Antiquarian

Anantiquarianorantiquary(fromLatinantiquarius'pertaining to ancient times') is anaficionadoor student ofantiquitiesor things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who studyhistorywith particular attention to ancientartifacts,archaeologicaland historicsites,or historicarchivesandmanuscripts.The essence ofantiquarianismis a focus on theempirical evidenceof the past, and is perhaps best encapsulated in the motto adopted by the 18th-century antiquarySir Richard Colt Hoare,"We speak from facts, not theory."

TheOxford English Dictionaryfirst cites "archaeologist"from 1824; this soon took over as the usual term for one major branch of antiquarian activity." Archaeology ", from 1607 onwards, initially meant what is now seen as"ancient history"generally, with the narrower modern sense first seen in 1837.

Today the term "antiquarian" is often used in a pejorative sense, to refer to an excessively narrow focus on factual historical trivia, to the exclusion of a sense of historical context or process. Few today would describe themselves as "antiquaries", but some institutions such as theSociety of Antiquaries of London(founded in 1707) retain their historic names. The term "antiquarian bookseller" remains current for dealers in more expensive old books.

History[edit]

Antiquarianism in ancient China[edit]

During theSong dynasty(960–1279), the scholarOuyang Xiu(1007–1072) analyzed alleged ancient artifacts bearing archaicinscriptions in bronze and stone,which he preserved in a collection of some 400rubbings.[1]Patricia Ebreywrites that Ouyang pioneered early ideas inepigraphy.[2]

TheKaogutu(Khảo cổ đồ) or "Illustrated Catalogue of Examined Antiquity" (preface dated 1092) compiled by Lü Dalin (Lữ đại lâm) (1046–1092) is one of the oldest knowncataloguesto systematically describe and classify ancient artifacts which were unearthed.[3]Another catalogue was theChong xiu Xuanhe bogutu(Trọng tu tuyên hòa bác cổ đồ) or "Revised Illustrated Catalogue of Xuanhe Profoundly Learned Antiquity" (compiled from 1111 to 1125), commissioned byEmperor Huizong of Song(r. 1100–1125), and also featured illustrations of some 840 vessels and rubbings.[1][3]

Interests in antiquarian studies of ancient inscriptions and artifacts waned after the Song dynasty, but were revived by earlyQing dynasty(1644–1912) scholars such asGu Yanwu(1613–1682) andYan Ruoju(1636–1704).[3]

Antiquarianism in ancient Rome[edit]

Inancient Rome,a strongsense of traditionalismmotivated an interest in studying and recording the "monuments" of the past; theAugustanhistorianLivyuses the Latinmonumentain the sense of "antiquarian matters."[4]Books on antiquarian topics covered such subjects as the origin of customs,religious rituals,andpolitical institutions;genealogy; topography and landmarks; andetymology.Annalsandhistoriesmight also include sections pertaining to these subjects, but annals are chronological in structure, andRoman histories,such as those of Livy andTacitus,are both chronological and offer an overarching narrative and interpretation of events. By contrast, antiquarian works as a literary form are organized by topic, and any narrative is short and illustrative, in the form ofanecdotes.

Major antiquarianLatin writerswith surviving works includeVarro,Pliny the Elder,Aulus Gellius,andMacrobius.The Roman emperorClaudiuspublished antiquarian works, none of which is extant. Some ofCicero's treatises, particularlyhis work on divination,show strong antiquarian interests, but their primary purpose is the exploration of philosophical questions. Roman-eraGreek writersalso dealt with antiquarian material, such asPlutarchin hisRoman Questions[5]and theDeipnosophistaeofAthenaeus.The aim of Latin antiquarian works is to collect a great number of possible explanations, with less emphasis on arriving at a truth than in compiling the evidence. The antiquarians are often used as sources by the ancient historians, and many antiquarian writers are known only through these citations.[6]

Medieval and early modern antiquarianism[edit]

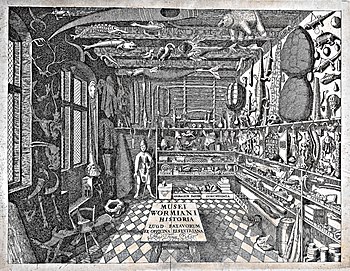

Despite the importance of antiquarian writing in theliterature of ancient Rome,some scholars view antiquarianism as emerging only in theMiddle Ages.[7]Medieval antiquarians sometimes made collections of inscriptions or records of monuments, but the Varro-inspired concept ofantiquitatesamong the Romans as the "systematic collections of all therelicsof the past "faded.[8]Antiquarianism's wider flowering is more generally associated with theRenaissance,and with the critical assessment and questioning ofclassicaltexts undertaken in that period byhumanistscholars. Textual criticism soon broadened into an awareness of the supplementary perspectives on the past which could be offered by the study ofcoins,inscriptionsand other archaeological remains, as well as documents from medieval periods. Antiquaries often formed collections of these and other objects;cabinet of curiositiesis a general term for early collections, which often encompassed antiquities and more recent art, items of natural history,memorabiliaand items from far-away lands.

The importance placed onlineageinearly modernEurope meant that antiquarianism was often closely associated withgenealogy,and a number of prominent antiquaries (includingRobert Glover,William Camden,William DugdaleandElias Ashmole) held office as professionalheralds.The development of genealogy as a "scientific"discipline (i.e. one that rejected unsubstantiated legends, and demanded high standards of proof for its claims) went hand-in-hand with the development of antiquarianism. Genealogical antiquaries recognised the evidential value for their researches of non-textual sources, includingsealsandchurch monuments.

Manyearly modernantiquaries were alsochorographers:that is to say, they recorded landscapes and monuments within regional or national descriptions. In England, some of the most important of these took the form ofcounty histories.

In the context of the 17th-centuryscientific revolution,and more specifically that of the "Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns"in England and France, the antiquaries were firmly on the side of the" Moderns ".[9]They increasingly argued that empiricalprimaryevidence could be used to refine and challenge the received interpretations of history handed down from literary authorities.

19th–21st centuries[edit]

By the end of the 19th century, antiquarianism had diverged into a number of more specialized academic disciplines includingarchaeology,art history,numismatics,sigillography,philology,literary studiesanddiplomatics.Antiquaries had always attracted a degree of ridicule (seebelow), and since the mid-19th century the term has tended to be used most commonly in negative or derogatory contexts. Nevertheless, many practising antiquaries continue to claim the title with pride. In recent years, in a scholarly environment in whichinterdisciplinarityis increasingly encouraged, many of the established antiquarian societies (seebelow) have found new roles as facilitators for collaboration between specialists.

Terminological distinctions[edit]

Antiquaries and antiquarians[edit]

"Antiquary" was the usual term in English from the 16th to the mid-18th centuries to describe a person interested in antiquities (the word "antiquarian" being generally found only in anadjectivalsense).[10]From the second half of the 18th century, however, "antiquarian" began to be used more widely as a noun,[11]and today both forms are equally acceptable.

Antiquaries and historians[edit]

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, a clear distinction was perceived to exist between the interests and activities of the antiquary and thehistorian.[9][12][13][14]The antiquary was concerned with the relics of the past (whetherdocuments,artefactsormonuments), whereas the historian was concerned with thenarrativeof the past, and its political or moral lessons for the present. The skills of the antiquary tended to be those of the critical examination and interrogation of his sources, whereas those of the historian were those of the philosophical and literary reinterpretation of received narratives. Jan Broadway defines an antiquary as "someone who studied the past on a thematic rather than a chronological basis".[15]Francis Baconin 1605 described readings of the past based on antiquities (which he defined as "Monuments, Names, Wordes, Proverbes, Traditions, Private Recordes, and Evidences, Fragments of stories, Passages of Bookes, that concerne not storie, and the like" ) as "unperfect Histories".[16]Such distinctions began to be eroded in the second half of the 19th century as the school ofempiricalsource-based history championed byLeopold von Rankebegan to find widespread acceptance, and today's historians employ the full range of techniques pioneered by the early antiquaries. Rosemary Sweet suggests that 18th-century antiquaries

... probably had more in common with the professional historian of the twenty-first century, in terms of methodology, approach to sources and the struggle to reconcile erudition with style, than did the authors of the grand narratives of national history.[17]

Antiquarians, antiquarian books and antiques[edit]

In many European languages, the word antiquarian (or its equivalent) has shifted in modern times to refer to a person who either trades in or collects rare and ancientantiquarian books;or who trades in or collectsantique objectsmore generally. In English, however, although the terms "antiquarian book" and "antiquarian bookseller" are widely used, the nouns "antiquarian" and "antiquary" very rarely carry this sense. An antiquarian is primarily astudentof ancient books, documents, artefacts or monuments. Many antiquarians have also built up extensive personalcollectionsin order to inform their studies, but a far greater number have not; and conversely many collectors of books or antiques would not regard themselves (or be regarded) as antiquarians.

Pejorative associations[edit]

Antiquaries often appeared to possess an unwholesome interest in death, decay, and the unfashionable, while their focus on obscure and arcane details meant that they seemed to lack an awareness both of the realities and practicalities of modern life, and of the wider currents of history. For all these reasons they frequently became objects of ridicule.[18][19][20]

The antiquary was satirised inJohn Earle'sMicro-cosmographieof 1628 ( "Hee is one that hath that unnaturall disease to bee enamour'd of old age, and wrinkles, and loves all things (as Dutchmen doe Cheese) the better for being mouldy and worme-eaten" ),[21]inJean-Siméon Chardin's paintingLe Singe Antiquaire(c. 1726), in SirWalter Scott's novelThe Antiquary(1816), in the caricatures ofThomas Rowlandson,and in many other places. TheNew Dictionary of the Terms Ancient and Modern of the Canting Crewofc. 1698defines an antiquary as "A curious critic in old Coins, Stones and Inscriptions, in Worm-eaten Records and ancient Manuscripts, also one that affects and blindly dotes, on Relics, Ruins, old Customs Phrases and Fashions".[22]In his "Epigrams",John Donnewrote of The Antiquary: "If in his study he hath so much care To hang all old strange things Let his wife beware." The word's resonances were close to those of modern terms for individuals with obsessive interests in technical minutiae, such asnerd,trainspotteroranorak.

TheconnoisseurHorace Walpole,who shared many of the antiquaries' interests, was nonetheless emphatic in his insistence that the study of cultural relics should be selective and informed bytasteandaesthetics.He deplored the more comprehensive and eclectic approach of the Society of Antiquaries, and their interest in the primitive past. In 1778 he wrote:

The antiquaries will be as ridiculous as they used to be; and since it is impossible to infuse taste into them, they will be as dry and dull as their predecessors. One may revive what perished, but it will perish again, if more life is not breathed into it than it enjoyed originally. Facts, dates and names will never please the multitude, unless there is some style and manner to recommend them, and unless some novelty is struck out from their appearance. The best merit of the Society lies in their prints; for their volumes, no mortal will ever touch them but an antiquary. Their Saxon and Danish discoveries are not worth more than monuments of theHottentots;and for Roman remains in Britain, they are upon a foot with what ideas we should get ofInigo Jones,if somebody was to publish views of huts and houses that our officers run up atSenegalandGoree.Bishop Lytteltonused to torment me with barrows and Roman camps, and I would as soon have attended to the turf graves in our churchyards. I have no curiosity to know how awkward and clumsy men have been in the dawn of arts or in their decay.[23]

In his essay "On the Uses and Abuses of History for Life" from hisUntimely Meditations,philosopherFriedrich Nietzscheexamines three forms ofhistory.One of these is "antiquarian history", an objectivising historicism which forges little or no creative connection between past and present. Nietzsche'sphilosophy of historyhad a significant impact oncritical historyin the 20th century.

C. R. Cheney,writing in 1956, observed that "[a]t the present day we have reached such a pass that the word 'antiquary' is not always held in high esteem, while 'antiquarianism' is almost a term of abuse".[24]Arnaldo Momiglianoin 1990 defined an antiquarian as "the type of man who is interested in historical facts without being interested in history".[25]Professional historians still often use the term "antiquarian" in a pejorative sense, to refer to historical studies which seem concerned only to place on record trivial or inconsequential facts, and which fail to consider the wider implications of these, or to formulate any kind of argument. The term is also sometimes applied to the activities of amateur historians such ashistorical reenactors,who may have a meticulous approach to reconstructing the costumes ormaterial cultureof past eras, but who are perceived to lack much understanding of the cultural values and historical contexts of the periods in question.

Antiquarian societies[edit]

London societies[edit]

ACollege (or Society) of Antiquarieswas founded in London inc. 1586,to debate matters of antiquarian interest. Members includedWilliam Camden,Sir Robert Cotton,John Stow,William Lambarde,Richard Carewand others. This body existed until 1604, when it fell under suspicion of being political in its aims, and was abolished by KingJames I.Papers read at their meetings are preserved inCotton's collections,and were printed byThomas Hearnein 1720 under the titleA Collection of Curious Discourses,a second edition appearing in 1771.[26]

In 1707 a number of English antiquaries began to hold regular meetings for the discussion of their hobby and in 1717 theSociety of Antiquarieswas formally reconstituted, finally receiving a charter from KingGeorge IIin 1751. In 1780 KingGeorge IIIgranted the society apartments inSomerset House,and in 1874 it moved into its present accommodation inBurlington House,Piccadilly. The society was governed by a council of twenty and a president who isex officioa trustee of theBritish Museum.[26]

Other notable societies[edit]

- TheSociety of Antiquaries of Scotlandwas founded in 1780 and had the management of a large national antiquarian museum inEdinburgh.[26]

- TheSociety of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne,the oldest provincial antiquarian society in England, was founded in 1813.

- InIrelanda society was founded in 1849 called the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, holding its meetings atKilkenny.In 1869 its name was changed to the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland, and in 1890 to theRoyal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland,its office being transferred toDublin.[26]

- InFrancetheSociété des Antiquaires de Francewas formed in 1813 by the reconstruction of theAcadêmie Celtique,which had existed since 1804.[26]

- TheAmerican Antiquarian Societywas founded in 1812, with its headquarters atWorcester,Massachusetts.[26]In modern times, its library has grown to over 4 million items,[27]and as an institution it is internationally recognized as a repository and research library for early (pre-1876) American printed materials.

- InDenmark,theKongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab(also known asLa Société Royale des Antiquaires du Nordor the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries) was founded atCopenhagenin 1825.

- InGermanytheGesamtverein der Deutschen Geschichts- und Altertumsvereinewas founded in 1852.[26]

In addition, a number of local historical and archaeological societies have adopted the word "antiquarian" in their titles. These have included theCambridge Antiquarian Society,founded in 1840; theLancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society,founded in 1883; theClifton Antiquarian Club,founded inBristolin 1884; theOrkney Antiquarian Society,founded in 1922; and thePlymouth Antiquarian Society,founded inPlymouth, Massachusettsin 1919.

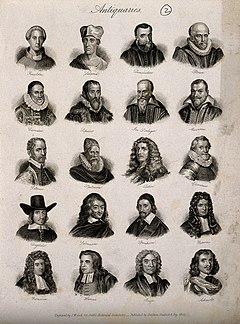

Notable antiquarians[edit]

See also[edit]

- Historian

- Collector

- Connoisseur

- Epigraphy

- Sigillography

- Nomenclature

- Typology (archaeology)

- Renaissance humanism

- English county histories

- Auxiliary sciences of history

- The Antiquaryby SirWalter Scott

- Cabinet of curiosities

References[edit]

- ^abClunas, Craig.(2004).Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China.Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.ISBN0-8248-2820-8.p. 95.

- ^Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999).The Cambridge Illustrated History of China.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-66991-X,p. 148.

- ^abcTrigger, Bruce G. (2006).A History of Archaeological Thought: Second Edition.New York: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-84076-7.p. 74.

- ^Livy,Ab Urbe Condita7.3.7: cited also in theOxford Latin Dictionary(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982, 1985 reprinting), p. 1132, entry onmonumentum,as an example of meaning 4b, "recorded tradition."

- ^AtLacusCurtius,Bill Thayer presents an edition of theRoman QuestionsArchived8 January 2023 at theWayback Machinebased on theLoeb Classical Librarytranslation. Thayer's edition can be browsed question-by-question in tabulated form, with direct links to individual topics.

- ^This overview of Roman antiquarianism is based onT.P. Wiseman,Clio's Cosmetics(Bristol: Phoenix Press, 2003, originally published 1979 by Leicester University Press), pp. 15–15, 45et passim;andA Companion to Latin Literature,edited by Stephen Harrison (Blackwell, 2005), pp. 37–38, 64, 77, 229, 242–244et passim.

- ^El Daly, Okasha (2004).Egyptology: The Missing Millennium: Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings.Routledge.p. 35.ISBN1-84472-063-2.

- ^Arnaldo Momigliano,"Ancient History and the Antiquarian,"Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes13 (1950), p. 289.

- ^abLevine,Battle of the Books.

- ^FirstOEDuses of "Antiquary. 3" 1586 and 1602.

- ^OED"Antiquarian" as noun, first uses 1610, then 1778

- ^Woolf, "Erudition and the Idea of History".

- ^Levine,Humanism and History,pp. 54–72.

- ^Levine,Amateur and Professional,pp. 28–30, 80–81.

- ^Broadway,"No Historie So Meete",p. 4.

- ^Bacon, Francis(2000) [1605]. Kiernan, Michael (ed.).The Advancement of Learning.Oxford Francis Bacon. Vol. 4. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 66.ISBN0-19-812348-5.

- ^Sweet,Antiquaries,p. xiv.

- ^B.S. Allen,Tides in English Taste (1619–1800),2 vols (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1937), vol. 2, pp. 87–92.

- ^Brown,Hobby-Horsical Antiquary,esp. pp. 13–17.

- ^Sweet,Antiquaries,pp. xiii, 4–5.

- ^John Earle, "An Antiquarie", inMicro-cosmographie(London, 1628), sigs [B8]v-C3v.

- ^B.E. (1699).A New Dictionary of the Terms Ancient and Modern of the Canting Crew.London. p. 16.

- ^Quoted in Martin Myrone, "The Society and Antiquaries and the graphic arts: George Vertue and his legacy", in Pearce 2007, p. 99.

- ^C.R. Cheney, "Introduction", in Levi Fox (ed.),English Historical Scholarship in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries(London, 1956), p. 4.

- ^Momigliano 1990, p. 54.

- ^abcdefgOne or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911). "Antiquary".Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 134.

- ^"Worcester's best kept secret: The American Antiquarian Society belongs to everyone | Worcester MagWorcester Mag".Archived fromthe originalon 17 October 2014.Retrieved10 October2014.Goslow, B. (2014, January 30). Worcester’s best kept secret: The American Antiquarian Society belongs to everyone. Worcester Magazine.

Bibliography[edit]

- Anderson, Benjamin; Rojas, Felipe, eds. (2017).Antiquarianisms: contact, conflict, comparison.Joukowsky Institute publication. Vol. 8. Oxford: Oxford Books.ISBN9781785706844.

- Broadway, Jan (2006)."No Historie So Meete": gentry culture and the development of local history in Elizabethan and early Stuart England.Manchester: Manchester University Press.ISBN978-0-7190-7294-9.

- Brown, I. G. (1980).The Hobby-Horsical Antiquary: a Scottish character, 1640–1830.Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland.ISBN0-902220-38-1.

- Fox, Levi,ed. (1956).English Historical Scholarship in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.London: Dugdale Society and Oxford University Press.

- Gransden, Antonia(1980). "Antiquarian Studies in Fifteenth-Century England".Antiquaries Journal.60:75–97.doi:10.1017/S0003581500035988.S2CID162807608.

- Kendrick, T. D.(1950).British Antiquity.London: Methuen.

- Levine, J. M. (1987).Humanism and History: origins of modern English historiography.Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.ISBN9780801418853.

- Levine, J. M. (1991).The Battle of the Books: history and literature in the Augustan age.Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.ISBN0801425379.

- Levine, Philippa (1986).The Amateur and the Professional: antiquarians, historians and archaeologists in Victorian England, 1838–1886.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-30635-3.

- Mendyk, S. A. E. (1989)."Speculum Britanniae": regional study, antiquarianism and science in Britain to 1700.Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Miller, Peter N.(2000).Peiresc's Europe: learning and virtue in the seventeenth century.New Haven: Yale University Press.ISBN0-300-08252-5.

- Miller, Peter N.(2017).History and Its Objects: antiquarianism and material culture since 1500.Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.ISBN9780801453700.

- Momigliano, Arnaldo(1950)."Ancient History and the Antiquarian".Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes.13(3/4): 285–315.doi:10.2307/750215.JSTOR750215.S2CID164918925.

- Momigliano, Arnaldo(1990). "The Rise of Antiquarian Research".The Classical Foundations of Modern Historiography.Berkeley: University of California Press. pp.54–79.ISBN0520068904.

- Parry, Graham (1995).The Trophies of Time: English antiquarians of the seventeenth century.Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN0198129629.

- Pearce, Susan, ed. (2007).Visions of Antiquity: The Society of Antiquaries of London 1707–2007.London: Society of Antiquaries.

- Piggott, Stuart(1976).Ruins in a Landscape: essays in antiquarianism.Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.ISBN0852243030.

- Stenhouse, William (2005).Reading Inscriptions and Writing Ancient History: historical scholarship in the late Renaissance.London: Institute of Classical Studies, University of London School of Advanced Study.ISBN0-900587-98-9.

- Suzuki, Hiroyuki (2022). Fukuoka, Maki (ed.).Antiquarians of Nineteenth-Century Japan: the archaeology of things in the late Tokugawa and early Meiji periods.Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute.ISBN9781606067420.

- Sweet, Rosemary (2004).Antiquaries: the discovery of the past in eighteenth-century Britain.London: Hambledon & London.ISBN1-85285-309-3.

- Vine, Angus (2010).In Defiance of Time: antiquarian writing in early modern England.Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-956619-8.

- Weiss, Roberto(1988).The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity(2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.ISBN9781597403771.

- Woolf, D. R.(1987). "Erudition and the Idea of History in Renaissance England".Renaissance Quarterly.40(1): 11–48.doi:10.2307/2861833.JSTOR2861833.S2CID164042832.

- Woolf, Daniel(2003).The Social Circulation of the Past: English historical culture, 1500–1730.Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-925778-7.