Liberalism

| Part ofa serieson |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

| Part of thePolitics series |

| Party politics |

|---|

|

|

Liberalismis apoliticalandmoral philosophybased on therights of the individual,liberty,consent of the governed,political equality,right to private propertyandequality before the law.[1][2]Liberals espouse various and often mutually warring views depending on their understanding of these principles but generally supportprivate property,market economies,individual rights (includingcivil rightsandhuman rights),liberal democracy,secularism,rule of law,economicandpolitical freedom,freedom of speech,freedom of the press,freedom of assembly,andfreedom of religion.[3]Liberalism is frequently cited as the dominantideologyofmodern history.[4][5]: 11

Liberalism became a distinctmovementin theAge of Enlightenment,gaining popularity amongWesternphilosophers andeconomists.Liberalism sought to replace thenormsofhereditary privilege,state religion,absolute monarchy,thedivine right of kingsandtraditional conservatismwithrepresentative democracy,rule of law, and equality under the law. Liberals also endedmercantilistpolicies,royal monopolies,and othertrade barriers,instead promoting free trade and marketization.[6]PhilosopherJohn Lockeis often credited with founding liberalism as a distinct tradition based on thesocial contract,arguing that each man has anatural righttolife, liberty and property,and governments must not violate theserights.[7]While theBritish liberal traditionhas emphasized expanding democracy,French liberalismhas emphasized rejectingauthoritarianismand is linked tonation-building.[8]

Leaders in the BritishGlorious Revolutionof 1688,[9]theAmerican Revolutionof 1776, and theFrench Revolutionof 1789 used liberal philosophy to justify the armed overthrow of royalsovereignty.The 19th century saw liberal governments established inEuropeandSouth America,and it was well-established alongsiderepublicanism in the United States.[10]InVictorian Britain,it was used to critique the political establishment, appealing to science and reason on behalf of the people.[11]During the 19th and early 20th centuries,liberalism in the Ottoman Empireand theMiddle Eastinfluenced periods of reform, such as theTanzimatandAl-Nahda,and the rise ofconstitutionalism,nationalism,andsecularism.These changes, along with other factors, helped to create a sense of crisis withinIslam,which continues to this day, leading toIslamic revivalism.Before 1920, the main ideological opponents of liberalism werecommunism,conservatism,andsocialism;[12]liberalism then faced major ideological challenges fromfascismandMarxism–Leninismas new opponents. During the 20th century, liberal ideas spread even further, especially in Western Europe, as liberal democracies found themselves as the winners in bothworld wars[13]and theCold War.[14][15]

Liberals sought and established a constitutional order that prized importantindividual freedoms,such asfreedom of speechandfreedom of association;anindependent judiciaryand publictrial by jury;and the abolition ofaristocraticprivileges.[6]Later waves of modern liberal thought and struggle were strongly influenced by the need to expand civil rights.[16]Liberals have advocated gender and racial equality in their drive to promote civil rights, and globalcivil rights movementsin the 20th century achieved several objectives towards both goals. Other goals often accepted by liberals includeuniversal suffrageanduniversal access to education.In Europe and North America, the establishment ofsocial liberalism(often called simplyliberalismin the United States) became a key component in expanding thewelfare state.[17]Today,liberal partiescontinue to wield power and influencethroughout the world.The fundamental elements ofcontemporary societyhave liberal roots. The early waves of liberalism popularised economic individualism while expanding constitutional government andparliamentaryauthority.[6]

Etymology and definition

| Part ofa serieson |

| Libertarianism |

|---|

Liberal,liberty,libertarian,andlibertineall trace theiretymologytoliber,arootfromLatinthat means "free".[18]One of the first recorded instances ofliberaloccurred in 1375 when it was used to describe theliberal artsin the context of an education desirable for a free-born man.[18]The word's early connection with the classical education of a medieval university soon gave way to a proliferation of different denotations and connotations.Liberalcould refer to "free in bestowing" as early as 1387, "made without stint" in 1433, "freely permitted" in 1530, and "free from restraint" —often as a pejorative remark—in the 16th and the 17th centuries.[18]

In the 16th-centuryKingdom of England,liberalcould have positive or negative attributes in referring to someone's generosity or indiscretion.[18]InMuch Ado About Nothing,William Shakespearewrote of "a liberal villaine" who "hath... confest his vile encounters".[18]With the rise ofthe Enlightenment,the word acquired decisively more positive undertones, defined as "free from narrow prejudice" in 1781 and "free from bigotry" in 1823.[18]In 1815, the first use ofliberalismappeared in English.[19]In Spain, theliberales,the first group to use the liberal label in a political context,[20]fought for decades to implement theSpanish Constitution of 1812.From 1820 to 1823, during theTrienio Liberal,King Ferdinand VIIwas compelled by theliberalesto swear to uphold the 1812 Constitution. By the middle of the 19th century,liberalwas used as a politicised term for parties and movements worldwide.[21]

Over time, the meaning ofliberalismbegan to diverge in different parts of the world. According to theEncyclopædia Britannica:"In the United States, liberalism is associated with the welfare-state policies of the New Deal programme of the Democratic administration of Pres.Franklin D. Roosevelt,whereas in Europe it is more commonly associated with a commitment tolimited governmentandlaissez-faireeconomic policies. "[22]Consequently, the ideas ofindividualismandlaissez-faireeconomics previously associated withclassical liberalismare key components of modernAmerican conservatismandmovement conservatism,and became the basis for the emerging school of modernAmerican libertarianthought.[23][better source needed]In this American context,liberalis often used as a pejorative.[24]

Yellowis thepolitical colourmost commonly associated with liberalism.[25][26][27]In Europe and Latin America,liberalismmeans a moderate form ofclassical liberalismand includes bothconservative liberalism(centre-rightliberalism) andsocial liberalism(centre-leftliberalism).[28]In North America,liberalismalmost exclusively refers to social liberalism. The dominant Canadian party is theLiberal Party,and theDemocratic Partyis usually considered liberal in the United States.[29][30][31]In the United States, conservative liberals are usually calledconservativesin a broad sense.[32][33]

Philosophy

Liberalism—both as a political current and an intellectual tradition—is mostly a modern phenomenon that started in the 17th century, although some liberal philosophical ideas had precursors inclassical antiquityandImperial China.[34][35]TheRoman EmperorMarcus Aureliuspraised "the idea of a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed".[36]Scholars have also recognised many principles familiar to contemporary liberals in the works of severalSophistsand theFuneral OrationbyPericles.[37]Liberal philosophy is the culmination of an extensive intellectual tradition that has examined and popularized some of the modern world's most important and controversial principles. Its immense scholarly output has been characterized as containing "richness and diversity", but that diversity often has meant that liberalism comes in different formulations and presents a challenge to anyone looking for a clear definition.[38]

Major themes

| Part of a series on |

| Individualism |

|---|

Although all liberal doctrines possess a common heritage, scholars frequently assume that those doctrines contain "separate and often contradictory streams of thought".[38]The objectives ofliberal theorists and philosophershave differed across various times, cultures and continents. The diversity of liberalism can be gleaned from the numerous qualifiers that liberal thinkers and movements have attached to the term "liberalism", includingclassical,egalitarian,economic,social,thewelfare state,ethical,humanist,deontological,perfectionist,democratic,andinstitutional,to name a few.[39]Despite these variations, liberal thought does exhibit a few definite and fundamental conceptions.

Political philosopherJohn Grayidentified the common strands in liberal thought asindividualist,egalitarian,melioristanduniversalist.The individualist element avers the ethical primacy of the human being against the pressures of socialcollectivism;the egalitarian element assigns the samemoralworth and status to all individuals; the meliorist element asserts that successive generations can improve their sociopolitical arrangements, and the universalist element affirms the moral unity of the human species and marginalises localculturaldifferences.[40]The meliorist element has been the subject of much controversy, defended by thinkers such asImmanuel Kant,who believed in human progress, while suffering criticism by thinkers such asJean-Jacques Rousseau,who instead believed that human attempts to improve themselves through socialcooperationwould fail.[41]

The liberal philosophical tradition has searched for validation and justification through several intellectual projects. The moral and political suppositions of liberalism have been based on traditions such as natural rights andutilitarian theory,although sometimes liberals even request support from scientific and religious circles.[40]Through all these strands and traditions, scholars have identified the following major common facets of liberal thought:

- believing in equality andindividual liberty

- supporting private property and individual rights

- supporting the idea of limited constitutional government

- recognising the importance of related values such aspluralism,toleration,autonomy,bodily integrity,andconsent[42]

Classical and modern

John Locke and Thomas Hobbes

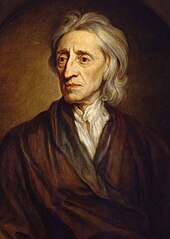

Enlightenmentphilosophers are given credit for shaping liberal ideas. These ideas were first drawn together and systematized as a distinctideologyby the English philosopherJohn Locke,generally regarded as the father of modern liberalism.[43][44]Thomas Hobbesattempted to determine the purpose and the justification of governing authority in post-civil war England. Employing the idea of astate of nature— a hypothetical war-like scenario prior to the state — he constructed the idea of asocial contractthat individuals enter into to guarantee their security and, in so doing, form the State, concluding that only anabsolute sovereignwould be fully able to sustain such security. Hobbes had developed the concept of the social contract, according to which individuals in the anarchic and brutal state of nature came together and voluntarily ceded some of their rights to an established state authority, which would create laws to regulate social interactions to mitigate or mediate conflicts and enforce justice. Whereas Hobbes advocated a strong monarchical commonwealth (theLeviathan), Locke developed the then-radical notion that government acquiresconsent from the governed,which has to be constantly present for the government to remainlegitimate.[45]While adopting Hobbes's idea of a state of nature and social contract, Locke nevertheless argued that when the monarch becomes atyrant,it violates the social contract, which protects life, liberty and property as a natural right. He concluded that the people have a right to overthrow a tyrant. By placing the security of life, liberty and property as the supreme value of law and authority, Locke formulated the basis of liberalism based on social contract theory. To these early enlightenment thinkers, securing the essential amenities of life—libertyandprivate property—required forming a "sovereign" authority with universal jurisdiction.[46]

His influentialTwo Treatises(1690), the foundational text of liberal ideology, outlined his major ideas. Once humans moved out of theirnatural stateand formedsocieties,Locke argued, "that which begins and actually constitutes anypolitical societyis nothing but the consent of any number of freemen capable of a majority to unite and incorporate into such a society. And this is that, and that only, which did or could give beginning to any lawful government in the world ".[47]: 170 The stringent insistence that lawful government did not have asupernaturalbasis was a sharp break with the dominant theories of governance, which advocated the divine right of kings[48]and echoed the earlier thought ofAristotle.Dr John Zvesper described this new thinking: "In the liberal understanding, there are no citizens within the regime who can claim to rule by natural or supernatural right, without the consent of the governed".[49]

Locke had other intellectual opponents besides Hobbes. In theFirst Treatise,Locke aimed his arguments first and foremost at one of the doyens of 17th-century English conservative philosophy:Robert Filmer.Filmer'sPatriarcha(1680) argued for thedivine right of kingsby appealing tobiblicalteaching, claiming that the authority granted toAdambyGodgave successors of Adam in the male line of descent a right of dominion over all other humans and creatures in the world.[50]However, Locke disagreed so thoroughly and obsessively with Filmer that theFirst Treatiseis almost a sentence-by-sentence refutation ofPatriarcha.Reinforcing his respect for consensus, Locke argued that "conjugal society is made up by a voluntary compact between men and women".[51]Locke maintained that the grant of dominion inGenesiswas not tomen over women,as Filmer believed, but to humans over animals.[51]Locke was not afeministby modern standards, but the first major liberal thinker in history accomplished an equally major task on the road to making the world more pluralistic: integrating women intosocial theory.[51]

Locke also originated the concept of theseparation of church and state.[52]Based on the social contract principle, Locke argued that the government lacked authority in the realm of individualconscience,as this was somethingrationalpeople could not cede to the government for it or others to control. For Locke, this created a natural right to the liberty of conscience, which he argued must remain protected from any government authority.[53]In hisLetters Concerning Toleration,he also formulated a general defence forreligious toleration.Three arguments are central:

- Earthly judges, the state in particular, and human beings generally, cannot dependably evaluate the truth claims of competing religious standpoints;

- Even if they could, enforcing a single "true religion"would not have the desired effect because belief cannot be compelled byviolence;

- Coercingreligious uniformitywould lead to more social disorder than allowing diversity.[54]

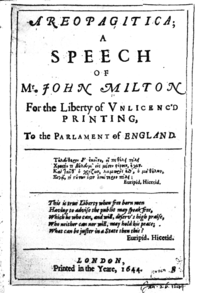

Locke was also influenced by the liberal ideas of Presbyterian politician and poetJohn Milton,who was a staunch advocate of freedom in all its forms.[55]Milton argued fordisestablishmentas the only effective way of achieving broadtoleration.Rather than force a man's conscience, the government should recognise the persuasive force of the gospel.[56]As assistant toOliver Cromwell,Milton also drafted a constitution of theindependents(Agreement of the People;1647) that strongly stressed the equality of all humans as a consequence of democratic tendencies.[57]In hisAreopagitica,Milton provided one of the first arguments for the importance of freedom of speech— "the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties". His central argument was that the individual could use reason to distinguish right from wrong. To exercise this right, everyone must have unlimited access to the ideas of his fellow men in "a free and open encounter",which will allow good arguments to prevail.

In a natural state of affairs, liberals argued, humans were driven by the instincts of survival andself-preservation,and the only way to escape from such a dangerous existence was to form a common and supreme power capable of arbitrating between competing human desires.[58]This power could be formed in the framework of acivil societythat allows individuals to make a voluntary social contract with the sovereign authority, transferring their natural rights to that authority in return for the protection of life, liberty and property.[58]These early liberals often disagreed about the most appropriate form of government, but all believed that liberty was natural and its restriction needed strong justification.[58]Liberals generally believed in limited government, although several liberal philosophers decried government outright, withThomas Painewriting, "government even in its best state is a necessary evil".[59]

James Madison and Montesquieu

As part of the project to limit the powers of government, liberal theorists such asJames MadisonandMontesquieuconceived the notion ofseparation of powers,a system designed to equally distribute governmental authority among theexecutive,legislativeandjudicialbranches.[59]Governments had to realise, liberals maintained, that legitimate government only exists with theconsent of the governed,so poor and improper governance gave the people the authority to overthrow the ruling order through all possible means, even through outright violence andrevolution,if needed.[60]Contemporary liberals, heavily influenced by social liberalism, have supported limitedconstitutional governmentwhile advocating forstate servicesand provisions to ensure equal rights. Modern liberals claim that formal or official guarantees of individual rights are irrelevant when individuals lack the material means to benefit from those rights and call for agreater role for governmentin the administration of economic affairs.[61]Early liberals also laid the groundwork for the separation of church and state. As heirs of the Enlightenment, liberals believed that any given social and political order emanatedfrom human interactions,not fromdivine will.[62]Many liberals were openly hostile toreligious beliefbut most concentrated their opposition to the union of religious and political authority, arguing that faith could prosper independently without official sponsorship or administration by the state.[62]

Beyond identifying a clear role for government in modern society, liberals have also argued over the meaning and nature of the most important principle in liberal philosophy: liberty. From the 17th century until the 19th century, liberals (fromAdam SmithtoJohn Stuart Mill) conceptualised liberty as the absence of interference from government and other individuals, claiming that all people should have the freedom to develop their unique abilities and capacities without being sabotaged by others.[63]Mill'sOn Liberty(1859), one of the classic texts in liberal philosophy, proclaimed, "the only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way".[63]Support forlaissez-fairecapitalismis often associated with this principle, withFriedrich Hayekarguing inThe Road to Serfdom(1944) that reliance on free markets would preclude totalitarian control by the state.[64]

Coppet Group and Benjamin Constant

The development into maturity of modern classical in contrast to ancient liberalism took place before and soon after the French Revolution. One of the historic centres of this development was atCoppet CastlenearGeneva,where the eponymousCoppet groupgathered under the aegis of the exiled writer andsalonnière,Madame de Staël,in the period between the establishment ofNapoleon's First Empire (1804) and theBourbon Restorationof 1814–1815.[65][66][67][68]The unprecedented concentration of European thinkers who met there was to have a considerable influence on the development of nineteenth-century liberalism and, incidentally,romanticism.[69][70][71]They includedWilhelm von Humboldt,Jean de Sismondi,Charles Victor de Bonstetten,Prosper de Barante,Henry Brougham,Lord Byron,Alphonse de Lamartine,SirJames Mackintosh,Juliette RécamierandAugust Wilhelm Schlegel.[72]

Among them was also one of the first thinkers to go by the name of "liberal", theEdinburgh University-educated Swiss Protestant,Benjamin Constant,who looked to the United Kingdom rather than toancient Romefor a practical model of freedom in a large mercantile society. He distinguished between the "Liberty of the Ancients" and the "Liberty of the Moderns".[73]The Liberty of the Ancients was a participatoryrepublicanliberty,[74]which gave the citizens the right to influence politics directly through debates and votes in the public assembly.[73]In order to support this degree of participation, citizenship was a burdensome moral obligation requiring a considerable investment of time and energy. Generally, this required a sub-group of slaves to do much of the productive work, leaving citizens free to deliberate on public affairs. Ancient Liberty was also limited to relatively small and homogenous male societies, where they could congregate in one place to transact public affairs.[73]

In contrast, the Liberty of the Moderns was based on the possession ofcivil liberties,the rule of law, and freedom from excessive state interference. Direct participation would be limited: a necessary consequence of the size of modern states and the inevitable result of creating a mercantile society where there were no slaves, but almost everybody had to earn a living through work. Instead, the voters would electrepresentativeswho would deliberate in Parliament on the people's behalf and would save citizens from daily political involvement.[73]The importance of Constant's writings on the liberty of the ancients and that of the "moderns" has informed the understanding of liberalism, as has his critique of the French Revolution.[75]The British philosopher and historian of ideas, SirIsaiah Berlin,has pointed to the debt owed to Constant.[76]

British liberalism

Liberalism in Britainwas based on core concepts such asclassical economics,free trade,laissez-fairegovernment with minimal intervention and taxation and abalanced budget.Classical liberals were committed to individualism, liberty and equal rights. Writers such asJohn BrightandRichard Cobdenopposed aristocratic privilege and property, which they saw as an impediment to developing a class ofyeomanfarmers.[77]

Beginning in the late 19th century, a new conception of liberty entered the liberal intellectual arena. This new kind of liberty became known aspositive libertyto distinguish it from the priornegative version,and it was first developed byBritish philosopherT. H. Green.Green rejected the idea that humans were driven solely byself-interest,emphasising instead the complex circumstances involved in the evolution of ourmoral character.[78]: 54–55 In a very profound step for the future of modern liberalism, he also tasked society and political institutions with the enhancement of individual freedom and identity and the development of moral character, will and reason and the state to create the conditions that allow for the above, allowing genuinechoice.[78]: 54–55 Foreshadowing the new liberty as the freedom to act rather than to avoid suffering from the acts of others, Green wrote the following:

If it were ever reasonable to wish that the usage of words had been other than it has been... one might be inclined to wish that the term 'freedom' had been confined to the... power to do what one wills.[79]

Rather than previous liberal conceptions viewing society as populated by selfish individuals, Green viewed society as an organic whole in which all individuals have adutyto promote thecommon good.[78]: 55 His ideas spread rapidly and were developed by other thinkers such asLeonard Trelawny HobhouseandJohn A. Hobson.In a few years, thisNew Liberalismhad become the essential social and political programme of the Liberal Party in Britain,[78]: 58 and it would encircle much of the world in the 20th century. In addition to examining negative and positive liberty, liberals have tried to understand the proper relationship between liberty and democracy. As they struggled to expandsuffrage rights,liberals increasingly understood that people left out of thedemocratic decision-making processwere liable to the "tyranny of the majority",a concept explained in Mill'sOn LibertyandDemocracy in America(1835) byAlexis de Tocqueville.[80]As a response, liberals began demanding proper safeguards to thwart majorities in their attempts at suppressing therights of minorities.[80]

Besides liberty, liberals have developed several other principles important to the construction of their philosophical structure, such as equality, pluralism and tolerance. Highlighting the confusion over the first principle,Voltairecommented, "equality is at once the most natural and at times the most chimeral of things".[81]All forms of liberalism assume in some basic sense that individuals are equal.[82]In maintaining that people are naturally equal, liberals assume they all possess the same right to liberty.[83]In other words, no one is inherently entitled to enjoy the benefits of liberal society more than anyone else, and all people areequal subjects before the law.[84]Beyond this basic conception, liberal theorists diverge in their understanding of equality. American philosopherJohn Rawlsemphasised the need to ensure equality under the law and the equal distribution of material resources that individuals required to develop theiraspirationsin life.[84]Libertarian thinkerRobert Nozickdisagreed with Rawls, championing the former version ofLockean equality.[84]

To contribute to the development of liberty, liberals also have promoted concepts like pluralism and tolerance. By pluralism, liberals refer to the proliferation of opinions and beliefs that characterise a stablesocial order.[85]Unlike many of their competitors and predecessors, liberals do not seek conformity and homogeneity in how people think. Their efforts have been geared towards establishing a governing framework thatharmonises and minimises conflicting viewsbut still allows those views to exist and flourish.[86]For liberal philosophy, pluralism leads easily to toleration. Since individuals will hold diverging viewpoints, liberals argue, they ought to uphold and respect the right of one another to disagree.[87]From the liberal perspective, toleration was initially connected toreligious toleration,withBaruch Spinozacondemning "the stupidity of religious persecution and ideological wars".[87]Toleration also played a central role in theideas of Kantand John Stuart Mill. Both thinkers believed that society would contain different conceptions of a good ethical life and that people should be allowed to make their own choices without interference from the state or other individuals.[87]

Liberal economic theory

Adam Smith'sThe Wealth of Nations,published in 1776, followed by the French liberal economistJean-Baptiste Say's treatise onPolitical Economypublished in 1803 and expanded in 1830 with practical applications, were to provide most of the ideas of economics until the publication ofJohn Stuart Mill'sPrinciplesin 1848.[88]: 63, 68 Smith addressed the motivation for economic activity, the causes ofpricesandwealth distribution,and thepoliciesthe state should follow to maximisewealth.[88]: 64

Smith wrote that as long assupply, demand,pricesandcompetitionwere left free of government regulation, the pursuit of material self-interest, rather than altruism, maximises society's wealth[89]through profit-driven production of goods and services. An "invisible hand"directed individuals and firms to work toward the nation's good as an unintended consequence of efforts to maximise their gain. This provided a moral justification for accumulating wealth, which some had previously viewed as sinful.[88]: 64

Smith assumed that workers could bepaidas low as was necessary for their survival, whichDavid RicardoandThomas Robert Malthuslater transformed into the "iron law of wages".[88]: 65 His main emphasis was on the benefit of free internal andinternational trade,which he thought could increase wealth through specialisation in production.[88]: 66 He also opposed restrictivetrade preferences,state grants ofmonopoliesandemployers' organisationsandtrade unions.[88]: 67 Government should be limited to defence,public worksand theadministration of justice,financed bytaxes based on income.[88]: 68 Smith was one of the progenitors of the idea, which was long central to classical liberalism and has resurfaced in theglobalisationliterature of the later 20th and early 21st centuries, that free trade promotes peace.[90]Smith's economics was carried into practice in the 19th century with the lowering of tariffs in the 1820s, the repeal of thePoor Relief Actthat had restricted the mobility of labour in 1834 and the end of the rule of theEast India Companyover India in 1858.[88]: 69

In hisTreatise(Traité d'économie politique), Say states that any production process requires effort, knowledge and the "application" of the entrepreneur. He sees entrepreneurs as intermediaries in the production process who combine productive factors such as land, capital and labour to meet the consumers' demands. As a result, they play a central role in the economy through their coordinating function. He also highlights qualities essential for successful entrepreneurship and focuses on judgement, in that they have continued to assess market needs and the means to meet them. This requires an "unerring market sense". Say views entrepreneurial income primarily as the high revenue paid in compensation for their skills and expert knowledge. He does so by contrasting the enterprise and supply-of-capital functions, distinguishing the entrepreneur's earnings on the one hand and the remuneration of capital on the other. This differentiates his theory from that ofJoseph Schumpeter,who describes entrepreneurial rent as short-term profits which compensate for high risk (Schumpeterian rent). Say himself also refers to risk and uncertainty along with innovation without analysing them in detail.

Say is also credited withSay's law,or the law of markets which may be summarised as "Aggregate supplycreates its ownaggregate demand", and"Supply creates its own demand",or" Supply constitutes its own demand "and" Inherent in supply is the need for its own consumption ". The related phrase" supply creates its own demand "was coined byJohn Maynard Keynes,who criticized Say's separate formulations as amounting to the same thing. Some advocates of Say's law who disagree with Keynes have claimed that Say's law can be summarized more accurately as "production precedes consumption" and that what Say is stating is that for consumption to happen, one must produce something of value so that it can be traded for money or barter for consumption later.[91][92] Say argues, "products are paid for with products" (1803, p. 153) or "a glut occurs only when too much resource is applied to making one product and not enough to another" (1803, pp. 178–179).[93]

Related reasoning appears in the work ofJohn Stuart Milland earlier in that of his Scottish classical economist father,James Mill(1808). Mill senior restates Say's law in 1808: "production of commodities creates, and is the one and universal cause which creates a market for the commodities produced".[94]

In addition to Smith's and Say's legacies,Thomas Malthus' theories of population andDavid Ricardo'sIron law of wagesbecame central doctrines of classical economics.[88]: 76 Meanwhile, Jean-Baptiste Say challenged Smith'slabour theory of value,believing that prices were determined by utility and also emphasised the critical role of the entrepreneur in the economy. However, neither of those observations became accepted by British economists at the time. Malthus wroteAn Essay on the Principle of Populationin 1798,[88]: 71–72 becoming a major influence on classical liberalism. Malthus claimed that population growth would outstrip food production because the population grew geometrically while food production grew arithmetically. As people were provided with food, they would reproduce until their growth outstripped the food supply. Nature would then provide a check to growth in the forms of vice and misery. No gains in income could prevent this, and any welfare for the poor would be self-defeating. The poor were, in fact, responsible for their problems which could have been avoided through self-restraint.[88]: 72

Several liberals, including Adam Smith andRichard Cobden,argued that the free exchange of goods between nations would lead to world peace.[95]Smith argued that as societies progressed, the spoils of war would rise, but the costs of war would rise further, making war difficult and costly for industrialised nations.[96]Cobden believed that military expenditures worsened the state's welfare and benefited a small but concentrated elite minority, combining hisLittle Englanderbeliefs with opposition to the economic restrictions of mercantilist policies. To Cobden and many classical liberals, those who advocated peace must also advocate free markets.[97]

Utilitarianismwas seen as apolitical justificationfor implementingeconomic liberalismby British governments, an idea dominating economic policy from the 1840s. Although utilitarianism prompted legislative and administrative reform, and John Stuart Mill's later writings foreshadowed the welfare state, it was mainly used as a premise for alaissez-faireapproach.[98]: 32 The central concept of utilitarianism, developed byJeremy Bentham,was thatpublic policyshould seek to provide "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". While this could be interpreted as a justification for state action toreduce poverty,it was used by classical liberals to justify inaction with the argument that the net benefit to all individuals would be higher.[88]: 76 His philosophy proved highly influential on government policy and led to increased Benthamite attempts at governmentsocial control,includingRobert Peel'sMetropolitan Police,prison reforms,theworkhousesandasylumsfor the mentally ill.

Keynesian economics

During theGreat Depression,the English economistJohn Maynard Keynes(1883–1946) gave the definitive liberal response to the economic crisis. Keynes had been "brought up" as a classical liberal, but especially after World War I, became increasingly a welfare or social liberal.[99]A prolific writer, among many other works, he had begun a theoretical work examining the relationship between unemployment, money and prices back in the 1920s.[100]Keynes was deeply critical of the British government'sausteritymeasuresduring the Great Depression.He believedbudget deficitswere a good thing, a product ofrecessions.He wrote: "For Government borrowing of one kind or another is nature's remedy, so to speak, for preventing business losses from being, in so severe a slump as the present one, so great as to bring production altogether to a standstill".[101]At the height of the Great Depression in 1933, Keynes publishedThe Means to Prosperity,which contained specific policy recommendations for tackling unemployment in a global recession, chiefly counter cyclical public spending.The Means to Prosperitycontains one of the first mentions of themultiplier effect.[102]

Keynes'smagnum opus,The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money,was published in 1936[103]and served as a theoretical justification for theinterventionist policiesKeynes favoured for tackling a recession. TheGeneral Theorychallenged the earlierneo-classical economicparadigm, which had held that themarketwould naturally establishfull employmentequilibrium if it were unfettered by government interference.Classical economistsbelieved inSay's law,which states that "supply creates its own demand"and that in afree market,workers would always be willing to lower their wages to a level where employers could profitably offer them jobs. An innovation from Keynes was the concept ofprice stickiness,i.e. the recognition that, in reality, workers often refuse to lower their wage demands even in cases where a classical economist might argue it isrationalfor them to do so. Due in part to price stickiness, it was established that the interaction of "aggregate demand"and"aggregate supply"may lead to stable unemployment equilibria, and in those cases, it is the state and not the market that economies must depend on for their salvation. The book advocated activist economic policy by the government to stimulate demand in times of high unemployment, for example, by spending on public works. In 1928, he wrote:" Let us be up and doing, using our idle resources to increase our wealth.... With men and plants unemployed, it is ridiculous to say that we cannot afford these new developments. It is precisely with these plants and these men that we shall afford them ".[101]Where the market failed to allocate resources properly, the government was required to stimulate the economy until private funds could start flowing again—a "prime the pump" kind of strategy designed to boostindustrial production.[104]

Liberal feminist theory

Liberal feminism,the dominant tradition infeminist history,is anindividualisticform offeminist theorythat focuses on women's ability to maintain their equality through their actions and choices. Liberal feminists hope to eradicate all barriers togender equality,claiming that the continued existence of such barriers eviscerates the individual rights and freedoms ostensibly guaranteed by a liberal social order.[105]They argue that society believes women are naturallyless intellectually and physically capablethan men; thus, it tends todiscriminate against womenin theacademy,the forum and themarketplace.Liberal feminists believe that "female subordination is rooted in a set of customary and legal constraints that blocks women's entrance to and success in the so-called public world". They strive for sexual equality via political and legal reform.[106]

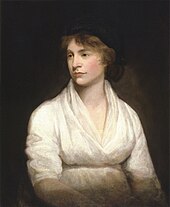

BritishphilosopherMary Wollstonecraft(1759–1797) is widely regarded as the pioneer of liberal feminism, withA Vindication of the Rights of Woman(1792) expanding the boundaries of liberalism to include women in the political structure of liberal society.[107]In her writings, such asA Vindication of the Rights of Woman,Wollstonecraft commented on society's view of women and encouraged women to use their voices in making decisions separate from those previously made for them. Wollstonecraft "denied that women are, by nature, more pleasure seeking and pleasure giving than men. She reasoned that if they were confined to the same cages that trap women, men would develop the same flawed characters. What Wollstonecraft most wanted for women was personhood".[106]

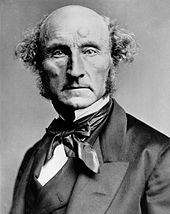

John Stuart Millwas also an early proponent of feminism. In his articleThe Subjection of Women(1861, published 1869), Mill attempted to prove that the legal subjugation of women is wrong and that it should give way to perfect equality.[108][109]He believed that both sexes should have equal rights under the law and that "until conditions of equality exist, no one can possibly assess the natural differences between women and men, distorted as they have been. What is natural to the two sexes can only be found out by allowing both to develop and use their faculties freely".[110]Mill frequently spoke of this imbalance and wondered if women were able to feel the same "genuine unselfishness" that men did in providing for their families. This unselfishness Mill advocated is the one "that motivates people to take into account the good of society as well as the good of the individual person or small family unit".[106]Like Mary Wollstonecraft, Mill compared sexual inequality to slavery, arguing that their husbands are often just as abusive as masters and that a human being controls nearly every aspect of life for another human being. In his bookThe Subjection of Women,Mill argues that three major parts of women's lives are hindering them: society and gender construction, education and marriage.[111]

Equity feminismis a form of liberal feminism discussed since the 1980s,[112][113]specifically a kind of classically liberal or libertarian feminism.[114]Steven Pinker,anevolutionary psychologist,defines equity feminism as "a moral doctrine about equal treatment that makes no commitments regarding open empirical issues in psychology or biology".[115]Barry Kuhle asserts that equity feminism is compatible withevolutionary psychologyin contrast togender feminism.[116]

Social liberal theory

Jean Charles Léonard Simonde de Sismondi'sNew Principles of Political Economy(French:Nouveaux principes d'économie politique, ou de la richesse dans ses rapports avec la population) (1819) represents the first comprehensive liberal critique of early capitalism and laissez-faire economics, and his writings, which were studied byJohn Stuart MillandKarl Marxamong many others, had a profound influence on both liberal and socialist responses to the failures and contradictions of industrial society.[117][118][119]By the end of the 19th century, theprinciples of classical liberalismwere being increasingly challenged by downturns ineconomic growth,a growing perception of theevils of poverty,unemployment and relative deprivation present within modern industrial cities, as well as the agitation oforganised labour.The ideal of theself-made individualwho could make his or her place in the world through hard work and talent seemed increasingly implausible. A major political reaction against the changes introduced byindustrialisationandlaissez-fairecapitalism came from conservatives concerned about social balance, althoughsocialismlater became a more important force for change and reform. SomeVictorian writers,includingCharles Dickens,Thomas CarlyleandMatthew Arnold,became early influential critics of social injustice.[98]: 36–37

New liberals began to adapt the old language of liberalism to confront these difficult circumstances, which they believed could only be resolved through a broader and more interventionist conception of the state. An equal right to liberty could not be established merely by ensuring that individuals did not physically interfere with each other or by having impartially formulated and applied laws. More positive and proactive measures were required to ensure that every individual would have anequal opportunityfor success.[120]

John Stuart Millcontributed enormously to liberal thought by combining elements of classical liberalism with what eventually became known as the new liberalism. Mill's 1859On Libertyaddressed the nature and limits of thepowerthat can be legitimately exercised by society over theindividual.[121]He gave an impassioned defence of free speech, arguing that freediscourseis anecessary conditionfor intellectual and social progress. Mill defined "social liberty"as protection from" the tyranny of political rulers ". He introduced many different concepts of the form tyranny can take, referred to as social tyranny andtyranny of the majority.Social liberty meant limits on the ruler's power through obtaining recognition of political liberties or rights and establishing a system of "constitutionalchecks ".[122]

His definition of liberty, influenced byJoseph PriestleyandJosiah Warren,was that theindividualought to be free to do as he wishes unless he harms others.[123]However, although Mill's initialeconomic philosophysupportedfree marketsand argued thatprogressive taxationpenalised those who worked harder,[124]he later altered his views toward a more socialist bent, adding chapters to hisPrinciples of Political Economyin defence of a socialist outlook and defending some socialist causes,[125]including the radical proposal that the whole wage system be abolished in favour of a co-operative wage system.

Another early liberal convert to greater government intervention wasT. H. Green.Seeing the effects of alcohol, he believed that the state should foster and protect the social, political and economic environments in which individuals will have the best chance of acting according to their consciences. The state should intervene only where there is a clear, proven and strong tendency of liberty to enslave the individual.[126]Green regarded the national state as legitimate only to the extent that it upholds a system of rights and obligations most likely to foster individual self-realisation.

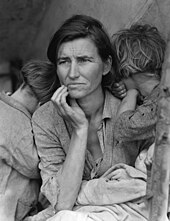

The New Liberalism or social liberalism movement emerged in about 1900 in Britain.[127]The New Liberals, including intellectuals like L. T. Hobhouse andJohn A. Hobson,saw individual liberty as something achievable only under favourable social and economic circumstances.[5]: 29 In their view, the poverty, squalor and ignorance in which many people lived made it impossible for freedom and individuality to flourish. New Liberals believed these conditions could be ameliorated only through collective action coordinated by a strong, welfare-oriented, interventionist state.[128]It supports amixed economythat includespublicand private property incapital goods.[129][130]

Principles that can be described as social liberal have been based upon or developed by philosophers such as John Stuart Mill,Eduard Bernstein,John Dewey,Carlo Rosselli,Norberto BobbioandChantal Mouffe.[131]Other important social liberal figures include Guido Calogero,Piero Gobetti,Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse andR. H. Tawney.[132]Liberal socialismhas been particularly prominent in British and Italian politics.[132]

Anarcho-capitalist theory

Classical liberalismadvocatesfree tradeunder the rule of law.Anarcho-capitalismgoes one step further, with law enforcement and the courts being provided by private companies. Various theorists have espoused legal philosophies similar to anarcho-capitalism. One of the first liberals to discuss the possibility ofprivatizingthe protection of individual liberty and property was France'sJakob Mauvillonin the 18th century. Later in the 1840s,Julius FaucherandGustave de Molinariadvocated the same. In his essayThe Production of Security,Molinari argued: "No government should have the right to prevent another government from going into competition with it, or to require consumers of security to come exclusively to it for this commodity". Molinari and this new type of anti-state liberal grounded their reasoning on liberal ideals and classical economics. Historian and libertarianRalph Raicoargued that what these liberal philosophers "had come up with was a form of individualist anarchism, or, as it would be called today, anarcho-capitalism or market anarchism".[133]Unlike the liberalism of Locke, which saw the state as evolving from society, the anti-state liberals saw a fundamental conflict between the voluntary interactions of people, i.e. society, and the institutions of force, i.e. the state. This society versus state idea was expressed in various ways: natural society vs artificial society, liberty vs authority, society of contract vs society of authority and industrial society vs militant society, to name a few.[134]The anti-state liberal tradition in Europe and the United States continued after Molinari in the early writings ofHerbert Spencerand thinkers such asPaul Émile de PuydtandAuberon Herbert.However, the first person to use the term anarcho-capitalism wasMurray Rothbard.In the mid-20th century, Rothbard synthesized elements from theAustrian Schoolof economics, classical liberalism and 19th-century Americanindividualist anarchistsLysander SpoonerandBenjamin Tucker(while rejecting theirlabour theory of valueand the norms they derived from it).[135]Anarcho-capitalism advocates the elimination of the state in favour ofindividual sovereignty,private propertyandfree markets.Anarcho-capitalistsbelieve that in the absence ofstatute(law bydecreeorlegislation), society would improve itself through the discipline of the free market (or what its proponents describe as a "voluntary society").[136][137]

In a theoreticalanarcho-capitalistsociety,law enforcement,courtsand all other security services would be operated by privately funded competitors rather than centrally throughtaxation.Moneyand othergoods and serviceswould be privately and competitively provided in anopen market.Anarcho-capitalists say personal and economic activities under anarcho-capitalism would be regulated by victim-based dispute resolution organizations undertortandcontractlaw rather than by statute through centrally determined punishment under what they describe as "political monopolies".[138]A Rothbardian anarcho-capitalist society would operate under a mutually agreed-upon libertarian "legal code which would be generally accepted, and which the courts would pledge themselves to follow".[139]Although enforcement methods vary, this pact would recognizeself-ownershipand thenon-aggression principle(NAP).

History

This section mayrequirecleanupto meet Wikipedia'squality standards.The specific problem is:Needs better presentation and content summarization.(May 2017) |

Isolated strands of liberal thought had existed inEastern philosophysince the ChineseSpring and Autumn period[140]andWestern philosophysince theAncient Greeks.The economistMurray Rothbardsuggested that ChineseTaoistphilosopherLaoziwas the first libertarian,[140]likening Laozi's ideas on government toFriedrich Hayek's theory ofspontaneous order.[141]These ideas were first drawn together and systematized as a distinct ideology by the English philosopherJohn Locke,generally regarded as the father of modern liberalism.[43][44][35][34]The first major signs of liberal politics emerged in modern times. These ideas began to coalesce at the time of theEnglish Civil War.TheLevellers,a largely ignored minority political movement that primarily consisted ofPuritans,Presbyterians,andQuakers,called forfreedom of religion,frequent convening of parliament and equality under the law. TheGlorious Revolutionof 1688 enshrinedparliamentary sovereigntyand theright of revolutionin Britain and was referred to by authorSteven Pincusas the "first modern liberal revolution".[142]The development of liberalism continued throughout the 18th century with the burgeoning Enlightenment ideals of the era. This period of profound intellectual vitality questioned old traditions and influenced severalEuropean monarchiesthroughout the 18th century. Political tension between England and itsAmerican coloniesgrew after 1765 and theSeven Years' Warover the issue oftaxation without representation,culminating in theAmerican Revolutionary Warand, eventually, theDeclaration of Independence.After the war, the leaders debated about how to move forward. TheArticles of Confederation,written in 1776, now appeared inadequate to provide security or even a functional government. TheConfederation Congresscalled aConstitutional Conventionin 1787, which resulted in the writing of a newConstitution of the United Statesestablishing afederalgovernment. In the context of the times, the Constitution was a republican and liberal document.[143][144]It remains the oldest liberal governing document in effect worldwide.

The two key events that marked the triumph of liberalism in France were theabolition of feudalism in Franceon the night of 4 August 1789, which marked the collapse of feudal and old traditional rights and privileges and restrictions, as well as the passage of theDeclaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizenin August, itself based on the U.S. Declaration of Independence from 1776.[145]During theNapoleonic Wars,the French brought Western Europe the liquidation of thefeudal system,the liberalization ofproperty laws,the end ofseigneurial dues,the abolition ofguilds,the legalization ofdivorce,the disintegration ofJewish ghettos,the collapse of theInquisition,the end of theHoly Roman Empire,the elimination of church courts and religious authority, the establishment of themetric systemand equality under the law for all men.[146]His most lasting achievement, theCivil Code,served as "an object of emulation all over the globe"[147]but also perpetuated further discrimination against women under the banner of the "natural order".[148]

The development into maturity of classical liberalism took place before and after the French Revolution in Britain.[77]Adam Smith'sThe Wealth of Nations,published in 1776, was to provide most of the ideas of economics, at least until the publication ofJohn Stuart Mill'sPrinciplesin 1848.[88]: 63, 68 Smith addressed the motivation for economic activity, the causes of prices and wealth distribution, and the policies the state should follow to maximise wealth.[88]: 64 Theradical liberal movementbegan in the 1790s in England and concentrated on parliamentary and electoral reform, emphasizing natural rights andpopular sovereignty.Radicals likeRichard PriceandJoseph Priestleysaw parliamentary reform as a first step toward dealing with their many grievances, including the treatment ofProtestant Dissenters,the slave trade, high prices and high taxes.[149][full citation needed]

InLatin America,liberal unrest dates back to the 18th century, when liberal agitation in Latin America led toindependencefrom the imperial power of Spain and Portugal. The new regimes were generally liberal in their political outlook and employed the philosophy ofpositivism,which emphasized the truth of modern science, to buttress their positions.[150]In the United States, avicious warensured the integrity of the nation and the abolition of slavery in theSouth.HistorianDon H. Doylehas argued that the Union victory in theAmerican Civil War(1861–1865) greatly boosted the course of liberalism.[151][page needed]

In the 19th century,Englishliberalpolitical philosopherswere the most influential in the global tradition of liberalism.[152]

During the 19th and early 20th century, in the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East, liberalism influenced periods of reform, such as theTanzimatandAl-Nahda;the rise of secularism, constitutionalism and nationalism; and different intellectuals and religious groups and movements, like theYoung OttomansandIslamic Modernism.Prominent of the era wereRifa'a al-Tahtawi,Namık Kemalandİbrahim Şinasi.However, the reformist ideas and trends did not reach the common population successfully, as the books, periodicals, and newspapers were accessible primarily to intellectuals and segments of the emerging middle class. ManyMuslimssaw them as foreign influences on theworld of Islam.That perception complicated reformist efforts made by Middle Eastern states.[153][154]These changes, along with other factors, helped to create a sense of crisis within Islam, which continues to this day. This led toIslamic revivalism.[155]

Abolitionistandsuffragemovements spread, along with representative and democratic ideals. France established anenduring republicin the 1870s. However, nationalism also spread rapidly after 1815. A mixture of liberal and nationalist sentiments inItalyand Germany brought about the unification of the two countries in the late 19th century. A liberal regime came to power in Italy and ended the secular power of the Popes. However, theVaticanlaunched a counter-crusade against liberalism.Pope Pius IXissued theSyllabus of Errorsin 1864, condemning liberalism in all its forms. In many countries, liberal forces responded byexpelling the Jesuit order.By the end of the nineteenth century, the principles of classical liberalism were being increasingly challenged, and the ideal of the self-made individual seemed increasingly implausible. Victorian writers likeCharles Dickens,Thomas CarlyleandMatthew Arnoldwere early influential critics of social injustice.[98]: 36–37

Liberalism gained momentum at the beginning of the 20th century. The bastion ofautocracy,theRussian Tsar,was overthrown in thefirst phaseof theRussian Revolution.The Allied victory in theFirst World Warand the collapse of four empires seemed to mark the triumph of liberalism across the European continent, not just among thevictorious alliesbut also in Germany and the newly created states ofEastern Europe.Militarism, as typified by Germany, was defeated and discredited. As Blinkhorn argues, the liberal themes were ascendant in terms of "cultural pluralism, religious and ethnic toleration, nationalself-determination,free market economics, representative and responsible government, free trade, unionism, and the peaceful settlement of international disputes through a new body, theLeague of Nations".

In the Middle East, liberalism led to constitutional periods, like the OttomanFirstandSecond Constitutional Eraand thePersian constitutional period,but it declined in the late 1930s due to the growth and opposition ofIslamismandpan-Arabnationalism.[158][159][160][161][155]However, many intellectuals advocated liberal values and ideas. Prominent liberals wereTaha Hussein,Ahmed Lutfi el-Sayed,Tawfiq al-Hakim,Abd El-Razzak El-SanhuriandMuhammad Mandur.[162]

In the United States,modern liberalismtraces its history to the popular presidency ofFranklin D. Roosevelt,who initiated theNew Dealin response to theGreat Depressionand won anunprecedented four elections.TheNew Deal coalitionestablished by Roosevelt left a strong legacy and influenced many future American presidents, includingJohn F. Kennedy.[163]Meanwhile, the definitive liberal response to the Great Depression was given by the British economistJohn Maynard Keynes,who had begun a theoretical work examining the relationship between unemployment, money and prices back in the 1920s.[164]The worldwide Great Depression, starting in 1929, hastened the discrediting of liberal economics and strengthened calls for state control over economic affairs. Economic woes prompted widespread unrest in the European political world, leading to the rise offascismas an ideology and a movement against liberalism andcommunism,especially inNazi GermanyandItaly.[165]The rise of fascism in the 1930s eventually culminated inWorld War II,the deadliest conflict in human history. TheAlliesprevailed in the war by 1945, and their victory set the stage for theCold Warbetween theCommunistEastern Blocand the liberalWestern Bloc.

In Iran,liberalism enjoyed wide popularity. In April 1951, theNational Frontbecame the governing coalition when democratically electedMohammad Mosaddegh,a liberal nationalist, took office as thePrime Minister.However, his way of governing conflicted with Western interests, and he was removed from power in acoup on 19 August 1953.The coup ended the dominance of liberalism in the country's politics.[166][167][168][169][170]

Among the various regional and national movements, thecivil rights movementin the United States during the 1960s strongly highlighted the liberal efforts forequal rights.[171]TheGreat Societyproject launched byPresidentLyndon B. Johnsonoversaw the creation ofMedicareandMedicaid,the establishment ofHead Startand theJob Corpsas part of theWar on Povertyand the passage of the landmarkCivil Rights Act of 1964,an altogether rapid series of events that some historians have dubbed the "Liberal Hour".[172]

The Cold War featured extensive ideological competition and severalproxy wars,but the widely fearedWorld War IIIbetween the Soviet Union and the United States never occurred. While communist states and liberal democracies competed against one another, aneconomic crisisin the 1970s inspired a move away fromKeynesian economics,especially underMargaret Thatcherin the United Kingdom andRonald Reaganin the United States. This trend, known asneoliberalism,constituted aparadigm shiftaway from thepost-war Keynesian consensus,which lasted from 1945 to 1980.[173][174]Meanwhile, nearing the end of the 20th century, communist states in Eastern Europecollapsed precipitously,leaving liberal democracies as the only major forms of government in the West.

At the beginning of World War II, the number of democracies worldwide was about the same as it had been forty years before.[175]After 1945, liberal democracies spread very quickly but then retreated. InThe Spirit of Democracy,Larry Diamond argues that by 1974 "dictatorship, not democracy, was the way of the world" and that "barely a quarter of independent states chose their governments through competitive, free, and fair elections". Diamond says that democracy bounced back, and by 1995 the world was "predominantly democratic".[176][177]However, liberalism still faces challenges, especially with the phenomenal growth of China as a model combination of authoritarian government and economic liberalism.[178]

Liberalism is frequently cited as the dominantideologyof themodern era.[4][5]: 11

Criticism and support

Liberalism has drawn criticism and support from various ideological groups throughout its history. Despite these complex relationships, some scholars have argued that liberalism actually "rejects ideological thinking" altogether, largely because such thinking could lead to unrealistic expectations for human society.[179]

Conservatism

The first major proponent of modern conservative thought,Edmund Burke,offered a blistering critique of the French Revolution by assailing the liberal pretensions to the power of rationality and the natural equality of all humans.[180]Conservatives have also attacked what they perceive as the reckless liberal pursuit of progress and material gains, arguing that such preoccupations undermine traditional social values rooted in community and continuity.[181]However, a few variations of conservatism, likeliberal conservatism,expound some of the same ideas and principles championed by classical liberalism, including "small government and thriving capitalism".[180]

In the bookWhy Liberalism Failed(2018),Patrick Deneenargued that liberalism has led toincome inequality,cultural decline, atomization,nihilism,the erosion of freedoms, and the growth of powerful, centralized bureaucracies.[182][183]The book also argues that liberalism has replaced old values of community, religion and tradition with self-interest.[183]

Russian PresidentVladimir Putinbelieves that "liberalism has become obsolete" and claims that the vast majority of people in the world oppose multiculturalism, immigration, and rights for LGBT people.[184]

Catholicism

One of the most outspoken early critics of liberalism was theRoman Catholic Church,which resulted in lengthy power struggles between national governments and the Church.[185]

A movement associated with modern democracy,Christian democracy,hopes to spreadCatholic social ideasand has gained a large following in some European nations.[186]The early roots of Christian democracy developed as a reaction against theindustrialisationandurbanisationassociated withlaissez-faireliberalism in the 19th century.[187]

Anarchism

Anarchists criticize theliberal social contract,arguing that it creates a state that is "oppressive, violent, corrupt, and inimical to liberty."[188]

Marxism

Karl Marxrejected the foundational aspects of liberal theory, hoping to destroy both the state and the liberal distinction between society and the individual while fusing the two into a collective whole designed to overthrow the developing capitalist order of the 19th century.[189]

Vladimir Leninstated that—in contrast withMarxism—liberal science defendswage slavery.[190][191]However, some proponents of liberalism, such asThomas Paine,George Henry Evans,andSilvio Gesell,were critics of wage slavery.[192][193]

Deng Xiaopingcriticized that liberalization would destroy the political stability of the People's Republic of China and the Chinese Communist Party, making it difficult for development to take place, and is inherently capitalistic. He termed itbourgeois liberalization.[194]Thus some socialists accuse the economic doctrines of liberalism, such as individual economic freedom, of giving rise to what they view as a system of exploitation that goes against the democratic principles of liberalism, while some liberals oppose the wage slavery that the economic doctrines of capitalism allow.[195]

Feminism

Somefeministsargue that liberalism's emphasis on distinguishing between the private and public spheres in society "allow[s] the flourishing of bigotry and intolerance in the private sphere and to require respect for equality only in the public sphere", making "liberalism vulnerable to the right-wing populist attack. Political liberalism has rejected the feminist call to recognize that thepersonal is politicaland has relied on political institutions and processes as barriers against illiberalism. "[196]

Social democracy

Social democracy,an ideology advocating modification ofcapitalismalong progressive lines, emerged in the 20th century and was influenced by socialism. Broadly defined as a project that aims to correct through government reform what it regards as the intrinsic defects of capitalism, by reducing inequality,[197]social democracy does not oppose the existence of the state. Several commentators have noted strong similarities between social liberalism and social democracy, with one political scientist calling American liberalism "bootleg social democracy" due to the absence of a significant social democratic tradition in the United States.[198]

Fascism

Fascists accuse liberalismof materialism and a lack of spiritual values.[199]In particular, fascism opposes liberalism for itsmaterialism,rationalism,individualismandutilitarianism.[200]Fascists believe that the liberal emphasis on individual freedom produces national divisiveness,[199]but many fascists agree with liberals in their support ofprivate property rightsand amarket economy.[200]

See also

- The American Prospect,an American political magazine that backs social liberal policies

- Black liberalism

- Constitutional liberalism

- Friedrich Naumann Foundation,a global advocacy organisation that supports liberal ideas and policies

- The Liberal,a former British magazine dedicated to coverage of liberal politics and liberal culture

- Liberalism by country

- Muscular liberalism

- Old Liberals

- Orange Book liberalism

- Paradox of tolerance

- Rule according to higher law

References

Notes

- ^"liberalism In general, the belief that it is the aim of politics to preserve individual rights and to maximize freedom of choice."Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics,Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan, Third edition 2009,ISBN978-0-19-920516-5.

- ^Dunn, John (1993).Western Political Theory in the Face of the Future.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-43755-4.

political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for conservatism and for tradition in general, tolerance, and... individualism.

- ^Generally support:

- Hashemi, Nader (2009).Islam, Secularism, and Liberal Democracy: Toward a Democratic Theory for Muslim Societies.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-971751-4– viaGoogle Books.

Liberal democracy requires a form of secularism to sustain itself

- Donohue, Kathleen G. (19 December 2003).Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Idea of the Consumer.New Studies in American Intellectual and Cultural History.Johns Hopkins University Press.ISBN978-0-8018-7426-0.Retrieved31 December2007– viaGoogle Books.

Three of them – freedom from fear, freedom of speech, and freedom of religion – have long been fundamental to liberalism.

- "The Economist, Volume 341, Issues 7995–7997".The Economist.1996.Retrieved31 December2007– viaGoogle Books.

For all three share a belief in the liberal society as defined above: a society that provides constitutional government (rule by law, not by men) and freedom of religion, thought, expression and economic interaction; a society in which....

- Wolin, Sheldon S. (2004).Politics and Vision: Continuity and Innovation in Western Political Thought.Princeton University Press.ISBN978-0-691-11977-9.Retrieved31 December2007– viaGoogle Books.

The most frequently cited rights included freedom of speech, press, assembly, religion, property, and procedural rights

- Firmage, Edwin Brown; Weiss, Bernard G.; Welch, John Woodland (1990).Religion and Law: Biblical-Judaic and Islamic Perspectives.Eisenbrauns.ISBN978-0-931464-39-3.Retrieved31 December2007– viaGoogle Books.

There is no need to expound the foundations and principles of modern liberalism, which emphasises the values of freedom of conscience and freedom of religion

- Lalor, John Joseph(1883).Cyclopædia of Political Science, Political Economy, and of the Political History of the United States.Nabu Press. p.760.Retrieved31 December2007.

Democracy attaches itself to a form of government: liberalism, to liberty and guarantees of liberty. The two may agree; they are not contradictory, but they are neither identical, nor necessarily connected. In the moral order, liberalism is the liberty to think, recognised and practiced. This is primordial liberalism, as the liberty to think is itself the first and noblest of liberties. Man would not be free in any degree or in any sphere of action, if he were not a thinking being endowed with consciousness. The freedom of worship, the freedom of education, and the freedom of the press are derived the most directly from the freedom to think.

- "Liberalism".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved16 June2021.constitutional governmentandprivacy rights

- Wright, Edmund, ed. (2006).The Desk Encyclopedia of World History.New York:Oxford University Press.p. 374.ISBN978-0-7394-7809-7.

- Hashemi, Nader (2009).Islam, Secularism, and Liberal Democracy: Toward a Democratic Theory for Muslim Societies.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-971751-4– viaGoogle Books.

- ^abWolfe, p. 23.

- ^abcAdams, Ian (2001)."2: Liberalism and democracy".Political Ideology Today.Politics Today (Second ed.). Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.ISBN0-7190-6019-2.

- ^abcGould, p. 3.

- ^Locke, John.Second Treatise of Government.

All mankind... being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions

- ^Kirchner, p. 3.

- ^Pincus, Steven (2009).1688: The First Modern Revolution.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-15605-8.Retrieved7 February2013.

- ^Zafirovski, Milan (2007).Liberal Modernity and Its Adversaries: Freedom, Liberalism and Anti-Liberalism in the 21st Century.Brill.p. 237.ISBN978-90-04-16052-1– viaGoogle Books.

- ^Eddy, Matthew Daniel (2017)."The Politics of Cognition: Liberalism and the Evolutionary Origins of Victorian Education".British Journal for the History of Science.50(4): 677–699.doi:10.1017/S0007087417000863.ISSN0007-0874.PMID29019300.

- ^Koerner, Kirk F. (1985).Liberalism and Its Critics.London:Routledge.ISBN978-0-429-27957-7– viaGoogle Books.

- ^Conway, Martin (2014)."The Limits of an Anti-liberal Europe".In Gosewinkel, Dieter (ed.).Anti-liberal Europe: A Neglected Story of Europeanization.Berghahn Books.p. 184.ISBN978-1-78238-426-7– viaGoogle Books.

Liberalism, liberal values and liberal institutions formed an integral part of that process of European consolidation. Fifteen years after the end of the Second World War, the liberal and democratic identity of Western Europe had been reinforced on almost all sides by the definition of the West as a place of freedom. Set against the oppression in the Communist East, by the slow development of a greater understanding of the moral horror of Nazism, and by the engagement of intellectuals and others with the new states (and social and political systems) emerging in the non-European world to the South.

- ^Stern, Sol (Winter, 2010)"The Ramparts I Watched."City Journal.

- ^Fukuyama, Francis (1989)."The End of History?".The National Interest(16): 3–18.ISSN0884-9382.JSTOR24027184.

- ^Worell, Judith.Encyclopedia of women and gender, Volume I.Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2001.ISBN0-12-227246-3

- ^"Liberalism in America: A Note for Europeans"Archived12 February 2018 at theWayback MachinebyArthur M. Schlesinger Jr.(1956) from:The Politics of Hope(Boston: Riverside Press, 1962). "Liberalism in the U.S. usage has little in common with the word as used in the politics of any other country, save possibly Britain."

- ^abcdefGross, p. 5.

- ^Kirchner, pp. 2–3.

- ^Palmer and Colton, p. 479.

- ^Kirchner, Emil J. (1988).Liberal Parties in Western Europe.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-32394-9."Liberal parties were among the first political parties to form, and their long-serving and influential records, as participants in parliaments and governments, raise important questions...."

- ^"Liberalism".Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^Rothbard, Murray (2006) [1973]."The Libertarian Heritage: The American Revolution and Classical Liberalism".For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto.Mises Institute.Archived18 June 2015 at theWayback Machine.Retrieved 18 June 2015 – via LewRockewell.com

- ^"The failure of American political speech".The Economist.6 January 2012.ISSN0013-0613.Retrieved1 September2022.

- ^Adams, Sean; Morioka, Noreen; Stone, Terry Lee (2006).Color Design Workbook: A Real World Guide to Using Color in Graphic Design.Gloucester, Mass.: Rockport Publishers. pp.86.ISBN1-59253-192-X.OCLC60393965.

- ^Kumar, Rohit Vishal; Joshi, Radhika (October–December 2006). "Colour, Colour Everywhere: In Marketing Too".SCMS Journal of Indian Management.3(4): 40–46.ISSN0973-3167.SSRN969272.

- ^Cassel-Picot, Muriel "The Liberal Democrats and the Green Cause: From Yellow to Green" in Leydier, Gilles and Martin, Alexia (2013)Environmental Issues in Political Discourse in Britain and Ireland.Cambridge Scholars Publishing.p.105Archived6 December 2022 at theWayback Machine.ISBN9781443852838

- ^"Content".Parties and Elections in Europe.2020.

- ^Puddington, p. 142. "After a dozen years of centre-left Liberal Party rule, the Conservative Party emerged from the 2006 parliamentary elections with a plurality and established a fragile minority government."

- ^Grigsby, pp. 106–07. [Talking about the Democratic Party] "Its liberalism is, for the most part, the later version of liberalism – modern liberalism."

- ^Arnold, p. 3. "Modern liberalism occupies the left-of-center in the traditional political spectrum and is represented by the Democratic Party in the United States."

- ^Cayla, David, ed. (2021).Populism and Neoliberalism.Routledge.p. 62.ISBN9781000366709– viaGoogle Books.

- ^Slomp, Hans, ed. (2011).Europe, A Political Profile: An American Companion to European Politics, Volume 1.ABC-CLIO.pp. 106–108.ISBN9780313391811– viaGoogle Books.

- ^abBevir, Mark (2010).Encyclopedia of Political Theory: A–E, Volume 1.SAGE Publications.p. 164.ISBN978-1-4129-5865-3.Retrieved19 May2017– viaGoogle Books.

- ^abFung, Edmund S. K. (2010).The Intellectual Foundations of Chinese Modernity: Cultural and Political Thought in the Republican Era.Cambridge University Press.p. 130.ISBN978-1-139-48823-5.Retrieved16 May2017– viaGoogle Books.

- ^Antoninus, p. 3.

- ^Young 2002,pp. 25–26.

- ^abYoung 2002,p. 24.

- ^Young 2002,p. 25.

- ^abGray, p. xii.

- ^Wolfe, pp. 33–36.

- ^Young 2002,p. 45.

- ^abTaverne, p. 18.

- ^abGodwin et al., p. 12.

- ^Copleston, Frederick.A History of Philosophy: Volume V.New York: Doubleday, 1959.ISBN0-385-47042-8pp. 39–41.

- ^Young 2002,pp. 30–31

- ^Locke, John(1947).Two Treatises of Government.New York: Hafner Publishing Company.

- ^Forster, p. 219.

- ^Zvesper, Dr John (4 March 1993).Nature and Liberty.Routledge.p. 93.ISBN9780415089234.

- ^Copleston, Frederick.A History of Philosophy: Volume V.New York: Doubleday, 1959.ISBN0-385-47042-8,p. 33.

- ^abcKerber, Linda(1976). "The Republican Mother: Women and the Enlightenment-An American Perspective".American Quarterly.28(2): 187–205.doi:10.2307/2712349.JSTOR2712349.

- ^Feldman, Noah (2005).Divided by God.Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 29 ( "It tookJohn Locketo translate the demand for liberty of conscience into a systematic argument for distinguishing the realm of government from the realm of religion. ")

- ^Feldman, Noah (2005).Divided by God.Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 29

- ^McGrath, Alister.1998.Historical Theology, An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought.Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 214–15.

- ^Bornkamm, Heinrich (1962), "Toleranz. In der Geschichte des Christentums",Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart(in German),3. Auflage, Band VI, col. 942

- ^Hunter, William Bridges.A Milton Encyclopedia, Volume 8(East Brunswick, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1980). pp. 71, 72.ISBN0-8387-1841-8.

- ^Wertenbruch, W (1960), "Menschenrechte",Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart(in German), Tübingen, DE

{{citation}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link),3. Auflage, Band IV, col. 869 - ^abcYoung 2002,p. 30.

- ^abYoung 2002,p. 31.

- ^Young 2002,p. 32.

- ^Young 2002,pp. 32–33.

- ^abGould, p. 4.

- ^abYoung 2002,p. 33.

- ^Wolfe, p. 74.

- ^Tenenbaum, Susan (1980). "The Coppet Circle. Literary Criticism as Political Discourse".History of Political Thought.1(2): 453–473.

- ^Lefevere, Andre (2016).Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame.Taylor & Francis. p. 109.

- ^Fairweather, Maria (2013).Madame de Stael.Little, Brown Book Group.

- ^Hofmann, Etienne; Rosset, François (2005).Le Groupe de Coppet. Une constellation d'intellectuels européens.Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes.

- ^Jaume, Lucien (2000).Coppet, creuset de l'esprit libéral: Les idées politiques et constitutionnelles du Groupe de Madame de Staël.Presses Universitaires d'Aix-Marseille. p. 10.

- ^Delon, Michel (1996). "Le Groupe de Coppet". In Francillon, Roger (ed.).Histoire de la littérature en Suisse romande t.1.Payot.

- ^"The Home of French Liberalism".The Coppet Institute.Retrieved20 February2020.

- ^Kete, Kathleen (2012).Making Way for Genius: The Aspiring Self in France from the Old Regime to the New.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-17482-3.

- ^abcd"Constant, Benjamin, 1988, 'The Liberty of the Ancients Compared with that of the Moderns' (1819), in The Political Writings of Benjamin Constant, ed. Biancamaria Fontana, Cambridge, pp. 309–28".Uark.edu. Archived fromthe originalon 5 August 2012.Retrieved17 September2013.

- ^Bertholet, Auguste (2021)."Constant, Sismondi et la Pologne".Annales Benjamin Constant.46:65–76.