Arcturus

| Observation data EpochJ2000EquinoxJ2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Boötes |

| Pronunciation | /ɑːrkˈtjʊərəs/ |

| Right ascension | 14h15m39.7s[1] |

| Declination | +19° 10′ 56″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude(V) | −0.05[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | K1.5 III Fe−0.5[3] |

| Apparent magnitude(J) | −2.25[2] |

| U−Bcolor index | +1.28[2] |

| B−Vcolor index | +1.23[2] |

| R−Icolor index | +0.65[2] |

| Note (category: variability): | H and K emission vary. |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity(Rv) | −5.19[4]km/s |

| Proper motion(μ) | RA:−1093.45[5]mas/yr Dec.:−1999.40[5]mas/yr |

| Parallax(π) | 88.83 ± 0.54mas[1] |

| Distance | 36.7 ± 0.2ly (11.26 ± 0.07pc) |

| Absolute magnitude(MV) | −0.30±0.02[6] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 1.08±0.06[7]M☉ |

| Radius | 25.4±0.2[7]R☉ |

| Luminosity | 170[8]L☉ |

| Surface gravity(logg) | 1.66±0.05[7]cgs |

| Temperature | 4,286±30[7]K |

| Metallicity[Fe/H] | −0.52±0.04[7]dex |

| Rotational velocity(vsini) | 2.4±1.0[6]km/s |

| Age | 7.1+1.5 −1.2[7]Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| Data sources: | |

| Hipparcos Catalogue, CCDM(2002), Bright Star Catalogue (5th rev. ed.), VizieR catalog entry | |

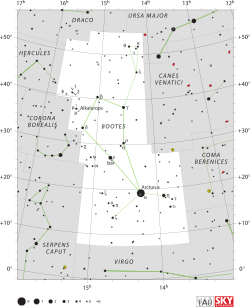

Arcturusis the brighteststarin thenorthernconstellationofBoötes.With anapparent visual magnitudeof −0.05,[2]it is thefourth-brighteststar in thenight sky,and the brightest in thenorthern celestial hemisphere.The name Arcturus originated fromancient Greece;it was then cataloged asα BoötisbyJohann Bayerin 1603, which isLatinizedtoAlpha Boötis.Arcturus forms one corner of theSpring Triangleasterism.

Located relatively close at 36.7light-yearsfrom theSun,Arcturus is ared giantofspectral typeK1.5III—an aging star around 7.1 billion years old that has used up itscorehydrogenandevolvedoff themain sequence.It is about the same massas the Sun,but has expanded to 25 timesits sizeand is around 170 times as luminous. Its diameter is 35 million kilometres.

Nomenclature[edit]

The traditional nameArcturusis Latinised from theancient GreekἈρκτοῦρος (Arktouros) and means "Guardian of the Bear",[9]ultimately from ἄρκτος (arktos), "bear"[10]and οὖρος (ouros), "watcher, guardian".[11]

Thedesignationof Arcturus asα Boötis(LatinisedtoAlpha Boötis) was made byJohann Bayerin 1603. In 2016, theInternational Astronomical Unionorganized aWorking Group on Star Names(WGSN) to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016 included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN, which includedArcturusfor α Boötis.[12][13]

Observation[edit]

With anapparent visual magnitudeof −0.05, Arcturus is the brightest star in thenorthern celestial hemisphereand thefourth-brightest starin the night sky,[14]afterSirius(−1.46 apparent magnitude),Canopus(−0.72) andα Centauri(combined magnitude of −0.27). However, α Centauri AB is abinary star,whose components are each fainter than Arcturus. This makes Arcturus the third-brightest individual star, just ahead of α Centauri A (officially namedRigil Kentaurus), whose apparent magnitudeis −0.01.[15]The French mathematician and astronomerJean-Baptiste Morinobserved Arcturus in the daytime with a telescope in 1635. This was the first recorded full daylight viewing for any star other than theSunandsupernovae.Arcturus has been seen at or just before sunset with the naked eye.[15]

Arcturus is visible from both ofEarth's hemispheres as it is located 19° north of thecelestial equator.The starculminatesat midnight on 27 April, and at 9 p.m. on June 10 being visible during the late northern spring or the southern autumn.[16]From thenorthern hemisphere,an easy way to find Arcturus is to follow the arc of the handle of theBig Dipper(or Plough in theUK). By continuing in this path, one can findSpica,"Arc to Arcturus, then spike (or speed on) to Spica".[17][18]Together with the bright starsSpicaandRegulus(orDenebola,depending on the source), Arcturus is part of theSpring Triangleasterism.WithCor Caroli,these four stars form theGreat Diamondasterism.

Ptolemy described Arcturus assubrufa( "slightly red" ): it has a B-V color index of +1.23, roughly midway betweenPollux(B-V +1.00) andAldebaran(B-V +1.54).[15]

η Boötis,or Muphrid, is only 3.3light-yearsdistant from Arcturus, and would have a visual magnitude −2.5, about as bright asJupiterat its brightest from Earth, whereas an observer on the former system would find Arcturus with a magnitude -5.0, slightly brighter thanVenusas seen from Earth, but with an orangish color.[15]

Physical characteristics[edit]

Based upon an annualparallaxshift of 88.83milliarcseconds,as measured by theHipparcossatellite, Arcturus is 36.7light-years(11.26parsecs) from the Sun. The parallaxmargin of erroris 0.54 milliarcseconds, translating to a distance margin of error of ±0.23 light-years (0.069 parsecs).[1]Because of its proximity, Arcturus has a highproper motion,twoarcsecondsa year, greater than anyfirst magnitude starother than α Centauri.

Arcturus is moving rapidly (122 km/s or 270,000 mph) relative to the Sun, and is now almost at its closest point to the Sun. Closest approach will happen in about 4,000 years, when the star will be a few hundredths of a light-year closer to Earth than it is today. (In antiquity, Arcturus was closer to the centre of the constellation.[19]) Arcturus is thought to be anold-disk star,[7]and appears to be moving with a group of 52 other such stars, known as theArcturus stream.[20]

With anabsolute magnitudeof −0.30, Arcturus is, together withVegaand Sirius, one of the most luminous stars in the Sun's neighborhood. It is about 110 times brighter than the Sun in visible light wavelengths, but this underestimates its strength as much of the light it gives off is in theinfrared;total (bolometric) power output is about 180 times that of the Sun. With a near-infraredJ bandmagnitudeof −2.2, onlyBetelgeuse(−2.9) andR Doradus(−2.6) are brighter. The lower output in visible light is due to a lowerefficacyas the star has a lowersurface temperaturethan the Sun.

There have been suggestions that Arcturus might be a member of a binary system with a faint, cool companion, but no companion has been directly detected.[7] In the absence of a binary companion, the mass of Arcturus cannot be measured directly, but models suggest it is slightly greater than that of the Sun. Evolutionary matching to the observed physical parameters gives a mass of1.08±0.06M☉,[7]while the oxygen isotope ratio for a firstdredge-upstar gives a mass of 1.2M☉.[21]The star, given its evolutionary state, is expected to have undergone significant mass loss in the past.[22]The star displaysmagnetic activitythat is heating thecoronalstructures, and it undergoes asolar-type magnetic cyclewith a duration that is probably less than 14 years. A weak magnetic field has been detected in thephotospherewith a strength of around half agauss.The magnetic activity appears to lie along four latitudes and is rotationally modulated.[23]

Arcturus is estimated to be around 6 to 8.5 billion years old,[7]but there is some uncertainty about its evolutionary status.[24]Based upon thecolor characteristicsof Arcturus, it is currently ascending thered-giant branchand will continue to do so until it accumulates a large enough degenerate heliumcoreto ignite thehelium flash.[7]It has likely exhausted thehydrogenfrom its core and is now in its activehydrogen shell burningphase. However, Charbonnel et al. (1998) placed it slightly above thehorizontal branch,and suggested it has already completed the helium flash stage.[24]

Spectrum[edit]

Arcturus hasevolvedoff the main sequence to thered giant branch,reaching anearlyK-typestellar classification.It is frequently assigned the spectral type of K0III,[25]but in 1989 was used as the spectral standard for type K1.5III Fe−0.5,[3]with the suffix notation indicating a mild underabundance of iron compared to typical stars of its type. As the brightest K-typegiantin the sky, it has been the subject of multipleatlaseswith coverage from theultraviolettoinfrared.[26][27]

The spectrum shows a dramatic transition fromemission linesin the ultraviolet to atomicabsorption linesin the visible range and molecular absorption lines in the infrared. This is due to the optical depth of the atmosphere varying with wavelength.[27]The spectrum shows very strong absorption in some molecular lines that are not produced in thephotospherebut in a surrounding shell.[28]Examination ofcarbon monoxidelines show the molecular component of the atmosphere extending outward to 2–3 times the radius of the star, with thechromospheric windsteeply accelerating to 35–40 km/s in this region.[29]

Astronomers term "metals" those elements with higheratomic numbersthanhelium.The atmosphere of Arcturus has an enrichment ofalpha elementsrelative toironbut only about a third of solarmetallicity.Arcturus is possibly aPopulation II star.[15]

Oscillations[edit]

As one of the brightest stars in the sky, Arcturus has been the subject of a number of studies in the emerging field ofasteroseismology.Belmonte and colleagues carried out a radial velocity (Doppler shift of spectral lines) study of the star in April and May 1988, which showed variability with a frequency of the order of a fewmicrohertz(μHz), the highest peak corresponding to 4.3 μHz (2.7 days) with an amplitude of 60 ms−1,with afrequency separationof c. 5 μHz. They suggested that the most plausible explanation for the variability of Arcturus is stellar oscillations.[30]

Asteroseismological measurements allow direct calculation of the mass and radius, giving values of0.8±0.2M☉and27.9±3.4R☉.This form of modelling is still relatively inaccurate, but a useful check on other models.[31]

Possible planetary system[edit]

Hipparcossatelliteastrometrysuggested that Arcturus is abinary star,with the companion about twenty times dimmer than the primary and orbiting close enough to be at the very limits of humans' current ability to make it out. Recent results remain inconclusive, but do support the marginalHipparcosdetection of a binary companion.[32]

In 1993, radial velocity measurements of Aldebaran, Arcturus and Pollux showed that Arcturus exhibited a long-period radial velocity oscillation, which could be interpreted as asubstellar companion.Thissubstellar objectwould be nearly 12 times themass of Jupiterand be located roughly at the same orbital distance from Arcturus as the Earth is from the Sun, at 1.1astronomical units.However, all three stars surveyed showed similar oscillations yielding similar companion masses, and the authors concluded that the variation was likely to be intrinsic to the star rather than due to the gravitational effect of a companion. So far no substellar companion has been confirmed.[33]

Mythology[edit]

One astronomical tradition associates Arcturus with the mythology aroundArcas,who was about to shoot and kill his own motherCallistowho had been transformed into a bear. Zeus averted their imminent tragic fate by transforming the boy into the constellation Boötes, called Arctophylax "bear guardian" by the Greeks, and his mother into Ursa Major (Greek: Arctos "the bear" ). The account is given inHyginus'sAstronomy.[34]

Aratusin hisPhaenomenasaid that the star Arcturus lay below the belt of Arctophylax, and according toPtolemyin theAlmagestit lay between his thighs.[35]

An alternative lore associates the name with the legend aroundIcarius,who gave the gift of wine to other men, but was murdered by them, because they had had no experience with intoxication and mistook the wine for poison. It is stated that Icarius became Arcturus while his dog,Maira,became Canicula (Procyon), although "Arcturus" here may be used in the sense of the constellation rather than the star.[36]

Cultural significance[edit]

As one of thebrightest starsin the sky, Arcturus has been significant to observers since antiquity.

In ancientMesopotamia,it was linked to the godEnlil,and also known as Shudun, "yoke",[19]or SHU-PA of unknown derivation in theThree Stars EachBabylonian star cataloguesand laterMUL.APINaround 1100 BC.[37]

In ancient Greek, the star is found in ancient astronomical literature, e.g. Hesiod'sWork and Days,circa 700 BC,[19]as well as Hipparchus's and Ptolemy's star catalogs. The folk-etymology connecting the star name with the bears (Greek: ἄρκτος, arktos) was probably invented much later.[citation needed]It fell out of use in favour of Arabic names until it was revived in theRenaissance.[38]

InArabic,Arcturus is one of two stars calledal-simāk"the uplifted ones" (the other isSpica). Arcturus is specified as السماك الرامحas-simāk ar-rāmiħ"the uplifted one of the lancer". The termAl Simak Al Ramihhas appeared in Al Achsasi Al Mouakket catalogue (translated intoLatinasAl Simak Lanceator).[39]This has been variouslyromanizedin the past, leading to obsolete variants such asAramecandAzimech.For example, the nameAlramihis used inGeoffrey Chaucer'sA Treatise on the Astrolabe(1391). Another Arabic name isHaris-el-sema,fromحارس السماءħāris al-samā’"the keeper of heaven".[40][41][42]orحارس الشمالħāris al-shamāl’"the keeper of north".[43]

InIndian astronomy,Arcturus is called Swati orSvati(Devanagari स्वाति, Transliteration IAST svāti, svātī́), possibly 'su' + 'ati' ( "great goer", in reference to its remoteness) meaning very beneficent. It has been referred to as "the real pearl" inBhartṛhari's kāvyas.[44]

InChinese astronomy,Arcturus is calledDa Jiao(Chinese:Đại giác;pinyin:Dàjiǎo;lit.'great horn'), because it is the brightest star in theChinese constellationcalledJiao Xiu(Chinese:Giác túc;pinyin:Jiǎo Xiǔ;lit.'horn star'). Later it became a part of another constellationKang Xiu(Chinese:Kháng túc;pinyin:Kàng Xiǔ).

TheWotjobalukKooripeople of southeastern Australia knew Arcturus asMarpean-kurrk,mother ofDjuit(Antares) and another star in Boötes,Weet-kurrk[45](Muphrid).[46]Its appearance in the north signified the arrival of the larvae of thewood ant(a food item) in spring. The beginning of summer was marked by the star's setting with the Sun in the west and the disappearance of the larvae.[45]The people ofMilingimbi IslandinArnhem Landsaw Arcturus and Muphrid as man and woman, and took the appearance of Arcturus at sunrise as a sign to go and harvestrakiaorspikerush.[47]TheWeilwanof northern New South Wales knew Arcturus asGuembila"red".[47]: 84

PrehistoricPolynesian navigatorsknew Arcturus asHōkūleʻa,the "Star of Joy". Arcturus is thezenithstar of theHawaiian Islands.Using Hōkūleʻa and other stars, the Polynesians launched their double-hulled canoes fromTahitiand theMarquesas Islands.Traveling east and north they eventually crossed theequatorand reached thelatitudeat which Arcturus would appear directly overhead in the summer night sky. Knowing they had arrived at the exact latitude of the island chain, they sailed due west on thetrade windsto landfall. If Hōkūleʻa could be kept directly overhead, they landed on the southeastern shores of theBig Islandof Hawaii. For a return trip to Tahiti the navigators could use Sirius, the zenith star of that island. Since 1976, thePolynesian Voyaging Society'sHōkūleʻahas crossed the Pacific Ocean many times under navigators who have incorporated thiswayfindingtechnique in their non-instrument navigation.

Arcturus had several other names that described its significance to indigenousPolynesians.In theSociety Islands,Arcturus, calledAna-tahua-taata-metua-te-tupu-mavae( "a pillar to stand by" ), was one of the ten "pillars of the sky", bright stars that represented the ten heavens of theTahitianafterlife.[48]InHawaii,the pattern of Boötes was calledHoku-iwa,meaning "stars of the frigatebird". This constellation marked the path forHawaiʻiloaon his return to Hawaii from the South Pacific Ocean.[49]The Hawaiians called ArcturusHoku-leʻa.[50]It was equated to theTuamotuanconstellationTe Kiva,meaning "frigatebird",which could either represent the figure of Boötes or just Arcturus.[51]However, Arcturus may instead be the Tuamotuan star calledTuru.[52]The Hawaiian name for Arcturus as a single star was likelyHoku-leʻa,which means "star of gladness", or "clear star".[53]In theMarquesas Islands,Arcturus was probably calledTau-touand was the star that ruled the month approximating January. TheMāoriandMorioricalled itTautoru,a variant of the Marquesan name and a name shared withOrion's Belt.[54]

InInuit astronomy,Arcturus is called the Old Man (UttuqalualukinInuit languages) and The First Ones (Sivulliikin Inuit languages).[55]

TheMiꞌkmaqof eastern Canada saw Arcturus asKookoogwéss,the owl.[56]

Early-20th-century Armenian scientistNazaret Daghavariantheorized that the star commonly referred to inArmenian folkloreasGutani astgh(Armenian:Գութանի աստղ; lit. star of the plow) was in fact Arcturus, as theconstellationofBoöteswas called "Ezogh" (Armenian:Եզող; lit. the person who is plowing) by Armenians.[57]

In popular culture[edit]

InAncient Rome,the star's celestial activity was supposed to portend tempestuous weather, and a personification of the star acts as narrator of the prologue toPlautus' comedyRudens(circa 211 BC).[58][59]

TheKāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra,compiled at the end of the 4th century or beginning of the 5th century, names one ofAvalokiteśvara'smeditative absorptionsas "The face of Arcturus".[60]

One of the possible etymologies offered for the name "Arthur"assumes that it is derived from" Arcturus "and that the late 5th to early 6th-century figure on whom the myth ofKing Arthuris based was originally named for the star.[59][61][62][63][64][65]

In theMiddle Ages,Arcturus was considered aBehenian fixed starand attributed to the stoneJasperand theplantainherb.Cornelius Agrippalisted itskabbalisticsign![]() under the alternate nameAlchameth.[66]

under the alternate nameAlchameth.[66]

Arcturus's light was employed in the mechanism used to open the1933 Chicago World's Fair.The star was chosen as it was thought that light from Arcturus had started its journey at about the time of theprevious Chicago World's Fairin 1893 (at 36.7 light-years away, the light actually started in 1896).[67]

At the height of the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln observed Arcturus through a 9.6-inch refractor telescope when he visited the Naval Observatory in Washington, DC, in August, 1863.[68]

References[edit]

- ^abcdvan Leeuwen, Florian (November 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction".Astronomy and Astrophysics.474(2). Paris, France: 653–64.arXiv:0708.1752.Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V.doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357.S2CID18759600.

- ^abcdefDucati, J. R. (2002). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system".CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues.2237:0.Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D.

- ^abKeenan, Philip C.; McNeil, Raymond C. (1989). "The Perkins catalog of revised MK types for the cooler stars".The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.71:245.Bibcode:1989ApJS...71..245K.doi:10.1086/191373.

- ^Massarotti, Alessandro; Latham, David W.; Stefanik, Robert P.; Fogel, Jeffrey (2008)."Rotational and Radial Velocities for a Sample of 761 HIPPARCOS Giants and the Role of Binarity".The Astronomical Journal.135(1): 209–231.Bibcode:2008AJ....135..209M.doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/1/209.

- ^abPerryman; et al. (1997)."HIP 69673".The Hipparcos and Tycho Catalogues.

- ^abCarney, Bruce W.; et al. (March 2008). "Rotation and Macroturbulence in Metal-Poor Field Red Giant and Red Horizontal Branch Stars".The Astronomical Journal.135(3). Paris, France:EDP Sciences:892–906.arXiv:0711.4984.Bibcode:2008AJ....135..892C.doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/3/892.S2CID2756572.

- ^abcdefghijkRamírez, I.; Allende Prieto, C. (December 2011). "Fundamental Parameters and Chemical Composition of Arcturus".The Astrophysical Journal.743(2). Bristol, England:IOP Publishing:135.arXiv:1109.4425.Bibcode:2011ApJ...743..135R.doi:10.1088/0004-637X/743/2/135.S2CID119186472.

- ^Schröder, K.-P.; Cuntz, M. (April 2007). "A critical test of empirical mass loss formulas applied to individual giants and supergiants".Astronomy and Astrophysics.465(2). Bristol, England:IOP Publishing:593–601.arXiv:astro-ph/0702172.Bibcode:2007A&A...465..593S.doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066633.S2CID55901104.

- ^Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert."Ἀρκτοῦρος".A Greek-English Lexicon.Retrieved2019-01-16.

- ^Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert."ἄρκτος".A Greek-English Lexicon.Retrieved2019-01-16.

- ^Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert."οὖρος".A Greek-English Lexicon.Retrieved2019-01-16.

- ^"Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1"(PDF).Retrieved28 July2016.

- ^"IAU Catalog of Star Names".Retrieved28 July2016.

- ^Kaler, James B. (2002).The Hundred Greatest Stars.New York City: Copernicus Books. p. 21.ISBN978-0-387-95436-3.

- ^abcdeSchaaf, Fred (2008).The Brightest Stars: Discovering the Universe Through the Sky's Most Brilliant Stars.Hoboken, New Jersey:John Wiley and Sons.pp. 126–36.Bibcode:2008bsdu.book.....S.ISBN978-0-471-70410-2.

- ^Schaaf, p. 257.

- ^Rao, Joe (June 15, 2007)."Arc to Arcturus, Speed on to Spica".Space.com.Retrieved14 August2018.

- ^"Follow the arc to Arcturus, and drive a spike to Spica | EarthSky.org".earthsky.org.April 8, 2018.Retrieved14 August2018.

- ^abcRogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: II. The Mediterranean Traditions".Journal of the British Astronomical Association.108(2). London, England:British Astronomical Association:79–89.Bibcode:1998JBAA..108...79R.

- ^Ramya, P.; Reddy, Bacham E.; Lambert, David L. (2012). "Chemical compositions of stars in two stellar streams from the Galactic thick disc".Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.425(4): 3188.arXiv:1207.0767.Bibcode:2012MNRAS.425.3188R.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21677.x.S2CID119253279.

- ^Abia, C.; Palmerini, S.; Busso, M.; Cristallo, S. (2012). "Carbon and oxygen isotopic ratios in Arcturus and Aldebaran. Constraining the parameters for non-convective mixing on the red giant branch".Astronomy & Astrophysics.548:A55.arXiv:1210.1160.Bibcode:2012A&A...548A..55A.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220148.S2CID56386673.

- ^Lagarde, N.; et al. (August 2015). "Models of red giants in the CoRoT asteroseismology fields combining asteroseismic and spectroscopic constraints".Astronomy & Astrophysics.580:A141.arXiv:1505.01529.Bibcode:2015A&A...580A.141L.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525856.S2CID53652388.A141.

- ^Sennhauser, C.; Berdyugina, S. V. (May 2011)."First detection of a weak magnetic field on the giant Arcturus: remnants of a solar dynamo?".Astronomy & Astrophysics.529:6.Bibcode:2011A&A...529A.100S.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015445.A100.

- ^abPavlenko, Ya. V. (September 2008). "The carbon abundance and12C/13C isotopic ratio in the atmosphere of Arcturus from 2.3 µm CO bands ".Astronomy Reports.52(9): 749–759.arXiv:0807.3667.Bibcode:2008ARep...52..749P.doi:10.1134/S1063772908090060.S2CID119268407.

- ^Gray, R. O.; Corbally, C. J.; Garrison, R. F.; McFadden, M. T.; Robinson, P. E. (2003). "Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: Spectroscopy of Stars Earlier than M0 within 40 Parsecs: The Northern Sample. I".The Astronomical Journal.126(4). Bristol, England: 2048.arXiv:astro-ph/0308182.Bibcode:2003AJ....126.2048G.doi:10.1086/378365.S2CID119417105.

- ^Griffin, R. E.; Griffin, R. (1968).A photometric atlas of the spectrum of Arcturus, λλ3600-8825Å.Cambridge: Cambridge Philosophical Society.Bibcode:1968pmas.book.....G.

- ^abHinkle, K.; Wallace, L. (2005). "The Spectrum of Arcturus from the Infrared through the Ultraviolet".Cosmic Abundances as Records of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis.336:321.Bibcode:2005ASPC..336..321H.

- ^Tsuji, T. (2009). "The K giant star Arcturus: The hybrid nature of its infrared spectrum".Astronomy and Astrophysics.504(2): 543.arXiv:0907.0065.Bibcode:2009A&A...504..543T.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912323.S2CID6408779.

- ^Ohnaka, K.; Morales Marín, C. A. L. (November 2018). "Spatially resolving the thermally inhomogeneous outer atmosphere of the red giant Arcturus in the 2.3 μm CO lines".Astronomy & Astrophysics.620:10.arXiv:1809.01181.Bibcode:2018A&A...620A..23O.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833745.S2CID119095123.A23.

- ^Belmonte, J. A.; Jones, A. R.; Palle, P. L.; Roca Cortes, T. (1990). "Acoustic oscillations in the K2 III star Arcturus".Astrophysics and Space Science.169(1–2): 77–84.Bibcode:1990Ap&SS.169...77B.doi:10.1007/BF00640689.ISSN0004-640X.S2CID120697563.

- ^Kallinger, T.; Weiss, W. W.; Barban, C.; Baudin, F.; Cameron, C.; Carrier, F.; De Ridder, J.; Goupil, M.-J.; Gruberbauer, M.; Hatzes, A.; Hekker, S.; Samadi, R.; Deleuil, M. (2010). "Oscillating red giants in the CoRoT exofield: Asteroseismic mass and radius determination".Astronomy and Astrophysics.509:A77.arXiv:0811.4674.Bibcode:2010A&A...509A..77K.doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811437.S2CID15061735.

- ^Verhoelst, T.; Bordé, P. J.; Perrin, G.; Decin, L.; et al. (2005). "Is Arcturus a well-understood K giant?".Astronomy & Astrophysics.435(1): 289–301.arXiv:astro-ph/0501669.Bibcode:2005A&A...435..289V.doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042356.S2CID14176311.,and see references therein.

- ^Hatzes, A.; Cochran, W. (August 1993)."Long-period radial velocity variations in three K giants".The Astrophysical Journal.413(1): 339–348.Bibcode:1993ApJ...413..339H.doi:10.1086/173002.

- ^Eratosthenes; Hyginus; Aratus (2015).Eratosthenes and Hyginus: Constellation Myths, with Aratus's Phaenomena.Hard, Robin (transl.). Oxford University Press. pp. 5–7, 35–37.ISBN9780198716983.

- ^Ridpath, Ian."Star Tales Boötes".Retrieved27 November2022.

- ^Eratosthenes et al. (2015),pp. 38–40, p. 182 (note to p. 40)

- ^Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: I. The Mesopotamian Traditions".Journal of the British Astronomical Association.108(1): 9–28.Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- ^Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006).A Dictionary of Modern star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations(2nd rev. ed.).Cambridge,MA:Sky Pub.p. 19.ISBN978-1-931559-44-7.

- ^Knobel, E. B. (June 1895)."Al Achsasi Al Mouakket, on a catalogue of stars in the Calendarium of Mohammad Al Achsasi Al Mouakket".Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.55(8): 429.Bibcode:1895MNRAS..55..429K.doi:10.1093/mnras/55.8.429.

- ^"List of the 25 brightest stars".Jordanian Astronomical Society.Archived fromthe originalon March 16, 2012.RetrievedMarch 28,2007.

- ^Allen, Richard Hinckley (1936).Star-names and their meanings.pp. 100–101.

- ^Wehr, Hans (1994). Cowan, J. Milton (ed.).A dictionary of modern written Arabic.

- ^Davis Jr., G. A. (October 3, 1944). "The Pronunciations, Derivations, and Meanings of a Selected List of Star Names".Popular Astronomy.52:13.Bibcode:1944PA.....52....8D.

- ^Olcott, William Tyler (2004).Star Lore: Myths, Legends, and Facts.Mineola, New York: Dover Publications Inc. pp. 77–78.ISBN978-0-8021-4877-3.

- ^abNyoongah, Mudrooroo; Narogin, Mudrooroo (1994).Aboriginal mythology: an A-Z spanning the history of aboriginal mythology from the earliest legends to the present day.London: HarperCollins. p. 5.ISBN978-1-85538-306-7.

- ^Hamacher, Duane W.; Frew, David J. (2010). "An Aboriginal Australian Record of the Great Eruption of Eta Carinae".Journal of Astronomical History & Heritage.13(3): 220–34.arXiv:1010.4610.Bibcode:2010JAHH...13..220H.doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2010.03.06.S2CID118454721.

- ^abJohnson, Diane (1998).Night skies of aboriginal Australia: a noctuary.Darlington, New South Wales: University of Sydney. pp.24, 69, 84, 112.Bibcode:1998nsaa.book.....J.ISBN978-1-86451-356-1.

- ^Makemson, Maud Worcester (1941).The Morning Star Rises: an account of Polynesian astronomy.New Haven, Connecticut:Yale University Press.p. 199.Bibcode:1941msra.book.....M.

- ^Makemson 1941,p. 209.

- ^Makemson 1941,p. 280.

- ^Makemson 1941,p. 221.

- ^Makemson 1941,p. 264.

- ^Makemson 1941,p. 210.

- ^Makemson 1941,p. 260.

- ^"Arcturus".Constellation Guide.Retrieved20 June2017.

- ^Hagar, Stansbury (1900). "The Celestial Bear".The Journal of American Folklore.13(49): 92–103.doi:10.2307/533799.JSTOR533799.

- ^Daghavarian, Nazaret (1903).Ancient Armenian Religions (in Armenian)(PDF).p. 19.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2022-10-09.Retrieved12 February2021.

- ^Plautus."Rudens". p. prol. 71.

- ^abLewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879)."arctūrus".A Latin Dictionary.Oxford: Clarendon Press.Available on the Perseus Digital Library.

- ^Alan Roberts, Peter; Yeshi, Tulku (2013)."Karandavyuha Sutra Page 45"(PDF).Pacificbuddha.84000.

- ^Zimmer, Stefan (February 1, 2006).Die keltischen Wurzeln der Artussage: mit einer vollständigen Übersetzung der ältesten Artuserzählung Culhwch und Olwen(in German). Universitätsverlag. p. 37.ISBN978-3825351076.

- ^Zimmer, Stefan (March 2009). "The Name of Arthur – A New Etymology".Journal of Celtic Linguistics.13(1). University of Wales Press: 131–136.

- ^Walter, Philippe (2005).Artù. L'orso e il re(in Italian). Translated by Faccia, M. Edizioni Arkeios. p. 74.ISBN978-8886495806.

- ^Johnson, Flint (2002).The British sources of the abduction and Grail romances.University Press of America. pp. 38–39.ISBN978-0761822189.

- ^Chambers, Edmund Kerchever (1964).Arthur of Britain.Speculum Historiale. p. 170.

- ^Tyson, Donald; Freake, James (1993).Three Books of Occult Philosophy.Llewellyn Worldwide.ISBN978-0-87542-832-1.

- ^"The opening ceremony of A Century of Progress".Century of Progress World's Fair, 1933-1934.University of Illinois-Chicago. January 2008.Retrieved2022-08-28.

- ^Talcott, Rich (July 14, 2014)."Lincoln and the cosmos".Astronomy Magazine.Retrieved2022-08-28.

Further reading[edit]

- Harper, Graham M.; et al. (June 2022), "The Wind Temperature and Mass-loss Rate of Arcturus (K1.5 III)",The Astrophysical Journal,932(1): 57,Bibcode:2022ApJ...932...57H,doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac69d6,S2CID249880096,57.

- Isidoro-García, L.; et al. (January 2022), "Theoretical lifetimes and Stark broadening parameters for visible-infrared spectral lines of V I in Arcturus",Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society,509(3): 4538–4554,Bibcode:2022MNRAS.509.4538I,doi:10.1093/mnras/stab3301.

- Kushniruk, Iryna; Bensby, Thomas (November 2019), "Disentangling the Arcturus stream",Astronomy & Astrophysics,631:A47,arXiv:1909.04949,Bibcode:2019A&A...631A..47K,doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201935234,S2CID202558933,A47.

- Wood, M. P.; et al. (February 2018), "Vanadium Transitions in the Spectrum of Arcturus",The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series,234(2): 25,arXiv:1712.06942,Bibcode:2018ApJS..234...25W,doi:10.3847/1538-4365/aa9a41,S2CID119356096,25.

- Küker, M.; Rüdiger, G. (January 2011), "Differential rotation and meridional flow of Arcturus",Astronomische Nachrichten,332(1): 83,arXiv:1012.3321,Bibcode:2011AN....332...83K,doi:10.1002/asna.201011483.

- Lacour, S.; et al. (July 2008), "The limb-darkened Arcturus: imaging with the IOTA/IONIC interferometer",Astronomy and Astrophysics,485(2): 561–570,arXiv:0804.0192,Bibcode:2008A&A...485..561L,doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809611,S2CID18853087.

- Brown, Kevin I. T.; et al. (June 2008), "Long-Term Spectroscopic Monitoring of Arcturus",The Astrophysical Journal,679(2): 1531–1540,Bibcode:2008ApJ...679.1531B,doi:10.1086/587783,S2CID121170557.

- Tarrant, N. J.; et al. (November 2007), "Asteroseismology of red giants: photometric observations of Arcturus by SMEI",Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters,382(1): L48–L52,arXiv:0706.3346,Bibcode:2007MNRAS.382L..48T,doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2007.00387.x,S2CID5666311.

- Brown, Kevin I. T. (February 2007), "Long-Term Spectroscopic and Precise Radial Velocity Monitoring of Arcturus",The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific,119(852): 237,Bibcode:2007PASP..119..237B,doi:10.1086/512731,S2CID121637958.

- Gray, David F.; Brown, Kevin I. T. (August 2006), "The Rotation of Arcturus and Active Longitudes on Giant Stars",The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific,118(846): 1112–1118,Bibcode:2006PASP..118.1112G,doi:10.1086/507077,S2CID120918694.

- Cohen, Martin; et al. (June 2005), "Far-Infrared and Millimeter Continuum Studies of K Giants: α Bootis and α Tauri",The Astronomical Journal,129(6): 2836–2848,arXiv:astro-ph/0502516,Bibcode:2005AJ....129.2836C,doi:10.1086/429887,S2CID119419198.

- Navarro, Julio F.; et al. (January 2004), "The Extragalactic Origin of the Arcturus Group",The Astrophysical Journal,601(1): L43–L46,arXiv:astro-ph/0311107,Bibcode:2004ApJ...601L..43N,doi:10.1086/381751,S2CID10638792.

- Retter, Alon; et al. (July 2003), "Oscillations in Arcturus from WIRE Photometry",The Astrophysical Journal,591(2): L151–L154,arXiv:astro-ph/0306056,Bibcode:2003ApJ...591L.151R,doi:10.1086/377211,S2CID119083930.

- Ryde, N.; et al. (November 2002), "Detection of Water Vapor in the Photosphere of Arcturus",The Astrophysical Journal,580(1): 447–458,arXiv:astro-ph/0207368,Bibcode:2002ApJ...580..447R,doi:10.1086/343040,S2CID7672420.

- Griffin, R. E. M.; Lynas-Gray, A. E. (June 1999), "The Effective Temperature of Arcturus",The Astronomical Journal,117(6): 2998–3006,Bibcode:1999AJ....117.2998G,doi:10.1086/300878,S2CID120907426.

- Turner, Nils H.; et al. (May 1999), "Adaptive Optics Observations of Arcturus using the Mount Wilson 100 Inch Telescope",The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific,111(759): 556–558,Bibcode:1999PASP..111..556T,doi:10.1086/316353,S2CID2441153.

- Griffin, R. F. (October 1998), "Arcturus as a double star",The Observatory,118:299–301,Bibcode:1998Obs...118..299G.

- Quirrenbach, A.; et al. (August 1996), "Angular diameter and limb darkening of Arcturus.",Astronomy and Astrophysics,312:160–166,Bibcode:1996A&A...312..160Q.

External links[edit]