Ancient Greek literature

Ancient Greek literatureisliteraturewritten in theAncient Greeklanguage from the earliest texts until the time of theByzantine Empire.The earliest surviving works of ancient Greek literature, dating back to the earlyArchaic period,are the two epic poems theIliadand theOdyssey,set in an idealized archaic past today identified as having some relation to theMycenaean era.These two epics, along with theHomeric Hymnsand the two poems ofHesiod,theTheogonyandWorks and Days,constituted the major foundations of the Greek literary tradition that would continue into theClassical,Hellenistic,andRoman periods.

The lyric poetsSappho,Alcaeus,andPindarwere highly influential during the early development of the Greek poetic tradition.Aeschylusis the earliest Greek tragic playwright for whom any plays have survived complete.Sophoclesis famous for his tragedies aboutOedipus,particularlyOedipus the KingandAntigone.Euripidesis known for his plays which often pushed the boundaries of the tragic genre. The comedic playwrightAristophaneswrote in the genre ofOld Comedy,while the later playwrightMenanderwas an early pioneer ofNew Comedy.The historiansHerodotus of HalicarnassusandThucydides,who both lived during the fifth century BC, wrote accounts of events that happened shortly before and during their own lifetimes. The philosopherPlatowrote dialogues, usually centered around his teacherSocrates,dealing with various philosophical subjects, whereas his studentAristotlewrote numerous treatises, which later became highly influential.

Important later writers includedApollonius of Rhodes,who wroteThe Argonautica,an epic poem about the voyage of theArgonauts;Archimedes,who wrote groundbreaking mathematical treatises; andPlutarch,who wrote mainly biographies and essays. The second-century AD writerLucian of Samosatawas a Greek, who wrote primarily works ofsatire.[1]Ancient Greek literature has had a profound impact on laterGreek literatureand alsowestern literatureat large. In particular, manyancient Roman authorsdrew inspiration from their Greek predecessors. Ever since theRenaissance,European authors in general, includingDante Alighieri,William Shakespeare,John Milton,andJames Joyce,have all drawn heavily on classical themes and motifs.

Pre-classical and classical antiquity[edit]

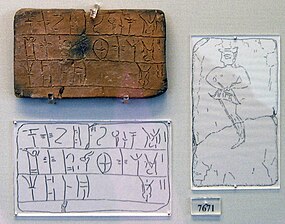

This period of Greek literature stretches fromHomeruntil the fourth century BC and the rise ofAlexander the Great.The earliest known Greek writings areMycenaean,written in theLinear Bsyllabary on clay tablets. These documents contain prosaic records largely concerned with trade (lists, inventories, receipts, etc.); no real literature has been discovered.[2][3]Michael VentrisandJohn Chadwick,the original decipherers of Linear B, state that literature almost certainly existed inMycenaean Greece,[3]but it was either not written down or, if it was, it was on parchment or wooden tablets, which did not survive thedestruction of the Mycenaean palaces in the twelfth century BC.[3]

Greek literature was divided into well-defined literary genres, each one having a compulsory formal structure, about bothdialectand metrics.[4]The first division was between prose and poetry. Within poetry there were three super-genres: epic, lyric and drama. The common European terminology about literary genres is directly derived from the ancient Greek terminology.[5]Lyric and drama were further divided into more genres: lyric in four (elegiac,iambic,monodic lyricandchoral lyric); drama in three (tragedy,comedyandpastoral drama).[6]Prose literature can largely be said to begin withHerodotus.[7]Over time, several genres of prose literature developed,[7]but the distinctions between them were frequently blurred.[7]

Epic poetry[edit]

At the beginning of Greek literature stand the two monumental works ofHomer,theIliadand theOdyssey.[8]: 1–3 The figure of Homer is shrouded in mystery. Although the works as they now stand are credited to him, it is certain that their roots reach far back before his time (seeHomeric Question).[8]: 15 TheIliadis a narrative of a single episode spanning over the course of a ten-day-period from near the end of the ten years of the Trojan War. It centers on the person ofAchilles,[9]who embodied the Greek heroic ideal.[10][8]: 3

TheOdysseyis an account of the adventures ofOdysseus,one of the warriors atTroy.[8]: 3 After ten years fighting the war, he spends another ten years sailing back home to his wife and family. Penelope was considered the ideal female; Homer depicted her as the ideal female based on her commitment, modesty, purity, and respect during her marriage to Odysseus. During his ten-year voyage, he loses all of his comrades and ships and makes his way home toIthacadisguised as a beggar. Both of these works were based on ancient legends.[8]: 15 TheHomeric dialectwas an archaic language based onIonic dialectmixed with some element ofAeolic dialectandAttic dialect,[11]the latter due to the Athenian edition of the 6th century BC. The epic verse was thehexameter.[12]

The other great poet of the preclassical period wasHesiod.[8]: 23–24 [13]Unlike Homer, Hesiod refers to himself in his poetry.[14]Nonetheless, nothing is known about him from any external source. He was a native ofBoeotiaincentral Greece,and is thought to have lived and worked around 700 BC.[15]Hesiod's two extant poems areWorks and Daysand theTheogony.Works and Daysis a faithful depiction of the poverty-stricken country life he knew so well, and it sets forth principles and rules for farmers. It vividly describes the ages of mankind, beginning with a long-pastGolden Age.[16]TheTheogonyis a systematic account of creation and of the gods.

The writings of Homer and Hesiod were held in extremely high regard throughout antiquity[13]and were viewed by many ancient authors as the foundationaltextsbehindancient Greek religion;[17]Homer told the story of aheroicpast, which Hesiod bracketed with a creation narrative and an account of the practical realities of contemporary daily life.[8]: 23–24

Lyric poetry[edit]

Lyric poetryreceived its name from the fact that it was originally sung by individuals or a chorus accompanied by the instrument called thelyre.Despite the name, the lyric poetry in this general meaning was divided in four genres, two of which were not accompanied bycithara,but by flute. These two latter genres wereelegiac poetryandiambic poetry.Both were written in theIonic dialect.Elegiac poems were written inelegiac coupletsand iambic poems were written iniambic trimeter.The first of the lyric poets was probablyArchilochus of Paros,7th century BC, the most important iambic poet.[18]Only fragments remain of his work, as is the case with most of the poets. The few remnants suggest that he was an embittered adventurer who led a very turbulent life.[19]

Many lyric poems were written in theAeolic dialect.Lyric poems often employed highly varied poetic meters. The most famous of all lyric poets were the so-called "Nine Lyric Poets".[20]Of all the lyric poets,SapphoofLesbos(c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was by far the most widely revered. In antiquity, her poems were regarded with the same degree of respect as the poems of Homer.[21]Only one of her poems, "Ode to Aphrodite",has survived to the present day in its original, completed form.[22]In addition to Sappho, her contemporaryAlcaeusofLesboswas also notable formonodiclyric poetry. The poetry written byAlcmanwas considered beautiful, even though he wrote exclusively in theDoric dialect,which was normally considered unpleasant to hear.[23]The later poetPindarofThebeswas renowned for hischorallyric poetry.[24]

Drama[edit]

All surviving works of Greek drama were composed by playwrights fromAthensand are written exclusively in theAttic dialect.[25]Choral performanceswere a common tradition in all Greek city-states.[25]The Athenians credited a man namedThespiswith having invented drama[25]by introducing the first actor, whose primary purpose was to interact with the leader of the chorus.[26]Later playwrights expanded the number of actors to three, allowing for greater freedom in storytelling.[27]

In the age that followed theGreco-Persian Wars,the awakened national spirit ofAthenswas expressed in hundreds of tragedies based on heroic and legendary themes of the past. The tragic plays grew out of simple choral songs and dialogues performed at festivals of the godDionysus.In the classical period, performances included three tragedies and one pastoral drama, depicting four different episodes of the same myth. Wealthy citizens were chosen to bear the expense of costuming and training the chorus as a public and religious duty. Attendance at the festival performances was regarded as an act of worship. Performances were held in the great open-air theater of Dionysus in Athens. The poets competed for the prizes offered for the best plays.[28]

All fully surviving Greek tragedies are conventionally attributed toAeschylus,SophoclesorEuripides.The authorship ofPrometheus Bound,which is traditionally attributed to Aeschylus,[29]andRhesus,which is traditionally attributed to Euripides, are, however, questioned.[30]There are seven surviving tragedies attributed to Aeschylus. Three of these plays,Agamemnon,The Libation-Bearers,andThe Eumenides,form a trilogy known as theOresteia.[31]One of these plays,Prometheus Bound,however, may actually be the work of Aeschylus's sonEuphorion.[32]

Seven works of Sophocles have survived, the most acclaimed of which are thethree Theban plays,which center around the story ofOedipusand his offspring.[33]The Theban Trilogy consists ofOedipus the King,Oedipus at Colonus,andAntigone.Although the plays are often called a "trilogy," they were written many years apart.Antigone,the last of the three plays sequentially, was actually first to be written, having been composed in 441 BC, towards the beginning of Sophocles's career.[34]Oedipus the King,the most famous of the three, was written around 429 BC at the midpoint of Sophocles's career.[Notes 1]Oedipus at Colonus,the second of the three plays chronologically, was actually Sophocles's last play and was performed in 401 BC, after Sophocles's death.[35]

There are nineteen surviving plays attributed toEuripides.The most well-known of these plays areMedea,Hippolytus,andBacchae.[36]Rhesusis sometimes thought to have been written by Euripides' son, or to have been a posthumous reproduction of a play by Euripides.[37]Euripides pushed the limits of the tragic genre and many of the elements in his plays were more typical of comedy than tragedy.[38]His playAlcestis,for instance, has often been categorized as a "problem play"or perhaps even as a work oftragicomedyrather than a true tragedy due to its comedic elements and the fact that it has a happy ending.[39][40]

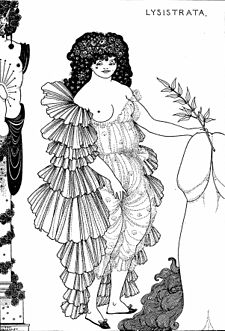

Like tragedy, comedy arose from a ritual in honor ofDionysus,but in this case the plays were full of frank obscenity, abuse, and insult. AtAthens,the comedies became an official part of the festival celebration in 486 BC, and prizes were offered for the best productions. As with the tragedians, few works remain of the great comedic writers. The only complete surviving works of classical comedy are eleven plays written by the playwrightAristophanes.[41]These are a treasure trove of comic presentation. He poked fun at everyone and every institution. InThe Birds,he ridiculesAthenian democracy.InThe Clouds,he attacks the philosopherSocrates.InLysistrata,he denounces war.[42]Aristophanes has been praised highly for his dramatic skill and artistry.John Lemprière'sBibliotheca Classicadescribes him as, quite simply, "the greatest comic dramatist in world literature: by his sideMolièreseems dull andShakespeareclownish. "[43]Of all Aristophanes's plays, however, the one that has received the most lasting recognition isThe Frogs,which simultaneously satirizes and immortalizes the two giants of Athenian tragedy: Aeschylus and Euripides. When it was performed for the first time at theLenaia Festivalin 405 BC, just one year after the death of Euripides, the Athenians awarded it first prize.[44]It was the only Greek play that was ever given anencoreperformance, which took place two months later at the City Dionysia.[45]Even today,The Frogsstill appeals to modern audiences. A commercially successful modernmusical adaptation of itwas performed on Broadway in 2004.[46]

The third dramatic genre was thesatyr play.Although the genre was popular, only one complete example of a satyr play has survived:CyclopsbyEuripides.[47]Large portions of a second satyr play,Ichneutaeby Sophocles, have been recovered from the site ofOxyrhynchusin Egypt among theOxyrhynchus Papyri.[48]

Historiography[edit]

Two notable historians who lived during the Classical Era wereHerodotusofHalicarnassusandThucydides.Herodotus is commonly called "The Father of History."[49]His bookThe Historiesis among the oldest works of prose literature in existence. Thucydides's bookHistory of the Peloponnesian Wargreatly influenced later writers and historians, including the author of the book ofActs of the Apostlesand theByzantine ErahistorianProcopiusofCaesarea.[50]

A third historian of ancient Greece,XenophonofAthens,began hisHellenicawhere Thucydides ended his work about 411 BC and carried his history to 362 BC.[51]Xenophon's most famous work is his bookThe Anabasis,a detailed, first-hand account of his participation in a Greek mercenary army that tried to help the Persian Cyrus expel his brother from the throne, another famous work relating to Persian history is hisCyropaedia.Xenophon also wrote three works in praise of the philosopherSocrates:The Apology of Socrates to the Jury,The Symposium,andMemorabilia.Although both Xenophon and Plato knew Socrates, their accounts are very different. Many comparisons have been made between the account of the military historian and the account of the poet-philosopher.[52]

Philosophy[edit]

Many important and influential philosophers lived during the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Among the earliest Greek philosophers were the three so-called "Milesian philosophers":Thales of Miletus,Anaximander,andAnaximenes.[53]Of these philosophers' writings, however, only one fragment from Anaximander preserved bySimplicius of Ciliciahas survived.[Notes 2][54]

Very little is known for certain about the life of the philosopherPythagoras of Samosand no writings by him have survived to the present day,[55]but an impressive corpus of poetic writings written by his pupilEmpedocles of Acragashas survived, making Empedocles one of the most widely attestedPre-Socratic philosophers.[56]A large number of fragments written by the philosophersHeraclitus of Ephesus[57]andDemocritus of Abderahave also survived.[58]

Of all the classical philosophers, however,Socrates,Plato,andAristotleare generally considered the most important and influential. Socrates did not write any books himself and modern scholars debate whether or not Plato's portrayal of him is accurate. Some scholars contend that many of his ideas, or at least a vague approximation of them, are expressed in Plato's earlysocratic dialogues.[59]Meanwhile, other scholars have argued that Plato's portrayal of Socrates is merely a fictional representation intended to expound Plato's own opinions who has very little to do with the historical figure of the same name.[60]The debate over the extent to which Plato's portrayal of Socrates represents the actual Socrates's ideas is known as theSocratic problem.[61][62]

Plato expressed his ideas through dialogues, that is, written works purporting to describe conversations between different individuals. Some of the best-known of these include:The Apology of Socrates,a purported record of the speech Socrates gave at his trial;[63]Phaedo,a description of the last conversation between Socrates and his disciples before his execution;[64]The Symposium,a dialogue over the nature oflove;[65]andThe Republic,widely regarded as Plato's most important work,[66][67]a long dialogue describing the ideal government.[68]

Aristotle of Stagira is widely considered to be one of the most important and influential philosophical thinkers of all time.[69]The first sentence of hisMetaphysicsreads: "All men by nature desire to know." He has, therefore, been called the "Father of those who know." His medieval discipleThomas Aquinasreferred to him simply as "the Philosopher". Aristotle was a student at Plato'sAcademy,and like his teacher, he wrote dialogues, or conversations. However, none of these exist today. The body of writings that have come down to the present probably represents lectures that he delivered at his own school in Athens, theLyceum.[70]Even from these books, the enormous range of his interests is evident: He explored matters other than those that are today considered philosophical; the extant treatises cover logic, the physical and biological sciences, ethics, politics, and constitutional government. Among Aristotle's most notable works arePolitics,Nicomachean Ethics,Poetics,On the Soul,andRhetoric.[71]

Hellenistic period[edit]

By 338 BC all of the Greekcity-statesexceptSpartahad been united byPhilip II of Macedon.[72]Philip's sonAlexander the Greatextended his father's conquests greatly. Athens lost its preeminent status as the leader of Greek culture, and it was replaced temporarily byAlexandria,Egypt.[73]

The city of Alexandria in northern Egypt became, from the 3rd century BC, the outstanding center of Greek culture. It also soon attracted a large Jewish population, making it the largest center for Jewish scholarship in the ancient world. TheSeptuagint,a Greek translation of theHebrew Biblewas reputed to have been initiated in Alexandria.Philo,aHellenistic Jewishphilosopher, operated out of Alexandria at the turn of theCommon Era.In addition, it later became a major focal point for the development ofChristian thought.TheMusaeum,or Shrine to the Muses, which included the library and school, was founded byPtolemy I.The institution was from the beginning intended as a great international school and library.[74]The library, eventually containing more than a half million volumes, was mostly in Greek. It was intended to serve as a repository for every work of classical Greek literature that could be found.[75]

Poetry[edit]

The genre of bucolic poetry was first developed by the poetTheocritus.[76]The RomanVirgillater wrote hisEcloguesin this genre.[77]Callimachus,a scholar at theLibrary of Alexandria,composed theAetia( "Causes" ),[78]a long poem written in four volumes ofelegiac coupletsdescribing the legendary origins of obscure customs, festivals, and names,[78]which he probably wrote in several stages over the course of many years in the third century BC.[78]TheAetiawas lost during the Middle Ages,[78]but, over the course of the twentieth century, much of it was recovered due to new discoveries of ancient papyri.[78]Scholars initially denigrated it as "second-rate", showing great learning, but lacking true "art".[78]Over the course of the century, scholarly appraisal of it greatly improved, with many scholars now seeing it in a much more positive light.[78]Callimachus also wrote short poems for special occasions and at least one short epic, theIbis,which was directed against his former pupil Apollonius.[79]He also compiled a prose treatise entitled thePinakes,in which he catalogued all the major works held in the Library of Alexandria.[80]

The Alexandrian poetApollonius of Rhodesis best known for his epic poem theArgonautica,which narrates the adventures ofJasonand his shipmates theArgonautson their quest to retrieve theGolden Fleecefrom the land ofColchis.[81]The poetAratuswrote the hexameter poemPhaenomena,a poetic rendition ofEudoxus of Cnidus's treatise on the stars written in the fourth century BC.[82]

Drama[edit]

During theHellenistic period,theOld Comedyof the Classical Era was replaced byNew Comedy.The most notable writer of New Comedy was the Athenian playwrightMenander.None of Menander's plays have survived to the present day in their complete form, but one play,The Bad-Tempered Man,has survived to the present day in a near-complete form. Most of another play entitledThe Girl from Samosand large portions of another five have also survived.[83]

Historiography[edit]

The historianTimaeuswas born inSicilybut spent most of his life inAthens.[84]HisHistory,though lost, is significant because of its influence onPolybius.In 38 books it covered the history of Sicily and Italy to the year 264 BC, which is where Polybius begins his work. Timaeus also wrote theOlympionikai,a valuable chronological study of the Olympic Games.[85]

Ancient biography[edit]

Ancient biography,orbios,as distinct from modern biography, was a genre of Greek (and Roman) literature interested in describing the goals, achievements, failures, and character of ancient historical persons and whether or not they should be imitated. Authors of ancientbios,such as the works ofNeposandPlutarch'sParallel Livesimitated many of the same sources and techniques of the contemporary historiographies of ancient Greece, notably including the works ofHerodotusandThucydides.There were various forms of ancient biographies, including philosophical biographies that brought out the moral character of their subject (such asDiogenes Laertius'sLives of Eminent Philosophers), literary biographies which discussed the lives of orators and poets (such asPhilostratus'sLives of the Sophists), school and reference biographies that offered a short sketch of someone including their ancestry, major events and accomplishments, and death, autobiographies, commentaries and memoirs where the subject presents his own life, and historical/political biography focusing on the lives of those active in the military, among other categories.[86]

Science and mathematics[edit]

Eratosthenes of Alexandria(c.276 BC –c. 195/194 BC), wrote on astronomy and geography, but his work is known mainly from later summaries. He is credited with being the first person to measure the Earth's circumference. Much that was written by the mathematiciansEuclidandArchimedeshas been preserved. Euclid is known for hisElements,much of which was drawn from his predecessorEudoxus of Cnidus.TheElementsis a treatise on geometry, and it has exerted a continuing influence on mathematics. From Archimedes several treatises have come down to the present. Among them areMeasurement of the Circle,in which he worked out the value of pi;The Method of Mechanical Theorems,on his work in mechanics;The Sand Reckoner;andOn Floating Bodies.Amanuscript of his worksis currently being studied.[87]

Prose fiction[edit]

Very little has survived of prose fiction from the Hellenistic Era.The Milesiakaby Aristides of Miletos was probably written during the second century BC.The Milesiakaitself has not survived to the present day in its complete form, but various references to it have survived. The book established a whole new genre of so-called "Milesian tales,"of whichThe Golden Assby the later Roman writerApuleiusis a prime example.[88][89]

Theancient Greek novelsChaereas and Callirhoe[90]by Chariton andMetiochus and Parthenope[91][92]were probably both written during the late first century BC or early first century AD, during the latter part of the Hellenistic Era. The discovery of several fragments of Lollianos'sPhoenician Talereveal the existence of a genre of ancient Greekpicaresque novel.[93]

Roman period[edit]

While the transition from city-state to empire affected philosophy a great deal, shifting the emphasis from political theory to personal ethics, Greek letters continued to flourish both under theSuccessors(especially the Ptolemies) and under Roman rule. Romans of literary or rhetorical inclination looked to Greek models, and Greek literature of all types continued to be read and produced both by native speakers of Greek and later by Roman authors as well. A notable characteristic of this period was the expansion of literary criticism as a genre, particularly as exemplified by Demetrius, Pseudo-Longinus and Dionysius of Halicarnassus. TheNew Testament,written by various authors in varying qualities ofKoine Greekalso hails from this period,[94][8]: 208–209 the most important works being theGospelsand theEpistles of Saint Paul.[95][8]: 208–213

Poetry[edit]

The poetQuintus of Smyrna,who probably lived during the late fourth century AD,[96][97]wrotePosthomerica,an epic poem narrating the story of the fall of Troy, beginning where theIliadleft off.[98]About the same time and in a similar Homeric style, an unknown poet composed theBlemyomachia,a now fragmentary epic about conflict between Romans andBlemmyes.[99]

The poetNonnusofPanopoliswrote theDionysiaca,the longest surviving epic poem from antiquity. He also wrote a poetic paraphrase ofThe Gospel of John.[100][101]Nonnus probably lived sometime during the late fourth century AD or early fifth century AD.[102][103]

Historiography[edit]

The historianPolybiuswas born about 200 BC. He was brought toRomeas a hostage in 168. In Rome he became a friend of the general Scipio Aemilianus. He probably accompanied the general to Spain and North Africa in the wars against Carthage. He was with Scipio at the destruction ofCarthagein 146.[104]

Diodorus Siculuswas a Greek historian who lived in the 1st century BC, around the time of Julius Caesar and Augustus. He wrote auniversal history,Bibliotheca Historica,in 40 books. Of these, the first five and the 11th through the 20th remain. The first two parts covered history through the early Hellenistic era. The third part takes the story to the beginning of Caesar's wars in Gaul, now France.[105]Dionysius of Halicarnassuslived late in the first century BC. His history of Rome from its origins to the First Punic War (264 to 241 BC) is written from a Roman point of view, but it is carefully researched. He also wrote a number of other treatises, includingOn Imitation,Commentaries on the Ancient Orators,andOn the Arrangement of Words.[106]

The historiansAppian of AlexandriaandArrian of Nicomediaboth lived in the second century AD.[107][108]Appian wrote on Rome and its conquests, while Arrian is remembered for his work on the campaigns of Alexander the Great. Arrian served in the Roman army. His book therefore concentrates heavily on the military aspects of Alexander's life. Arrian also wrote a philosophical treatise, theDiatribai,based on the teachings of his mentorEpictetus.

Best known of the late Greek historians to modern readers isPlutarchofChaeronea,who died about AD 119. HisParallel Livesof great Greek and Roman leaders has been read by every generation since the work was first published. His other surviving work is theMoralia,a collection of essays on ethical, religious, political, physical, and literary topics.[109][110]

During later times, so-called "commonplace books,"usually describing historical anecdotes, became quite popular. Surviving examples of this popular genre include works such asAulus Gellius'sAttic Nights,[111]Athenaeus of Naucratis'sDeipnosophistae,[112]andClaudius Aelianus'sDe Natura AnimaliumandVaria Historia.[113]

Science and mathematics[edit]

The physicianGalenlived during the 2nd century AD. He was a careful student of anatomy, and his works exerted a powerful influence on medicine for the next 1,400 years.Strabo,who died about AD 23, was a geographer and historian. HisHistorical Sketchesin 47 volumes has nearly all been lost. HisGeographical Sketchesremains the only existing ancient book covering the whole range of people and countries known to the Greeks and Romans through the time ofAugustus.[114]Pausanias,who lived in the 2nd century AD, was also a geographer.[115]HisDescription of Greeceis a travel guide describing the geography and mythic history of Greece during the second century. The book takes the form of a tour of Greece, starting inAthensand ending inNaupactus.[116]

The scientist of the Roman period who had the greatest influence on later generations was undoubtedly the astronomerPtolemy.He lived during the 2nd century AD,[117]though little is known of his life. His masterpiece, originally entitledThe Mathematical Collection,has come to the present under the titleAlmagest,as it was translated by Arab astronomers with that title.[118]It was Ptolemy who devised a detailed description of anEarth-centered universe,[119]a notion that dominated astronomical thinking for more than 1,300 years.[120]The Ptolemaic view of the universe endured untilCopernicus,Galileo,Kepler,and other early modern astronomers replaced it withheliocentrism.[121]

Philosophy[edit]

Epictetus(c.55 AD – 135 AD) was associated with the moral philosophy of theStoics.His teachings were collected by his pupil Arrian in theDiscoursesand theEncheiridion(Manual of Study).[122]

Diogenes Laërtius,who lived in the third century AD, wroteLives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers,a voluminous collection of biographies of nearly every Greek philosopher who ever lived. Unfortunately, Diogenes Laërtius often fails to cite his sources and many modern historians consider his testimony unreliable.[123]Nonetheless, in spite of this, he remains the only available source on the lives of many early Greek philosophers.[124]His book is not entirely without merit; it does preserve a tremendous wealth of information that otherwise would not have been preserved. His biography ofEpicurus,for instance, is of particularly high quality and contains three lengthy letters attributed to Epicurus himself, at least two of which are generally agreed to be authentic.[125]

Another major philosopher of his period wasPlotinus.He transformed Plato's philosophy into a school calledNeoplatonism.[126]HisEnneadshad a wide-ranging influence on European thought until at least the seventeenth century.[127]Plotinus's philosophy mainly revolved around the concepts ofnous,psyche,and the "One."[128]

After the rise of Christianity, many of the most important philosophers were Christians. The second-century Christian apologistJustin Martyr,who wrote exclusively in Greek, made extensive use of ideas from Greek philosophy, especiallyPlatonism.[129]Origen of Alexandria,the founder ofChristian theology,[130]also made extensive use of ideas from Greek philosophy[131]and was even able to hold his own against the pagan philosopherCelsusin his apologetic treatiseContra Celsum.[132]

Prose fiction[edit]

The Roman Period was the time when the majority of extant works of Greek prose fiction were composed. Theancient Greek novelsLeucippe and ClitophonbyAchilles Tatius[133][134]andDaphnis and ChloebyLongus[135]were both probably written during the early second century AD.Daphnis and Chloe,by far the most famous of the five surviving ancient Greek romance novels, is a nostalgic tale of two young lovers growing up in an idealized pastoral environment on the Greek island ofLesbos.[136]The Wonders Beyond ThulebyAntonius Diogenesmay have also been written during the early second century AD, although scholars are unsure of its exact date.The Wonders Beyond Thulehas not survived in its complete form, but a very lengthy summary of it written byPhotios I of Constantinoplehas survived.[137]The Ephesian TalebyXenophon of Ephesuswas probably written during the late second century AD.[135]

The satiristLucian of Samosatalived during the late second century AD. Lucian's works were incredibly popular during antiquity. Over eighty different writings attributed to Lucian have survived to the present day.[138]Almost all of Lucian's works are written in the heavilyAtticized dialectofancient Greek languageprevalent among the well-educated at the time. His bookThe Syrian Goddess,however, was written in a faux-Ionic dialect,deliberately imitating the dialect and style ofHerodotus.[139][140]Lucian's most famous work is the novelA True Story,which some authors have described as the earliest surviving work ofscience fiction.[141][142]His dialogueThe Lover of Liescontains several of the earliest knownghoststories[143]as well as the earliest known version of "The Sorcerer's Apprentice."[144]His letterThe Passing of Peregrinus,a ruthless satire againstChristians,contains one of the earliest pagan appraisals of early Christianity.[145]

TheAethiopicabyHeliodorus of Emesawas probably written during the third century AD.[146]It tells the story of a young Ethiopian princess named Chariclea, who is estranged from her family and goes on many misadventures across the known world.[147]Of all the ancient Greek novels, the one that attained the greatest level of popularity was theAlexander Romance,a fictionalized account of the exploits ofAlexander the Greatwritten in the third century AD. Eighty versions of it have survived in twenty-four different languages, attesting that, during the Middle Ages, the novel was nearly as popular as the Bible.[148]: 650–654 Versions of theAlexander Romancewere so commonplace in the fourteenth century thatGeoffrey Chaucerwrote that "...every wight that hath discrecioun / Hath herd somwhat or al of [Alexander's] fortune."[148]: 653–654

Legacy[edit]

Ancient Greek literature has had an enormous impact onwestern literatureas a whole.[149]Ancient Roman authors adopted various styles and motifs from ancient Greek literature. These ideas were later, in turn, adopted by other western European writers and literary critics.[149]Ancient Greek literature especially influenced laterGreek literature.For instance, the Greek novels influenced the later workHero and Leander,written byMusaeus Grammaticus.[150]Ancient Roman writers were acutely aware of the ancient Greek literary legacy and many deliberately emulated the style and formula of Greek classics in their own works. The Roman poetVergil,for instance, modeled his epic poem theAeneidon theIliadand theOdyssey.[151]

During theMiddle Ages,ancient Greek literature was largely forgotten in Western Europe. The medieval writerRoger Baconwrote that "there are not four men in Latin Christendom who are acquainted with the Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic grammars."[152]It was not until theRenaissancethat Greek writings were rediscovered by western European scholars.[153]During the Renaissance,Greekbegan to be taught in western European colleges and universities for the first time, which resulted in western European scholars rediscovering the literature of ancient Greece.[154]TheTextus Receptus,the first New Testament printed in the original Greek, was published in 1516 by the Dutch humanist scholarDesiderius Erasmus.[155]Erasmus also published Latin translations of classical Greek texts, including a Latin translation ofHesiod'sWorks and Days.[156]

The influence of classical Greek literature on modern literature is also evident. Numerous figures from classical literature and mythology appear throughoutThe Divine ComedybyDante Alighieri.[157]Plutarch'sLiveswere a major influence onWilliam Shakespeareand served as the main source behind his tragediesJulius Caesar,Antony and Cleopatra,andCoriolanus.[158]: 883–884 Shakespeare's comediesA Comedy of ErrorsandThe Twelfth Nightdrew heavily on themes from Graeco-RomanNew Comedy.[158]: 881–882 Meanwhile, Shakespeare's tragedyTimon of Athenswas inspired by a story written by Lucian[159]and his comedyPericles, Prince of Tyrewas based on an adaptation of the ancient Greek novelApollonius of Tyrefound inJohn Gower'sConfessio Amantis.[160]

John Milton's epic poemParadise Lostis written using a similar style to the two Homeric epics.[161]It also makes frequent allusions to figures from classical literature and mythology, using them as symbols to convey a Christian message.[162]Lucian'sA True Storywas part of the inspiration forJonathan Swift's novelGulliver's Travels.[158]: 545 Bulfinch's Mythology,a book onGreek mythologypublished in 1867 and aimed at a popular audience, was described by Carl J. Richard as "one of the most popular books ever published in the United States".[163]

George Bernard Shaw's playPygmalionis a modern, rationalized retelling of the ancient Greek legend ofPygmalion.[158]: 794 James Joyce's novelUlysses,heralded by critics as one of the greatest works of modern literature,[164][165]is a retelling of Homer'sOdysseyset in modern-dayDublin.[166][167]The mid-twentieth-century British authorMary Renaultwrote a number of critically acclaimed novels inspired by ancient Greek literature and mythology, includingThe Last of the WineandThe King Must Die.[168]

Even in works that do not consciously draw on Graeco-Roman literature, authors often employ concepts and themes originating in ancient Greece. The ideas expressed in Aristotle'sPoetics,in particular, have influenced generations of Western writers and literary critics.[169]A Latin translation of an Arabic version of thePoeticsbyAverroeswas available during the Middle Ages.[170]Common Greek literary terms still used today include:catharsis,[171]ethos,[172]anagnorisis,[173]hamartia,[174]hubris,[175]mimesis,[176]mythos,[177]nemesis,[178]andperipeteia.[179]

Notes[edit]

- ^Although Sophocles won second prize with the group of plays that includedOedipus Rex,its date of production is uncertain. The prominence of the Thebanplagueat the play's opening suggests to many scholars a reference to the plague that devastated Athens in 430 BC, and hence a production date shortly thereafter. See, for example,Knox, Bernard(1956). "The Date of theOedipus Tyrannusof Sophocles ".American Journal of Philology.77(2): 133–147.doi:10.2307/292475.JSTOR292475.

- ^Simplicius,Comments on Aristotle's Physics(24, 13):

- "Ἀναξίμανδρος [...] λέγει δ' αὐτὴν μήτε ὕδωρ μήτε ἄλλο τι τῶν καλουμένων εἶναι στοιχείων, ἀλλ' ἑτέραν τινὰ φύσιν ἄπειρον, ἐξ ἧς ἅπαντας γίνεσθαι τοὺς οὐρανοὺς καὶ τοὺς ἐν αὐτοῖς κόσμους· ἐξ ὧν δὲ ἡ γένεσίς ἐστι τοῖς οὖσι, καὶ τὴν φθορὰν εἰς ταῦτα γίνεσθαι κατὰ τὸ χρεών· διδόναι γὰρ αὐτὰ δίκην καὶ τίσιν ἀλλήλοις τῆς ἀδικίας κατὰ τὴν τοῦ χρόνου τάξιν, ποιητικωτέροις οὕτως ὀνόμασιν αὐτὰ λέγων. δῆλον δὲ ὅτι τὴν εἰς ἄλληλα μεταβολὴν τῶν τεττάρων στοιχείων οὗτος θεασάμενος οὐκ ἠξίωσεν ἕν τι τούτων ὑποκείμενον ποιῆσαι, ἀλλά τι ἄλλο παρὰ ταῦτα· οὗτος δὲ οὐκ ἀλλοιουμένου τοῦ στοιχείου τὴν γένεσιν ποιεῖ, ἀλλ' ἀποκρινομένων τῶν ἐναντίων διὰ τῆς αἰδίου κινήσεως."

References[edit]

- ^"Lucian | Greek writer".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2021-08-03.

Lucian [...] ancient Greek rhetorician, pamphleteer, and satirist.

- ^Chadwick, John (1967).The Decipherment of Linear B(Second ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 101.ISBN978-1-107-69176-6."The glimpse we have suddenly been given of the account books of a long-forgotten people..."

- ^abcVentris, Michael; Chadwick, John (1956).Documents in Mycenaean Greek.Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. xxix.ISBN978-1-107-50341-0.

- ^Heath, Malcolm, ed. (1997).Aristotle'sPoetics.Penguin Books.ISBN0-14-044636-2.

- ^Grendler, Paul F (2004).The Universities of the Italian Renaissance.Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 239.ISBN0-8018-8055-6.

- ^Frow, John (2007).Genre(Reprint ed.). Routledge. pp. 57–59.ISBN978-0-415-28063-1.

- ^abcEngels, Johannes (2008)."Chapter Ten: Universal History and Cultural Geography of theOikoumenein Herodotus'Historiaiand Strabo'sGeographika".In Pigoń, Jakub (ed.).The Children of Herodotus: Greek and Roman Historiography and Related Genres.Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholar Publishing. p. 146.ISBN978-1-4438-0015-0.

- ^abcdefghiJenkyns, Richard (2016).Classical Literature: An Epic Journey from Homer to Virgil and Beyond.New York City, New York: Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group.ISBN978-0-465-09797-5.

- ^Lattimore, Richmond (2011).The Iliad of Homer.The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London: The University of Chicago Press. Book 1, Line number 155 (p. 79).ISBN978-0-226-47049-8.

- ^Guy Hedreen, "The Cult of Achilles in the Euxine"Hesperia60.3 (July 1991), pp. 313–330.

- ^Stanford, William Bedell(1959) [1947]. "Introduction, Grammatical Introduction".Homer: Odyssey I-XII.Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Education. pp. ix–lxxxvi.ISBN1-85399-502-9.

- ^Harris, William."The Greek Dactylic Hexameter: A Practical Reading Approach".Middlebury College.Retrieved12 March2017.

- ^abM. Hadas (2013-08-13).A History of Greek Literature (p.16).published byColumbia University Press13 Aug 2013, 327 pages.ISBN978-0-231-51486-6.Retrieved2015-09-08.

- ^J.P. Barron andP.E. Easterling,"Hesiod" inThe Cambridge History of Classical Literature: Greek Literature,P. Easterling and B. Knox (eds), Cambridge University Press (1985), page 92

- ^West, M. L.Theogony.Oxford University Press (1966), page 40

- ^Jasper Griffin,"Greek Myth and Hesiod", J. Boardman, J. Griffin and O. Murray (eds),The Oxford History of the Classical World,Oxford University Press(1986), page 88

- ^Cartwright, Mark."Greek Religion".World History Encyclopedia.Retrieved17 January2017."... These traditions were first recounted only orally as there was no sacred text in Greek religion and later, attempts were made to put in writing this oral tradition, notably by Hesiod in hisTheogonyand more indirectly in the works of Homer.

- ^J. P. Barron and P. E. Easterling, 'Elegy and Iambus', inThe Cambridge History of Classical Literature: Greek Literature,P. Easterling and B. Knox (ed.s), Cambridge University Press (1985), page 117

- ^David A. Campbell,Greek Lyric Poetry,Bristol Classical Press (1982) page 136

- ^J. M. Edmonds -Lyra Graeca (p.3)Wildside Press LLC, 2007ISBN1-4344-9130-7[Retrieved 2015-05-06]

- ^Hallett, Judith P. (1979). "Sappho and her Social Context: Sense and Sensuality".Signs.4 (3).

- ^Rayor, Diane; Lardinois, André (2014).Sappho: A New Edition of the Complete Works.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-1-107-02359-8.

- ^Pausanias 3.15.2Ἀλκμᾶνι ποιήσαντι ἄισματα οὐδὲν ἐς ἡδονὴν αὐτῶν ἐλυμήνατο τῶν Λακῶνων ἡ γλῶσσα ἥκιστα παρεχομένη τὸ εὔφωνον.

- ^M. Davies's "Monody, Choral Lyric, and the Tyranny of the Hand-Book" inClassical Quarterly,NS 38 (1988), pp. 52–64.

- ^abcGarland, Robert (2008).Ancient Greece: Everyday Life in the Birthplace of Western Civilization.New York City, New York: Sterling. p. 284.ISBN978-1-4549-0908-8.

- ^Buckham, Philip Wentworth,Theatre of the Greeks,Cambridge: J. Smith, 1827.

- ^Garland, Robert (2008).Ancient Greece: Everyday Life in the Birthplace of Western Civilization.New York City, New York: Sterling. p. 290.ISBN978-1-4549-0908-8.

- ^Garland, Robert (2008).Ancient Greece: Everyday Life in the Birthplace of Western Civilization.New York City, New York: Sterling. pp. 284–296.ISBN978-1-4549-0908-8.

- ^Griffith, Mark.The Authenticity of the Prometheus Bound.Cambridge, 1977.

- ^Walton, J. Michael,Euripides Our Contemporary,University of California Press, 2009,ISBN0-520-26179-8.

- ^Burke, Kenneth (1952). "Form and Persecution in the Oresteia". The Sewanee Review. 60 (3: July – September): 377–396.JSTOR27538150.

- ^West, M.L. Studies in Aeschylus. Stuttgart, 1990.

- ^Suda (ed. Finkel et al.): s.v. Σοφοκλῆς.

- ^Fagles, Robert (1986).The Three Theban Plays.New York: Penguin. p. 35.

- ^Pomeroy, Sarah; Burstein, Stanley; Donlan, Walter; Roberts, Jennifer (1999).Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History.New York: Oxford University Press. p.322.ISBN0-19-509742-4.

- ^B. Knox, 'Euripides' in The Cambridge History of Classical Literature I: Greek Literature, P. Easterling and B. Knox (ed.s), Cambridge University Press (1985), page 316

- ^Walton (1997, viii, xix)

- ^B. Knox. "Euripides" inThe Cambridge History of Classical Literature I: Greek Literature,P. Easterling and B. Knox (ed.s), Cambridge University Press (1985), page 339

- ^Banham, Martin, ed. 1998.The Cambridge Guide to Theatre.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-43437-8.

- ^Brockett, Oscar G. and Franklin J. Hildy. 2003.History of the Theatre.Ninth edition, International edition. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.ISBN0-205-41050-2.

- ^Aristophanes: Clouds K.J. Dover (ed), Oxford University Press 1970, Intro. page X.

- ^David Barrett's editionAristophanes: the Frogs and Other Plays(Penguin Classics, 1964), p. 13

- ^Roche, Paul (2005).Aristophanes: The Complete Plays: A New Translation by Paul Roche.New York: New American Library. pp. x–xi.ISBN978-0-451-21409-6.

- ^Roche, Paul (2005).Aristophanes: The Complete Plays: A New Translation by Paul Roche.New York: New American Library. pp. 537–540.ISBN978-0-451-21409-6.

- ^Garland, Robert (2008).Ancient Greece: Everyday Life in the Birthplace of Western Civilization.New York City, New York: Sterling. p. 288.ISBN978-1-4549-0908-8.

- ^Hall, Edith; Wrigley, Amanda (2007).Aristophanes in Performance, 421 BC-AD 2007: Peace, Birds and Frogs.ISBN9781904350613.Retrieved5 April2011.

- ^Euripides. McHugh, Heather, trans.Cyclops; Greek Tragedy in New Translations.Oxford Univ. Press (2001)ISBN978-0-19-803265-6

- ^Hunt, A.S. (1912)The Oxyrhynchus Papyri: Part IX.London.

- ^T. James Luce,The Greek Historians,2002, p. 26.

- ^Procopius,John Moorhead,Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing: M–Z,Vol. II, Kelly Boyd, (Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1999), 962

- ^Xenophon,Hellenica7.5.27; Xenophon.Xenophontis opera omnia,vol. 1. Oxford, Clarendon Press. 1900, repr. 1968

- ^Danzig, Gabriel. 2003. "Apologizing for Socrates: Plato and Xenophon on Socrates' Behavior in Court." Transactions of the American Philological Association. Vol. 133, No. 2, pp. 281–321.

- ^G. S. Kirk and J. E. Raven and M. Schofield,The Presocratic Philosophers(Cambridge University Press, 1983, 108–109.

- ^Curd, Patricia,A Presocratics Reader: Selected Fragments and Testimonia(Hackett Publishing,1996), p. 12.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Smith, William,ed. (1870). "Pythagoras".Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.pp. 616–625.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Smith, William,ed. (1870). "Pythagoras".Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.pp. 616–625.

- ^Simon Trépanier, (2004),Empedocles: An Interpretation,Routledge.

- ^Kahn, Charles H.(1979).The Art and Thought of Heraclitus. An Edition of the Fragments with Translation and Commentary.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-21883-7.

- ^Berryman, Sylvia."Democritus".Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.Stanford University.Retrieved25 March2017.

- ^Kofman, Sarah (1998).Socrates: Fictions of a Philosopher.Cornell University Press. p. 34.ISBN0-8014-3551-X.

- ^Cohen, M.,Philosophical Tales: Being an Alternative History Revealing the Characters, the Plots, and the Hidden Scenes that Make Up the True Story of Philosophy,John Wiley & Sons, 2008, p. 5,ISBN1-4051-4037-2.

- ^Rubel, A.; Vickers, M. (11 September 2014).Fear and Loathing in Ancient Athens: Religion and Politics During the Peloponnesian War.Routledge. p.147.ISBN978-1-317-54480-7.

- ^Dorion, Louis-André (2010). "The Rise and Fall of the Socratic Problem".The Cambridge Companion to Socrates.Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–23.doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.001.hdl:10795/1977.ISBN978-0-521-83342-4.Retrieved2015-05-07.

- ^Henri Estienne(ed.),Platonis opera quae extant omnia,Vol. 1, 1578,p. 17.

- ^Lorenz, Hendrik (22 April 2009)."Ancient Theories of Soul".Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.Retrieved2013-12-10.

- ^Plato, The Symposium. Translation and introduction by Walter Hamilton. Penguin Classics. 1951.ISBN978-0-14-044024-9

- ^National Public Radio (August 8, 2007).Plato's 'Republic' Still Influential, Author Says.Talk of the Nation.

- ^Plato: The Republic.Plato: His Philosophy and his life, allphilosophers.com

- ^Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008).From Plato to Derrida.Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.ISBN978-0-13-158591-1.

- ^Magee, Bryan(2010).The Story of Philosophy.Dorling Kindersley. p. 34.

- ^Morison, William (2006)."The Lyceum".Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.Retrieved30 October2009.

- ^"Great Philosophers: Aristotle (384-322 BCE)".Great Philosophers.Oregon State University.Retrieved23 June2017.

- ^Bury, J. B. (1937).A History of Greece to the Death of Alexander the Great.New York: Modern Library. pp.668–723.

- ^Bury, J. B. (1937).A History of Greece to the Death of Alexander the Great.New York: Modern Library. pp.724–821.

- ^EntryΜουσείονatLiddell & Scott

- ^Phillips, Heather A. (August 2010)."The GreatLibraryof Alexandria? ".Library Philosophy and Practice.ISSN1522-0222.Archived fromthe originalon 2012-04-18.Retrieved2017-05-17.

- ^Introduction (p.14) to Virgil:The Ecloguestrans. Guy Lee (Penguin Classics)

- ^Article on "Bucolic poetry" inThe Oxford Companion to Classical Literature(1989)

- ^abcdefgHarder, Annette (2012).Callimachus: Aetia.Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–5.ISBN978-0-19-958101-6.

- ^Nisetich, Frank (2001).The Poems of Callimachus.Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. xviii–xx.ISBN0-19814760-0.Retrieved27 July2017.

- ^Blum 1991, p. 236, cited inPhillips, Heather A. (August 2010)."The GreatLibraryof Alexandria? ".Library Philosophy and Practice.ISSN1522-0222.Archived fromthe originalon 2012-04-18.Retrieved2017-05-17.

- ^Stephens, Susan (2011), "Ptolemaic Epic", in T. Papaghelis; A. Rengakos (eds.),Brill's Companion to Apollonius Rhodius; Second(Revised ed.), Brill

- ^A. W. Mair and G. R. Mair, trans., Callimachus and Lycophron; Aratus, Loeb Classical Library (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1921), p. 363

- ^Konstan, David (2010).Menander of Athens.Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–6.ISBN0-19-980519-9.

- ^Baron, Christopher A. (2013).Timaeus of Tauromenium and Hellenistic Historiography.Cambridge University Press.

- ^Brown, Truesdell S. (1958). Timaeus of Tauromenium. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^Marincola, John, ed.A companion to Greek and Roman historiography.John Wiley & Sons, 2010, 528-531.

- ^Bergmann, Uwe."X-Ray Fluorescence Imaging of the Archimedes Palimpsest: A Technical Summary"(PDF).Retrieved2013-09-29.

- ^Walsh, P.G. (1968). "Lucius Madaurensis".Phoenix.22(2): 143–157.doi:10.2307/1086837.JSTOR1086837.

- ^Apuleius Madaurensis, Lucius; trans. Lindsay, Jack (1960).The Golden Ass.Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p.31.ISBN0-253-20036-9.

- ^Edmund P. Cueva (Fall 1996). "Plutarch's Ariadne in Chariton's Chaereas and Callirhoe". American Journal of Philology. 117 (3): 473–484.doi:10.1353/ajp.1996.0045.

- ^Cf. Thomas Hägg, 'The Oriental Reception of Greek Novels: A Survey with Some Preliminary Considerations', Symbolae Osloenses, 61 (1986), 99–131 (p. 106),doi:10.1080/00397678608590800.

- ^Thomas Hägg and Bo Utas,The Virgin and Her Lover: Fragments of an Ancient Greek Novel and a Persian Epic Poem.Brill Studies in Middle Eastern Literatures, 30 (Leiden: Brill, 2003), p. 1.

- ^Reardon, Bryan P. (1989).Collected Ancient Greek Novels.Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 809–810.ISBN0-520-04306-5.Retrieved31 May2017.

- ^Metzger, Bruce M. (1987).The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance(PDF).Clarendon Press. pp. 295–296.ISBN0-19-826180-2.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2013-06-01.

- ^Trobisch, David (1994).Paul's Letter Collection: Tracing the Origins.Fortress Press. pp.1–27.ISBN0-8006-2597-8.

- ^Thomas Christian Tychsen,Quinti Smyrnaei Posthomericorum libri XIV. Nunc primum ad librorum manoscriptorum fidem et virorum doctorum coniecturas recensuit, restituit et supplevit Thom. Christ. Tychsen acceserunt observationes Chr. Gottl. Heynii(Strassburg: Typhographia Societatis Bipontinae) 1807.

- ^Armin H. Köchly,Quinti Smyrnaei Posthomericorum libri XIV. Recensuit, prolegomenis et adnotatione critica instruxit Arminius Koechly(Leipzig: Weidmannos) 1850.

- ^A.S. Way,Introduction1913.[full citation needed]

- ^Nikoletta Kanavou (2015), "Notes on the Blemyomachia (P. Berol. 5003 + P. Gen. inv. 140 + P. Phoib. fr. 1a/6a/11c/12c)",Tyche30:55–60.

- ^Vian, Francis. ' "Mârtus" chez Nonnos de Panopolis. Étude de sémantique et de chronologie.' REG 110, 1997, 143-60. Reprinted in: L'Épopée posthomérique. Recueil d'études. Ed. Domenico Accorinti. Alessandria: Edizioni dell'Orso, 2005 (Hellenica 17), 565-84

- ^Cameron, Alan, 2015.Wandering Poets and Other Essays on Late Greek Literature and Philosophy.Oxford University Press. p.81.

- ^Agathias Scholasticus,Hist.4.23. (530x580)

- ^Fornaro, S. s.v. Nonnus inBrill's New Paulyvol. 9 (ed. Canick & Schneider) (Leiden, 2006) col.812–815

- ^"Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 39, chapter 35".www.perseus.tufts.edu.Retrieved2016-11-02.

- ^Sacks, Kenneth S. (1990).Diodorus Siculus and the First Century.Princeton University Press.ISBN0-691-03600-4.

- ^T. Hidber.Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece(p.229). Routledge 31 Oct 2013, 832 pages,ISBN1-136-78799-2,(editor N. Wilson). Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ^White, Horace (1912). "Introduction".Appian's Roman History.Cambridge, Mass: The Loeb Classical Library. pp.vii–xii.ISBN0-674-99002-1.

- ^FW Walbank (November 1984). F. W. Walbank (ed.).The Cambridge Ancient History.Cambridge University Press, 6 Sep 1984.ISBN0-521-23445-X.Retrieved2015-04-01.

- ^"Plutarch".Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy.

- ^Stadter, Philip A. (2015).Plutarch and His Roman Readers.Oxford University Press. p. 69.ISBN978-0-19-871833-8.Retrieved 2015-02-04. Although Plutarch wrote in Greek and with a Greek point of view, [...] he was thinking of a Roman as well as a Greek audience.

- ^Ramsay, William (1867), "A. Gellius", in Smith, William,Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology,2, Boston, p. 235

- ^Ἀθήναιος [Athenaeus]. Δειπνοσοφισταί [Deipnosophistaí, Sophists at Dinner], c. 3rd century (Ancient Greek) Trans. Charles Burton Gulick as Athenaeus, Vol. I, p. viii. Harvard University Press (Cambridge), 1927. Accessed 13 Aug 2014.

- ^Aelian,Historical Miscellany.Translated by Nigel G. Wilson. 1997. Loeb Classical Library.ISBN978-0-674-99535-2

- ^Dueck, Daniela (2000).Strabo of Amasia: A Greek Man of Letters in Augustan Rome.London, New York: Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group. p. 145.ISBN0-415-21672-9.

- ^Historical and Ethnological Society of Greece, Aristéa Papanicolaou Christensen,The Panathenaic Stadium – Its History Over the Centuries(2003), p. 162

- ^Pausanias (18 October 2014).Description of Greece: Complete.First Rate Publishers.ISBN978-1-5028-8547-0.

- ^"Ptolemy | Accomplishments, Biography, & Facts".Encyclopædia Britannica.Retrieved2016-03-06.

- ^A. I. Sabra, "Configuring the Universe: Aporetic, Problem Solving, and Kinematic Modeling as Themes of Arabic Astronomy,"Perspectives on Science6.3 (1998): 288–330, at pp. 317–18

- ^NT Hamilton, N. M. Swerdlow,G. J. Toomer."The Canobic Inscription: Ptolemy's Earliest Work". In Berggren and Goldstein, eds.,From Ancient Omens to Statistical Mechanics.Copenhagen: University Library, 1987.

- ^Fraser, Craig G. (2006).The Cosmos: A Historical Perspective.p. 14.

- ^Lattis, James L. (1995).Between Copernicus and Galileo: Christoph Clavius and the Collapse of Ptolemaic Cosmology,University of Chicago Press, pgs 186–190

- ^Epictetus,Discourses,prologue.

- ^Long, Herbert S. (1972). Introduction.Lives of Eminent Philosophers.By Laërtius, Diogenes. Vol. 1 (reprint ed.). Loeb Classical Library. p. xvi.

- ^"Diogenes Laërtius",The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia,2013

- ^

Laërtius, Diogenes(1925c)..Lives of the Eminent Philosophers.Vol. 2:10. Translated byHicks, Robert Drew(Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes(1925c)..Lives of the Eminent Philosophers.Vol. 2:10. Translated byHicks, Robert Drew(Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

- ^Philip Merlan,From Platonism to Neoplatonism(The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1954, 1968), p. 3.

- ^Detlef Thiel:Die Philosophie des Xenokrates im Kontext der Alten Akademie,München 2006, pp. 197ff. and note 64; Jens Halfwassen:Der Aufstieg zum Einen.

- ^"Who was Plotinus?".Australian Broadcasting Corporation.11 June 2011.

- ^New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge 3rd ed. 1914.Pg 284

- ^Moore, Edward."Origen of Alexandria (entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)".The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.IEP.ISSN2161-0002.Retrieved2014-04-27.

- ^Schaff, Philip (1910).The new Schaff-Herzog encyclopedia of religious knowledge: embracing biblical, historical, doctrinal, and practical theology and biblical, theological, and ecclesiastical biography from the earliest times to the present day.Funk and Wagnalls Company. p.272.Retrieved2014-07-30.

- ^Herzog, Johann Jakob; Philip Schaff; Albert Hauck (December 1908). "Celsus". In Samual Macauley Jackson (ed.).The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge.Vol. II. New York and London: Funk and Wagnalls Company. p. 466.

- ^The "early dating of P.Oxy 3836 holds, Achilles Tatius' novel must have been written 'nearer 120 than 150'" Albert Henrichs, Culture In Pieces: Essays on Ancient Texts in Honour of Peter Parsons, eds. Dirk Obbink, Richard Rutherford, Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 309, n. 29ISBN0-19-929201-9,9780199292011

- ^"the use (albeit mid and erratic) of the Attic dialect suggest a date a little earlier [than mid-2nd century] in the same century." The Greek Novel: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 7ISBN0-19-980303-X,9780199803033

- ^abLongus; Xenophon of Ephesus (2009), Henderson, Jeffery, ed., Anthia and Habrocomes (translation), Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, pp. 69 & 127,ISBN978-0-674-99633-5

- ^Richard Hunter(1996). "Longus,Daphnis and Chloe".In Gareth L. Schmeling (ed.).The Novel in the Ancient World.Brill. pp. 361–86.ISBN90-04-09630-2.

- ^J.R. Morgan. Lucian's True Histories and the Wonders Beyond Thule of Antonius Diogenes. The Classical Quarterly (New Series), 35, pp 475–490doi:10.1017/S0009838800040313.

- ^Moeser, Marion (Dec 15, 2002). The Anecdote in Mark, the Classical World and the Rabbis: A Study of Brief Stories in the Demonax, The Mishnah, and Mark 8:27–10:45. A&C Black. p. 88.ISBN978-0-8264-6059-2.Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^Lightfoot,De Dea Syria(2003)

- ^Lucinda Dirven, "The Author of De Dea Syria and his Cultural Heritage", Numen 44.2 (May 1997), pp. 153–179.

- ^Greg Grewell: "Colonizing the Universe: Science Fictions Then, Now, and in the (Imagined) Future", Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature, Vol. 55, No. 2 (2001), pp. 25–47 (30f.)

- ^Fredericks, S.C.: "Lucian's True History as SF", Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (March 1976), pp. 49–60

- ^"The Doubter" by Lucian in Roger Lancelyn Green (1970)Thirteen Uncanny Tales.London, Dent: 14–21; and Finucane, pg 26.

- ^George Luck "Witches and Sorcerers in Classical Literature", p. 141,Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: Ancient Greece And Romeedited by Bengt Ankarloo and Stuart ClarkISBN0-8122-1705-5

- ^Robert E. Van Voorst,Jesus outside the New Testament,Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000.

- ^Holzberg, Niklas. The Ancient Novel. 1995. p. 78

- ^Bowersock, Glanwill W. The Aethiopica of Heliodorus and the Historia Augusta. In: Historiae Augustae Colloquia n.s. 2, Colloquium Genevense 1991. p. 43.

- ^abReardon, Bryan P. (1989).Collected Ancient Greek Novels.Berkeley: University of California Press.ISBN0-520-04306-5.Retrieved22 June2017.

- ^ab"Western literature".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Retrieved19 June2017.

- ^English translations of Musaeus Grammaticus'Hero and Leander: The Divine Poem of Musaeus: First of All Books Translated According to the Original(George Chapman, 1616); Hero & Leander (E.E. Sikes, 1920)

- ^Jenkyns, Richard (2007).Classical Epic: Homer and Virgil.London: Duckworth. p. 53.ISBN978-1-85399-133-2.

- ^Sandys, Sir John Edwin (1921).A History of Classical Scholarship; Volume One: From the Sixth Century B.C. to the End of the Middle Ages(3 ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 591.ISBN978-1-108-02706-9.Retrieved24 March2017.

- ^Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society,Marvin Perry, Myrna Chase, Margaret C. Jacob, James R. Jacob, 2008, 903 pages, p.261/262.

- ^Reynolds and Wilson, pp. 119, 131.

- ^W. W. Combs,Erasmus and the textus receptus,DBSJ 1 (Spring 1996), 45.

- ^Meagher, Robert E. (2002).The Meaning of Helen: In Search of an Ancient Icon.Wauconda, Illinois: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. p.56.ISBN0-86516-510-6.Retrieved19 June2017.

- ^Osborn, Kevin; Burgess, Dana (1998-07-01).The Complete Idiot's Guide to Classical Mythology.Penguin. pp. 270–.ISBN9780028623856.Retrieved19 December2012.

- ^abcdGrafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore (2010).The Classical Tradition.Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.ISBN978-0-674-03572-0.

- ^Armstrong, A. Macc. "Timon of Athens - A Legendary Figure?",Greece & Rome,2nd Ser., Vol. 34, No. 1 (April 1987), pp. 7–11

- ^Reardon, Bryan P. (1989).Collected Ancient Greek Novels.Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 737.ISBN0-520-04306-5.Retrieved17 June2017.

- ^Kirk, G. S. (1976).Homer and the Oral Tradition.Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp.85–99.ISBN978-0-521-13671-6.

Homeric style.

- ^Osgood, Charles Grosvenor (1900).The Classical Mythology of Milton's English Poems.New York City, New York: Henry Holt. p. ix-xi.Retrieved5 June2017.

- ^Richard, Carl J.,The Golden Age of the Classics in America,Harvard University Press, 2009, page 33.

- ^Harte, Tim (Summer 2003)."Sarah Danius, The Senses of Modernism: Technology, Perception, and Aesthetics".Bryn Mawr Review of Comparative Literature.4(1). Archived fromthe originalon 2003-11-05.Retrieved2001-07-10.(review of Danius book).

- ^Kiberd, Declan (16 June 2009)."Ulysses, Modernism's Most Sociable Masterpiece".The Guardian.London.Retrieved28 June2011.

- ^Jaurretche, Colleen (2005).Beckett, Joyce and the Art of the Negative.European Joyce studies. Vol. 16. Rodopi. p. 29.ISBN978-90-420-1617-0.RetrievedFebruary 1,2011.

- ^Ellmann, Richard.James Joyce.Oxford University Press, revised edition (1983).

- ^"Who was Mary Renault?".The Mary Renault Society.Retrieved31 May2017.

- ^Forster, E. M.; Hans-Georg, Gadamer."Aristotle:Poetics".CriticaLink.University of Hawaii.Retrieved25 June2017.

- ^Habib, M.A.R. (2005).A History of Literary Criticism and Theory: From Plato to the Present.Wiley-Blackwell.p.60.ISBN0-631-23200-1.

- ^"Catharsis".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Retrieved25 June2017.

- ^"Ethos".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Retrieved25 June2017.

- ^"Anagnorisis".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Retrieved25 June2017.

- ^"Hamartia".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Retrieved25 June2017.

- ^"Hubris".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Retrieved25 June2017.

- ^"Mimesis".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Retrieved25 June2017.

- ^"Plot".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Retrieved25 June2017.

- ^"Nemesis".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Retrieved25 June2017.

- ^"Peripeteia".Encyclopaedia Britannica.Retrieved25 June2017.

Further reading[edit]

- Beye, Charles Rowan (1987).Ancient Greek Literature and Society.Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.ISBN0-8014-1874-7.

- Easterling, P.E.; Knox, B.M.W., eds. (1985).The Cambridge History of Classical Literature: Volume 1: Greek literature.Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]; New York: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-21042-9.

- Flacelière, Robert(1964).A Literary History of Greece.(Translated by Douglas Garman). Chicago: Aldine Pub.

- Gutzwiller, Kathryn (2007).A Guide to Hellenistic Literature.Blackwell.ISBN978-0-631-23322-0.

- Hadas, Moses(1950).A History of Greek Literature.New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Lesky, Albin (1966).A History of Greek Literature.Translated by James Willis; Cornelis de Heer. Indianapolis / Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company.ISBN0-87220-350-6.

- Schmidt, Michael (2004).The First Poets: Lives of the Ancient Greek Poets.London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.ISBN0-297-64394-0.

- C. A. Trypanis(1981).Greek Poetry from Homer to Seferis.University of Chicago Press.ISBN9780226813165.

- Whitmarsh, Tim (2004).Ancient Greek Literature.Cambridge: Polity Press.ISBN0-7456-2792-7.

- Walton, J. Michael (2006).Found in Translation: Greek Drama in English.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-86110-6.Retrieved24 December2023.

External links[edit]

Works related toAncient Greek literatureat Wikisource

Works related toAncient Greek literatureat Wikisource