Abolitionism

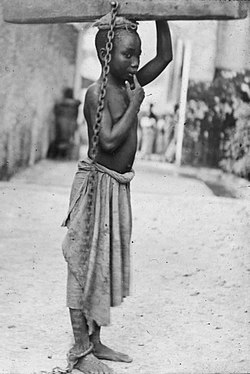

| Part ofa serieson |

| Forced labourandslavery |

|---|

|

Abolitionism,or theabolitionist movement,is the movement to endslaveryand liberate slaves around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery wasFrancein 1315, but it was later used in itscolonies.Under the actions ofToyotomi Hideyoshi,chattel slavery has been abolished acrossJapansince 1590, though other forms offorced labourwere used duringWorld War II.The first and only country to self-liberate from slavery was actually a former French colony,Haiti,as a result of theRevolution of 1791–1804.TheBritish abolitionistmovement began in the late 18th century, and the 1772Somersett caseestablished that slavery did not exist in English law. In 1807, the slave trade was made illegal throughout the British Empire, though existing slaves in British colonies were not liberated until theSlavery Abolition Act in 1833.Vermontwas the first state in America to abolish slavery in 1777. By 1804, the rest ofthe northern states had abolished slaverybut it remained legal in southern states. By 1808, the United States outlawed theimportation of slavesbut did not ban slavery outright until 1865.

In Eastern Europe, groups organized to abolish the enslavement of theRomainWallachiaandMoldaviabetween 1843 and 1855, andto emancipate the serfs in Russia in 1861.TheUnited Stateswould pass the13th Amendmentin December 1865 after having just fought a bloodyCivil War,ending slavery "except as a punishment for crime". In 1888,Brazilbecame the last country in the Americas tooutlaw slavery.As theEmpire of Japanannexed Asian countries, from the late 19th century onwards, archaic institutions including slavery were abolished in those countries.

After centuries of struggle, slavery was eventually declared illegal at the global level in 1948 under theUnited Nations'Universal Declaration of Human Rights.Mauritaniawas the last country to officially abolish slavery, with a presidential decree in 1981.[1]Today, child and adult slaveryandforced labourare illegal in almost all countries, as well as being againstinternational law,buthuman traffickingfor labour and forsexual bondagecontinues to affect tens of millions of adults and children.

France[edit]

Early abolition in metropolitan France[edit]

Balthild of Chelles,herself a former slave,queen consortof Neustria and Burgundy by marriage toClovis II,became regent in 657 since the king, her sonChlothar III,was only five years old. At some unknown date during her rule, she abolished the trade of slaves, although not slavery. Moreover, her (and contemporaneousSaint Eligius') favorite charity was to buy and free slaves, especially children. Slavery started to dwindle and would be superseded byserfdom.[2][3]

In 1315,Louis X,king of France, published a decree proclaiming that "France signifies freedom" and that any slave setting foot on French soil should be freed. This prompted subsequent governments to circumscribe slavery in theoverseas colonies.[4]

Some cases of African slaves freed by setting foot on French soil were recorded such as the example of aNormanslave merchant who tried to sell slaves inBordeauxin 1571. He was arrested and his slaves were freed according to a declaration of theParlementofGuyennewhich stated that slavery was intolerable in France, although it is a misconception that there were 'no slaves in France'; thousands of African slaves were present in France during the 18th century.[5][6]Born into slavery inSaint Domingue,Thomas-Alexandre Dumasbecame free when his father brought him to France in 1776.

Code Noirand Age of Enlightenment[edit]

As in otherNew Worldcolonies, the French relied on theAtlantic slave tradefor labour for theirsugar caneplantationsin their Caribbean colonies; theFrench West Indies.In addition, French colonists inLouisianein North America held slaves, particularly in the South aroundNew Orleans,where they established sugarcane plantations.

Louis XIV'sCode Noirregulated the slave trade and institution in the colonies. It gave unparalleled rights to slaves. It included the right to marry, gather publicly or take Sundays off. Although theCode Noirauthorized and codified cruel corporal punishment against slaves under certain conditions, it forbade slave owners to torture them or to separate families. It also demanded enslaved Africans receive instruction in the Catholic faith, implying that Africans were human beings endowed with a soul, a fact French law did not admit until then. It resulted in a far higher percentage of Black people being free in 1830 (13.2% inLouisianacompared to 0.8% inMississippi).[7]They were on average exceptionally literate, with a significant number of them owning businesses, properties, and even slaves.[8][9]Other free people of colour, such asJulien Raimond,spoke out against slavery.

TheCode Noiralso forbade interracial marriages, but it was often ignored in French colonial society and themulattoesbecame an intermediate caste between whites and blacks, while in the British colonies mulattoes and blacks were considered equal and discriminated against equally.[9][10]

During theAge of Enlightenment,many philosophers wrote pamphlets against slavery and its moral and economical justifications, includingMontesquieuinThe Spirit of the Laws(1748) andDenis Diderotin theEncyclopédie.[11]In 1788,Jacques Pierre Brissotfounded theSociety of the Friends of the Blacks(Société des Amis des Noirs) to work for the abolition of slavery. After the Revolution, on 4 April 1792, France grantedfree people of colourfull citizenship.

The slave revolt, in the largest Caribbean French colony ofSaint-Dominguein 1791, was the beginning of what became theHaitian Revolutionled by formerly enslaved people likeGeorges Biassou,Toussaint L'Ouverture,andJean-Jacques Dessalines.The rebellion swept through the north of the colony, and with it came freedom to thousands of enslaved blacks, but also violence and death.[12]In 1793, French Civil Commissioners in St. Domingue and abolitionists,Léger-Félicité SonthonaxandÉtienne Polverel,issued the first emancipation proclamation of the modern world (Decree of 16 Pluviôse An II). The Convention sent them to safeguard the allegiance of the population to revolutionary France. The proclamation resulted in crucial military strategy as it gradually brought most of the black troops into the French fold and kept the colony under the French flag for most of the conflict.[13]The connection with France lasted until blacks and free people of colour formed L'armée indigène in 1802 to resistNapoleon'sExpédition de Saint-Domingue.Victory over the French in the decisiveBattle of Vertièresfinally led to independence and the creation of presentHaitiin 1804.[14]

First general abolition of slavery (1794)[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2019) |

The convention, the first elected Assembly of theFirst Republic(1792–1804), on 4 February 1794, under the leadership ofMaximilien Robespierre,abolished slavery in lawin France and its colonies.[15]Abbé Grégoireand the Society of the Friends of the Blacks were part of the abolitionist movement, which had laid important groundwork in building anti-slavery sentiment in themetropole.The first article of the law stated that "Slavery was abolished" in the French colonies, while the second article stated that "slave-owners would be indemnified" with financial compensation for the value of their slaves. The French constitution passed in 1795 included in the declaration of the Rights of Man that slavery was abolished.

Re-establishment of slavery in the colonies (1802)[edit]

During theFrench Revolutionary Wars,French slave-owners joined thecounter-revolutionen masse and, through theWhitehall Accord,they threatened to move the French Caribbean colonies under British control, as Great Britain still allowed slavery. Fearing secession from these islands, successfully lobbied by planters and concerned about revenues from the West Indies, and influenced by the slaveholder family ofhis wife,Napoleon Bonapartedecided to re-establish slavery after becomingFirst Consul.He promulgated thelaw of 20 May 1802and sent military governors and troops to the colonies to impose it.

On 10 May 1802,Colonel Delgrèslaunched a rebellion inGuadeloupeagainst Napoleon's representative,General Richepanse.The rebellion was repressed, and slavery was re-established.

Abolition of slavery in Haiti (1804)[edit]

The news of theLaw of 4 February 1794that abolished slavery in France and its colonies and the revolution led byColonel Delgrèssparked another wave of rebellion in Saint-Domingue. From 1802 Napoleon sent more than 20,000 troops to the island, two-thirds died, mostly from yellow fever.

Seeing the failure of theSaint-Domingue expedition,in 1803 Napoleon decided toselltheLouisiana Territoryto the United States.

The French governments initially refused to recognize Haïti. It forced the nation to pay a substantial amount of reparations (which it could ill afford) for losses during the revolution and did not recognize its government until 1825.

France was a signatory to the firstmultilateral treatyfor the suppression of the slave trade, theTreaty for the Suppression of the African Slave Trade(1841), but the king,Louis Philippe I,declined to ratify it.

Second abolition (1848) and subsequent events[edit]

On 27 April 1848, under theSecond Republic(1848–1852), thedecree-lawwritten byVictor Schœlcherabolished slavery in the remaining colonies. The state bought the slaves from thecolons(white colonists;BékésinCreole), and then freed them.

At about the same time, France started colonizing Africa and gained possession of much of West Africa by 1900. In 1905, the French abolished slavery in most ofFrench West Africa.The French also attempted to abolish Tuareg slavery following theKaocen Revolt.In the region of the Sahel, slavery has long persisted.

Passed on 10 May 2001, theTaubiralaw officially acknowledges slavery and the Atlantic slave trade as acrime against humanity.10 May was chosen as the day dedicated to recognition of the crime of slavery.

Great Britain[edit]

Overview[edit]

James Oglethorpewas among the first to articulate theEnlightenmentcase against slavery, banning it in theProvince of Georgiaon humanitarian grounds, and arguing against it in Parliament. Soon after Oglethorpe's death in 1785, Sharp and More united withWilliam Wilberforceand others in forming theClapham Sect.[16]

TheSomersett casein 1772, in which a fugitive slave was freed with the judgement that slavery did not exist underEnglish common law,helped launch the British movement to abolish slavery.[17]Though anti-slavery sentiments were widespread by the late 18th century, many colonies and emerging nations continued to useslave labour:Dutch,French,British,Spanish,andPortugueseterritories in the West Indies, South America, and the Southern United States. After theAmerican Revolutionestablished the United States, many Loyalists who fled the Northern United States immigrated to the British province of Quebec, bringing an English majority population as well as many slaves, leading the province to ban the institution in 1793 (seeSlavery in Canada). In the U.S., Northern states,beginning with Pennsylvaniain 1780, passed legislation during the next two decades abolishing slavery, sometimes bygradual emancipation.Vermont, which was excluded from the thirteen colonies, existed as an independent state from 1777 to 1791. Vermont abolished adult slavery in 1777. In other states, such as Virginia, similar declarations of rights were interpreted by the courts as not applicable to Africans and African Americans. During the following decades, the abolitionist movement grew in northern states, and Congress heavily regulated the expansion of Slave or Free States in new territories admitted to the union (seeMissouri compromise).

In 1787, theSociety for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Tradewas formed in London.Revolutionary Franceabolished slavery throughout its empire through theLaw of 4 February 1794,butNapoleonrestored it in 1802as part of a program to ensure sovereignty over its colonies. On March 16, 1792, Denmark became the first country to issue a decree to abolish theirtransatlantic slave tradefrom the start of 1803.[18]However, Denmark would not abolish slavery in the Danish West Indies until 1848.[19]Haiti (then Saint-Domingue) formallydeclared independence from Francein 1804 and became the first nation in theWestern Hemisphereto permanently eliminate slavery in themodern era,following the1804 Haitian massacre.[20]The northern states in the U.S. all abolished slavery by 1804. The United Kingdom (then including Ireland) and the United States outlawed theinternational slave tradein 1807, after which Britain led efforts toblock slave ships.Britain abolished slavery throughout its empire by theSlavery Abolition Act 1833(with the notableexception of India), theFrench coloniesre-abolished it in 1848 and the U.S. abolished slavery in 1865 with the13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Development[edit]

The last known form of enforced servitude of adults (villeinage) had disappeared in England by the beginning of the 17th century. In 1569 a court considered the case of Cartwright, who had bought a slave from Russia. The court ruled English law could not recognize slavery, as it was never established officially. This ruling was overshadowed by later developments; It was upheld in 1700 by the Lord Chief JusticeJohn Holtwhen he ruled that a slave became free as soon as he arrived in England.[21]During theEnglish Civil Warsof the mid-seventeenth century, sectarian radicals challenged slavery and other threats to personal freedom. Their ideas influenced many antislavery thinkers in the eighteenth century.[11]

In addition to English colonists importing slaves to the North American colonies, by the 18th century, traders began to import slaves from Africa, India and East Asia (where they were trading) toLondonandEdinburghto work as personal servants. Men who migrated to the North American colonies often took their East Indian slaves or servants with them, asEast Indianshave been documented in colonial records.[22][23]

Some of the firstfreedom suits,court cases in the British Isles to challenge the legality of slavery, took place in Scotland in 1755 and 1769. The cases wereMontgomery v. Sheddan(1755) andSpens v. Dalrymple(1769). Each of the slaves had been baptized in Scotland and challenged the legality of slavery. They set the precedent of legal procedure in British courts that would later lead to successful outcomes for the plaintiffs. In these cases, deaths of the plaintiff and defendant, respectively, brought an end before court decisions.[24]

African slaves were not bought or sold in London but were brought by masters from other areas. Together with people from other nations, especially non-Christian, Africans were considered foreigners, not able to be English subjects. At the time, England had nonaturalizationprocedure. The African slaves' legal status was unclear until 1772 andSomersett's Case,when the fugitive slave James Somersett forced a decision by the courts. Somersett had escaped, and his master, Charles Steuart, had him captured and imprisoned on board a ship, intending to ship him toJamaicato be resold into slavery. While in London, Somersett had beenbaptized;three godparents issued a writ ofhabeas corpus.As a result,Lord Mansfield,Chief Justice of theCourt of the King's Bench,had to judge whether Somersett's abduction was lawful or not under EnglishCommon Law.No legislation had ever been passed to establish slavery in England. The case received national attention, and five advocates supported the action on behalf of Somersett.

In his judgement of 22 June 1772, Mansfield declared:

The state of slavery is of such a nature that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political, but only by positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasions, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory. It is so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.[25]

Although theexact legal implicationsof the judgement are unclear when analysed by lawyers, the judgement was generally taken at the time to have determined that slavery did not exist under English common law and was thus prohibited in England.[26]The decision did not apply to the British overseas territories; by then, for example, the American colonies had established slavery by positive laws.[27]Somersett's case became a significant part of the common law of slavery in the English-speaking world and it helped launch the movement to abolish slavery.[28]

After reading about Somersett's Case,Joseph Knight,an enslaved African who had been purchased by his master John Wedderburn in Jamaica and brought to Scotland, left him. Married and with a child, he filed afreedom suit,on the grounds that he could not be held as a slave inGreat Britain.In the case ofKnight v. Wedderburn(1778), Wedderburn said that Knight owed him "perpetual servitude". TheCourt of Sessionof Scotland ruled against him, saying thatchattel slaverywas not recognized under thelaw of Scotland,and slaves could seek court protection to leave a master or avoid being forcibly removed from Scotland to be returned to slavery in the colonies.[24]

But at the same time, legally mandated,hereditaryslavery of Scots persons in Scotland had existed from 1606[30]and continued until 1799, whencolliersandsalterswereemancipatedby an act of theParliament of Great Britain(39 Geo. 3.c. 56). Skilled workers, they were restricted to a place and could be sold with the works. A prior law enacted in 1775 (15 Geo. 3.c. 28) was intended to end what the act referred to as "a state of slavery and bondage,"[31]but that was ineffective, necessitating the 1799 act.

In the 1776 bookThe Wealth of Nations,Adam Smithargued for the abolition of slavery on economic grounds. Smith pointed out that slavery incurred security, housing, and food costs that the use of free labour would not, and opined that free workers would be more productive because they would have personal economic incentives to work harder. The death rate (and thus repurchase cost) of slaves was also high, and people are less productive when not allowed to choose the type of work they prefer, are illiterate, and are forced to live and work in miserable and unhealthy conditions. The free labour markets and international free trade that Smith preferred would also result in different prices and allocations that Smith believed would be more efficient and productive for consumers.

British Empire[edit]

Prior to theAmerican Revolution,there were few significant initiatives in the American colonies that led to the abolitionist movement. Some Quakers were active.Benjamin Kentwas the lawyer who took on most of the cases of slaves suing their masters for personal illegal enslavement. He was the first lawyer to successfully establish a slave's freedom.[32]In addition, Brigadier GeneralSamuel Birchcreated theBook of Negroes,to establish which slaves were free after the war.

In 1783, an anti-slavery movement began among the British public to end slavery throughout the British Empire.

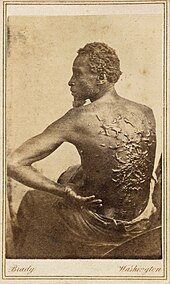

After the formation of theCommittee for the Abolition of the Slave Tradein 1787,William Wilberforceled the cause of abolition through the parliamentary campaign.Thomas Clarksonbecame the group's most prominent researcher, gathering vast amounts of data on the trade. One aspect of abolitionism during this period was the effective use of images such as the famousJosiah Wedgwood"Am I Not A Man and a Brother?"anti-slavery medallion of 1787. Clarkson described the medallion as" promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom ".[33][34]The 1792 Slave Trade Bill passed the House of Commons mangled and mutilated by the modifications and amendments ofPitt,it lay for years, in the House of Lords.[35][36]BiographerWilliam Hagueconsiders the unfinished abolition of the slave trade to be Pitt's greatest failure.[37]TheSlave Trade Actwas passed by theBritish Parliamenton 25 March 1807, making the slave trade illegal throughout the British Empire.[38]Britain used its influence to coerce other countries to agree totreatiesto end their slave trade and allow the Royal Navy toseize their slave ships.[39][40]Britain enforced the abolition of the trade because the act made trading slaves within British territories illegal. However, the act repealed theAmelioration Act 1798which attempted to improve conditions for slaves. The end of the slave trade did not end slavery as a whole. Slavery was still a common practice.

In the 1820s, the abolitionist movement revived to campaign against the institution of slavery itself. In 1823 the first Anti-Slavery Society, theSociety for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the British Dominions,was founded. Many of its members had previously campaigned against the slave trade. On 28 August 1833, theSlavery Abolition Actwas passed. It purchased the slaves from their masters and paved the way for the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire by 1838,[41]after which the first Anti-Slavery Society was wound up.

In 1839, theBritish and Foreign Anti-Slavery Societywas formed byJoseph Sturge,which attempted to outlaw slavery worldwide and also to pressure the government to help enforce the suppression of the slave trade by declaringslave tradersto be pirates. The world's oldest international human rights organization, it continues today asAnti-Slavery International.[42]Thomas Clarkson was the key speaker at theWorld Anti-Slavery Conventionit held in London in 1840.

Moldavia and Wallachia[edit]

In the principalities ofWallachiaandMoldavia,the government held slavery of theRoma(often referred to as Gypsies)as legalat the beginning of the 19th century. The progressive pro-European and anti-Ottoman movement, which gradually gained power in the two principalities, also worked to abolish that slavery. Between 1843 and 1855, the principalities emancipated all of the 250,000 enslaved Roma people.[43]

In the Americas[edit]

Bartolomé de las Casaswas a 16th-centurySpanishDominicanpriest, the first resident Bishop ofChiapas(Central America, today Mexico). As a settler in theNew Worldhe witnessed and opposed the poor treatment and virtual slavery of theNative Americansby the Spanish colonists, under theencomiendasystem. He advocated before KingCharles V, Holy Roman Emperoron behalf of rights for the natives.

Las Casas for 20 years worked to get African slaves imported to replace natives; African slavery was everywhere and no one talked of ridding the New World of it, though France had abolished slavery in France itself and there was talk in other countries about doing the same. However, Las Casas had a late change of heart, and became an advocate for the Africans in the colonies.[44][45]

His book,A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies,contributed to Spanish passage of colonial legislation known as theNew Laws of 1542,which abolished native slavery for the first time in European colonial history. It ultimately led to theValladolid debate,the first European debate about the rights of colonized people.

Latin America[edit]

During the early 19th century, slavery expanded rapidly in Brazil, Cuba, and the United States, while at the same time the new republics of mainland Spanish America became committed to the gradual abolition of slavery. During theSpanish American wars for independence(1810–1826), slavery was abolished in most of Latin America, though it continued until 1873 inPuerto Rico,1886 in Cuba, and 1888 in Brazil (where it was abolished by theLei Áurea,the "Golden Law" ). Chile declaredfreedom of wombsin 1811, followed by theUnited Provinces of the River Platein 1813,ColombiaandVenezuelain 1821, but without abolishing slavery completely. While Chile abolished slavery in 1823, Argentina did so with the signing of theArgentine Constitution of 1853.Peru abolished slavery in 1854. Colombia abolished slavery in 1851. Slavery was abolished in Uruguay during theGuerra Grande,by both the government ofFructuoso Riveraand thegovernment in exileofManuel Oribe.[46]

Canada[edit]

Throughout the growth of slavery in the American South,Nova Scotiabecame a destination for black refugees leaving Southern Colonies and United States. While many blacks who arrived in Nova Scotia during the American Revolution were free, others were not.[48]Black slaves also arrived in Nova Scotia as the property ofWhite AmericanLoyalists. In 1772, prior to the American Revolution, Britaindetermined that slavery could not exist in the British Islesfollowed by theKnight v. Wedderburndecision in Scotland in 1778. This decision, in turn, influenced the colony of Nova Scotia. In 1788, abolitionistJames Drummond MacGregorfrom Pictou published the first anti-slavery literature in Canada and began purchasing slaves' freedom and chastising his colleagues in the Presbyterian church who owned slaves.[49]In 1790John Burbidgefreed his slaves. Led byRichard John Uniacke,in 1787, 1789 and again on 11 January 1808, the Nova Scotian legislature refused to legalize slavery.[50][51]Two chief justices,Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange(1790–1796) andSampson Salter Blowers(1797–1832) were instrumental in freeing slaves from their owners in Nova Scotia.[52][53][54]They were held in high regard in the colony. By the end of theWar of 1812and the arrival of the Black Refugees, there were few slaves left in Nova Scotia.[55]TheSlave Trade Actoutlawed the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807 and theSlavery Abolition Act of 1833outlawed slavery altogether.

With slaves escaping to New York and New England, legislation for gradual emancipation was passed inUpper Canada(1793) andLower Canada(1803). In Upper Canada, theAct Against Slaveryof 1793 was passed by the Assembly under the auspices ofJohn Graves Simcoe.It was the first legislation against slavery in theBritish Empire.Under its provisions no new slaves could be imported, slaves already in the province would remain enslaved until death, and children born to female slaves would be slaves but must be freed at the age of 25. The last slaves in Canada gained their freedom when slavery was abolished in the entire British Empire by the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.[56]

United States[edit]

In his bookThe Struggle For Equality,historianJames M. McPhersondefines an abolitionist "as one who before the Civil War had agitated for the immediate, unconditional, and total abolition of slavery in the United States".[57]He does not include antislavery activists such as Abraham Lincoln or the Republican Party, which called for the gradual ending of slavery.[57]

Benjamin Franklin,a slaveholder for much of his life, became a leading member of thePennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery,the first recognized organization for abolitionists in the United States.[58]Following theAmerican Revolutionary War,Northern states abolished slavery, beginning with the1777 Constitution of Vermont,followed byPennsylvania's gradual emancipation act in 1780.Other states with more of an economic interest in slaves, such as New York and New Jersey, also passed gradual emancipation laws, and by 1804, all the Northern states had abolished it, although this did not mean that already enslaved people were freed. Some had to work without wages as "indentured servants"for two more decades, although they could no longer be sold.

The 1836–1837 campaign to end free speech in Alton, Illinois culminated in the 7 November 1837 mob murder of abolitionist newspaper editorElijah Parish Lovejoy,which was covered in newspapers nationwide, causing a rise in membership in abolitionist societies. By 1840 more than 15,000 people were members of abolitionist societies in the United States.[59]

In the 1850s in the fifteen states constituting theAmerican South,slavery was legally established. While it was fading away in the cities as well as in the border states, it remained strong in plantation areas that grew cotton for export, or sugar, tobacco, or hemp. According to the1860 United States Census,the slave population in the United States had grown to four million.[60]American abolitionism was based in the North, although there were anti-abolitionist riots in several cities. In the South abolitionism was illegal, and abolitionist publications, likeThe Liberator,could not be sent to Southern post offices.Amos Dresser,a white alumnus ofLane Theological Seminary,was publicly whipped inNashville, Tennessee,for possessing abolitionist publications.[61][62]In addition, laws were passed to further repress slaves. These laws included anti-literacy laws and anti-gathering laws. The anti-gathering laws were applied to religious gatherings of free blacks and slaves. These laws, passed around the 1820–1850 period, were blamed in the South on Northern abolitionists. As one slaveowner wrote, "I can tell you. It was the abolition agitation. If the slave is not allowed to read his bible, the sin rests upon the abolitionists; for they stand prepared to furnish him with a key to it, which would make it, not a book of hope, and love, and peace, but of despair, hatred and blood; which would convert the reader, not into a Christian, but a demon. [...] Allow our slaves to read your writings, stimulating them to cut our throats! Can you believe us to be such unspeakable fools?"[63]

Abolitionism in the United States became a popular expression ofmoralism,[64]operating in tandem with other social reform efforts, such as thetemperance movement,[65][66]and much more problematically, thewomen's suffrage movement.

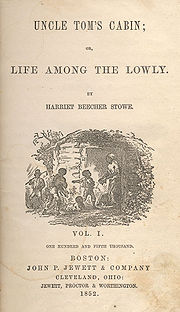

The white abolitionist movement in the North was led by social reformers, especiallyWilliam Lloyd Garrison(founder of theAmerican Anti-Slavery Society) and writersWendell Phillips,John Greenleaf Whittier,andHarriet Beecher Stowe.[67]Black activists included former slaves such asFrederick Douglassand free blacks such as the brothersCharles Henry LangstonandJohn Mercer Langston,who helped found the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society.[68]Some abolitionists said that slavery was criminal and a sin; they also criticized slave owners of using black women asconcubinesand taking sexual advantage of them.[69]

TheRepublican Partywanted to achieve the gradual extinction of slavery by market forces, because its members believed that free labour was superior to slave labour. White southern leaders said that the Republican policy of blocking the expansion of slavery into the West made them second-class citizens, and they also said it challenged their autonomy. With the1860 presidential victoryofAbraham Lincoln,seven Deep South states whose economy was based on cotton and the labour of enslaved people decided to secede and form a new nation. TheAmerican Civil Warbroke out in April 1861 with thefiring on Fort SumterinSouth Carolina.WhenLincoln called for troopsto suppress the rebellion, four more slave states seceded. Meanwhile, four slave states, known as theborder states(Maryland, Missouri, Delaware, and Kentucky), chose to remain in the Union.

Civil War and final emancipation[edit]

On 16 April 1862, Abraham Lincoln signed theDistrict of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act,abolishing slavery in Washington D. C. Meanwhile, the Union suddenly found itself dealing with a steady stream of escaped slaves from the South rushing to Union lines. In response, Congress passed theConfiscation Acts,which essentially declared escaped slaves from the South to be confiscated war property, calledcontrabands,so that they would not be returned to their masters in theConfederacy.Although the initial act did not mention emancipation, the second Confiscation Act, passed on 17 July 1862, stated that escaped or liberated slaves belonging to anyone who participated in or supported the rebellion "shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves." On 1 January 1863, Lincoln issued theEmancipation Proclamation,which was an executive order of the U.S. government that changed the legal status of 3 million slaves in the Confederacy from "slave" to "henceforward... free". Though slaves were legally freed by the Proclamation, they became actually free by escaping to federal lines, or by advances of federal troops. Even before the Emancipation Proclamation, many former slaves served the federal army as teamsters, cooks, laundresses, and laborers, as well as scouts, spies, and guides. Confederate General Robert Lee once said, "The chief source of information to the enemy is through our negroes."[70]The Emancipation Proclamation, however, provided that people it declared to be free who were "of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States", and theUnited States Colored Troopswere formed.

Plantation owners sometimes moved the Black people they claimed to own as far as possible out of reach of the Union army.[71]By "Juneteenth"(19 June 1865, in Texas), the Union Army controlled all of the Confederacy and liberated all its slaves. The owners were never compensated; nor were freed slaves compensated by former owners.[72][73]

The border states were exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation, but they too (except Delaware) began their own emancipation programs.[74]As the war dragged on, both the federal government and Union states continued to take measures against slavery. In June 1864, theFugitive Slave Act of 1850,which required free states to aid in returning escaped slaves to slave states, was repealed. The state of Maryland abolished slavery on 13 October 1864. Missouri abolished slavery on 11 January 1865.West Virginia,which had been admitted to the Union in 1863 as a slave state, but on the condition of gradual emancipation, fully abolished slavery on 3 February 1865. The13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitutiontook effect in December 1865, seven months after the end of the war, and finally ended slavery for non-criminals throughout the United States. It also abolished slavery among the Indian tribes, including the Alaska tribes that became part of the U.S. in 1867.[75]

Cuba and Brazil[edit]

Brazil and Cuba were the last countries in the Western world to abolish slavery, with Brazil being the last in 1888. While actors likeGertrudis Gómez de Avellanedain Brazil andAdelina Charuteirain Cuba worked to end slavery, it was enslaved people themselves who worked daily to chip away at enslavers’ local authority.[76]These actions have at times been dismissed because they were small actions, but historian Adriana Chira argues that while “These freedoms were patchwork, often incomplete when measured against liberal - abolitionist yardsticks, precarious and even reversible” the action “... were very concrete, and in the long term, they served to corrode the legal structures of plantation slavery locally.”[76]These actions included marronage and maroon societies that undermined the authority of enslavers in Brazil and legal challenges relying on the legal history of Spain in Cuba. These practices are regionally specific based on the legal customs of the region that enslaved people knew well from centuries of interactions with Iberian slave laws. A key avenue for these legal arguments was the prominence of “lo extrajudicial,” a field of legal interactions adjacent to a lawsuit explained by historian Bianca Premo as consisting of out-of-court settlements, public revelations, and face-to-face encounters.[77][76](Chira, 29).

Women and Abolitionism[edit]

The suffering of women in slavery was a common trope consistently used in abolitionists’ rhetoric on both sides of the Atlantic. This was especially true as it relates to the image of suffering mothers and their children. Towards the end of the nineteenth century as slavery was coming to an end throughout the Atlantic world, images appearing in abolitionist publications routinely included images of families being torn apart and pregnant women being forced to do hard labor. As countries imposed “free womb laws” to soften the image of slavery and bring about gradual emancipation, for many it raised the question of the justice of women being used to carry out emancipation without benefiting from it themselves. Speeches given on the topic at the time focused on mothers and compared them to “all other mothers,” using motherhood to level the subjects and objects of their speech.[78][79]

Women were also often on the forefront of the abolition movement. Authors such as Harriet Beecher Stowe (United States) andGertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda(Brazil) used their novels to call into question the humanity of slavery. Women such as theGrimké Sisters,Abigail Adams,Elizabeth Cady Stantonand others used their connections to political movements to advocate for the abolition of slavery. Enslaved women such asPhillis Wheatleyand Harriet Tubman took matters into their own hands by challenging the institution of slavery through their writing and their actions.[80]In countries like Cuba and Brazil, where many enslaved women in urban areas were close to the governmental apparatuses needed to challenge slavery, they often used this proximity to pay for their and their families freedom and argued before colonial courts for their freedom with increasing success as the nineteenth century progressed.[78]Enslaved women like Adelina Charuteira used their mobility as street vendors and as much access as they had to literacy to spread information about abolition between freedom-seeking people and local abolitionist networks.[81]

Notable abolitionists[edit]

White and black opponents of slavery, who played a considerable role in the movement. This list includes some escaped slaves, who were traditionally called abolitionists.

- John Quincy Adams

- Abigail Adams

- Lydia Maria Child

- Prudence Crandall

- Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda

- Adelina Charuteira

- Phillis Wheatley

- Angelina Grimke

- Sarah Grimke

- Jeremy Bentham

- Benjamin Lay

- James McCune Smith

- John Brown

- William Wells Brown

- Oren Burbank Cheney

- Thomas Clarkson

- Ellen and William Craft

- Frederick Douglass

- Sarah Mapps Douglass

- Henry Dundas[a]

- John Gregg Fee

- Henry Highland Garnet

- William Lloyd Garrison

- Elijah P. Lovejoy

- Abbé Grégoire

- Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

- Johns Hopkins

- Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil

- John Laurens

- Toussaint Louverture

- Solomon Northup

- Harriet Martineau

- John Stuart Mill

- Charles Miner

- Joaquim Nabuco

- Daniel O'Connell

- José do Patrocínio

- William B. Preston

- André Rebouças

- Granville Sharp

- Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh

- Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Henry David Thoreau

- Sojourner Truth

- Harriet Tubman

- Nat Turner

- David Walker

- William Wilberforce[b]

- John Woolman

Abolitionist publications[edit]

United States[edit]

- The Emancipator(1819–20): founded inJonesboro, Tennesseein 1819 byElihu Embreeas theManumission Intelligencier,The Emancipatorceased publication in October 1820 due to Embree's illness. It was sold in 1821 and becameThe Genius of Universal Emancipation.

- Genius of Universal Emancipation(1821–39): anabolitionistnewspaper published and edited byBenjamin Lundy.In 1829 it employedWilliam Lloyd Garrison,who would go on to createThe Liberator.

- The Liberator(1831–65): a weekly newspaper founded byWilliam Lloyd Garrison.

- The Emancipator(1833–50): different fromThe Emancipatorabove. Published in New York and later Boston.

- The Slave's Friend(1836–38): an anti-slavery magazine for children produced by theAmerican Anti-Slavery Society(AASS).

- The Philanthropist(1836–37): newspaper published in Ohio for and owned by theAnti-Slavery Society.

- The Liberty Bell, by Friends of Freedom(1839–58): an annualgift bookedited and published byMaria Weston Chapman,to be sold or gifted to participants in the anti-slavery bazaars organized by theBoston Female Anti-Slavery Society.

- National Anti-Slavery Standard(1840–70): the official weekly newspaper of theAmerican Anti-Slavery Society,the paper published continuously until the ratification of theFifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitutionin 1870.

- The Unconstitutionality of Slavery(1845): apamphletbyLysander Spooneradvocating the view that theU.S. Constitutionprohibited slavery.

- The Anti-Slavery Bugle(1845–1861): a newspaper published inNew LisbonandSalem,Columbiana County,Ohio,and distributed locally and across the mid-west, primarily toQuakers.

- The National Era(1847–60): a weekly newspaper which featured the works ofJohn Greenleaf Whittier,who served as associate editor, and first published, as a serial,Harriet Beecher Stowe'sUncle Tom's Cabin(1851).

- North Star(1847–51): an anti-slavery American newspaper published by the escaped slave, author, and abolitionist,Frederick Douglass.

International[edit]

- Slave narratives,books published in the U.S. and elsewhere by former slaves or about former slaves, relating their experiences.

- Anti-Slavery International publications

- Voice of the Fugitive(1851–1853): one of the first black newspapers in Upper Canada aimed at fugitive and escaped slaves from the United States. Written byHenry Bibb,an escaped slave who also published his own slave narrative. Published biweekly.

- Provincial Freeman(March 1853–June 1857): a weekly newspaper published by free Black American ex-patriates in Canada,Mary Ann Shaddand others.

- Voice of the Bondsman(1856–1857): a small run two-issue newspaper published by John James Linton, a sympathizing white Canadian.[84][85]

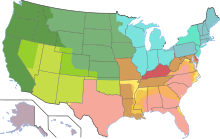

National abolition dates[edit]

International abolitionism[edit]

The first international attempt to address the abolition of slavery was theWorld Anti-Slavery Convention,organised by theBritish and Foreign Anti-Slavery Societyat Exeter Hall in London, on 12–23 June 1840. This was however an attempt made by NGOs, not by state and governments. In the late 19th century, the issue was addressed on an international level by states and governments. TheBrussels Anti-Slavery Conference 1889–90addressed slavery on a semi-global level via the representatives of the colonial powers. It had concluded with theBrussels Conference Act of 1890.The 1890 Act was revised by theConvention of Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1919.

During the 20th century the issue of slavery was addressed by theLeague of Nations,which founded commissions to investigate and eradicate the institution of slavery and slave trade worldwide. TheTemporary Slavery Commission(TSC), which was founded in 1924, conducted a global investigation and filed a report, and a convention was drawn up to hasten the total abolition of slavery and the slave trade.[86] The1926 Slavery Convention,which was founded upon the investigation of the TSC of theLeague of Nations,was a turning point in banning global slavery.

In 1932, the League formed theCommittee of Experts on Slavery(CES) to review the result and enforcement of the 1926 Slavery Convention, which resulted in a new international investigation under the first permanent slavery committee, theAdvisory Committee of Experts on Slavery(ACE).[87] The ACE conducted a major international investigation on slavery and slave trade, inspecting all the colonial empires and the territories under their control between 1934 and 1939.

Article 4 of theUniversal Declaration of Human Rights,adopted in 1948 by theUN General Assembly,explicitly banned slavery. AfterWorld War II,chattel slaverywas formally abolished by law in almost the entire world, with the exception of the Arabian Peninsula and some parts of Africa. Chattel slavery was still legalin Saudi Arabia,in Yemen,inthe Trucial Statesandin Oman,and slaves were supplied to the Arabian Peninsula via theRed Sea slave trade.

When the League of Nations was succeeded by theUnited Nations(UN) afterWorld War II,Charles Wilton Wood Greenidgeof theAnti-Slavery Internationalworked for the UN to continue the investigation of global slavery conducted by the ACE of the League, and in February 1950 the Ad hocCommittee on Slaveryof the United Nations was inaugurated,[88]which ultimately resulted in the introduction of theSupplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery.[89]

TheUnited Nations 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slaverywas convened to outlaw and ban slavery worldwide, includingchild slavery. In November 1962,Faisal of Saudi Arabiafinally prohibited the owning of slaves in Saudi Arabia, followed by the abolition ofslavery in Yemenin 1962,slavery in Dubai1963 andslavery in Omanin 1970.

In December 1966, the UN General Assembly adopted theInternational Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,which was developed from theUniversal Declaration of Human Rights.Article 4 of this international treaty bans slavery. The treaty came into force in March 1976 after it had been ratified by 35 nations.

As of November 2003, 104 nations had ratified the treaty. However, illegal forced labour involves millions of people in the 21st century, 43% for sexual exploitation and 32% for economic exploitation.[90]

In May 2004, the 22 members of theArab Leagueadopted theArab Charter on Human Rights,which incorporated the 1990Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam,[91]which states:

Human beings are born free, and no one has the right to enslave, humiliate, oppress or exploit them, and there can be no subjugation but to God the Most-High.

— Article 11, Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, 1990

Currently, the Anti-trafficking Coordination Team Initiative (ACT Team Initiative), a coordinated effort between theU.S. Departments of Justice,Homeland Security,andLabor,addresses human trafficking.[92]TheInternational Labour Organizationestimates that there are 20.9 million victims of human trafficking globally, including 5.5 million children, of which 55% are women and girls.[93]

After abolition[edit]

In societies with large proportions of the population working in conditions of slavery or serfdom, stroke-of-the-pen laws declaring abolition can have thorough-going social, economic and political consequences. Issues ofcompensation/redemption,land-redistributionand citizenship can prove intractable. For example:

- Haiti,which effectively achieved abolition due toslave revolt and revolution(1792–1804), struggled to overcome racial or anti-revolutionary prejudice in the international financial and diplomatic scene, andexchanged unequal prosperity for relative poverty.One major cause of Haiti's enduring poverty is theHaiti Independence Debt[94][95]France forced on Haiti as "compensated emancipation"for emancipation in 1825 and which (including secondary debts and interests) was not paid off until 1947.[96]

- Russia's emancipation of its serfsin 1861 failed to allay rural and industrial unrest, which played a part in fomenting therevolutions of 1917.

- The United States achieved freedom for its slaves in 1865 with the ratification of the13th Amendmenton 6 December of that year but faced ongoing slavery-associated racial issues (Jim Crow system,civil-rights struggles,penal labor in the United States).

- Queenslanddeported most of itsblackbirdedPacific Islander labour-force in 1901–1906.

Commemoration[edit]

People in modern times have commemorated abolitionist movements and the abolition of slavery in different ways around the world. The United Nations General Assembly declared 2004 theInternational Year to Commemorate the Struggle against Slavery and its Abolition.This proclamation marked the bicentenary of the proclamation of the first modern slavery-free state, Haiti. Numerous exhibitions, events and research programmes became associated with the initiative.

2007 witnessed major exhibitions in British museums and galleries to mark the anniversary of the 1807 abolition act – 1807 Commemorated[97]2008 marked the 201st anniversary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade in the British Empire.[98]It also marked the 175th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the British Empire.[99]

The Faculty of Law at theUniversity of Ottawaheld a major international conference entitled, "Routes to Freedom: Reflections on the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade", from 14 to 16 March 2008.[100]

American abolitionist constitutionalism[edit]

Abolitionist constitutionalism is a line of thinking which invokes the historical view of theConstitution of the United Statesas an abolitionist document. It calls for an appeal to constitutionalism and progressive constitutionalism.[101]This vision is interdisciplinary and finds its roots in the anti-slavery movement in the United States of America and is largely based on the tenet that current state institutions, particularly the carceral system, is rooted in the transatlantic slave trade. Some constitutional abolitionists critique the claim that the Constitution was pro-slavery.[102]

Radical abolitionist constitutionalism calls for the idea of dignity and the use of jurisprudence to address social inequalities.[103]

Whereas the original U.S. Constitution was pro-slavery, theReconstruction Amendmentscan be seen as a compromise for freedom, without allowing for the full abolition. Criminal punishment was a major way that Southern states maintained the exploitation of black labour and effectively nullified the Reconstruction Amendments. This was done namely through Black Codes, harsh vagrancy laws, apprenticeship laws and extreme punishment for black people.[101]The Reconstruction Amendments in their aim to promote citizenship and emancipation are believed by these thinkers to still be guiding principles in the fight for freedom and abolition.

There are suggestions that a broad reading of theThirteenth Amendmentcan convey an abolitionist vision of the freedom advocated for by black people in the public sphere beyond emancipation.[104]

Section one of theFourteenth Amendmentwas used by many abolitionist lawyers and activists throughout the North to advance the case against slavery.[102]

Proponents of abolitionist constitutionalism believe the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments can be used today to extend the abolitionist logics to the various current barriers to injustices that are faced by marginalized peoples.[103]

Just like abolitionism more generally, abolitionist constitutionalism seeks to provide a vision which will lead to the abolition of many different neoliberal state institutions, such as theprison industrial complex,the wage system, and policing. This is tied to a belief that white supremacy is woven into the fabric of legal state institutions.[101]

Radical abolitionists are often marginalized. There is a belief that constitutionalism as a main tenet of radical abolitionism can change and appeal to the popular opinion more.[103]Historically, slavery abolitionists have had to use the public meaning of Constitutional terms in order in their fight against slavery.[102]Constitutional abolitionists are generally in favour of incremental changes that follow the principles of the Reconstructive Amendments.[101]

There are debates among abolitionists, where some claim that the Constitution ought not to be treated as an abolitionist text, as it is rather used as a legal tool by the state to deny freedoms to marginalized communities; and that contemporary abolitionist work cannot be done by relying on the constitutional texts. Some argue that the narrative and scholarly literature around Reconstruction Amendments is not coherent regarding their original aims.[101]

Contemporary abolitionism[edit]

On 10 December 1948, theGeneral Assemblyof the United Nations adopted theUniversal Declaration of Human Rights.Article 4 states:

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.

Although outlawed in most countries, slavery is nonetheless practised secretly in many parts of the world. Enslavement still takes place in theUnited States,Europe, and Latin America,[105]as well as parts of Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia.[106]Modern slavery keeps around 50 million people from exercising their freedom.[107]In Mauritania alone, estimates are that up to 600,000 men, women and children, or 20% of the population, are enslaved. Many of them are used asbonded labour.[108]

Modern-day abolitionists have emerged over the last several years, as awareness of slavery around the world has grown, with groups such asAnti-Slavery International,theAmerican Anti-Slavery Group,International Justice Mission,andFree the Slavesworking to rid the world of slavery.[109]

In the United States, The Action Group to End Human Trafficking and Modern-Day Slavery is a coalition of NGOs,foundationsand corporations working to develop a policy agenda for abolishing slavery and human trafficking. Since 1997, theUnited States Department of Justicehas, through work with theCoalition of Immokalee Workers,prosecuted six individuals in Florida on charges of slavery in the agricultural industry. These prosecutions have led to freedom for over 1000 enslaved workers in the tomato and orange fields of South Florida. This is only one example of the contemporary fight against slavery worldwide. Slavery exists most widely in agricultural labour, apparel and sex industries, and service jobs in some regions.[110]

In 2000, the United States passed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (TVPA) "to combat trafficking in persons, especially into the sex trade, slavery, and involuntary servitude."[111]The TVPA also "created new law enforcement tools to strengthen the prosecution and punishment of traffickers, making human trafficking a Federal crime with severe penalties."[112]

In 2014, for the first time in history major Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox Christian leaders, as well as Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist leaders, met to sign a shared commitment against modern-day slavery; the declaration they signed calls for the elimination of slavery and human trafficking by 2020.[113]

TheUnited States Department of Statepublishes the annual Trafficking in Persons Report, identifying countries as either Tier 1, Tier 2, Tier 2 Watch List or Tier 3, depending upon three factors: "(1) The extent to which the country is a country of origin, transit, or destination for severe forms of trafficking; (2) The extent to which the government of the country does not comply with the TVPA's minimum standards including, in particular, the extent of the government's trafficking-related corruption; and (3) The resources and capabilities of the government to address and eliminate severe forms of trafficking in persons."[115]

The 13th amendment abolished slavery in the United States "except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted."[116]In 2018, Colorado became the first state to remove similar language in its state constitution by alegislatively referredballot referendum.[117][118][114]Other states have followed suit, but implementation has relied on court rulings.[119]

See also[edit]

- Abolitionism (disambiguation),other movements to address perceived social ills, such as thePrison abolition movement

- Anti-Slavery Society (disambiguation),various organisations referred to by this name

- Compensated emancipation

- History of slavery

- List of abolitionist forerunners

- London Society of West India Planters and Merchants,a lobby group representing slave owners

- Monumento a la abolición de la esclavitud,in Puerto Rico

- Representation of slavery in European art

- Slavery in the British and French Caribbean

- Timeline of abolition of slavery and serfdom

Organisations and commemorations[edit]

- International Day for the Abolition of Slavery

- International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition

References and notes[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^Henry Dundas achieved the first victory in the House of Commons for the abolition of the Atlantic Slave Trade in 1792.

- ^Wilberforce was a leader of the abolitionism movement. He was an English politician who became a Member of Parliament. His involvement in the political realm lead to a change in ideology.

Citations[edit]

- ^"Slavery's last stronghold",CNN. March 2012.

- ^"The Life of St. Eligius".Medieval Sourcebook. Translated by Jo Ann McNamara. Fordham University.Retrieved2 December2011.

- ^Schulenburg, Jane.Forgetful of their Sex: Female Sanctity and Society, ca. 500–1100,Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998

- ^Christopher L. Miller,The French Atlantic Triangle: literature and culture of the slave trade,Duke University Press, p. 20.

- ^Malick W. Ghachem,The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution,Cambridge University Press, p. 54.

- ^Chatman, Samuel L. (2000). "'There Are No Slaves in France': A Re-Examination of Slave Laws in Eighteenth Century France ".The Journal of Negro History.85(3): 144–153.doi:10.2307/2649071.JSTOR2649071.S2CID141017958.

- ^Rodney Stark,For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-hunts, and the End of Slavery,Princeton University Press, 2003, p. 322. There was typo in the original hardcover stating "31.2 percent"; this was corrected to 13.2% in the paperback edition and can be verified using 1830 census data.

- ^Samantha Cook, Sarah Hull (2011).The Rough Guide to the USA.Rough Guides UK.ISBN978-1-4053-8952-5.

- ^abTerry L. Jones (2007).The Louisiana Journey.Gibbs Smith.ISBN978-1-4236-2380-9.

- ^Martin H. Steinberg; Bernard G. Forget; Douglas R. Higgs; Ronald L. Nagel (2001).Disorders of Hemoglobin: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management.Cambridge University Press. pp. 725–726.ISBN978-0-521-63266-9.

- ^abDi Lorenzo, A; Donoghue, J; et al. (2016),"Abolition and Republicanism over the Transatlantic Long Term, 1640–1800",La Révolution Française(11),doi:10.4000/lrf.1690

- ^Dubois, Laurent (2004).Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution.Harvard University Press. pp. 91–114.ISBN978-0-674-03436-5.OCLC663393691.

- ^Popkin, Jeremy D. (2010).You Are All Free: The Haitian Revolution and the Abolition of Slavery.Cambridge University Press. pp. 246–375.ISBN978-0-521-51722-5.

- ^Geggus, David (2014).The Haitian Revolution: A Documentary History.Hackett Publishing.ISBN978-1-62466-177-8.

- ^Popkin, J. (2010) You are all Free. The Haitian Revolution and the Abolition of Slavery, pp. 350–70, 384, 389.

- ^Wilson, Thomas,The Oglethorpe Plan,201–206.

- ^Wise, Steven M.,Though the Heavens May Fall: The Landmark Trial that Led to the End of Human Slavery,Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 2005.

- ^"Denmark Abolishes Slavery".

- ^"The Abolition of Slavery in 1848".

- ^"Haiti was the first nation to permanently ban slavery".Gaffield, Julia.Retrieved15 July2020.

- ^V.C.D. Mtubani,"African Slaves and English Law",PULA Botswana Journal of African Studies,Vol. 3, No. 2, November 1983. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^Paul Heinegg,Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware,1999–2005,"Weaver Family: Three members of the Weaver family, probably brothers, were called 'East Indians' in Lancaster County, [VA] [court records] between 1707 and 1711." "'The indenture of Indians (Native Americans) as servants was not common in Maryland... the indenture of East Indian servants was more common." Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^Francis C. Assisi,"First Indian-American Identified: Mary Fisher, Born 1680 in Maryland"[usurped],IndoLink, Quote: "Documents available from American archival sources of the colonial period now confirm the presence of indentured servants or slaves who were brought from the Indian subcontinent, via England, to work for their European American masters." Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ab"Slavery, freedom or perpetual servitude? – the Joseph Knight case".National Archives of Scotland.Archived fromthe originalon 27 September 2011.Retrieved27 November2010.

- ^Frederick Charles Moncrieff,The Wit and Wisdom of the Bench and Bar,The Lawbook Exchange, 2006, pp. 85–86.

- ^Mowat, Robert Balmain,History of the English-Speaking Peoples,Oxford University Press, 1943, p. 162.

- ^MacEwen, Martin,Housing, Race and Law: The British Experience,Routledge, 2002, p. 39.

- ^Peter P. Hinks, John R. McKivigan, R. Owen Williams,Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition,Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007, p. 643.

- ^Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840,Benjamin Robert Haydon,1841, London, Given byBritish and Foreign Anti-Slavery Societyin 1880

- ^Brown, K.M.; et al., eds. (2007)."Regarding colliers and salters (ref: 1605/6/39)".The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707.St. Andrews:University of St. Andrews.Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2011.Retrieved6 August2009.

- ^May, Thomas Erskine(1895)."Last Relics of Slavery".The Constitutional History of England (1760–1860).Vol. II. New York: A.C. Armstrong and Son. pp. 274–275.

- ^Blanck, Emily (2014).Forging an American Law of Slavery in Revolutionary South Carolina and Massachusetts.University of Georgia Press. p. 35.ISBN9780-820338644.

- ^"Wedgwood".Archived fromthe originalon 8 July 2009.Retrieved12 August2015.

Thomas Clarkson wrote of the medallion; promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom.

- ^Elizabeth Mcgrath and Jean Michel Massing (eds),The Slave in European Art: From Renaissance Trophy to Abolitionist Emblem,London, 2012.

- ^"Parliamentary History".Corbett. 1817. p. 1293.

- ^"Journal of the House of Lords".H.M. Stationery Office 1790. 1790. p. 391 to 738.

- ^Hague 2005,p. 589

- ^Clarkson, T.,History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade by the British Parliament,London, 1808.

- ^Falola, Toyin; Warnock, Amanda (2007).Encyclopedia of the middle passage.Greenwood Press. pp. xxi, xxxiii–xxxiv.ISBN978-0-313-33480-1.

- ^"William Loney RN – Background".www.pdavis.nl.

- ^Mary Reckord, "The Colonial Office and the Abolition of Slavery."Historical Journal14, no. 4 (1971): 723–734.online.

- ^Anti-Slavery InternationalUNESCO. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^Viorel Achim (2010). "Romanian Abolitionists on the Future of the Emancipated Gypsies",Transylvanian Review,Vol. XIX, Supplement no. 4, 2010, p. 23.

- ^"Columbus 'sparked a genocide'".BBC News.12 October 2003.

- ^Blackburn 1997: 136; Friede 1971: 165–166. Las Casas' change in his views on African slavery is expressed particularly in chapters 102 and 129, Book III of hisHistoria.

- ^Peter Hinks and John McKivigan, eds.Abolition and Antislavery: A Historical Encyclopedia of the American Mosaic(2015).

- ^The portrait is now at the National Gallery of Scotland. According to Thomas Akins, this portrait hung in the legislature ofProvince House (Nova Scotia)in 1847 (seeHistory of Halifax,p. 189).

- ^Slavery in the Maritime Provinces.The Journal of Negro History. July 1920.

- ^"Biography – MacGregor James Drummond – Volume VI (1821–1835) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography".biographi.ca.

- ^Bridglal Pachai & Henry Bishop.Historic Black Nova Scotia,2006, p. 8.

- ^John Grant.Black Refugees,p. 31.

- ^"Biography – Strange, Sir Thomas Andrew Lumisden – Volume VII (1836–1850) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography".www.biographi.ca.

- ^"Celebrating the 250th Anniversary of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia".courts.ns.ca.Archived fromthe originalon 12 January 2015.Retrieved1 February2015.

- ^Barry Cahill, "Slavery and the Judges of Loyalist Nova Scotia",UNB Law Journal,43 (1994), pp. 73–135.

- ^"Nova Scotia Archives – African Nova Scotians".novascotia.ca.20 April 2020.

- ^Robin Winks,Blacks in Canada: A History(1971).

- ^abJames M. McPherson(1995).The Abolitionist Legacy: From Reconstruction to the NAACP.Princeton University Press. p.4.ISBN978-0-691-10039-5.

- ^Seymour Stanton Black.Benjamin Franklin: Genius of Kites, Flights, and Voting Rights.

- ^The Young people's encyclopedia of the United States.Shapiro, William E. Brookfield, Conn.: Millbrook Press. 1993.ISBN1-56294-514-9.OCLC30932823.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^Introduction – Social Aspects of the Civil WarArchived14 July 2007 at theWayback Machine,National Park Service.

- ^Dresser, Amos (26 September 1835)."Amos Dresser's Own Narrative".The Liberator.p. 4 – via newspapers.com.

- ^"Amos Dresser's Case".Evening Post.17 September 1835. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- ^Cunningham, Jerry (2023).The Alphabet as Resistance: Laws Against Reading, Writing and Religion in the Slave South.Portland, Oregon: Independently Published. pp. 116–117.ISBN9798390042335.

- ^Robins, R.G. (2004).A. J. Tomlinson: Plainfolk Modernist.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-988317-2.

- ^Finkelman, Paul(2006).Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619–1895.Oxford University Press, US. p. 228.ISBN978-0-19-516777-1.

These and other African American temperance activists – includingJames W. C. Pennington,Robert Purvis,William Watkins,William Whipper,Samuel Ringgold Ward,Sarah Parker Remond,Frances E. Watkins Harper,William Wells Brown,andFrederick Douglass– increasingly linked temperance to a larger battle against slavery, discrimination, and racism. In churches, conventions, and newspapers, these reformers promoted an absolute and immediate rejection of both alcohol and slavery. The connection between temperance and antislavery views remained strong throughout the 1840s and 1850s. The white abolitionistsArthur TappanandGerrit Smithhelped lead the American Temperance Union, formed in 1833. Frederick Douglass, who took the teetotaler pledge while in Scotland in 1845, claimed, "I am a temperance man because I am an anti-slavery man." Activists argued that alcohol aided slavery by keeping enslaved men and women addled and by sapping the strength of free black communities.

- ^Venturelli, Peter J.; Fleckenstein, Annette E. (2017).Drugs and Society.Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 252.ISBN978-1-284-11087-6.

Because the temperance movement was closely tied to the abolitionist movement as well as to the African American church, African Americans were preeminent promoters of temperance.

- ^Smith, George H.(2008)."Abolitionism".InHamowy, Ronald(ed.).The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism.Thousand Oaks, CA:SAGE Publications,Cato Institute.pp. 1–2.doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n1.ISBN978-1412965804.LCCN2008009151.OCLC750831024.

- ^Leon F. LitwackandAugust Meier,eds., "John Mercer Langston: Principle and Politics", inBlack Leaders of the 19th Century,University of Illinois Press, 1991, pp. 106–111

- ^James A. Morone(2004).Hellfire Nation: The Politics of Sin in American History.Yale University Press. p. 154.ISBN978-0-300-10517-9.

- ^"African Americans in The Civil War".HistoryNet.Retrieved24 July2021.

- ^Leon F. Litwack,Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery(1979), pp. 30–36, 105–166.

- ^Michael Vorenberg, ed.,The Emancipation Proclamation: A Brief History with Documents(2010).

- ^Peter Kolchin, "Reexamining Southern Emancipation in Comparative Perspective,"Journal of Southern History,81#1 (February 2015), 7–40.

- ^Foner, Eric; Garraty, John A."Emancipation Proclamation".History Channel.Retrieved13 October2014.

- ^Vorenberg,Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment(2004).

- ^abcChira, Adriana (2022).Patchwork Freedoms: Law, Slavery, and Race beyond Cuba's Plantations.Cambridge: Cambrisge University Press. pp. 4, 29.ISBN978-1108499545.

- ^Premo, Bianca (2019). "Lo extrajudicial: Between Court and Community in the Spanish Empire". In Vermeesch, Griet (ed.).The Uses of Justice in Global Perspective, 1600–1900.New York: Routledge. pp. 183–197.

- ^abCowling, Camillia (4 October 2011)."'As a slave woman and as a mother': women and the abolition of slavery in Havana and Rio de Janeiro ".Social History.36(3): 294–311.doi:10.1080/03071022.2011.598728.

- ^"A emancipação na tribuna sagrada'".O Abolicionista [The Abolitionist].1 January 1881. pp. 7–8.

- ^McCutcheon, Roberta."Woman Abolitionists".The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

- ^Acerbi, Patricia."Stories / Adelina Charuteira".Enslaved: Peoples of Historical Slave Trade.Retrieved17 May2024.

- ^"How Sojourner Truth Used Photography to Help End Slavery".

- ^"Why Abolitionist Frederick Douglass Loved the Photograph".4 December 2015.

- ^"Western News - Western rediscovers, revives long-lost abolitionist newspaper".Western News.21 August 2019.Retrieved28 October2022.

- ^Linton, J. J. E."Voice of the Bondsman".news.ourontario.ca.Retrieved28 October2022.

- ^Miers, Suzanne (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. USA: AltaMira Press, pp. 100–121

- ^Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 216

- ^Miers, Suzanne (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press, pp. 323-324

- ^Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 326

- ^David P. Forsythe, ed. (2009).Encyclopedia of human rights.Oxford University Press. pp. 494–502.ISBN978-0195334029.

- ^"Slavery in Islam".BBC.co.uk.BBC.Retrieved6 October2015.

- ^McKee, Caroline (7 July 2015)."U.S. works to fight modern-day slavery".Retrieved21 July2015.

- ^"Human Trafficking".polarisproject.org.Archived fromthe originalon 21 July 2015.Retrieved21 July2015.

- ^Gamio, Lazaro; Méheut, Constant; Porter, Catherine; Gebrekidan, Selam; McCann, Allison; Apuzzo, Matt (20 May 2022)."Haiti's Lost Billions".The New York Times.

- ^Porter, Catherine; Méheut, Constant; Apuzzo, Matt; Gebrekidan, Selam (20 May 2022)."The Root of Haiti's Misery: Reparations to Enslavers".The New York Times.

- ^"France dismisses petition for it to pay $17 billion in Haiti reparations".Christian Science Monitor.

- ^"1807 Commemorated".Institute for the Public Understanding of the Past and the Institute of Historical Research. 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 26 December 2010.Retrieved27 November2010.

- ^"Slave Trade Act 1807 UK".anti-slaverysociety.addr.com. Archived fromthe originalon 13 May 2008.Retrieved16 April2008.

- ^"Slavery Abolition Act 1833 UK".anti-slaverysociety.addr.com. Archived fromthe originalon 29 April 2008.Retrieved16 April2008.

- ^ "Les Chemins de la Liberté: Réflexions à l'occasion du bicentenaire de l'abolition de l'esclavage / Routes to Freedom: Reflections on the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade".University of Ottawa,Canada. Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2011.Retrieved27 November2010.

- ^abcdeRoberts, Dorothy (2019)."Abolition Constitutionalism".Harvard Law Review.133(1).

- ^abcBarnett, Randy E.(2011)."Whence Comes Section One? The Abolitionist Origins of the Fourteenth Amendment".Journal of Legal Analysis.3(1): 165–263.doi:10.1093/jla/3.1.165.ISSN1946-5319.

- ^abcMalkani, Bharat (16 May 2018).Slavery and the Death Penalty: A Study in Abolition(1 ed.). New York, NY: Routledge, 2018. | Series: Law, justice and power: Routledge.doi:10.4324/9781315609300.ISBN978-1-315-60930-0.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location (link) - ^Fox, James (2021). "The Constitution of Black Abolitionism: Re-Framing the Second Founding".University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law.23(2).

- ^Bales, Kevin.Ending Slavery: How We Free Today's Slaves.University of California Press, 2007,ISBN978-0-520-25470-1.

- ^"Does Slavery Still Exist?"Archived6 April 2007 at theWayback MachineAnti-Slavery Society.

- ^"How we work to end slavery".Anti-Slavery International. Archived fromthe originalon 19 March 2023.

- ^"Mauritanian MPs pass slavery law".BBC News.9 August 2007.

- ^Epps, Henry.A Concise Chronicle History of the African-American People Experience in America.p. 146.

- ^Barnes, Kathrine Lynn; Bendixsen, Casper G. (2 January 2017)."'When This Breaks Down, It's Black Gold': Race and Gender in Agricultural Health and Safety ".Journal of Agromedicine.22(1): 56–65.doi:10.1080/1059924X.2016.1251368.ISSN1059-924X.PMC10782830.PMID27782783.S2CID4251094.

- ^"Public Law 106–386 – 28 October 2000, Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000"(PDF).

- ^US Department of Health and Human ServicesArchived10 September 2008 at theWayback Machine,TVPA Fact Sheet.

- ^Belardelli, Giulia (2 December 2014)."Pope Francis And Other Religious Leaders Sign Declaration Against Modern Slavery".The Huffington Post.

- ^abRadde, Kaitlyn (17 November 2022)."Louisiana voters rejected an antislavery ballot measure. The reasons are complicated".NPR.

- ^"US Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report 2008, Introduction".state.gov. 10 June 2008.

- ^"Constitution of the United States".

- ^"5 states to decide on closing slavery loopholes in voter referendums".PBS NewsHour.20 October 2022.Retrieved19 October2023.

- ^Chappell, Bill (7 November 2018)."Colorado Votes To Abolish Slavery, 2 Years After Similar Amendment Failed".NPR.

- ^Rios, Edwin (24 December 2022)."Movement grows to abolish US prison labor system that treats workers as 'less than human'".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved19 October2023.

Sources[edit]

- Hague, William(2005).William Pitt the Younger.HarperPerennial.ISBN978-0-00-714720-5.

Further reading[edit]

- Bader-Zaar, Birgitta,"Abolitionism in the Atlantic World: The Organization and Interaction of Anti-Slavery Movements in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries",European History Online,Mainz:Institute of European History,2010; retrieved 14 June 2012.

- Blackwell, Marilyn S."'Women Were Among Our Primeval Abolitionists': Women and Organized Antislavery in Vermont, 1834–1848 ",Vermont History,82 (Winter-Spring 2014), 13–44.

- Carey, Brycchan, and Geoffrey Plank, eds.Quakers and Abolition(University of Illinois Press, 2014), 264 pp.

- Coupland, Sir Reginald. "The British Anti-Slavery Movement". London: F. Cass, 1964.

- Davis, David Brion,The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823(1999);The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture(1988)

- Drescher, Seymour.Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery(2009)

- Finkelman, Paul, ed.Encyclopedia of Slavery(1999)

- Kemner, Jochen."Abolitionism"Archived6 August 2016 at theWayback Machine(2015). University Bielefeld – Center for InterAmerican Studies.

- Gordon, M.Slavery in the Arab World(1989)

- Gould, Philip.Barbaric Traffic: Commerce and Antislavery in the 18th-century Atlantic World(2003)

- Hellie, Richard.Slavery in Russia: 1450–1725(1982)

- Hinks, Peter, and John McKivigan, eds.Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition(2 vol. 2006)ISBN0-313-33142-1;846 pp; 300 articles by experts

- Jeffrey, Julie Roy. "Stranger, Buy... Lest Our Mission Fail: the Complex Culture of Women's Abolitionist Fairs".American Nineteenth Century History4, no. 1 (2003): 185–205.

- Kolchin, Peter.Unfree Labor; American Slavery and Russian Serfdom(1987)

- Kolchin, Peter. "Reexamining Southern Emancipation in Comparative Perspective",Journal of Southern History,(Feb. 2015) 81#1 pp. 7–40.

- Oakes, James.The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution(W.W. Norton, 2021).

- Oakes, James.Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865(W. W. Norton, 2012)

- Palen, Marc-William. "Free-Trade Ideology and Transatlantic Abolitionism: A Historiography".Journal of the History of Economic Thought37 (June 2015): 291–304.

- Reckord, Mary. "The Colonial Office and the Abolition of Slavery."Historical Journal14, no. 4 (1971): 723–734.online

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed.Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World(2007)

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed.The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery(1997)

- Sinha, Manisha.The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition(Yale UP, 2016) 784 pp; Highly detailed coverage of the American movement

- Thomas, Hugh.The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440–1870(2006)

- Unangst, Matthew. "Manufacturing Crisis: Anti-slavery ‘Humanitarianism’ and Imperialism in East Africa, 1888–1890."Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History48.5 (2020): 805–825.

- Wyman‐McCarthy, Matthew. "British abolitionism and global empire in the late 18th century: A historiographic overview."History Compass16.10 (2018): e12480.doi:10.1111/hic3.12480

External links[edit]

- The Abolitionist Seminar,summaries, lesson plans, documents and illustrations for schools; focus on United States

- American Abolitionism,summaries and documents; focus on United States

- Twentieth Century Solutions of the Abolition of Slavery

- Elijah Parish Lovejoy: A Martyr on the Altar of American Liberty

- Brycchan Carey's pages listing British abolitionists

- Teaching resources about Slavery and Abolitionon blackhistory4schools.com

- "The Abolition of the Slave Trade",The National Archives (UK)

- Towards Liberty: Slavery, the Slave Trade, Abolition and Emancipation.Produced by Sheffield City Council's Libraries and Archives (UK)

- The slavery debate

- John Brown Museum

- American Abolitionism

- American Abolitionists,comprehensive list of abolitionists and anti-slavery activists and organizations in the United States

- History of the British abolitionist movementArchived6 April 2007 at theWayback Machineby Right Honourable Lord Archer of Sandwell

- "Slavery – The emancipation movement in Britain",lecture by James Walvin atGresham College,5 March 2007 (available for video and audio download)

- Escape to Freedomat Scholastic.com

- "Black Canada and the Journey to Freedom"

- 1807 Commemorated

- The Action Group

- Trafficking in Persons Report 2008,US Department of State

- National Underground Railroad Freedom Centerin Cincinnati, Ohio