Rickettsia parkeri

| Rickettsia parkeri | |

|---|---|

| |

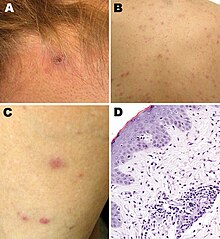

| Rickettsia parkeririckettsiosis skin lesions: A -escharafter tick bite on neck; B, C -papulovesicularrash on back and leg; D -micrographofbiopsyspecimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Alphaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Rickettsiales |

| Family: | Rickettsiaceae |

| Genus: | Rickettsia |

| Species group: | Spotted fever group |

| Species: | R. parkeri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Rickettsia parkeri Lackmanet al.,1965

| |

Rickettsia parkeri(abbreviatedR. parkeri) is agram-negativeintracellular bacterium. The organism is found in theWestern Hemisphereand is transmitted via the bite ofhard ticksof the genusAmblyomma.R. parkericauses mildspotted feverdisease in humans, whose most common signs and symptoms are fever, anescharat the site of tick attachment, rash, headache, and muscle aches.Doxycyclineis the most common drug used to reduce the symptoms associated with disease.

Biology[edit]

R. parkeriis classified in the spotted fever group of the genusRickettsia.[1][2]Genetically, its close relatives includeR. africae,R. sibirica,R. conorii,R. rickettsii,R. peacockii,andR. honei.[1]

The organism has been isolated from numerous species of ticks in the genusAmblyomma:A. americanumin the United States;A. aureolatumin Brazil;A. maculatumin Mexico, Peru, and the United States;A. nodosumin Brazil;A. ovalein Brazil and Mexico;A. parvitarsumin Argentina and Chile;A. tigrinumin Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Uruguay; andA. tristein Argentina, Brazil, the United States, and Uruguay.[2][3][4][5]Different ticks may carry differentstrainsof the organism.R. parkerisensu stricto ( "in the strict sense" ) is found inA. maculatumandA. triste;R. parkeristrain NOD, inA. nodosum;R. parkeristrain Parvitarsum, inA. parvitarsum;andR. parkeristrain Atlantic rainforest, inA. aureolatumandA. ovale.[2]

Human infections[edit]

The first report of a confirmed human case of infection withR. parkeriwas published in 2004.[6][7]The person was infected in the state of Virginia in the United States.[6]Other confirmed or probable human cases have been reported to have acquired infection elsewhere in the United States (e.g., Arizona, Georgia, and Mississippi), as well as in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Uruguay.[8][9]Terms used to describe human infection withR. parkeriinclude "American boutonneuse fever" because of its similarity toboutonneuse fevercaused byRickettsia conorii;[10]"American tick bite fever"because of its similarity toAfrican tick bite fevercaused byRickettsia africae;[11]"Tidewater spotted fever," after theTidewater regionin the eastern United States;[12]and "Rickettsia parkeririckettsiosis"or"R. parkeririckettsiosis. "[7][12]

Epidemiology[edit]

Of all human cases documented in the medical literature, 87% were 18-64 years of age, and most cases were male.[8]Brazil, Argentina, and the United States accounted for the majority of cases in the medical literature.[8]In the United States, most of the 40 cases reported to theCenters for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC) as of 2016 became infected between the months of July and September.[13]: 5–6

Diagnosis[edit]

The CDC recommendspolymerase chain reaction(PCR) of a biopsy or swab of an eschar, or PCR of a biopsy of a rash, for diagnosis ofR. parkeriinfection.[13]: 27 In addition, indirectimmunofluorescenceantibody (IFA) assays using paired acute and convalescent sera can be used.[13]: 27

Clinical manifestations[edit]

A 2008 study compared 12R. parkericases with 208Rocky Mountain spotted fevercases caused byR. rickettsii.[7]Although bothR. parkeriandR. rickettsiicaused fever, rash, myalgia, and headache,R. parkericaused eschars andR. rickettsiidid not.[7]Furthermore, the percentage of patients hospitalized was lower forR. parkerithan forR. rickettsii(33% vs 78%), andR. parkeriled to no deaths whileR. rickettsiiled to death in 7% of cases.[7]

A 2021systematic reviewof 32 confirmed and 45 probable cases of human infection withR. parkeridetermined that 94% of the confirmed cases had fever, 91% an eschar, 72% a rash, 56% headache, and 56%myalgia,with similar percentages among the probable cases.[8]The rash was most frequently described as papular or macular.[8]Among the confirmed and probable cases, the most common treatment was doxycycline, followed bytetracycline.[8]Although 9% of all the cases were hospitalized, there was a "100% rate of clinical recovery."[8]

History[edit]

In 1939, Ralph R. Parker, director of theRocky Mountain Laboratory,and others published a paper on "a rickettsia-like infectious agent."[7][14]The agent, found inAmblyomma maculatumticks collected from cows in Texas, produced mild disease in guinea pigs.[7][14]In 1965, Lackman and others named the rickettsial organismR. parkeriafter Parker.[2][15]

References[edit]

- ^abPerlman SJ, Hunter MS, Zchori-Fein E (2006)."The emerging diversity ofRickettsia".Proc Biol Sci.273(1598): 2097–2106.doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3541.PMC1635513.PMID16901827.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abcdNieri-Bastos FA, Marcili A, De Sousa R, Paddock CD, Labruna MB (2018)."Phylogenetic evidence for the existence of multiple strains ofRickettsia parkeriin the New World ".Appl Environ Microbiol.84(8): e02872–17.Bibcode:2018ApEnM..84E2872N.doi:10.1128/AEM.02872-17.PMC5881050.PMID29439989.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Cohen SB, Yabsley MJ, Garrison LE, Freye JD, Dunlap BG, Dunn JR; et al. (2009)."Rickettsia parkeriinAmblyomma americanumticks, Tennessee and Georgia, USA ".Emerg Infect Dis.15(9): 1471–3.doi:10.3201/eid1509.090330.PMC2819870.PMID19788817.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Delgado-de la Mora J, Sánchez-Montes S, Licona-Enríquez JD, Delgado-de la Mora D, Paddock CD, Beati L; et al. (2019)."Rickettsia parkeriandCandidatusRickettsia andeanae in Tick of theAmblyomma maculatumGroup, Mexico ".Emerg Infect Dis.25(4): 836–838.doi:10.3201/eid2504.181507.PMC6433039.PMID30882330.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Sánchez-Montes S, Ballados-González GG, Hernández-Velasco A, Zazueta-Islas HM, Solis-Cortés M, Miranda-Ortiz H; et al. (2019)."Molecular Confirmation ofRickettsia parkeriinAmblyomma ovaleTicks, Veracruz, Mexico ".Emerg Infect Dis.25(12): 2315–2317.doi:10.3201/eid2512.190964.PMC6874242.PMID31742525.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abPaddock CD, Sumner JW, Comer JA, Zaki SR, Goldsmith CS, Goddard J; et al. (2004)."Rickettsia parkeri:a newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States ".Clin Infect Dis.38(6): 805–811.doi:10.1086/381894.PMID14999622.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abcdefgPaddock CD, Finley RW, Wright CS, Robinson HN, Schrodt BJ, Lane CC; et al. (2008)."Rickettsia parkeririckettsiosis and its clinical distinction from Rocky Mountain spotted fever ".Clin Infect Dis.47(9): 1188–1196.doi:10.1086/592254.PMID18808353.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abcdefgSilva-Ramos CR, Hidalgo M, Faccini-Martínez ÁA (2021). "Clinical, epidemiological, and laboratory features ofRickettsia parkeririckettsiosis: A systematic review ".Ticks Tick-Borne Dis.12(4): 101734.doi:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2021.101734.PMID33989945.S2CID234596034.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Torres-Castro M, Sánchez-Montes S, Colunga-Salas P, Noh-Pech H, Reyes-Novelo E, Rodríguez-Vivas RI (2022). "Molecular confirmation ofRickettsia parkeriin humans from Southern Mexico ".Zoonoses Public Health.69(4): 382–386.doi:10.1111/zph.12927.PMID35142079.S2CID246701684.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Goddard J, Paddock CD (2005)."Observations on distribution and seasonal activity of the Gulf Coast tick in Mississippi".J Med Entomol.42(2): 176–179.doi:10.1093/jmedent/42.2.176.PMID15799527.

- ^Iweriebor BC, Nqoro A, Obi CL (2020)."Rickettsia africaean agent of African tick bite fever in ticks collected from domestic animals in Eastern Cape, South Africa ".Pathogens.9(8): 631.doi:10.3390/pathogens9080631.PMC7459594.PMID32748891.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abWright CL, Nadolny RM, Jiang J, Richards AL, Sonenshine DE, Gaff HD; et al. (2011)."Rickettsia parkeriin Gulf Coast ticks, southeastern Virginia, USA ".Emerg Infect Dis.17(5): 896–8.doi:10.3201/eid1705.101836.PMC3321792.PMID21529406.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abcBiggs HM, Behravesh CB, Bradley KK, Dahlgren FS, Drexler NA, Dumler JS; et al. (2016)."Diagnosis and management of tickborne rickettsial diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and other spotted fever group rickettsioses, ehrlichioses, and anaplasmosis - United States".MMWR Recomm Rep.65(2): 1–44.doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6502a1.PMID27172113.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abParker RR, Kohls GM, Cox GW, Davis GE (1939)."Observations on an infectious agent fromAmblyomma maculatum".Public Health Rep.54(32): 1482–1484.doi:10.1086/592254.PMID18808353.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Lackman DB, Bell EJ, Stoenner HG, Pickens EG (1965). "The Rocky Mountain spotted fever group of rickettsias".Health Lab Sci.2:135–141.PMID14318051.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links[edit]

- "Rickettsia parkeririckettsiosis ".Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. January 10, 2019.