Amazon rainforest

| Amazon rainforest Portuguese:Floresta amazônica Spanish:Selva amazónica Dutch:Amazoneregenwoud | |

|---|---|

Map of theAmazon rainforest ecoregionsas delineated by theWWFin dark green[1]and theAmazon drainage basinin light green. | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Bolivia,Brazil,Colombia,Ecuador,French Guiana(France),Guyana,Peru,Suriname,andVenezuela |

| Coordinates | 3°S60°W/ 3°S 60°W |

| Area | 5,500,000 km2(2,100,000 sq mi) |

TheAmazon rainforest,[a]also calledAmazon jungleorAmazonia,is amoist broadleaftropical rainforestin theAmazon biomethat covers most of theAmazon basinofSouth America.This basin encompasses 7,000,000 km2(2,700,000 sq mi),[2]of which 6,000,000 km2(2,300,000 sq mi) are covered by therainforest.[3]This region includes territory belonging to nine nations and 3,344 formally acknowledgedindigenous territories.

The majority of the forest, 60%, is inBrazil,followed byPeruwith 13%,Colombiawith 10%, and with minor amounts inBolivia,Ecuador,French Guiana,Guyana,Suriname,andVenezuela.Four nations have "Amazonas"as the name of one of their first-level administrativeregions,andFranceuses the name "Guiana Amazonian Park"for French Guiana's protected rainforest area. The Amazon represents over half ofEarth's remaining rainforests,[4]and comprises the largest and mostbiodiversetract oftropicalrainforest in the world, with an estimated 390 billion individual trees in about 16,000 species.[5]

More than 30 million people of 350 different ethnic groups live in the Amazon, which are subdivided into 9 different national political systems and 3,344 formally acknowledgedindigenous territories.Indigenous peoples make up 9% of the total population, and 60 of the groups remain largely isolated.[6]

Large scaledeforestationis occurring in the forest, creating different harmful effects. Economic losses due to deforestation in Brazil could be approximately 7 times higher in comparison to the cost of all commodities produced through deforestation. In 2023, theWorld Bankpublished a report proposing a non-deforestation based economic program in the region.[7][8]

Etymology

The nameAmazonis said to arise from a warFrancisco de Orellanafought with theTapuyasand other tribes. The women of the tribe fought alongside the men, as was their custom.[9]Orellana derived the nameAmazonasfrom theAmazonsofGreek mythology,described byHerodotusandDiodorus.[9]

History

Based onarchaeologicalevidence from an excavation atCaverna da Pedra Pintada,human inhabitants first settled in the Amazon region at least 11,200 years ago.[11]Subsequent development led to late-prehistoric settlements along the periphery of the forest by AD 1250, which induced alterations in theforest cover.[12]

For a long time, it was thought that the Amazon rainforest was never more than sparsely populated, as it was impossible to sustain a large population throughagriculturegiven the poor soil. ArcheologistBetty Meggerswas a prominent proponent of this idea, as described in her bookAmazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise.She claimed that a population density of 0.2 inhabitants per square kilometre (0.52/sq mi) is the maximum that can be sustained in the rainforest through hunting, with agriculture needed to host a larger population.[13]However, recentanthropologicalfindings have suggested that the region was actually densely populated. TheUpano Valley sitesin present-day eastern Ecuador predate all known complex Amazonian societies.[14]

Some 5 million people may have lived in the Amazon region in AD 1500, divided between dense coastal settlements, such as that atMarajó,and inland dwellers.[15]Based on projections of food production, one estimate suggests over 8 million people living in the Amazon in 1492.[16]By 1900, the native indigenous population had fallen to 1 million and by the early 1980s it was less than 200,000.[15]

The first European to travel the length of theAmazon RiverwasFrancisco de Orellanain 1542.[17]The BBC'sUnnatural Historiespresents evidence that Orellana, rather than exaggerating his claims as previously thought, was correct in his observations that a complex civilization was flourishing along the Amazon in the 1540s. ThePre-Columbian agriculture in the Amazon Basinwas sufficiently advanced to support prosperous and populous societies. It is believed that civilization was later devastated by the spread of diseases from Europe, such assmallpox.[18]This civilization was investigated by the British explorerPercy Fawcettin the early twentieth century. The results of his expeditions were inconclusive, and he disappeared mysteriously on his last trip. His name for this lost civilization was theCity of Z.[citation needed]

Since the 1970s, numerousgeoglyphshave been discovered on deforested land dating between AD 1–1250, furthering claims aboutPre-Columbiancivilizations.[19][20]Ondemar Dias is accredited with first discovering the geoglyphs in 1977, and Alceu Ranzi is credited with furthering their discovery after flying overAcre.[18][21]The BBC'sUnnatural Historiespresented evidence that the Amazon rainforest, rather than being a pristinewilderness,has been shaped by man for at least 11,000 years through practices such asforest gardeningandterra preta.[18]Terra preta is found over large areas in the Amazon forest; and is now widely accepted as a product of indigenoussoil management.The development of this fertile soil allowed agriculture andsilviculturein the previously hostile environment; meaning that large portions of the Amazon rainforest are probably the result of centuries of human management, rather than naturally occurring as has previously been supposed.[22]In the region of theXingutribe, remains of some of these large settlements in the middle of the Amazon forest were found in 2003 by Michael Heckenberger and colleagues of theUniversity of Florida.Among those were evidence of roads, bridges and large plazas.[23]

In the Amazonas, there has been fighting and wars between the neighboring tribes of theJivaro.Several tribes of the Jivaroan group, including theShuar,practisedheadhuntingfor trophies andheadshrinking.[24]The accounts of missionaries to the area in the borderlands between Brazil and Venezuela have recounted constant infighting in theYanomamitribes. More than a third of the Yanomamo males, on average, died from warfare.[25][when?]

TheMundurukuwere awarliketribe that expanded along theTapajósriver and its tributaries and were feared by neighboring tribes. In the early 19th century, the Munduruku were pacified and subjugated by the Brazilians.[26]

During theAmazon rubber boomit is estimated that diseases brought by immigrants, such astyphusandmalaria,killed 40,000 native Amazonians.[27]

In the 1950s, Brazilian explorer and defender of indigenous people,Cândido Rondon,supported theVillas-Bôas brothers' campaign, which faced strong opposition from the government and the ranchers ofMato Grossoand led to the establishment of thefirst Brazilian National Parkfor indigenous people along theXingu Riverin 1961.[28]

In 1961, British explorerRichard Masonwas killed by an uncontacted Amazontribeknown as thePanará.[29]

TheMatsésmade their first permanent contact with the outside world in 1969. Before that date, they were effectively at-war with the Peruvian government.[30]

Geography

Location

Nine countries share the Amazon basin—most of the rainforest, 58.4%, is contained within the borders of Brazil. The other eight countries are Peru with 12.8%, Bolivia with 7.7%, Colombia with 7.1%, Venezuela with 6.1%, Guyana with 3.1%, Suriname with 2.5%, French Guiana with 1.4% and Ecuador with 1%.[31]

Natural

The rainforest likely formed during theEoceneera (from 56 million years to 33.9 million years ago). It appeared following a global reduction of tropical temperatures when theAtlantic Oceanhad widened sufficiently to provide a warm, moist climate to the Amazon basin. The rainforest has been in existence for at least 55 million years, and most of the region remained free ofsavanna-typebiomesat least until thecurrent ice agewhen the climate was drier and savanna more widespread.[32][33]

Following theCretaceous–Paleogene extinction event,the extinction of thedinosaursand the wetter climate may have allowed the tropical rainforest to spread out across the continent. From 66 to 34Mya,the rainforest extended as far south as45°.Climate fluctuations during the last 34 million years have allowed savanna regions to expand into the tropics. During theOligocene,for example, the rainforest spanned a relatively narrow band. It expanded again during theMiddle Miocene,then retracted to a mostly inland formation at thelast glacial maximum.[34]However, the rainforest still managed to thrive during theseglacial periods,allowing for the survival and evolution of a broad diversity of species.[35]

During themid-Eocene,it is believed that thedrainage basinof the Amazon was split along the middle of the continent by thePurus Arch.Water on the eastern side flowed toward the Atlantic, while to the west water flowed toward the Pacific across theAmazonas Basin.As theAndesMountains rose, however, a large basin was created that enclosed a lake; now known as theSolimões Basin.Within the last 5–10 million years, this accumulating water broke through the Purus Arch, joining the easterly flow toward the Atlantic.[36][37]

There is evidence that there have been significant changes in the Amazon rainforestvegetationover the last 21,000 years through thelast glacial maximum(LGM) and subsequent deglaciation. Analyses of sediment deposits from Amazon basin paleolakes and the Amazon Fan indicate that rainfall in the basin during the LGM was lower than for the present, and this was almost certainly associated with reduced moist tropical vegetation cover in the basin.[38]In present day, the Amazon receives approximately 9 feet of rainfall annually. There is a debate, however, over how extensive this reduction was. Some scientists argue that the rainforest was reduced to small, isolatedrefugiaseparated by open forest and grassland;[39]other scientists argue that the rainforest remained largely intact but extended less far to the north, south, and east than is seen today.[40]This debate has proved difficult to resolve because the practical limitations of working in the rainforest mean that data sampling is biased away from the center of the Amazon basin, and both explanations are reasonably well supported by the available data.

Sahara Desert dust windblown to the Amazon

More than 56% of the dust fertilizing the Amazon rainforest comes from theBodélé depressionin Northern Chad in theSaharadesert. The dust containsphosphorus,important for plant growth. The yearly Sahara dust replaces the equivalent amount of phosphorus washed away yearly in Amazon soil from rains and floods.[41]

NASA'sCALIPSOsatellite has measured the amount of dust transported by wind from the Sahara to the Amazon: an average of 182 million tons of dust are windblown out of the Sahara each year, at 15 degrees west longitude, across 2,600 km (1,600 mi) over the Atlantic Ocean (some dust falls into the Atlantic), then at 35 degrees West longitude at the eastern coast of South America, 27.7 million tons (15%) of dust fall over the Amazon basin (22 million tons of it consisting of phosphorus), 132 million tons of dust remain in the air, 43 million tons of dust are windblown and falls on the Caribbean Sea, past 75 degrees west longitude.[42]

CALIPSO uses a laser range finder to scan the Earth's atmosphere for the vertical distribution of dust and other aerosols. CALIPSO regularly tracks the Sahara-Amazon dust plume. CALIPSO has measured variations in the dust amounts transported – an 86 percent drop between the highest amount of dust transported in 2007 and the lowest in 2011.

A possibility causing the variation is theSahel,a strip of semi-arid land on the southern border of the Sahara. When rain amounts in the Sahel are higher, the volume of dust is lower. The higher rainfall could make more vegetation grow in the Sahel, leaving less sand exposed to winds to blow away.[43]

Amazon phosphorus also comes as smoke due to biomass burning in Africa.[44][45]

Biodiversity, flora and fauna

Wet tropical forests are the most species-richbiome,and tropical forests in the Americas are consistently more species rich than the wet forests in Africa and Asia.[46]As the largest tract of tropical rainforest in the Americas, the Amazonian rainforests have unparalleledbiodiversity.One in ten known species in the world lives in the Amazon rainforest.[47]This constitutes the largest collection of livingplantsandanimalspeciesin theworld.[48]

The region is home to about 2.5 million insectspecies,[49]tens of thousands of plants, and some 2,000 birds andmammals.To date, at least 40,000 plant species,[50]2,200fishes,[51]1,294 birds, 427 mammals, 428 amphibians, and 378 reptiles have been scientifically classified in the region.[52]One in five of all bird species are found in the Amazon rainforest, and one in five of the fish species live in Amazonian rivers and streams. Scientists have described between 96,660 and 128,843invertebratespecies inBrazilalone.[53]

The biodiversity of plant species is the highest on Earth with one 2001 study finding a quarter square kilometer (62 acres) of Ecuadorian rainforest supports more than 1,100 tree species.[54]A study in 1999 found one square kilometer (247 acres) of Amazon rainforest can contain about 90,790 tonnes of living plants. The average plant biomass is estimated at 356 ± 47 tonnes per hectare.[55]To date, an estimated 438,000 species of plants of economic and social interest have been registered in the region with many more remaining to be discovered or catalogued.[56]The total number oftreespecies in the region is estimated at 16,000.[5]

The green leaf area of plants and trees in the rainforest varies by about 25% as a result of seasonal changes. Leaves expand during the dry season when sunlight is at a maximum, then undergo abscission in the cloudy wet season. These changes provide a balance of carbon between photosynthesis and respiration.[57]

Each hectare of the Amazon rainforest contains around 1 billion ofinvertebrates.The amount of species per hectare in the Amazon rainforest can be presented in the next table:[58]

| Type of organism | Number of species per hectare |

|---|---|

| Birds | 160 |

| Trees | 310 |

| Epiphytes | 96 |

| Reptile | 22 |

| Amphibians | 33 |

| Fish | 44 |

| Primates | 10 |

The rainforest contains several species that can pose a hazard. Among the largest predatory creatures are theblack caiman,jaguar,cougar,andanaconda.In the river,electric eelscan produce an electric shock that can stun or kill, whilepiranhaare known to bite and injure humans.[59]Various species ofpoison dart frogssecretelipophilicalkaloidtoxins through their flesh. There are also numerous parasites and disease vectors.Vampire batsdwell in the rainforest and can spread therabiesvirus.[60]Malaria,yellow feveranddengue fevercan also be contracted in the Amazon region.

The biodiversity in the Amazon is becoming increasingly threatened, primarily by habitat loss from deforestation as well as increased frequency of fires. Over 90% of Amazonian plant and vertebrate species (13,000–14,000 in total) may have been impacted to some degree by fires.[61]

-

Bullet antshave an extremely painful sting

-

Parrots at clay lick inYasuni National Park,Ecuador

-

Pipa pipa,a species of frog found within the Amazon.

-

Scarlet macaw,indigenous to the American tropics.

-

Titan Beetleis most generally associated with the Amazon Rainforest, it may also be found in other parts of South America if ecological conditions are favorable

Deforestation

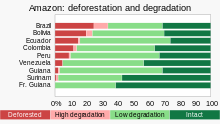

Deforestationis the conversion of forested areas to non-forested areas. The main sources of deforestation in the Amazon are human settlement and the development of the land.[64]In 2022, about 20% of the Amazon rainforest has already been deforested and a further 6% was "highly degraded".[65]Research suggests that upon reaching about 20–25% (hence 0–5% more), thetipping pointto flip it into a non-forest ecosystem – degradedsavannah– (in eastern, southern and central Amazonia) will be reached.[66][67][68]This process of savanisation would take decades to take full effect.[65]

Prior to the early 1960s, access to the forest's interior was highly restricted, and the forest remained basically intact.[69]Farms established during the 1960s were based on crop cultivation and theslash and burnmethod. However, the colonists were unable to manage their fields and the crops because of the loss ofsoil fertilityand weed invasion.[70]The soils in the Amazon are productive for just a short period of time, so farmers are constantly moving to new areas and clearing more land.[70]These farming practices led to deforestation and caused extensive environmental damage.[71]Deforestation is considerable, and areas cleared of forest are visible to the naked eye from outer space.

In the 1970s, construction began on theTrans-Amazonian highway.This highway represented a major threat to the Amazon rainforest.[72]The highway still has not been completed, limiting the environmental damage.

Between 1991 and 2000, the total area of forest lost in the Amazon rose from 415,000 to 587,000 km2(160,000 to 227,000 sq mi), with most of the lost forest becoming pasture for cattle.[73]Seventy percent of formerly forested land in the Amazon, and 91% of land deforested since 1970, have been used for livestockpasture.[74][75]Currently, Brazil is the largest global producer ofsoybeans.New research however, conducted by Leydimere Oliveira et al., has shown that the more rainforest is logged in the Amazon, the less precipitation reaches the area and so the lower the yield per hectare becomes. So despite the popular perception, there has been no economical advantage for Brazil from logging rainforest zones and converting these to pastoral fields.[76]

The needs of soy farmers have been used to justify many of the controversial transportation projects that are currently developing in the Amazon. The first two highways successfully opened up the rainforest and led to increased settlement and deforestation. The mean annual deforestation rate from 2000 to 2005 (22,392 km2or 8,646 sq mi per year) was 18% higher than in the previous five years (19,018 km2or 7,343 sq mi per year).[77]Although deforestation declined significantly in the Brazilian Amazon between 2004 and 2014, there has been an increase to the present day.[78]

Brazil's President, Jair Bolsonaro, has supported the relaxation of regulations placed on agricultural land. He has used his time in office to allow for more deforestation and more exploitation of the Amazon's rich natural resources.

Since the discovery offossil fuelreservoirs in the Amazon rainforest, oil drilling activity has steadily increased, peaking in the Western Amazon in the 1970s and ushering another drilling boom in the 2000s.[79]Oil companies have to set up their operations by opening new roads through the forests, which often contributes to deforestation in the region.[80]

TheEuropean Union–Mercosur free trade agreement,which would form one of the world's largest free trade areas, has been denounced by environmental activists and indigenous rights campaigners.[81]The fear is that the deal could lead to more deforestation of the Amazon rainforest as it expands market access to Brazilian beef.[82]

According to a November 2021 report by Brazil'sINPE,based onsatellite data,deforestation has increased by 22% over 2020 and is at its highest level since 2006.[83][84]

2019 fires

There were 72,843 fires in Brazil in 2019, with more than half within the Amazon region.[85][86][87]In August 2019 there were a record number of fires.[88]Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazonrose more than 88% in June 2019 compared with the same month in 2018.[89]

-

NASA satellite observation of deforestation in the Mato Grosso state of Brazil. The transformation from forest to farm is evident by the paler square shaped areas under development.

-

Fires and deforestation in the state ofRondônia

-

One consequence of forest clearing in the Amazon: thick smoke that hangs over the forest

-

Impact of deforestation on natural habitat of trees

The increased area of fire-impacted forest coincided with a relaxation of environmental regulations from the Brazilian government. Notably, before those regulations were put in place in 2008 the fire-impacted area was also larger compared to the regulation period of 2009–2018. As these fire continue to move closer to the heart of the Amazon basin, their impact on biodiversity will only increase in scale, as the cumulative fire-impacted area is correlated with the number of species impacted.[61]

Conservation and climate change

Environmentalists are concerned aboutloss of biodiversitythat will result fromdestruction of the forest,and also about therelease of the carboncontained within the vegetation, which could accelerateglobal warming.Amazonian evergreen forests account for about 10% of the world's terrestrial primary productivity and 10% of thecarbon storesin ecosystems[90]– of the order of 1.1 × 1011metric tonnes of carbon.[91]Amazonian forests are estimated to have accumulated 0.62 ± 0.37 tons of carbon per hectare per year between 1975 and 1996.[91]In 2021 it was reported that the Amazon for the first time emitted more greenhouse gases than it absorbed.[92]Though often referenced as producing more than a quarter of the Earth's oxygen, this often stated, but misused statistic actually refers to oxygen turnover. The net contribution of the ecosystem is approximately zero.[93]

Onecomputer modelof futureclimate changecaused bygreenhouse gas emissionsshows that the Amazon rainforest could become unsustainable under conditions of severely reduced rainfall and increased temperatures, leading to an almost complete loss of rainforest cover in the basin by 2100.,[94][95]and severe economic,natural capitalandecosystem servicesimpacts of not averting the tipping point.[96]However, simulations of Amazon basin climate change across many different models are not consistent in their estimation of any rainfall response, ranging from weak increases to strong decreases.[97]The result indicates that the rainforest could be threatened through the 21st century by climate change in addition to deforestation.

In 1989, environmentalist C.M. Peters and two colleagues stated there is economic as well as biological incentive to protecting the rainforest. One hectare in thePeruvian Amazonhas been calculated to have a value of $6820 ifintact forestis sustainably harvested for fruits, latex, and timber; $1000 if clear-cut for commercial timber (not sustainably harvested); or $148 if used as cattle pasture.[98]

As indigenous territories continue to be destroyed by deforestation andecocide(such as in thePeruvian Amazon),[99]indigenous peoples' rainforest communities continue to disappear, while others, like theUrarinacontinue to struggle to fight for their cultural survival and the fate of their forested territories. Meanwhile, the relationship between non-human primates in the subsistence and symbolism of indigenous lowland South American peoples has gained increased attention, as have ethno-biology andcommunity-based conservationefforts.

From 2002 to 2006, the conserved land in the Amazon rainforest almost tripled and deforestation rates dropped up to 60%. About 1,000,000 km2(250,000,000 acres) have been put onto some sort of conservation, which adds up to a current amount of 1,730,000 km2(430,000,000 acres).[100]

In April 2019, theEcuadoriancourt stopped oil exploration activities in 180,000 hectares (440,000 acres) of the Amazon rainforest.[101]

In July 2019, the Ecuadorian court forbade the government to sell territory with forests to oil companies.[102]

In September 2019, the US and Brazil agreed to promote private-sector development in the Amazon. They also pledged a $100m biodiversity conservation fund for the Amazon led by the private sector. Brazil's foreign minister stated that opening the rainforest to economic development was the only way to protect it.[103]

-

Anthropogenic emission of greenhouse gases broken down by sector for the year 2000.

-

Aerosols over the Amazon each September for four burning seasons (2005 through 2008). Theaerosolscale (yellow to dark reddish-brown) indicates the relative amount of particles that absorb sunlight.

-

Aerial roots of red mangrove on an Amazonian river.

-

Climate change disturbances of rainforests.[104]

A 2009 study found that a 4 °C rise (above pre-industrial levels) in global temperatures by 2100 would kill 85% of the Amazon rainforest while a temperature rise of 3 °C would kill some 75% of the Amazon.[105]

A new study by an international team of environmental scientists in the Brazilian Amazon shows that protection of freshwater biodiversity can be increased by up to 600% through integrated freshwater-terrestrial planning .[106]

Deforestationin the Amazon rainforest region has a negative impact on local climate.[107]It was one of the main causes of the severedroughtof 2014–2015 in Brazil.[108][109]This is because the moisture from the forests is important to the rainfall inBrazil,ParaguayandArgentina.Half of the rainfall in the Amazon area is produced by the forests.[110]

Results of a 2021scientific synthesisindicate that, in terms of global warming, theAmazon basinwith the Amazon rainforest is currently emitting moregreenhouse gasesthanit absorbsoverall. Climate change impacts and human activities in the area – mainly wildfires, current land-use anddeforestation– are causing a release of forcing agents that likely result in a net warming effect.[111][104][112]

In 2022 the supreme court of Ecuador decided that "" under no circumstances can a project be carried out that generates excessive sacrifices to the collective rights of communities and nature. "It also required the government to respect the opinion ofIndigenous peoples of the Americasabout different industrial projects on their land. Advocates of the decision argue that it will have consequences far beyond Ecuador. In general, ecosystems are in better shape whenindigenous peoplesown or manage the land.[113]

Due to the conservation policies ofLuiz Inácio Lula da Silvain the first 10 months of 2023 deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon decreased by around 50% compared to the same period in 2022. This was despite a severe drought, one of the worst on record, that exacerbated the situation. Climate change, El Nino, deforestation increases the likelihood of drought condition in the Amazon.[114]

According to Amazon Conservation's MAAP forest monitoring program, the deforestation rate in the Amazon from the January 1 to November 8, 2023, decreased by 56% in comparison to the same period in 2022. The main cause is the decline in deforestation rate in Brazil, due to the government's policies, while Columbia, Peru and Bolivia also reduced deforestation.[115]

In January 2024 published data showed a 50% decline in deforestation rate in the Amazon rainforest and 43% rise in vegetation loss in the neighborCerradoduring the year of 2023 in comparison to 2022. Both biomes together lose 12,980 km², 18% less than in 2022.[116]

Remote sensing

The use ofremotely senseddata is dramatically improving conservationists' knowledge of the Amazon basin. Given the objectivity and lowered costs ofsatellite-basedland cover and -change analysis, it appears likely that remote sensing technology will be an integral part of assessing the extents, locations and damage of deforestation in the basin.[117]Furthermore, remote sensing is the best and perhaps only possible way to study the Amazon on a large scale.[118]

The use of remote sensing for the conservation of the Amazon is also being used by the indigenous tribes of the basin to protect their tribal lands from commercial interests. Using handheldGPSdevices and programs likeGoogle Earth,members of the Trio Tribe, who live in the rainforests of southern Suriname, map out their ancestral lands to help strengthen their territorial claims.[119]Currently, most tribes in the Amazon do not have clearly defined boundaries, making it easier for commercial ventures to target their territories.

To accurately map the Amazon's biomass and subsequent carbon-related emissions, the classification of tree growth stages within different parts of the forest is crucial. In 2006, Tatiana Kuplich organized the trees of the Amazon into four categories: mature forest, regenerating forest [less than three years], regenerating forest [between three and five years of regrowth], and regenerating forest [eleven to eighteen years of continued development].[120]The researcher used a combination ofsynthetic aperture radar(SAR) andThematic Mapper(TM) to accurately place the different portions of the Amazon into one of the four classifications.

Impact of early 21st-century Amazon droughts

In 2005, parts of the Amazon basin experienced the worst drought in one hundred years,[121]and there were indications that 2006 may have been a second successive year of drought.[122]A 2006 article in the UK newspaperThe Independentreported theWoods Hole Research Centerresults, showing that the forest in its present form could survive only three years of drought.[123][124]Scientists at the BrazilianNational Institute of Amazonian Researchargued in the article that this drought response, coupled with the effects of deforestation on regional climate, are pushing the rainforest towards a "tipping point"where it would irreversibly start to die.[125]It concluded that the forest is on the brink of[vague]being turned intosavannaor desert, with catastrophic consequences for the world's climate.[citation needed]A study published inNature Communicationsin October 2020 found that about 40% of the Amazon rainforest is at risk of becoming a savanna-like ecosystem due to reduced rainfall.[126]A study published inNature climate changeprovided direct empirical evidence that more than three-quarters of the Amazon rainforest has been losing resilience since the early 2000s, risking dieback with profound implications for biodiversity, carbon storage and climate change at a global scale.[127]

According to theWorld Wide Fund for Nature,the combination of climate change and deforestation increases the drying effect of dead trees that fuelsforest fires.[128]

In 2010, the Amazon rainforest experienced another severe drought, in some ways more extreme than the 2005 drought. The affected region was approximately 3,000,000 km2(1,160,000 sq mi) of rainforest, compared with 1,900,000 km2(734,000 sq mi) in 2005. The 2010 drought had three epicenters where vegetation died off, whereas in 2005, the drought was focused on the southwestern part. The findings were published in the journalScience.In a typical year, the Amazon absorbs 1.5 gigatons of carbon dioxide; during 2005 instead 5 gigatons were released and in 2010 8 gigatons were released.[129][130]Additional severe droughts occurred in 2010, 2015, and 2016.[131]

In 2019 Brazil's protections of the Amazon rainforest were slashed, resulting in a severe loss of trees.[132]According to Brazil'sNational Institute for Space Research(INPE), deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon rose more than 50% in the first three months of 2020 compared to the same three-month period in 2019.[133]

In 2020, a 17 percent rise was noted in theAmazon wildfires,marking the worst start to the fire season in a decade. The first 10 days of August 2020 witnessed 10,136 fires. An analysis of the government figures reflected 81 per cent increase in fires in federal reserves, in comparison with the same period in 2019.[134]However, PresidentJair Bolsonaroturned down the existence of fires, calling it a "lie", despite the data produced by his own government.[135]Satellites in September recorded 32,017 hotspots in the world's largest rainforest, a 61% rise from the same month in 2019.[136]In addition, October saw a huge surge in the number of hotspots in the forest (more than 17,000 fires are burning in the Amazon's rainforest) – with more than double the amount detected in the same month last year.[137]

Possibility of forest-friendly economy

In 2023 theWorld Bank,published a report named: "A Balancing Act for Brazil's Amazonian States: An Economic Memorandum". The report stating that economic losses due to deforestation in Brazil could reach around 317 billion dollars per year, approximately 7 times higher in comparison to the cost of all commodities produced through deforestation, proposed non-deforestation based economic program in the region of the Amazon rainforest.[7][8]

Silvopasture(integrating trees, forage and grazing) can help to stop deforestation in the region.[138]

According to WWF,ecotourismcould help the Amazon to reduce deforestation and climate change. Ecotourism is currently still little practiced in the Amazon, partly due to lack of information about places where implementation is possible. Ecotourism is a sector that can also be taken up by the Indigenous community in the Amazon as a source of income and revenue. An ecotourism project in the Brazilian section of the rainforest had been under consideration by Brazil's State Secretary for the Environment and Sustainable Development in 2009, along theAripuanã River,in the Aripuanã Sustainable Development Reserve.[139]Also, some community-based ecotourism exists in theMamirauá Sustainable Development Reserve.[140]Ecotourism is also practiced in the Peruvian section of the rainforest.A few ecolodges are for instance present between Cusco and Madre de Dios.[141]

In May 2023 Brazil's bank federation decided to implement a new sustainability standard demanding from meatpackers to ensure their meat is not coming from illegally deforested area. Credits will not be given to those who will not meet the new standards. The decision came after the European Union decides to implement regulations to stop deforestation. Brazil beef exporters, said the standard is not just because it is not applied to land owners.[142]21 banks representing 81% of the credit market in Brazil agree to follow those rules.[143]

According to a statement of the Colombian government deforestation rates inthe Colombian Amazonfell by 70% in the first 9 months of 2023 compared to the same period in the previous year, what can be attributed to the conservation policies of the government. One of them is paying local residents for conserving the forest.[144]

See also

- Organizations

- Technology

- Amazon Surveillance System(Sistema de Vigilância da Amazônia)

- Global Forest Watch

Notes

- ^Portuguese:Floresta amazônicaorAmazônia;Spanish:Selva amazónica,Amazonía,or usuallyAmazonia;French:Forêt amazonienne;Dutch:Amazoneregenwoud.In English, the names are sometimes capitalized further, as Amazon Rainforest, Amazon Forest, or Amazon Jungle.

- ^Many arecaboclosormestiço(mixed-race), also calledpardos,descendants of Amazonian indigenous people and white Portuguese colonizers. Despite their indigenous ancestry, they no longer identify with any indigenous ethnicity.

References

- ^"WWF – About the Amazon".Archivedfrom the original on October 7, 2019.RetrievedOctober 11,2019.

- ^"Amazon River".britannica.com.Encyclopaedia Britannica. January 11, 2024.

- ^"Amazon Rainforest".britannica.com.Encyclopaedia Britannica. May 30, 2024.

- ^"WNF: Places: Amazon".Archivedfrom the original on April 13, 2020.RetrievedJune 4,2016.

- ^ab"Field Museum scientists estimate 16,000 tree species in the Amazon".Field Museum.October 17, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on December 7, 2019.RetrievedOctober 18,2013.

- ^"Inside the Amazon".Archivedfrom the original on October 7, 2019.RetrievedNovember 5,2020.

- ^ab"World Bank: Brazil faces $317 billion in annual losses to Amazon deforestation".8.9ha.World Bank. May 24, 2023.RetrievedMay 30,2023.

- ^ab"A Balancing Act for Brazil's Amazonian States: An Economic Memorandum." Executive Summary booklet.The World Bank. 2023.RetrievedMay 30,2023.

- ^abTaylor, Isaac (1898).Names and Their Histories: A Handbook of Historical Geography and Topographical Nomenclature.London: Rivingtons.ISBN978-0-559-29668-0.Archivedfrom the original on July 25, 2020.RetrievedOctober 12,2008.

- ^"Yanomami".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on July 25, 2020.RetrievedJune 20,2020.

- ^Roosevelt, A.C.; da Costa, M. Lima; Machado, C. Lopes; Michab, M.; Mercier, N.; Valladas, H.; Feathers, J.; Barnett, W.; da Silveira, M. Imazio; Henderson, A.; Sliva, J.; Chernoff, B.; Reese, D.S.; Holman, J.A.; Toth, N.; Schick, K. (April 19, 1996). "Paleoindian Cave Dwellers in the Amazon: The Peopling of the Americas".Science.272(5260): 373–384.Bibcode:1996Sci...272..373R.doi:10.1126/science.272.5260.373.S2CID129231783.

- ^Heckenberger, Michael J.; Kuikuro, Afukaka; Kuikuro, Urissapá Tabata; Russell, J. Christian; Schmidt, Morgan; Fausto, Carlos; Franchetto, Bruna (September 19, 2003). "Amazonia 1492: Pristine Forest or Cultural Parkland?".Science.301(5640): 1710–1714.Bibcode:2003Sci...301.1710H.doi:10.1126/science.1086112.PMID14500979.S2CID7962308.

- ^Meggers, Betty J. (December 19, 2003). "Revisiting Amazonia Circa 1492".Science.302(5653): 2067–2070.doi:10.1126/science.302.5653.2067b.PMID14684803.S2CID5316715.

- ^"Remnants of Sprawling Ancient Cities Are Found in the Amazon".The New York Times.January 23, 2024.RetrievedJanuary 30,2024.

- ^abChris C. Park (2003).Tropical Rainforests.Routledge. p. 108.ISBN978-0-415-06239-8.Archivedfrom the original on January 10, 2022.RetrievedAugust 24,2017.

- ^Clement, Charles R.; Denevan, William M.; Heckenberger, Michael J.; Junqueira, André Braga; Neves, Eduardo G.; Teixeira, Wenceslau G.; Woods, William I. (August 7, 2015)."The domestication of Amazonia before European conquest".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.282(1812): 20150813.doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0813.ISSN0962-8452.PMC4528512.PMID26202998.

- ^Smith, A (1994).Explorers of the Amazon.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0-226-76337-8.

- ^abc"Unnatural Histories – Amazon".BBC Four.Archivedfrom the original on January 8, 2020.RetrievedMay 9,2012.

- ^Simon Romero (January 14, 2012)."Once Hidden by Forest, Carvings in Land Attest to Amazon's Lost World".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on December 26, 2019.RetrievedFebruary 26,2017.

- ^Martti Pärssinen; Denise Schaan; Alceu Ranzi (2009). "Pre-Columbian geometric earthworks in the upper Purús: a complex society in western Amazonia".Antiquity.83(322): 1084–1095.doi:10.1017/s0003598x00099373.S2CID55741813.

- ^Junior, Gonçalo (October 2008)."Amazonia lost and found".Pesquisa (Ed.220).Archived fromthe originalon August 12, 2014.

- ^The influence of human alteration has been generally underestimated, reports Darna L. Dufour: "Much of what has been considered natural forest in Amazonia is probably the result of hundreds of years of human use and management." "Use of Tropical Rainforests by Native Amazonians,"BioScience40, no. 9 (October 1990):658. For an example of how such peoples integrated planting into their nomadic lifestyles, seeRival, Laura (1993). "The Growth of Family Trees: Understanding Huaorani Perceptions of the Forest".Man.28(4): 635–652.doi:10.2307/2803990.JSTOR2803990.

- ^Heckenberger, M.J.; Kuikuro, A; Kuikuro, UT; Russell, JC; Schmidt, M; Fausto, C; Franchetto, B (September 19, 2003), "Amazonia 1492: Pristine Forest or Cultural Parkland?",Science,vol. 301, no. 5640 (published 2003), pp. 1710–14,Bibcode:2003Sci...301.1710H,doi:10.1126/science.1086112,PMID14500979,S2CID7962308

- ^"The Amazon's head hunters and body shrinkers".The Week.January 20, 2012.Archivedfrom the original on October 13, 2018.RetrievedSeptember 12,2019.

- ^Chagnon, Napoleon A. (1992).Yanomamo.New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- ^"Mundurukú people".britannica.com.Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^La Republica Oligarchic. Editorial Lexus 2000 p. 925.

- ^From the first expedition to the creation of the Park,pib.socioambiental.org

- ^"Rain delays rescue of explorers".The Herald.Glasgow,Scotland.September 8, 1961. p. 8 – via Google News.

- ^Snell, Ron (February 2, 2006).Jungle Calls(Kindle ed.). Garland, Texas: Hannibal Books.ISBN0-929292-86-3.RetrievedMay 27,2020.

- ^Coca-Castro, Alejandro; Reymondin, Louis; Bellfield, Helen; Hyman, Glenn (January 2013),Land use Status and Trends in Amazonia(PDF),Amazonia Security Agenda Project, archived fromthe original(PDF)on March 19, 2016,retrievedAugust 25,2019

- ^Morley, Robert J. (2000).Origin and Evolution of Tropical Rain Forests.Wiley.ISBN978-0-471-98326-2.

- ^Burnham, Robyn J.; Johnson, Kirk R. (2004)."South American palaeobotany and the origins of neotropical rainforests".Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.359(1450): 1595–1610.doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1531.PMC1693437.PMID15519975.

- ^Maslin, Mark; Malhi, Yadvinder; Phillips, Oliver; Cowling, Sharon (2005)."New views on an old forest: assessing the longevity, resilience and future of the Amazon rainforest"(PDF).Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers.30(4): 477–499.Bibcode:2005TrIBG..30..477M.doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2005.00181.x.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on October 1, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 25,2008.

- ^Malhi, Yadvinder; Phillips, Oliver (2005).Tropical Forests & Global Atmospheric Change.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-856706-6.

- ^Costa, João Batista Sena; Bemerguy, Ruth Léa; Hasui, Yociteru; Borges, Maurício da Silva (2001). "Tectonics and paleogeography along the Amazon river".Journal of South American Earth Sciences.14(4): 335–347.Bibcode:2001JSAES..14..335C.doi:10.1016/S0895-9811(01)00025-6.

- ^Milani, Edison José; Zalán, Pedro Victor (1999)."An outline of the geology and petroleum systems of the Paleozoic interior basins of South America".Episodes.22(3): 199–205.doi:10.18814/epiiugs/1999/v22i3/007.

- ^Colinvaux, Paul A.; Oliveira, Paulo E. De (2000). "Palaeoecology and climate of the Amazon basin during the last glacial cycle".Journal of Quaternary Science.15(4): 347–356.Bibcode:2000JQS....15..347C.doi:10.1002/1099-1417(200005)15:4<347::AID-JQS537>3.0.CO;2-A.

- ^Van Der Hammen, Thomas; Hooghiemstra, Henry (2000). "Neogene and Quaternary history of vegetation, climate, and plant diversity in Amazonia".Quaternary Science Reviews.19(8): 725.Bibcode:2000QSRv...19..725V.CiteSeerX10.1.1.536.519.doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00024-4.

- ^Colinvaux, P.A.; De Oliveira, P.E.; Bush, M.B. (January 2000). "Amazonian and neotropical plant communities on glacial time-scales: The failure of the aridity and refuge hypotheses".Quaternary Science Reviews.19(1–5): 141–169.Bibcode:2000QSRv...19..141C.doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00059-1.

- ^Yu, Hongbin (2015)."The fertilizing role of African dust in the Amazon rainforest: A first multiyear assessment based on data from Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observations".Geophysical Research Letters.42(6): 1984–1991.Bibcode:2015GeoRL..42.1984Y.doi:10.1002/2015GL063040.

- ^Garner, Rob (February 24, 2015)."Saharan Dust Feeds Amazon's Plants".NASA.Archivedfrom the original on June 23, 2019.RetrievedJune 20,2019.

- ^"Desert Dust Feeds Amazon Forests – NASA Science".nasa.gov.Archivedfrom the original on May 14, 2017.RetrievedJuly 12,2017.

- ^Barkley, Anne E.; Prospero, Joseph M.;Mahowald, Natalie;Hamilton, Douglas S.; Popendorf, Kimberly J.; Oehlert, Amanda M.; Pourmand, Ali; Gatineau, Alexandre; Panechou-Pulcherie, Kathy; Blackwelder, Patricia; Gaston, Cassandra J. (August 13, 2019)."African biomass burning is a substantial source of phosphorus deposition to the Amazon, Tropical Atlantic Ocean, and Southern Ocean".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.116(33): 16216–16221.Bibcode:2019PNAS..11616216B.doi:10.1073/pnas.1906091116.PMC6697889.PMID31358622.

- ^"Smoke from Africa fertilizes the Amazon and tropical ocean regions with soluble phosphorous".phys.org.Archivedfrom the original on August 14, 2019.RetrievedAugust 14,2019.

- ^Turner, I.M. (2001).The ecology of trees in the tropical rain forest.Cambridge University Press,Cambridge.ISBN0-521-80183-4[page needed]

- ^"Amazon Rainforest, Amazon Plants, Amazon River Animals".World Wide Fund for Nature.Archivedfrom the original on May 17, 2008.RetrievedMay 6,2008.

- ^Weisberger, Mindy (March 26, 2024)."Ancient giant dolphin discovered in the Amazon".CNN.RetrievedMarch 29,2024.

- ^"Photos / Pictures of the Amazon Rainforest".Travel.mongabay.com.Archivedfrom the original on December 17, 2008.RetrievedDecember 18,2008.

- ^"Rainforest".National Geographic.

- ^James S. Albert; Roberto E. Reis (March 8, 2011).Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes.University of California Press. p. 308.Archivedfrom the original on June 30, 2011.RetrievedJune 28,2011.

- ^Da Silva; Jose Maria Cardoso; et al. (2005). "The Fate of the Amazonian Areas of Endemism".Conservation Biology.19(3): 689–694.Bibcode:2005ConBi..19..689D.doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00705.x.S2CID85843442.

- ^Lewinsohn, Thomas M.; Paulo Inácio Prado (June 2005). "How Many Species Are There in Brazil?".Conservation Biology.19(3): 619–624.Bibcode:2005ConBi..19..619L.doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00680.x.S2CID84691981.

- ^Wright, S. Joseph (October 12, 2001). "Plant diversity in tropical forests: a review of mechanisms of species coexistence".Oecologia.130(1): 1–14.Bibcode:2002Oecol.130....1W.doi:10.1007/s004420100809.PMID28547014.S2CID4863115.

- ^Laurance, William F.; Fearnside, Philip M.; Laurance, Susan G.; Delamonica, Patricia; Lovejoy, Thomas E.; Rankin-de Merona, Judy M.; Chambers, Jeffrey Q.; Gascon, Claude (June 14, 1999). "Relationship between soils and Amazon forest biomass: a landscape-scale study".Forest Ecology and Management.118(1–3): 127–138.doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(98)00494-0.

- ^"Amazon Rainforest".South AmericaTravel Guide. Archived fromthe originalon August 12, 2008.RetrievedAugust 19,2008.

- ^Mynenia, Ranga B.; et al. (March 13, 2007)."Large seasonal swings in leaf area of Amazon rainforests".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.104(12): 4820–4823.Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.4820M.doi:10.1073/pnas.0611338104.PMC1820882.PMID17360360.

- ^Costa, Camilla (May 21, 2020)."Amazon under threat: Fires, loggers and now virus".BBC.RetrievedNovember 14,2023.

- ^"Piranha 'less deadly than feared'".BBC News.July 2, 2007.Archivedfrom the original on July 7, 2007.RetrievedJuly 2,2007.

- ^da Rosa; Elizabeth S. T.; et al. (August 2006)."Bat-transmitted Human Rabies Outbreaks, Brazilian Amazon".Emerging Infectious Diseases.12(8): 1197–1202.doi:10.3201/eid1708.050929.PMC3291204.PMID16965697.

- ^abFeng, Xiao; Merow, Cory; Liu, Zhihua; Park, Daniel S.; Roehrdanz, Patrick R.; Maitner, Brian; Newman, Erica A.; Boyle, Brad L.; Lien, Aaron; Burger, Joseph R.; Pires, Mathias M. (September 1, 2021)."How deregulation, drought and increasing fire impact Amazonian biodiversity".Nature.597(7877): 516–521.Bibcode:2021Natur.597..516F.doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03876-7.ISSN1476-4687.PMID34471291.S2CID237388791.Archivedfrom the original on September 12, 2021.RetrievedSeptember 11,2021.

- ^"Forest Pulse: The Latest on the World's Forests".WRI.org.World Resources Institute. April 28, 2022.Archivedfrom the original on April 28, 2022.● 2022 Global Forest Watch data quoted byMcGrath, Matt; Poynting, Mark (June 27, 2023)."Climate change: Deforestation surges despite pledges".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on June 29, 2023.

- ^"Amazon Against the Clock: A Regional Assessment on Where and How to Protect 80% by 2025"(PDF).Amazon Watch.September 2022. p. 8.Archived(PDF)from the original on September 10, 2022.

Graphic 2: Current State of the Amazon by country, by percentage / Source: RAISG (Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada) Elaborated by authors.

- ^Various (2001). Bierregaard, Richard; Gascon, Claude; Lovejoy, Thomas E.; Mesquita, Rita (eds.).Lessons from Amazonia: The Ecology and Conservation of a Fragmented Forest.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-08483-2.

- ^abTandon, Ayesha (October 4, 2023)."Drying of Amazon could be early warning of 'tipping point' for the rainforest".Carbon Brief.RetrievedOctober 6,2023.

- ^"Amazon Rainforest 'heading to point of no return'".February 22, 2018.Archivedfrom the original on September 22, 2020.RetrievedJuly 6,2019.

- ^Lovejoy, Thomas E.; Nobre, Carlos (2018)."Amazon Tipping Point".Science Advances.4(2): eaat2340.Bibcode:2018SciA....4.2340L.doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat2340.PMC5821491.PMID29492460.

- ^Bochow, Nils; Boers, Niklas (October 6, 2023)."The South American monsoon approaches a critical transition in response to deforestation".Science Advances.9(40): eadd9973.Bibcode:2023SciA....9D9973B.doi:10.1126/sciadv.add9973.ISSN2375-2548.PMC10550231.PMID37792950.

- ^Kirby, Kathryn R.; Laurance, William F.; Albernaz, Ana K.; Schroth, Götz; Fearnside, Philip M.; Bergen, Scott; M. Venticinque, Eduardo; Costa, Carlos da (2006)."The future of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon"(PDF).Futures.38(4): 432–453.CiteSeerX10.1.1.573.1317.doi:10.1016/j.futures.2005.07.011.Archived(PDF)from the original on July 22, 2018.RetrievedOctober 27,2017.

- ^abWatkins and Griffiths, J. (2000). Forest Destruction and Sustainable Agriculture in the Brazilian Amazon: a Literature Review (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Reading, 2000). Dissertation Abstracts International, 15–17

- ^Williams, M.(2006).Deforesting the Earth: From Prehistory to Global Crisis(Abridged ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0-226-89947-3.

- ^"Impacts and Causes of Deforestation in the Amazon Basin".kanat.jsc.vsc.edu.Archived fromthe originalon June 15, 2013.RetrievedMarch 6,2013.

- ^Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) (2004)

- ^Steinfeld, Henning; Gerber, Pierre; Wassenaar, T.D.; Castel, Vincent (2006).Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.ISBN978-92-5-105571-7.Archivedfrom the original on July 26, 2008.RetrievedAugust 19,2008.

- ^Margulis, Sergio (2004).Causes of Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon(PDF).Washington, DC: The World Bank.ISBN978-0-8213-5691-3.Archived(PDF)from the original on September 10, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 4,2008.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^"Research paper of Leydimere Oliveira on the amazon".Archived fromthe originalon August 3, 2013.

- ^Barreto, P.; Souza Jr. C.; Noguerón, R.; Anderson, A. & Salomão, R. 2006.Human Pressure on the Brazilian Amazon Forests[permanent dead link].Imazon.Retrieved September 28, 2006. (TheImazonArchivedSeptember 1, 2004, at theWayback Machineweb site contains many resources relating to the Brazilian Amazonia.)

- ^"INPE: Estimativas Anuais desde 1988 até 2009".inpe.br.Archived fromthe originalon November 30, 2010.RetrievedNovember 3,2010.

- ^"Oil Drilling Contaminated Western Amazon".livesciences.com.June 13, 2014.Archivedfrom the original on February 18, 2019.RetrievedFebruary 17,2019.

- ^"Oil and Gas Extraction in the Amazon".wwf.panda.org.Archivedfrom the original on February 18, 2019.RetrievedFebruary 17,2019.

- ^"EU urged to halt trade talks with S. America over Brazil abuses".France 24.June 18, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on August 25, 2019.RetrievedAugust 25,2019.

- ^"We must not barter the Amazon rainforest for burgers and steaks".The Guardian.July 2, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on August 24, 2019.RetrievedAugust 25,2019.

- ^"Deforestation in Brazil's Amazon at highest level since 2006".Reuters/The Guardian.November 18, 2021.Archivedfrom the original on November 18, 2021.RetrievedJuly 3,2022.

- ^"Brazil: Amazon sees worst deforestation levels in 15 years".BBC News.November 19, 2021.Archivedfrom the original on July 15, 2022.RetrievedJuly 3,2022.

- ^"'Record number of fires' in Brazilian rainforest ".BBC News Online.BBC Online.BBC.August 21, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on August 22, 2019.RetrievedAugust 21,2019.

- ^Yeung, Jessie; Alvarado, Abel (August 21, 2019)."Brazil's Amazon rainforest is burning at a record rate".CNN.Turner Broadcasting System, Inc.Archivedfrom the original on August 14, 2020.RetrievedAugust 21,2019.

- ^Garrand, Danielle (August 20, 2019)."Parts of the Amazon rainforest are on fire – and smoke can be spotted from space".cbsnews.com.CBS Interactive Inc.Archivedfrom the original on August 27, 2019.RetrievedAugust 21,2019.

- ^"Record-breaking number of fires burn in Brazil's Amazon".CNBC.NBCUniversal.August 21, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on July 25, 2020.RetrievedAugust 21,2019.

- ^"Brazil registers huge spike in Amazon deforestation".Deutsche Welle.July 3, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on July 25, 2020.RetrievedAugust 22,2019.

- ^Melillo, J.M.; McGuire, A.D.; Kicklighter, D.W.; Moore III, B.; Vörösmarty, C.J.; Schloss, A.L. (May 20, 1993). "Global climate change and terrestrial net primary production".Nature.363(6426): 234–240.Bibcode:1993Natur.363..234M.doi:10.1038/363234a0.S2CID4370074.

- ^abTian, H.; Melillo, J.M.; Kicklighter, D.W.; McGuire, A.D.; Helfrich III, J.; Moore III, B.; Vörösmarty, C.J. (July 2000)."Climatic and biotic controls on annual carbon storage in Amazonian ecosystems"(PDF).Global Ecology and Biogeography.9(4): 315–335.Bibcode:2000GloEB...9..315T.doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00198.x.S2CID84534340.Archived(PDF)from the original on April 21, 2021.

- ^Fox, Alex (March 26, 2021)."The Amazon Rainforest Now Emits More Greenhouse Gases Than It Absorbs".Smithsonian Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on April 7, 2021.RetrievedApril 8,2021.

- ^Katarina, Zimmer (August 28, 2019)."Why the Amazon doesn't really produce 20% of the world's oxygen".National Geographic.Archived fromthe originalon February 18, 2021.RetrievedOctober 8,2021.

- ^Cox, Betts, Jones, Spall and Totterdell. 2000."Acceleration of global warming due to carbon-cycle feedbacks in a coupled climate model"ArchivedAugust 18, 2020, at theWayback Machine.Nature,November 9, 2000. (subscription required)

- ^Radford, T. 2002."World may be warming up even faster"ArchivedAugust 18, 2020, at theWayback Machine.The Guardian.

- ^Banerjee, Onil; Cicowiez, Martin; Macedo, Marcia N; Malek, Žiga; Verburg, Peter H; Goodwin, Sean; Vargas, Renato; Rattis, Ludmila; Bagstad, Kenneth J; Brando, Paulo M; Coe, Michael T; Neill, Christopher; Marti, Octavio Damiani; Murillo, Josué Ávila (December 1, 2022)."Can we avert an Amazon tipping point? The economic and environmental costs".Environmental Research Letters.17(12): 125005.Bibcode:2022ERL....17l5005B.doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aca3b8.hdl:1871.1/949d3af3-f463-40cc-90ab-1f9ff3060125.ISSN1748-9326.S2CID253666282.

- ^Houghton, J.T.et al.2001."Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis"ArchivedMay 7, 2006, at theWayback Machine.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- ^Peters, C.M.; Gentry, A.H.; Mendelsohn, R.O. (1989). "Valuation of an Amazonian forest".Nature.339(6227): 656–657.Bibcode:1989Natur.339..655P.doi:10.1038/339655a0.S2CID4338510.

- ^Dean, Bartholomew. (2003) State Power and Indigenous Peoples in Peruvian Amazonia: A Lost Decade, 1990–2000. InThe Politics of Ethnicity Indigenous Peoples in Latin American StatesDavid Maybury-Lewis,Ed.Harvard University Press

- ^Cormier, L. (April 16, 2006)."A Preliminary Review of Neotropical Primates in the Subsistence and Symbolism of Indigenous Lowland South American Peoples".Ecological and Environmental Anthropology.2(1): 14–32. Archived fromthe originalon December 21, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 4,2008.

- ^"Ecuador Amazon tribe win first victory against oil companies".Devdiscourse. April 27, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on July 25, 2020.RetrievedApril 28,2019.

- ^"Ecuador court rules Amazon rainforest can't be sold to oil companies".Newshub. Reuters. July 13, 2019. Archived fromthe originalon July 19, 2019.RetrievedJuly 19,2019.

- ^"US and Brazil agree to Amazon development".BBC.September 14, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on March 7, 2021.RetrievedSeptember 15,2020.

- ^abCovey, Kristofer; Soper, Fiona; Pangala, Sunitha; Bernardino, Angelo; Pagliaro, Zoe; Basso, Luana; Cassol, Henrique; Fearnside, Philip; Navarrete, Diego; Novoa, Sidney; Sawakuchi, Henrique; Lovejoy, Thomas; Marengo, Jose; Peres, Carlos A.; Baillie, Jonathan; Bernasconi, Paula; Camargo, Jose; Freitas, Carolina; Hoffman, Bruce; Nardoto, Gabriela B.; Nobre, Ismael; Mayorga, Juan; Mesquita, Rita; Pavan, Silvia; Pinto, Flavia; Rocha, Flavia; de Assis Mello, Ricardo; Thuault, Alice; Bahl, Alexis Anne; Elmore, Aurora (2021)."Carbon and Beyond: The Biogeochemistry of Climate in a Rapidly Changing Amazon".Frontiers in Forests and Global Change.4.Bibcode:2021FrFGC...4.8401C.doi:10.3389/ffgc.2021.618401.ISSN2624-893X.

Available underCC BY 4.0ArchivedOctober 16, 2017, at theWayback Machine.

Available underCC BY 4.0ArchivedOctober 16, 2017, at theWayback Machine.

- ^David Adam (March 11, 2009)."Amazon could shrink by 85% due to climate change, scientists say".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on April 14, 2020.RetrievedDecember 11,2016.

- ^Leal, C.G.; Lennox, G.D.; Ferraz, S.F.B.; Ferreira, J.; Gardner, T.A.; Thomson, J.R.; Berenguer, E.; Lees, A.C.; Hughes, R.M.; MackNally, R.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Brito, J.G.; Castello, L.; Garret, R.D.; Hamada, N.; Juen, L.; Leitão, R.P.; Louzada, J.; Morello, T.M.; Moura, N.G.; Nessimian, J.L.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B.; Oliveira, V.H.F.; Oliveira, V.C.; Parry, L.; Pompeu, P.S.; Solar, R.R.C.; Zuanon, J.; Barlow, J. (2020)."Integrated terrestrial-freshwater planning doubles conservation of tropical aquatic species"(PDF).Science.370(6512): 117–121.Bibcode:2020Sci...370..117L.doi:10.1126/science.aba7580.PMID33004520.S2CID222080850.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on July 15, 2021.

- ^Lovejoy, Thomas E.; Nobre, Carlos (December 20, 2019)."Amazon tipping point: Last chance for action".Science Advances.5(12): eaba2949.Bibcode:2019SciA....5A2949L.doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba2949.ISSN2375-2548.PMC6989302.PMID32064324.

- ^Watts, Jonathan (November 28, 2017)."The Amazon effect: how deforestation is starving São Paulo of water".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on June 7, 2020.RetrievedNovember 8,2018.

- ^Verchot, Louis (January 29, 2015)."The science is clear: Forest loss behind Brazil's drought".Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).Archivedfrom the original on August 9, 2020.RetrievedNovember 8,2018.

- ^E. Lovejoy, Thomas; Nobre, Carlos (February 21, 2018)."Amazon Tipping Point".Science Advances.4(2): eaat2340.Bibcode:2018SciA....4.2340L.doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat2340.PMC5821491.PMID29492460.

- ^Fox, Alex."The Amazon Rainforest Now Emits More Greenhouse Gases Than It Absorbs".Smithsonian Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on April 7, 2021.RetrievedApril 19,2021.

- ^Gatti, Luciana V.; Basso, Luana S.; Miller, John B.; Gloor, Manuel; Gatti Domingues, Lucas; Cassol, Henrique L. G.; Tejada, Graciela; Aragão, Luiz E. O. C.; Nobre, Carlos; Peters, Wouter; Marani, Luciano (July 14, 2021)."Amazonia as a carbon source linked to deforestation and climate change".Nature.595(7867): 388–393.Bibcode:2021Natur.595..388G.doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03629-6.ISSN0028-0836.PMID34262208.S2CID235906356.Archivedfrom the original on July 15, 2021.RetrievedJuly 15,2021.

- ^Einhorn, Catrin (February 4, 2022)."Ecuador Court Gives Indigenous Groups a Boost in Mining and Drilling Disputes".The New York Times.The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on February 6, 2022.RetrievedFebruary 6,2022.

- ^"Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon falls 22% in 2023".Mongabay.November 11, 2023.RetrievedNovember 13,2023.

- ^Spring, Jake (November 29, 2023)."Climate boost: 2023 Amazon deforestation drops 55.8%, study finds".The NRI Nation.Reuters.RetrievedDecember 3,2023.

- ^"Deforestation in Brazilian Amazon halved in 2023".Phys.org.RetrievedJanuary 9,2024.

- ^Wynne, R.H.; Joseph, K.A.; Browder, J.O.; Summers, P.M. (2007)."A Preliminary Review of Neotropical Primates in the Subsistence and Symbolism of Indigenous Lowland South American Peoples".International Journal of Remote Sensing.28(6): 1299–1315.Bibcode:2007IJRS...28.1299W.doi:10.1080/01431160600928609.S2CID128603494.Archived fromthe originalon December 21, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 4,2008.

- ^Asner, Gregory P.; Knapp, David E.; Cooper, Amanda N.; Bustamante, Mercedes M.C.; Olander, Lydia P. (June 2005)."Ecosystem Structure throughout the Brazilian Amazon from Landsat Observations and Automated Spectral Unmixing".Earth Interactions.9(1): 1–31.Bibcode:2005EaInt...9g...1A.doi:10.1175/EI134.1.S2CID31023189.

- ^Isaacson, Andy."With the Help of GPS, Amazonian Tribes Reclaim the Rain Forest".Wired.ISSN1059-1028.RetrievedAugust 11,2023.

- ^Kuplich, Tatiana M. (October 2006). "Classifying regenerating forest stages in Amazônia using remotely sensed images and a neural network".Forest Ecology and Management.234(1–3): 1–9.doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2006.05.066.

- ^"Amazon Drought Worst in 100 Years".www.ens-newswire.com.Archived fromthe originalon November 15, 2019.RetrievedJuly 25,2006.

- ^Drought Threatens Amazon Basin – Extreme conditions felt for second year runningArchivedMay 11, 2020, at theWayback Machine,Paul Brown,The Guardian,July 16, 2006. Retrieved August 23, 2014

- ^"Amazon rainforest 'could become a desert'"ArchivedAugust 6, 2006, at theWayback Machine,The Independent,July 23, 2006. Retrieved September 28, 2006.

- ^"Dying Forest: One year to save the Amazon"ArchivedSeptember 25, 2015, at theWayback Machine,The Independent,July 23, 2006. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^Nobre, Carlos; Lovejoy, Thomas E. (February 1, 2018)."Amazon Tipping Point".Science Advances.4(2): eaat2340.Bibcode:2018SciA....4.2340L.doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat2340.ISSN2375-2548.PMC5821491.PMID29492460.

- ^Stockholm Resilience Centre (October 5, 2020)."40% of Amazon could now exist as rainforest or savanna-like ecosystems".phys.org.Archivedfrom the original on October 8, 2020.RetrievedOctober 6,2020.

- ^Boulton, Chris A.; Lenton, Timothy M.; Boers, Niklas (March 7, 2022)."Pronounced loss of Amazon rainforest resilience since the early 2000s".Nature Climate Change.12(3): 271–278.Bibcode:2022NatCC..12..271B.doi:10.1038/s41558-022-01287-8.ISSN1758-6798.S2CID247255222.

- ^"Climate change a threat to Amazon rainforest, warns WWF"ArchivedJune 14, 2020, at theWayback Machine,World Wide Fund for Nature,March 22, 2006. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^2010 Amazon drought record: 8 Gt extra CO2ArchivedMarch 27, 2019, at theWayback Machine,Rolf Schuttenhelm,Bits Of Science,February 4, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2014

- ^"Amazon drought 'severe' in 2010, raising warming fears"ArchivedApril 15, 2016, at theWayback Machine,BBC News, February 3, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2014

- ^Abraham, John (August 3, 2017)."Study finds human influence in the Amazon's third 1-in-100 year drought since 2005".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on October 31, 2019.RetrievedAugust 8,2017.

- ^Casado, Letícia; Londoño, Ernesto (July 28, 2019)."Under Brazil's Far Right Leader, Amazon Protections Slashed and Forests Fall".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on August 18, 2020.RetrievedJuly 28,2019.

- ^"Scientists fear deforestation, fires and Covid-19 could create a 'perfect storm' in the Amazon".CNN. June 19, 2020.Archivedfrom the original on July 25, 2020.RetrievedJune 20,2020.

- ^"Brazil experiences worst start to Amazon fire season for 10 years".The Guardian.August 13, 2020.Archivedfrom the original on August 14, 2020.RetrievedAugust 13,2020.

- ^"Brazil's Bolsonaro calls surging Amazon fires a 'lie'".Reuters.August 11, 2020.Archivedfrom the original on August 12, 2020.RetrievedAugust 11,2020.

- ^"Brazil's Amazon rainforest suffers worst fires in a decade".The Guardian.October 1, 2020.Archivedfrom the original on October 2, 2020.RetrievedOctober 2,2020.

- ^"Campaigners' anger after huge surge in rainforest blazes".Sky News.Archivedfrom the original on November 7, 2020.RetrievedNovember 5,2020.

- ^"Silvopasture could tackle Colombian Amazon's high deforestation rates and help achieve COP26 targets".Phys.org.University of Bristol.RetrievedMay 30,2023.

- ^"Ecotourism could help the Amazon reduce deforestation and handle climate change".Archivedfrom the original on May 18, 2021.RetrievedMay 18,2021.

- ^"Community-Based Ecotourism in the Mamirauá Reserve: evaluation of product quality and reflections regarding the economic and financial feasibility of the activity".RetrievedMarch 19,2022.

- ^"Our ecolodges".Archivedfrom the original on May 18, 2021.RetrievedMay 18,2021.

- ^FREITAS, TATIANA."Brazilian banks are denying credit to meatpackers that deal in beef illegally raised in the Amazon rainforest".Fortune.RetrievedJune 1,2023.

- ^Ziolla Menezes, Fabiane (May 30, 2023)."BNDES to join anti-deforestation effort from banks".The Brazilian Report.RetrievedJune 1,2023.

- ^"Deforestation in Colombia Down 70 Percent So Far This Year".Yale Environment 360.RetrievedNovember 13,2023.

Further reading

- Bunker, S.G. (1985).Underdeveloping the Amazon: Extraction, Unequal Exchange, and the Failure of the Modern State.University of Illinois Press.

- Cleary, David (2000). "Towards an Environmental History of the Amazon: From Pre-history to the Nineteenth Century".Latin American Research Review.36(2): 64–96.PMID18524060.

- Dean, Warren(1976).Rio Claro: A Brazilian Plantation System, 1820–1920.Stanford University Press.

- Dean, Warren (1997).Brazil and the Struggle for Rubber: A Study in Environmental History.Cambridge University Press.

- Goulding, Michael (2021).The Fishes and the Forest: Explorations in Amazonian Natural History.Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.ISBN9780520316126.

- Hecht, Susanna and Alexander Cockburn (1990).The Fate of the Forest: Developers, Destroyers, and Defenders of the Amazon.New York: Harper Perennial.

- Hochstetler, K. and M. Keck (2007).Greening Brazil: Environmental Activism in State and Society.Duke University Press.ISBN978-0822340317

- Revkin, A. (1990).The Burning Season: The Murder of Chico Mendes and the Fight for the Amazon Rain Forest.Houghton Mifflin.ISBN9780002158862

- Wade, Lizzie (2015). "Drones and satellites spot lost civilizations in unlikely places".Science News.doi:10.1126/science.aaa7864.

- Weinstein, Barbara (1983).The Amazon Rubber Boom 1850–1920.Stanford University Press.ISBN0804711682

- Sheil, D.; Wunder, S. (2002)."The value of tropical forest to local communities: complications, caveats, and cautions"(PDF).Conservation Ecology.6(2): 9.doi:10.5751/ES-00458-060209.hdl:10535/2768.Archived(PDF)from the original on January 24, 2021.RetrievedSeptember 25,2019.

External links

- Journey into Amazonia

- The Amazon: The World's Largest Rainforest

- WWF in the Amazon rainforest

- Amazonia.org.brGood daily updated Amazon information database on the web, held by Friends of The Earth – Brazilian Amazon.

- Seasons in the Amazon and river levelsArchivedMay 2, 2023, at theWayback Machine

- amazonia.orgSustainable Development in the Extractive Reserve of the Baixo Rio Branco – Rio Jauaperi – Brazilian Amazon.

- Amazon Rainforest NewsOriginal news updates on the Amazon.

- Amazon-Rainforest.orgInformation about the Amazon rainforest, its people, places of interest, and how everyone can help.

- Conference: Climate change and the fate of the Amazon.Podcasts of talks given atOriel College,University of Oxford, March 20–22, 2007.

- Deadhumpback whalecalfin the Amazon

- Amazon rainforest

- Amazon basin

- Amazon biome

- Amazon River

- Ecoregions of South America

- Natural history of Peru

- Natural history of Brazil

- Natural history of Ecuador

- Neotropical ecoregions

- Rainforests

- Regions of South America

- Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests

- Forestry in South America

- Droughts in South America

![Climate change disturbances of rainforests.[104]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1b/Climate_change_disturbances_of_rainforests_infographic.jpg/223px-Climate_change_disturbances_of_rainforests_infographic.jpg)