Toxoplasma gondii

| Toxoplasma gondii | |

|---|---|

| |

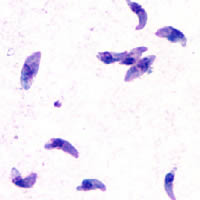

| GiemsastainedT. gondiitachyzoites,1000× magnification | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Clade: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Apicomplexa |

| Class: | Conoidasida |

| Order: | Eucoccidiorida |

| Family: | Sarcocystidae |

| Subfamily: | Toxoplasmatinae |

| Genus: | Toxoplasma Nicolle&Manceaux,1909[2] |

| Species: | T. gondii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Toxoplasma gondii (Nicolle & Manceaux, 1908)[1]

| |

Toxoplasma gondii(/ˈtɒksəˌplæzməˈɡɒndi.aɪ,-iː/) is a parasiticprotozoan(specifically anapicomplexan) that causestoxoplasmosis.[3]Found worldwide,T. gondiiis capable of infecting virtually allwarm-bloodedanimals,[4]: 1 butfelidsare the only knowndefinitive hostsin which the parasite may undergo sexual reproduction.[5][6]

Inrodents,T. gondiialters behaviorin ways that increase the rodents' chances of beingpreyedupon by felids.[7][8][9]Support for this "manipulation hypothesis" stems from studies showing thatT. gondii-infected rats have a decreased aversion to caturinewhile infection inmicelowers generalanxiety,increases explorativebehaviorsand increases a loss of aversion to predators in general.[7][10]Because cats are one of the only hosts within whichT. gondiican sexually reproduce, such behavioral manipulations are thought to beevolutionary adaptationsthat increase the parasite'sreproductive successsince rodents that do not avoid cat habitations will more likely become cat prey.[7]The primary mechanisms ofT. gondii–induced behavioral changes in rodents occur throughepigenetic remodelingin neurons that govern the relevant behaviors (e.g.hypomethylationofarginine vasopressin-related genes in the medialamygdala,which greatly decrease predator aversion).[11][12]

In humans, particularly infants and those withweakened immunity,T. gondiiinfection is generally asymptomatic but may lead to a serious case oftoxoplasmosis.[13][4]T. gondiican initially cause mild, flu-like symptoms in the first few weeks following exposure, but otherwise, healthy human adults are asymptomatic.[14][13][4]This asymptomatic state of infection is referred to as alatent infection,and it has been associated with numerous subtle behavioral, psychiatric, and personality alterations in humans.[14][15][16]Behavioral changes observed between infected and non-infected humans include a decreased aversion to cat urine (but with divergent trajectories by gender) and an increased risk ofschizophrenia.[17]Preliminary evidence has suggested thatT. gondiiinfection may induce some of the same alterations in thehuman brainas those observed in rodents.[18][19][9][20][21][22]Many of these associations have been strongly debated and newer studies have found them to be weak, concluding:[23]

On the whole, there was little evidence thatT.gondiiwas related to increased risk of psychiatric disorder, poor impulse control, personality aberrations, or neurocognitive impairment.

However, there is evidence thatT. Gondiimay cause suicidal ideation and suicide, in humans[24]

T. gondiiis one of the most common parasites in developed countries;[25][26]serologicalstudies estimate that up to 50% of the global population has been exposed to, and may be chronically infected with,T. gondii;although infection rates differ significantly from country to country.[14][27]Estimates have shown the highest IgG seroprevalence to be inEthiopia,at 64.2%, as of 2018.[28]

Structure

[edit]

T. gondiicontains organelles calledrhoptriesandmicronemes,as well as other organelles.

Life cycle

[edit]

Thelife cycleofT. gondiimay be broadly summarized into two components: a sexual component that occurs only within cats (felids, wild or domestic), and an asexual component that can occur within virtually all warm-blooded animals, including humans, cats, and birds.[29]: 2 BecauseT. gondiican sexually reproduce only within cats, cats are therefore the definitive host ofT. gondii.All other hosts – in which only asexual reproduction can occur – areintermediate hosts.

Sexual reproduction in the feline definitive host

[edit]When a feline is infected withT. gondii(e.g. by consuming an infected mouse carrying the parasite's tissue cysts), the parasite survives passage through thestomach,eventually infectingepithelial cellsof the cat's small intestine.[29]: 39 Inside these intestinal cells, the parasites undergo sexual development and reproduction, producing millions of thick-walled,zygote-containing cysts known as oocysts. Felines are the only definitive host because they lack expression of the enzymedelta-6-desaturase(D6D) in their intestine. This enzyme convertslinoleic acid;the absence of expression allows systemic linoleic acid accumulation. Recent findings showed that this excess of linoleic acid is essential forT. gondiisexual reproduction.[6]

Feline shedding of oocysts

[edit]Infected epithelial cells eventually rupture and release oocysts into theintestinal lumen,whereupon they are shed in the cat's feces.[4]: 22 Oocysts can then spread to soil, water, food, or anything potentially contaminated with the feces. Highly resilient, oocysts can survive and remain infective for many months in cold and dry climates.[30]

Ingestion of oocysts by humans or other warm-blooded animals is one of the common routes of infection.[31]Humans can be exposed to oocysts by, for example, consuming unwashed vegetables or contaminated water, or by handling the feces (litter) of an infected cat.[29]: 2 [32]Although cats can also be infected by ingesting oocysts, they are much less sensitive to oocyst infection than are intermediate hosts.[33][4]: 107

Initial infection of the intermediate host

[edit]Intermediate hostsfound include pigs, chickens, goats, sheep[29]: 2 andMacropus rufusby Moré et al. 2010.[34]: 162 Cattleandhorsesareresistantand thought to be incapable of significant infection.[29]: 11 T. gondiiis considered to have three stages of infection; the tachyzoite stage of rapid division, the bradyzoite stage of slow division within tissue cysts, and the oocyst environmental stage.[35]Tachyzoites are also known as "tachyzoic merozoites" and bradyzoites as "bradyzoic merozoites".[36]When an oocyst or tissue cyst is ingested by a human or other warm-blooded animal, the resilient cyst wall is dissolved byproteolytic enzymesin the stomach and small intestine, freeing sporozoites from within the oocyst.[31][35]The parasites first invade cells in and surrounding the intestinal epithelium, and inside these cells, the parasites differentiate into tachyzoites, the motile and quickly multiplying cellular stage ofT. gondii.[29]: 39 Tissue cysts in tissues such as brain and muscle tissue, form about 7–10 days after initial infection.[35]Although severe infection ofM. rufushas been observed it is unknown whether this is common.[34]

Asexual reproduction in the intermediate host

[edit]Inside host cells, thetachyzoitesreplicate inside specializedvacuoles(called theparasitophorous vacuoles) created from host cell membrane during invasion into the cell.[29]: 23–39 Tachyzoites multiply inside this vacuole until the host cell dies and ruptures, releasing and spreading the tachyzoites via the bloodstream to allorgansand tissues of the body, including thebrain.[29]: 39–40

Growth in tissue culture

[edit]The parasite can be easily grown in monolayers of mammalian cells maintained in vitro intissue culture.It readily invades and multiplies in a wide variety offibroblastandmonocytecell lines.In infected cultures, the parasite rapidly multiplies and thousands of tachyzoites break out of infected cells and enter adjacent cells, destroying the monolayer in due course. New monolayers can then be infected using a drop of this infected culture fluid and the parasite indefinitely maintained without the need of animals.

Formation of tissue cysts

[edit]Following the initial period of infection characterized by tachyzoite proliferation throughout the body, pressure from the host'simmune systemcausesT. gondiitachyzoites to convert into bradyzoites, the semidormant,slowlydividingcellular stage of the parasite.[37]Inside host cells, clusters of these bradyzoites are known as tissue cysts. The cyst wall is formed by the parasitophorous vacuole membrane.[29]: 343 Although bradyzoite-containing tissue cysts can form in virtually any organ, tissue cysts predominantly form and persist in the brain, theeyes,andstriated muscle(including the heart).[29]: 343 However, specific tissue tropisms can vary between intermediate host species; in pigs, the majority of tissue cysts are found in muscle tissue, whereas in mice, the majority of cysts are found in the brain.[29]: 41

Cysts usually range in size between five and 50μmin diameter,[38](with 50 μm being about two-thirds the width of the average human hair).[39]

Consumption of tissue cysts in meat is one of the primary means ofT. gondiiinfection, both for humans and for meat-eating, warm-blooded animals.[29]: 3 Humans consume tissue cysts when eating raw or undercooked meat (particularly pork and lamb).[40]Tissue cyst consumption is also the primary means by which cats are infected.[4]: 46

An exhibit at theSan Diego Natural History Museumstatesurban runoffwith cat feces transportsToxoplasma gondiiinto the ocean, which can kill sea otters.[41]

Chronic infection

[edit]Tissue cysts can be maintained in host tissue for the lifetime of the animal.[29]: 580 However, the perpetual presence of cysts appears to be due to a periodic process of cyst rupturing and re-encysting, rather than a perpetual lifespan of individual cysts or bradyzoites.[29]: 580 At any given time in a chronically infected host, a very small percentage of cysts are rupturing,[29]: 45 although the exact cause of this tissue cyst rupture is, as of 2010, not yet known.[4]: 47

Theoretically,T. gondiican be passed between intermediate hosts indefinitely via a cycle of consumption of tissue cysts in meat. However, the parasite's life cycle begins and completes only when the parasite is passed to a feline host, the only host within which the parasite can again undergo sexual development and reproduction.[31]

Population structure in the wild

[edit]In 2006, researchers reviewed evidence thatT. gondiihas an unusual population structure dominated by three clonal lineages called Types I, II and III that occur in North America and Europe, despite the occurrence of a sexual phase in its life cycle. They estimated that a common ancestor existed about 10,000 years ago.[42]Authors of a subsequent and larger study on 196 isolates from diverse sources includingT. gondiiin the bald eagle, gray wolf, Arctic fox and sea otter, also found thatT. gondiistrains infecting North American wildlife have limited genetic diversity with the occurrence of only a few major clonal types. They found that 85% of strains in North America were of one of three widespread genotypes II, III and Type 12. ThusT. gondiihas retained the capability for sex in North America over many generations, producing largely clonal populations, and matings have generated little genetic diversity.[43]

Cellular stages

[edit]During different periods of its life cycle, individual parasites convert into various cellular stages, with each stage characterized by a distinct cellularmorphology,biochemistry,and behavior. These stages include the tachyzoites, merozoites, bradyzoites (found in tissue cysts), and sporozoites (found in oocysts).

Some stages aremotileand somecalcium-dependent protein kinases(TgCDPKs) are involved in this parasite's motility.[44][45]Gaji et al. 2015 findTgCDPK3is required to begin the action of motility because itphosphorylatesT. gondii'smyosinA(TgMYOA).[44][45]TgCDPK3 is the functional orthologue ofCDPK1in this parasite.[45]

Tachyzoites

[edit]

Motile,and quickly multiplying, tachyzoites are responsible for expanding the population of the parasite in the host.[46][29]: 19 When a host consumes a tissue cyst (containing bradyzoites) or an oocyst (containing sporozoites), the bradyzoites or sporozoites stage-convert into tachyzoites upon infecting the intestinal epithelium of the host.[29]: 359 During the initial acute period of infection, tachyzoites spread throughout the body via the blood stream.[29]: 39–40 During the later, latent (chronic) stages of infection, tachyzoites stage-convert to bradyzoites to form tissue cysts.

Merozoites

[edit]

Like tachyzoites, merozoites divide quickly and are responsible for expanding the population of the parasite inside the cat's intestine before sexual reproduction.[29]When a feline definitive host consumes a tissue cyst (containing bradyzoites), bradyzoites convert into merozoites inside intestinal epithelial cells. Following a brief period of rapid population growth in the intestinal epithelium, merozoites convert into the noninfectious sexual stages of the parasite to undergo sexual reproduction, eventually resulting in zygote-containing oocysts.[29]: 306

Studying the sexual phases of theT. gondiilife cycle remains challenging and determining the precise triggers and molecular mechanisms governing this developmental program remains an ongoing area of research. Major challenges associated with the ability to cultivate presexual and sexual stages ofT. gondiiin vitrohave limited our understanding of this developmental program and how it is triggered by the parasite in response to the infection of the cat. Multiple studies[47],[48]revealed distinct differences in thetranscriptomesof the asexual and sexual stages ofT. gondii.Additionally, metabolic disparities within the feline host have been identified as key factors influencing the transition to sexual stages.[49]However, linking gene expression patterns to stage transitions and deciphering the genetic triggers driving the switch from asexual to sexual development remain unresolved.

Important recent advancements in the field have shed new light on the regulatory mechanisms governing sexual development inT. gondii.Farhat and colleagues[50]showed that chromatin modifiers MORC and HDAC3 play critical roles in silencing sexual development-specific genes. In MORC-depleted parasites, a broad activation of sexual gene expression was observed. In a later study, it was suggested that MORC-depleted parasites have disrupted sub-telomeric gene silencing. The disorganization in telomeres may have led to the misregulation of sexual development.

Moreover, the discovery of specific transcription factors essential for sexual commitment has provided invaluable insights into the intricate regulatory network orchestrating stage specificity inT. gondii.Multiple parasite transcription factors have been identified as critical suppressors of presexual development,[51]permitting the study of presexual stages and opening new avenues for using genetics to drive the full sexual cyclein vitro.Specifically, the depletion of AP2XI-2 and AP2XII-1 inT. gondiiinduces merozoite-specific gene expression, raising the possibility for cultivatingT. gondiisexual development in laboratory settings.

Crucial questions still persist regarding the genetic determinants that dictate whether parasites develop into macrogametes or microgametes. The development of new molecular and genomic approaches, such as single-cell transcriptomics andproteomics,should be useful to those in the field working towards unraveling the molecular intricacies of this process.

Bradyzoites

[edit]Bradyzoites are the slowly dividing stage of the parasite that make up tissue cysts. When an uninfected host consumes a tissue cyst, bradyzoites released from the cyst infect intestinal epithelial cells before converting to the proliferative tachyzoite stage.[29]: 359 Following the initial period of proliferation throughout the host body, tachyzoites then convert back to bradyzoites, which reproduce inside host cells to form tissue cysts in the new host.

Sporozoites

[edit]Sporozoites are the stage of the parasite residing within oocysts. When a human or other warm-blooded host consumes an oocyst, sporozoites are released from it, infecting epithelial cells before converting to the proliferative tachyzoite stage.[29]: 359

Immune response

[edit]Initially, aT. gondiiinfection stimulates production of IL-2 and IFN-γ by the innate immune system.[37]Continuous IFN-γ production is necessary for control of both acute and chronicT. gondiiinfection.[37]These two cytokines elicit a CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell mediated immune response.[37]Thus, T-cells play a central role in immunity againstToxoplasmainfection. T-cells recognizeToxoplasmaantigens that are presented to them by the body's own Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules. The specific genetic sequence of a given MHC molecule differs dramatically between individuals, which is why these molecules are involved in transplant rejection. Individuals carrying certain genetic sequences of MHC molecules are much more likely to be infected withToxoplasma.One study of >1600 individuals found that Toxoplasma infection was especially common among people who expressed certain MHC alleles (HLA-B*08:01, HLA-C*04:01, HLA-DRB 03:01, HLA-DQA*05:01 and HLA-DQB*02:01).[52]

IL-12 is produced duringT. gondiiinfection to activatenatural killer (NK) cells.[37]Tryptophanis an essential amino acid forT. gondii,which it scavenges from host cells. IFN-γ induces the activation ofindole-amine-2,3-dioxygenase(IDO) andtryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase(TDO), two enzymes that are responsible for the degradation of tryptophan.[53]Immune pressure eventually leads the parasite to form cysts that normally are deposited in the muscles and in the brain of the hosts.[37]

Immune response and behavior alterations

[edit]The IFN-γ-mediated activation of IDO and TDO is an evolutionary mechanism that serves to starve the parasite, but it can result in depletion of tryptophan in the brain of the host. IDO and TDO degrade tryptophan toN-formylkynurenine.Administration of L-kynurenine is capable of inducing depressive-like behavior in mice.[53]T. gondiiinfection has been demonstrated to increase the levels ofkynurenic acid(KYNA) in the brains of infected mice and in the brain of schizophrenic persons.[53]Low levels of tryptophan andserotoninin the brain were already associated with depression.[54]

Risk factors for human infection

[edit]The following have been identified as beingrisk factorsforT. gondiiinfection in humans and warm-blooded animals:

- by consuming raw or undercooked meat containingT. gondiitissue cysts.[32][55][56][57][58]The most common threat to citizens in theUnited Statesis from eating raw or undercooked pork.[59]

- by ingesting water, soil, vegetables, or anything contaminated withoocystsshed in thefecesof an infected animal.[55]Cat fecal matter is particularly dangerous: Just one cyst consumed by a cat can result in thousands of oocysts. This is why physicians recommend pregnant or ill persons do not clean the cat's litter box at home.[59]These oocysts are resilient to harsh environmental conditions and can survive over a year in contaminated soil.[35][60]

- from ablood transfusionororgan transplant[61]

- fromtransplacental transmissionfrom mother to fetus, particularly whenT. gondiiis contracted duringpregnancy[55]

- from drinkingunpasteurizedgoat milk[56]

- from raw and treated sewage and bivalve shellfish contaminated by treated sewage[62][63][64][65]

A common argument in the debate about whether cat ownership is ethical involves the question ofT. gondiitransmission to humans.[66]Even though "living in a household with a cat that used alitter boxwas strongly associated with infection, "[32]and that living with several kittens or any cat under one year of age has some significance,[56]several other studies claim to have shown that living in a household with a cat is not a significant risk factor forT. gondiiinfection.[57][67]

Specific vectors for transmission may also differ based on geographic location. "The seawater in California is thought to be contaminated byT. gondiioocysts that originate from cat feces, survive or bypass sewage treatment, and travel to the coast through river systems.T. gondiihas been identified in a California mussel by polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing. In light of the potential presence ofT. gondii,pregnant women and immunosuppressed persons should be aware of this potential risk associated with eating raw oysters, mussels, and clams. "[56]

In warm-blooded animals, such asbrown rats,sheep, and dogs,T. gondiihas also been shown to be sexually transmitted.[68][69][70]AlthoughT. gondiican infect, be transmitted by, andasexually reproducewithin humans and virtually all other warm-blooded animals, the parasite cansexually reproduceonly within theintestinesof members of thecat family (felids).[31]Felids are therefore thedefinitive hostsofT. gondii;all other hosts (such as human or other mammals) areintermediate hosts.

Preventing infection

[edit]The following precautions are recommended to prevent or greatly reduce the chances of becoming infected withT. gondii.This information has been adapted from the websites of United StatesCenters for Disease Control and Prevention[71]and theMayo Clinic.[72]

From food

[edit]Basicfood-handling safetypractices can prevent or reduce the chances of becoming infected withT. gondii,such as washing unwashed fruits and vegetables, and avoiding raw or undercooked meat, poultry, and seafood. Other unsafe practices such as drinking unpasteurized milk or untreated water can increase odds of infection.[71]AsT. gondiiis commonly transmitted through ingesting microscopic cysts in the tissues of infected animals, meat that is not prepared to destroy these presents a risk of infection. Freezing meat for several days at subzero temperatures (0 °F or −18 °C) before cooking may break down all cysts, as they rarely survive these temperatures.[4]: 45 During cooking, whole cuts of red meat should be cooked to an internal temperature of at least 145 °F (63 °C).Medium raremeat is generally cooked between 130 and 140 °F (55 and 60 °C),[73]so cooking meat to at leastmediumis recommended. After cooking, a rest period of 3 min should be allowed before consumption. However, ground meat should be cooked to an internal temperature of at least 160 °F (71 °C) with no rest period. All poultry should be cooked to an internal temperature of at least 165 °F (74 °C). After cooking, a rest period of 3 min should be allowed before consumption.

From environment

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(February 2023) |

Oocysts in cat feces take at least a day tosporulate(to become infectious after they are shed), so disposing of cat litter daily greatly reduces the chance of infectious oocysts developing. As these can spread and survive in the environment for months, humans should wear gloves when gardening or working with soil, and should wash their hands promptly after disposing of cat litter. These precautions apply to outdoor sandboxes/play sand pits, which should be covered when not in use. Cat feces should never be flushed down a toilet.

Pregnant women are at higher risk of transmitting the parasite to their unborn child andimmunocompromisedpeople of acquiring a lingering infection. Because of this, they should not change or handle cat litter boxes. Ideally, cats should be kept indoors and fed only food that has low to no risk of carrying oocysts, such as commercial cat food or well-cooked table food.

Vaccination

[edit]No approved human vaccine exists againstToxoplasma gondii.[74][75]Research on human vaccines is ongoing.[74][76]

Forsheep,an approved live vaccine sold as Toxovax (fromMSD Animal Health) provides lifetime protection.[74][77][78]

There is currently no commercially available vaccine to preventT. gondiiinfection in cats. However, research into feline vaccines for toxoplasmosis is ongoing, with several candidates showing positive results in clinical trials.[74][79]

Treatment

[edit]In humans, active toxoplasmosis can be treated with a combination of drugs such aspyrimethamineandsulfadiazine,plusfolinic acid.Immune-compromised patients may need continuous treatment until/unless their immune system is restored.[80]

Environmental effects

[edit]In many parts of the world, where there are high populations of feral cats, there is an increased risk to the native wildlife due to increased infection ofToxoplasma gondii.It has been found that the serum concentrations ofT. gondiiin the wildlife population were increased where there are high amounts of cat populations. This creates a dangerous environment for organisms that have not evolved in cohabitation with felines and their contributing parasites.[81]

Impact on marine species

[edit]Minks and otters

[edit]Toxoplasmosis is one of the contributing factors toward mortality in southernsea otters,especially in areas where there is large urban run-off.[82]In their natural habitats, sea otters control sea urchin populations and, thus indirectly, control sea kelp forests. By enabling the growth of sea kelp, other marine populations are protected as well as CO2emissions are reduced due to the kelp's ability to absorb atmospheric carbon.[83]An examination on 105 beachcast otters revealed that 38.1% had parasitic infections, and 28% of said infections had resulted in protozoal meningoencephalitis deaths.[82]Toxoplasma gondiiwas found to be the root cause in 16.2% of these deaths, while 6.7% of the deaths were due to a closely related protozoan parasite known asSarcocystis neurona.[82]

Minks, being semiaquatic, are also susceptible to infection and being antibody-positive towardT. gondii.[84]Minks can follow a similar diet as otters and feasts on crustaceans, fish, and invertebrates, thus the transmission route follows a similar pattern to otters. Because of the mink's ability to transverse land more frequently, and often seen as an invasive species itself, minks are a bigger threat in transportingT. gondiito other mammalian species, rather than otters who have a more restrictive breadth.[84]

Black-footed penguins

[edit]Although under-studied, penguin populations, especially those that share an environment with the human population, are at-risk due to parasite infections, mainlyToxoplasmosis gondii.The main subspecies of penguins found to be infected byT. gondiiinclude wild Magellanic and Galapagos penguins, as well as blue and African penguins in captivity.[85]In one study, 57 (43.2%) of 132 serum samples of Magellanic penguins were found to haveT. gondii.The island that the penguin is located, Magdalena Island, is known to have no cat populations, but a very frequent human population, indicating the possibility of transmission.[85]

Histopathology

[edit]Examination of black-footed penguins with toxoplasmosis reveals hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, cranial hemorrhage, and necrotic kidneys.[86]Alveolar and hepatic tissue presents a high number of immune cells such as macrophages containing tachyzoites ofT. gondii.[86]Histopathological features in other animals affected with toxoplasmosis had tachyzoites in eye structures such as the retina which lead to blindness.[86]

Water transmission

[edit]The transmission of oocysts has been unknown, even though there have many documented cases of infection in marine species. Researchers have found that the oocytes ofT. gondiican survive in seawater for at least six months, with the amount of salt concentration not affecting its life cycle. There have been no studies on the ability ofT. gondiioocysts life cycle within freshwater environments, although infections are still present. One possible hypothesis of transmission is via amoeba species, particularlyAcanthamoebaspp., a species that is found in all water environments (fresh, brackish, and full-strength seawater). Normally, amoebas function as a natural filter, phagocytizing nutrients and bacteria found within the water. Some pathogens have used this to their advantage, however, and evolved to be able to avoid being broken down and, thus, survive encased in the amoeba – this includes Holosporaceae, Pseudomonaceae, Burkholderiacceae, among others.[87]Overall, this aids the pathogen in transportation but, also, protection from drugs and sterilizers that would, otherwise, cause death in the pathogen.[88]Studies have shown thatT. gondiioocysts can live within amoebas after being engulfed for at least 14 days without significant obliteration of the parasite.[89]The ability of the microorganism to survive in vitro is dependent on the microorganism itself, but there are a few overarching mechanisms present.T. gondiioocysts have been found to resist an acidic pH and, thus, are protected by the acidification found in endocytic vacuoles and lysosomes.[89]Phagocytosis further increases with the carbohydrate-rich surface membrane located on the amoebae.[90]The pathogen can be released either by lysis of the amoebae or by exocytosis, but this is understudied[91]

Impact on wild birds

[edit]Almost all species of birds that have been tested forToxoplasma gondiihave shown to be positive. The only bird species not reported with clinical symptoms of toxoplasmosis would be wild ducks, and there has only been one report found on domesticated ducks occurring in 1962.[92]Species with resistance towardT. gondiiinclude domestic turkeys,[93]owls, red tail hawks, and sparrows, depending on the strain ofT. gondii.[94]T. gondiiis considerably more severe in pigeons, particularly crown pigeons, ornamental pigeons, and pigeons originating from Australia and New Zealand. Typical onset is quick and usually results in death. Those that do survive often have chronic conditions of encephalitis and neuritis.[94]Similarly, canaries are observed to be just as severe as pigeons, but the clinical symptoms are more abnormal when compared to other species. Most of the infection affects the eye, causing blindness, choroidal lesions, conjunctivitis, atrophy of the eye, blepharitis, and chorioretinitis[94]Most of the time, the infection leads to death.

Current environmental efforts

[edit]Urbanization and global warming are extremely influential in the transmission ofT. gondii.[95]Temperature and humidity are huge factors in the sporulation stage: low humidity is always fatal to the oocysts, and they are also vulnerable to extreme temperatures.[95]Rainfall is also an important factor for survival of waterborne pathogens. Because increased rainfall directly increases the flow rate in rivers, the amount of flow into coastal areas is increased as well. This can spread waterborne pathogens over wide areas.

There is no effective vaccine forT. gondii,and research on a live vaccine is ongoing. Feeding cats commercially available food, rather than raw, undercooked meat, prevents felines from becoming a host for oocysts, as higher prevalence is in areas where raw meat is fed.[96]Researchers also suggest that owners restrict cats to live indoors and to be neutered or spayed to decrease stray cat populations and to reduce intermediate host interactions. It is suggested that fecal matter from litter boxes be collected daily, placed in a sealable bag, and disposed of in the trash rather than flushed in the toilet, so that water contamination is limited.[97]

Studies have found that wetlands with a high density of vegetation decrease the concentration of oocysts in water through two possible mechanisms. Firstly, vegetation decreases flow velocities, which enables more settling because of increased transport time.[97]Secondly, the vegetation can remove oocysts through its ability to mechanically strain the water, as well as through the process of adhesion (i.e. attachment to biofilms). Areas of erosion and destruction of coastal wetlands have been found to harbour increased concentrations ofT. gondiioocysts, which then flow into open coastal waters. Current physical and chemical treatments typically utilized in water treatment facilities have been proven to be ineffective againstT. gondii.Research has shown that UV-C disinfection of water containing oocysts results in inactivation and possible sterilization.[98]

Genome

[edit]Thegenomesof more than 60strainsofT. gondiihave been sequenced. Most are 60–80Mb in size and consist of 11–14chromosomes.[99][100]The major strains encode 7,800–10,000proteins,of which about 5,200 are conserved across RH, GT1, ME49, VEG.[99]A database, ToxoDB, has been established to document genomic information onToxoplasma.[101][102][103]

History

[edit]In 1908, while working at thePasteur InstituteinTunis,Charles NicolleandLouis Manceauxdiscovered a protozoan organism in the tissues of a hamster-like rodent known as thegundi,Ctenodactylus gundi.[31]Although Nicolle and Manceaux initially believed the organism to be a member of thegenusLeishmaniathat they described as"Leishmania gondii",they soon realized they had discovered a new organism entirely; they renamed itToxoplasma gondii.The new genus nameToxoplasmais a reference to its morphology:Toxo,from Greekτόξον(toxon,'arc, bow'), andπλάσμα(plasma,'shape, form') and the host in which it was discovered, the gundi (gondii).[104]The same year Nicolle and Mancaeux discoveredT. gondii,Alfonso Splendore identified the same organism in arabbitinBrazil.However, he did not give it a name.[31]In 1914, Italian tropicalistAldo Castellani"was first to suspect that toxoplasmosis could affect humans".[105]

The first conclusive identification ofT. gondiiin humans was in an infant girl delivered full term byCaesarean sectionon May 23, 1938, atBabies' HospitalinNew York City.[31]The girl began havingseizuresat three days of age, and doctors identifiedlesionsin themaculaeof both of her eyes. When she died at one month of age, anautopsywas performed.Lesionsdiscovered in her brain and eye tissue were found to have both free and intracellularT. gondii.[31]Infected tissue from the girl washomogenizedandinoculatedintracerebrally into rabbits and mice; they then developedencephalitis.Later,congenitaltransmission was confirmed in many other species, particularly infected sheep and rodents.

The possibility ofT. gondiitransmission via consumption of undercooked meat was first proposed by D. Weinman and A.H Chandler in 1954.[31]In 1960, the relevant cyst wall were shown to dissolve in the proteolytic enzymes found in the stomach, releasing infectious bradyzoites into the stomach (which pass into the intestine). The hypothesis of transmission via consumption of undercooked meat was tested in anorphanageinParisin 1965; incidence ofT. gondiirose from 10% to 50% after a year of adding two portions of cooked-rare beef or horse meat to many orphans' daily diets, and to 100% among those fed cooked-rare lamb chops.[31]

A 1959Mumbai-based study found there prevalence in strictvegetarianswas similar to that of non-vegetarians. This raised the possibility of a third major route of infection, beyond congenital and non well-cooked meat carnivorous transmission.[31]

In 1970, oocysts were found in (cat) feces. Thefecal–oral routeof infection via oocysts was demonstrated.[31]In the 1970s and 1980s feces of a vast range of infected animal species was tested to see if it contained oocysts—at least 17 species offelidsshed oocysts, but no non-felid has been shown to allowT. gondiisexual reproduction (leading to oocyst shedding).[31]

In 1984 Elmer R. Pfefferkorn published his discovery that treatment of humanfibroblastswith human recombinantinterferon gammablocks the growth ofT. gondii.[106]

Behavioral differences of infected hosts

[edit]There are many instances where behavioural changes were reported in rodents withT. gondii.The changes seen were a reduction in their innate dislike of cats, which made it easier for cats to prey on the rodents. In an experiment conducted by Berdoy and colleagues, the infected rats showed preference for the cat odour area versus the area with the rabbit scent, therefore making it easier for the parasite to take its final step in its definitive feline host.[7]This is an example of theextended phenotypeconcept, that is, the idea that the behaviour of the infected animal changes in order to maximize survival of the genes that increase predation of the intermediate rodent host.[107]

- Differences in sex-dependent behavior observed in infected hosts compared to non-infected individuals can be attributed to differences in testosterone. Infected males had higher levels of testosterone while infected females had significantly lower levels, compared to their non-infected equivalents.[108]

- Looking at humans, studies using theCattell's 16 Personality Factor questionnairefound that infected men scored lower on Factor G (superego strength/rule consciousness) and higher on FactorL (vigilance) while the opposite pattern was observed for infected women.[109]Such men were more likely to disregard rules and were more expedient, suspicious, and jealous. On the other hand, women were more warm-hearted, outgoing, conscientious, and moralistic.[109]

- Published research has also indicated thatT. gondiiinfection could potentially promote changes in a person's political beliefs and values. Those who are infected with the parasite tend to exhibit a higher degree of "us versus them" thinking.[110][111][112]

- Mice infected withT. gondiihave a worse motor performance than non-infected mice.[113][114]Thus, a computerized simple reaction test was given to both infected and non-infected adults. It was found that the infected adults performed much more poorly and lost their concentration more quickly than thecontrol group.But, the effect of the infection only explains less than 10% of the variability in performance[109](i.e., there could be other confounding factors).

- Correlation has also been observed betweenseroprevalenceofT. gondiiin humans and increased risk of traffic accidents. Infected subjects have a 2.65 times higher risk of getting into a traffic accident.[115]A Turkish study confirmed this holds true among drivers.[116]

- This parasite has been associated with many neurological disorders such asschizophrenia.In a meta-analysis of 23 studies that met inclusion criteria, the seroprevalence of antibodies toT. gondiiin people with schizophrenia is significantly higher than in control populations (OR=2.73, P<0.000001).[117]

- A 2009 summary of studies found that suicide attempters had far more indicative (IgG) antibodies than mental health inpatients without a suicide attempt.[118]Infection was also shown to be associated with suicide in women over the age of 60. (P<0.005)[119]

- Research on the linkage betweenT. gondiiinfection and entrepreneurial behavior showed that students who tested positive forT. gondiiexposure were 1.4 times more likely to major in business and 1.7 times more likely to have an emphasis in "management and entrepreneurship". Among 197 participants of entrepreneurship events,T. gondiiexposure was correlated with being 1.8 times more likely to have started their own business.[120]

- Another population-representative study with 7440 people in the United States found thatToxoplasmainfection was 2.4 fold more common in people who had a history of manic and depression symptoms (bipolar disorder Type 1) compared to the general population.[121]

As mentioned before, these results of increased proportions of people seropositive for the parasite in cases of these neurological disorders do not necessarily indicate a causal relationship between the infection and disorder. It is also important to mention that in 2016 a population-representative birth cohort study which was done, to test a hypothesis thattoxoplasmosisis related to impairment in brain and behaviour measured by a range of phenotypes including neuropsychiatric disorders, poor impulse control, personality and neurocognitive deficits. The results of this study did not support the results in the previously mentioned studies, more than marginally. None of the P-values showed significance for any outcome measure. Thus, according to this study, the presence ofT. gondiiantibodies is not correlated to increase susceptibility to any of the behaviour phenotypes (except possibly to a higher rate of unsuccessful attempted suicide). This team did not observe any significant association betweenT. gondiiseropositivity andschizophrenia.The team notes that the null findings might be a false negative due to low statistical power because of small sample sizes but against this weights that their setup should avoid some possibilities for errors in the about 40 studies that did show a positive correlation. They concluded that further studies should be performed.[122]

The mechanism behind behavioral changes is partially attributed to increased dopamine metabolism,[123]which can be neutralized by dopamine antagonist medications.[124]T. gondiihas two genes that code for a bifunctionalphenylalanineandtyrosine hydroxylase,two important and rate-limiting steps of dopamine biosynthesis. One of the genes is constitutively expressed, while the other is only produced during cyst development.[125][126]In addition to additional dopamine production,T. gondiiinfection also produces long-lasting epigenetic changes in animals that increase the expression ofvasopressin,a probable cause of alterations that persist after the clearance of the infection.[127]

In 2022, a study published inCommunications Biologyof a well-documented population of wolves studied throughout their lives, suggested thatT. gondiialso may have a significant effect on their behavior.[128]It suggested that infection with this parasite emboldened infected wolves into behavior that determined leadership roles and influenced risk-taking behavior, perhaps even motivating establishment of new independent packs that they would establish and lead in behavior patterns differing from that of the packs into which they were born. The study determined that at times, an infected wolf would become the only breeding male in a pack, leading to a significant effect on another species byT. gondii.

Potential medical use

[edit]In July 2024, a study published inNature Microbiologyshowed thatT. gondiican be engineered to deliver theMECP2protein, a therapeutic target ofRett syndrome,to the brain of infected mice.[129][130]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Nicolle, C.; Manceaux, L. (1908)."Sur une infection à corps de Leishman (ou organismes voisins) du Gondi".Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences(in French).147(2):763–66.

- ^Nicolle, C.; Manceaux, L. (1909)."Sur un Protozoaire nouveau du Gondi".Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences(in French).148(1):369–72.

- ^Dardé, M. L.; Ajzenberg, D.; Smith, J. (2011)."Population structure and epidemiology ofToxoplasma gondii".In Weiss, L. M.; Kim, K. (eds.).Toxoplasma Gondii: The Model Apicomplexan. Perspectives and Methods.Amsterdam, Boston, Heidelberg, London, New York:Elsevier.pp. 49–80.doi:10.1016/B978-012369542-0/50005-2.ISBN9780123695420.

- ^abcdefghDubey, J. P. (2010)."General Biology".Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans(2nd ed.). Boca Raton / London / New York: Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 1–20.ISBN9781420092370.Retrieved1 February2019.

- ^"CDC - Toxoplasmosis - Biology".17 March 2015.Retrieved14 June2015.

- ^abKnoll, Laura J.; Dubey, J. P.; Wilson, Sarah K.; Genova, Bruno Martorelli Di (1 July 2019)."Intestinal delta-6-desaturase activity determines host range forToxoplasmasexual reproduction ".bioRxiv.17(8): 688580.doi:10.1101/688580.PMC6701743.PMID31430281.

- ^abcdBerdoy, M.; Webster, J. P.; Macdonald, D. W. (August 2000)."Fatal attraction in rats infected withToxoplasma gondii".Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences.267(1452): 1591–94.doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1182.PMC1690701.PMID11007336.

- ^Webster, J. P. (May 2007)."The effect ofToxoplasma gondiion animal behavior: playing cat and mouse ".Schizophrenia Bulletin.33(3): 752–756.doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl073.PMC2526137.PMID17218613.

- ^abWebster, J. P.; Kaushik, M.; Bristow, G. C.; McConkey, G. A. (January 2013)."Toxoplasma gondii infection, from predation to schizophrenia: can animal behaviour help us understand human behaviour?".The Journal of Experimental Biology.216(Pt 1): 99–112.doi:10.1242/jeb.074716.PMC3515034.PMID23225872.

- ^Boillat, M.; Hammoudi, P. M.; Dogga, S. K.; Pagès, S.; Goubran, M.; Rodriguez, I.; Soldati-Favre, D. (2020)."Neuroinflammation-associated Aspecific Manipulation of Mouse Predator Fear byToxoplasma gondii".Cell Reports.30(2). pp. 320–334.e6.doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.019.PMC6963786.PMID31940479.

- ^Hari Dass, S. A.; Vyas, A. (December 2014). "Toxoplasma gondiiinfection reduces predator aversion in rats through epigenetic modulation in the host medial amygdala ".Molecular Ecology.23(24): 6114–22.Bibcode:2014MolEc..23.6114H.doi:10.1111/mec.12888.PMID25142402.S2CID45290208.

- ^Flegr, J.; Markoš, A. (December 2014)."Masterpiece of epigenetic engineering – howToxoplasma gondiireprogrammes host brains to change fear to sexual attraction ".Molecular Ecology.23(24): 5934–5936.Bibcode:2014MolEc..23.5934F.doi:10.1111/mec.13006.PMID25532868.S2CID17253786.

- ^ab"CDC Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection) Disease".Retrieved12 March2013.

- ^abcFlegr, J.; Prandota, J.; Sovičková, M.; Israili, Z. H. (March 2014)."Toxoplasmosis – a global threat. Correlation of latent toxoplasmosis with specific disease burden in a set of 88 countries".PLOS ONE.9(3): e90203.Bibcode:2014PLoSO...990203F.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090203.PMC3963851.PMID24662942.

Toxoplasmosis is becoming a global health hazard as it infects 30–50% of the world human population. Clinically, the life-long presence of the parasite in tissues of a majority of infected individuals is usually considered asymptomatic. However, a number of studies show that this 'asymptomatic infection' may also lead to development of other human pathologies.... The seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis correlated with various disease burden. Statistical associations does not necessarily mean causality. The precautionary principle suggests, however, that possible role of toxoplasmosis as a triggering factor responsible for development of several clinical entities deserves much more attention and financial support both in everyday medical practice and future clinical research.

- ^Cook, T. B.; Brenner, L. A.; Cloninger, C. R.; Langenberg, P.; Igbide, A.; Giegling, I.; Hartmann, A. M.; Konte, B.; Friedl, M.; Brundin, L.; Groer, M. W.; Can, A.; Rujescu, D.; Postolache, T. T. (January 2015). ""Latent" infection with Toxoplasma gondii: association with trait aggression and impulsivity in healthy adults ".Journal of Psychiatric Research.60:87–94.doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.09.019.PMID25306262.

- ^Flegr, J. (January 2013)."Influence of latent Toxoplasma infection on human personality, physiology and morphology: pros and cons of the Toxoplasma-human model in studying the manipulation hypothesis".The Journal of Experimental Biology.216(Pt 1): 127–33.doi:10.1242/jeb.073635.PMID23225875.

- ^Burgdorf, K. S.; Trabjerg, B. B.; Pedersen, M. G.; Nissen, J.; Banasik, K.; Pedersen, O. B.; et al. (2019)."Large-scale study of Toxoplasma and Cytomegalovirus shows an association between infection and serious psychiatric disorders".Brain, Behavior, and Immunity.79:152–158.doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2019.01.026.PMID30685531.

- ^Parlog, A.; Schlüter, D.; Dunay, I. R. (March 2015). "Toxoplasma gondii-induced neuronal alterations".Parasite Immunology.37(3): 159–70.doi:10.1111/pim.12157.hdl:10033/346575.PMID25376390.S2CID17132378.

- ^Blanchard, N.; Dunay, I. R.; Schlüter, D. (March 2015)."Persistence of Toxoplasma gondii in the central nervous system: a fine-tuned balance between the parasite, the brain and the immune system".Parasite Immunology.37(3): 150–58.doi:10.1111/pim.12173.hdl:10033/346515.PMID25573476.S2CID1711188.

- ^Pearce, B. D.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; Jones, J. L. (2012)."The Relationship Between Toxoplasma Gondii Infection and Mood Disorders in the Third National Health and Nutrition Survey".Biological Psychiatry.72(4): 290–95.doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.003.PMC4750371.PMID22325983.

- ^de Barros, J. L.; Barbosa, I. G.; Salem, H.; Rocha, N. P.; Kummer, A.; Okusaga, O. O.; Soares, J. C.; Teixeira; A. L. (February 2017). "Is there any association between Toxoplasma gondii infection and bipolar disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis".Journal of Affective Disorders.209:59–65.doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.016.PMID27889597.

- ^Flegr, J.; Lenochová, P.; Hodný, Z.; Vondrová, M (November 2011)."Fatal attraction phenomenon in humans: cat odour attractiveness increased for toxoplasma-infected men, but decreased for infected women".PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.5(11): e1389.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001389.PMC3210761.PMID22087345.

- ^Sugden, Karen; Moffitt, Terrie E.; Pinto, Lauriane; Poulton, Richie; Williams, Benjamin S.; Caspi, Avshalom (17 February 2016)."Is Toxoplasma Gondii Infection Related to Brain and Behavior Impairments in Humans? Evidence from a Population-Representative Birth Cohort".PLOS ONE.11(2): e0148435.Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1148435S.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148435.PMC4757034.PMID26886853.

- ^"Evolutionary puzzle of Toxoplasma gondii with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis".9 April 2020.Retrieved20 September2024.

- ^"Cat parasite linked to mental illness, schizophrenia".CBS. 5 June 2015.Retrieved23 September2015.

- ^"CDC – About Parasites".Retrieved12 March2013.

- ^Pappas, G.; Roussos, N.; Falagas, M. E. (October 2009). "Toxoplasmosis snapshots: global status of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence and implications for pregnancy and congenital toxoplasmosis".International Journal for Parasitology.39(12): 1385–94.doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.04.003.PMID19433092.

- ^Bigna, Jean Joel; Tochie, Joel Noutakdie; Tounouga, Dahlia Noelle; Bekolo, Anne Olive; Ymele, Nadia S.; Youda, Emilie Lettitia; Sime, Paule Sandra; Nansseu, Jobert Richie (21 July 2020)."Global, regional, and country seroprevalence ofToxoplasma gondiiin pregnant women: a systematic review, modelling and meta-analysis ".Scientific Reports.10(1): 12102.Bibcode:2020NatSR..1012102B.doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69078-9.ISSN2045-2322.PMC7374101.PMID32694844.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvWeiss LM, Kim K (2011).Toxoplasma Gondii:The Model Apicomplexan: Perspectives and Methods(2nd ed.). Academic Press.ISBN9780080475011.Retrieved12 March2013.

- ^Dubey, J. P.; Ferreira, L. R.; Martins, J.; Jones, J. L. (October 2011)."Sporulation and survival ofToxoplasma gondiioocysts in different types of commercial cat litter ".The Journal of Parasitology.97(5): 751–54.doi:10.1645/GE-2774.1.PMID21539466.S2CID41292680.

- ^abcdefghijklmDubey, J. P. (July 2009). "History of the discovery of the life cycle ofToxoplasma gondii".International Journal for Parasitology.39(8): 877–82.doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.01.005.PMID19630138.

- ^abcKapperud, G.; Jenum, P. A.; Stray-Pedersen, B.; Melby, K. K.; Eskild, A.; Eng, J. (August 1996)."Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in pregnancy. Results of a prospective case-control study in Norway".American Journal of Epidemiology.144(4): 405–12.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008942.PMID8712198.

- ^Dubey, J. P. (July 1998)."Advances in the life cycle ofToxoplasma gondii".International Journal for Parasitology.28(7): 1019–24.doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(98)00023-X.PMID9724872.

- ^abMoré, Gastón; Venturini, Maria Cecilia; Pardini, Lais; Unzaga, Juan Manuel (8 November 2017).Parasitic Protozoa of Farm Animals and Pets.Cham, Switzerland:Springer.ISBN9783319701318.

- ^abcdRobert-Gangneux, F.; Dardé, M. L. (April 2012)."Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis".Clinical Microbiology Reviews.25(2): 264–96.doi:10.1128/CMR.05013-11.PMC3346298.PMID22491772.

- ^Markus, M. B. (1987). "Terms for coccidian merozoites".Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology.81(4): 463.doi:10.1080/00034983.1987.11812147.PMID3446034.

- ^abcdefMiller, C. M.; Boulter, N. R.; Ikin, R. J.; Smith, N. C. (January 2009). "The immunobiology of the innate response toToxoplasma gondii".International Journal for Parasitology.39(1): 23–39.doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.08.002.PMID18775432.

- ^"CDC Toxoplasmosis – Microscopy Findings".Archived fromthe originalon 6 November 2013.Retrieved13 March2013.

- ^Robbins, Clarence R. (2012).Chemical and Physical Behavior of Human Hair.Springer. p. 585.ISBN9783642256103.Retrieved12 March2013.

- ^Jones, J. L.; Dubey, J. P. (September 2012)."Foodborne toxoplasmosis".Clinical Infectious Diseases.55(6): 845–51.doi:10.1093/cid/cis508.PMID22618566.

- ^"Parasite Shed in Cat Feces Kills Sea Otters – California Sea Grant"(PDF).www-csgc.ucsd.edu.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 1 July 2010.Retrieved14 March2018.

- ^Khan, A.; Böhme, U.; Kelly, K. A.; Adlem, E.; Brooks, K.; Simmonds, M.; Mungall, K.; Quail, M. A.; Arrowsmith, C.; Chillingworth, T.; Churcher, C.; Harris, D.; Collins, M.; Fosker, N.; Fraser, A.; Hance, Z.; Jagels, K.; Moule, S.; Murphy, L.; O'Neil, S.; Rajandream, M. A.; Saunders, D.; Seeger, K.; Whitehead, S.; Mayr, T.; Xuan, X.; Watanabe, J.; Suzuki, Y.; Wakaguri, H.; Sugano, S.; Sugimoto, C.; Paulsen, I.; Mackey, A. J.; Roos, D. S.; Hall, N.; Berriman, M.; Barrell, B.; Sibley, L. D.; Ajioka, J. W. (2006)."Common inheritance of chromosome Ia associated with clonal expansion ofToxoplasma gondii".Genome Research.16(9): 1119–1125.doi:10.1101/gr.5318106.PMC1557770.PMID16902086.

- ^Dubey, J. P.; Velmurugan, G. V.; Rajendran, C.; Yabsley, M. J.; Thomas, N. J.; Beckmen, K. B.; Sinnett, D.; Ruid, D.; Hart, J.; Fair, P. A.; McFee, W. E.; Shearn-Bochsler, V.; Kwok, O. C.; Ferreira, L. R.; Choudhary, S.; Faria, E. B.; Zhou, H.; Felix, T. A.; Su, C. (2011)."Genetic characterisation ofToxoplasma gondiiin wildlife from North America revealed widespread and high prevalence of the fourth clonal type ".International Journal for Parasitology.41(11): 1139–1147.doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.06.005.PMID21802422.S2CID16654819.

- ^abFrénal, Karine; Dubremetz, Jean-François; Lebrun, Maryse; Soldati-Favre, Dominique (4 September 2017)."Gliding motility powers invasion and egress in Apicomplexa".Nature Reviews Microbiology.15(11).Nature Portfolio:645–660.doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2017.86.ISSN1740-1526.PMID28867819.S2CID23129560.

- ^abcBrochet, Mathieu; Billker, Oliver (12 February 2016)."Calcium signalling in malaria parasites".Molecular Microbiology.100(3).Wiley:397–408.doi:10.1111/mmi.13324.ISSN0950-382X.PMID26748879.S2CID28504228.

- ^abRigoulet, J.; Hennache, A.; Lagourette, P.; George, C.; Longeart, L.; Le Net, J. L.; Dubey, J. P. (2014)."Toxoplasmosis in a bar-shouldered dove (Geopelia humeralis) from the Zoo of Clères, France".Parasite.21:62.doi:10.1051/parasite/2014062.PMC4236686.PMID25407506.

- ^Hehl, Adrian B.; Basso, Walter U.; Lippuner, Christoph; Ramakrishnan, Chandra; Okoniewski, Michal; Walker, Robert A.; Grigg, Michael E.; Smith, Nicholas C.; Deplazes, Peter (13 February 2015)."Asexual expansion of Toxoplasma gondii merozoites is distinct from tachyzoites and entails expression of non-overlapping gene families to attach, invade, and replicate within feline enterocytes".BMC Genomics.16(1): 66.doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1225-x.PMC4340605.PMID25757795.

- ^Behnke, Michael S.; Zhang, Tiange P.; Dubey, Jitender P.; Sibley, L. David (8 May 2014)."Toxoplasma gondii merozoite gene expression analysis with comparison to the life cycle discloses a unique expression state during enteric development".BMC Genomics.15(1): 350.doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-350.PMC4035076.PMID24885521.

- ^Genova, Bruno Martorelli Di; Wilson, Sarah K.; Dubey, J. P.; Knoll, Laura J. (20 August 2019)."Intestinal delta-6-desaturase activity determines host range for Toxoplasma sexual reproduction".PLOS Biology.17(8): e3000364.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000364.PMC6701743.

- ^Farhat, Dayana C.; Swale, Christopher; Dard, Céline; Cannella, Dominique; Ortet, Philippe; Barakat, Mohamed; Sindikubwabo, Fabien; Belmudes, Lucid; De Bock, Pieter-Jan; Couté, Yohann; Bougdour, Alexandre; Hakimi, Mohamed-Ali (April 2020)."A MORC-driven transcriptional switch controls Toxoplasma developmental trajectories and sexual commitment".Nature Microbiology.5(4): 570–583.doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0674-4.PMC7104380.PMID32094587.

- ^Antunes, Ana Vera; Shahinas, Martina; Swale, Christopher; Farhat, Dayana C.; Ramakrishnan, Chandra; Bruley, Christophe; Cannella, Dominique; Robert, Marie G.; Corrao, Charlotte; Couté, Yohann; Hehl, Adrian B.; Bougdour, Alexandre; Coppens, Isabelle; Hakimi, Mohamed-Ali (11 January 2024)."In vitro production of cat-restricted Toxoplasma pre-sexual stages".Nature.625(7994): 366–376.doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06821-y.PMC10781626.PMID38093015.

- ^Parks, S.; Avramopoulos, D.; Mulle, J.; McGrath, J.; Wang, R.; Goes, F. S.; Conneely, K.; Ruczinski, I.; Yolken, R.; Pulver, A. E. (May 2018). "HLA typing using genome wide data reveals susceptibility types for infections in a psychiatric disease enriched sample".Brain, Behavior, and Immunity.70:203–213.doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2018.03.001.PMID29574260.S2CID4482168.

- ^abcHenriquez, S. A.; Brett, R.; Alexander, J.; Pratt, J.; Roberts, C. W. (2009). "Neuropsychiatric disease and Toxoplasma gondii infection".Neuroimmunomodulation.16(2): 122–133.doi:10.1159/000180267.PMID19212132.S2CID7382051.

- ^Konsman, J. P.; Parnet, P.; Dantzer, R. (March 2002). "Cytokine-induced sickness behaviour: mechanisms and implications".Trends in Neurosciences.25(3): 154–59.doi:10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02088-9.PMID11852148.S2CID29779184.

- ^abcTenter, A. M.; Heckeroth, A. R.; Weiss, L. M. (November 2000)."Toxoplasma gondii:from animals to humans ".International Journal for Parasitology.30(12–13): 1217–58.doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00124-7.PMC3109627.PMID11113252.

- ^abcdJones, J. L.; Dargelas, V.; Roberts, J.; Press, C.; Remington, J. S.; Montoya, J. G. (September 2009)."Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States".Clinical Infectious Diseases.49(6): 878–84.doi:10.1086/605433.PMID19663709.

- ^abCook, A. J.; Gilbert, R. E.; Buffolano, W.; Zufferey, J.; Petersen, E.; Jenum, P. A.; Foulon, W.; Semprini, A. E.; Dunn, D. T. (July 2000)."Sources of toxoplasma infection in pregnant women: European multicentre case-control study. European Research Network on Congenital Toxoplasmosis".BMJ.321(7254): 142–47.doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7254.142.PMC27431.PMID10894691.

- ^Sakikawa, M.; Noda, S.; Hanaoka, M.; Nakayama, H.; Hojo, S.; Kakinoki, S.; Nakata, M.; Yasuda, T.; Ikenoue, T.; Kojima, T. (March 2012)."Anti-Toxoplasma antibody prevalence, primary infection rate, and risk factors in a study of toxoplasmosis in 4,466 pregnant women in Japan".Clinical and Vaccine Immunology.19(3): 365–67.doi:10.1128/CVI.05486-11.PMC3294603.PMID22205659.

- ^abDubey, J. P.; Hill, D. E.; Jones, J. L.; Hightower, A. W.; Kirkland, E.; Roberts, J. M.; Marcet, P. L.; Lehmann, T.; Vianna, M. C.; Miska, K.; Sreekumar, C.; Kwok, O. C.; Shen, S. K.; Gamble, H. R. (October 2005). "Prevalence of viable Toxoplasma gondii in beef, chicken, and pork from retail meat stores in the United States: risk assessment to consumers".The Journal of Parasitology.91(5): 1082–93.doi:10.1645/ge-683.1.PMID16419752.S2CID26649961.

- ^Mai, K.; Sharman, P. A.; Walker, R. A.; Katrib, M.; De Souza, D.; McConville, M. J.; Wallach, M. G.; Belli, S. I.; Ferguson, D. J.; Smith, N. C. (March 2009)."Oocyst wall formation and composition in coccidian parasites".Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz.104(2): 281–89.doi:10.1590/S0074-02762009000200022.hdl:1807/57649.PMID19430654.

- ^Siegel, S. E.; Lunde, M. N.; Gelderman, A. H.; Halterman, R. H.; Brown, J. A.; Levine, A. S.; Graw, R. G. (April 1971)."Transmission of toxoplasmosis by leukocyte transfusion".Blood.37(4): 388–94.doi:10.1182/blood.V37.4.388.388.PMID4927414.

- ^Gallas-Lindemann, C.; Sotiriadou, I.; Mahmoodi, M. R.; Karanis, P. (February 2013). "Detection of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in different water resources by Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP)".Acta Tropica.125(2): 231–36.doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.10.007.PMID23088835.

- ^Alvarado-Esquivel, C.; Liesenfeld, O.; Márquez-Conde, J. A.; Estrada-Martínez, S.; Dubey, J. P. (October 2010). "Seroepidemiology of infection with Toxoplasma gondii in workers occupationally exposed to water, sewage, and soil in Durango, Mexico".The Journal of Parasitology.96(5): 847–50.doi:10.1645/GE-2453.1.PMID20950091.S2CID23241017.

- ^Esmerini, P. O.; Gennari, S. M.; Pena, H. F. (May 2010)."Analysis of marine bivalve shellfish from the fish market in Santos city, São Paulo state, Brazil, for Toxoplasma gondii".Veterinary Parasitology.170(1–2): 8–13.doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.01.036.PMID20197214.

- ^Dattoli, V. C.; Veiga, R. V.; Cunha, S. S.; Pontes-de-Carvalho, L.; Barreto, M. L.; Alcantara-Neves, N. M. (December 2011)."Oocyst ingestion as an important transmission route of Toxoplasma gondii in Brazilian urban children".The Journal of Parasitology.97(6): 1080–84.doi:10.1645/GE-2836.1.PMC7612830.PMID21740247.S2CID7170467.

- ^Gross, Rachel (20 September 2016)."The Moral Cost of Cats".Smithsonian Magazine.Smithsonian Institution.Retrieved23 October2020.

- ^Bobić, B.; Jevremović, I.; Marinković, J.; Sibalić, D.; Djurković-Djaković, O. (September 1998). "Risk factors for Toxoplasma infection in a reproductive age female population in the area of Belgrade, Yugoslavia".European Journal of Epidemiology.14(6): 605–10.doi:10.1023/A:1007461225944.PMID9794128.S2CID9423818.

- ^Dass, S. A.; Vasudevan, A.; Dutta, D.; Soh, L. J.; Sapolsky, R. M.; Vyas, A. (2011)."Protozoan parasiteToxoplasma gondiimanipulates mate choice in rats by enhancing attractiveness of males ".PLOS ONE.6(11): e27229.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...627229D.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027229.PMC3206931.PMID22073295.

- ^Arantes, T. P.; Lopes, W. D.; Ferreira, R. M.; Pieroni, J. S.; Pinto, V. M.; Sakamoto, C. A.; Costa, A. J. (October 2009). "Toxoplasma gondii:Evidence for the transmission by semen in dogs ".Experimental Parasitology.123(2): 190–94.doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2009.07.003.PMID19622353.

- ^J., Gutierrez; O'Donovan, J.; Williams, E.; Proctor, A.; Brady, C.; Marques, P. X.; Worrall, S.; Nally, J. E.; McElroy, M.; Bassett, H.; Sammin, D.; Buxton, D.; Maley, S.; Markey, B. K. (August 2010). "Detection and quantification ofToxoplasma gondiiin ovine maternal and foetal tissues from experimentally infected pregnant ewes using real-time PCR ".Veterinary Parasitology.172(1–2): 8–15.doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.04.035.PMID20510517.

- ^ab"CDC: Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection) – Prevention & Control".Retrieved13 March2013.

- ^"Mayo Clinic – Toxoplasmosis – Prevention".Retrieved13 March2013.

- ^Green, Aliza (2005).Field Guide to Meat.Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books. pp.294–95.ISBN9781594740176.

- ^abcdZhang Y, Li D, Lu S, Zheng B (October 2022)."Toxoplasmosis vaccines: what we have and where to go?".npj Vaccines.7(1): 131.doi:10.1038/s41541-022-00563-0.PMC9618413.PMID36310233.

- ^Verma, R.; Khanna, P. (February 2013)."Development of Toxoplasma gondii vaccine: A global challenge".Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics.9(2): 291–93.doi:10.4161/hv.22474.PMC3859749.PMID23111123.

- ^"TOXPOX Result In Brief – Vaccine against Toxoplasmosis".CORDIS, European Commission. 14 January 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 22 December 2015.Retrieved11 December2015.

- ^"TOXOVAX®".MSD Animal Health. Archived fromthe originalon 22 January 2016.Retrieved10 November2015.

- ^Hasan T, Nishikawa Y (2022)."Advances in vaccine development and the immune response against toxoplasmosis in sheep and goats".Frontiers in Veterinary Science.9:951584.doi:10.3389/fvets.2022.951584.PMC9453163.PMID36090161.

- ^Bonačić Marinović AA, Opsteegh M, Deng H, Suijkerbuijk AW, van Gils PF, van der Giessen J (December 2019)."Prospects of toxoplasmosis control by cat vaccination".Epidemics.30:100380.doi:10.1016/j.epidem.2019.100380.PMID31926434.

- ^"CDC - Toxoplasmosis - Treatment".U.S. Centers for Disease Control. 28 February 2019.Retrieved13 July2021.

- ^Hollings, T.; Jones, M.; Mooney, N.; McCallum, H. (2013)."Wildlife disease ecology in changing landscapes: Mesopredator release and toxoplasmosis".International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife.2:110–118.doi:10.1016/j.ijppaw.2013.02.002.PMC3862529.PMID24533323.

- ^abcConrad, P. A.; Miller, M. A.; Kreuder, C.; James, E. R.; Mazet, J.; Dabritz, H.; Jessup, D. A.; Gulland, Frances; Grigg, M. E. (October 2005). "Transmission ofToxoplasma:Clues from the study of sea otters as sentinels ofToxoplasma gondiiflow into the marine environment ".International Journal for Parasitology.35(11–12): 1155–1168.doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.002.PMID16157341.

- ^"Sea Otter".Defenders of Wildlife.2020.

- ^abAhlers, Adam A.; Mitchell, Mark A.; Dubey, Jitender P.; Schooley, Robert L.; Heske, Edward J. (1 April 2015). "Risk Factors forToxoplasma gondiiExposure in Semiaquatic Mammals in a Freshwater Ecosystem ".Wildlife Diseases.51(2): 488–492.doi:10.7589/2014-03-071.PMID25574808.

- ^abAcosta, I. C. L.; Souza-Filho, A. F.; Muñoz-Leal, S.; Soares, H. S.; Heinemann, M. B.; Moreno, L.; González-Acuña, D.; Gennari, S. M. (April 2019). "Evaluation of antibodies againstToxoplasma gondiiandLeptospiraspp. in Magellanic penguins (Speniscus magellanicus) on Magdalena Island, Chile ".Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports.16:1–4.doi:10.1016/j.vprsr.2019.100282.PMID31027597.S2CID91996679.

- ^abcPloeg, M.; Ultee, T.; Kik, M. (2011). "Disseminated Toxoplasmosis in Black-footed Penguins (Spheniscus demersus) ".Avian Diseases.55(4): 701–703.doi:10.1637/9700-030411-Case.1.PMID22312996.S2CID31105636.

- ^Greub, Gilbert; Raoult, Didier (April 2004)."Microorganisms Resistant to Free-living Amoebae".Clinical Microbiology Reviews.17(2): 413–433.doi:10.1128/CMR.17.2.413-433.2004.PMC387402.PMID15084508.

- ^Cirillo, Jeffrey D.; Falkow, Stanley; Tompkins, Lucy S.; Bermundez, Luiz E. (September 1997)."Interaction ofMycobacterium aviumwith environmental amoebae enhances virulence ".Infection and Immunity.65(9): 3759–3767.doi:10.1128/iai.65.9.3759-3767.1997.PMC175536.PMID9284149.

- ^abWiniecka-Krusnell, Jadwiga; Dellacasa-Lindberg, Isabel; Dubey, J. P.; Barragan, Antonio (February 2009). "Toxoplasma gondii:Uptake and survival of oocysts in free-living amoebae ".Experimental Parasitology.121(2): 124–131.doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2008.09.022.PMID18992742.

- ^Elloway, E. A. G.; Armstrong, R. A.; Bird, R. A.; Kelly, S. L.; Smith, S. N. (1 December 2004). "Analysis ofAcanthamoeba polyphagasurface carbohydrate exposure by FITC-lectin binding and fluorescence evaluation ".Journal of Applied Microbiology.97(6): 1319–1325.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02430.x.PMID15546423.S2CID23877072.

- ^Paquet, Valérie E.; Charette, Steve J. (8 February 2016)."Amoeba-resisting bacteria found in multilamellar bodies secreted byDictyostelium discoideum:Social amoebae can also package bacteria ".FEMS Microbiology Ecology.92(3): fiw025.doi:10.1093/femsec/fiw025.hdl:20.500.11794/313.PMID26862140.

- ^Boehringer, Emilio Geronimo; Fornari, Oscar Elias; Boehringer, Irene K. (November 1962). "The first case ofT. gondiiin domestic ducks in Argentina ".Avian Diseases.6(4): 391–396.doi:10.2307/1587913.JSTOR1587913.

- ^Drobeck, Hans Peter; Manwell, Reginald D.; Bernstein, Emil; Dillon, Raymond D. (November 1953). "Further studies of toxoplasmosis in birds".American Journal of Epidemiology.59(3): 329–339.doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00034-1.PMID12031816.

- ^abcDubey, J. P. (June 2002). "A review of toxoplasmosis in wild birds".Veterinary Parasitology.106(2): 121–153.doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00034-1.PMID12031816.

- ^abYan, Chao; Liang, Li-Jun; Zheng, Kui-Yang; Zhu, Xing-Quan (10 March 2016)."Impact of environmental factors on the emergence, transmission and distribution ofToxoplasma gondii".Parasites & Vectors.9:137.doi:10.1186/s13071-016-1432-6.PMC4785633.PMID26965989.

- ^Elmore, Stacey A.; Jones, Jeffrey L.; Conrad, Patricia A.; Patton, Sharon; Lindsay, David S.; Dubey, J. P. (April 2010)."Toxoplasma gondii:Epidemiology, feline clinical aspects, and prevention ".Trends in Parasitology.26(4): 190–196.doi:10.1016/j.pt.2010.01.009.PMID20202907.

- ^abShapiro, Karen; Bahia-Oliveira, Lillian; Dixon, Brent; Dumètre, Aurélien; de Wit, Luiz A.; VanWormer, Elizabeth; Villena, Isabelle (April 2019)."Environmental transmission ofToxoplasma gondii:Oocysts in water, soil and food ".Food and Waterborne Parasitology.12:e00049.doi:10.1016/j.fawpar.2019.e00049.PMC7033973.PMID32095620.

- ^Dumètre, Aurélien; Le Bras, Caroline; Baffet, Maxime; Meneceur, Pascale; Dubey, J. P.; Derouin, Francis; Duguet, Jean-Pierre; Joveux, Michel; Moulin, Laurent (May 2008). "Effects of ozone and ultraviolet radiation treatments on the infectivity ofToxoplasma gondiioocysts ".Veterinary Parasitology.153(3–4): 209–213.doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.02.004.PMID18355965.

- ^abLau, Y. L.; Lee, W. C.; Gudimella, R.; Zhang, G.; Ching, X. T.; Razali, R.; Aziz, F.; Anwar, A.; Fong, M. Y. (29 June 2016)."Deciphering the Draft Genome ofToxoplasma gondiiRH Strain ".PLOS ONE.11(6): e0157901.Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157901L.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157901.PMC4927122.PMID27355363.

- ^Bontell, I. L.; Hall, N.; Ashelford, K. E.; Dubey, J. P.; Boyle, J. P.; Lindh, J.; Smith, J. E. (20 May 2009)."Whole genome sequencing of a natural recombinantToxoplasma gondiistrain reveals chromosome sorting and local allelic variants ".Genome Biology.10(5): R53.doi:10.1186/gb-2009-10-5-r53.PMC2718519.PMID19457243.

- ^Kissinger, J. C.; Gajria, B.; Li, L.; Paulsen, I. T.; Roos, D. S. (January 2003)."ToxoDB: accessing theToxoplasma gondiigenome ".Nucleic Acids Research.31(1): 234–36.doi:10.1093/nar/gkg072.PMC165519.PMID12519989.

- ^Gajria, B.; Bahl, A.; Brestelli, J.; Dommer, J.; Fischer, S.; Gao, X.; Heiges, M.; Iodice, J.; Kissinger, J. C.; Mackey, A. J.; Pinney, D. F.; Roos, D. S.; Stoeckert, C. J.; Wang, H.; Brunk, B. P. (January 2008)."ToxoDB: An integratedToxoplasma gondiidatabase resource ".Nucleic Acids Research.36(Database issue): D553–56.doi:10.1093/nar/gkm981.PMC2238934.PMID18003657.

- ^"ToxoDB: TheToxoplasmaGenomics Resource ".toxodb.org.Retrieved1 March2018.

- ^Flegr, Jaroslav; Prandota, Joseph; Sovičková, Michaela; Israili, Zafar H. (24 March 2014)."Toxoplasmosis – A Global Threat. Correlation of Latent Toxoplasmosis with Specific Disease Burden in a Set of 88 Countries".PLOS ONE.9(3): e90203.Bibcode:2014PLoSO...990203F.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090203.ISSN1932-6203.PMC3963851.PMID24662942.

- ^Norman, Jeremy M., ed. (1991).Morton's Medical Bibliography: An Annotated Check-list of Texts Illustrating the History of Medicine(5th ed.). Aldershot: Garrison and Morton / Scolar Press. p. 860 (§ 5535.1).

- ^Pfefferkorn, E. R. (1984)."Interferon gamma blocks the growth of Toxoplasma gondii in human fibroblasts by inducing the host cells to degrade tryptophan".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.81(3): 908–912.Bibcode:1984PNAS...81..908P.doi:10.1073/pnas.81.3.908.PMC344948.PMID6422465.

- ^McConkey, G. A.; Martin, H. L.; Bristow, G. C.; Webster, J. P. (January 2013)."Toxoplasma gondiiinfection and behaviour – location, location, location? ".The Journal of Experimental Biology.216(Pt 1): 113–19.doi:10.1242/jeb.074153.PMC3515035.PMID23225873.

- ^Flegr, J.; Lindová, J.; Kodym, P. (April 2008). "Sex-dependent toxoplasmosis-associated differences in testosterone concentration in humans".Parasitology.135(4): 427–31.doi:10.1017/S0031182007004064.PMID18205984.S2CID18829116.

- ^abcFlegr, J. (May 2007)."Effects of toxoplasma on human behavior".Schizophrenia Bulletin.33(3): 757–60.doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl074.PMC2526142.PMID17218612.

- ^Kopecky, R.; Příplatová, L.; Boschetti, S.; Talmont-Kaminski, K.; Flegr, J. (2022)."Le Petit Machiavellian Prince: Effects of Latent Toxoplasmosis on Political Beliefs and Values".Evolutionary Psychology.20(3): 1–13.doi:10.1177/14747049221112657.PMC10303488.PMID35903902.

- ^Ellwood, Beth (5 October 2022)."A common parasitic disease called toxoplasmosis might alter a person's political beliefs".PsyPost.Retrieved30 November2022.

- ^Singh, Ananya (10 October 2022)."A Common Parasite Could Be Altering People's Political Beliefs, Suggests Study".The Swaddle.Retrieved30 November2022.

- ^Hrdá, S.; Votýpka, J.; Kodym, P.; Flegr, J. (August 2000). "Transient nature ofToxoplasma gondii-induced behavioral changes in mice ".The Journal of Parasitology.86(4): 657–63.doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0657:TNOTGI]2.0.CO;2.PMID10958436.S2CID2004169.

- ^Hutchison, W. M.; Aitken, P. P.; Wells, B. W. (October 1980). "ChronicToxoplasmainfections and motor performance in the mouse ".Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology.74(5): 507–10.doi:10.1080/00034983.1980.11687376.PMID7469564.

- ^Flegr, J.; Havlícek, J.; Kodym, P.; Malý, M.; Smahel, Z. (July 2002)."Increased risk of traffic accidents in subjects with latent toxoplasmosis: a retrospective case-control study".BMC Infectious Diseases.2:11.doi:10.1186/1471-2334-2-11.PMC117239.PMID12095427.

- ^Kocazeybek, B.; Oner, Y. A.; Turksoy, R.; Babur, C.; Cakan, H.; Sahip, N.; Unal, A.; Ozaslan, A.; Kilic, S.; Saribas, S.; Aslan, M.; Taylan, A.; Koc, S.; Dirican, A.; Uner, H. B.; Oz, V.; Ertekin, C.; Kucukbasmaci, O.; Torun, M. M. (May 2009). "Higher prevalence of toxoplasmosis in victims of traffic accidents suggest increased risk of traffic accident in Toxoplasma-infected inhabitants of Istanbul and its suburbs".Forensic Science International.187(1–3): 103–08.doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.03.007.PMID19356869.

- ^Torrey, E. F.; Bartko, J. J.; Lun, Z. R.; Yolken, R. H. (May 2007)."Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis".Schizophrenia Bulletin.33(3): 729–36.doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl050.PMC2526143.PMID17085743.

- ^Arling, T. A.; Yolken, R. H.; Lapidus, M.; Langenberg, P.; Dickerson, F. B.; Zimmerman, S. A.; Balis, T.; Cabassa, J. A.; Scrandis, D. A.; Tonelli, L. H.; Postolache, T. T. (December 2009). "Toxoplasma gondii antibody titers and history of suicide attempts in patients with recurrent mood disorders".The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease.197(12): 905–08.doi:10.1097/nmd.0b013e3181c29a23.PMID20010026.S2CID33395780.

- ^Ling, V. J.; Lester, D.; Mortensen, P. B.; Langenberg, P. W.; Postolache, T. T. (July 2011)."Toxoplasma gondiiseropositivity and suicide rates in women ".The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease.199(7): 440–44.doi:10.1097/nmd.0b013e318221416e.PMC3128543.PMID21716055.

- ^Johnson, S. K.; Fitza, M. A.; Lerner, D. A.; Calhoun, D. M.; Beldon, M. A.; Chan, E. T.; Johnson, P. T. (2018)."Risky business: linkingToxoplasma gondiiinfection and entrepreneurship behaviours across individuals and countries ".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.285(1883): 20180822.doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0822.PMC6083268.PMID30051870.

- ^Pearce, B. D.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; Jones, J. L. (2012)."The Relationship BetweenToxoplasma gondiiInfection and Mood Disorders in the Third National Health and Nutrition Survey ".Biological Psychiatry.72(4): 290–95.doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.003.PMC4750371.PMID22325983.

- ^Sugden, K.; Moffitt, T. E.; Pinto, L.; Poulton, R.; Williams, B. S.; Caspi, A. (2016)."IsToxoplasma gondiiInfection Related to Brain and Behavior Impairments in Humans? Evidence from a Population-representative Birth Cohort ".PLOS ONE.11(2): e0148435.Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1148435S.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148435.PMC4757034.PMID26886853.

- ^Prandovszky, E.; Gaskell, E.; Martin, H.; Dubey, J. P.; Webster, J. P.; McConkey, G. A. (2011)."The neurotropic parasite Toxoplasma gondii increases dopamine metabolism".PLOS ONE.6(9): e23866.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623866P.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023866.PMC3177840.PMID21957440.

- ^Webster, J. P.; Lamberton, P. H.; Donnelly, C. A.; Torrey, E. F. (22 April 2006)."Parasites as causative agents of human affective disorders? The impact of anti-psychotic, mood-stabilizer and anti-parasite medication on Toxoplasma gondii's ability to alter host behaviour".Proceedings. Biological Sciences.273(1589): 1023–30.doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3413.PMC1560245.PMID16627289.

- ^Gaskell, E. A.; Smith, J. E.; Pinney, J. W.; Westhead, D. R.; McConkey, G. A. (2009)."A unique dual activity amino acid hydroxylase in Toxoplasma gondii".PLOS ONE.4(3): e4801.Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4801G.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004801.PMC2653193.PMID19277211.

- ^Sangrador, Amaia; Mitchell, Alex (6 November 2014)."Protein focus: Don't blame the cat – the toxoplasmosis effect".InterPro database blog.Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2016.Retrieved27 May2019.

- ^Hari Dass, S. A.; Vyas, A. (December 2014). "Toxoplasma gondii infection reduces predator aversion in rats through epigenetic modulation in the host medial amygdala".Molecular Ecology.23(24): 6114–22.Bibcode:2014MolEc..23.6114H.doi:10.1111/mec.12888.PMID25142402.S2CID45290208.

- ^Meyer, Connor J.; Cassidy, Kira A.; Stahler, Erin E.; Brandell, Ellen E.; Anton, Colby B.; Stahler, Daniel R.; Smith, Douglas W. (24 November 2022)."Parasitic infection increases risk-taking in a social, intermediate host carnivore".Communications Biology.5(1): 1180.doi:10.1038/s42003-022-04122-0.ISSN2399-3642.PMC9691632.PMID36424436.

- ^Bracha, Shahar; et al. (29 July 2024)."Engineering Toxoplasma gondii secretion systems for intracellular delivery of multiple large therapeutic proteins to neurons".Nature Microbiology.9:2051–2072.doi:10.1038/s41564-024-01750-6.PMC11306108.

- ^Sullivan, Bill (7 August 2024)."A common parasite could one day deliver drugs to the brain − how scientists are turning Toxoplasma gondii from foe into friend".The Conversation.Archived fromthe originalon 11 August 2024.Retrieved11 August2024.

External links

[edit]- ToxoDB: TheToxoplasma gondiigenome resourceat the VEuPathDBBioinformatics Resource Center

- Parasites - Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection)by theCenters for Disease Control and Prevention

- Taking out Toxo and the Toxoplasmosis Research Institute and Centerat theUniversity of Chicago

- Anti-Toxo: AToxoplasmanews blog and list of research laboratoriesbyBill Sullivanof the School of Medicine at theIndiana University