Anti-fascism

| Part ofa serieson |

| Anti-fascism |

|---|

|

Anti-fascismis apolitical movementin opposition tofascistideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and duringWorld War II,where theAxis powerswere opposed by many countries forming theAllies of World War IIand dozens ofresistance movementsworldwide. Anti-fascism has been an element of movements across the political spectrum and holding many different political positions such asanarchism,communism,pacifism,republicanism,social democracy,socialismandsyndicalismas well ascentrist,conservative,liberalandnationalistviewpoints.

Fascism, afar-rightultra-nationalisticideology best known for its use by theItalian Fascistsand theNazis,became prominent beginning in the 1910s. Organization against fascism began around 1920. Fascism became the state ideology of Italy in 1922 and of Germany in 1933, spurring a large increase in anti-fascist action, includingGerman resistance to Nazismand theItalian resistance movement.Anti-fascism was a major aspect of theSpanish Civil War,which foreshadowed World War II.

Before World War II,the Westhad not taken seriously the threat of fascism, and anti-fascism was sometimes associated with communism. However, theoutbreak of World War IIgreatly changed Western perceptions, and fascism was seen as an existential threat by not only thecommunistSoviet Union but also by theliberal-democraticUnited States and United Kingdom. The Axis Powers of World War II were generally fascist, and the fight against them was characterized in anti-fascist terms.Resistance during World War IIto fascism occurred in every occupied country, and came from across the ideological spectrum. The defeat of the Axis powers generally ended fascism as a state ideology.

After World War II, the anti-fascist movement continued to be active in places where organized fascism continued or re-emerged. There was a resurgence ofantifa in Germanyin the 1980s, as a response to the invasion of thepunk scenebyneo-Nazis.This influenced theantifa movement in the United Statesin the late 1980s and 1990s, which was similarly carried by punks. In the 21st century, this greatly increased in prominence as a response to the resurgence of theradical right,especially after theelection of Donald Trump.[1][2]

Origins

[edit]

With the development and spread ofItalian Fascism,i.e. the original fascism, theNational Fascist Party's ideology was met with increasingly militant opposition by Italian communists and socialists. Organizations such asArditi del Popolo[3]and theItalian Anarchist Unionemerged between 1919 and 1921, to combat the nationalist and fascist surge of the post-World War I period.

In the words of historianEric Hobsbawm,as fascism developed and spread, a "nationalism of the left" developed in those nations threatened by Italianirredentism(e.g. in theBalkans,andAlbaniain particular).[4]After the outbreak of World War II, theAlbanianandYugoslavresistances were instrumental in antifascist action and underground resistance. This combination of irreconcilable nationalisms andleftistpartisans constitute the earliest roots of European anti-fascism. Less militant forms of anti-fascism arose later. During the 1930s in Britain, "Christians – especially theChurch of England– provided both a language of opposition to fascism and inspired anti-fascist action ".[5]French philosopherGeorges Bataillebelieved thatFriedrich Nietzschewas a forerunner of anti-fascism due to his derision for nationalism and racism.[6]

Michael Seidman argues that traditionally anti-fascism was seen as the purview of thepolitical leftbut that in recent years this has been questioned. Seidman identifies two types of anti-fascism, namely revolutionary and counterrevolutionary:[7]

- Revolutionary anti-fascism was expressed amongst communists and anarchists, where it identified fascism and capitalism as its enemies and made little distinction between fascism and other forms of right-wing authoritarianism.[8]It did not disappear after the Second World War but was used as an official ideology of the Soviet bloc, with the "fascist" West as the new enemy.

- Counterrevolutionary anti-fascism was much more conservative in nature, with Seidman arguing that Charles de Gaulle and Winston Churchill represented examples of it and that they tried to win the masses to their cause. Counterrevolutionary antifascists desired to ensure the restoration or continuation of the prewar old regime and conservative antifascists disliked fascism's erasure of the distinction between the public and private spheres. Like its revolutionary counterpart, it would outlast fascism once the Second World War ended.

Seidman argues that despite the differences between these two strands of anti-fascism, there were similarities. They would both come to regard violent expansion as intrinsic to the fascist project. They both rejected any claim that theVersailles Treatywas responsible for the rise of Nazism and instead viewed fascist dynamism as the cause of conflict. Unlike fascism, these two types of anti-fascism did not promise a quick victory but an extended struggle against a powerful enemy. During World War II, both anti-fascisms responded to fascist aggression by creating a cult of heroism which relegated victims to a secondary position.[7]However, after the war, conflict arose between the revolutionary and counterrevolutionary anti-fascisms; the victory of the Western Allies allowed them to restore the old regimes of liberal democracy in Western Europe, while Soviet victory in Eastern Europe allowed for the establishment of new revolutionary anti-fascist regimes there.[9]

History

[edit]

Anti-fascist movements emerged first in Italy during the rise ofBenito Mussolini,[10]but they soon spread to other European countries and then globally. In the early period, Communist, socialist, anarchist and Christian workers and intellectuals were involved. Until 1928, the period of theUnited front,there was significant collaboration between the Communists and non-Communist anti-fascists.

In 1928, theCominterninstituted itsultra-leftThird Periodpolicies, ending co-operation with other left groups, and denouncing social democrats as "social fascists".From 1934 until theMolotov–Ribbentrop Pact,the Communists pursued aPopular Frontapproach, of building broad-based coalitions with liberal and even conservative anti-fascists. As fascism consolidated its power, and especially duringWorld War II,anti-fascism largely took the form ofpartisanorresistancemovements.

Italy: against Fascism and Mussolini

[edit]

In Italy, Mussolini'sFascistregime used the termanti-fascistto describe its opponents. Mussolini'ssecret policewas officially known as theOrganization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism.During the 1920s in theKingdom of Italy,anti-fascists, many of them from thelabor movement,fought against the violentBlackshirtsand against the rise of the fascist leader Benito Mussolini. After theItalian Socialist Party(PSI) signed apacification pactwith Mussolini and hisFasces of Combaton 3 August 1921,[11]and trade unions adopted a legalist and pacified strategy, members of the workers' movement who disagreed with this strategy formedArditi del Popolo.[12]

TheItalian General Confederation of Labour(CGL) and the PSI refused to officially recognize the anti-fascist militia and maintained a non-violent, legalist strategy, while theCommunist Party of Italy(PCd'I) ordered its members to quit the organization. The PCd'I organized some militant groups, but their actions were relatively minor.[13]The Italian anarchistSeverino Di Giovanni,who exiled himself to Argentina following the 1922March on Rome,organized several bombings against the Italian fascist community.[14]The Italian liberal anti-fascistBenedetto Crocewrote hisManifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals,which was published in 1925.[15]Other notable Italian liberal anti-fascists around that time werePiero GobettiandCarlo Rosselli.[16]

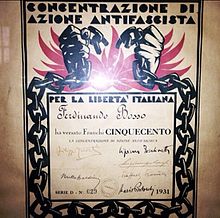

Concentrazione Antifascista Italiana(English:Italian Anti-Fascist Concentration), officially known as Concentrazione d'Azione Antifascista (Anti-Fascist Action Concentration), was an Italian coalition of Anti-Fascist groups which existed from 1927 to 1934. Founded inNérac,France, by expatriate Italians, the CAI was an alliance of non-communist anti-fascist forces (republican, socialist, nationalist) trying to promote and to coordinate expatriate actions to fight fascism in Italy; they published a propaganda paper entitledLa Libertà.[17][18][19]

Giustizia e Libertà(English:Justice and Freedom) was an Italiananti-fascistresistance movement,active from 1929 to 1945.[20]The movement was cofounded byCarlo Rosselli,[20]Ferruccio Parri,who later becamePrime Minister of Italy,andSandro Pertini,who becamePresident of Italy,were among the movement's leaders.[21]The movement's members held various political beliefs but shared a belief in active, effective opposition to fascism, compared to the older Italian anti-fascist parties.Giustizia e Libertàalso made the international community aware of the realities of fascism in Italy, thanks to the work ofGaetano Salvemini.

Many Italian anti-fascists participated in theSpanish Civil Warwith the hope of setting an example of armed resistance toFranco's dictatorship against Mussolini's regime; hence their motto: "Today in Spain, tomorrow in Italy".[22]

Between 1920 and 1943, several anti-fascist movements were active among theSlovenesandCroatsin the territories annexed to Italy afterWorld War I,known as theJulian March.[23][24]The most influential was the militant insurgent organizationTIGR,which carried out numerous sabotages, as well as attacks on representatives of the Fascist Party and the military.[25][26]Most of the underground structure of the organization was discovered and dismantled by theOrganization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism(OVRA) in 1940 and 1941,[27]and after June 1941 most of its former activists joined theSlovene Partisans.

DuringWorld War II,many members of theItalian resistanceleft their homes and went to live in the mountains, fighting against Italian fascists andGerman Nazisoldiers during theItalian Civil War.Many cities in Italy, includingTurin,NaplesandMilan,were freed by anti-fascist uprisings.[28]

Slovenians and Croats under Italianization

[edit]The anti-fascist resistance emerged within theSlovene minority in Italy (1920–1947),whom the Fascists meant todepriveof their culture, language and ethnicity.[citation needed]The 1920 burning of theNational Hall in Trieste,theSlovenecenter in the multi-cultural and multi-ethnicTriesteby the Blackshirts,[29]was praised by Benito Mussolini (yet to become Il Duce) as a "masterpiece of the Triestine fascism" (capolavoro del fascismo triestino).[30]The use of Slovene in public places, including churches, was forbidden, not only in multi-ethnic areas, but also in the areas where the population was exclusively Slovene.[31]Children, if they spoke Slovene, were punished by Italian teachers who were brought by the Fascist State fromSouthern Italy.Slovene teachers, writers, and clergy were sent to the other side of Italy.

The first anti-fascist organization, calledTIGR,was formed by Slovenes and Croats in 1927 in order to fight Fascist violence. Its guerrilla fight continued into the late 1920s and 1930s.[32]By the mid-1930s, 70,000 Slovenes had fled Italy, mostly toSlovenia(then part of Yugoslavia) andSouth America.[33]

The Slovene anti-fascist resistance inYugoslaviaduring World War II was led byLiberation Front of the Slovenian People.TheProvince of Ljubljana,occupied by Italian Fascists, saw the deportation of 25,000 people, representing 7.5% of the total population, filling up theRab concentration campandGonars concentration campas well as otherItalian concentration camps.

Germany: against the NSDAP and Hitlerism

[edit]

The specific term anti-fascism was primarily used[citation needed]by theCommunist Party of Germany(KPD), which held the view that it was the only anti-fascist party in Germany. The KPD formed several explicitly anti-fascist groups such asRoter Frontkämpferbund(formed in 1924 and banned by theSocial Democratsin 1929) andKampfbund gegen den Faschismus(ade factosuccessor to the latter).[34][35][need quotation to verify][36][need quotation to verify]At its height,Roter Frontkämpferbundhad over 100,000 members. In 1932, the KPD established theAntifaschistische Aktionas a "red united front under the leadership of the only anti-fascist party, the KPD".[37]Under the leadership of the committedStalinistErnst Thälmann,the KPD primarily viewed fascism as the final stage ofcapitalismrather than as a specific movement or group, and therefore applied the term broadly to its opponents, and in the name of anti-fascism the KPD focused in large part on attacking its main adversary, the centre-leftSocial Democratic Party of Germany,whom they referred to associal fascistsand regarded as the "main pillar of the dictatorship of Capital."[38]

The movement ofNazism,which grew ever more influential in the last years of theWeimar Republic,was opposed for different ideological reasons by a wide variety of groups, including groups which also opposed each other, such as social democrats, centrists, conservatives and communists. The SPD and centrists formedReichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Goldin 1924 to defendliberal democracyagainst both the Nazi Party and the KPD, and their affiliated organizations. Later, mainly SPD members formed theIron Frontwhich opposed the same groups.[39]

The name and logo ofAntifaschistische Aktionremain influential. Its two-flag logo, designed byMax GebhardandMax Keilson,is still widely used as a symbol of militant anti-fascists in Germany and globally,[40]as is the Iron Front'sThree Arrowslogo.[41]

Spain: Civil War against the Nationalists

[edit]

The historianEric Hobsbawmwrote: "TheSpanish civil warwas both at the centre and on the margin of the era of anti-fascism. It was central, since it was immediately seen as a European war between fascism and anti-fascism, almost as the first battle in the coming world war, some of the characteristic aspects of which – for example, air raids against civilian populations – it anticipated. "[42]

In Spain, there were histories of popular uprisings in the late 19th century through to the 1930s against the deep-seated military dictatorships.[43]of General Prim and the Primo de la Rivieras[44]These movements further coalesced into large-scale anti-fascist movements in the 1930s, many in the Basque Country, before and during theSpanish Civil War.Therepublicangovernment and army, theAntifascist Worker and Peasant Militias(MAOC) linked to theCommunist Party(PCE),[45]theInternational Brigades,theWorkers' Party of Marxist Unification(POUM),Spanish anarchistmilitias,such as theIron Columnand the autonomous governments ofCataloniaand theBasque Country,fought the rise ofFrancisco Francowith military force.

TheFriends of Durruti,associated with theFederación Anarquista Ibérica(FAI), were a particularly militant group. Thousands of people from many countries went to Spain in support of the anti-fascist cause, joining units such as theAbraham Lincoln Brigade,theBritish Battalion,theDabrowski Battalion,theMackenzie-Papineau Battalion,theNaftali Botwin Companyand theThälmann Battalion,includingWinston Churchill's nephew,Esmond Romilly.[46]Notable anti-fascists who worked internationally against Franco included:George Orwell(who fought in the POUM militia and wroteHomage to Cataloniaabout his experience),Ernest Hemingway(a supporter of the International Brigades who wroteFor Whom the Bell Tollsabout his experience), and the radical journalistMartha Gellhorn.

The Spanish anarchistguerrillaFrancesc Sabaté Llopartfought against Franco's regime until the 1960s, from a base in France. TheSpanish Maquis,linked to the PCE, also fought the Franco regime long after the Spanish Civil war had ended.[47]

France: againstAction Françaiseand Vichy

[edit]

In the 1920s and 1930s in theFrench Third Republic,anti-fascists confronted aggressivefar-rightgroups such as theAction Françaisemovement in France, which dominated theLatin Quarterstudents' neighborhood.[citation needed]After fascism triumphed via invasion, the French Resistance (French:La Résistance française) or, more accurately,resistance movementsfought against theNazi Germanoccupation and against the collaborationistVichy régime.Resistance cells were small groups of armed men and women (called themaquisin rural areas), who, in addition to theirguerrilla warfareactivities, were also publishers ofunderground newspapers and magazinessuch asArbeiter und Soldat(Worker and Soldier) during World War Two, providers of first-hand intelligence information, and maintainers of escape networks.[citation needed]

United Kingdom: against Mosley's BUF

[edit]The rise ofOswald Mosley'sBritish Union of Fascists(BUF) in the 1930s was challenged by theCommunist Party of Great Britain,socialistsin theLabour PartyandIndependent Labour Party,anarchists,IrishCatholicdockmen andworking classJewsinLondon's East End.A high point in the struggle was theBattle of Cable Street,when thousands of local residents and others turned out to stop the BUF from marching. Initially, the national Communist Party leadership wanted a mass demonstration atHyde Parkin solidarity withRepublican Spain,instead of a mobilization against the BUF, but local party activists argued against this. Activists rallied support with the sloganThey shall not pass,adopted from Republican Spain.

There were debates within the anti-fascist movement over tactics. While many East End ex-servicemen participated in violence against fascists,[48]Communist Party leaderPhil Piratindenounced these tactics and instead called for large demonstrations.[49]In addition to the militant anti-fascist movement, there was a smaller current of liberal anti-fascism in Britain; SirErnest Barker,for example, was a notable English liberal anti-fascist in the 1930s.[50]

United States, World War II

[edit]

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded theMazzini SocietyinNorthampton, Massachusettsin September 1939 to work toward ending Fascist rule in Italy. As political refugees from Mussolini's regime, they disagreed among themselves whether to ally with Communists and anarchists or to exclude them. The Mazzini Society joined with other anti-Fascist Italian expatriates in the Americas at a conference inMontevideo,Uruguay in 1942. They unsuccessfully promoted one of their members,Carlo Sforza,to become the post-Fascist leader of a republican Italy. The Mazzini Society dispersed after the overthrow of Mussolini as most of its members returned to Italy.[51][52]

During theSecond Red Scarewhich occurred in the United States in the years that immediately followed the end ofWorld War II,the term "premature anti-fascist" came into currency and it was used to describe Americans who had strongly agitated or worked against fascism, such as Americans who had fought for theRepublicansduring theSpanish Civil War,before fascism was seen as a proximate and existential threat to the United States (which only occurred generally after theinvasion of PolandbyNazi Germanyand only occurred universally after theattack on Pearl Harbor). The implication was that such persons were either Communists or Communist sympathizers whose loyalty to the United States was suspect.[53][54][55]However, the historiansJohn Earl HaynesandHarvey Klehrhave written that no documentary evidence has been found of the US government referring to American members of theInternational Brigadesas "premature antifascists": theFederal Bureau of Investigation,Office of Strategic Services,andUnited States Armyrecords used terms such as "Communist", "Red", "subversive", and "radical" instead. Indeed, Haynes and Klehr indicate that they have found many examples of members of theXV International Brigadeand their supporters referring to themselves sardonically as "premature antifascists".[56]

Burma, World War II

[edit]TheAnti-Fascist Organisation(AFO) was aresistance movementwhich advocated the independence of Burma and fought against theJapanese occupation of BurmaduringWorld War II.It was the forerunner of theAnti-Fascist People's Freedom League.The AFO was formed during a meeting which was held inPeguin August 1944, the meeting was held by the leaders of theCommunist Party of Burma(CPB), theBurma National Army(BNA) led by GeneralAung San,and the People's Revolutionary Party (PRP), later renamed theBurma Socialist Party.[57][58]Whilst in Insein prison in July 1941, CPB leadersThakin Than TunandThakin Soehad co-authored theInsein Manifesto,which, against the prevailing opinion in the Burmese nationalist movement led by theDobama Asiayone,identified worldfascismas the main enemy in the coming war and called for temporary cooperation with the British in a broad allied coalition that included theSoviet Union.Soe had already gone underground to organise resistance against the Japanese occupation, and Than Tun as Minister of Land and Agriculture was able to pass on Japanese intelligence to Soe, while other Communist leaders Thakin Thein Pe and Thakin Tin Shwe made contact with the exiled colonial government inSimla,India.Aung San was War Minister in the puppet administration which was set up on 1 August 1943 and included the Socialist leadersThakin NuandThakin Mya.[57][58]During a meeting which was held between 1 and 3 March 1945, the AFO was reorganized as a multi-party front which was named theAnti-Fascist People's Freedom League.[59]

Poland, World War II

[edit]

The Anti-Fascist Bloc was an organization ofPolish Jewsformed in the March 1942 in theWarsaw Ghetto.It was created after an alliance betweenleftist-Zionist,communist and socialist Jewish parties was agreed upon. The initiators of the bloc wereMordechai Anielewicz,Józef Lewartowski(Aron Finkelstein) from thePolish Workers' Party,Josef KaplanfromHashomer Hatzair,Szachno SaganfromPoale Zion-Left,Jozef Sakas a representative of socialist-Zionists andIzaak Cukiermanwith his wifeCywia LubetkinfromDror.TheJewish Bunddid not join the bloc though they were represented at its first conference byAbraham BlumandMaurycy Orzech.[60][61][62][63]

After World War II

[edit]

The anti-fascist movements which emerged during the period of classical fascism, both liberal and militant, continued to operate after the defeat of theAxis powersin response to the resilience and mutation of fascism both in Europe and elsewhere. In Germany, as Nazi rule crumbled in 1944, veterans of the 1930s anti-fascist struggles formedAntifaschistische Ausschüsse,Antifaschistische Kommittees,orAntifaschistische Aktiongroups, all typically abbreviated to "antifa".[64]The socialist government ofEast Germanybuilt theBerlin Wallin 1961, and theEastern Blocreferred to it officially as the "Anti-fascist Protection Rampart". Resistance to fascists dictatorships in Spain and Portugal continued, including the activities of theSpanish Maquisand others, leading up to theSpanish transition to democracyand theCarnation Revolution,respectively, as well as to similar dictatorships inChileand elsewhere. Other notable anti-fascist mobilisations in the first decades of the post-war period include the43 Groupin Britain.[65]

With the start of theCold Warbetween the former World War II allies of the United States and the Soviet Union, the concept oftotalitarianismbecame prominent in Westernanti-communistpolitical discourse as a tool to convert pre-war anti-fascism into post-war anti-communism.[66][67][68][69][70]

Modern antifa politics can be traced to opposition to the infiltration of Britain'spunkscene bywhite power skinheadsin the 1970s and 1980s, and the emergence ofneo-Nazismin Germany following thefall of the Berlin Wall.In Germany, young leftists, including anarchists and punk fans, renewed the practice of street-level anti-fascism. ColumnistPeter Beinartwrites that "in the late '80s, left-wing punk fans in the United States began following suit, though they initially called their groupsAnti-Racist Action(ARA) on the theory that Americans would be more familiar with fighting racism than they would be with fighting fascism ".[71]

Germany

[edit]The contemporary antifa movement in Germany comprises different anti-fascist groups which usually use the abbreviation antifa and regard the historicalAntifaschistische Aktion(Antifa) of the early 1930s as an inspiration, drawing on the historic group for its aesthetics and some of its tactics, in addition to the name. Many new antifa groups formed from the late 1980s onward. According to Loren Balhorn, contemporary antifa in Germany "has no practical historical connection to the movement from which it takes its name but is instead a product of West Germany's squatter scene and autonomist movement in the 1980s".[72]

One of the biggest antifascist campaigns in Germany in recent years was the ultimately successful effort toblock the annual Nazi-ralliesin the east German city of Dresden in Saxony which had grown into "Europe's biggest gathering of Nazis".[73]Unlike the original Antifa which had links to theCommunist Party of Germanyand which was concerned with industrial working-class politics, the late 1980s and early 1990s,autonomistswere independentanti-authoritarianlibertarian Marxistsandanarcho-communistsnot associated with any particular party. The publicationAntifaschistisches Infoblatt,in operation since 1987, sought to exposeradical nationalistspublicly.[74]

German governmentinstitutions such as theFederal Office for the Protection of the Constitutionand theFederal Agency for Civic Educationdescribe the contemporary antifa movement as part of the extreme left and as partially violent. Antifa groups are monitored by the federal office in the context of its legal mandate to combatextremism.[75][76][77][78]The federal office states that the underlying goal of the antifa movement is "the struggle against theliberal democratic basic order"and capitalism.[76][77]In the 1980s, the movement was accused by German authorities of engaging interroristacts of violence.[79]

Greece

[edit]In Greece, anti-fascism is a popular part of leftist and anarchist culture, September 2013 anti-fascist hip-hop artistPavlos 'Killah P' Fyssaswas accosted and attacked with bats and knives by a large group ofGolden Dawnaffiliated people leaving Pavlos to be pronounced dead at the hospital. The attack lead international protests and riots, the retaliatoryshooting of three Golden Dawn membersoutside of theirNeo Irakleioas well as condemnations against the party by politicians and other public figures, includingPrime MinisterAntonis Samaras.[citation needed]This episode led to Golden Dawn to being criminally investigated, with the result in sixty-eight members of Golden Dawn being declared part of a criminal organization whilst fifteen out of the seventeen members accused in Pavlos's murder were convicted,[80]"Effectively banning" the party.[81]

Italy

[edit]

Today'sItalian constitutionis the result of the work of theConstituent Assembly,which was formed by the representatives of all the anti-fascist forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during theliberation of Italy.[82]

Liberation Dayis a national holiday inItalythat commemorates the victory of theItalian resistance movementagainstNazi Germanyand theItalian Social Republic,puppet stateof the Nazis andrump stateof the fascists, in theItalian Civil War,acivil warin Italy fought duringWorld War II,which takes place on 25 April. The date was chosen by convention, as it was the day of the year 1945 when theNational Liberation Committeeof Upper Italy (CLNAI) officially proclaimed the insurgency in a radio announcement, propounding the seizure of power by the CLNAI and proclaiming the death sentence for all fascist leaders (includingBenito Mussolini,who was shot three days later).[83]

Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia(ANPI; "National Association of ItalianPartisans") is an association founded by participants of theItalian resistanceagainst theItalian Fascistregime and the subsequentNazioccupation duringWorld War II.ANPI was founded inRomein 1944[84]while the war continued innorthern Italy.It was constituted as acharitable foundationon 5 April 1945. It persists due to the activity of its antifascist members. ANPI's objectives are the maintenance of the historical role of the partisan war by means of research and the collection of personal stories. Its goals are a continued defense againsthistorical revisionismand the ideal and ethical support of the high values of freedom and democracy expressed in the 1948constitution,in which the ideals of theItalian resistancewere collected.[85]Since 2008, every two years ANPI organizes its national festival. During the event, meetings, debates, and musical concerts that focus on antifascism, peace, and democracy are organized.[86]

Bella ciao(Italian pronunciation:[ˈbɛllaˈtʃaːo];"Goodbye beautiful" ) is anItalian folk songmodified and adopted as an anthem of theItalian resistance movementby the partisans who opposednazismandfascism,and fought against the occupying forces ofNazi Germany,who were allied with the fascist and collaborationistItalian Social Republicbetween 1943 and 1945 during theItalian Civil War.Versions of this Italian anti-fascist song continue to be sung worldwide as a hymn of freedom and resistance.[87]As an internationally known hymn of freedom, it was intoned at many historic and revolutionary events. The song originally aligned itself with Italian partisans fighting against Nazi German occupation troops, but has since become to merely stand for the inherent rights of all people to be liberated from tyranny.[88][89]

United States

[edit]Dartmouth Collegehistorian Mark Bray, author ofAntifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook,credits the ARA as the precursor of modern antifa groups in the United States. In the late 1980s and 1990s, ARA activists toured with popular punk rock and skinhead bands in order to preventKlansmen,neo-Nazis and other assorted white supremacists from recruiting.[90][91]Their motto was "We go where they go" by which they meant that they would confrontfar-rightactivists in concerts and actively remove their materials from public places.[92]In 2002, the ARA disrupted a speech in Pennsylvania byMatthew F. Hale,the head of the white supremacist groupWorld Church of the Creator,resulting in a fight and twenty-five arrests. In 2007,Rose City Antifa,likely the first group to utilize the name antifa, was formed inPortland, Oregon.[93][94][95]Other antifa groups in the United States have other genealogies. In 1987 inBoise, Idaho,the Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment (NWCAMH) was created in response to the Aryan Nation's annual meeting nearHayden Lake, Idaho.The NWCAMH brought together over 200 affiliated public and private organizations, and helped people, across six states--Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington and Wyoming.[96]InMinneapolis, Minnesota,a group called the Baldies was formed in 1987 with the intent to fight neo-Nazi groups directly. In 2013, the "most radical" chapters of the ARA formed theTorch Antifa Network[97]which has chapters throughout the United States.[98]Other antifa groups are a part of different associations such as NYC Antifa or operate independently.[99]

Modern antifa in the United States is a highlydecentralizedmovement. Antifapolitical activistsareanti-racistswho engage inprotesttactics, seeking to combatfascistsandracistssuch asneo-Nazis,white supremacists,and otherfar-rightextremists.[100]This may involvedigital activism,harassment,physical violence,andproperty damage[101]against those whom they identify as belonging to the far-right.[102][103]According to antifa historian Mark Bray, most antifa activity is nonviolent, involving poster and flyer campaigns, delivering speeches, marching in protest, and community organizing on behalf of anti-racist and anti-white nationalistcauses.[104][94]

A June 2020 study by theCenter for Strategic and International Studiesof 893 terrorism incidents in the United States since 1994 found one attack staged by an anti-fascist that led to a fatality (the2019 Tacoma attack,in which the attacker, who identified as an anti-fascist, was killed by police), while attacks by white supremacists or other right-wing extremists resulted in 329 deaths.[105][106][107]Since the study was published, onehomicidehas been connected to anti-fascism.[105]ADHSdraft report from August 2020 similarly did not include "antifa" as a considerable threat, while noting white supremacists as the top domestic terror threat.[108]

There have been multiple efforts to discredit antifa groups via hoaxes on social media, many of themfalse flagattacks originating fromalt-rightand4chanusers posing as antifa backers onTwitter.[109][110]Some hoaxes have been picked up and reported as fact by right-leaning media.[111][112]

During theGeorge Floyd protestsin May and June 2020, theTrump administrationblamed antifa for orchestrating the mass protests. Analysis of federal arrests did not find links to antifa.[113]There had been repeated calls by the Trump administration to designate antifa as a terrorist organization,[114]a move that academics, legal experts and others argued would both exceed the authority of the presidency and violate theFirst Amendment.[115][116][117]

Elsewhere

[edit]Some post-war anti-fascist action took place inRomaniaunder theAnti-Fascist Committee of German Workers in Romania,founded in March 1949.[118]A Swedish group,Antifascistisk Aktion,was formed in 1993.[119]

Use of the term

[edit]TheChristian Democratic Union of GermanypoliticianTim Petersnotes that the term is one of the most controversial terms inpolitical discourse.[120]Michael Richter,a researcher at theHannah Arendt Institute for Research on Totalitarianism,highlights the ideological use of the term in the Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc, in which the termfascismwas applied toEastern bloc dissidentsregardless of any connection to historical fascism, and where the termanti-fascismserved to legitimize the ruling government.[121]

See also

[edit]- Anti anti-communism

- Anti-authoritarianism

- Anti-capitalism

- Anti-Chinilpa(Korea)

- Anti-Germans (political current)

- Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia

- Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Serbia

- Anti-Fascist Committee of Cham Immigrants

- Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia

- Antifascist Front of Slavs in Hungary

- Anti-racism

- Anti-Stalinist left

- Denazification

- Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

- All-Slavic Anti-Fascist Committee

- Laws against Holocaust denial

- Resistance during World War II

- Redskin (subculture)

- Slovak National Uprising

- Squadism

Notes

[edit]- ^Beinart, Peter (6 August 2017)."The Rise of the Violent Left".The Atlantic.Retrieved21 October2020.

- ^Beauchamp, Zack (8 June 2020)."Antifa, explained".Vox.Retrieved21 October2020.

- ^Gli Arditi del Popolo (Birth)Archived7 August 2008 at theWayback Machine(in Italian)

- ^Hobsbawm, Eric (1992).The Age of Extremes.Vintage. pp.136–37.ISBN978-0394585758.

- ^Lawson, Tom (2010).Varieties of Anti-Fascism: Britain in the Inter-War Period.Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 119–139.ISBN978-1-349-28231-9.

- ^LaCoss, D.W. (2001).The Revolutionary Politics of Surrealism in Paris, 1934-9.University of Michigan.Retrieved17 March2023.

- ^abSeidman, Michael. Transatlantic Antifascisms: From the Spanish Civil War to the End of World War II. Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp.1–8

- ^Conway III, Lucian Gideon; Zubrod, Alivia; Chan, Linus; McFarland, James D.; Van de Vliert, Evert (8 February 2023)."Is the myth of left-wing authoritarianism itself a myth?".Frontiers in Psychology.13.doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1041391.ISSN1664-1078.PMC9944136.PMID36846476.

- ^Seidman, Michael.Transatlantic Antifascisms: From the Spanish Civil War to the End of World War II.Cambridge University Press, 2017, p. 252[ISBN missing]

- ^"Working Class Defence Organization, Anti-Fascist Resistance and the Arditi Del Popolo in Turin, 1919–22"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 19 March 2022.Retrieved23 September2021.

- ^Charles F. Delzell, edit.,Mediterranean Fascism 1919–1945,New York, NY, Walker and Company, 1971, p. 26

- ^"Working Class Defence Organization, Anti-Fascist Resistance and the Arditi Del Popolo in Turin, 1919–22"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 19 March 2022.Retrieved23 September2021.

- ^Working Class Defence Organization, Anti-Fascist Resistance and the Arditi Del Popolo in Turin, 1919–22Archived19 March 2022 at theWayback Machine,Antonio Sonnessa, in theEuropean History Quarterly,Vol. 33, No. 2, 183–218 (2003)

- ^"Anarchist Century".Anarchist_century.tripod.com.Retrieved7 April2014.

- ^Bruscino, Felicia (25 November 2017)."Il Popolo del 1925 col manifesto antifascista: ritrovata l'unica copia".Ultima Voce(in Italian).Retrieved23 March2022.

- ^James Martin, 'Piero Gobetti's Agonistic Liberalism',History of European Ideas,32,(2006), pp. 205–222.

- ^Pugliese, Stanislao G.; Pugliese, Stanislao (2004).Fascism, Anti-fascism, and the Resistance in Italy: 1919 to the Present.Rowman & Littlefield. p. 10.ISBN978-0-7425-3123-9.Retrieved11 June2020.

- ^Tollardo, Elisabetta (2016).Fascist Italy and the League of Nations, 1922-1935.Springer. p. 152.ISBN978-1-349-95028-7.

- ^Scala, Spencer M. Di (1988).Renewing Italian Socialism: Nenni to Craxi.Oxford University Press. pp. 6–8.ISBN978-0-19-536396-8.Retrieved11 June2020.

- ^abJames D. Wilkinson (1981).The Intellectual Resistance Movement in Europe.Harvard University Press. p. 224.

- ^Stanislao G. Pugliese (1999).Carlo Rosselli: socialist heretic and antifascist exile.Harvard University Press. p. 51.

- ^""Oggi in Spagna, domani in Italia""(in Italian).Retrieved12 May2023.

- ^Milica Kacin Wohinz,Jože Pirjevec,Storia degli sloveni in Italia: 1866–1998(Venice: Marsilio, 1998)

- ^Milica Kacin Wohinz,Narodnoobrambno gibanje primorskih Slovencev: 1921–1928(Trieste: Založništvo tržaškega tiska, 1977)

- ^Milica Kacin Wohinz,Prvi antifašizem v Evropi(Koper: Lipa, 1990)

- ^Mira Cenčič,TIGR: Slovenci pod Italijo in TIGR na okopih v boju za narodni obstoj(Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1997)

- ^Vid Vremec, Pinko Tomažič in drugi tržaški proces 1941 (Trieste: Založništvo tržaškega tiska, 1989)

- ^"Intelligence and Operational Support for the Anti-Nazi Resistance".Darbysrangers.tripod.com.

- ^"90 let od požiga Narodnega doma v Trstu"[90 Years From the Arson of the National Hall in Trieste].Primorski dnevnik [The Littoral Daily](in Slovenian). 2010. pp. 14–15.COBISS11683661.Archived fromthe originalon 14 October 2012.Retrieved28 February2012.

Požig Narodnega doma ali šentjernejska noč tržaških Slovencev in Slovanov [Arson of the National Hall or the St. Bartholomew's Night of the Triestine Slovenes and Slavs]

- ^Sestani, Armando, ed. (10 February 2012)."Il confine orientale: una terra, molti esodi"[The Eastern Border: One Land, Multiple Exoduses](PDF).I profugi istriani, dalmati e fiumani a Lucca[The Istrian, Dalmatian and Rijeka Refugees in Lucca] (in Italian). Instituto storico della Resistenca e dell'Età Contemporanea in Provincia di Lucca. pp. 12–13.[permanent dead link]

- ^Hehn, Paul N. (2005).A low dishonest decade: the great powers, Eastern Europe, and the economic origins of World War II, 1930–1941.Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 44–45.ISBN978-0-8264-1761-9.

- ^Cresciani, Gianfranco (2004)Clash of civilisationsArchived6 May 2020 at theWayback Machine,Italian Historical Society Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 4

- ^Jože Pirjevec, Milica Kacin-Wohinz: Zgodovina primorskih Slovencev (The history of the Slovenians living on the Coast), Nova revija, Ljubljana 2002

- ^Eve Rosenhaft,Beating the Fascists?: The German Communists and Political Violence 1929–1933,Cambridge University Press, 25 Aug 1983, pp. 3–4

- ^Heinrich August Winkler:Der Weg in die Katastrophe. Arbeiter und Arbeiterbewegung in der Weimarer Republik 1930–1933.Bonn 1990,ISBN3-8012-0095-7.

- ^Hoppe, Bert (2011).In Stalins Gefolgschaft: Moskau und die KPD 1928–1933.Oldenbourg Verlag.ISBN9783486711738.

- ^Stephan, Pieroth (1994).Parteien und Presse in Rheinland-Pfalz 1945–1971: ein Beitrag zur Mediengeschichte unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mainzer SPD-Zeitung 'Die Freiheit'.v. Hase & Koehler Verlag. p. 96.ISBN9783775813266.

- ^Braunthal, Julius (1963).Geschichte der Internationale: 1914–1943.Vol. 2, p. 414. Dietz.

- ^Siegfried Lokatis:Der rote Faden. Kommunistische Parteigeschichte und Zensur unter Walter Ulbricht.Böhlau Verlag, Köln 2003,ISBN3-412-04603-5(Zeithistorische Studienseries, vol. 25), p. 60

- ^Loren Balhorn"The Lost History of Antifa"Archived24 August 2017 at theWayback MachineJacobinMay 2017

- ^Friedmann, Sarah (15 August 2017)."This Is What The Antifa Flag Symbols Mean".Bustle.Retrieved16 April2019.

- ^Hobsbawm, Eric (17 February 2007)."The Spanish civil war united a generation of young writers, poets and artists in political fervour, says Eric Hobsbawm".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved5 June2020.

- ^Stevens, David R. (2008).Sin Perdón.AuthorHouse.ISBN978-1-4343-8094-4.

- ^The Literary Digest.Funk & Wagnalls. April 1929.

- ^De Miguel, Jesús y Sánchez, Antonio:Batalla de Madrid,in hisHistoria Ilustrada de la Guerra Civil Española.Alcobendas, Editorial Libsa, 2006, pp. 189–221.

- ^Boadilla byEsmond Romilly.The Clapton PressLimited, London. 2018.ISBN978-1999654306

- ^SeeWolf MoonbyJulio Llamazares,Peter Owen Publications, London 2017ISBN978-0720619454[page needed]

- ^Jacobs, Joe (1991) [1977].Out of the Ghetto.London: Phoenix Press.

- ^Phil PiratinOur Flag Stays Red.London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2006.

- ^Andrzej Olechnowicz, 'Liberal anti-fascism in the 1930s the case of Sir Ernest Barker',Albion36, 2005, pp. 636–660

- ^Tirabassi, Maddalena (1984–1985). "Enemy Aliens or Loyal Americans?: the Mazzini Society and the Italian-American Communities".Rivista di Studi Anglo-Americani(4–5): 399–425.

- ^Morrow, Felix(June 1943)."Washington's Plans for Italy".Fourth International.4(6): 175–179.Retrieved25 October2018.

- ^Premature antifascists and the Post-war worldArchived31 December 2013 at theWayback Machine,Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives Bill Susman Lecture Series. King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center atNew York University,1998. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^Knox, Bernard(Spring 1999). "Premature Anti-Fascist".Antioch Review.57(2): 133–149.doi:10.2307/4613837.JSTOR4613837.

- ^John Nichols (26 October 2009)."Clarence Kailin: 'Premature Antifascist' – and proudly so".Cap Times.Capital Times (Madision, Wisconsin).Retrieved29 December2013.

- ^Haynes, John Earl;Klehr, Harvey(2005).In Denial: Historians, Communism & Espionage.San Francisco: Encounter Books. p. 123.ISBN978-1594030888.Retrieved22 March2014.

- ^abOliver Hensengerth (2005).The Burmese Communist Party and the State-to-State Relations between China and Burma(PDF).Leeds East Asia Papers. pp. 10–12. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 28 May 2008.Retrieved23 September2020.

- ^abMartin Smith (1991).Burma – Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity.London and New Jersey: Zed Books. pp. 60–61.

- ^Haruhiro Fukui (1985)Political parties of Asia and the Pacific,Greenwood Press, pp. 108–109

- ^Gutman, Yisrael (1989).The Jews of Warsaw, 1939–1943: Ghetto, Underground, Revolt.Indiana University Press.ISBN978-0-253-20511-7.

- ^Kassow, Samuel D.(2007).Who Will Write Our History?: Emanuel Ringelblum, the Warsaw Ghetto, and the Oyneg Shabes Archive.Indiana University Press. p. 294.ISBN978-0-253-00003-3.

- ^Encyclopaedia Judaica.Vol. 16. Keter Publishing House. 1972. p. 349.

- ^Zuckerman, Yitzhak(1993). Harshav, Barbara (ed.).A Surplus of Memory: Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.University of California Press. p. 183.ISBN978-0-520-91259-5.

- ^Balhorn, Loren (8 May 2017)."The Lost History of Antifa".Jacobin.

- ^Mark Bray(2017). "'Never Again': The Development of Modern Antifa, 1945–2003". InAntifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook.Melville House Publishing. pp. 39–76.

- ^Defty, Brook (2007).Britain, America and Anti-Communist Propaganda 1945–1953.Chapters 2–5. The Information Research Department.

- ^Siegel, Achim (1998).The Totalitarian Paradigm after the End of Communism: Towards a Theoretical Reassessment.Rodopi. p. 200.ISBN9789042005525."Concepts of totalitarianism became most widespread at the height of the Cold War. Since the late 1940s, especially since the Korean War, they were condensed into a far-reaching, even hegemonic, ideology, by which the political elites of the Western world tried to explain and even to justify the Cold War constellation."[page needed]

- ^Guilhot, Nicholas (2005).The Democracy Makers: Human Rights and International Order.Columbia University Press. p. 33.ISBN9780231131247."The opposition between the West and Soviet totalitarianism was often presented as an opposition both moral and epistemological between truth and falsehood. The democratic, social, and economic credentials of the Soviet Union were typically seen as 'lies' and as the product of a deliberate and multiform propaganda. [...] In this context, the concept of totalitarianism was itself an asset. As it made possible the conversion of prewar anti-fascism into postwar anti-communism."

- ^Caute, David (2010).Politics and the Novel during the Cold War.Transaction Publishers. pp. 95–99.ISBN9781412831369.

- ^Reisch, George A. (2005).How the Cold War Transformed Philosophy of Science: To the Icy Slopes of Logic.Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–154.ISBN9780521546898.

- ^Beinart, Peter (16 August 2017)."What Trump Gets Wrong About Antifa".The Atlantic.Retrieved16 August2017.

- ^"The Lost History of Antifa".Jacobin Mag.15 August 2017.Retrieved5 December2014.

- ^Focus-Online."Demo-Samstag in Dresden: Nazi-Aufmärsche und Linke treffen aufeinander".Focus-Online.

- ^Bray, Mark(2017).Antifa: The Antifascist Handbook.Melville House Publishing. p. 54.ISBN9781612197043.

- ^Pfahl-Traughber, Armin(6 March 2008)."Antifaschismus als Thema linksextremistischer Agitation, Bündnispolitik und Ideologie"[Anti-fascism as a topic of far-left extremist agitation, political alliances and ideology].Federal Agency for Civic Education.

- ^ab"Aktionsfeld 'Antifaschismus'"[The field of "anti-fascism" ].Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution.Archived fromthe originalon 15 May 2020.Retrieved29 July2019.

Das Aktionsfeld "Antifaschismus" ist seit Jahren ein zentrales Element der politischen Arbeit von Linksextremisten, insbesondere aus dem gewaltorientierten Spektrum. [...] Die Aktivitäten von Linksextremisten in diesem Aktionsfeld zielen aber nur vordergründig auf die Bekämpfung rechtsextremistischer Bestrebungen. Im eigentlichen Fokus steht der Kampf gegen die freiheitliche demokratische Grundordnung, die als "kapitalistisches System" diffamiert wird, und deren angeblich immanente "faschistische" Wurzeln beseitigt werden sollen.

- ^abLinksextremismus: Erscheinungsformen und Gefährdungspotenziale[Far-left extremism: Manifestations and danger potential](PDF).Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution.2016. pp. 33–35. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2 June 2020.

Die Aktivitäten "antifaschistischer" Linksextremisten (Antifa) dienen indes nur vordergründig der Bekämpfung rechtsextremistischer Bestrebungen. Eigentliches Ziel bleibt der "bürgerlich-demokratische Staat", der in der Lesart von Linksextremisten den "Faschismus" als eine mögliche Herrschaftsform akzeptiert, fördert und ihn deshalb auch nicht ausreichend bekämpft. Letztlich, so wird argumentiert, wurzle der "Faschismus" in den gesellschaftlichen und politischen Strukturen des "Kapitalismus". Dementsprechend rücken Linksextremisten vor allem die Beseitigung des "kapitalistischen Systems" in den Mittelpunkt ihrer "antifaschistischen" Aktivitäten.

- ^"Linksextremismus" [Far-left extremism].Verfassungsschutzbericht 2018(PDF).Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community.2019. pp. 106–167. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2 September 2020.Retrieved21 October2020.

- ^Horst Schöppner:Antifa heißt Angriff: Militanter Antifaschismus in den 80er Jahren(pp. 129–132). Unrast, Münster 2015,ISBN3-89771-823-5.

- ^Newsroom (7 October 2020)."Δίκη Χρυσής Αυγής: Ένοχοι για εγκληματική οργάνωση Μιχαλολιάκος και πολιτικά στελέχη".CNN.gr(in Greek).Retrieved1 October2021.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^Maltezou, Renee; Papadimas, Lefteris (7 October 2020)."Greek court rules leaders of far-right Golden Dawn political party ran a crime group".National Post.Retrieved1 October2021.

- ^McGaw Smyth, Howard (September 1948). "Italy: From Fascism to the Republic (1943–1946)".The Western Political Quarterly.1(3): 205–222.doi:10.2307/442274.JSTOR442274.

- ^"Fondazione ISEC – cronologia dell'insurrezione a Milano – 25 aprile"(in Italian).Retrieved28 September2019.

- ^"Chi Siamo".Website.ANPI.it. Archived fromthe originalon 2 May 2011.Retrieved14 April2011.

- ^"RISCOPRIRE I VALORI DELLA RESISTENZA NELLA COSTITUZIONE"(in Italian).Retrieved22 October2022.

- ^"Festa dell'anpi".anpi.it. Archived fromthe originalon 24 May 2010.Retrieved22 October2022.

- ^"Bella ciao, significato e testo: perché la canzone della Resistenza non appartiene (solo) ai comunisti"(in Italian). 13 September 2022.Retrieved21 October2022.

- ^"ATENE – Comizio di chiusura di Alexis Tsipras".Archived fromthe originalon 20 April 2020.Retrieved23 January2015.

- ^"Non solo Tsipras:" Bella ciao "cantata in tutte le lingue del mondo Guarda il video – Corriere TV"[Not only Tsipras: "Bella ciao" sung in all languages of the world Watch the video – Corriere TV].video.corriere.it(in Italian).

- ^Stein, Perry (16 August 2017)."Anarchists and the antifa: The history of activists Trump condemns as the 'alt-left'".Chicago Tribune.Retrieved10 November2017.

- ^Snyders, Matt (20 February 2008)."Skinheads at Forty".City Pages.Archived fromthe originalon 3 August 2012.Retrieved29 July2012.

- ^Bray, Mark (16 August 2017)."Who are the antifa?".The Washington Post.ISSN0190-8286.Retrieved10 November2017.

- ^Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas (2 July 2019)."What Is Antifa? Explaining the Movement to Confront the Far Right".The New York Times.Retrieved13 July2019.

- ^abSacco, Lisa N. (9 June 2020)."Are Antifa Members Domestic Terrorists? Background on Antifa and Federal Classification of Their Actions InFocus IF10839".Congressional Research Service.Retrieved9 September2020.Updated June 9, 2020.

- ^Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas; Garcia, Sandra E. (28 September 2020)."What Is Antifa, the Movement Trump Wants to Declare a Terror Group?".The New York Times.Retrieved1 October2020.

One of the first groups in the United States to use the name was Rose City Antifa, which says it was founded in 2007 in Portland.

- ^"One America - Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment".The White House.Retrieved27 February2024.

- ^Enzinna, Wes (27 April 2017)."Inside the Underground Anti-Racist Movement That Brings the Fight to White Supremacists".Mother Jones.Retrieved9 September2020.

- ^Strickland, Patrick (21 February 2017)."US anti-fascists: 'We can make racists afraid again'".Al-Jazeera.Retrieved9 September2020.

- ^Lennard, Natasha (19 January 2017)."Anti-Fascists Will Fight Trump's Fascism in the Streets".The Nation.Archived fromthe originalon 15 August 2017.Retrieved9 September2020.

- ^Clarke, Colin; Kenney, Michael (23 June 2020)."What Antifa Is, What It Isn't, and Why It Matters".War on the Rocks.Retrieved26 June2020.

[...] Antifa, a highly decentralized movement of anti-racists who seek to combat neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and far-right extremists whom Antifa's followers consider 'fascist' [...].

- ^"Designating Antifa as Domestic Terrorist Organization Is Dangerous, Threatens Civil Liberties".Southern Poverty Law Center. 2 June 2020.Retrieved8 September2020.

- ^Kaste, Martin; Siegler, Kirk (16 June 2017)."Fact Check: Is Left-Wing Violence Rising?".NPR.org.NPR.Retrieved15 August2017.

- ^Maida, Adam (16 January 2018)."Meet Antifa's Secret Weapon Against Far-Right Extremists".Wired.Retrieved13 November2018.

- ^Beauchamp, Zack (8 June 2020)."Antifa, explained".Vox.Retrieved12 June2020.

- ^abLois, Beckett (27 July 2020)."Anti-fascists linked to zero murders in the US in 25 years".The Guardian.

- ^Jones, Seth G. (4 June 2020)."Who Are Antifa, and Are They a Threat?".Center for Strategic and International Studies.Retrieved4 September2020.

- ^Pasley, James."Trump frequently accuses the far-left of inciting violence, yet right-wing extremists have killed 329 victims in the last 25 years, while antifa members haven't killed any, according to a new study".Business Insider.Retrieved6 October2020.

- ^Swan, Betsy Woodruff(4 September 2020)."DHS draft document: White supremacists are greatest terror threat".Politico.Retrieved5 September2020.

- ^"A Fake Antifa Account Was 'Busted' for Tweeting from Russia".Vice News. 28 September 2017.Retrieved11 September2018.

- ^"Far-right smear campaign against Antifa exposed by Bellingcat".BBC. 24 August 2017.Retrieved20 July2022.

- ^Feldman, Brian (21 August 2017)."How to Spot a Fake Antifa Account".New York.Retrieved14 August2019.

- ^Glaun, Dan (14 September 2017)."Fake Boston Antifa group, which claimed credit for anti-racism banner at Red Sox game, is actually run by right wing trolls".The Republican.Retrieved14 August2019.

- ^Feuer, Alan; Goldman, Adam; MacFarquhar, Neil (11 June 2020)."Federal Arrests Show No Sign That Antifa Plotted Protests".The New York Times.Retrieved11 June2020.

Despite claims by President Trump and Attorney General William P. Barr, there is scant evidence that loosely organized anti-fascists are a significant player in protests. [...] A review of the arrests of dozens of people on federal charges reveals no known effort by antifa to perpetrate a coordinated campaign of violence. Some criminal complaints described vague, anti-government political leanings among suspects, but a majority of the violent acts that have taken place at protests have been attributed by federal prosecutors to individuals with no affiliation to any particular group.

- ^Peiser, Jaclyn (10 August 2020)."'Their tactics are fascistic': Barr slams Black Lives Matter, accuses the left of 'tearing down the system'".The Washington Post.Retrieved10 August2020.

- ^Haberman, Maggie; Savage, Charlie (31 May 2020)."Trump, Lacking Clear Authority, Says U.S. Will Declare Antifa a Terrorist Group".The New York Times.Retrieved13 June2020.

- ^Perez, Evan; Hoffman, Jason (31 May 2020)."Trump tweets Antifa will be labeled a terrorist organization but experts believe that's unconstitutional".CNN.CNN.Retrieved13 June2020.

- ^Bray, Mark (1 June 2020)."Antifa isn't the problem. Trump's bluster is a distraction from police violence".The Washington Post.Retrieved8 June2020.

- ^Dokumentation der Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ost-Mitteleuropa.Vol. 3. Bundesministerium für Vertriebene. 1953. p. 101.

- ^"Samtalskompassen – Våldsbejakande vänsterextremism: Ideologi".Samtalskompassen.samordnarenmotextremism.se.Archived fromthe originalon 24 August 2017.Retrieved24 August2017.

- ^Peters, Tim (2007).Der Antifaschismus der PDS aus antiextremistischer Sicht[The antifascism of the PDS from an anti-extremist perspective]. Springer. pp. 33–37, 186.ISBN9783531901268.

- ^Richter, Michael (2006). "Die doppelte Diktatur: Erfahrungen mit Diktatur in der DDR und Auswirkungen auf das Verhältnis zur Diktatur heute ("The double dictatorship: experiences with dictatorship in the GDR and effects on the relationship to the dictatorship today") ". In Besier, Gerhard; Stoklosa, Katarzyna (eds.).Lasten diktatorischer Vergangenheit – Herausforderungen demokratischer Gegenwart[Burdens of a dictatorial past – challenges of a democratic present]. LIT Verlag. pp. 195–208.ISBN9783825887896.Archived fromthe originalon 22 December 2021.Retrieved6 June2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Copsey, Nigel (2016).Anti-Fascism in Britain.Taylor & Francis.ISBN978-1-317-39762-5.

- Diner, Dan; Gundermann, Christian (1996). "On the Ideology of Antifascism".New German Critique(67): 123–132.doi:10.2307/827781.ISSN0094-033X.JSTOR827781.

- Eley, Geoff (1996). "Legacies of Antifascism: Constructing Democracy in Postwar Europe".New German Critique(67): 73–100.doi:10.2307/827778.ISSN0094-033X.JSTOR827778.

- Jarausch, Konrad H. (1991)."The Failure of East German Antifascism: Some Ironies of History as Politics".German Studies Review.14(1): 85–102.doi:10.2307/1430155.ISSN0149-7952.JSTOR1430155.

- Mammone, Andrea (2006)."A Daily Revision of the Past: Fascism, Anti-Fascism, and Memory in Contemporary Italy".Modern Italy.11(2): 211–226.doi:10.1080/13532940600709338.ISSN1353-2944.S2CID145602289.

- Rabinbach, Anson (1996). "Introduction: Legacies of Antifascism".New German Critique(67): 3–17.doi:10.2307/827774.ISSN0094-033X.JSTOR827774.

Further reading

[edit]- David Berry "'Fascism or Revolution!' Anarchism and Antifascism in France, 1933–39"Contemporary European HistoryVolume 8, Issue 1 March 1999, pp. 51–71

- Birchall, Sean, ed. (2013).Beating The Fascists: The Untold Story of Anti-Fascist Action.Freedom Press.ISBN978-1-904491-12-5.

- Brasken, Kasper. "Making Anti-Fascism Transnational: The Origins of Communist and Socialist Articulations of Resistance in Europe, 1923–1924."Contemporary European History25.4 (2016): 573–596.

- Bray, Mark (2017).Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook.New York: Melville House.ISBN978-1612197036.OCLC1016082358.

- Bullstreet, K. (2001).Bash the Fash: Anti-Fascist Recollections 1984–1993.Kate Sharpley Library.ISBN978-1-873605-87-5.

- Class War/3WayFight/Kate Sharpley LibraryInterview fromBeating Fascism: Anarchist Anti-Fascism in Theory and Practice,anarkismo.net

- Copsey, N. (2011) "From direct action to community action: The changing dynamics of anti-fascist opposition", inCopsey, Nigel (2011).The British National Party: contemporary perspectives.Abingdon, Oxon New York: Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-48384-1.OCLC657270952.

- Nigel Copsey & Andrzej Olechnowicz (eds.),Varieties of Anti-fascism. Britain in the Inter-war Period,Palgrave Macmillan

- Gilles Dauvé"Fascism/AntifascismArchived30 January 2010 at theWayback Machine",libcom.org

- David Featherstone "Black Internationalism, Subaltern Cosmopolitanism, and the Spatial Politics of Antifascism"Annals of the Association of American GeographersVolume 103, 2013, Issue 6, pp. 1406–1420

- Joseph Fronczak"Local People's Global Politics: A Transnational History of the Hands Off Ethiopia Movement of 1935"Diplomatic History,Volume 39, Issue 2, 1 April 2015, pp. 245–274

- Hugo Garcia, ed,Transnational Anti-Fascism: Agents, Networks, CirculationsContemporary European HistoryVolume 25, Issue 4 November 2016, pp. 563–572

- Key, Anna, ed. (2005).Beating Fascism: Anarchist anti-fascism in theory and practice.Kate Sharpley Library.ISBN978-1-873605-88-2.

- Renton, Dave.Fascism, Anti-fascism and Britain in the 1940s.Springer, 2016.

- Stout, James (24 June 2020)."A Brief History of Anti-Fascism".Smithsonian Magazine.Retrieved4 September2020.

- Enzo Traverso"Intellectuals and Anti-Fascism: For a Critical Historization"New Politics,vol. 9, no. 4 (new series), whole no. 36, Winter 2004

- When Hate Groups Come to Town: A Handbook of Effective Community Responses.Atlanta: Center for Democratic Renewal. 1992.ISBN978-1-881320-05-0.

External links

[edit]- Centre for fascist, anti-fascist and post-fascist studies– Teesside University (archived 24 August 2017)

- Remembering the Anarchist Resistance to fascism