Archaeological ethics

Archaeological ethicsrefers to themoralissues raised through the study of the material past. It is a branch of thephilosophy of archaeology.This article will touch on human remains, the preservation and laws protecting remains and cultural items, issues around the globe, as well as preservation and ethnoarchaeology.

Archaeologists are bound to conduct their investigations to a high standard and observe intellectual property laws, health and safety regulations, and other legal obligations.[1]Archaeologists in the field are required to work towards the preservation and management of archaeological resources, treat human remains with dignity and respect, and encourageoutreachactivities. Sanctions are in place for those professionals who do not observe these ethical codes. Questions regarding archaeological ethics first began to arise during the 1960s and 1970s in North America and Western Europe.[2]AUNESCOratification to protect world culture in 1970 was one of the earliest actions to implement ethical standards.[2]Archaeologists conductingethnoarchaeologicalresearch, which involves the study of living people, are required to follow guidelines set by theNuremberg Code(1947) and theDeclaration of Helsinki(1964).[3]

History of ethics in archaeology[edit]

The earliestarchaeologistswere typically amateurs who would excavate a site with the sole purpose of collecting as many objects as they could for display in museums.[4]Curiosity about past humans and the potential for finding lucrative and fascinating objects justified what many professional archaeologists today would consider to be unethical archaeological behavior.[4]A shift toward scientific knowledge prompted many early archaeologists to begin documenting their finds. In 1906, theAntiquities Actcreated as the first act in America to help regulate archaeological discovery.[4]This act allowed for federal protection of sites from looting but failed to protect native peoples from having their land and ancestral objects seized.[4]TheSociety for American Archaeologywas developed in 1934.[4]This organization helped to bring regulation into the field ofarchaeologyand provided consistent training for professional archaeologists.[4]A series of laws passed in the 1960s and 1970s created the field ofcultural resource managementwhich protectsarchaeological sitesfrom encroaching development.[4]Debates about the rights of native peoples to their ancestral belongings occurred throughout the 1980s culminating in the passing of theNative American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.[4]The rise of ethics in archaeology was spurred by a shift inarchaeological theorytowardspost-processualismwhich focuses on critical evaluation of methods and the implications of archaeology on politics.[4]

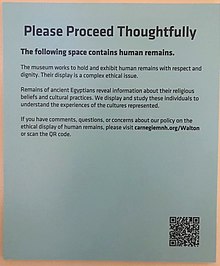

Human remains[edit]

A common ethical issue inmodern archaeologyhas been the treatment of human remains found duringexcavations,[5]especially those that represent the ancestors ofaboriginalgroups in theNew Worldor the remains of other minority races elsewhere.[6]In November 1990 the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was enacted, facilitating the return of certain human remains and sacred objects to lineal descendants and Native American Tribes.[7]Where previously sites of great significance to indigenous peoples could be excavated and burials andartifactstaken to be stored in museums or sold,[8]there is now increasing awareness of taking a more respectful approach. Technical developments in ancient DNA testing have raised more ethical questions in relation to the treatment of these human remains.[9]The issue is not limited to indigenous human remains. Nineteenth and twentieth century burial sites investigated by archaeologists, such asFirst World Wargraves disturbed by developments, have seen the remains of people with closely connected living relatives being exhumed and taken away.

Ethics in commercial archaeology[edit]

In the United States, the bulk of modern archaeological work is done under the auspices of development bycultural resource managementarchaeologists[11]in compliance with Section 106[12]of theNational Historic Preservation Act.Guidance for compliance with Section 106 is provided byThe Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.[12]

Impacts of nondisclosure agreements[edit]

Much of this work is subject tonon-disclosure agreementswith private entities. A primary ethical criticism levied against commercial archaeological practices is the prevalence of non-disclosure agreements associated with development projects involving a cultural resource management component.[13]Critics claim that NDA's are a barrier to public access to the archaeological record and create an unethical working condition for archaeologists to practice and that archaeology applied to the industry of development is itself a threat to the archaeological record.[13]This practice prohibits information gathered from the archaeological record during such projects from being disseminated to the public or academic institutions for further study and peer review. Scarre writes that "collecting items that are surplus to requirements…is academically pointless and morally irresponsible"[14]and it has been interpreted that data collected as a result of cultural resource management fieldwork unavailable to the public through NDA access restrictions creates such a surplus and therefore is ethically problematic.[13]

Private property and development[edit]

The issue of ownership is paramount in the ethical discussion regarding commercial archaeology. In most circumstances, with the exception of human remains and artifacts associated with burials, ownership of artifacts and other material recovered from archaeological investigations performed within the scope of development projects falls to the owner of the property on which the excavation is performed.[13]Many archaeologists consider this to be ethically problematic and a significant barrier to public access.

Colonization and conflict[edit]

TheWorld Archaeological Congresshas determined that "It is unethical for Professional Archaeologists and academic institutions to conduct professional archaeological work and excavations in occupied areas possessed by force".[15]This resolution has been interpreted to include not only regions where there is active military conflict but regions who have been in conflict in the past and are currently undercolonial rule,[13]for example, North and South America

Antiquities trade[edit]

Although not formally connected with the modern discipline of archaeology, the international trade inantiquitieshas also raised ethical questions regarding the ownership of archaeological artifacts. The market for imported antiquities has encouraged damage to archaeological sites and often led to appeals for the recall.[16]Famous sites such asAngkor Watin Cambodia have experienced problems with looting.[17]Looting often leads to loss of information as material remains are removed from their original contexts.[16]Examples of archaeological material which has been removed from its place of origin and over which there is now controversy regarding its return include theElgin Marbles.

In the United States, theAntiquities Actprotects archaeological material from looting.[1]The act establishes punishments forarchaeological lootingon federal land, allows the US president to declare archaeological sites as national monuments, establishes the government's duty to preserve archaeological sites and make them available for the public, and requires that Archaeology|archaeologists conducting research must meet the guidelines set by the Secretary of the Interior.[1]

Laws and protections around the world[edit]

Globally[edit]

TheWorld Archaeological Congress(WAC) is a global organization that holds a congress every four years to discuss recent publications and research as well as to update archaeological practice guidelines and policies.[18]TheWACpublishes a code of ethics for their archaeologists to follow.[18]Some of the accords which have been adopted by theWACcode of ethics include the Dead Sea Accord, theVermillion Accord on Human Remains,and the Tamaki Makau-rau Accord on the Display of Human Remains and Sacred Objects.[18]TheWAChas also published a separate code of ethics for the protection of the Amazon Forest Peoples.[18]In 1970, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization,UNESCO,held a convention in Paris on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.[19][20]Many countries joined and it was put into use in 1972.[21]It is important to note that archaeological ethics are not the same around the world and what is considered ethical behavior can vary from culture to culture.[4]Many archaeological organizations around the world require their members to follow a code of ethics; several of these associations, however, do not publish their code of ethics for non-members. Some of these associations include theKorean Archaeological Societyand theJapanese Archaeological Association.

The Register of Professional Archaeologists[22]is a multinational organization that provides accreditation for archaeologists and adjacent professionals. They provide a network which serves to connect archaeologists to each other and to industries which rely upon their expertise.

America[edit]

TheSociety for American Archaeology(SAA) is an organization which is dedicated the ethical practice of archaeology and the preservation of archaeological materials in America.[23]The SAA's committee on archaeological ethics continually updates the living document titled Principles of Archaeological Ethics, which was first created in 1966.[23]The SAA registers professional archaeologists who must agree to uphold the code of conduct while conducting research.[23]

The United States government continually passeslegislationto protect archaeological materials and uphold ethical archaeological research. TheAntiquities Act of 1906established punishment for archaeological looting, ensured the governments' responsibility to preserve archaeological sites, and created guidelines for conducting archaeological research.[1]The Historic Sites Act of 1935 further confirmed that the preservation of archaeological sites is of national concern.[1]TheNational Historic Preservation Act of 1966provided federal protection of archaeological sites and established the need for environmental review, ensuring that development does not destroy archaeological material.[1]TheArchaeological Resource Protection Act of 1979states that archaeological materials must be preserved once they are discovered.[1]TheNative American Graves Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA)constitutes that museums receiving government funding must attempt to return archaeological materials to Native Americans if the natives claim the material.[1]NAGPRAalso states that native organizations must be consulted when Native American materials are found or are expected to be found.[1]

Europe[edit]

TheEuropean Association of Archaeologists(EAA), like the Society for American Archaeology in the United States, is an organization which regulates the ethical practice of archaeology across Europe.[24]The EAA requires its members to follow a published code of ethics.[24]The code of ethics requires archaeologists to inform the public of their work, preserve archaeological sites, and evaluate the social and ecological impacts of their work before beginning.[24]This code further provides an ethical framework for conducting contractual archaeology, fieldwork training, and journal publications.[24]

While the EAA regulates ethical archaeological practices across Europe, the British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology further provides an ethical guideline for British archaeologists who are conducting research with human remains.[25]

Australia[edit]

TheAustralian Archaeological Association(AAA) is an organization which regulates and promotes archaeology across Australia.[26]The AAA has a published code of ethics which its members must follow.[26]The AAA code of ethics highlights issues such as gaininginformed consent,rights of indigenous people, and conservation of heritage sites.[26]The AAA code of ethics also states that any member who fails to adhere to the code is subject to disciplinary action.[26]

Canada[edit]

TheCanadian Archaeological Association(CAA) exists to promote archaeological knowledge, promote general interest in archaeology, and to act as a liaison between CanadianAboriginalsand archaeologists studying their ancestors.[27]The CAA assures ethical archaeological practices among their members by offering a principles of ethics guideline.[27]These principles of ethics focuses on assuring access to knowledge, conserving archaeological sites whenever possible, and promoting ethical relationships betweenAboriginalsand archaeologists.[27]

National and international controversies[edit]

Many archaeologists in the West today are employees of national governments or are privately employed instruments of government-derived archaeology legislation. In all cases this legislation is a compromise to some degree or another between the interests of the archaeological remains and the interests of economic development.

Germany[edit]

A question of control and ownership over the past has also been raised through the political manipulation of thearchaeological recordto promotenationalismand justify military invasion. A famous example is the corps of archaeologists employed byAdolf Hitlerto excavate in central Europe in the hope of finding evidence for a region-wideAryanculture.

United Kingdom[edit]

Questions regarding the ethical validity of government heritage policies and whether they sufficiently protect important remains are raised during cases such asHigh Speed 1inLondonwhere burials at a cemetery atSt Pancras railway stationwere hurriedly dug using aJCBand mistreated in order to keep an important infrastructure project on schedule.[28]

Greece[edit]

The Parthenon marbles, also known as theElgin Marbles,include a series of stone sculptures and friezes that were from theParthenonin Athens, Greece. Greece was under Ottoman rule at the time when Thomas Bruce, 7th Lord of Elgin, or Lord Elgin, as British Ambassador to theOttoman Empireasked that he be able to take some of the marbles to a safer place and was granted that in 1801. They were sold in 1816 to theBritish Museum,and Parliament paid £350,000 for the marbles. Greece has been petitioning to have the marbles returned since 1924, claiming that they were illegally obtained since they were occupied by a foreign force and were not acting in line with the people of Greece.[29][30][31]

Italy[edit]

In 1972, theMetropolitan Museum of Artin New York City purchased theEuphronious Krater,a vase used for mixing wine and water from a collector named Robert Hecht for $1,000,000. Hecht provided documentation which after Italian investigations proved to be falsified. This falsification was later confirmed in 2001 when authorities found a handwritten memoir of Hecht's. The Krater had been obtained in an illegal excavation in 1971, likely from an Etruscan tomb. It was purchased from theGiacomo Medicithen smuggled into Switzerland and sold to the museum in New York. In 2006, the museum's director,Philipe de Montebello,agreed to return the Krater along with several other items to Italy. They arrived back in Italy in 2008, and are on display at theVilla Giuliain Rome.[32][33]

Preservation[edit]

Another issue is the question of whether unthreatened archaeological remains should be excavated (and therefore destroyed) or preserved intact for future generations to investigate with potentially less invasive technology. Some archaeological guidance such asPPG 16has established a strong ethical argument for only excavating sites threatened with destruction. New technology such as laser scanning has pioneered non-invasive techniques for recording petroglyphs and engravings. Other technology like GPS and Google Earth has revolutionized the way archaeologists find and record potential archaeological sites.[16]

In the United States, several acts have been passed to help preserve archaeological sites.[1]Some of these acts include theNational Historic Preservation act of 1966,which allows for archaeological sites and materials of historical significance to be placed under federal protection, and theArchaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA) of 1979,which places all archaeological sites under federal protection, not just sites of historical significance.[1]

Cultural resource managementis a branch of archaeology which attempts to protect archaeological sites from development and construction damage.[34]

Ethics in ethnoarchaeology[edit]

Ethnoarchaeologyis the ethnographic study of people from an archaeological point of view. These studies are typically conducted on material remains from the society in question,[35]is sometimes used in conjunction with traditional archaeology. Ethnoarchaeology presents a unique case, because it deals with the study of people, which is heavily regulated.[36]Any research dealing with humans must be submitted to an ethics committee for approval under the Nuremberg Code (1947) and theDeclaration of Helsinki(1964).[1]Researchers must also obtaininformed consentfrom their research subjects.[1]

Archaeologists conducting ethnoarchaeology or other types of research involving humans must adhere to a certain code in order to conduct legal and ethical research, however, this code is the same that is followed bymedical research.There is no specific code for archaeological research involving humans.[1]This has been problematic and some archaeologists resist following amedical ethicscode by claiming thatmedical researchandethnographicresearch are too different to follow the same code.[1]

External links[edit]

- The Code of Ethics of the Archaeological Institute of America

- Institute of Field Archaeologists Code of Conduct

- Ethics and archaeology

- Archeology Law and Ethicsfrom theNational Park Service Archeology Program

- Society for American Archaeology

- British Sociological Association

- Social Anthropology of the UK and the Commonwealth

- The Economic and Social Research Council

References[edit]

- ^abcdefghijklmno"NPS Archeology Program: Archeology Law and Ethics".nps.gov.Retrieved2020-07-31.

- ^abGalor, Katharina (2017),"Archaeological Ethics",Finding Jerusalem,Archaeology between Science and Ideology, University of California Press, pp. 100–116,JSTOR10.1525/j.ctt1pq349g.13,retrieved2020-07-31

- ^Parker, Michael (2007-12-01)."Ethnography/ethics".Social Science & Medicine.Informed Consent in a Changing Environment.65(11): 2248–2259.doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.003.ISSN0277-9536.PMID17854966.

- ^abcdefghijChadwick, Ruth (2012).Encyclopedia of Applied Ethics.Elsevier. pp. 179–188.

- ^Squires, Kirsty; Errickson, David; Marquez-Grant, Nicholas (2020).Ethical approaches to human remains: a global challenge in bioarchaeology and forensic anthropology.Cham: Springer.ISBN978-3-030-32925-9.

- ^Mar 2017, Michael Balter / 30 (2017-03-30)."The Ethical Battle Over Ancient DNA".SAPIENS.Retrieved2020-07-12.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^"Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (U.S. National Park Service)".nps.gov.Retrieved2020-07-12.

- ^Fforde, Cressida (2003-08-27). Fforde, Cressida; Hubert, Jane; Turnbull, Paul (eds.).The Dead and their Possessions.doi:10.4324/9780203165775.ISBN9781134568376.

- ^Nicholas, George P. (2005)."Editor's Notes: On mtDNA and Archaeological Ethics".Canadian Journal of Archaeology.29(1): iii–vi.ISSN0705-2006.JSTOR41103512.

- ^"Carnegie Museum hiding famous 'Lion Attacking a Dromedary' diorama from view | TribLIVE.com".triblive.com.17 September 2020.Retrieved2020-11-02.

- ^"Archaeology as a Career".Society for American Archaeology.Retrieved2020-11-01.

- ^ab"Section 106 Regulations | Advisory Council on Historic Preservation".www.achp.gov.Retrieved2020-11-01.

- ^abcdeHutchings, Rich; La Salle, Marina (2015-12-01)."Archaeology as Disaster Capitalism".International Journal of Historical Archaeology.19(4): 699–720.doi:10.1007/s10761-015-0308-3.ISSN1573-7748.S2CID142960882.

- ^Scarre, Geoffrey (13 October 2014).Cultural Heritage Ethics: Between Theory and Practice.Open Book Publishers.ISBN978-1-78374-067-3.

- ^"FAQ – World Archaeological Congress".Retrieved2020-11-01.

- ^abcBahn, Paul (2013).Archaeology: A Very Short Introduction (2nd ed).Oxford University Press. pp. 107–108.ISBN9780199657438.

- ^Perlez, Jane (2005-03-21)."A Cruel Race to Loot the Splendor That Was Angkor".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Retrieved2020-07-31.

- ^abcd"Code of Ethics – World Archaeological Congress".Retrieved2020-10-30.

- ^"Fight Illicit Trafficking, Return & Restitution of Cultural Property".Unesco.org.2019.RetrievedOctober 20,2020.

- ^"Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property".portal.unesco.org.Retrieved2020-10-20.

- ^"Conventions".pax.unesco.org.Retrieved2020-10-20.

- ^"Register of Professional Archaeologists - Home".rpanet.org.Retrieved2020-11-01.

- ^abc"Home".Society for American Archaeology.Retrieved2020-10-07.

- ^abcd"EAA Codes".www.e-a-a.org.Retrieved2020-10-30.

- ^"Ethics and Standards - BABAO".www.babao.org.uk.Retrieved2020-10-30.

- ^abcd"Code of Ethics | Australian Archaeological Association | AAA".australianarchaeologicalassociation.com.au.Retrieved2020-10-30.

- ^abc"Principles of Ethical Conduct | Canadian Archaeological Association / Association canadienne d'archéologie".canadianarchaeology.com.Retrieved2020-10-30.

- ^Mead, Rebecca (16 February 2020)."The Bodies Buried Beneath Boris Johnson's New Railway".The New Yorker.Retrieved2020-07-31.

- ^"How did the Elgin Marbles get here?".BBC News.2014-12-05.Retrieved2020-10-20.

- ^"Elgin Marbles | Greek sculpture".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2020-10-20.

- ^"What's in a title? It's time to reframe the Parthenon Marbles debate".www.theartnewspaper.com.22 March 2019.Retrieved2020-10-20.

- ^"Euphronios (Sarpedon) Krater".Trafficking Culture.Retrieved2020-10-27.

- ^"Top 10 Plundered Artifacts".Time.2009-03-05.ISSN0040-781X.Retrieved2020-10-27.

- ^"ASC: What is Cultural Resource Management?".web.sonoma.edu.Retrieved2020-11-11.

- ^"Ethnoarchaeology".obo.Retrieved2020-09-29.

- ^"Human Research Protection".apa.org.Retrieved2020-09-29.