Scottish Highlands

Highlands

| |

|---|---|

Lowland–Highland divide | |

| Seat | Inverness |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 600,000 |

| [citation needed] | |

| Demonym | Highlander |

| Time zone | GMT/BST |

TheHighlands(Scots:the Hielands;Scottish Gaelic:a' Ghàidhealtachd[əˈɣɛːəl̪ˠt̪ʰəxk],lit. 'the place of theGaels') is ahistorical regionofScotland.[1][failed verification]Culturally, the Highlands and theLowlandsdiverged from theLate Middle Agesinto themodern period,whenLowland Scotslanguage replacedScottish Gaelicthroughout most of the Lowlands. The term is also used for the area north and west of theHighland Boundary Fault,although the exact boundaries are not clearly defined, particularly to the east. TheGreat Glendivides theGrampian Mountainsto the southeast from theNorthwest Highlands.TheScottish Gaelicname ofA' Ghàidhealtachdliterally means "the place of the Gaels" and traditionally, from a Gaelic-speaking point of view, includes both theWestern Islesand the Highlands.

The area is very sparsely populated, with manymountain rangesdominating the region, and includes the highest mountain in theBritish Isles,Ben Nevis.During the 18th and early 19th centuries the population of the Highlands rose to around 300,000, but from c. 1841 and for the next 160 years, the natural increase in population was exceeded by emigration (mostly to Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand, and migration to the industrial cities of Scotland and England.)[2]: xxiii, 414 andpassim The area is now one of the most sparsely populated in Europe. At 9.1/km2(24/sq mi) in 2012,[3]the population density in the Highlands and Islands is less than one seventh of Scotland's as a whole.[3]

TheHighland Councilis the administrative body for much of the Highlands, with its administrative centre atInverness.However, the Highlands also includes parts of thecouncil areasofAberdeenshire,Angus,Argyll and Bute,Moray,North Ayrshire,Perth and Kinross,StirlingandWest Dunbartonshire.

The Scottish Highlands is the only area in the British Isles to have thetaigabiome as it features concentrated populations ofScots pineforest:[4]seeCaledonian Forest.It is the most mountainous part of theUnited Kingdom.

History

[edit]Culture

[edit]

Between the 15th century and the mid-20th century, the area differed from most of theLowlandsin terms of language. In Scottish Gaelic, the region is known as theGàidhealtachd,[5]because it was traditionally the Gaelic-speaking part of Scotland, although the language is now largely confined toThe Hebrides.The terms are sometimes used interchangeably but have different meanings in their respective languages.Scottish English(in itsHighland form) is the predominant language of the area today, though Highland English has been influenced by Gaelic speech to a significant extent.[6]Historically, the "Highland line" distinguished the two Scottish cultures. While the Highland line broadly followed the geography of the Grampians in the south, it continued in the north, cutting off the north-eastern areas, that is EasternCaithness,Orkney andShetland,from the more Gaelic Highlands and Hebrides.[7][8]

Historically, the major social unit of the Highlands was theclan.Scottish kings, particularlyJames VI,saw clans as a challenge to their authority; the Highlands was seen by many as a lawless region. The Scots of the Lowlands viewed the Highlanders as backward and more "Irish". The Highlands were seen as the overspill of Gaelic Ireland. They made this distinction by separating Germanic "Scots" English and the Gaelic by renaming it "Erse" a play on Eire. Following theUnion of the Crowns,James VI had the military strength to back up any attempts to impose some control. The result was, in 1609, theStatutes of Ionawhich started the process of integrating clan leaders into Scottish society. The gradual changes continued into the 19th century, as clan chiefs thought of themselves less as patriarchal leaders of their people and more as commercial landlords. The first effect on the clansmen who were their tenants was the change to rents being payable in money rather than in kind. Later, rents were increased as Highland landowners sought to increase their income. This was followed, mostly in the period 1760–1850, byagricultural improvementthat often (particularly in the Western Highlands) involvedclearanceof the population to make way for large scale sheep farms. Displaced tenants were set up incroftingcommunities in the process. The crofts were intended not to provide all the needs of their occupiers; they were expected to work in other industries such as kelping and fishing. Crofters came to rely substantially on seasonal migrant work, particularly in the Lowlands. This gave impetus to the learning of English, which was seen by many rural Gaelic speakers to be the essential "language of work".[9]: 105–07 [10]: 1–17, 110–18 [11]: 37–46, 65–73, 132

Older historiography attributes the collapse of the clan system to the aftermath of theJacobiterisings. This is now thought less influential by historians. Following theJacobite rising of 1745the British government enacted a series of laws to try to suppress theclan system,includingbans on the bearing of armsand the wearing oftartan,and limitations on the activities of theScottish Episcopal Church.Most of this legislation was repealed by the end of the 18th century as the Jacobite threat subsided. There was soon a rehabilitation of Highland culture. Tartan was adopted for Highland regiments in the British Army, which poor Highlanders joined in large numbers in the era of the Revolutionary andNapoleonic Wars(1790–1815). Tartan had largely been abandoned by the ordinary people of the region, but in the 1820s, tartan and thekiltwere adopted by members of the social elite, not just in Scotland, but across Europe.[12][13]The international craze for tartan, and for idealising a romanticised Highlands, was set off by theOssiancycle,[14][15]and further popularised by the works ofWalter Scott.His "staging" of thevisit of King George IV to Scotlandin 1822 and the king's wearing of tartan resulted in a massive upsurge in demand for kilts and tartans that could not be met by the Scottish woollen industry. Individual clan tartans were largely designated in this period and they became a major symbol of Scottish identity.[16]This "Highlandism", by which all of Scotland was identified with the culture of the Highlands, was cemented by Queen Victoria's interest in the country, her adoption ofBalmoralas a major royal retreat, and her interest in "tartenry".[13]

Economy

[edit]Recurrent famine affected the Highlands for much of its history, with significant instances as late as 1817 in the Eastern Highlands and the early 1850s in the West.[2]: 415–16 Over the 18th century, the region had developed a trade of black cattle into Lowland markets, and this was balanced by imports ofmealinto the area. There was a critical reliance on this trade to provide sufficient food, and it is seen as an essential prerequisite for the population growth that started in the 18th century.[2]: 48–49 Most of the Highlands, particularly in the North and West was short of the arable land that was essential for the mixed,run rigbased, communal farming that existed beforeagricultural improvementwas introduced into the region.[a]Between the 1760s and the 1830s there was a substantial trade in unlicensedwhiskythat had been distilled in the Highlands. Lowland distillers (who were not able to avoid the heavy taxation of this product) complained that Highland whisky made up more than half the market. The development of the cattle trade is taken as evidence that the pre-improvement Highlands was not an immutable system, but did exploit the economic opportunities that came its way.[11]: 24 The illicit whisky trade demonstrates the entrepreneurial ability of the peasant classes.[10]: 119–34

Agricultural improvement reached the Highlands mostly over the period 1760 to 1850. Agricultural advisors,factors,land surveyors and others educated in the thinking ofAdam Smithwere keen to put into practice the new ideas taught in Scottish universities.[11]: 141 Highland landowners, many of whom were burdened with chronic debts, were generally receptive to the advice they offered and keen to increase the income from their land.[17]: 417 In the East and South the resulting change was similar to that in the Lowlands, with the creation of larger farms with single tenants,enclosureof the old run rig fields, introduction of new crops (such asturnips), land drainage and, as a consequence of all this, eviction, as part of theHighland clearances,of many tenants and cottars. Some of those cleared found employment on the new, larger farms, others moved to the accessible towns of the Lowlands.[18]: 1–12

In the West and North, evicted tenants were usually given tenancies in newly createdcroftingcommunities, while their former holdings were converted into large sheep farms. Sheep farmers could pay substantially higher rents than the run rig farmers and were much less prone to falling into arrears. Each croft was limited in size so that the tenants would have to find work elsewhere. The major alternatives were fishing and the kelp industry. Landlords took control of the kelp shores, deducting the wages earned by their tenants from the rent due and retaining the large profits that could be earned at the high prices paid for the processed product during the Napoleonic wars.[18]: 1–12

When the Napoleonic wars finished in 1815, the Highland industries were affected by the return to a peacetime economy. The price of black cattle fell, nearly halving between 1810 and the 1830s. Kelp prices had peaked in 1810, but reduced from £9 a ton in 1823 to £3 13s 4d a ton in 1828. Wool prices were also badly affected.[19]: 370–71 This worsened the financial problems of debt-encumbered landlords. Then, in 1846,potato blightarrived in the Highlands, wiping out the essential subsistence crop for the overcrowded crofting communities. As thefaminestruck, the government made clear to landlords that it was their responsibility to provide famine relief for their tenants. The result of the economic downturn had been that a large proportion of Highland estates were sold in the first half of the 19th century.T M Devinepoints out that in the region most affected by the potato famine, by 1846, 70 per cent of the landowners were new purchasers who had not owned Highland property before 1800. More landlords were obliged to sell due to the cost of famine relief. Those who were protected from the worst of the crisis were those with extensive rental income from sheep farms.[18]: 93–95 Government loans were made available for drainage works, road building and other improvements and many crofters became temporary migrants – taking work in the Lowlands. When the potato famine ceased in 1856, this established a pattern of more extensive working away from the Highlands.[18]: 146–66

The unequalconcentration of land ownershipremained an emotional and controversial subject, of enormous importance to the Highland economy, and eventually became a cornerstone of liberal radicalism. The poor crofters were politically powerless, and many of them turned to religion. They embraced the popularly oriented, fervently evangelical Presbyterian revival after 1800.[20]Most joined the breakaway "Free Church" after 1843. Thisevangelicalmovement was led by lay preachers who themselves came from the lower strata, and whose preaching was implicitly critical of the established order. The religious change energised the crofters and separated them from the landlords; it helped prepare them for their successful and violent challenge to the landlords in the 1880s through theHighland Land League.[21] Violence erupted, starting on theIsle of Skye,when Highland landlords cleared their lands for sheep and deer parks. It was quietened when the government stepped in, passing theCrofters' Holdings (Scotland) Act, 1886to reduce rents, guarantee fixity of tenure, and break up large estates to provide crofts for the homeless.[22]This contrasted with theIrish Land Warunderway at the same time, where the Irish were intensely politicised through roots in Irish nationalism, while political dimensions were limited. In 1885 three Independent Crofter candidates were elected to Parliament, which listened to their pleas. The results included explicit security for the Scottish smallholders in the "crofting counties"; the legal right to bequeath tenancies to descendants; and the creation of a Crofting Commission. The Crofters as a political movement faded away by 1892, and theLiberal Partygained their votes.[23]

Whisky production

[edit]

Today, the Highlands are the largest of Scotland's whisky producing regions; the relevant area runs from Orkney to the Isle of Arran in the south and includes the northern isles and much of Inner and Outer Hebrides, Argyll, Stirlingshire, Arran, as well as sections of Perthshire and Aberdeenshire. (Other sources treat The Islands, exceptIslay,as a separate whisky producing region.) This massive area has over 30 distilleries, or 47 when the Islands sub-region is included in the count.[24]According to one source, the top five areMacallan,Glenfiddich,Aberlour,Glenfarclas,andBalvenie.While Speyside is geographically within the Highlands, that region is specified as distinct in terms of whisky productions.[25]Speyside single maltwhiskies are produced by about 50 distilleries.[25]

According toVisit Scotland,Highlands whisky is "fruity, sweet, spicy, malty".[26]Another review[25]states that Northern Highlands single malt is "sweet and full-bodied", the Eastern Highlands and Southern Highlands whiskies tend to be "lighter in texture" while the distilleries in the Western Highlands produce single malts with a "much peatier influence".

Religion

[edit]

TheScottish Reformationachieved partial success in the Highlands.Roman Catholicismremained strong in some areas, owing to remote locations and the efforts ofFranciscanmissionaries from Ireland, who regularly came to celebrateMass.There remain significant Catholic strongholds within the Highlands and Islands such asMoidartandMoraron the mainland andSouth UistandBarrain the southern Outer Hebrides. The remoteness of the region and the lack of a Gaelic-speaking clergy undermined the missionary efforts of the established church. The later 18th century saw somewhat greater success, owing to the efforts of theSSPCKmissionaries and to the disruption of traditional society after theBattle of Cullodenin 1746. In the 19th century, the evangelical Free Churches, which were more accepting of Gaelic language and culture, grew rapidly, appealing much more strongly than did the established church.[27]

For the most part, however, the Highlands are considered predominantly Protestant, belonging to theChurch of Scotland.In contrast to the Catholic southern islands, the northernOuter Hebridesislands (Lewis, Harris and North Uist) have an exceptionally high proportion of their population belonging to the ProtestantFree Church of Scotlandor theFree Presbyterian Church of Scotland.TheOuter Hebrideshave been described as the last bastion ofCalvinismin Britain[28]and the Sabbath remains widely observed. Inverness and the surrounding area has a majority Protestant population, with most locals belonging to eitherThe Kirkor theFree Church of Scotland.The church maintains a noticeable presence within the area, with church attendance notably higher than in other parts of Scotland. Religion continues to play an important role in Highland culture, with Sabbath observance still widely practised, particularly in the Hebrides.[29]

Historical geography

[edit]

In traditional Scottishgeography,the Highlands refers to that part of Scotland north-west of theHighland Boundary Fault,which crosses mainland Scotland in a near-straight line fromHelensburghtoStonehaven.However the flat coastal lands that occupy parts of the counties ofNairnshire,Morayshire,BanffshireandAberdeenshireare often excluded as they do not share the distinctive geographical and cultural features of the rest of the Highlands. The north-east ofCaithness,as well asOrkneyandShetland,are also often excluded from the Highlands, although theHebridesare usually included. The Highland area, as so defined, differed from theLowlandsin language and tradition, having preservedGaelicspeech and customs centuries after theanglicisationof the latter; this led to a growing perception of a divide, with the cultural distinction between Highlander and Lowlander first noted towards the end of the 14th century. InAberdeenshire,the boundary between the Highlands and the Lowlands is not well defined. There is a stone beside theA93 roadnear the village ofDinnetonRoyal Deesidewhich states 'You are now in the Highlands', although there are areas of Highland character to the east of this point.

A much wider definition of the Highlands is that used by theScotch whiskyindustry.Highland single maltsare produced at distilleries north of an imaginary line betweenDundeeandGreenock,[30]thus including all ofAberdeenshireandAngus.

Invernessis regarded as the Capital of the Highlands,[31]although less so in the Highland parts ofAberdeenshire,Angus,Perthshire andStirlingshirewhich look more toAberdeen,Dundee,Perth,andStirlingas their commercial centres.[32]

Highland Council area

[edit]TheHighland Councilarea, created as one of the local governmentregions of Scotland,has been aunitary councilarea since 1996. The council area excludes a large area of the southern and eastern Highlands, and theWestern Isles,but includesCaithness.Highlandsis sometimes used, however, as a name for the council area, as in the formerHighlands and Islands Fire and Rescue Service.Northernis also used to refer to the area, as in the formerNorthern Constabulary.These former bodies both covered the Highland council area and theisland council areasofOrkney,Shetland and the Western Isles.

Highland Council signs in thePass of Drumochter,betweenGlen GarryandDalwhinnie,say "Welcome to the Highlands".

Highlands and Islands

[edit]

Much of the Highlands area overlaps theHighlands and Islandsarea. Anelectoral regioncalledHighlands and Islandsis used in elections to theScottish Parliament:this area includesOrkneyandShetland,as well as the Highland Council local government area, theWestern Islesand most of theArgyll and ButeandMoraylocal government areas.Highlands and Islandshas, however, different meanings in different contexts. It means Highland (the local government area), Orkney, Shetland, and the Western Isles inHighlands and Islands Fire and Rescue Service.Northern,as inNorthern Constabulary,refers to the same area as that covered by the fire and rescue service.

Historical crossings

[edit]There have beentrackwaysfrom the Lowlands to the Highlands sinceprehistorictimes. Many traverse theMounth,a spur of mountainous land that extends from the higher inland range to theNorth Seaslightly north ofStonehaven.The most well-known and historically important trackways are theCausey Mounth,Elsick Mounth,[33]Cryne Corse MounthandCairnamounth.[34]

Courier delivery

[edit]Although most of the Highlands is geographically on the British mainland, it is somewhat less accessible than the rest of Britain; thus most UK couriers categorise it separately, alongsideNorthern Ireland,theIsle of Man,and other offshore islands. They thus charge additional fees for delivery to the Highlands, or exclude the area entirely. While the physical remoteness from the largest population centres inevitably leads to higher transit cost, there is confusion and consternation over the scale of the fees charged and the effectiveness of their communication,[35]and the use of the word Mainland in their justification. Since the charges are often based on postcode areas, many far less remote areas, including some which are traditionally considered part of the lowlands, are also subject to these charges.[35]Royal Mailis the only delivery network bound by a Universal Service Obligation to charge a uniform tariff across the UK. This, however, applies only to mail items and not larger packages which are dealt with by itsParcelforcedivision.

Geology

[edit]

The Highlands lie to the north and west of theHighland Boundary Fault,which runs fromArrantoStonehaven.This part of Scotland is largely composed of ancient rocks from theCambrianandPrecambrianperiods which wereupliftedduring the laterCaledonian Orogeny.Smaller formations ofLewisian gneissin the northwest are up to 3 billion years old. The overlying rocks of theTorridon Sandstoneform mountains in theTorridon Hillssuch asLiathachandBeinn EigheinWester Ross.

These foundations are interspersed with manyigneousintrusions of a more recent age, the remnants of which have formed mountainmassifssuch as theCairngormsand theCuillinofSkye.A significant exception to the above are the fossil-bearing beds ofOld Red Sandstonefound principally along theMoray Firthcoast and partially down the Highland Boundary Fault. TheJurassicbeds found in isolated locations onSkyeandApplecrossreflect the complex underlying geology. They are the original source of muchNorth Sea oil.TheGreat Glenis formed along atransform faultwhich divides theGrampian Mountainsto the southeast from theNorthwest Highlands.[36][37]

The entire region was covered by ice sheets during thePleistoceneice ages, save perhaps for a fewnunataks.The complexgeomorphologyincludes incised valleys andlochscarved by the action of mountain streams and ice, and atopographyof irregularly distributed mountains whose summits have similar heights above sea-level, but whose bases depend upon the amount ofdenudationto which the plateau has been subjected in various places.[38]

Climate

[edit]The region is much warmer than other areas at similar latitudes (such asKamchatkainRussia,orLabradorinCanada) because of theGulf Streammaking it cool, damp and temperate. TheKöppen climate classificationis "Cfb"at low elevations, then becoming"Cfc","Dfc"and"ET"at higher elevations.

Places of interest

[edit]- An Teallach

- Aonach Mòr(Nevis Range ski centre)

- Arrochar Alps

- Balmoral Castle

- Balquhidder

- Battlefield of Culloden

- Beinn Alligin

- Beinn Eighe

- Ben Cruachan hydro-electric power station

- Ben Lomond

- Ben Macdui(second highest mountain in Scotland and UK)

- Ben Nevis(highest mountain in Scotland and UK)

- Cairngorms National Park

- Cairngorm Ski centrenearAviemore

- Cairngorm Mountains

- Caledonian Canal

- Cape Wrath

- Carrick Castle

- Castle Stalker

- Castle Tioram

- Chanonry Point

- Conic Hill

- Culloden Moor

- Dunadd

- Duart Castle

- Durness

- Eilean Donan

- Fingal's Cave(Staffa)

- Fort George

- Glen Coe

- Glen Etive

- Glen Kinglas

- Glen Lyon

- Glen Orchy

- Glenshee Ski Centre

- Glen Shiel

- Glen Spean

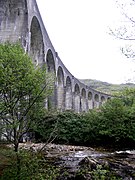

- Glenfinnan(and itsrailway stationandviaduct)

- Grampian Mountains

- Hebrides

- Highland Folk Museum– The first open-air museum in the UK.

- Highland Wildlife Park

- Inveraray Castle

- Inveraray Jail

- Inverness Castle

- Inverewe Garden

- Iona Abbey

- Isle of Staffa

- Kilchurn Castle

- Kilmartin Glen

- Liathach

- Lecht Ski Centre

- Loch Alsh

- Loch Ard

- Loch Awe

- Loch Assynt

- Loch Earn

- Loch Etive

- Loch Fyne

- Loch Goil

- Loch Katrine

- Loch Leven

- Loch Linnhe

- Loch Lochy

- Loch Lomond

- Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park

- Loch Lubnaig

- Loch Maree

- Loch Morar

- Loch Morlich

- Loch Ness

- Loch Nevis

- Loch Rannoch

- Loch Tay

- Lochranza

- Luss

- Meall a' Bhuiridh(Glencoe Ski Centre)

- ScottishSea Life SanctuaryatLoch Creran

- Rannoch Moor

- Red Cuillin

- Rest and Be Thankfulstretch of A83

- River Carron, Wester Ross

- River Spey

- River Tay

- Ross and Cromarty

- Smoo Cave

- Stob Coire a' Chàirn

- Stac Polly

- Strathspey Railway

- Sutherland

- Tor Castle

- Torridon Hills

- Urquhart Castle

- West Highland Line(scenic railway)

- West Highland Way(Long-distance footpath)

- Wester Ross

Gallery

[edit]-

TheGlenfinnan Viaductfrom below.

-

Loch Scavaig,Isle of Skye

-

The islands ofLoch Maree

-

The interior ofSmoo Cave,Sutherland

-

Cape WrathLighthouse in the far NW of the Highlands

-

The Kyle ofDurness

-

Two hinds in the Highlands

-

Loch an Lòin

-

Highland Cattleoriginates from the Scottish Highlands

See also

[edit]- Ben Nevis

- Buachaille Etive Mòr

- The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black OilbyJohn McGrath

- Fauna of Scotland

- Highland 2007

- James Hunter (historian),historian who wrote several books related to the Scottish Highlands

- List of fauna of the Scottish Highlands

- List of towns and villages in the Scottish Highlands

- Mountains and hills of Scotland

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^"Highlands | region, Scotland, United Kingdom".Encyclopædia Britannica.Retrieved10 May2017.

- ^abcRichards, Eric (2000).The Highland Clearances People, Landlords and Rural Turmoil(2013 ed.). Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited.ISBN978-1-78027-165-1.

- ^ab"Highland profile – key facts and figures".The Highland Council.Retrieved2 June2014.

- ^"Taiga | Plants, Animals, Climate, Location, & Facts | Britannica".www.britannica.com.Retrieved4 May2023.

- ^Martin Ball; James Fife (1993).The Celtic Languages.Routledge. p. 136.ISBN978-0-415-01035-1.

- ^Charles Jones (1997).The Edinburgh History of the Scots Language.Edinburgh University Press. pp. 566–67.ISBN978-0-7486-0754-9.

- ^"The Highland Line".Sue & Marilyn. Archived fromthe originalon 8 August 2017.Retrieved8 March2013.

- ^"Historical Geography of the Clans of Scotland".Electricscotland.com.Retrieved8 March2013.

- ^Dodgshon, Robert A. (1998).From Chiefs to Landlords: Social and Economic Change in the Western Highlands and Islands, c. 1493–1820.Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.ISBN0-7486-1034-0.

- ^abDevine, T M (1994).Clanship to Crofters' War: The social transformation of the Scottish Highlands(2013 ed.). Manchester University Press.ISBN978-0-7190-9076-9.

- ^abcdDevine, T M (2018).The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed, 1600–1900.London: Allen Lane.ISBN978-0-241-30410-5.

- ^John Lenox Roberts (2002).The Jacobite Wars: Scotland and the Military Campaigns of 1715 and 1745.Polygon at Edinburgh. pp.193–95.ISBN978-1-902930-29-9.

- ^abMarco Sievers (2007).The Highland Myth as an Invented Tradition of 18th and 19th Century and Its Significance for the Image of Scotland.GRIN Verlag. pp. 22–25.ISBN978-3-638-81651-9.

- ^Deidre Dawson; Pierre Morère (2004).Scotland and France in the Enlightenment.Bucknell University Press. pp. 75–76.ISBN978-0-8387-5526-6.

- ^William Ferguson (1998).The Identity of the Scottish Nation: An Historic Quest.Edinburgh University Press. p. 227.ISBN978-0-7486-1071-6.

- ^Norman C Milne (2010).Scottish Culture and Traditions.Paragon Publishing. p. 138.ISBN978-1-899820-79-5.

- ^Richards, Eric (1985).A History of the Highland Clearances, Volume 2: Emigration, Protest, Reasons.Beckenham, Kent and Sydney, Australia: Croom Helm Ltd.ISBN978-0-7099-2259-9.

- ^abcdDevine, T M (1995).The Great Highland Famine: Hunger, Emigration and the Scottish Highlands in the Nineteenth Century.Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited.ISBN1-904607-42-X.

- ^Lynch, Michael (1991).Scotland, a New History(1992 ed.). London: Pimlico.ISBN978-0-7126-9893-1.

- ^Thomas Martin Devine (1999). "Chapter 18".The Scottish Nation.Penguin Books.ISBN978-0-670-88811-5.

- ^James Hunter (1974). "The Emergence of the Crofting Community: The Religious Contribution 1798–1843".Scottish Studies.18:95–116.

- ^Ian Bradley (December 1987)."'Having and Holding' – The Highland Land War of the 1880s ".History Today.37(12): 23–28.Retrieved8 March2013.

- ^Ewen A. Cameron (June 2005). "Communication or Separation? Reactions to Irish Land Agitation and Legislation in the Highlands of Scotland, c. 1870–1910".English Historical Review.120(487): 633–66.doi:10.1093/ehr/cei124.

- ^"Highland Distilleries – Whisky Tours, Tastings & Map".www.visitscotland.com.

- ^abcOsborn, Jacob (13 August 2019)."A Comprehensive Guide to Scotland's Whisky Regions".Man of Many.

- ^"Whisky Distilleries in the Highlands".VisitScotland.Retrieved25 August2021.

- ^George Robb (1990). "Popular Religion and the Christianisation of the Highlands in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries".Journal of Religious History.16(1): 18–34.doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.1990.tb00647.x.

- ^Gerard Seenan (10 April 2006)."Fury at ferry crossing on Sabbath".The Guardian.Retrieved8 March2013.

- ^Cook, James (29 March 2011)."Battle looms in Outer Hebrides over Sabbath opening".BBC News.Retrieved3 June2014.

- ^"Whisky Regions & Tours".Scotch Whisky Association. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2018.Retrieved8 March2013.

- ^"Inverness: Capital of the Scottish Highlands".Internet Guide to Scotland.Retrieved8 March2013.

- ^"Scottish Highlands Landscape and History – Scotland Info Guide".www.scotlandinfo.eu.

- ^C Michael Hogan (22 November 2007)."Elsick Mounth – Ancient Trackway in Scotland in Aberdeenshire".The Megalithic Portal.Retrieved8 March2013.

- ^W. Douglas Simpson (10 December 1928)."The Early Castles of Mar"(PDF).Proceedings of the Society.Retrieved8 March2013.[dead link]

- ^ab"3,000 angry Scots respond to CAB survey on rural delivery charges".2012The Scottish Association of Citizens Advice Bureaux– Citizens Advice Scotland (Scottish charity SC016637). 25 January 2012.Retrieved31 July2013.

- ^John Keay, Julia Keay (1994).Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland.HarperCollins.ISBN978-0-00-710353-9.

- ^William Hutchison Murray (1973).The islands of Western Scotland: the Inner and Outer Hebrides.Eyre Methuen.

- ^One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911). "Highlands, The".Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 455–456.

Further reading

[edit]- Baxter, Colin, and C. J. Tabraham.The Scottish Highlands(2008), heavily illustrated

- Gray, Malcolm.The Highland Economy, 1750–1850(Edinburgh, 1957)

- Humphreys, Rob, and Donald Reid.The Rough Guide to Scottish Highlands and Islands(3rd ed. 2004)

- Keay, J. and J. Keay.Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland(1994)

- Kermack, William Ramsay.The Scottish Highlands: a short history, c. 300–1746(1957)

- Lister, John Anthony.The Scottish Highlands(1978)

External links

[edit]- Am Baile – Highland History & Culture in English and Gaelic

- WalkHighland– walking guide

- National Library of Scotland: SCOTTISH SCREEN ARCHIVE(selection of archive films relating to the Scottish Highlands)