Japanese cuisine

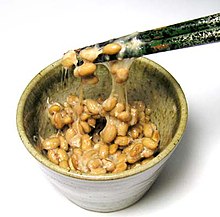

Japanese cuisineencompasses the regional and traditional foods ofJapan,which have developed through centuries of political, economic, and social changes. The traditional cuisine of Japan (Japanese:washoku) is based on rice withmiso soupand other dishes with an emphasis on seasonal ingredients. Side dishes often consist of fish, pickled vegetables, and vegetables cooked in broth. Common seafood is often grilled, but it is also sometimes served raw assashimior assushi.Seafood and vegetables are also deep-fried in a light batter, astempura.Apart from rice, a staple includes noodles, such assobaandudon.Japan also has many simmered dishes, such as fish products in broth calledoden,or beef insukiyakiandnikujaga.

Historically influenced byChinese cuisine,Japanese cuisine has also opened up to influence fromWestern cuisinesin the modern era. Dishes inspired by foreign food—in particular Chinese food—likeramenandgyōza,as well as foods likespaghetti,curryandhamburgers,have been adapted to Japanese tastes and ingredients. Traditionally, the Japaneseshunned meatas a result of adherence toBuddhism,but with the modernization of Japan in the 1880s, meat-based dishes such astonkatsuandyakinikuhave become common. Since this time, Japanese cuisine, particularly sushi and ramen, has become popular globally.

In 2011, Japan overtookFranceto become the country with the most3-starred Michelin restaurants;as of 2018[update],the capital ofTokyohas maintained the title of the city with the most 3-starred restaurants in the world.[1]In 2013, Japanese cuisine was added to theUNESCO Intangible Heritage List.[2]

History

[edit]

Rice is a staple in Japanese cuisine. Wheat and soybeans were introduced shortly after rice. All three act as staple foods in Japanese cuisine today. At the end of theKofun Periodand beginning of theAsuka Period,Buddhism became the official religion of the country. Therefore, eating meat and fish was prohibited. In 675 AD,Emperor Tenmuprohibited the eating of horses, dogs, monkeys, and chickens.[3]In the 8th and 9th centuries, many emperors continued to prohibit killing many types of animals. The number of regulated meats increased significantly, leading to the banning of all mammals except whale, which were categorized as fish.[4]During the Asuka period, chopsticks were introduced to Japan. Initially, they were only used by the nobility.[5]The general population used their hands, as utensils were quite expensive.

Due to the lack of meat products, Japanese people minimized spice utilization. Spices were rare to find at the time. Spices like pepper and garlic were only used in a minimalist amount. In the absence of meat, fish was served as the main protein, as Japan is an island nation. Fish has influenced many iconic Japanese dishes today. In the 9th century, grilled fish and sliced raw fish were widely popular.[6]Japanese people who could afford it would eat fish at every meal; others would have to make do without animal protein for many of their meals. In traditional Japanese cuisine, oil and fat are usually avoided within the cooking process, because Japanese people were trying to keep a healthy lifestyle.[6]

Preserving fish became a sensation;sushiwas originated as a means of preserving fish by fermenting it in boiled rice. Fish that are salted and then placed in rice are preserved bylactic acid fermentation,which helps prevent the proliferation of the bacteria that bring about putrefaction.[7]During the 15th century, advancement and development helped shorten the fermentation of sushi to about one to two weeks. Sushi thus became a popular snack food and main entrée, combining fish with rice. During the lateEdo period(early-19th century), sushi without fermentation was introduced. Sushi was still being consumed with and without fermentation till the 19th century when the hand-rolled and nigiri-type sushi was invented.[8]

In 1854, Japan started to enter new trade deals with Western countries.[9]WhenEmperor Meijitook power in 1868 as part of theMeiji Restoration,the government began to adopt Western customs, including the use of animal products in food.[10]The new ruler staged a New Years' feast designed to embrace the Western world and countries in 1872. The feast contained food that reflected European cuisine.[11][12]For the first time in a thousand years, people were allowed to consume meat in public, and the general population started to include meat in their regular diets.[13]

Culture

[edit]Terminology

[edit]

The wordwashoku(Hòa thực)is now the common word for traditional Japanese cooking. The termkappō(Cát phanh,lit. "cutting and boiling (meats)" )is synonymous with "cooking", but became a reference to mostly Japanese cooking, or restaurants, and was much used in theMeijiandTaishōeras.[14][15]It has come to connote a certain standard, perhaps even of the highest caliber, a restaurant with the most highly trained chefs.[16]However,kappōis generally seen as an eating establishment which is slightly more casual or informal compared to thekaiseki.[17]

Thekaiseki(Hoài thạch,lit. "warming stone" )is tied with the Japanesetea ceremony.[18]Thekaisekiis considered a (simplified) form ofhonzen-ryōri(Bổn thiện liêu lý,lit. "main tray cooking" ),[19]which was formal banquet dining where several trays of food were served.[20]Thehomophonetermkaiseki ryōri(Hội tịch liêu lý,lit. "gathering + seating" )originally referred to a gathering of composers ofhaikuorrenga,and the simplified version of thehonzendishes served at the poem parties becamekaiseki ryōri.[21]However, the meaning ofkaiseki ryōridegenerated to become just another term for a sumptuous carousing banquet, orshuen(Tửu yến).[22]

Traditional table settings

[edit]The traditional Japanesetable settinghas varied considerably over the centuries, depending primarily on the type of table common during a given era. Before the 19th century, small individual box tables (hakozen,Tương thiện ) or flat floor trays were set before each diner. Larger low tables (chabudai,ちゃぶ đài ) that accommodated entire families were gaining popularity by the beginning of the 20th century, but these gave way to Western-style dining tables and chairs by the end of the 20th century.

The traditional Japanese table setting is to place a bowl of rice on the diner’s left and to place a bowl of miso soup on the diner’s right side at the table. Behind these, eachokazuis served on its own individual plate. Based on the standard threeokazuformula, behind the rice and soup are three flat plates to hold the threeokazu;one to far back left, one at far back right, and one in the center. Pickled vegetables are often served on the side but are not counted as part of the threeokazu.Chopsticksare generally placed at the very front of the tray near the diner with pointed ends facing left and supported by achopstick rest,orhashioki.[23]

Dining etiquette

[edit]| Part ofa serieson the |

| Culture of Japan |

|---|

|

Many restaurants and homes in Japan are equipped with Western-style chairs and tables. However, traditional Japanese low tables and cushions, usually found ontatamifloors, are also very common. Tatami mats, which are made of straw, can be easily damaged and are hard to clean, thus shoes or any type of footwear are always taken off when stepping on tatami floors.[24]

When dining in a traditional tatami room, sitting upright on the floor is common. In a casual setting, men usually sit with their feet crossed and women sit with both legs to one side. Only men are supposed to sit cross-legged. The formal way of sitting for both sexes is a kneeling style known asseiza.To sit in aseizaposition, one kneels on the floor with legs folded under the thighs and the buttocks resting on the heels.[24]

When dining out in a restaurant, the customers are guided to their seats by the host. The honored or eldest guest will usually be seated at the center of the table farthest from the entrance. In the home, the most important guest is also seated farthest away from the entrance. If there is atokonoma,or alcove, in the room, the guest is seated in front of it. The host sits next to or closest to the entrance.[25]

In Japan, it is customary to sayitadakimasu( "I [humbly] receive" ) before starting to eat a meal.[26]When sayingitadakimasu,both hands are put together in front of the chest or on the lap.Itadakimasuis preceded by complimenting the appearance of food. Another customary and important etiquette is to saygo-chisō-sama deshita( "It was a feast" ) to the host after the meal and the restaurant staff when leaving.[27]

Traditional cuisine

[edit]Japanese cuisine is based on combining thestaple food,which is steamedwhite riceorgohan(Ngự phạn),with one or moreokazu,"main" or "side" dishes. This may be accompanied by a clear or miso soup andtsukemono(pickles). The phraseichijū-sansai(Nhất trấp tam thái,"one soup, three sides" )refers to the makeup of a typical meal served but has roots in classickaiseki,honzen,andyūshokucuisine. The term is also used to describe the first course served in standardkaisekicuisine nowadays.[22]

The origin of Japanese "one soup, three sides" cuisine is a dietary style called Ichiju-Issai ( nhất trấp nhất thái, "one soup, one dish" ),[28]tracing back to the Five Great Zen Temples of the 12-century Kamakura period (Kamakura Gozan), developed as a form of meal that emphasized frugality and simplicity.

Rice is served in its own small bowl (chawan), and each main course item is placed on its own small plate (sara) or bowl (hachi) for each individual portion. This is done even in Japanese homes. This contrasts with Western-style home dinners in which each individual takes helpings from large serving dishes of food placed in the middle of the dining table. Japanese style traditionally abhors different flavored dishes touching each other on a single plate, so different dishes are given their own individual plates as mentioned or are partitioned using, for example, leaves. Placing main dishes on top of rice, thereby "soiling" it, is also frowned upon by traditional etiquette.[29]

Although this tradition of not placing other foods on rice originated from classical Chinese dining formalities, especially after the adoption of Buddhist tea ceremonies; it became most popular and common during and after theKamakura period,such as in thekaiseki.Although present-day Chinese cuisine has abandoned this practice, Japanese cuisine retains it. One exception is the populardonburi,in which toppings are directly served on rice.

The small rice bowl(Trà oản,chawan),literally "tea bowl", doubles as a word for the large tea bowls in tea ceremonies. Thus in common speech, the drinking cup is referred to asyunomi-jawanoryunomifor the purpose of distinction. Among the nobility, each course of a full-course Japanese meal would be brought on serving napkins calledzen(Thiện),which were originally platformed trays or small dining tables. In the modern age,faldstooltrays or stackup-type legged trays may still be seen used inzashiki,i.e.tatami-mat rooms, for large banquets or at aryokantype inn. Some restaurants might use the suffix-zen(Thiện)as a more sophisticated thoughdatedsynonym to the more familiarteishoku(Định thực),since the latter basically is a term for acombo mealserved at ataishū-shokudō,akin to adiner.[30]Teishokumeans a meal of fixed menu (for example, grilled fish with rice and soup), a dinnerà prix fixe[31]served atshokudō(Thực đường,"dining hall" )orryōriten(Liêu lý điếm,"restaurant" ),which is somewhat vague (shokudōcan mean a diner-type restaurant or a corporate lunch hall); writer on Japanese popular culture Ishikawa Hiroyoshi[32]defines it as fare served atteishokudining halls(Định thực thực đường,teishoku-shokudō),and comparable diner-like establishments.

Seasonality

[edit]

Emphasis is placed onseasonality of foodorshun(Tuần),[33][34]and dishes are designed to herald the arrival of the four seasons or calendar months.

Seasonality means taking advantage of the "fruit of the mountains"(Sơn の hạnh,yama no sachi,alt. "bounty of the mountains" )(for example,bamboo shootsin spring,chestnutsin the autumn) as well as the "fruit of the sea"(Hải の hạnh,umi no sachi,alt. "bounty of the sea" )as they come into season. Thus the first catch ofskipjacktunas(Sơ 鰹,hatsu-gatsuo)that arrives with theKuroshio Currenthas traditionally been greatly prized.[35]

If something becomes available rather earlier than what is usual for the item in question, the first crop or early catch is calledhashiri.[36]

Use of tree leaves and branches as decor is also characteristic of Japanese cuisine. Maple leaves are often floated on water to exude coolness orryō(Lương);sprigs ofnandinaare popularly used. Theharan(Aspidistra) and sasa bamboo leaves were often cut into shapes and placed underneath or used as separators.[37]

UNESCO recognition

[edit]In February 2012, theAgency for Cultural Affairsrecommended that 'Washoku: Traditional Dietary Cultures of the Japanese' be added to theUNESCORepresentative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[38]On December 4, 2013, "Washoku, traditional dietary cultures [sic] of the Japanese, notably for the celebration of New Year "was added to UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage, bringing the number of Japanese assets listed on UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage list to 22.[39][40]

Traditional ingredients

[edit]A characteristic of traditional Japanese food is the sparing use ofred meat,oils and fats, and dairy products.[41]Use of ingredients such assoy sauce,miso,andumeboshitends to result in dishes with high salt content, though there are low-sodium versions of these available.

Meat consumption

[edit]

As Japan is anisland nationsurrounded by an ocean, its people have always taken advantage of the abundant seafood supply.[33]It is the opinion of some food scholars that the Japanese diet always relied mainly on "grains with vegetables or seaweeds as main, with poultry secondary, andred meatin slight amounts "even before the advent of Buddhism which placed an even stronger taboo.[33]The eating of "four-legged creatures"(Tứ túc,yotsuashi)was spoken of as taboo,[42]unclean or something to be avoided by personal choice through theEdo period.[43]The consumption ofwhaleandterrapinmeat were not forbidden under this definition. Despite this, the consumption of red meat did not completely disappear in Japan. Eating wild game—as opposed to domesticated livestock—was tolerated; in particular, trappedharewas counted using themeasure wordwa(Vũ),a term normally reserved for birds.

In 1872 of the Meiji restoration, as part of the opening up of Japan to Western influence,Emperor Meijilifted the ban on the consumption ofred meat.[44]The removal of the ban encountered resistance and in one notable response, ten monks attempted to break into the Imperial Palace. The monks asserted that due to foreign influence, large numbers of Japanese had begun eating meat and that this was "destroying the soul of the Japanese people." Several of the monks were killed during the break-in attempt, and the remainder were arrested.[44][13]On the other hand, the consumption of meat was accepted by the common people.Gyūnabe(beef hot pot), the prototype ofsukiyaki,became the rage of the time. Western restaurants moved in, and some of them changed their form toYōshoku.

Vegetable consumption has dwindled while processed foods have become more prominent in Japanese households due to the rising costs of general foodstuffs.[45]Nonetheless, Kyoto vegetables, orKyoyasai,are rising in popularity and different varieties of Kyoto vegetables are being revived.[46]

Cooking oil

[edit]Generally speaking, traditional Japanese cuisine is prepared with little cooking oil. A major exception is thedeep-fryingof foods. This cooking method was introduced during theEdo perioddue to influence from Western (formerly callednanban-ryōri(Nam man liêu lý)) and Chinese cuisine,[47]and became commonplace with the availability of cooking oil due to increased productivity.[47]Dishes such astempura,aburaage,andsatsuma age[47]are now part of established traditional Japanese cuisine. Words such astempuraorhiryōzu(synonymous withganmodoki) are said to be of Portuguese origin.

Also, certain rustic sorts of traditional Japanese foods such askinpira,hijiki,andkiriboshidaikon usually involvestir-fryingin oil before stewing in soy sauce. Some standardosōzaiorobanzaidishes feature stir-fried Japanese greens with eitherageorchirimen-jako,dried sardines.

Seasonings

[edit]

Traditional Japanese food is typically seasoned with a combination ofdashi,soy sauce,sakeandmirin,vinegar, sugar, and salt. A modest number of herbs and spices may be used during cooking as a hint or accent, or as a means of neutralizing fishy or gamy odors present. Examples of such spices includeginger,perillaandtakanotsume(Ưng の trảo)red pepper.[48]

Intense condiments such aswasabior Japanesemustardare provided as condiments to raw fish, due to their effect on the mucous membrane which paralyze the sense of smell, particularly from fish odors.[49]A sprig ofmitsubaor a piece ofyuzurind floated on soups are calledukimi.Mincedshisoleaves andmyogaoften serve asyakumi,a type of condiment paired withtatakiofkatsuoorsoba.Shichimiis also a very popular spice mixture often added to soups, noodles and rice cakes. Shichimi is a chilli-based spice mix which contains seven spices: chilli, sansho, orange peel, black sesame, white sesame, hemp, ginger, and nori.[50]

Garnishes

[edit]Once a main dish has been cooked, spices such as minced ginger and various pungent herbs may be added as a garnish, calledtsuma.Finally, a dish may be garnished with minced seaweed in the form of crumplednorior flakes ofaonori.[citation needed]

Inedible garnishes are featured in dishes to reflect a holiday or the season. Generally these include inedible leaves, flowers native to Japan or with a long history of being grown in the country, as well as their artificial counterparts.[51]

Salads

[edit]

Theo-hitashiorhitashi-mono(おひたし)[31]is boiled green-leaf vegetables bunched and cut to size, steeped indashibroth,[52][53]eaten with dashes of soy sauce. Another item issunomono(Tạc の vật,"vinegar item" ),which could be made withwakameseaweed,[54]or be something like akōhakunamasu(Hồng bạch なます,"red white namasu" )[55]made from thin toothpick slices of daikon and carrot. The so-called vinegar that is blended with the ingredient here is oftensanbaizu(Tam bôi tạc,"three cupful/spoonful vinegar" )[54]which is a blend of vinegar, mirin, and soy sauce. Atosazu(Thổ tá tạc,"Tosavinegar ")adds katsuo dashi to this.

Anaemono(Hòa え vật)is another group of items, describable as a sort of "tossed salad" or "dressed" (thoughaemonoalso includes thin strips of squid or fish sashimi (itozukuri) etc. similarly prepared). One type isgoma-ae(Hồ ma hòa え)[56]where usually vegetables such as green beans are tossed with white or blacksesameseeds ground in asuribachimortar bowl, flavored additionally with sugar and soy sauce.Shira-ae(Bạch hòa え)addstofu(bean curd) in the mix.[56]Anaemonois tossed with vinegar-white miso mix and useswakegi[56]scallionandbaka-gai(バカガイ / mã lộc bối,atrough shell,Mactra chinensis)as standard.

Rice

[edit]

Rice has historically been the staple food of the Japanese people. Its fundamental importance is evident from the fact that the word for cooked rice,gohanormeshi,also stands for a "meal".[57]While rice has an ancient history of cultivation in Japan, its use as a staple has not been universal. Notably, in northern areas (northern Honshū and Hokkaidō), other grains such as wheat were more common into the 19th century.

In most of Japan, rice used to be consumed for almost every meal, and although a 2007 survey showed that 70% of Japanese still eat it once or twice a day, its popularity is now declining. In the 20th century there has been a shift in dietary habits, with an increasing number of people choosing wheat-based products (such as bread and noodles) over rice.[58]

Japanese rice is short-grained and becomes sticky when cooked. Most rice is sold ashakumai( bạch mễ, "white rice" ), with the outer portion of the grains ( khang,nuka) polished away. Unpolishedbrown rice( huyền mễ,genmai) is considered less desirable, but its popularity has been increasing.[58]

Noodles

[edit]

Japanese noodles often substitute for a rice-based meal.Soba(thin, grayish-brown noodles containingbuckwheatflour) andudon(thick wheat noodles) are the main traditional noodles, while ramen is a modern import and now very popular. There are also other, less common noodles, such assomen(thin, white noodles containing wheat flour).

Japanese noodles, such as soba and udon, are eaten as a standalone, and usually not with a side dish, in terms of general custom. It may have toppings, but they are calledgu(Cụ).The fried battered shrimp tempura sitting in a bowl of tempura-soba would be referred to as "the shrimp" or "the tempura", and not so much be referred to as a topping (gu). The identical toppings, if served as a dish to be eaten with plain white rice could be calledokazu,so these terms are context-sensitive. Some noodle dishes derive their name from Japanese folklore, such askitsuneandtanuki,reflecting dishes in which the noodles can be changed, but the broth and garnishes correspond to their respective legend.[59]

Hot noodles are usually served in a bowl already steeped in their broth and are calledkakesobaorkakeudon.Cold soba arrive unseasoned and heaped atop azaruorseiro,and are picked up with a chopstick and dunked in their dipping sauce. The broth can consist of many ingredients but is generally based on dashi; the sauce, called tsuyu, is usually more concentrated and made from soy sauce, dashi and mirin, sake or both.

In the simple form,yakumi(condiments and spices) such asshichimi,nori, finely chopped scallions, wasabi, etc. are added to the noodles, besides the broth/dip sauce.

Udon may also be eaten inkama-agestyle, piping hot straight out of the boiling pot, and eaten with plain soy sauce and sometimes with raw egg also.

Japanese noodles are traditionally eaten by bringing the bowl close to the mouth, and sucking in the noodles with the aid ofchopsticks.The resulting loud slurping noise is considered normal in Japan, although in the 2010s concerns began to be voiced about the slurping being offensive to others, especially tourists. The wordnuuhara(ヌーハラ, from "nuudoru harasumento", noodle harassment) was coined to describe this.[60]

Sweets

[edit]

Traditional Japanese sweets are known aswagashi.Ingredients such asred bean pasteandmochiare used. More modern-day tastes includesgreen tea ice cream,a very popular flavor. Almost all manufacturers produce a version of it.Kakigōriis ashaved icedessert flavored with syrup or condensed milk. It is usually sold and eaten at summer festivals. A dessert very popular amongst children in Japan isdorayaki.They are sweetpancakesfilled with a sweet red bean paste. They are mostly eaten at room temperature but are also considered very delicious hot.

Drinks

[edit]Tea

[edit]Green teamay be served with most Japanese dishes. It is produced in Japan and prepared in various forms such asmatcha,the tea used in theJapanese tea ceremony.[61]

Beer

[edit]

Beer production started in Japan in the 1860s. The most commonly consumed beers in Japan are pale-coloured lightlagers,with an alcohol strength of around 5.0% ABV. Lager beers are the most commonly producedbeer stylein Japan, but beer-like beverages, made with lower levels of malts calledHapposhu( phát phao tửu, literally, "bubbly alcohol" ) or non-malt Happousei ( phát phao tính, literally "effervescence" ) have captured a large part of the market as tax is substantially lower on these products. Beer and its varieties have a market share of almost 2/3 of alcoholic beverages.

Small localmicrobrewerieshave also gained increasing popularity since the 1990s, supplying distinct tasting beers in a variety of styles that seek to match the emphasis on craftsmanship, quality, and ingredient provenance often associated with Japanese food.

Sake

[edit]

Sakeis a brewed rice beverage that typically contains 15–17%alcoholand is made by multiplefermentationof rice. At traditional formal meals, it is considered an equivalent to rice and is not simultaneously taken with other rice-based dishes, although this notion is typically no longer applied to modern, refined, premium ( "ginjo" ) sake, which bear little resemblance to the sakes of even 100 years ago. Side dishes for sake are particularly calledsakanaorotsumami.

Sake is brewed in a highly labor-intensive process more similar to beer production than winemaking, hence, the common description of sake as rice "wine" is misleading. Sake is made with, by legal definition, strictly just four ingredients:special rice,water,koji,and specialyeast.

As of 2014, Japan has some 1500 registered breweries,[62]which produce thousands of different sakes. Sake characteristics and flavor profiles vary with regionality, ingredients, and the styles (maintained by brewmaster guilds) that brewery leaders want to produce.

Sake flavor profiles lend extremely well to pairing with a wide variety of cuisines, including non-Japanese cuisines.

Shōchū

[edit]Shōchūis adistilled spiritthat is typically made frombarley,sweet potato,buckwheat,or rice.Shōchūis produced everywhere in Japan, but its production started inKyushu.[63]

Whisky

[edit]

Japanese whiskybegan commercial production in the early 20th century, and is now extremely popular, primarily consumed inhighballs(ハイボール,haibōru).It is produced in the Scottish style, with malt whisky produced since the 1980s, and has won top international awards since the 2000s.

Wine

[edit]Adomestic wine productionexists since the 1860s yet most wine is imported. The total market share of wine on alcoholic beverages is about 3%.[64]

Specialty food

[edit]

Wagyuis the collective name for the four principalJapanese breedsofbeef cattle.All wagyū cattle derive fromcross-breedingin the early twentieth century of native Japanese cattle with imported stock, mostly from Europe. In several areas of Japan, Wagyu beef is shipped carrying area names. Some examples areMatsusaka beef,Kobe beef,Yonezawa beef,Ōmi beef,andSandabeef. In recent years, Wagyu beef has increased in fat percentage due to a decrease in grazing and an increase in using feed, resulting in larger, fattier cattle.

Specialty eggs – compared to ordinary eggs, eggs produced with special feed and poultry-raising.

TheYubari King(Tịch trương メロン,Yūbari Meron,Yūbari melon)is acantaloupecultivarfarmed ingreenhousesinYūbari, Hokkaido,a small city close toSapporo

Squareorcube watermelonsarewatermelonsgrown into the shape of acube.Cube watermelons are commonly sold in Japan, where they are essentially ornamental and are often very expensive, with prices as high asUS$200.

Cooking techniques

[edit]Different cooking techniques are applied to each of the threeokazu;they may be raw (sashimi),grilled,simmered(sometimes calledboiled),steamed,deep-fried,vinegared, ordressed.

Dishes

[edit]

Inichijū-sansai(Nhất trấp tam thái,"one soup, three sides"),the wordsai(Thái)has the basic meaning of "vegetable", but secondarily means any accompanying dish (whether it uses fish or meat),[65]with the more familiar combined formsōzai(Tổng thái),[65]which is a term for any side dish, such as the vast selections sold at Japanese supermarkets ordepachikas.[66]

It figures in the Japanese word for appetizer,zensai(Tiền thái);main dish,shusai(Chủ thái);orsōzai(Tổng thái)(formal synonym forokazu), but the latter is considered somewhat of a ladies' term ornyōbō kotoba.[67]

Below are listed some of the most common categories for prepared food:

- Yakimono( thiêu き vật ), grilled and pan-fried dishes

- Nimono( chử vật ), stewed/simmered/cooked/boiled dishes

- Itamemono( sao め vật ), stir-fried dishes

- Mushimono( chưng し vật ), steamed dishes

- Agemono( dương げ vật ), deep-fried dishes

- Sashimi( thứ thân ), sliced raw fish

- Suimono( hấp い vật ) andshirumono( trấp vật ), soups

- Tsukemono( tí け vật ), pickled/salted vegetables

- Aemono( hòa え vật ), dishes dressed with various kinds of sauce

- Sunomono( tạc の vật ), vinegared dishes

- Chinmi( trân vị ), delicacies[31]

Classification

[edit]Kaiseki

[edit]Kaiseki,closely associated with tea ceremony (chanoyu), is a high form of hospitality through cuisine. The style is minimalist, extolling the aesthetics ofwabi-sabi.Like the tea ceremony, appreciation of the diningware and vessels is part of the experience. In the modern standard form, the first course consists ofichijū-sansai(one soup, three dishes), followed by the serving of sake accompanied by dish(es) plated on a square wooden bordered tray of sorts calledhassun(Bát thốn).Sometimes another element calledshiizakana(Cường hào)is served to complement the sake, for guests who are heavier drinkers.

Vegetarian

[edit]

Strictly vegetarian food is rare since even vegetable dishes are flavored with the ubiquitous dashi stock, usually made withkatsuobushi(driedskipjack tunaflakes), and are thereforepescetarianmore often than carnivorous. An exception isshōjin-ryōri( tinh tiến liêu lý ), vegetarian dishes developed by Buddhist monks. However, the advertisedshōjin-ryōriat public eating places includes some non-vegetarian elements. Vegetarianism,fucha-ryōri(Phổ trà liêu lý)was introduced from China by theŌbakusect (a sub-sect of Zen Buddhism), and which some sources still regard as part of "Japanese cuisine".[33]The sect in Japan was founded by the priestIngen(d. 1673), and is headquartered inUji, Kyoto.The Japanese name for thecommon green beantakes after this priest who allegedly introduced the New World crop via China. One aspect of the fucha-ryōri practiced at the temple is the wealth ofmodoki-ryōri(もどき liêu lý,"mock foods"),one example being mock-eel, made from strainedtofu,withnoriseaweed used expertly to mimic the black skin.[68]The secret ingredient used is gratedgobō(burdock) roots.[69][70]

Masakazu Tada, Honorary Vice-President of theInternational Vegetarian Unionfor 25 years from 1960, stated that "Japan was vegetarian for 1,000 years". The taboo against eating meat was lifted in 1872 by the Meiji Emperor as part of an effort towards westernizing Japan.[13]British journalistJ. W. Robertson Scottreported in the 1920s that the society was still 90% vegetarian, and 50–60% of the population ate fish only on festive occasions, probably due to poverty more than for any other reason.

Regional cuisine

[edit]Japanese cuisine offers a vast array of regional specialties known askyōdo-ryōri( hương thổ liêu lý ), many of them originating from dishes prepared using traditional recipes with local ingredients. Foods from theKantō regiontaste very strong. For example, thedashi-based broth for servingudonnoodles is heavy on darksoy sauce,similar tosobabroth. On the other hand,Kansai regionfoods are lightly seasoned, with clear udon noodles.[71]made with light soy sauce.[23]

Dishes for special occasions

[edit]

In Japanese tradition, some dishes are strongly tied to a festival or event. These dishes include:

| Image | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Botamochi | a sticky rice dumpling with sweet azuki paste served in spring, while a similar sweetOhagiis served in autumn. |

|

Chimaki | steamed sweet rice cake.Tango no sekkuandGion Festival. |

|

Hamo | a type of fish, ofteneel[72]andsōmen:Gion Festival. |

|

Osechi | New Year. |

|

Sekihan | red rice, which is served for any celebratory occasion. It is usually sticky rice cooked with azuki, or red bean, which gives the rice its distinctive red colour.[73] |

|

Soba:[74] | New Year's Eve. This is calledtoshi koshi soba(literally "year crossing soba" ). |

|

Chirashizushi,Ushiojiru (clear soup of clams) andamazake | Hinamatsuri. |

In some regions, on every first and fifteenth day of the month, people eat a mixture of rice and azuki (azuki meshi( tiểu đậu phạn ); seeSekihan).

Imported and adapted foods

[edit]Japan has a long history of importing food from other countries, some of which are now part of Japan's most popular cuisine.Ramenis considered an important part to their culinary history, to the extent where in survey of 2,000 Tokyo residents,instant ramencame up many times as a product they thought was an outstanding Japanese invention.[75]Believed to have originated in China, ramen became popular in Japan after theSecond Sino-Japanese war(1937–1945), when many Chinese students were displaced to Japan.[76]

Curry is another popular imported dish and is ranked near the top of nearly all Japanese surveys for favorite foods. The average Japanese person eats curry at least once a week.[78]The origins of curry, as well many other foreign imports such aspanor bread, are linked to the emergence ofyōshoku,or western cuisine.Yōshokucan be traced as far back as the lateMuromachi period(1336–1573) during a culinary revolution callednamban ryori( nam man liêu lý ), which means "Southern barbarian cooking", as it is rooted in European cuisine.[76]This cuisine style was first seen inNagasaki,which served as the point of contact between Europe and Japan at that point in time. Food items such as potatoes, corn, dairy products, as well as the hard candykompeito( kim bình đường ), spread during this time.[76]This cuisine became popular in theMeiji period,which is considered by many historians to be when Japan first opened itself to the outside world.

Bread was not a traditional food in Japan, butshokupan,orJapanese milk bread,was developed and came into broad use after the American response to post-World War II Japaneserice shortagesincludedreliefshipments ofwheat.[79]

Today, many of these imported items still hold a heavy presence in Japan.[citation needed]

Japan today abounds with home-grown, loosely Western-style food. Many of these were invented in the wake of the 1868Meiji Restorationand the end ofnational seclusion,when the sudden influx of foreign (in particular, Western) culture led to many restaurants serving Western food, known asyōshoku( dương thực ), a shortened form ofseiyōshoku( tây dương thực, "Western cuisine" ), opening up in cities. Restaurants that serve these foods are calledyōshokuya( dương thực ốc, "Western cuisine restaurants" ).[80]

Manyyōshokuitems from that time have been adapted to a degree that they are now considered Japanese and are an integral part of any Japanese family menu. Many are served alongside rice and miso soup, and eaten with chopsticks. Yet, due to their origins these are still categorized asyōshokuas opposed to the more traditionalwashoku( hòa thực, "Japanese cuisine" ).[81]

Chūka ryōri – Japanese Chinese cuisine

[edit]Chinese cuisine is one of the oldest and most common foreign cuisines in Japan, predating the introduction of Western food dishes into the country. Many Chinese dishes have been altered to suit Japanese palates in a type of cuisine known as "chuka ryori". Iconic dishes of chuka ryori includeramen,gyoza,andchukaman.

Okonomiyaki

[edit]

Okonomiyaki is a savoury pancake containing a variety of ingredients in a wheat-flour-based batter.[82]

Tonkatsu

[edit]

Tonkatsu is a breaded, deep-fried pork cutlet. It is frequently served withtonkatsu sauce.[83]

Curry

[edit]Currywas introduced byAnglo-Indian officers of theRoyal NavyfromIndiawho brought curry powder to Japan in theMeiji period.[84]TheImperial Japanese Navyadopted curry to preventberiberi.Overtime it was reinvented and adapted to suit Japanese tastes that it became uniquely Japanese.[84]It is consumed so much that it is considered anational dish.[77]Many recipes are on the menu of theJMSDF.[85]A variety of vegetables and meats are used to makeJapanese curry,usually vegetables like onions, carrots, and potatoes. The types of meat used are beef, pork, and chicken. A popular dish isKatsu-karēwhich is abreaded deep-fried cutlet(tonkatsu;usually pork or chicken) with Japanese curry sauce.[86]Japanese currycan be found in foods such as curryudon,curry bread,andkatsukarē,tonkatsuserved with curry. It's very commonly made with rice beside the curry on the dish called "curry"(カレー,karē).This can be eaten during dinner.

Wafū burgers (Japanese-style burgers)

[edit]Hamburgerchains active in Japan includeMcDonald's,Burger King,First Kitchen,LotteriaandMOS Burger.Many chains developed uniquely Japanese versions of American fast food such as theteriyakiburger,kinpira(sauté) rice burger, fried shrimp burgers, and green teamilkshakes.[87]

Italian

[edit]High-class Japanese chefs have preserved many Italian seafood dishes that are forgotten in other countries. These include pasta withprawns,lobster(a specialty known in Italy as pasta all'aragosta),crab(an Italian specialty; in Japan it is served with a different species of crab), and pasta withsea urchinsauce (sea urchin pasta being a specialty of thePuglia region).[88]

Outside Japan

[edit]

Many countries have imported portions of Japanese cuisine. Some may adhere to the traditional preparations of the cuisines, but in some cultures the dishes have been adapted to fit the palate of the local populace. In 1970s sushi travelled from Japan to Canada and the United States, it was modified to suit the American palate, and re-entered the Japanese market as "American Sushi".[89]An example of this phenomenon is theCalifornia roll,which was created in North America in the 1970s, rose in popularity across the United States through the 1980s, and thus sparked Japanese food's – more precisely, sushi's – global popularity.

In 2014, Japanese Restaurant Organization has selected potential countries where Japanese food is becoming increasingly popular, and conducted research concerning the Japanese restaurants abroad. These key nations or region areTaiwan,Hong Kong, China, Singapore,ThailandandIndonesia.[90]This was meant as an effort to promote Japanese cuisine and to expand the market of Japanese ingredients, products and foodstuffs. Numbers of Japanese foodstuff and seasoning brands such asAjinomoto,Kikkoman,NissinandKewpiemayonnaise, are establishing production base in other Asian countries, such as China, Thailand and Indonesia.

Australia

[edit]Japanese cuisine is very popular in Australia, and Australians are becoming increasingly familiar with traditional Japanese foods.[91]Restaurants serving Japanese cuisine feature prominently in popular rankings, including Gourmet Traveller and The Good Food Guide.[92]

Sushi in particular has been described as being "as popular as sandwiches", particularly in large cities like Melbourne, Sydney, or Brisbane.[93]As such, sushi bars are a mainstay in shopping centre food courts, and are extremely common in cities and towns all over the country.[93]

Brazil

[edit]In Brazil, Japanese food is widespread due to the largeJapanese-Brazilianpopulation living in the country, which represents the largest Japanese community living outside Japan. Over the past years, many restaurant chains such asKoni Store[94]have opened, selling typical dishes such as the populartemaki.Yakisoba,which is readily available in all supermarkets, and often included in non-Japanese restaurant menus.[95]

Canada

[edit]In Canada, Japanese cuisine has become quite popular.Sushi,sashimi,and instant ramen are highly popular at opposite ends of the income scale, with instant ramen being a common low-budget meal. Sushi and sashimi takeout began inVancouverandToronto,and is now common throughout Canada. The largest supermarket chains all carry basic sushi and sashimi, and Japanese ingredients and instant ramen are readily available in most supermarkets. Most mid-sized mall food courts feature fast-food teppan cooking.Izakayarestaurants have surged in popularity. Higher-end ramen restaurants (as opposed to instant ramen noodles of variable quality) are increasingly common.[96]

Indonesia

[edit]

In theASEANregion, Indonesia is the second largest market for Japanese food, after Thailand. Japanese cuisine has been increasingly popular as a result of the growing Indonesian middle-class expecting higher quality foods.[90]This has also contributed to the fact that Indonesia has large numbers ofJapanese expatriates.The main concern is the issue of many traditional Japanese recipes not beinghalal.As aMuslimmajority country, Indonesians expect that Japanese foods served there are halal according to Islamic dietary law, which means no pork or alcohol are allowed. Japanese restaurants in Indonesia often offer a set menu which includes rice served with an array of Japanese favourites in a single setting. A set menu might include a choice of yakiniku or sukiyaki, including a sample of sushi, tempura, gyoza and miso soup. Authentic Japanese styleizakayaandramenshops can be found in the Little Tokyo (Melawai) area inBlok M,South Jakarta, serving both Japanese expats and local clienteles.[98]Today, Japanese restaurants can be found in most major Indonesian cities, with a high concentration inGreater Jakartaarea,Bandung,SurabayaandBali.

In some cases, Japanese cuisine in Indonesia is often altered to suit Indonesian taste.Hoka Hoka Bentoin particular is an Indonesian-owned Japanese fast food restaurant chain that caters to the Indonesian clientele. As a result, the foods served there have been adapted to suit Indonesians' taste. Examples of the change include stronger flavours compared to the authentic subtle Japanese taste, the preference for fried food, as well as the addition ofsambalto cater to the Indonesians' preference for hot and spicy food.

Japanese food popularity also has penetratedstreet food culture,as modestWarjeporWarungJepang(Japanese food stall) offer Japanese food such as tempura, okonomiyaki and takoyaki, at moderately low prices.[99]Today, okonomiyaki and takoyaki are popular street fare in Jakarta and other Indonesian cities.[100][101]This is also pushed further by the Japanese convenience stores operating in Indonesia, such as7-ElevenandLawsonoffering Japanese favourites such asoden,chicken katsu (deep-fried chicken cutlet), chicken teriyaki andonigiri.[102]

Some chefs in Indonesian sushi establishments have created a Japanese-Indonesian fusion cuisine, such as krakatau roll,gado-gadoroll,rendangroll andgulairamen.[103]The idea of fusion cuisine melding spicy IndonesianPadangand Japanese cuisine was combined because both cuisine traditions are well-liked by Indonesians.[104]Nevertheless, some of these Japanese eating establishments might strive to serve authentic Japanese cuisine abroad.[105]Numbers of Japanese chain restaurants has established their business in Indonesia, such asYoshinoyagyūdon restaurant chain,[106]Gyu-Kakuyakiniku restaurant chain andAjisen Ramenrestaurant chain.

Mexico

[edit]InMexico,certain Japanese restaurants have created what is known as "sushi Mexicano", in which spicy sauces and ingredients accompany the dish or are integrated in sushi rolls. Thehabaneroandserranochiles have become nearly standard and are referred to as chiles toreados, as they are fried, diced and tossed over a dish upon request.

Philippines

[edit]In thePhilippines,Japanese cuisine is also popular among the local population.[107]The Philippines have been exposed to the influences from the Japanese,IndianandChinese.[108]The cities ofDavaoandMetro Manilaprobably have the most Japanese influence in the country.[109][110]The popular dining spots for Japanese nationals are located inMakati,which is called as "Little Tokyo", a small area filled with restaurants specializing in different types of Japanese food. Some of the best Japanese no-frills restaurants in the Philippines can be found in Makati's "Little Tokyo" area.[111]In the Philippines,Halo-halois derived from JapaneseKakigori.Halo-halo is believed to be an indigenized version of the Japanesekakigoriclass of desserts, originating from pre-warJapanese migrants into the islands. The earliest versions were composed only of cookedred beansormung beansin crushed ice with sugar and milk, a dessert known locally as "mongo-ya".Over the years, more native ingredients were added, resulting in the development of the modernhalo-halo.[112][113]Some authors specifically attribute it to the 1920s or 1930s Japanese migrants in theQuinta MarketofQuiapo,Manila, due to its proximity to the now defunctInsular Ice Plant,which was the source of the city's ice supply.[114]InCebu City,the Little Kyoto district let's you experience the feel of being inKyoto,Japanwith a statue of the recliningBuddhaoverlooking the city. The Little Kyoto district also features Japanese food stalls serving various Japanese dishes likeTakoyaki,Tempura,and various other Japanese cuisine that is enjoyed by the people of Cebu City, Philippines.[115][116]Odong,also calledpancit odong,is aVisayannoodle soupmade withodongnoodles,cannedsmoked sardines (tinapa) in tomato sauce,bottle gourd(upo),loofah(patola),chayote,ginger, garlic,red onions,and various other vegetables. It is garnished and spiced withblack pepper,scallions,toasted garlic,calamansi,orlabuyo chilis.[117][118][119][120]The dish is usually prepared as a soup, but it can also be cooked with minimal water, in which case, it is known asodong guisado.[121]

It is a common simple and cheap meal inMindanao(particularly theDavao Region) and theVisayas Islands.[122][121][123]It is almost always eaten with white rice, rarely on its own.[121]

It is named after the round flour noodles calledodongwhich are closest in texture and taste to theOkinawa soba.These noodles are characteristically sold dried into straight sticks around 6 to 8 in (15 to 20 cm) long.[123]The name is derived from theJapaneseudonnoodles, although it does not useudonnoodles or bear any resemblance toudondishes. It originates from theDavao RegionofMindanao[124]which had a large Japanese migrant community in the early 1900s.[125]Theodongnoodles were previously locally manufactured byOkinawans,but modernodongnoodles (which are distinctly yellowish) are imported fromChina.[124]Becauseodongnoodles are difficult to find in other regions, they can be substituted with other types of noodles; includingmisua,miki(egg noodles),udon,and eveninstant noodles.[119][121]

Taiwan

[edit]Japan and Taiwan have sharedclose historical and cultural relations.Dishes such as sushi, ramen, and donburi are very popular among locals. Japanese chain restaurants such as Coco Ichibanya, Ippudo, Kura Sushi, Marugame Seimen, Mister Donut, MOS Burger, Ootoya, Ramen Kagetsu Arashi, Saizeriya, Sukiya, Sushiro, Tonkatsu Shinjuku Saboten, Yayoi Ken, and Yoshinoya, can all be found in Taiwan, among others. Taiwan has adapted many Japanese food items. Tianbula ( "Taiwanese tempura" ) is actually satsuma-age and was introduced to Taiwan duringJapanese ruleby people from Kyushu, where the wordtempurais commonly used to refer to satsuma-age.[126][127][128]It is popular as a night market snack and as an ingredient for oden, hot pot and lu wei. Taiwanese versions of oden are sold locally as olen or, more recently, as guandongzhu (from Japanese Kantō-ni) in convenience stores.

Thailand

[edit]In Southeast Asia, Thailand is the largest market for Japanese food. This is partly because Thailand is a populartourist destination,having large numbers ofJapanese expatriates,as well as the local population having developed a taste for authentic Japanese cuisine. According to the Organisation that Promote Japanese Restaurants Abroad (JRO), the number of Japanese restaurants in Thailand jumped about 2.2-fold from 2007's figures to 1,676 in June 2012. InBangkok,Japanese restaurants accounts for 8.3 percent of all restaurants, following those that serveThai.[129]Numbers of Japanese chain restaurants has established their business in Thailand, such as Yoshinoya gyūdon restaurant chain, Gyu-Kakuyakinikurestaurant chain and Kourakuen ramen restaurant chain.

United Kingdom

[edit]

Japanese food Inspired restaurant chains in the UK includeWagamama,YO! Sushi,Nudo Sushi Box,Wasabi,Bone Daddies and Kokoro, often localising the food and mixing in other ingredients originating fromSoutheast AsiaandIndia.

United States

[edit]TheCalifornia rollhas been influential in sushi's global popularity; its invention often credited to a Japanese-born chef working in Los Angeles, with dates assigned to 1973, or even 1964.[130][131]The dish has been snubbed by some purist sushi chefs,[130]and also likened to the America-bornchop sueyby one scholar.[131]

As of 2015[update]the country has about 4,200 sushi restaurants.[132]It is one of the most popular styles of sushi in the US market. Japanese cuisine is an integral part of food culture in Hawaii as well as in other parts of the United States. Popular items are sushi, sashimi, and teriyaki.Kamaboko,known locally as fish cake, is a staple ofsaimin,a noodle soup that is a local favorite in Hawaii.[133]Sushi, long regarded as quite exotic in the west until the 1970s, has become a popular health food in parts of North America, Western Europe and Asia.

Two of the first Japanese restaurants in the United States were Saito and Nippon. Restaurants such as these popularized dishes such as sukiyaki and tempura, while Nippon was the first restaurant in Manhattan to have a dedicated sushi bar.[134]Nippon was also one of the first Japanese restaurants in the U.S. to grow and process their own soba[135]and responsible for creation of the now standardbeef negimayaki dish.[136]

In the U.S., theteppanyaki"iron hot plate" cooking restaurant took foothold. Such restaurants featured steak, shrimp and vegetables (includingbean sprouts), cooked in front of the customer on a "teppanyaki grill" (teppan) by a personal chef who turns cooking into performance art, twirling and juggling cutting knives like batons. The meal would be served with steamed rice and Japanese soup. This style of cooking was made popular in the U.S. whenRocky Aokifounded his popular restaurant chainBenihanain 1964.[137][138]In Japan this type of cooking is thought to be American food, but in the U.S. it is thought to be Japanese. Aoki thought this would go over better in the U.S. than traditional Japanese cuisine because he felt that Americans enjoyed "eating in exotic surroundings, but are deeply mistrustful of exotic foods".[139]

Food controversies

[edit]

Some elements of Japanese cuisine involvingeating live seafood,such asIkizukuriandOdori ebi,have received criticism overseas as a form ofanimal cruelty.[140]

Japanese cuisine is heavily dependent on seafood products. About 45 kilograms of seafood are consumed per capita annually in Japan, more than most other developed countries.[141]An aspect of environmental concern is Japanese appetite for seafood, which could contribute to the depletion of natural ocean resources. For example, Japan consumes 80% of the global supply ofblue fin tuna,a popularly sought sushi and sashimi ingredient, which could lead to its extinction due to commercialoverfishing.[142]Another environmental concern is commercialwhalingand the consumption ofwhale meat,for which Japan is the world's largest market.[143][144]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Demetriou, Danielle (October 19, 2011)."Japan relishes status as country with most three-starred Michelin restaurants".The Daily Telegraph.ISSN0307-1235.Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2022.RetrievedJanuary 15,2019.

- ^"Japanese cuisine added to Unesco 'intangible heritage' list".BBC News.December 5, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on January 7, 2021.RetrievedJune 3,2021.

- ^Rath, Eric C. (2013)."Reevaluating Rikyū: Kaiseki and the Origins of Japanese Cuisine".The Journal of Japanese Studies.39(1): 67–96.doi:10.1353/jjs.2013.0022.ISSN1549-4721.

- ^Stevens, Carolyn S. (May 2011)."Touch: Encounters with Japanese Popular Culture".Japanese Studies.31(1): 1–10.doi:10.1080/10371397.2011.559898.ISSN1037-1397.

- ^Bestor, Theodore C. (December 10, 2012)."Cuisine and identity in contemporary Japan".Routledge Handbook of Japanese Culture and Society.Routledge.doi:10.4324/9780203818459.ch22.ISBN978-0-203-81845-9.

- ^abAshkenazi, Michael; Jacob, Jeanne; Michael Ashkenazi, Michael Ashkenazi (October 11, 2013).The Essence of Japanese Cuisine(0 ed.). Routledge.doi:10.4324/9781315027487.ISBN978-1-136-81549-2.

- ^Jung, S. (2019).The Japanese Culinary Academy teaches you the fundamentals of food from the Land of the Rising Sun

- ^Avey, T. (2012).Discover the History of SushiArchivedApril 17, 2021, at theWayback Machine

- ^"The United States and the Opening to Japan, 1853".United States Office of the Historian.Archivedfrom the original on May 24, 2022.RetrievedMay 2,2024.

- ^Allen, Kristi (March 26, 2019)."Why Eating Meat Was Banned in Japan for Centuries".Atlas Obscura.Archivedfrom the original on May 18, 2021.RetrievedMay 2,2024.

- ^Hosking, Richard (2010).Food and Language: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cooking 2009.Oxford Symposium. p. 37.ISBN978-1-903018-79-8.

- ^Downer, Lesley (2001).At the Japanese Table: New and Traditional Recipes.Chronicle Books. p. 161.ISBN978-0-8118-3280-9.

- ^abcAllen, Kristi (March 26, 2019)."Why Eating Meat Was Banned in Japan for Centuries".Atlas Obscura.Archivedfrom the original on May 18, 2021.RetrievedDecember 26,2019.

- ^"Kappō かっ‐ぽう【 cát phanh 】ArchivedSeptember 30, 2024, at theWayback Machine",Kojien,4th ed., 1991.

- ^Tada, Tetsunosuke[in Japanese](1994)."Kappo"Cát phanh かつぽう.Nihon Dai-hyakka zensho.Vol. 5.Shogakukan.p. 436.ISBN9784095260013.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedOctober 16,2020.

- ^Burum, Linda (1992). "Koryori-ya, Kappo, and Robata Restaurants: Little Dishes with More Style".A Guide to Ethnic Food in Los Angeles.Harper Perennial.p. 43.ISBN9780062730381.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedOctober 16,2020.

- ^"What is Japanese Kappo cuisine?".Michelin.December 19, 2017.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedJanuary 15,2020.

- ^"Kaiseki(5) かい‐せき【 hoài thạch 】ArchivedSeptember 30, 2024, at theWayback Machine",Kojien,4th ed., 1991.

- ^Assmann, Stephanie; Rath, Eric C. (2010)."Koryori-ya, Kappo, and Robata Restaurants: Little Dishes with More Style".A Guide to Ethnic Food in Los Angeles.University of Illinois Press.p. 4.ISBN9780252077524.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedJanuary 15,2020.

- ^"Honzenryōri ほんぜん‐りょうり【 bổn thiện liêu lý 】ArchivedSeptember 30, 2024, at theWayback Machine",Kojien,4th ed., 1991.

- ^"Kaiseki(1) かい‐せき【 hội tịch 】ArchivedSeptember 30, 2024, at theWayback Machine","かいせき‐りょうり【 hội tịch liêu lý 】 "Kojien,4th ed., 1991.

- ^abYomiuri Shimbun, Osaka (2005) [2001].Zatsugaku shimbunTạp học tân văn.PHP Kenkyusho.ISBN978-4-569-64432-5.,p. 158

- ^abIntroduction to Japanese FoodArchivedDecember 21, 2016, at theWayback Machine.Retrieved January 8, 2010

- ^ab"Japan Etiquette".Etiquette Scholar.Yellowstone Publishing, LLC.Archivedfrom the original on August 29, 2021.RetrievedJanuary 16,2017.

- ^Lininger, Mike."Japan Etiquette | International Dining Etiquette | Etiquette Scholar".Etiquette Scholar.RetrievedOctober 3,2018.

- ^Ogura, Tomoko; tiểu thương bằng tử (2008)."Itadakimasu" o wasureta Nihonjin: tabekata ga migaku hinsei(Shohan ed.). Tōkyō: Asukī Media Wākusu. p. 68.ISBN9784048672870.OCLC244300317.

- ^"ごちそうさまでした in English – Japanese–English Dictionary".Glosbe.Archivedfrom the original on June 22, 2020.RetrievedJune 2,2019.

- ^Kobayashi, T."Taste of Simplicity: Japanese One-Soup One-Dish Cuisine".WAWAZA.RetrievedJuly 10,2021.

- ^Kondo, Tamami( cận đằng châu thật ) (2010).Nhật bổn の tác pháp としきたり: Tứ quý の hành sự と quan hôn táng tế, その do lai と thường thức[Nihon no saho to shikitari: shiki no gyoji to kankon sosai, sono yurai to joshiki](preview).PHP nghiên cứu sở.ISBN978-4-569-77764-1.,p. 185

- ^"Taishūshokudō たいしゅう‐しょくどう【 đại chúng thực đường 】ArchivedSeptember 30, 2024, at theWayback Machine",Kojien,4th ed., 1991.

- ^abcdKenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary,ISBN4-7674-2015-6

- ^Ishikawa, Hiroyoshi[in Japanese](1991).Taishū bunka jiten.Kōbundō. p. 516.ISBN9784335550461.

- ^abcdMotoyama, Tekishū[in Japanese](1969) [1968]. "Nihon ryōri"Nhật bổn liêu lý.Sekai hyakka jiten thế giới bách khoa sự điển.Vol. 17. Heibonsha. pp. 355–356.

- ^"A Day in the Life: Seasonal Foods"ArchivedJanuary 16, 2013, at theWayback Machine,The Japan Forum Newsletter No.September 14, 1999.

- ^Itoh, Makiko (April 26, 2013)."Katsuo, Japan's ubiquitous tuna".Japan Times.RetrievedOctober 19,2020.

- ^Hepburn (1888)dictionary "hashiri: The first fruits, or first caught fish of the season"

- ^Gordenker, Alice (January 15, 2008)."Bento grass".Japan Times.ISSN0447-5763.RetrievedJune 5,2019.

- ^"Japanese cuisine to be nominated for UNESCO world heritage list".Mainichi Daily News.February 18, 2012. Archived fromthe originalon February 19, 2012.RetrievedFebruary 19,2012.

- ^UNESCO Culture Sector – Intangible Heritage – 2003 Convention:ArchivedOctober 22, 2016, at theWayback MachineUNESCO. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^"Japanese cuisine added to UNESCO intangible heritage list".Mainichi Daily News.December 5, 2013. Archived fromthe originalon December 10, 2013.RetrievedDecember 5,2013.

- ^Ehara, Ayako (1999)."School Meals and Japan's Changing Diet".Japan Echo.26.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedOctober 18,2015.

Relatively alien to the traditional Japanese diet were meat, oil and fats, and dairy products..

. - ^Cawthorn (1997),p. 7

- ^Morimatsu, Yoshiaki; Hinonishi, Sukenori; Sakamoto, Taro (1957).Phong tục từ điển.Đông kinh đường xuất bản.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedOctober 18,2015.

Thiên võ thiên hoàng tam niên に ngưu ・ mã. Khuyển ・ viên, kê の nhục を thực べゐこと cổ cấm じてから nhục thực が diễn じ, giang hộ thời đại になっても tứ túc ・ nhị túc を thực べない gia が đa かった. もっとも dã thú の nhục は thực dụng に cung した.

- ^abWatanabe, Zenjiro."Removal of the Ban on Meat: The Meat-Eating Culture of Japan at the Beginning of Westernization"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on April 29, 2019.RetrievedDecember 26,2019.

- ^Pulvers, Roger (March 6, 2011)."Japanese families' nutritional values pay dearly for 'progress'".Japan Times.Archived fromthe originalon August 1, 2012.RetrievedMarch 22,2011.

- ^Ochiai, H. (November 25, 2014). Is it a potato or a prawn?: Kyoto farmers make a name selling strangely shaped vegetables, The Japan News by the Yomiuri Shimbun, the-japan-news.com/news/article/0001713547

- ^abcFukuta, Ajio ( phúc điền アジオ) (1999).Nihon minzoku daijiten( nhật bổn dân tục đại từ điển ).Vol. 1. Yoshikawa Kobunkan ( cát xuyên hoằng văn quán ).ISBN9784642013321.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedOctober 18,2015.,p.16 an thổ, đào sơn thời đại から giang hộ thời đại にかけて nam man liêu lý や trung quốc liêu lý の ảnh hưởng と du の sinh sản tăng đại に bạn い, du dương や thiên phu la, tố dương, tát ma huy など phó thực vật として

- ^Li, Jin-lin; Tu, Zong-cai; Zhang, Lu; Sha, Xiao-mei; Wang, Hui; Pang, Juan-juan; Tang, Ping-ping (August 1, 2016)."The effect of ginger and garlic addition during cooking on the volatile profile of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) soup".Journal of Food Science and Technology.53(8): 3253–3270.doi:10.1007/s13197-016-2301-1.ISSN0975-8402.PMC5055890.PMID27784920.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedSeptember 20,2021.

- ^Hirasa, Kenji; Takemasa, Mitsuo (June 16, 1998).Spice Science and Technology.CRC Press. pp. 76–77.ISBN978-0-585-36755-2.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedSeptember 24,2021.

- ^Today, What Way."Food in Japan is not just about Sushi – Japanese Food Adventure".What Way Today.Archived fromthe originalon June 11, 2021.RetrievedApril 20,2016.

- ^Pemberton, Robert W. (1999)."Japanese Food as Art and Symbol: Evidence from Inedible Leaf Garnishes".Petits Propos Culinaires.

- ^Andoh (2012),p. 20 "spinach steeped in broth"; p. 63 "(spinach) blanched and then marinated" in smoky broth.

- ^Shimbo (2000),p. 237: "Ohitashi literally means 'dipped item,' although the dressing is actually poured over the leaf vegetables."

- ^abShimbo (2000),p. 147 "wakame and cucumber in sanbaizu dressing (sunomono)"; p. 74 "sanbaizu" recipe

- ^Tsuji, Fisher & Reichl (2006),p. 429.

- ^abcTsuji, Fisher & Reichl (2006),pp. 241–253

- ^Kiple & Ornelas (2000),p. 1176

- ^abKobayashi, Kazuhiko; Smil, Vaclav (2012).Japan's Dietary Transition and Its Impacts.US:Massachusetts Institute of Technology.p. 18.ISBN978-0-262-01782-4.

- ^Ashkenazi, Michael; Jacob, Jeanne (2003).Food Culture in Japan.Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 37.ISBN978-0-313-32438-3.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedSeptember 24,2021.

- ^Ashcraft, Brian (May 6, 2019)."Japan's Noodle Slurping Noises Disturb Tourists, It Seems".Kotaku.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedMay 6,2019.

- ^Hosking, Richard(1995).A Dictionary of Japanese Food: Ingredients and Culture.Tuttle. p. 30.ISBN0-8048-2042-2.

- ^"Sake FAQs".Archived fromthe originalon November 6, 2014.RetrievedNovember 14,2014.

- ^"What is Shochu?".Archivedfrom the original on July 17, 2011.RetrievedDecember 31,2006.

- ^"Japanese drinking".April 13, 2007.Archivedfrom the original on March 19, 2022.RetrievedAugust 19,2017.

- ^ab"Sai さい【 thái 】ArchivedSeptember 30, 2024, at theWayback Machine",Kojien,4th ed., 1991.

- ^Shapiro, Stephanie (September 22, 2004)."Saving time, but losing a tradition among Japanese".The Baltimore Sun.Archivedfrom the original on January 15, 2020.RetrievedJanuary 15,2020.

- ^"Okazu お‐かず【 ngự sổ 】】ArchivedSeptember 30, 2024, at theWayback Machine",Kojien,4th ed., 1991.

- ^"Phúc が minh るなり vạn phúc tự hoàng bách tông đại bổn sơn vạn phúc tự ( vũ trị thị )".ひびき kỷ hành.September 3, 2011.

- ^Nagatomo, Akiko ( trường hữu ma hi tử ) (September 3, 2011)."Phổ trà liêu lý".“Kinh đô” × ( もっと ) ワかる.Industry and Tourism Bureau, City of Kyoto. Archived fromthe originalon March 4, 2016.RetrievedMay 6,2012.

- ^Andoh (2010),p. 188 – gives a recipe.

- ^Jo, Andrew."Japanese food includes dishes such as delicious Soba and Udon noodles".Archived fromthe originalon April 1, 2019.RetrievedDecember 15,2015.

- ^Davidson, Alan (2003).Seafood of South-East Asia: a comprehensive guide with recipes.Ten Speed Press. p. 34.ISBN1-58008-452-4.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedOctober 18,2015.

- ^Tsuji, Shizuo; M.F.K. Fisher (2007).Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art(25 ed.). Kodansha International. pp. 280–281.ISBN978-4-7700-3049-8.

- ^Mente, Boye Lafayette De (2007).Dining Guide to Japan: Find the Right Restaurant, Order the Right Dish, and.Tuttle Publishing. p. 70.ISBN978-4-8053-0875-2.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedOctober 16,2020.

- ^Ayao, Okumura. "Japan's Ramen Romance."Japan Quarterly48.3 (2001): 66.ProQuest Asian Business & Reference

- ^abcSeligman, Lucy. "The History of Japanese Cuisine."Japan Quarterly41.2 (1994): 165.PAO Liberal Arts Collection 1.

- ^ab『カレーライス』に quan するアンケート(in Japanese). ネットリサーチ ディムスドライブ.Archivedfrom the original on December 26, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 1,2016.

- ^Morieda Takashi. "The Unlikely Love Affair with Curry and Rice."Japan Quarterly47.2 (2000): 66.ProQuest Asian Business & Reference.

- ^Krader, Kate (September 18, 2019)."Japanese Milk Bread Is Coming for Your Lunch".Bloomberg News.Archivedfrom the original on July 2, 2021.RetrievedJuly 30,2023.

- ^Wei, Tiffany (December 20, 2021)."Yōshoku: Reformation of Eating as an Act of Nationalism".ArcGIS StoryMaps.RetrievedDecember 12,2023.

- ^"Japan's surprising 'Western' cuisine".BBC Travel.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedFebruary 4,2022.

- ^"Okonomiyaki Savoury Pancake Recipe".Japan Centre.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedMarch 27,2022.

- ^"The most delicious way to eat tonkatsu blows people's minds in Japan".SoraNews24 -Japan News-.February 20, 2024.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedAugust 31,2024.

- ^abItoh, Makiko (August 26, 2011)."Curry — it's more 'Japanese' than you think".The Japan Times.Archived fromthe originalon January 8, 2018.RetrievedMarch 31,2018.

- ^Curry RecipeArchivedJanuary 27, 2019, at theWayback MachineJapan Maritime Self-Defense Force(in Japanese)

- ^"Chicken katsu curry".Food recipes.BBC. 2016. Archived fromthe originalon July 14, 2021.RetrievedJanuary 20,2016.

- ^"They Serve What?! What Global Restaurant Chains Do Differently In Japan".Live Japan.November 29, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedApril 29,2023.

- ^Farrer, James (2015).The Globalization of Asian Cuisines: Transnational Networks and Culinary Contact Zones.Springer.ISBN9781137514080.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedFebruary 1,2018.

- ^Laemmerhirt, Iris-Aya (2014).Embracing Differences: Transnational Cultural Flows between Japan and the United States, Volume 36 of Edition Kulturwissenschaft.transcript Verlag. pp. 102–103.ISBN978-3-8394-2600-5.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedOctober 16,2020.

- ^abFitriyanti, Azi(January 25, 2014)."Japanese Cuisine in Indonesia Focuses on Taste, Menus Food Safety".Antara News.Archivedfrom the original on June 23, 2016.RetrievedMay 5,2014.

- ^"Asian Food and Australia's Changing Palate".Peril Magazine.Archived fromthe originalon April 2, 2015.RetrievedMarch 26,2015.

- ^"Top 10 Restaurants of Australia".Top 10 Restaurants.Archived fromthe originalon January 17, 2022.RetrievedMarch 26,2015.

- ^ab"Japanese Culture in Australia".Australian Good Food Guide.Archivedfrom the original on September 24, 2016.RetrievedMarch 26,2015.

- ^Kugel, Seth (November 9, 2008)."Rio de Janeiro: Koni Stores".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedMay 5,2010.

- ^De Carvalho, André; Gerhard, Felipe; Ferreira De Freitas, Ana Augusta (2020)."Food Experiences at Home: The Role of Ethnic Food in Brazilian Family Relations".Latin American Business Review.22:53–73.doi:10.1080/10978526.2020.1812399.S2CID225280313.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedSeptember 30,2020.

- ^Duke, Laura Churchill (March 4, 2021)."'Ultimate comfort food': From traditional Japanese versions to Atlantic Canadian twists, ramen popular treat ".SaltWire Network. SaltWire.RetrievedApril 5,2022.

- ^"Chicken Teriyaki bento set".Ichiban Sushi.Archived fromthe originalon March 19, 2022.RetrievedJuly 26,2017.

- ^"7 Best Japanese Resto in Jakarta's Little Tokyo (Melawai)".Wanderbites.July 29, 2016. Archived fromthe originalon March 30, 2022.RetrievedJuly 26,2017.

- ^Japanese Food Favorit ala Cafe(in Indonesian). Gramedia Pustaka Utama.ISBN9789792227284.

- ^Media, Kompas Cyber (February 10, 2011)."Okonomiyaki Merambah Kaki Lima".Kompas.com(in Indonesian).Archivedfrom the original on September 15, 2018.RetrievedSeptember 15,2018.

- ^"10 Japanese Street Food yang Bisa Kamu Temukan di Jakarta".Qraved Journal.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedSeptember 19,2018.

- ^Mustinda, Lusiana."Yang Hangat! di 4 Tempat Ini Ada Oden Enak dengan Harga Terjangkau".detikfood(in Indonesian).Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedSeptember 19,2018.

- ^"New: Suntiang, When Padang Marries Japanese Food".Culinary Bonanza. February 6, 2014. Archived fromthe originalon May 5, 2014.RetrievedMay 5,2014.

- ^Resty Woro Yuniar (February 21, 2014)."Food Fridays: When Rendang Said 'I Do' to Sushi".The Wall Street Journal.Archived fromthe originalon September 8, 2018.RetrievedAugust 4,2017.

- ^I. Christianto (November 30, 2009)."Enjoying internationally popular Japanese food".The Jakarta Post.Archivedfrom the original on March 19, 2022.RetrievedMay 5,2014.

- ^"Yoshinoya Indonesia".Archived fromthe originalon May 1, 2018.RetrievedDecember 17,2018.

- ^Cheryl M. Arcibal (July 8, 2013)."Latest Japanese resto in town wants to conquer Pinoy bellies with pork and ramen | Food".The Philippine Star.Archivedfrom the original on March 19, 2022.RetrievedMarch 3,2014.

- ^[1]ArchivedJuly 1, 2012, at theWayback Machine

- ^Adachi, Nobuko (2006).Japanese Diasporas: Unsung Pasts, Conflicting Presents and Uncertain Futures.Taylor & Francis.ISBN9780203968840.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedMarch 3,2014– via Google Books.

- ^"From sushi to tempura to Wagyu: Japanese food 101".May 15, 2012.Archivedfrom the original on February 27, 2014.RetrievedJanuary 8,2014.

- ^Tiu, Cheryl (December 31, 2012)."Best of Manila | CNN Travel".CNN.Archived fromthe originalon February 22, 2014.RetrievedMarch 3,2014.

- ^Ocampo, Ambeth R. (August 30, 2012)."Japanese origins of the Philippine 'halo-halo'".Philippine Daily Inquirer.Archivedfrom the original on April 23, 2019.RetrievedApril 23,2019.

- ^"Halo-Halo Graham Float Recipe".Pinoy Recipe at Iba Pa.July 24, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on July 24, 2019.RetrievedJuly 24,2019.

- ^Crisol, Christine (2006). "AHalo-HaloMenu ". In Zialcita, Fernando N. (ed.).Quiapo: Heart of Manila.Manila: Quiapo Printing. p. 321.ISBN978-971-93673-0-7.

Today, many non-Quiapense informants in their forties and older associate the Quinta Market with this dessert. Why did this market become important in the invention of this dessert? Aside from its being a Japanese legacy in the area [...] of all the city markets, the Quinta was closest to the ice.

- ^Sparks, Ph (October 28, 2021)."Sachiko's Little Kyoto makes you feel like you're in Japan".Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedJuly 20,2022.

- ^"Sachiko's Little Kyoto: A Little Slice of Japan in Cebu".November 7, 2021.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedDecember 30,2021.

- ^Polistico, Edgie (2017).Philippine Food, Cooking, & Dining Dictionary.Anvil Publishing, Inc.ISBN9786214200870.

- ^Polistico, Edgie."Odong".Philippine Food Illustrated.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedJanuary 18,2022.

- ^abRamos, Ige (November 18, 2013)."Kumain at tumulong".Bandera.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedJanuary 18,2022.

- ^"Odong, Sardinas at Patola a la MaiMai".Market Manila.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedJanuary 18,2022.

- ^abcd"Odong Recipe".Panlasang Pinoy.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedJanuary 18,2022.

- ^Ong, Kenneth Irvin (October 18, 2018)."For the love of Ligo Sardines".Edge Davao.Archivedfrom the original on October 22, 2018.RetrievedJanuary 18,2022.

- ^ab"Sardines with Odong Noodles".Kusina ni Teds.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedJanuary 18,2022.

- ^abFigueroa, Antonio V. (September 12, 2016)."US, Japan linguistic legacies".Edge Davao.No. 142. p. 9.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedJanuary 18,2022.

- ^Goodman, Grant K. (1967). "Japanese Percentage of Participation in Davao Province Industries".Davao: A Case Study in Japanese-Philippine Relations.University of Kansas,Center for East Asian Studies. p. 26.hdl:1808/1195.Archivedfrom the original on August 7, 2022.

- ^Katakura, Yoshifumi[in Japanese](2016)."Phiến thương giai sử の đài loan lịch sử kỷ hành đệ nhất hồi cảng loan đô thị ・ cơ long を phóng ねる"(PDF).Japan–Taiwan Exchange Association.p. 9.Archived(PDF)from the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedMarch 23,2020.

- ^Ishige, Naomichi[in Japanese](2014).The History and Culture of Japanese Food.Routledge. p. 246.ISBN978-1136602559.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedOctober 16,2020.

- ^"“さつま dương げ” の các đô đạo phủ huyện での hô び danh を điều tra quan tây は “Thiên ぷら” ".J-TOWN.NET. June 16, 2017.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedMarch 23,2020.

- ^"Burgeoning growth of Japanese cuisine in Thailand".The Nation.September 24, 2012. Archived fromthe originalon February 4, 2018.RetrievedApril 12,2016.

- ^abRenton, Alex (February 26, 2006)."How Sushi ate the World".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on January 13, 2008.RetrievedAugust 20,2006.

- ^abJi-Song Ku, Robert (2013).Dubious Gastronomy: The Cultural Politics of Eating Asian in the USA.University of Hawaii Press.pp. 43–48.ISBN978-0-824-83920-8.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedJanuary 28,2020.

- ^Passy, Charles (August 26, 2015)."Meet the Pilot Who Doubles as Block Island's Chinese-Food Delivery Guy".The Wall Street Journal.pp. A1.Archivedfrom the original on March 19, 2022.RetrievedAugust 26,2015.

- ^Ji-Song Ku (2013),p. 263.

- ^Claiborne, Craig (November 11, 1963)."Restaurants on Review; Variety of Japanese Dishes Offered, But Raw Fish Is Specialty on Menu".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on December 2, 2022.RetrievedAugust 3,2018.

- ^"The chef, obsessed: Nobuyoshi Kuraoka established his own local buckwheat farm to achieve the perfect soba noodle".Politico PRO.RetrievedAugust 3,2018.

- ^Fabricant, Florence (October 6, 1982)."Adapting American Foods to Japanese Cuisine".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on December 2, 2022.RetrievedAugust 3,2018.

- ^Johnson, Eric (August 30, 2001),"American-style peace redefines Japanese palate",Japan Times,archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024,retrievedMarch 24,2019

- ^"The Kitchenless Restaurant",Kitchen Planning,vol. 6, p. 63, December 1968,archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024,retrievedJanuary 28,2020

- ^"Why Hibachi Is Complicated"(Audio Podcast with Notes).Sporkful.March 11, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedMarch 24,2019.

- ^"Ikizukuri: As Fresh As Seafood Can Get".US represented.August 19, 2018. Archived fromthe originalon December 3, 2019.RetrievedSeptember 12,2020.

- ^"Faostat".Archivedfrom the original on May 11, 2017.RetrievedSeptember 30,2020.

- ^McCurry, Justin (November 10, 2016)."Trouble at Tsukiji: world's biggest fish market caught in controversy".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on June 13, 2022.RetrievedDecember 1,2016.

- ^"Whale meat trade continues in East Asia".WWF.Archived fromthe originalon December 2, 2016.RetrievedDecember 7,2016.

- ^"Whaling in Japan".Whale and Dolphin Conservation.Archivedfrom the original on January 9, 2019.RetrievedDecember 2,2016.

Works cited

[edit]- Andoh, Elizabeth (2010),Kansha: Celebrating Japan's Vegan and Vegetarian Traditions,Random HouseDigital,ISBN978-1-58008-955-5

- Andoh, Elizabeth (2012),Washoku: Recipes from the Japanese Home Kitchen,Random House Digital,ISBN978-0-307-81355-8

- Cawthorn, M. W. (1997)."Meat consumption from stranded whales and marine mammals in New Zealand: Public health and other issues"(PDF).Conservation Advisory Science Notes(164). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation.ISSN1171-9834.Archived(PDF)from the original on December 6, 2013.

- Hepburn, James Curtis(1888).A Japanese-English and English-Japanese Dictionary(4 ed.). Tokyo: Z.P. Maruya & Company.Archivedfrom the original on September 30, 2024.RetrievedOctober 18,2015.

- Kiple, Kenneth F.; Ornelas, Kriemhild (2000).The Cambridge World History of Food.Vol. 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-40216-6.Archived fromthe originalon May 4, 2012.

- Shimbo, Hiroko (2000),The Japanese Kitchen: 250 Recipes in a Traditional Spirit,Harvard Common Press,ISBN978-1-55832-177-9

- Tsuji, Shizuo; Fisher, M.F.K.; Reichl, Ruth (2006),Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art,Kodansha International,ISBN978-4-7700-3049-8

Further reading

[edit]- Cwiertka, Katarzyna Joanna (2006),Modern Japanese Cuisine: Food, Power And National Identity,Reaktion Books,ISBN978-1-86189-298-0

- Francks, Penelope. "Diet and the comparison of living standards across the Great Divergence: Japanese food history in an English mirror."Journal of Global History14.1 (2019): 3-21.

- Rath, Eric C. (2010),Food and Fantasy in Early Modern Japan,University of California Press,ISBN978-0-520-26227-0

External links

[edit]- JAPANESE CUISINE COMPLETEJapanese Culinary Academy, Kyoto Prefectual University