Ricercar

Aricercar(/ˌriːtʃərˈkɑːr/REE-chər-KAR,Italian:[ritʃerˈkar]) orricercare(/ˌriːtʃərˈkɑːreɪ/REE-chər-KAR-ay,Italian:[ritʃerˈkaːre]) is a type of lateRenaissanceand mostly earlyBaroqueinstrumental composition. The termricercarderives from the Italian verbricercare,which means "to search out; to seek"; many ricercars serve apreludialfunction to "search out" thekeyormodeof a following piece. A ricercar may explore the permutations of a givenmotif,and in that regard may follow the piece used as illustration. The term is also used to designate anetudeor study that explores a technical device in playing an instrument, or singing.

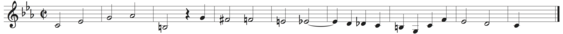

In its most common contemporary usage, it refers to an early kind offugue,particularly one of a serious character in which the subject uses longnote values.However, the term has a considerably more varied historical usage.

Among the best-known ricercars are the two forharpsichordcontained inBach'sThe Musical OfferingandDomenico Gabrielli's set of seven for solocello.The latter set contains what are considered to be some of the earliest pieces for solo cello ever written.[1]

Terminology

[edit]In the sixteenth century, the word ricercar could refer to several types of compositions. Terminology was flexible, even lax then: whether a composer called an instrumental piece atoccata,acanzona,afantasia,or a ricercar was clearly not a matter of strict taxonomy but a rather arbitrary decision. Yet ricercars fall into two general types: a predominantlyhomophonicpiece, with occasional runs and passagework, not unlike a toccata, found from the late fifteenth to the mid-sixteenth century, after which time this type of piece came to be called a toccata;[2]and from the second half of the sixteenth century onward, a sectional work in which each section beginsimitatively,usually in avariation form.The second type of ricercar, the imitative,contrapuntaltype, was to prove the more important historically, and eventually developed into the fugue.Marco Dall'Aquila(c. 1480–after 1538) was known forpolyphonicricercars.[3]

Examples of both types of ricercars can be found in the works ofGirolamo Frescobaldi,e.g. in hisFiori musicali.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Gödel, Escher, Bach:An Eternal Golden BraidbyDouglas Hofstadter,which includes a section entitled "Six-part Ricercar", after theRicercar a 6fromJ.S.Bach'sThe Musical Offering.

References

[edit]- ^Burgess Powell, Jemma.A performing edition of Gabrielli's 7 Ricercari for Violoncello Solo, with an historical investigation and recommendations for performance(PDF)(Thesis). p. 10.

- ^Arthur J. Ness, "Ricercar",Harvard Dictionary of Music,fourth edition, edited by Don Michael Randel (Cambridge: Belknap Press for Harvard University Press, 2003).

- ^Randel, Don Michael (1999).The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music and Musicians.[full citation needed]

Bibliography

[edit]- "Ricercar," "Fugue," "Counterpoint" inThe New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians,ed. Stanley Sadie. 20 vol. London, Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1980.ISBN1-56159-174-2.

- Gustave Reese,Music in the Renaissance.New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 1954.ISBN0-393-09530-4.

- Manfred Bukofzer,Music in the Baroque Era.New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 1947.ISBN0-393-09745-5.

- Ursula Kirkendale,"The Source for Bach'sMusical Offering,"Journal of the American Musicological Society33 (1980), 99–141.

- The New Harvard Dictionary of Music,ed. Don Randel. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1986.ISBN0-674-61525-5.

- Arthur J. Ness, "Ricercar",Harvard Dictionary of Music,fourth edition, edited by Don Michael Randel, 729–31. Harvard University Press Reference Library. Cambridge: Belknap Press for Harvard University Press, 2003.ISBN0-674-01163-5.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition ofricercarat Wiktionary

The dictionary definition ofricercarat Wiktionary- Petrucci Music Library Ricercar Collection