A Legend of Old Egypt

"A Legend of Old Egypt"(Polish:"Z legend dawnego Egiptu") is a seven-pageshort storybyBolesław Prus,originally published January 1, 1888, inNew Year's supplements to theWarsawKurier Codzienny(Daily Courier) andTygodnik Ilustrowany(Illustrated Weekly).[1]It was his first piece ofhistorical fictionand later served as a preliminary sketch for his onlyhistorical novel,Pharaoh(1895), which would be serialized in the Illustrated Weekly.[2]

"A Legend of Old Egypt" andPharaohshow unmistakable kinships insetting,themeanddenouement.[3]

Plot

[edit]| "A Legend of Old Egypt" | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Short storybyBolesław Prus | |||

| Original title | 'Z legend dawnego Egiptu' | ||

| Translator | Christopher Kasparek | ||

| Country | Poland | ||

| Language | Polish | ||

| Genre(s) | Historicalshort story | ||

| Publication | |||

| Published in | Kurier Codzienny,andTygodnik Ilustrowany(Warsaw) | ||

| Media type | |||

| Publication date | 1 January 1888 | ||

| Chronology | |||

| |||

ThecentenarianpharaohRamses is breathing his last, "his chest... invested by a stifling incubus [that drains] the blood from his heart, the strength from his arm, and at times even the consciousness from his brain." He commands the wisest physician at theTemple of Karnakto prepare him a medicine that kills or cures at once. After Ramses drinks thepotion,he summons anastrologerand asks what the stars show. The astrologer replies that heavenly alignments portend the death of a member of thedynasty;Ramses should not have taken the medicine today. Ramses then asks the physician how soon he will die; the physician replies that before sunrise either Ramses will be hale as a rhino, or his sacred ring will be on the hand of his grandson and successor, Horus.

Ramses commands that Horus be taken to the hall of the pharaohs, there to await his last words and the royal ring. Amid the moonlight, Horus seats himself on the porch, whose steps lead down to theRiver Nile,and watches the crowds gathering to greet their soon-to-be new pharaoh. As Horus contemplates the reforms that he would like to introduce, something stings his leg; he thinks it was abee.Acourtierremarks that it is fortunate that it was not aspider,whosevenomcan be deadly at this time of year.

Horus orders edicts drawn up, ordaining peace withEgypt's enemies, theEthiopians,and forbidding that prisoners of war have their tongues torn out on the field of battle; lowering the people's rents and taxes; giving slaves days of rest and forbidding their caning without a court judgment; recalling Horus' teacher Jethro, whom Ramses had banished for instilling in Horus an aversion to war and compassion for the people; moving, to the royal tombs, the body of Horus' mother Sephora which, because of the mercy that she had shown the slaves, Ramses had buried among the slaves; and releasing Horus' beloved, Berenice, from the cloister where Ramses had imprisoned her.

Meanwhile, Horus' leg has become more painful. The physician examines it and finds that Horus has been stung by a very poisonous spider. He has only a short time to live.

The ministers enter with the edicts that they have drawn up at his bidding, and Horus awaits the death of Ramses so that he may touch and thus confirm his edicts with the sacred ring of the pharaohs.

As death approaches Horus, and it becomes increasingly unlikely that he will have time to touch every edict with the ring, he lets successive edicts slip to the floor: the edict on the people's rents and the slaves' labor; the edict on peace with the Ethiopians; the edict moving his mother Sephora's remains; the edict recalling Jethro from banishment; the edict on not tearing out the tongues of prisoners taken in war. There remains only the edict freeing his love, Berenice.

Just then, thehigh priest's deputy runs into the hall and announces a miracle. Ramses has recovered and invites Horus to join him in alionhunt at sunrise.

Horus looked with failing eye across the Nile, where the light shone in Berenice's prison, and two [...] sanguineous tears rolled down his face.

"You do not answer, Horus?" asked Ramses' messenger, in surprise.

"Don't you see he's dead?..." whispered the wisest physician in Karnak.

Behold, human hopes are vain before the decrees that the Eternal writes in fiery signs upon the heavens.

Inspiration

[edit]The inspiration for theshort storywas investigated in a 1962 paper by the foremostPrusscholar,Zygmunt Szweykowski.[4]

What prompted Prus, erstwhile foe ofhistorical fiction,to take time in December 1887, in the midst of writing ongoing newspaper instalments of his second novel,The Doll(1887–89), to pen his first historical story? What could have moved him so powerfully?

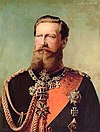

Szweykowski follows several earlier commentators in concluding that it was contemporary German dynastic events. In late October 1887, Germany's first modern emperor, the warlikeKaiser Wilhelm I,had taken cold during a hunt and soon appeared to be at death's door; by November 2 a rumor spread that he had died. He rallied, however. Meanwhile, his son and successor, thereform-mindedCrown Prince Friedrich(in English, "Frederick" ), an inveterate smoker, had for several months been undergoing treatment for a throat ailment; the foreign press had written of a dire situation, but only on November 12 did the official German press announce that he in fact hadthroatcancer.

Prince Frederick had been an object of lively interest among progressive Europeans, who hoped that his eventual reign would bring a broad-basedparliamentary system,democratic freedoms,peace, andequal rightsfor non-German nationalities, including Poles, within theGerman Empire.

Szweykowski points out that the "Legend's" contrast between the despotic centenarian Pharaoh Ramses and his humane grandson and successor Horus was, in its historic Germanprototypes,doubled, with Prince Frederick actually facingtwoantagonists: his father, Kaiser Wilhelm I, and the "Iron Chancellor",Otto von Bismarck.In a curious further parallel, a month after Kaiser Wilhelm's illness, Bismarck suffered astroke.

Bolesław Prus,who in his "Weekly Chronicles" frequently touched on political events in Germany, devoted much of his December 4, 1887, column to Prince Frederick and his illness. The latest news from Germany and fromSan Remo,Italy, where the Prince was undergoing treatment, had been encouraging. Prus wrote with relief that "the Successor to the German Throne reportedly does not have cancer." By mid-December, however, the politically inspired optimism in the Berlin press had again yielded to a sense of despair.

"It was then [states Szweykowski] that Prus wrote 'A Legend of Old Egypt,' shifting a contemporary subject into the past. Prus must have found this maneuver necessary in order to bring to completion what had not yet been completed, avoidsensationalism,and gainperspectivesthat generalized a particular fact to all human life; the atmosphere oflegendwas particularly favorable to this.

"In putting Horus to death while Prince Frederick still lived, Prus anticipated events, but he erred only in details, not in the essence of the matter, which was meant to document the idea that 'human hopes are vain before the order of the world.' Frederick, to be sure, did mount the throne (asFrederick III) in March the following year (Kaiser Wilhelm I died on March 9, 1888) and for a brief time it seemed that a new era would begin for Germany, and indirectly for Europe. "[5]

But it was not to be. Frederick III survived his father by only 99 days, dying atPotsdamon June 15, 1888, and leaving the German throne to his bellicose sonWilhelm II,who a quarter-century later would help launch World War I.

The connection between the German dynastic events and the genesis of Prus' "Legend of Old Egypt" was recognized in the Polish press already in 1888, even before Frederick's accession to short-lived impotent power, by a pseudonymous writer who styled himself "Logarithmus."[6]

As Szweykowski observes, "the direct connection between the short story and political events in contemporaneous Germany doubtless opens new suggestions for the genesis ofPharaoh."[7]

Influences

[edit]

In addition to the German elements, there were other influences on the composition of the short story. These included:

- the use of a device inspired by the ancientGreek chorus,in this case stating at the opening and at the end, and repeating once in the course of the text, a sentiment about the vanity of human hopes before the decrees of heaven;

- astrologicalechoes from Prus' own newspaper account of thesolar eclipsethat he had witnessed atMława,north ofWarsaw,four months earlier, on August 19, 1887;[8]

- the history ofPharaohRamses II( "the Great" ), who had lived nearly as long as the "Legend's" "hundred-year-old Ramses" (who is also referred to in Prus' story as "great Ramses" ) and had outliveddozensof his own potentialsuccessors;

- and theRomanpoetHorace's sentiment,"Non omnis moriar"( "I shall not die altogether" ), which Prus cites in Polish in the "Legend" and will cite in the originalLatinat the end ofThe Doll,which he is also writing just then.

Characters

[edit]For Prus it wasaxiomaticthathistorical fictionmust distort history. Characteristically, at times, in historical fiction, his choices of characters' names show considerable arbitrariness: nowhere more so than in "A Legend of Old Egypt."[9]

- The protagonist is assigned the name of the hawk-headedEgyptiangodHorus;

- Horus' mother, theGreekvariant of the name of theBiblicalMoses' wife,Sephora(Exodus 2:21);

- Horus' teacher, the name ofMoses' father-in-law,Jethro(Exodus 3:1); and

- Horus' beloved, aGreekname that means "bearer of victory",Berenice(there were several Egyptian queens of that name in thePtolemaic period).

Pharaoh

[edit]"A Legend of Old Egypt," published in 1888, shows unmistakable kinships insetting,themeanddenouementwithPrus' 1895 novelPharaoh,for which the short story served as a preliminary sketch.[10]

Both works of fiction are set inancient Egypt— the "Legend," at some indeterminate time, presumably during the19thor20th Dynasty,when all theRamessidepharaohs reigned;Pharaoh,at the fall of the20th DynastyandNew Kingdomin the 11th century BCE.

In each, the protagonist (Horus, and Ramses XIII,[11]respectively) aspires to introducesocial reforms.(Ramses also planspreventive waragainst a risingAssyrianpower.)

In each, the protagonist perishes before he can implement his plans — though, in the novel, some of these are eventually realized by Ramses' adversary and successor,Herihor.[12]

See also

[edit]- "The Barrel Organ"

- "Fading Voices"

- "The Living Telegraph"(amicro-storybyBolesław Prus).

- Micro-story

- "Mold of the Earth"(amicro-storybyBolesław Prus).

- Pharaoh(historical novelbyBolesław Prus).

- Prose poetry

- "Shades"(amicro-storybyBolesław Prus).

- "The Waistcoat"

Notes

[edit]- ^Krystyna Tokarzówna and Stanisław Fita,Bolesław Prus, 1847-1912,p. 376.

- ^Christopher Kasparek,"Prus'Pharaoh:the Creation of a Historical Novel ",The Polish Review,1994, no. 1, p. 46.

- ^Christopher Kasparek,"Prus'Pharaoh:the Creation of a Historical Novel ", p. 46.

- ^Zygmunt Szweykowski,"Geneza noweli 'Z legend dawnego Egiptu'".

- ^Zygmunt Szweykowski,p. 259.

- ^Zygmunt Szweykowski,p. 300.

- ^Zygmunt Szweykowski,p. 261.

- ^Christopher Kasparek,"Prus'Pharaohand the Solar Eclipse ",The Polish Review,1997, no. 4, p. 473, note 7, and p. 477.

- ^Christopher Kasparek,"Prus'Pharaoh:the Creation of a Historical Novel ", p. 48.

- ^Christopher Kasparek,"Prus'Pharaoh:the Creation of a Historical Novel ", p. 46.

- ^Actually, Egypt's lastRamessidepharaoh wasRamses XI,not "Ramses XIII."

- ^Bolesław Prus,Pharaoh,translated from thePolishbyChristopher Kasparek(2nd, revised ed., 2001), p. 618.

References

[edit]- Zygmunt Szweykowski,"Geneza noweli 'Z legend dawnego Egiptu'"( "The Genesis of the Short Story, 'A Legend of Old Egypt,'" originally published 1962), reprinted in his book,Nie tylko o Prusie: szkice(Not Only about Prus: Sketches), Poznań, Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 1967, pp. 256–61, 299-300.

- Krystyna Tokarzówna and Stanisław Fita,Bolesław Prus, 1847-1912: kalendarz życia i twórczości, pod redakcją Zygmunta Szweykowskiego(Bolesław Prus,1847-1912: a Calendar of [His] Life and Work, edited byZygmunt Szweykowski), Warsaw, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1969.

- Christopher Kasparek,"Prus'Pharaoh:the Creation of a Historical Novel ",The Polish Review,1994, no. 1, pp. 45–50.

- Christopher Kasparek,"Prus'Pharaohand the Solar Eclipse ",The Polish Review,1997, no. 4, pp. 471–78.

- Bolesław Prus,Pharaoh,translated from thePolishbyChristopher Kasparek(2nd, revised ed.), Warsaw, Polestar Publications (ISBN83-88177-01-X), and New York,Hippocrene Books,2001.

- Jakub A. Malik,Ogniste znaki Przedwiecznego. Szyfry transcendencji w noweli Bolesława Prusa "Z legend dawnego Egiptu". Próba odkodowania( "Fiery Signs of the Eternal: Ciphers of Transcendence in Bolesław Prus' Short Story 'A Legend of Old Egypt': An Attempt at Decoding" ), in Jakub A. Malik, ed.,Poszukiwanie świadectw. Szkice o problematyce religijnej w literaturze II połowy XIX i początku XX wieku(Search for Testimonies: Sketches on Religious Themes in Literature of the Second Half of the 19th and the Early 20th Centuries),Lublin,Wydawnictwo TNKUL,2009.