1900 Amur anti-Chinese pogroms

You can helpexpand this article with text translated fromthe corresponding articlein Chinese.(May 2019)Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This articleis missing informationabout specific background, aftermath and reviews.(May 2019) |

| 1900 Amur anti-Chinese pogroms GengziRussian disaster | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of theRussian invasion of Manchuria | |||||||||

In the Blagoveshchensk massacre, a Qing civilian was tied for execution. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 36,000 Russian soldiers andCossacks | 22,000 civilians | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| none[citation needed] |

198 officials died[1] 7,000 Chinese citizens died | ||||||||

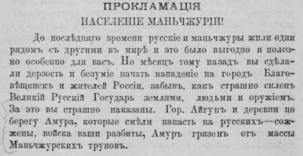

The1900 Amur anti-Chinese pogroms(Chinese:Canh tử nga nan) were a series ofethnic killings(pogroms) and reprisals undertaken by theRussian Empireagainst subjects of theQing dynastyof various ethnicities, includingManchu,Daur,andHanpeoples. They took place inBlagoveshchenskand in theSixty-Four Villages East of the Riverin theAmur region,during the same time as theBoxer Rebellionin China. The events ultimately resulted in thousands of deaths, the loss of residency for Chinese subjects living in the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River, and increased Russian control over the region. The Russian justification for the pogroms were attacks made on Russian infrastructure outside Blagoveshchensk byChinese Boxers,which was then responded by Russian force. The pogroms themselves occurred in 17–21 July [O.S.4–8 July] 1900.

Name[edit]

The name for the killings and reprisals that occurred in Amur is not standardized, and has been referred to by different names over time. The most common Chinese name for the pogroms is theGengziRussian disaster(traditional Chinese:Canh tử nga nan;simplified Chinese:Canh tử nga nan;pinyin:Gēngzǐ é nán), but the two most major events in Blagoveshchensk and the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River are referred to as theBlagoveshchensk massacre(traditional Chinese:Hải lan phao thảm án;simplified Chinese:Hải lan phao thảm án;pinyin:Hǎilánpào cǎn'àn) and theSixty-Four Villages East of the River massacre(traditional Chinese:Giang đông lục thập tứ truân thảm án;simplified Chinese:Giang đông lục thập tứ truân thảm án;pinyin:Jiāngdōng liùshísì tún cǎn'àn) respectively.[2]

The Russian name of the pogroms in Blagoveshchensk is referred to as theChinese pogrom in Blagoveshchensk(Russian:китайский погром в Благовещенске), while the killings and reprisals that took place in the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River are referred to as theBattle on the Amur(Russian:бои на Амуре).[3]

Background[edit]

This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(May 2019) |

Blagoveshchenskwas founded on the territory ceded to Russia by theTreaty of Aigunin 1858.

Process[edit]

Blagoveshchensk[edit]

This section is empty.You can help byadding to it.(May 2019) |

Sixty-Four Villages East of the River[edit]

Lieutenant-General Konstantin Gribskiy ordered the expulsion of all Qing subjects who remained north of the river.[4]This included the residents of the villages, and Chinese traders and workers who lived in Blagoveshchensk proper, where they numbered anywhere between one-sixth and one-half of the local population of 30,000.[4][5]They were taken by the local police and driven into the river to be drowned. Those who could swim were shot by the Russian forces.[6]There were 1,266 households, including 900 Daurs and 4,500 Manchus in the area until the massacre.[7]Many Manchu villages were burned byCossacksin the massacre according to Victor Zatsepine.[8]

Legacy[edit]

Andrew Higgins ofThe New York Timeswrote that Chinese and Russian officials tended to not bring up the incidents during periods of goodChina–Russia relationsorSino-Soviet relations,while the incident was brought up after theSino-Soviet splitwith people still alive who had been in the pogroms being interviewed by Chinese officials. Higgins stated that in 2020 Chinese and Russian officials purposefully avoided dealing with the incident.[8]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Sun, Rongtu; Xu, Xilian (1974).Ái hồn huyện chí[Annals of Aihui County] (in Chinese). Taipei: Cheng Wen Publishing Co., Ltd. pp. 209–210.

- ^Gao, Yongsheng; Li, Lingbao (March 2004)."Canh tử nga nan" thời hạn đích tái giới định dữ tư khảo[Redefinition and Reflection on the Dates of the "GengziRussian Disaster "].History of Heilongjiang(in Chinese): 35–36.doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-020X.2004.03.015.ISSN1004-020X.

- ^Piskunov, Sergey (12 December 2001). Rumyantsev, Vyacheslav (ed.)."Боксерское" восстание в Китае в 1898 - 1901[ "Boxer" Uprising in China in 1898–1901].hrono.ru(in Russian).Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2003.Retrieved21 December2019.

- ^abPaine, S. C. M.(1996).Imperial Rivals: China, Russia, and Their Disputed Frontier.Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe.ISBN978-1-56324-724-8.Retrieved8 May2019.[pages needed]

- ^Yan, Jiaqi(28 February 2005).Trung nga biên giới vấn đề đích thập cá sự thật ── hồi ứng nga la tư trú trung quốc đại sử quán công sử hàm tham tán cương sát lạc phu đẳng nhân văn chương[Ten facts about the Sino-Russian border problem: In reply to the essays by Russian Minister-Counselor to China Sergey Goncharov and other people].Twenty-First Century(in Chinese) (35) (Online ed.). Archived fromthe originalon 14 April 2005.Retrieved24 February2009.

- ^Maxwell, Neville(2007)."How the Sino-Russian Boundary Conflict Was Finally Settled: From Nerchinsk 1689 to Vladivostok 2005 via Zhenbao Island 1969"(PDF).In Iwashita, Akihiro (ed.).Eager Eyes Fixed on Eurasia.Vol. 2: Russia and Its Eastern Edge. Sapporo: Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University. pp. 47–72.Retrieved24 February2009.

- ^Military Scientific Committee of the General Staff (1886).Сборникъ географическихъ, топографическихъ и статистическихъ матеріаловъ по Азіи[Collection of Geographic, Topographic and Statistical Materials on Asia] (in Russian). Vol. XXXI. Saint Petersburg: Military Printing House (in theGeneral Staff Building). p. 185.

- ^abHiggins, Andrew (26 March 2020)."On Russia-China Border, Selective Memory of Massacre Works for Both Sides".The New York Times.Retrieved31 March2020.

Further reading[edit]

- Yang, Chuang; Gao, Fei; Feng (2006).Hải lan phao hòa giang đông lục thập tứ truân thảm án[The Tragic Case of Blagoveshchensk/Hailanpao and the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River].Bách niên trung nga quan hệ[A Century of China–Russia Relations] (in Chinese). Beijing: World Affairs Press.ISBN7-5012-2876-0.