Architecture of Egypt

There have been many architectural styles used in Egyptian buildings over the centuries, includingAncient Egyptian architecture,Greco-Roman architecture,Islamic architecture,andmodern architecture.

Ancient Egyptian architecture is best known for its monumentaltemplesand tombs built in stone, including its famouspyramids,such as thepyramids of Giza.These were built with a distinctive repertoire of elements includingpylon gateways,hypostylehalls,obelisks,andhieroglyphicdecoration. The advent of GreekPtolemaic rule,followed byRoman rule,introduced elements of Greco-Roman architecture into Egypt, especially in the capital city ofAlexandria.After this cameCoptic architecture,includingearly Christian architecture,which continued to follow ancient classical andByzantineinfluences.

Following theMuslim conquest of Egyptin the 7th century, Islamic architecture flourished. A new capital,Fustat,was founded; it became the center of monumental architectural patronage thenceforth, and through successive new administrative capitals, it eventually became the modern city ofCairo.Early Islamic architecture displayed a mix of influences, including classical antiquity and new influences from the east such as theAbbasid stylethat radiated from theAbbasid Caliphate's heartland inMesopotomia(present-dayIraq) during the 9th century. In the 10th century, Egypt became the center of a new empire, theFatimid Caliphate.Fatimid architectureinitiated further developments that influenced the architectural styles of subsequent periods.Saladin,who overthrew the Fatimids and founded theAyyubid dynastyin the 12th century, was responsible for constructing theCairo Citadel,which remained the center of government until the 19th century. During theMamluk period(13th–16th centuries), a wealth of monumental religious and funerary complexes were built, constituting much of Cairo's medieval heritage today. TheMamluk architectural stylecontinued to linger even after theOttoman conquest of 1517,when Egypt became anOttoman province.

In the early 19th century,Muhammad Alibegan to modernize Egyptian society and encouraged a break with traditional medieval architectural traditions, initially by emulating lateOttoman architecturaltrends. Under the reign of his grandsonIsma'il Pasha(1860s and 1870s), reform efforts were pushed further, theSuez Canalwas constructed (inaugurated in 1869), and a newHaussmann-influenced expansion of Cairo began. European tastes became strongly evident in architecture in the late 19th century, though there was also a trend of reviving what were seen as indigenous or "national" architectural styles, seen in the many "neo-Mamluk" buildings of this era. In the 20th century, some Egyptian architects pushed back against dominant Western ideas of architecture. Among them,Hassan Fathywas known for adapting indigenous vernacular architecture to modern needs. Since then, Egypt continues to see new buildings erected in a variety of styles and for various purposes, ranging from housing projects to more monumental prestige projects like theCairo Tower(1961) and theBibliotheca Alexandrina(2002).

Ancient[edit]

Ancient Pharaonic period[edit]

Ancient Egypt's architecture includedpyramids,temples,enclosed cities, canals, and dams. Most buildings were built of locally available materials by paid laborers and craftsmen.[3][4][5][6]Monumental temples and tombs, built in stone and typically on terrain beyond the reach of the annual Nile floods, are the main structures to have survived to the present day.[7][8]The most common type of stone used throughout the country waslimestone,withsandstonealso commonly used and quarried further south.[9][10][11]Where harder stone was needed,granitewas widely employed,[9]withbasaltalso used for pavements.[11]

Monumental complexes were usually fronted by massivepylons,approached via processional avenues (also known as adromos) flanked bysphinxstatues, and contained courtyards andhypostylehalls.[12]Columns were typically adorned withcapitalsdecorated to resemble plants important to Egyptian civilization, such as thepapyrus plant,thelotus,orpalm.[7][12]Obeliskswere another characteristic feature. Walls were decorated with scenes andhieroglyphictexts either painted or incised inrelief.[13][7]

The first great era of construction took place during theOld Kingdom(c. 2700– c. 2200 BC), which is also when the most impressive pyramid tombs were built. The oldest monumental stone structure of Egypt is theStepped Pyramid of DjoseratSaqqara(c. 2650 BC), while theGreat Pyramids of Gizaand theGreat Sphinxwere all built roughly from 2600 to 2500 BC.[13][3]

The construction of great buildings was revived during theNew Kingdom(c. 1570– c. 1085 BC), whenThebesserved as the main capital. The most impressive monuments from this period include the great temple complex ofKarnak,theMortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut,theLuxor Temple,theTemple of Abu Simbel,theRamesseum(funerary temple ofRamses II) and theMortuary Temple of Ramses IIIatMedinet Habu.[13]Starting with theEighteenth Dynasty,the pharaohs were buried in underground tombs, richly-decorated but hidden from sight, in theValley of the Kings.[15]

Domestic architecture was typically built withmudbrick,wood, andreed mats,and the main towns were situated on the agriculturally rich floodplains of the Nile. As a result, little of this everyday architecture has survived.[7][8]Some idea of their form is known thanks to three-dimensional models that were left in tombs, which suggest that they resembled vernacular building types still found in the Nile valley and other parts of Africa today.[16]

Greco-Roman period[edit]

During theGreco-Roman periodof Egypt (332 BC–395 AD),[12]when Egypt was ruled by the GreekPtolemaic dynastyand then theRoman Empire,Egyptian architecture underwent significant changes due to the influence ofGreek architecture.[18][7]

The capital city ofAlexandriawas an innovator in architecture[how?]and its influence was felt in places such asPompeiiandConstantinople.[19]Its plan was largely that of a Greek city, with local elements mixed in.[18]Most of the city has disappeared under the water or under the modern city today, but it was known from descriptions to contain many great buildings including a royal palace, theMusaeum,theLibrary of Alexandria,and the famousPharos Lighthouse.[13]

Many well-preserved temples inUpper Egyptdate from this era, such as theTemple of Edfu,theTemple of Kom Ombo,and thePhilae temple complex.[7]While temple architecture remained more traditionally Egyptian, new Greco-Roman influences are evident, such as the appearance ofComposite capitals.[7][18]Egyptian motifs also made their way into wider Greek andRoman architecture.[12]

Much of the period's funerary architecture has not survived,[7]though some of Alexandria's underground catacombs, shared by the city's inhabitants to bury their dead, have been preserved. They feature a hybrid architectural style in which both classical and Egyptian decoration are mixed together. TheCatacombs of Kom El Shoqafa,begun in the 1st century AD and continuously enlarged until the 3rd century, are one notable example and can be visited today.[20]

Late Antiquity and Byzantine period[edit]

Coptic architecture,which dates from theLate AntiqueorByzantineperiod, is continuous with classical traditions.[18]Egypt was also the site of the earliest Christian monasteries,[22]which became numerous by the end of the 4th century AD.[23]Almost no traces of Alexandria's ancient churches have been found,[18]but some exceptional examples ofEarly Christian architecturehave been preserved in the Nile Valley, such as theRed Monastery(founded in the 4th century)[21]: 11 and theWhite Monastery(c. 440)[22]nearSohag.The continuity between earlier classical and later Coptic architecture can also be seen in the remains of major urban centres such asHermopolis Magna,where the same craftsmanship appears in both pagan and Christian buildings from the 3rd or 4th centuries.[24]At theKharga Oasisin theWestern Desert,theEl Bagawatnecropolis contains tombs and small chapels from both the pre-Christian and early Christian periods, ranging roughly from the late 3rd to 8th centuries.[25]The Chapel of the Exodus is one of the oldest at this site,[26]built around the early 4th century,[25]while a nearby church, possibly dating to the 5th century, may be one of the oldest remains of a church in Egypt.[26]

Remains of churches from the 4th and early 5th centuries show that they were built asbasilicaswith a tripartitesanctuaryincluding a transverse aisle and a straight eastern wall.[24]The Red Monastery and White Monastery at Sohag, representative of the 5th century, have rectangular basilical layouts culminating in a more sophisticatedtriconchsanctuary, surrounded by three semi-circularapseswith decorative niches.[27]By the 7th century, the typical plan of a Coptic church consisted of a basilica with abarrel-vaultednave, pillars and aisles along the sides and a transept flanked by three squareapsescovered by domes orsemi-domes.[22]Coptic churches continued to be built during the following Islamic period, usually retaining a basilical plan.[22]

Early Coptic buildings also demonstrate a continuing tradition of rich decoration, includingCorinthianand Byzantine "basket" capitals[22]and wall paintings.[28]Extensive remains of painted decoration, some of it in earlyByzantine style,can be found in the chapels of the Bagawat Necropolis – particularly in the Chapel of Peace from the 5th to 6th centuries and, in less sophisticated form, in the 4th-century Chapel of the Exodus[26]– and in the triconch of the Red Monastery – painted in various phases from the 5th to 13th centuries.[21]Many other examples of painted and sculptural decoration from ancient churches are preserved today at theCoptic Museumin Cairo.[29][30]

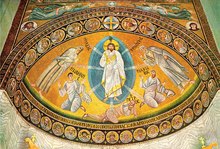

AtMount Sinai,theMonastery of Saint Catherine(originally dedicated to and named after theBurning Bush[31]) was built by emperorJustinian(r. 527–565).[32]Today it is the oldest continuously inhabited Christian monastery in the world.[33][34]Although much rebuilt and restored,[35]the site still retains substantial remains from its sixth-century construction,[32]including a three-aisled basilical church with aByzantine mosaicof theTransfiguration.[31][35]

Medieval[edit]

After theMuslim conquest of Egyptin 640, the region was initially integrated into theRashidun Caliphate,followed by theUmayyad CaliphateandAbbasid Caliphate.It was then ruled by a succession of autonomous local dynasties and later became the center of several Muslim empires. EarlyIslamic architecturein Egypt continued to be influenced by Late Antique traditions and soon afterwards byAbbasid architecturein contemporary Iraq (Mesopotamia).[36]Some Islamic-era buildings also reused materials fromPharaonicandByzantineeras, and in some later cases fromCrusaderbuildings in theLevant.[37]The greatest architectural patronage of the Islamic period was centered in Cairo,[38]which preserves one of the richest concentrations of medieval monuments in the Muslim world today.[39]

Early Islamic period[edit]

After the conquest of 640, the Arab conquerors established a new city calledFustat,near the former Byzantine-Roman fort ofBabylon,to serve as the administrative capital and military garrison center of Muslim Egypt. Later foundations near this initial urban center eventually transformed it into the modern city of Cairo.[40]The foundation of Fustat was also accompanied by the foundation of Egypt's (and Africa's) first mosque, theMosque of 'Amr ibn al-'As;though rebuilt many times over the centuries, it still exists today. Its interior consists of a large hypostyle hall with an internal rectangular courtyard.[41]The oldest well-preserved monument of the Islamic period in Egypt is theNilometeron the island ofRawdain Cairo, built in 861.[42]

After reaching its apogee, the Abbasid Caliphate, which ruled most of theMuslim world,became fragmented into regional states in the 9th century which were formally obedient to the caliphs butde factoindependent.[43]In Egypt,Ahmad ibn Tulunestablished a short-lived dynasty, theTulunids,and built himself a new capital,Al-Qata'i,near Fustat. Its principal surviving monument is a largecongregational mosque,known as theIbn Tulun Mosque,which was completed in 879. It was strongly influenced by Abbasid architecture inSamarraand remains one of the most notable and best-preserved examples of 9th-century architecture from the Abbasid Caliphate.[44]The structure consists of a large open courtyard surrounded on four sides by roofed aisles divided by rows of pointed arches supported by large rectangular pillars. The arches and windows are decorated withcarved stuccofeaturinggeometricand Samarran-style vegetal motifs.[45]

Fatimid period[edit]

In the early 10th century, theFatimid Caliphaterose to power inIfriqiya(central North Africa), establishing itself as a rival to Abbasid influence. Afterconquering Egyptin 969, the Fatimids moved their center of power to Egypt in 970 by founding another capital,Cairo,a short distance north of Fustat.[46]Fatimid architecturein Egypt followed Tulunid techniques and used similar materials, but also developed some of its own. Their first congregational mosque in Cairo wasal-Azhar Mosque,founded in the same year as the city itself. This mosque became the spiritual center for theIsmaili Shi'abranch of Islam, which the Fatimids followed. Like other congregational mosques of the era, it consists of an open-air courtyard and a covered hypostyle prayer hall. Other notable Fatimid monuments include the largeMosque of al-Hakim(built 990 to 1013), the smallAqmar Mosque(1125) with its richly-decorated street façade, and the domedMashhad of Sayyida Ruqayya(1133), notable for itsmihrabof elaborately-carvedstucco.Under the powerfulvizierBadr al-Jamali(r. 1073–1094), the city walls were rebuilt in stone along with several monumental gates, three of which have survived to the present-day:Bab al-Futuh,Bab al-Nasr,andBab Zuweila).[46]

The Fatimids made wide usage of the"keel" archand also introducedmuqarnas(stalactite-like niches) in the shapes ofsquinches(a technique for transitioning from a square space below to a circular dome above).[47]Floral,arabesque,and geometric motifs were the main motifs of surface decoration, carved in stucco, wood, and sometimes stone. Keel arch-shaped niches, with a centrally-radiating fluted motif, also appear and became a characteristic of later architectural decoration in Cairo.[48]Figural representations,generally taboo in Islamic religious architecture, were used in the architectural decoration of Fatimid palaces.[49]

Ayyubid period[edit]

Saladin dethroned the Fatimid caliphs in 1171 and inaugurated theAyyubid dynasty,which retained Cairo as its capital.[50]Military architecture was the supreme expression of the Ayyubid period. The most radical change Saladin implemented in Egypt was enclosing Cairo and Fustat within a single city wall.[51]Some fortification techniques were learned from the Crusaders, such as curtain walls following the natural topography. Many were also inherited from the Fatimids, likemachicolationsand round towers; other techniques were developed by the Ayyubids themselves, such as concentric planning.[52]

In 1176, the construction of theCairo Citadelbegan under Saladin's orders.[53]It was to become the center of government in Egypt until the 19th century, with expansions and renovations.[40]The Citadel was completed under sultanAl-Kamil(r. 1218–1238).[54]All of al-Kamil's fortifications can be identified by their embossed, rusticated masonry, whereas Saladin's towers have smooth dressed stones. This heavier rustic style became a common feature in other Ayyubid fortifications.[55]After the domination of the Shi'a Fatimids, the Ayyubid rulers were also eager to promote the restoration ofSunniIslam by building Sunnimadrasas.[51]The first Sunni madrasa in Egypt was commissioned by Saladin near the importantMausoleum of Imam al-Shafi'iin Cairo'sSouthern Cemetery.[56]

The end of the Ayyubid period and the start of theMamluk periodwas marked by the creation of the first multi-purpose funerary complexes in Cairo. The last Ayyubid sultan,al-Salih Ayyub,founded theMadrasa al-Salihiyyain 1242. His wife,Shajar ad-Durr,added his mausoleum to it after his death in 1249, and then builther own mausoleum and madrasa complexin 1250 at another location south of the Citadel.[57]These two complexes were the first in Cairo to combine a founder's mausoleum with a religious and charitable complex, which would come to characterize the nature of most Mamluk royal foundations afterward.[57][58]

Mamluk period[edit]

TheMamluks,a military corps under the Ayyubid dynasty recruited from slaves, took power in 1250, ruling over Egypt and much of the Middle East until theOttoman conquest of 1517.Despite their often violent internal politics, the Mamluk sultans were generous patrons of architecture and are responsible for much of the monumental heritage ofhistoric Cairo.[59][60]Some long-reigning sultans, such asAl-Nasir Muhammad(r. 1293–1341, with interruptions) andQaytbay(r. 1468–1496), were especially prolific.[61]Under Mamluk rule, Cairo reached its apogee of wealth and population in the 14th century (prior to its second rise in the modern period).[62]

Mamluk architectureis distinguished in part by the construction of multi-functional buildings, whose floor plans became increasingly creative and complex due to the city's limited available space and the desire to make monuments visually dominant in their urban surroundings.[63][59][60]Patrons, including sultans and high-ranking emirs, typically set out to build mausoleums for themselves, but attached to them various charitable structures such as madrasas,khanqahs,sabils,or mosques. The revenues and expenses of these charitable complexes were governed by inalienablewaqfagreements that also served the secondary purpose of ensuring some form of income or property for the patrons' descendants.[60][63]

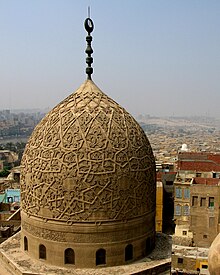

The cruciform or four-iwanfloor plan was adopted for madrasas and became more common for new monumental complexes than the traditional hypostyle mosque, although the vaulted iwans of the early period were replaced with flat-roofed iwans in the later period.[64][65]The decoration of monuments also became more elaborate over time, with stone-carving and polychrome marble mosaic paneling (includingablaqstonework) replacing stucco as the most dominant architectural decoration. Monumental decorated entrance portals became common compared to earlier periods, often sculpted withmuqarnas.Influences fromSyria,Ilkhanid Iran,and possibly evenVenicewere evident in these trends.[66][67]Minarets,which were also elaborate, usually consisted of three tiers separated by balconies, with each tier having a different design than the others. Late Mamluk minarets, for example, most typically had an octagonal shaft for the first tier, a round shaft on the second, and a lantern structure with finial on the third level.[68][69]Domes evolved from wooden or brick structures, sometimes of bulbous shape, to pointed stone domes with complexgeometricorarabesquemotifs carved into their outer surfaces.[70]The peak of this stone dome architecture was achieved under the reign of Qaytbay in the late 15th century.[71]

Ottoman and early modern period[edit]

Ottoman period[edit]

After the Ottoman conquest of 1517, new Ottoman-style buildings were introduced; however, the Mamluk style continued to be repeated or combined withOttoman architecturalelements in new buildings.[72]The new Ottoman features included the "pencil" -style Ottoman minarets, mosques planned around a central dome, and colorfultiledecoration.[73]Compared to earlier periods, however, architectural patronage was smaller, as Egypt was no longer the center of an empire, but merely anOttoman province.[73]Some building types from the late Mamluk period, such as sabil-kuttabs (a combination of sabil andkuttab) and multi-storiedcaravanserais(wikalas orkhans), actually grew in number during the Ottoman period.[72]

In the 19th century, under thede factoindependent rule ofMuhammad Aliand his successors, new buildings, such as theMosque of Muhammad Aliin the Citadel (built 1830–1848), conspicuously employedOttoman Baroqueand contemporary late OttomanWesternizingdecoration. The more strictly Ottoman form of Muhammad Ali's mosque and its European-style decoration was a radical break from the traditional Mamluk-influenced architecture of Cairo and symbolized Muhammad Ali's efforts to bring Egypt into a new era.[74][75][76][77]The new style of this period also appears in multiple sabil-kuttabs built throughout the city, which feature curved street facades carved with new leaf,garland,andsunburstmotifs.[78][79]

Khedivate period and European influence[edit]

One of Muhammad Ali's grandsons,Isma'il,ruling officially asKhedivebetween 1863 and 1879, pushed even further formodernization.He oversaw the construction of the modernSuez Canal,which was inaugurated in 1869.[81]Along with this enterprise, he also undertook the construction of a vast new district in European style to the north and west of the historic center of Cairo. The new city emulatedHaussman's 19th-centuryreforms of Paris,with grand boulevards and squares forming part of the urban plan.[82]Isma'il even employed architects recommended byBaron Haussman.Although never fully completed to the extent of Isma'il's vision, this new expansion composes much of what isdowntown Cairotoday.[82]This left the old historic districts of Cairo, including the walled city, relatively neglected. Even the Citadel lost its status as the royal residence when Isma'il moved to the newAbdin Palacein 1874.[83]The city ofIsmailia,named after Isma'il, was founded in 1863 by French engineerFerdinand de Lessepsas a base for workers on the Suez Canal project. It too was laid out with wide boulevards and squares.[84]

These projects exemplified a trend ofFrancophiliathat was present during this time in both Cairo and Istanbul (the Ottoman capital), as the elites of both places began to value French ideas and Parisian aesthetics.[80]In the design of buildings, not only Paris but alsoViennawere sources of inspiration.Austro-Hungarianinterpretations of French andItalianatestyles served as models for architecture during the reign of Khedive'Abbas Hilmi(r. 1892–1914). TheBeaux-ArtsandSecession(AustrianArt Nouveau) styles of Vienna are widely evident in new buildings around the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.[80]Egypt's firstarchitectural competitionwas held in 1894 for the design of theEgyptian Museum,housing the country's growing collection of antiquities. The winner, French architect Marcel Dourgnon, designed a largeNeoclassicalbuilding completed in 1902.[85]

In the late 19th century and early 20th century a "neo-Mamluk" style appeared, partly as a nationalist response against Ottoman and European styles, in an effort to promote local "Egyptian" styles (though the architects were sometimes Europeans).[75][80]Examples of this style are theMausoleum of Tawfiq Pasha(1894),[80][86]the presentSayyida Nafisa Mosque(1895),[80]theSayyida Aisha Mosque(1894–1896),[80]theMuseum of Islamic Artsbuilding (1903),[87]theAl-Rifa'i Mosque(1869–1911),[75][88]and theAbu al-Abbas al-Mursi Mosquein Alexandria (1929–1945).[88]

New suburbs and towns around Cairo were created in the early 20th century and experimented with different styles.[89]Heliopolis,the first Cairo suburb established on the desert fringes, holds one of the most important concentrations of significant early 20th century architecture outside of downtown Cairo. It was founded in 1906 by a private partnership between the BelgianÉdouard Empainand the EgyptianBoghos Nubar Pashaand it grew over the following decades.[90]Its buildings were designed in a wide range of styles, including Neo-Islamic[90]or Neo-Mamluk,[75][80]Art Deco,oreclecticcombinations of Orientalist andModerniststyles.[90]The Heliopolis Company buildings lining some of its main streets, completed towards 1908, are in a Neo-Islamic/Neo-Mamluk style designed by Ernest Jaspar,[91]whileBaron Empain's own palace,completed in 1911 byAlexandre Marcel,is a flamboyant imitation ofHindu temple architectureadapted to the layout of a Beaux-Arts building.[92]

A "neo-Pharaonic" style also appeared in the early 20th century and was used by some architects. TheMausoleum of Saad Zaghloul(1928–1931), designed by Mustafa Fahmi (d. 1972), is one example.[84]ThoughEgyptian Revival architecturewas popular in Europe and North America during the 19th century, its popularity as a national style in Egypt itself was ultimately limited.[93]

Modernism and present day[edit]

20th century modernism[edit]

From the 1930s, Modernism began to dominate Cairo's architecture, replacing the earlier revivalist styles.[94]Among the prominent architects wasSayed Karim,who championed theInternational StyleandBrutalism.[95]He also founded the first Arabic-language magazine on architecture,al-'Imarah(Arabic:مجلة العِمارة), which promoted contemporary designs and was an important step in the development of modern Egypt's architectural culture.[95]

Towards the mid-20th century, some Egyptian architects began challenging the dominance of Western styles and ideas.[84]The most influential wasHassan Fathy(living 1900–1989), who began his career in the 1930s. He aimed to use traditional vernacular mud-brick construction, adapted to modern context.[84][96]His architecture was "aimed at comforting its subjects toward... modernity"[vague].[97]: ii The village ofNew Gourna(built 1945–1948), nearLuxor,is an example of his works.[96]Ramses Wissa Wassef,one of Fathy's students, is another example of this trend. He adapted features fromNubianand mudbrick architecture in Upper Egypt into his buildings.[84]

There were repeated efforts in the 20th century to address the booming population through large-scale urban developments and housing projects in various locations. A number of new satellite cities were founded around Cairo with this intention.[84]Newer public buildings and monuments also date from the second half of the 20th century after the1952 revolution.In the 1950s PresidentGamal Abdel NasserremodeledTahrir Square,the symbolic heart of the capital. Next to the square, the newArab League Headquarterswas erected on the site of a demolished British army barracks.[98]TheCairo Tower,a 187-meter tall observation tower with a lotus-motif design, was built between 1955 and 1961[99]and designed by Egyptian architectNaoum Shebib.[100]It was the tallest all-concrete structure in the world upon completion[99]and it is the most recognizable symbol of post-1952 Egyptian architecture.[100]TheCairo Opera House,originally opened in 1869 under Khedive Isma'il and designed as an imitation ofLa ScalainMilan,[101]burned down in 1971. It was replaced by a new opera house and cultural complex begun in 1985 and opened in 1988, designed by a Japanese architectural firm.[84]In 1975, PresidentAnwar Sadatopened theUnknown Soldier Memorial,designed in the shape of a hollow pyramid, in Cairo.[102](Sadat was later buried here afterhis assassination.[103])

21st century[edit]

Postmodernismdid not take hold in Cairo in the last decade of the 20th century as it did elsewhere; at least not consciously.[104]At the turn of the millennium, historicist or pseudo-historicist trends began to reappear, as seen in theSupreme Courtbuilding (1999), which references ancient Egyptian architecture, and theFaisal Islamic BankTower (2000), which references historic Islamic architecture.[104]

In Alexandria, the idea of paying homage to its famousancient librarywith a new building was floated as early as 1972. This was eventually realized as a massive new library, theBibliotheca Alexandrina,which opened in 2002. It is shaped like an inclined cylinder or disk, with the outer walls made of granite carved with characters from all the world'salphabets.[105]

In the tourist center ofSharm El Sheikh,theAl Sahaba Mosque,completed in 2017, is a fusion of Ottoman, Mamluk, and Fatimid styles. It was designed pro bono by Egyptian architect Fouad Tawfik Hafez.[106][107][108]

Conservation challenges[edit]

Much of Egypt's 19th-century and 20th-century architecture has been vulnerable to demolition and redevelopment. Modernist architecture is often seen as having little cultural value and receives relatively little attention or documentation, despite the large volume of construction activity in cities like Cairo during the modern period.[109]Egyptian law also requires buildings to be at least a hundred years old before being eligible for heritage status, leaving much of the country's more recent heritage unprotected.[110]

In recent years, Alexandria's older urban heritage, much of it dating from the colonial period, has come under threat from poorly-regulated demolitions and development.[111][112][113]In Cairo, a large number of modern heritage buildings have disappeared, ranging from former villas to large-scale buildings and city blocs.[114]Parts of Cairo's historicNorthern Cemetery(also known as the City of the Dead), which contains funerary architecture built across many centuries, are also under threat from government infrastructure projects. Parts of the necropolis, mainly dating from the early 20th century, were demolished in 2020. The plans have been criticized by some scholars, architects, and archeologists.[115][116]In Luxor, the historic Tawfiq Pasha Andraos Palace, built in 1897 near the ancientLuxor Temple,was demolished in 2021, sparking criticism and debate.[117][118][119]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^Behrens-Abouseif 1989,pp. 58–62.

- ^Wildung 2009,p. 26.

- ^ab"Pyramids of Giza | National Geographic".History.2017-01-21. Archived fromthe originalon February 19, 2021.Retrieved2023-02-02.

- ^Associated Press in Cairo (2010-01-11)."Great Pyramid tombs unearth 'proof' workers were not slaves".the Guardian.Retrieved2023-02-02.

- ^Lesko, Leonard H. (2018).Pharaoh's Workers: The Villagers of Deir el Medina.Cornell University Press.ISBN978-1-5017-2761-0.

- ^Baker, Rosalie F.; Baker III, Charles F. (2001).Ancient Egyptians: People of the Pyramids.Oxford University Press. p. 168.ISBN978-0-19-802851-2.

- ^abcdefgh"Ancient Egyptian architecture | Types, History, & Facts | Britannica".Encyclopedia Britannica.21 October 2022.Retrieved2023-01-10.

- ^abWildung 2009,pp. 7–9.

- ^abNicholson, Paul T.; Shaw, Ian; Press, Cambridge University (2000).Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology.Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–6.ISBN978-0-521-45257-1.

- ^Malek, Jaromir (2003).Egypt: 4000 Years of Art.Phaidon Press. p. 5.ISBN978-0-7148-4200-4.

- ^abLucas, A.; Harris, J. (2012).Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries.Dover Publications. pp. 52–61.ISBN978-0-486-14494-8.

- ^abcdCurl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan (2015). "Egyptian architecture".The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture.Oxford University Press. p. 256.ISBN978-0-19-105385-6.

- ^abcdFleming, John; Honour, Hugh; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1998). "Egyptian architecture".The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture(5th ed.). Penguin Books. pp. 168–171.ISBN978-0-14-051323-3.

- ^Wildung 2009,p. 149.

- ^Magli, Giulio (2013).Architecture, Astronomy and Sacred Landscape in Ancient Egypt.Cambridge University Press. p. 184.ISBN978-1-107-24502-0.

- ^Wildung 2009,pp. 8–9.

- ^Wildung 2009,p. 198.

- ^abcdeMcKenzie 2007,pp. 1–5.

- ^Miles, Margaret M. (2010-06-01)."Review: The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, c. 300 BC to AD 700, by Judith McKenzie".Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians.69(2): 279–280.doi:10.1525/jsah.2010.69.2.279.ISSN0037-9808.

- ^McKenzie 2007,pp. 192–194.

- ^abcBolman, Elizabeth S., ed. (2016).The Red Monastery Church: Beauty and Asceticism in Upper Egypt.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-21230-3.

- ^abcdeFleming, John; Honour, Hugh; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1998). "Coptic architecture".The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture(5th ed.). Penguin Books. p. 128.ISBN978-0-14-051323-3.

- ^Meinardus 2002,p. xx.

- ^abMcKenzie 2007,p. 232.

- ^abMartin, Matthew (2006)."Observations on the Paintings of the Exodus Chapel, Bagawat Necropolis, Kharga Oasis, Egypt".In Burke, John; Betka, Ursula; Buckley, Penelope; Hay, Kathleen; Scott, Roger; Stephenson, Andrew (eds.).Byzantine Narrative: Papers in honour of Roger Scot.Brill. pp. 233–236.ISBN978-90-04-34487-7.

- ^abcMeinardus 2002,p. 256.

- ^McKenzie 2007,pp. 232–233.

- ^Gawdat, Gabra; Vivian, Tim (2002).Coptic Monasteries: Egypt's Monastic Art And Architecture.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-977-424-691-3.

- ^Meinardus 2002.

- ^Gabra, Gawdat; Eaton-Krauss, Marianne (2007).The Illustrated Guide to the Coptic Meuseum and Churches of Old Cairo.American University in Cairo Press.ISBN978-977-416-007-3.

- ^abSpeake, Graham, ed. (2000)."Saint Catherine's Monastery, Sinai".Encyclopedia of Greece and the Hellenic Tradition.Routledge. pp. 1480–1482.ISBN978-1-135-94206-9.

- ^abHatlie, Peter (2013). "Sinai, Monastery of St. Catherine". In Erskine, Andrew; Hollander, David B.; Papaconstantinou, Arietta; Bagnall, Roger S.; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B.; Huebner, Sabine R. (eds.).The Encyclopedia of Ancient History(1 ed.). Wiley.doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah03219.ISBN978-1-4051-7935-5.

- ^Evans, Helen C. (2004).Saint Catherine's Monastery, Sinai, Egypt: A Photographic Essay.Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 15.ISBN978-1-58839-109-4.

- ^Berger, Sidney E. (2016).The Dictionary of the Book: A Glossary for Book Collectors, Booksellers, Librarians, and Others.Rowman & Littlefield. p. 229.ISBN978-1-4422-6340-6.

- ^abHamilton, Bernard; Jotischky, Andrew (2022). "The Mount Sinai Monastery: A Successful Example of Shared Holy Space".Al-Masāq.34(2): 127–139.doi:10.1080/09503110.2021.2007715.ISSN0950-3110.S2CID247508246.

- ^Bloom & Blair 2009,pp. 84–85.

- ^Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (2014)."Between Quarry and Magic: The Selective Approach to Spolia in the Islamic Monuments of Egypt".In Payne, Alina (ed.).Dalmatia and the Mediterranean: Portable Archaeology and the Poetics of Influence.p. 402.

- ^Bloom & Blair 2009,pp. 105, 147.

- ^Williams 2018,p. 7.

- ^abRaymond 2000.

- ^O'Kane 2016,p. 2.

- ^Behrens-Abouseif 1989,p. 50.

- ^Kennedy, Hugh (2004).The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth to the Eleventh Century(2nd ed.). Routledge.ISBN978-0-582-40525-7.

- ^Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001,pp. 31–32.

- ^Petersen 1996,p. 44.

- ^abBehrens-Abouseif 1989,p. 58–75.

- ^Bloom & Blair 2009,pp. 105–109.

- ^Behrens-Abouseif 1989,p. 10.

- ^Bloom, Jonathan M. (2012). "Fāṭimid art and architecture". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.).Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three.Brill.ISBN978-90-04-16165-8.

- ^Raymond 2000,p. 80.

- ^abYeomans 2006,pp. 104–105

- ^Petersen 1996,p. 26

- ^Yeomans 2006,p. 107

- ^Yeomans 2006,pp. 109–110

- ^Yeomans 2006,p. 111

- ^Williams 2018,p. 153.

- ^abRuggles, D.F. (2020).Tree of pearls: The extraordinary architectural patronage of the 13th-century Egyptian slave-queen Shajar al-Durr.Oxford University Press.

- ^Behrens-Abouseif 2007,p. 114.

- ^abWilliams 2018.

- ^abcBlair & Bloom 1995,p. 70.

- ^Blair & Bloom 1995,pp. 70, 85–87, 92–93.

- ^Raymond 2000,pp. 118–121, 135–137.

- ^abBehrens-Abouseif 2007.

- ^Behrens-Abouseif 2007,pp. 73–77.

- ^Williams 2018,p. 30.

- ^Williams 2018,pp. 30–31.

- ^Blair & Bloom 1995,pp. 83–84.

- ^Williams 2018,p. 31.

- ^Behrens-Abouseif 2007,p. 79.

- ^Behrens-Abouseif 2007,pp. 80–84.

- ^Williams 2018,p. 34.

- ^abWilliams 2018,p. 17.

- ^abBlair & Bloom 1995,p. 251.

- ^abAl-Asad, Mohammad (1992). "The Mosque of Muhammad ʿAli in Cairo".Muqarnas.9:39–55.doi:10.2307/1523134.JSTOR1523134.

- ^abcdSanders, Paula (2008).Creating Medieval Cairo: Empire, Religion, and Architectural Preservation in Nineteenth-century Egypt.American University in Cairo Press. pp. 39–41.ISBN978-977-416-095-0.

- ^Behrens-Abouseif 1989,p. 168–170.

- ^Williams 2018,p. 264.

- ^Williams 2018,pp. 137, 194, 226, 240, 264–265.

- ^Behrens-Abouseif 1989,p. 167–170.

- ^abcdefghAvcıoğlu, Nebahat; Volait, Mercedes (2017).""Jeux de miroir": Architecture of Istanbul and Cairo from Empire to Modernism ".In Necipoğlu, Gülru; Barry Flood, Finbarr (eds.).A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture.Wiley Blackwell. pp. 1138–1142.ISBN978-1-119-06857-0.

- ^Raymond 2000,p. 309–311.

- ^abRaymond 2000,p. 309–318.

- ^Williams 2018,p. 8-9, 18-19, 260.

- ^abcdefgM. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Egypt".The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture.Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 44–45.ISBN978-0-19-530991-1.

- ^Elshahed 2020,p. 86.

- ^Williams 2018,p. 289.

- ^Williams 2018,pp. 172–173.

- ^abO'Kane 2016,pp. 311–319.

- ^Elshahed 2020,p. 34.

- ^abcElshahed 2020,pp. 34, 310–311.

- ^Elshahed 2020,p. 178.

- ^Elshahed 2020,p. 319.

- ^Elshahed 2020,p. 46.

- ^Elshahed 2020,p. 35.

- ^abElshahed 2020,pp. 36–38, 43.

- ^abFleming, John; Honour, Hugh; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1998). "Fathy".The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture(5th ed.). Penguin Books. p. 189.ISBN978-0-14-051323-3.

- ^Shaker, Mohamed Monkez (2019).Comfortable Modernization: Hassan Fathy's Architecture and the Decolonization of Egypt(Thesis). University of California Los Angeles.ProQuest2328013156.

- ^AlSayyad, Nezar (2022).Routledge Handbook on Cairo: Histories, Representations and Discourses.Taylor & Francis.ISBN978-1-000-78789-4.

- ^abGoldschmidt, Arthur Jr. (2013)."Cairo Tower".Historical Dictionary of Egypt.Scarecrow Press. p. 89.ISBN978-0-8108-8025-2.

- ^abElshahed 2020,p. 135.

- ^Raymond 2000,p. 315.

- ^Podeh, Elie (2011).The Politics of National Celebrations in the Arab Middle East.Cambridge University Press. p. 88.ISBN978-1-107-00108-4.

- ^AlSayyad, Nezar (2013).Cairo: Histories of a City.Harvard University Press. p. 255.ISBN978-0-674-07245-9.

- ^abElshahed 2020,pp. 41–42.

- ^"Bibliotheca Alexandrina | History & Facts | Britannica".Encyclopedia Britannica.19 September 2019.Retrieved2023-01-11.

- ^Rafik, Farah (2022-05-14)."Sharm El Sheikh's 'Al Sahaba Mosque' Blends Spirituality and Tourism".Egyptian Streets.Retrieved2023-01-27.

- ^"In photos:10 facts you may not know about the newly inaugurated 'Sahaba Mosque' in Sharm El-Sheikh".Egypt Independent.2017-03-28.Retrieved2023-01-27.

- ^"Al Sahaba Mosque | Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt | Attractions".Lonely Planet.Retrieved2023-01-27.

- ^Elshahed 2020,pp. 24–31.

- ^Elshahed 2020,pp. 24–25.

- ^Rollins, Tom (19 February 2015)."Understanding Alexandria's embattled urban heritage".Middle East Eye.Retrieved2023-01-11.

- ^Sherief, Abdel-Rahman (2013-04-23)."Architectural heritage under threat in Alexandria - Daily News Egypt".Daily News Egypt.Retrieved2023-01-11.

- ^Kingsley, Patrick (6 February 2014)."Demolition of Alexandria architectural gem begins".The Guardian.Retrieved2023-01-26.

- ^Elshahed 2020,p. 25.

- ^Español, Marc (7 April 2022)."Threat of demolition looms over Cairo's historic necropolis".Al-Monitor.Retrieved2023-01-26.

- ^"Egypt denies destroying ancient Islamic cemeteries to build bridge".Arab News.2020-07-21.Retrieved2023-01-26.

- ^Ayyad, Ibrahim (6 September 2021)."Destruction of 120-year-old palace sparks anger in Egypt - Al-Monitor: Independent, trusted coverage of the Middle East".Al-Monitor.Retrieved2023-01-26.

- ^Abu Zaid, Mohammed (2021-08-26)."Historic Egyptian palace being razed as it is on verge of collapse: Official".Arab News.Retrieved2023-01-27.

- ^"Demolition of Tawfiq Andraos Palace - Egypt - Al-Ahram Weekly".Ahram Online.24 August 2021.Retrieved2023-01-27.

Sources[edit]

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1989).Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction(PDF).Leiden, the Netherlands: E.J. Brill.ISBN978-90-04-09626-4.

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (2007).Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of Architecture and its Culture.Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.ISBN978-977-416-077-6.

- Blair, Sheila; Bloom, Jonathan M. (1995).The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250–1800.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-06465-0.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Architecture".The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture.Vol. 1. Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-530991-1.

- Elshahed, Mohamed (2020).Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide.American University in Cairo Press.ISBN978-977-416-869-7.

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2001).Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-08869-4.Retrieved2013-03-17.

- McKenzie, Judith (2007).The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, c. 300 BC to AD 700.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-11555-0.

- Meinardus, Otto F. A. (2002).Two Thousand Years of Coptic Christianity.American University in Cairo Press.ISBN978-977-424-757-6.

- O'Kane, Bernard (2016).The Mosques of Egypt.American University of Cairo Press.ISBN978-977-416-732-4.

- Petersen, Andrew (1996),Dictionary of Islamic Architecture,Routledge,ISBN978-0-415-06084-4

- Raymond, André (2000) [1993].Cairo.Translated by Wood, Willard. Harvard University Press.ISBN978-0-674-00316-3.

- Wildung, Dietrich (2009).Egypt: From Prehistory to the Romans.Taschen.ISBN978-3-8365-1030-1.

- Williams, Caroline (2018).Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide(7th ed.). The American University in Cairo Press.ISBN978-977-416-855-0.

- Yeomans, Richard (2006),The Art and Architecture of Islamic Cairo,Garnet & Ithaca Press,ISBN978-1-85964-154-5

Further reading[edit]

- Briggs, Martin S. (1921). "The Architecture of Saladin and the Influence of the Crusades (A. D. 1171-1250)".The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs.38(214): 10–20.ISSN0951-0788.JSTOR861268.

- Grabar, Oleg (1961). "Review of The Muslim Architecture of Egypt".Ars Orientalis.4:422–428.ISSN0571-1371.JSTOR4629167.

- El-Ashmouni, Marwa M.; Salama, Ashraf M. (2022).Influence and Resistance in Post-Independence Egyptian Architecture.Taylor & Francis.ISBN978-1-000-61764-1.

External links[edit]

- Digital copies ofMajallat al-Imarah(1939 to 1949), the modern architecture magazine founded by Sayyed Karim, hosted atArchNet