

- ^Gillespie, Paul W."Maryland Renaissance Festival".Capital Gazette.Retrieved10 October2014.

- ^Vera-Phillips, Kris (2020-03-11)."Food Fit for a King? A Historian Reviews AZ Ren Fest and Medieval Times Menus".Phoenix New Times.Retrieved2020-12-23.

- ^Miller, Ally (July 24, 2020)."Pennsylvania Renaissance Faire will resume this fall for 40th anniversary season".www.phillyvoice.com.Retrieved2020-12-23.

- ^Foremand, Star (2018-05-17)."Renaissance Faire Food Is So Much More Than Giant Turkey Legs".LA Weekly.Retrieved2020-12-23.

- ^Cheryl (2020-09-02)."Tasty and Authentic Recipes For Your Renaissance Festival At Home".RenFest.org.Retrieved2020-12-23.

- ^"12 foods we love at the Renaissance Faire".San Gabriel Valley Tribune.2019-04-02.Retrieved2020-12-23.

- ^Geurts, Jimmy."Suncoast Renaissance Festival to debut at Sarasota Fairgrounds".Sarasota Herald-Tribune.Retrieved2020-12-23.

- ^KGO (2018-10-08)."Bay Area LIFE: Ren Faire food scene".ABC7 San Francisco.Retrieved2020-12-23.

- ^Gillespie, Paul W."Maryland Renaissance Festival".Capital Gazette.Retrieved10 October2014.

- ^"'PETA planning protest at Arizona Renaissance Festival ".21 February 2014.

- ^Derek Schofield (2006-03-10),"Obituary: Jack Langstaff",The Guardian,UK.

- ^Thomas, Peter; Kember, Michael; Sneed, Richard J (1987),The Faire: Photographs and History of the Renaissance Pleasure Faire from 1963 onwards,The Good Book Press.

- ^Fox, Margalit (January 30, 2011)."Ron Patterson, Renaissance (Fair) Man, Dies at 80".The New York Times.Retrieved18 January2016.

- ^Rubin, Rachel (2012).Well Met: Renaissance Faires and the American Counterculture.New York: New York University Press.ISBN9780814771389.

- ^Horsler, Val (2003),Living the Past,London,ENG,UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, in association with English Heritage,ISBN0-297-84312-5.

- ^Zavoral, Linda (24 November 2017)."Annual Dickens Fair chases the Scrooge away".The Mercury News.Bay Area News Group.Retrieved20 December2017.

- ^Kurath, Hans (1953), Lewis, Robert E (ed.),Middle English Dictionary,vol. 8, University of Michigan Press, p. 451,ISBN0472010611,retrieved2009-09-11.

- ^FestesMajors (2023-09-01)."▷ FIRES MEDIEVALS - Agenda de Fires Medievals 2022".Festes Majors de Catalunya - L'AGENDA DE FIRES I FESTES DE CATALUNYA(in Catalan).Retrieved2023-10-02.

- ^"Bristol Renaissance Faire for more than kings, queens",Star,Chicago Heights: Star newspapers, 2007-08-23, archived fromthe originalon 2007-09-27,

Bristol Renaissance Faire organizers strive for authenticity

. - ^"King Richard's Faire brings a Renaissance revival",The Providence Journal(online ed.), 2007-08-30, archived fromthe originalon 2008-05-28.

- ^"Home".Living History Centre.Retrieved2023-02-10..