Forty-sevenrōnin

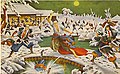

"Revenge of the Loyal Samurai of Akō" by Yasuda Raishū (ja) (Homma Museum of Art), with iconography borrowed from theAdoration of the Shepherds[1] | |

| Native name | Xích tuệ sự kiện |

|---|---|

| English name | Akō incident |

| Date | 31 January 1703 |

| Venue | Kira Residence |

| Coordinates | 35°41′36.0″N139°47′39.5″E/ 35.693333°N 139.794306°E |

| Type | Revenge attack |

| Cause | Death ofAsano Naganori |

| Target | To haveKira Yoshinakacommitritual suicide(seppuku) to avenge their master Asano Naganori's death |

| First reporter | Terasaka Kichiemon |

| Organised by | Forty-sevenrōnin( tứ thập thất sĩ, Akō-rōshi(Xích tuệ lãng sĩ)) led byŌishi Yoshio |

| Participants | 47 |

| Casualties | |

| Forty-sevenrōnin:0 | |

| Kira Yoshinakaand retainers: 41 | |

| Deaths | 19 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 22 |

| Accused | Forty-sevenrōnin |

| Sentence | 46rōninsentenced toritual suicide(seppuku) on 4 February 1703, with 1 pardoned |

The revenge of theforty-sevenrōnin(Tứ thập thất sĩ,Shijūshichishi),[2]also known as theAkō incident(Xích tuệ sự kiện,Akō jiken)orAkō vendetta,is an historical event inJapanin which a band ofrōnin(lordlesssamurai) avenged the death of their master on 31 January 1703.[3]The incident has since become legendary.[4]It is one of the three majoradauchivendetta incidents in Japan, alongside theRevenge of the Soga Brothersand theIgagoe vendetta.[5]

The story tells of a group of samurai after theirdaimyō(feudal lord)Asano Naganoriwas compelled to performseppuku(ritual suicide) for assaulting a powerful court official namedKira Yoshinakaafter the court official insulted him. After waiting and planning for a year, therōninavenged their master's honor by killing Kira. Anticipating the authorities' intolerance of the vendetta's completion, they were prepared to face execution as a consequence. However, due to considerable public support in their favor, the authorities compromised by ordering the rōnin to commitseppukuas an honorable death for the crime ofmurder.This true story was popular in Japanese culture as emblematic of the loyalty, sacrifice, persistence, and honor (qualities samurai follow calledbushidō) that people should display in their daily lives. The popularity of the tale grew during theMeijiera, during which Japan underwent rapid modernisation, and the legend became entrenched within discourses of national heritage and identity.

Fictionalised accounts of the tale of the forty-seven rōnin are known asChūshingura.The story was popularised in numerous plays, including in the genres ofbunrakuandkabuki.Because of thecensorshiplaws of theshogunatein theGenrokuera,which forbade portrayal of current events, the names were changed. While the version given by the playwrights may have come to be accepted as historical fact by some,[who?]the firstChūshingurawas written some 50 years after the event, and numerous historical records about the actual events that predate theChūshingurasurvive.

Thebakufu'scensorshiplaws had relaxed somewhat 75 years after the events in question during the late 18th century when JapanologistIsaac Titsinghfirst recorded the story of the forty-sevenrōninas one of the significant events of theGenrokuera.[6]To this day, the story remains popular in Japan, and each year on 14 December,[3]Sengakuji Temple,where Asano Naganori and therōninare buried, holds a festival commemorating the event.

Name

[edit]The event is known in Japan as theAkō incident(Xích tuệ sự kiện,Akō jiken),sometimes also referred to as theAkō vendetta.The participants in the revenge are called the Akō-rōshi(Xích tuệ lãng sĩ)or Shi-jū-shichi-shi(Tứ thập thất sĩ)in Japanese, and are usually referred to as the "forty-sevenrōnin".Literary accounts of the events are known as theChūshingura(Trung thần tàng,The Treasury of Loyal Retainers).

Story

[edit]For many years, the version of events retold byA. B. MitfordinTales of Old Japan(1871) was generally considered authoritative. The sequence of events and the characters in this narrative were presented to a wide popular readership in theWest.Mitford invited his readers to construe his story of the forty-seven rōnin as historically accurate; and while his version of the tale has long been considered a standard work, some of its details are now questioned.[7]Nevertheless, even with plausible defects, Mitford's work remains a conventional starting point for further study.[7]

Whether as a mere literary device or as a claim for ethnographic veracity, Mitford explains:

In the midst of a nest of venerable trees inTakanawa,a suburb of Yedo, is hidden Sengakuji, or the Spring-hill Temple, renowned throughout the length and breadth of the land for its cemetery, which contains the graves of the forty-seven rônin, famous in Japanese history, heroes of Japanese drama,the tale of whose deed I am about to transcribe.

— Mitford, A. B.[8][emphasis added]

Mitford appended what he explained were translations of Sengaku-ji documents the author had examined personally. These were proffered as "proofs" authenticating the factual basis of his story.[9]These documents were:

- ...the receipt given by the retainers of Kira Kōtsukē no Sukē's son in return for the head of their lord's father, which the priests restored to the family.[10]

- ...a document explanatory of their conduct, a copy of which was found on the person of each of the forty-seven men, dated in the 15th year of Genroku, 12th month.[11]

- ...a paper which the Forty-seven Rōnin laid upon the tomb of their master, together with the head of Kira Kôtsuké no Suké.[12]

Background

[edit]

In 1701, twodaimyō,Asano Takumi-no-Kami Naganori, the youngdaimyōof theAkō Domain(a smallfiefdomin westernHonshū), and Lord Kamei Korechika of theTsuwano Domain,were ordered to arrange a fitting reception for the envoys ofEmperor HigashiyamaatEdo Castle,during theirsankin-kōtaiservice to theshōgun.[13]

Asano and Kamei were to be given instruction in the necessary court etiquette by Kira Kozuke-no-Suke Yoshinaka, a powerful official in the hierarchy ofTokugawa Tsunayoshi's shogunate. He allegedly became upset at them, either because of the insufficient presents they offered him (in the time-honored compensation for such an instructor), or because they would not offer bribes as he wanted. Other sources say that he was naturally rude and arrogant or that he was corrupt, which offended Asano, a devoutlymoralConfucian.By some accounts, it also appears that Asano may have been unfamiliar with the intricacies of the shogunate court and failed to show the proper amount of deference to Kira. Whether Kira treated them poorly, insulted them, or failed to prepare them for fulfilling specificbakufuduties,[14]offence was taken.[6]

Initially, Asano bore all this stoically, while Kamei became enraged and prepared to kill Kira to avenge the insults. However, Kamei's quick-thinking counselors averted disaster for their lord and clan (for all would have been punished if Kamei had killed Kira) by quietly giving Kira a large bribe; Kira thereupon began to treat Kamei nicely, which calmed Kamei.[15]

However, Kira allegedly continued to treat Asano harshly because he was upset that the latter had not emulated his companion. Finally, Kira insulted Asano, calling him a country boor with no manners, and Asano could restrain himself no longer. At theMatsu no Ōrōka,the main grand corridor that interconnects theShiro-shoin( bạch thư viện ) and theŌhiromaof theHonmaru Goten( bổn hoàn ngự điện ) residence, Asano lost his temper and attacked Kira with a dagger, wounding him in the face with his first strike; his second missed and hit a pillar. Guards then quickly separated them.[16]

Kira's wound was hardly serious, but the attack on a shogunate official within the boundaries of theshōgun's residence was considered a grave offence. Any kind of violence, even the drawing of akatana,was completely forbidden in Edo Castle.[17]Thedaimyōof Akō had removed his dagger from its scabbard within Edo Castle, and for that offence, he was ordered to kill himself byseppuku.[6]Asano's goods and lands were to be confiscated after his death, his family was to be ruined, and his retainers were to be maderōnin(leaderless).

This news was carried toŌishi Kuranosuke Yoshio,Asano's principal counsellor, who took command and moved the Asano family away before complying withbakufuorders to surrender the castle to the agents of the government.

Attack

[edit]

After two years, when Ōishi was convinced that Kira was thoroughly off his guard,[18]and everything was ready, he fled from Kyoto, avoiding the spies who were watching him, and the entire band gathered at a secret meeting place in Edo to renew their oaths.

The Ako Incident occurred on 31 January 1703 when therōninof Asano Naganori stormed the residence of Kira Yoshinaka in Edo. (While the attack was carried out on 31 January, the event is commemorated annually on 14 December in Japan.)[3]According to a carefully laid-out plan, they split up into two groups and attacked, armed with swords and bows. One group, led by Ōishi, was to attack the front gate; the other, led by his son, Ōishi Chikara, was to attack the house via the back gate. A drum would sound the simultaneous attack, and a whistle would signal that Kira was dead.[19]

Once Kira was dead, they planned to cut off his head and lay it as an offering on their master's tomb. They would then turn themselves in and wait for their expected sentence of death.[20]All this had been confirmed at a final dinner, at which Ōishi had asked them to be careful and spare women, children, and other helpless people.[21]

Ōishi had four men scale the fence and enter the porter's lodge, capturing and tying up the guard there.[22]He then sent messengers to all the neighboring houses, to explain that they were not robbers but retainers out to avenge the death of their master, and that no harm would come to anyone else: the neighbors were all safe. One of therōninclimbed to the roof and loudly announced to the neighbors that the matter was an act of revenge (katakiuchi,Địch thảo ち). The neighbors, who all hated Kira, were relieved and did nothing to hinder the raiders.[23]

After posting archers (some on the roof) to prevent those in the house (who had not yet awakened) from sending for help, Ōishi sounded the drum to start the attack. Ten of Kira's retainers held off the party attacking the house from the front, but Ōishi Chikara's party broke into the back of the house.[24]

Kira, in terror, took refuge in a closet in the veranda, along with his wife and female servants. The rest of his retainers, who slept in barracks outside, attempted to come into the house to his rescue. After overcoming the defenders at the front of the house, the two parties led by father and son joined up and fought the retainers who came in. The latter, perceiving that they were losing, tried to send for help, but their messengers were killed by the archers posted to prevent that eventuality.[25]

Eventually, after a fierce struggle, the last of Kira's retainers were subdued; in the process, therōninkilled 16 of Kira's men and wounded 22, including his grandson. Of Kira, however, there was no sign. They searched the house, but all they found were crying women and children. They began to despair, but Ōishi checked Kira's bed, and it was still warm, so he knew he could not be far away.[26]

Death of Kira

[edit]A renewed search disclosed an entrance to a secret courtyard hidden behind a large scroll; the courtyard held a small building for storing charcoal and firewood, where two hidden armed retainers were overcome and killed. A search of the building disclosed a man hiding; he attacked the searcher with a dagger, but the man was easily disarmed.[27]He refused to say who he was, but the searchers felt sure it was Kira, and sounded the whistle. Therōningathered, and Ōishi, with a lantern, saw that it was indeed Kira—as a final proof, his head bore the scar from Asano's attack.[28]

Ōishi went on his knees, and in consideration of Kira's high rank, respectfully addressed him, telling him they were retainers of Asano, come to avenge him as true samurai should, and inviting Kira to die as a true samurai should, by killing himself. Ōishi indicated he personally would act as akaishakunin( "second", the one who beheads a person committing seppuku to spare them the indignity of a lingering death) and offered him the same dagger that Asano had used to kill himself.[29]However, no matter how much they entreated him, Kira crouched, speechless and trembling. At last, seeing it was useless to continue asking, Ōishi ordered the otherrōninto pin him down and killed him by cutting off his head with the dagger. They then extinguished all the lamps and fires in the house (lest any cause the house to catch fire and start a general fire that would harm the neighbors) and left, taking Kira's head.[30]

One of therōnin,theashigaruTerasaka Kichiemon, was ordered to travel to Akō and report that their revenge had been completed. (Though Kichiemon's role as a messenger is the most widely accepted version of the story, other accounts have him running away before or after the battle, or being ordered to leave before therōninturned themselves in.)[31]

Aftermath

[edit]

As day was breaking, they quickly carried Kira's head from his residence to their lord's grave in Sengaku-ji temple, marching about ten kilometers across the city, causing a great stir on the way. The story of the revenge spread quickly, and everyone on their path praised them and offered them refreshment.[32]

On arriving at the temple, the remaining 46rōnin(all except Terasaka Kichiemon) washed and cleaned Kira's head in a well, and laid it, and the fateful dagger, before Asano's tomb. They then offered prayers at the temple and gave the abbot of the temple all of the money they had left, asking him to bury them decently and offer prayers for them. They then turned themselves in; the group was broken into four parts and put under guard of four differentdaimyō.[33]During this time, two of Kira's friends came to collect his head for burial; the temple still has the original receipt for the head, which the friends and the priests who dealt with them had all signed.[10]

The shogunate officials in Edo were in a quandary. The samurai had followed the precepts by avenging the death of their lord; but they had also defied the shogunate's authority by exacting revenge, which had been prohibited. In addition, theshōgunreceived a number of petitions from the admiring populace on behalf of therōnin.As expected, therōninwere sentenced to death for the murder of Kira; but theshōgunfinally resolved the quandary by ordering them to honorably commitseppukuinstead of having them executed as criminals.[34]Each of the assailants ended his life in a ritualistic fashion.[6]Ōishi Chikara, the youngest, was only 15 years old on the day the raid took place, and only 16 the day he committedseppuku.

Each of the 46rōninkilled himself inGenroku16, on the 4th day of the 2nd month(Nguyên lộc thập lục niên nhị nguyệt tứ nhật,20 March 1703).[35]This has caused a considerable amount of confusion ever since, with some people referring to the "forty-six rōnin"; this refers to the group put to death by theshōgun,while the actual attack party numbered forty-seven. The forty-seventhrōnin,identified as Terasaka Kichiemon, eventually returned from his mission and was pardoned by theshōgun(some say on account of his youth). He lived until the age of 87, dying around 1747, and was then buried with his comrades. The assailants who died byseppukuwere subsequently interred on the grounds of Sengaku-ji,[6]in front of the tomb of their master.[34]The clothes and arms they wore are still preserved in the temple to this day, along with the drum and whistle; their armor was all home-made, as they had not wanted to arouse suspicion by purchasing any.

The tombs at Sengaku-ji became a place of great veneration, and people flocked there to pray. The graves at the temple have been visited by a great many people throughout the years since the Genroku era.[6]

Members

[edit]

Below are the names of the 47rōninin the following form: family name – pseudonym (kemyō) – real name (imina). Alternative readings are listed in italics.

- Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio/Yoshitaka(Đại thạch nội tàng trợ lương hùng)

- Ōishi Chikara Yoshikane (Đại thạch chủ thuế lương kim)

- Hara Sōemon Mototoki (Nguyên tổng hữu vệ môn nguyên thần)

- Kataoka Gengoemon Takafusa (Phiến cương nguyên ngũ hữu vệ môn cao phòng)

- Horibe Yahei Kanamaru/Akizane(Quật bộ di binh vệ kim hoàn)

- Horibe Yasubei Taketsune(Quật bộ an binh vệ võ dung)

- Yoshida Chūzaemon Kanesuke (Cát điền trung tả vệ môn kiêm lượng)

- Yoshida Sawaemon Kanesada (Cát điền trạch hữu vệ môn kiêm trinh)

- Chikamatsu Kanroku Yukishige (Cận tùng khám lục hành trọng)

- Mase Kyūdayū Masaaki (Gian lại cửu thái phu chính minh)

- Mase Magokurō Masatoki (Gian lại tôn cửu lang chính thần)

- Akabane Genzō Shigekata (Xích thực nguyên tàng trọng hiền)

- Ushioda Matanojō Takanori (Triều điền hựu chi thừa cao giáo)

- Tominomori Sukeemon Masayori (Phú sâm trợ hữu vệ môn chính nhân)

- Fuwa Kazuemon Masatane (Bất phá sổ hữu vệ môn chính chủng)

- Okano Kin'emon Kanehide (Cương dã kim hữu vệ môn bao tú)

- Onodera Jūnai Hidekazu (Tiểu dã tự thập nội tú hòa)

- Onodera Kōemon Hidetomi (Tiểu dã tự hạnh hữu vệ môn tú phú)

- Kimura Okaemon Sadayuki (Mộc thôn cương hữu vệ môn trinh hành)

- Okuda Magodayū Shigemori (Áo điền tôn thái phu trọng thịnh)

- Okuda Sadaemon Yukitaka (Áo điền trinh hữu vệ môn hành cao)

- Hayami Tōzaemon Mitsutaka (Tảo thủy đằng tả vệ môn mãn 尭)

- Yada Gorōemon Suketake (Thỉ điền ngũ lang hữu vệ môn trợ võ)

- Ōishi Sezaemon Nobukiyo (Đại thạch lại tả vệ môn tín thanh)

- Isogai Jūrōzaemon Masahisa (礒 bối thập lang tả vệ môn chính cửu)

- Hazama Kihei Mitsunobu (Gian hỉ binh vệ quang diên)

- Hazama Jūjirō Mitsuoki (Gian thập thứ lang quang hưng)

- Hazama Shinrokurō Mitsukaze (Gian tân lục lang quang phong)

- Nakamura Kansuke Masatoki (Trung thôn khám trợ chính thần)

- Senba Saburobei Mitsutada (Thiên mã tam lang binh vệ quang trung)

- Sugaya Hannojō Masatoshi (Gian cốc bán chi thừa chính lợi)

- Muramatsu Kihei Hidenao (Thôn tùng hỉ binh vệ tú trực)

- Muramatsu Sandayū Takanao (Thôn tùng tam thái phu cao trực)

- Kurahashi Densuke Takeyuki (Thương kiều vân trợ võ hạnh)

- Okajima Yasoemon Tsuneshige (Cương đảo bát thập hữu vệ môn thường thụ)

- Ōtaka Gengo Tadao/Tadatake(Đại cao nguyên ngũ trung hùng)

- Yatō Emoshichi Norikane (Thỉ đầu hữu vệ môn thất giáo kiêm)

- Katsuta Shinzaemon Taketaka (Thắng điền tân tả vệ môn võ 尭)

- Takebayashi Tadashichi Takashige(Võ lâm duy thất long trọng)

- Maebara Isuke Munefusa (Tiền nguyên y trợ tông phòng)

- Kaiga Yazaemon Tomonobu (Bối hạ di tả vệ môn hữu tín)

- Sugino Jūheiji Tsugifusa (Sam dã thập bình thứ thứ phòng)

- Kanzaki Yogorō Noriyasu (Thần kỳ dữ ngũ lang tắc hưu)

- Mimura Jirōzaemon Kanetsune (Tam thôn thứ lang tả vệ môn bao thường)

- Yakokawa Kanbei Munetoshi (Hoành xuyên khám bình tông lợi)

- Kayano Wasuke Tsunenari (Mao dã hòa trợ thường thành)

- Terasaka Kichiemon Nobuyuki (Tự bản cát hữu vệ môn tín hành)

Criticism

[edit]Therōninspent more than 14 months waiting for the "right time" for their revenge. It wasYamamoto Tsunetomo,author of theHagakure,who asked the well known question: "What if, nine months after Asano's death, Kira had died of an illness?" His answer was that the forty-sevenrōninwould have lost their only chance at avenging their master. Even if they had claimed, then, that their dissipated behavior was just an act, that in just a little more time they would have been ready for revenge, who would have believed them? They would have been forever remembered as cowards and drunkards—bringing eternal shame to the name of the Asano clan. The right thing for therōninto do, writes Yamamoto, was to attack Kira and his men immediately after Asano's death. Therōninwould probably have suffered defeat, as Kira was ready for an attack at that time—but this was unimportant.[36]

Ōishi was too obsessed with success, according to Yamamoto. He conceived his convoluted plan to ensure that they would succeed at killing Kira, which is not a proper concern in a samurai: the important thing was not the death of Kira, but for the former samurai of Asano to show outstanding courage and determination in an all-out attack against the Kira house, thus winning everlasting honor for their dead master. Even if they had failed to kill Kira, even if they had all perished, it would not have mattered, as victory and defeat have no importance. By waiting a year, they improved their chances of success but risked dishonoring the name of their clan, the worst sin a samurai can commit.[36]

In the arts

[edit]

The tragedy of the forty-seven rōnin has been one of the most popular themes in Japanese art and has lately even begun to make its way into Western art.

Immediately following the event, there were mixed feelings among the intelligentsia about whether such vengeance had been appropriate. Many agreed that, given their master's last wishes, therōninhad done the right thing, but were undecided about whether such a vengeful wish was proper. Over time, however, the story became a symbol of loyalty to one's master and later, of loyalty to the emperor. Once this happened, the story flourished as a subject of drama, storytelling, and visual art.

Plays

[edit]The incident immediately inspired a succession ofkabukiandbunrakuplays; the first,The Night Attack at Dawn by the Soga,appeared only two weeks after the ronin died. It was shut down by the authorities, but many others soon followed, initially inOsakaandKyoto,farther away from the capital. Some even took the story as far asManila,to spread the story to the rest of Asia.

The most successful of the adaptations was abunrakupuppetplay calledKanadehon Chūshingura(now simply calledChūshingura,or "Treasury of Loyal Retainers" ), written in 1748 by Takeda Izumo and two associates; it was later adapted into akabukiplay, which is still one of Japan's most popular.

In the play, to avoid the attention of the censors, the events are transferred into the distant past, to the 14th century reign ofshōgunAshikaga Takauji.Asano became En'ya Hangan Takasada, Kira becameKō no Moronaoand Ōishi became Ōboshi Yuranosuke Yoshio; the names of the rest of therōninwere disguised to varying degrees. The play contains a number of plot twists that do not reflect the real story: Moronao tries to seduce En'ya's wife, and one of therōnindies before the attack because of a conflict between family and warrior loyalty (another possible cause of the confusion between forty-six and forty-seven).

Opera

[edit]The story was turned into an opera,Chūshingura,byShigeaki Saegusain 1997.[citation needed]

Cinema and television

[edit]The play has been made into a movie at least six times in Japan,[37]the earliest starringOnoe Matsunosuke.The film's release date is questioned, but placed between 1910 and 1917. It has been aired on the Jidaigeki Senmon Channel (Japan) with accompanyingbenshinarration. In 1941, the Japanese military commissioned directorKenji Mizoguchi,who would later directUgetsu,to makeGenroku Chūshingura.They wanted a ferocious morale booster based on the familiarrekishi geki( "historical drama" ) ofThe Loyal 47 Ronin.Instead, Mizoguchi chose for his sourceMayama Chūshingura,a cerebral play dealing with the story. The film was a commercial failure, having been released in Japan one week before theattack on Pearl Harbor.The Japanese military and most audiences found the first part to be too serious, but the studio and Mizoguchi both regarded it as so important that Part Two was put into production, despite lukewarm reception to Part One. The film wasn't shown in America until the 1970s.[38]

The 1958 version,The Loyal 47 Ronin,was directed by Kunio Watanabe.

The 1962 film version directed byHiroshi Inagaki,Chūshingura,is most familiar to Western audiences.[37]In it,Toshirō Mifuneappears in a supporting role as spearman Tawaraboshi Genba. Mifune was to revisit the story several times in his career. In 1971 he appeared in the 52-part television seriesDaichūshinguraas Ōishi, while in 1978 he appeared as Lord Tsuchiya in the epicSwords of Vengeance(Akō-jō danzetsu).

Many Japanese television shows, including single programs, short series, single seasons, and even year-long series such asDaichūshinguraand the more recent NHKTaiga dramaGenroku Ryōran,recount the events. Among both films and television programs, some are quite faithful to theChūshingura,while others incorporate unrelated material or alter details. In addition,gaidendramatize events and characters not in theChūshingura.Kon Ichikawadirectedanother versionin 1994. In 2004,Mitsumasa Saitōdirected a nine-episode mini-series starringKen Matsudaira,who had also starred in a 1999 49-episode TV series of theChūshinguraentitledGenroku Ryōran.InHirokazu Koreeda's 2006 filmHana yori mo nao,the story was used as a backdrop, with one of the ronin being a neighbour of the protagonists.

A comedic adaptation was presented in a 2002 episode of the Canadian television seriesHistory Bitestitled "Samurai Goodfellas", mingling the story with elements fromThe Godfatherfilm series.

Most recently, it was made into a 2013 American movie titled47 Ronin,starringKeanu Reeves,and then again into a more stylized 2015 version titledLast Knights.[39]

Woodblock prints

[edit]The forty-seven rōnin is one of the most popular themes inwoodblock prints,orukiyo-eand many well-known artists have made prints portraying either the original events, scenes from the play, or the actors. One book[which?]on subjects depicted in woodblock prints devotes no fewer than seven chapters to the history of the appearance of this theme in woodblocks. Among the artists who produced prints on this subject areUtamaro,Toyokuni,Hokusai,Kunisada,Hiroshige,andYoshitoshi.[40]However, probably the most widely known woodblocks in the genre are those ofKuniyoshi,who produced at least eleven separate complete series on this subject, along with more than twentytriptychs.

Literature

[edit]- The earliest known account of the Akō incident in the West was published in 1822 inIsaac Titsingh's posthumously-published bookIllustrations of Japan.[6]

- The first book of the juvenile Samurai Mystery series by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler,The Ghost in the Tokaido Inn(2005), weaves the kabuki playThe Forty-Seven Ronininto the plot.

- The incident is the subject ofJorge Luis Borges' short story "The Uncivil Teacher of Court Etiquette Kôtsuké no Suké", included in the 1935 collectionA Universal History of Infamy.

- The legend of the forty-seven rōnin was adapted into two graphic novels published byDark Horse Comics.The first is47 Ronin,a 2014 faithful retelling written byMike Richardsonand illustrated byStan Sakai.[41]The second Dark Horse Comics adaption is Seppuku, the second part ofVíctor Santos' 2017 graphic novelRashomon: A Commissioner Heigo Kobayashi Case,which also adaptsIn a Grove,theRyūnosuke Akutagawashort story the 1950 filmRashomonis based on.[42]

Gallery

[edit]-

Memorial to the unswerving loyalty ofŌishi Yoshioand the others, at the site where they died

-

Incenseburns at the graves of the forty-seven rōnin at Sengaku-ji

-

Entrance to Sengaku Temple

-

Woodcut byKunisadadepicting the attack (early 1800s)

-

Postcard depicting the attack, early 1920s

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^An điền lôi châu bút xích tuệ nghĩa sĩ báo thù đồ[Reward for the Loyal Samurai of Akō by Yasuda Raishū].Homma Museum of Art.25 February 2016.Retrieved18 August2019.

- ^Nghiên cứu xã tân hòa anh đại từ điển[Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary] (in Japanese).Kenkyūsha.

- ^abcDeal, William E. (2007).Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan.Oxford University Press. p. 146.ISBN978-0-19-533126-4.

- ^"Kanadehon".Columbia University.

- ^Ono (2004).Jinbutsudenkojiten Kodai・Chuseihen ( nhân vật vân tiểu từ điển cổ đại ・ trung thế biên ).Japan: Tokyodo Shuppan. p. 186.ISBN4490106467.

- ^abcdefgTitsingh 2006,p. 91.

- ^abAnalysis of Mitford's storybyDr. Henry Smith,Chushinguranew website,Columbia University

- ^(1871).Tales of Old Japan,pp. 5–6.

- ^Mitford, pp. 28–34.

- ^abMitford, p. 30.

- ^Mitford, p. 31.

- ^Mitford, p. 32.

- ^Mitford, A. B. (1871).Tales of Old Japan,p. 7.

- ^Mitford, p. 7.

- ^Mitford, pp. 8–10.

- ^Mitford, pp. 10–11.

- ^Mitford, pp. 11–12.

- ^Mitford, p. 16.

- ^Mitford, pp. 16–17.

- ^Mitford, p. 17

- ^Mitford, pp. 17–18.

- ^Mitford, pp. 18–19.

- ^Mitford, p. 19.

- ^Mitford, pp. 19–20.

- ^Mitford, p. 20.

- ^Mitford, p. 22.

- ^Mitford, p. 23.

- ^Mitford, pp. 23–24.

- ^Mitford, p. 24.

- ^Mitford, pp. 24–25.

- ^Smith, Henry D. II (2004)."The Trouble with Terasaka: The Forty-Seventh Ronin and the Chushingura Imagination"(PDF).Japan Review:16:3–65. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2 November 2013.Retrieved21 January2007.

- ^Mitford, pp. 25–26.

- ^Mitford, pp. 26–27.

- ^abMitford, p. 28.

- ^Tsuchihashi conversionArchived30 September 2007 at theWayback Machine

- ^abYamamoto, T.(Kodansha, 1979).Hagakure,p. 26.

- ^abChild, Ben (9 December 2008)."Keanu Reeves to play Japanese samurai in 47 Ronin".The Guardian.Retrieved15 July2024.

- ^"Movies".Chicago Reader.Archived fromthe originalon 15 May 2008.Retrieved8 May2007.

- ^Stewart, Sara (1 April 2015)."Freeman, Owen casualties of bloody bad 'Last Knights'".

- ^Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2012).Forty-Seven Ronin: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi Edition.Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00ADQGLB8

- ^Richardson, Mike (12 March 2014)."47 Ronin".Dark Horse Comics.

- ^Santos, Víctor (18 October 2017)."Rashomon: A Commissioner Heigo Kobayashi Case".Dark Horse Comics.

Sources

[edit]- Allyn, John. (1981).The Forty-Seven Ronin Story.New York.

- Benesch, Oleg (2014).Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dickens, Frederick V. (1930)Chushingura, or The Loyal League.London.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2012).Forty-Seven Ronin: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi Edition.Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00ADQGLB8

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2012).Forty-Seven Ronin: Utagawa Kuniyoshi Edition.Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00ADQM8II

- Keene, Donald. (1971).Chushingura: A Puppet Play.New York.

- Mitford, Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford, Lord Redesdale (1871).Tales of Old Japan.London: University of Michigan.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Robinson, B.W. (1982).Kuniyoshi: The Warrior Prints.Ithaca.

- Sato, Hiroaki. (1995).Legends of the Samurai.New York.

- Steward, Basil. (1922).Subjects Portrayed in Japanese Colour-Prints.New York.

- Titsingh, Isaac (17 March 2006). Screech, Timon (ed.).Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779–1822.London: Routledge.ISBN978-1-135-78737-0.

- Weinberg, David R. et al. (2001).Kuniyoshi: The Faithful Samurai.Leiden.

Further reading

[edit]- Borges, Jorge Luís (1935).The Uncivil Teacher of Court Etiquette Kôtsuké no Suké;A Universal History of Infamy, Buenos aires 1954, Emecé 1945ISBN0-525-47546-X

- Harper, Thomas (2019).47: The True Story of the Vendetta of the 47 Ronin from Akô.Leete's Island Books.ISBN978-0918172778.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2011).The Revenge of the 47 Ronin,Edo 1703; Osprey Raid Series #23, Osprey Publishing.ISBN978-1-84908-427-7

External links

[edit]- Robson, Lucia St. Clair (1991).The Tokaido Road.Forge Books. New York.

- Chushingura and the Samurai Tradition– Comparisons of the accuracy of accounts by Mitford,Murdochand others, as well as much other useful material, by noted scholars of Japan

- Ako's Forty-Seven Samurai– Web site produced by students at Akō High School; contains the story of the 47 ronin's story, and images of wooden votive tablets of the 47 ronin in the Ōishi Shrine, Akō

- The Trouble with Terasaka: The Forty-Seventh Ronin and the Chushingura Imaginationby Henry D. Smith II,Japan Review,2004, 16:3–65

- Five different woodblock print versions of the story by Ando Hiroshige

- National Diet Library:photograph of Sengaku-ji (1893);photograph of Sengaku-ji (1911)

- Yoshitoshi, 47 Ronin series (1860)

- Discover the tales of Chushingura, the 47 RoninsArchived4 December 2017 at theWayback Machine

- Learn more about the Bushido Way and the Hagakure's criticism of the 47 Ronin.https://think.iafor.org/bushido-way-death/

- Tales of Old Japan by Baron Redesdale(Algernon Mitford)- The first tale is the 47 Ronin.