Baltimore

Baltimore[a]is themost populous cityin theU.S. stateofMaryland.With a population of 585,708 at the2020 census,it is the30th-most populous cityin the United States.[15]Baltimore was designated anindependent cityby theConstitution of Maryland[b]in 1851, and is currently the most populous independent city in the nation. As of the 2020 census, the population of theBaltimore metropolitan areawas 2,838,327, the20th-largest metropolitan areain the country.[16]When combined with the largerWashington metropolitan area,theWashington–Baltimore combined statistical area(CSA) has a 2020 U.S. census population of 9,973,383, the third-largest in the country.[16]Though the city is not located within or under the administrative jurisdiction of any county in the state, it is considered to be part of the Central Maryland region, together withthe surrounding county that shares its name.

The land that is present-day Baltimore was used as hunting ground byPaleo-Indians.In the early 1600s, theSusquehannockbegan to hunt there.[17]People from theProvince of Marylandestablished thePort of Baltimorein 1706 to support thetobaccotrade with Europe, and established the Town of Baltimore in 1729.

In the mid-18th century, the first printing press and newspapers were introduced to Baltimore byNicholas HasselbachandWilliam Goddard.During theAmerican Revolutionary War,theSecond Continental Congress,fleeingPhiladelphiaprior to thecity's fall to British troops,moved their deliberations toHenry Fite Houseon West Baltimore Street from December 20, 1776, to February 27, 1777, permitting Baltimore to serve briefly asthe nation's capitalbefore the capital returned toIndependence Hallin Philadelphia on March 5, 1777.

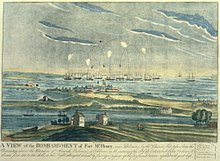

TheBattle of Baltimorewas a pivotal engagement during theWar of 1812,culminating in the failedBritishbombardment ofFort McHenry,during whichFrancis Scott Keywrote a poem that would become "The Star-Spangled Banner",which was eventually designated as the American national anthem in 1931.[18]During thePratt Street Riot of 1861,the city was the site of some of the earliest violence associated with theAmerican Civil War.

TheBaltimore and Ohio Railroad,the nation's oldest railroad, was built in 1830 and cemented Baltimore's status as a major transportation hub, giving producers in theMidwestandAppalachiaaccess to the city'sport.Baltimore'sInner Harborwas once the second leadingport of entryforimmigrantsto the United States. In addition, Baltimore was a majormanufacturingcenter.[19]After a decline in major manufacturing,heavy industry,and restructuring of therail industry,Baltimore has shifted to aservice-oriented economy.Johns Hopkins HospitalandJohns Hopkins Universityare the city's top two employers.[20]Baltimore and its surrounding region are home to the headquarters of a number of major organizations and government agencies, including theNAACP,ABET,theNational Federation of the Blind,Catholic Relief Services,theAnnie E. Casey Foundation,World Relief,theCenters for Medicare & Medicaid Services,and theSocial Security Administration.Baltimore is also home to theBaltimore OriolesofMajor League Baseballand theBaltimore Ravensof theNational Football League.

Many of Baltimore's neighborhoods have rich histories. The city is home to some of the earliestNational Register Historic Districtsin the nation, includingFell's Point,Federal Hill,andMount Vernon.These were added to theNational Registerbetween 1969 and 1971, soon after historic preservation legislation was passed. Baltimore has more public statues and monuments per capita than any other city in the country.[21]Nearly one third of the city's buildings (over 65,000) are designated as historic in the National Register, which is more than any other U.S. city.[22][23]Baltimore has 66National Register Historic Districtsand 33 local historic districts.[22]The historical records of the government of Baltimore are located at theBaltimore City Archives.

History

[edit]Pre-settlement

[edit]The Baltimore area had been inhabited byNative Americanssince at least the10th millennium BC,whenPaleo-Indiansfirst settled in the region.[24]One Paleo-Indian site and severalArchaic periodandWoodland periodarchaeological sites have been identified in Baltimore, including four from theLate Woodland period.[24]In December 2021, several Woodland period Native American artifacts were found inHerring Run Parkin northeast Baltimore, dating 5,000 to 9,000 years ago. The finding followed a period of dormancy in Baltimore City archaeological findings which had persisted since the 1980s.[25]During the Late Woodland period, thearchaeological cultureknown as the Potomac Creek complex resided in the area from Baltimore south to theRappahannock Riverin present-dayVirginia.[26]

Etymology

[edit]The city is named afterCecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore,[27]an English peer, member of theIrish House of Lordsand founding proprietor of theProvince of Maryland.[28][29]The Calverts took the titleBarons BaltimorefromBaltimore Manor,an EnglishPlantation estatethey were granted inCounty Longford,Ireland.[29][30]Baltimore is ananglicizationof theIrishnameBaile an Tí Mhóir,meaning "town of the big house".[29]

17th century

[edit]In the early 1600s, the immediate Baltimore vicinity was sparsely populated, if at all, by Native Americans. The Baltimore County area northward was used as hunting grounds by theSusquehannockliving in the lowerSusquehanna Rivervalley. ThisIroquoian-speaking people"controlled all of the upper tributaries of the Chesapeake" but "refrained from much contact withPowhatanin thePotomac region"and south into Virginia.[31] Pressured by the Susquehannock, thePiscataway tribe,anAlgonquian-speaking people,stayed well south of the Baltimore area and inhabited primarily the north bank of thePotomac Riverin what are nowCharlesand southernPrince George'scounties in the coastal areas south of theFall Line.[32][33][34]

European colonizationof Maryland began in earnest with the arrival of the merchant shipThe Arkcarrying 140 colonists at St. Clement's Island in thePotomac Riveron March 25, 1634.[35]Europeans then began to settle the area further north, in what is nowBaltimore County.[36]Since Maryland was a colony, Baltimore's streets were named to show loyalty to the mother country, e.g. King, Queen, King George and Caroline streets.[37]The originalcounty seat,known today as Old Baltimore, was located onBush Riverwithin the present-dayAberdeen Proving Ground.[38][39][40]The colonists engaged in sporadic warfare with the Susquehannock, whose numbers dwindled primarily from new infectious diseases, such assmallpox,endemic among the Europeans.[36]In 1661 David Jones claimed the area known today asJonestownon the east bank of theJones Fallsstream.[41]

18th century

[edit]

The colonialGeneral Assembly of Marylandcreated thePort of Baltimoreat old Whetstone Point, nowLocust Point,in 1706 for thetobacco trade.The Town of Baltimore, on the west side of the Jones Falls, was founded on August 8, 1729, when the Governor of Maryland signed an act allowing "the building of a Town on the North side of the Patapsco River." Surveyors began laying out the town on January 12, 1730. By 1752 the town had just 27 homes, including a church and two taverns.[37]Jonestown and Fells Point had been settled to the east. The three settlements, covering 60 acres (24 ha), became a commercial hub, and in 1768 were designated as the county seat.[42]

The first printing press was introduced to the city in 1765 byNicholas Hasselbach,whose equipment was later used in the printing of Baltimore's first newspapers,The Maryland JournalandThe Baltimore Advertiser,first published byWilliam Goddardin 1773.[43][44][45]

Baltimore grew swiftly in the 18th century, its plantations producing grain and tobacco forsugar-producing colonies in the Caribbean.The profit from sugar encouraged the cultivation of cane in the Caribbean and the importation of food by planters there.[46]Since Baltimore was the county seat, a courthouse was built in 1768 to serve both the city and county. Its square was a center of community meetings and discussions.

Baltimore established itspublic market systemin 1763.[47]Lexington Market,founded in 1782, is one of the oldest continuously operating public markets in the United States today.[48]Lexington Market was also a center of slave trading. Enslaved Black people were sold at numerous sites through the downtown area, with sales advertised inThe Baltimore Sun.[49]Both tobacco and sugar cane were labor-intensive crops.

In 1774, Baltimore established the first post office system in what became the United States,[50]and the first water company chartered in the newly independent nation, Baltimore Water Company, 1792.[51][52]

Baltimore played a part in theAmerican Revolution.City leaders such asJonathan Plowman Jr.led many residents toresist British taxes,and merchants signed agreements refusing to trade with Britain.[53]TheSecond Continental Congressmet in theHenry Fite Housefrom December 1776 to February 1777, effectively making the city thecapital of the United Statesduring this period.[54]

Baltimore,Jonestown,andFells Pointwereincorporatedas the City of Baltimore in 1796–1797.

19th century

[edit]

The city remained a part of surroundingBaltimore Countyand continued to serve as its county seat from 1768 to 1851, after which it became anindependent city.[57]

TheBattle of Baltimoreagainst the British in 1814 inspired the U.S. national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner",and the construction of theBattle Monument,which became the city's official emblem. A distinctive local culture started to take shape, and a unique skyline peppered with churches and monuments developed. Baltimore acquired its moniker "The Monumental City" after an 1827 visit to Baltimore by PresidentJohn Quincy Adams.At an evening function, Adams gave the following toast: "Baltimore: the Monumental City—May the days of her safety be as prosperous and happy, as the days of her dangers have been trying and triumphant."[58][59]

Baltimore pioneered the use ofgas lightingin 1816, and its population grew rapidly in the following decades, with concomitant development of culture and infrastructure. The construction of the federally fundedNational Road,which later became part ofU.S. Route 40,and the privateBaltimore and Ohio Railroad(B. & O.) made Baltimore a major shipping andmanufacturingcenter by linking the city with major markets in theMidwest.By 1820 its population had reached 60,000, and its economy had shifted from its base in tobacco plantations tosawmilling,shipbuilding,andtextileproduction. These industries benefited from war but successfully shifted intoinfrastructuredevelopment during peacetime.[60]

Baltimore had one of the worst riots of the antebellumSouthin 1835, when bad investments led to theBaltimore bank riot.[61]It was these riots that led to the city beingnicknamed"Mobtown".[62]Soon after the city created the world's first dental college, theBaltimore College of Dental Surgery,in 1840, and shared in theworld's first telegraph line,between Baltimore andWashington, D.C.,in 1844.

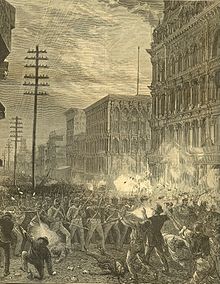

Maryland, aslave statewith limited popular support forsecession,especially in the three counties of Southern Maryland, remained part of theUnionduring theAmerican Civil War,following the 55–12 vote by the Maryland General Assembly against secession. Later, the Union's strategic occupation of the city in 1861 ensured Maryland would not further consider secession.[63][64]The Union's capital of Washington, D.C. was well-situated to impede Baltimore and Maryland's communication or commerce with theConfederacy.Baltimore experienced some of the first casualties of Civil War on April 19, 1861, whenUnion Armysoldiers en route fromPresident Street StationtoCamden Yardsclashed with a secessionist mob in thePratt Street riot.

In the midst of theLong Depressionthat followed thePanic of 1873,theBaltimore and Ohio Railroadcompany attempted to lower its workers' wages, leading tostrikes and riotsin the city andbeyond.Strikers clashed with theNational Guard,leaving 10 dead and 25 wounded.[65]The beginnings ofsettlement movementwork in Baltimore were made early in 1893, when Rev. Edward A. Lawrence took up lodgings with his friend Frank Thompson, in one of theWinanstenements, theLawrence Housebeing established shortly thereafter at 814-816 West Lombard Street.[66][67]

20th century

[edit]

On February 7, 1904, theGreat Baltimore Firedestroyed over 1,500 buildings in 30 hours, leaving more than 70 blocks of the downtown area burned to the ground. Damages were estimated at $150 million in 1904 dollars.[68]As the city rebuilt during the next two years, lessons learned from the fire led to improvements in firefighting equipment standards.[69]

Baltimore lawyer Milton Dashiell advocated for an ordinance to bar African-Americans from moving into theEutaw Placeneighborhood in northwest Baltimore. He proposed to recognize majority white residential blocks and majority black residential blocks and to prevent people from moving into housing on such blocks where they would be a minority. The Baltimore Council passed the ordinance, and it became law on December 20, 1910, with DemocraticMayor J. Barry Mahool's signature.[70]The Baltimore segregation ordinance was the first of its kind in the United States. Many other southern cities followed with their own segregation ordinances, though the US Supreme Court ruled against them inBuchanan v. Warley(1917).[71]

The city grew in area by annexing new suburbs from the surrounding counties through 1918, when the city acquired portions of Baltimore County andAnne Arundel County.[72]A state constitutional amendment, approved in 1948, required a special vote of the citizens in any proposed annexation area, effectively preventing any future expansion of the city's boundaries.[73]Streetcarsenabled the development of distant neighborhoods areas such asEdmonson Villagewhose residents could easily commute to work downtown.[74]

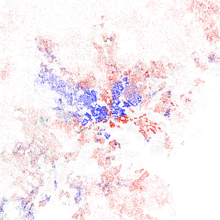

Driven by migration from thedeep Southand bywhite suburbanization,the relative size of the city'sblackpopulation grew from 23.8% in 1950 to 46.4% in 1970.[75]Encouraged by real estateblockbustingtechniques, recently settled white areas rapidly became all-black neighborhoods, in a rapid process which was nearly total by 1970.[76]

TheBaltimore riot of 1968,coinciding withuprisings in other cities,followed theassassination of Martin Luther King Jr.on April 4, 1968. Public order was not restored until April 12, 1968. The Baltimore uprising cost the city an estimated $10 million (US$ 88 million in 2024). A total of 12,000 Maryland National Guard and federal troops were ordered into the city.[77]The city experienced challenges again in 1974 when teachers,municipal workers,andpolice officersconducted strikes.[78]

By the beginning of the 1970s, Baltimore's downtown area, known as the Inner Harbor, had been neglected and was occupied by a collection of abandoned warehouses. The nickname "Charm City" came from a 1975 meeting of advertisers seeking to improve the city's reputation.[79][80]Efforts to redevelop the area started with the construction of theMaryland Science Center,which opened in 1976, theBaltimore World Trade Center(1977), and theBaltimore Convention Center(1979).Harborplace,an urban retail and restaurant complex, opened on the waterfront in 1980, followed by theNational Aquarium,Maryland's largest tourist destination, and theBaltimore Museum of Industryin 1981. In 1995, the city opened theAmerican Visionary Art Museumon Federal Hill. During theepidemic of HIV/AIDS in the United States,Baltimore City Health Departmentofficial Robert Mehl persuaded the city's mayor to form a committee to address food problems. The Baltimore-based charityMoveable Feastgrew out of this initiative in 1990.[81][82][83]

In 1992, theBaltimore Oriolesbaseball teammoved fromMemorial StadiumtoOriole Park at Camden Yards,located downtown near the harbor.Pope John Paul IIheld an open-air mass at Camden Yards during his papal visit to the United States in October 1995. Three years later theBaltimore Ravensfootball teammoved intoM&T Bank Stadiumnext to Camden Yards.[84]

Baltimore has had ahigh homicide ratefor several decades, peaking in 1993, and again in 2015.[85][86]These deaths have taken an especially severe toll within the black community.[87]Following thedeath of Freddie Grayin April 2015, the city experiencedmajor protestsand international media attention, as well as a clash between local youth and police that resulted in astate of emergencydeclaration and a curfew.[88]

21st century

[edit]Baltimore has seen the reopening of theHippodrome Theatrein 2004,[89]the opening of theReginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culturein 2005, and the establishment of theNational Slavic Museumin 2012. On April 12, 2012, Johns Hopkins held a dedication ceremony to mark the completion of one of the United States' largest medical complexes – the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore – which features the Sheikh Zayed Cardiovascular and Critical Care Tower and The Charlotte R. Bloomberg Children's Center. The event, held at the entrance to the $1.1 billion 1.6 million-square-foot-facility, honored the many donors includingSheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan,first president of theUnited Arab Emirates,andMichael Bloomberg.[90][91]

In September 2016, the Baltimore City Council approved a $660 million bond deal for the $5.5 billionPort Covingtonredevelopment project championed byUnder ArmourfounderKevin Plankand his real estate company Sagamore Development. Port Covington surpassed the Harbor Point development as the largesttax-increment financingdeal in Baltimore's history and among the largest urban redevelopment projects in the country.[92]The waterfront development that includes the new headquarters for Under Armour, as well as shops, housing, offices, and manufacturing spaces is projected to create 26,500 permanent jobs with a $4.3 billion annual economic impact.[93]Goldman Sachsinvested $233 million into the redevelopment project.[94]

In the early hours of March 26, 2024, the city's 1.6-mile-long (2.6 km)Francis Scott Key Bridge,which constituted a southeast portion of theBaltimore Beltway,was struck by a container ship andcompletely collapsed.A major rescue operation was launched with US authorities attempting to rescue people in the water.[95] Eight construction workers, who were working on the bridge at the time, fell into thePatapsco River.[96]Two people were rescued from the water,[97]and the bodies of the remaining six were all found by May 7.[98]Replacement of the bridgewas estimated in May 2024 at a cost approaching $2 billion for a fall 2028 completion.[99]

Geography

[edit]Baltimore is in north-central Maryland on thePatapsco River,close to where it empties into theChesapeake Bay.The city is located on thefall linebetween thePiedmontPlateau and theAtlantic coastal plain,which divides Baltimore into "lower city" and "upper city". The city's elevation ranges from sea level at the harbor to 480 feet (150 m) in the northwest corner nearPimlico.[6]

According to the 2010 census, the city has a total area of 92.1 square miles (239 km2), of which 80.9 sq mi (210 km2) is land and 11.1 sq mi (29 km2) is water.[100]The total area is 12.1 percent water.

Baltimore is almost surrounded by Baltimore County, but ispolitically independentof it. It is bordered byAnne Arundel Countyto the south.

Cityscape

[edit]Architecture

[edit]

Baltimore exhibits examples from each period of architecture over more than two centuries, and work from architects such asBenjamin Latrobe,George A. Frederick,John Russell Pope,Mies van der Rohe,andI. M. Pei.

Baltimore is rich in architecturally significant buildings in a variety of styles. TheBaltimore Basilica(1806–1821) is a neoclassical design by Benjamin Latrobe, and one of the oldestCatholiccathedrals in the United States. In 1813, Robert Cary Long Sr. built forRembrandt Pealethe first substantial structure in the United States designed expressly as a museum. Restored, it is now the Municipal Museum of Baltimore, or popularly thePeale Museum.

TheMcKim Free Schoolwas founded and endowed by John McKim. The building was erected by his sonIsaacin 1822 after a design by William Howard and William Small. It reflects the popular interest inGreecewhen the nation was securing its independence and a scholarly interest in recently published drawings of Athenian antiquities.

ThePhoenix Shot Tower(1828), at 234.25 feet (71.40 m) tall, was the tallest building in the United States until the time of the Civil War, and is one of few remaining structures of its kind.[101]It was constructed without the use of exterior scaffolding. The Sun Iron Building, designed by R.C. Hatfield in 1851, was the city's first iron-front building and was a model for a whole generation of downtown buildings.Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church,built in 1870 in memory of financierGeorge Brown,hasstained glasswindows byLouis Comfort Tiffanyand has been called "one of the most significant buildings in this city, a treasure of art and architecture" byBaltimoremagazine.[102][103]

The 1845Greek Revival-styleLloyd Street Synagogueis one of theoldest synagogues in the United States.TheJohns Hopkins Hospital,designed byLt. Col. John S. Billingsin 1876, was a considerable achievement for its day in functional arrangement and fireproofing.

I.M. Pei'sWorld Trade Center(1977) is the tallest equilateral pentagonal building in the world at 405 feet (123 m) tall.

TheHarbor Eastarea has seen the addition of two new towers which have completed construction: a 24-floor tower that is the new world headquarters ofLegg Mason,and a 21-floorFour Seasons Hotelcomplex.

The streets of Baltimore are organized in a grid and spoke pattern, lined with tens of thousands ofrowhouses.The mix of materials on the face of these rowhouses also give Baltimore its distinct look. The rowhouses are a mix of brick and formstone facings, the latter a technology patented in 1937 by Albert Knight.John Waterscharacterized formstone as "the polyester of brick" in a 30-minute documentary film,Little Castles: A Formstone Phenomenon.[104]InThe Baltimore Rowhouse,Mary Ellen Hayward andCharles Belfoureconsidered the rowhouse as the architectural form defining Baltimore as "perhaps no other American city".[105]In the mid-1790s, developers began building entire neighborhoods of the British-style rowhouses, which became the dominant house type of the city early in the 19th century.[106]

Oriole Park at Camden Yardsis aMajor League Baseballpark, which opened in 1992 and was built as aretro stylebaseball park. Along with the National Aquarium, Camden Yards have helped revive the Inner Harbor area from what once was an exclusivelyindustrial districtfull of dilapidated warehouses into a bustling commercial district full of bars, restaurants, and retail establishments.

After an international competition, theUniversity of Baltimore School of Lawawarded theGermanfirmBehnisch Architekten1st prize for its design, which was selected for the school's new home. After the building's opening in 2013, the design won additional honors including an ENR National "Best of the Best" Award.[107]

Baltimore's newly rehabilitatedEveryman Theatrewas honored by the Baltimore Heritage at the 2013 Preservation Awards Celebration in 2013. Everyman Theatre will receive an Adaptive Reuse and Compatible Design Award as part of Baltimore Heritage's 2013 historic preservation awards ceremony. Baltimore Heritage is Baltimore's nonprofit historic and architectural preservation organization, which works to preserve and promote Baltimore's historic buildings and neighborhoods.[108]

Tallest buildings

[edit]| Rank | Building | Height | Floors | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Transamerica Tower(formerly the Legg Mason Building, originally built as the U.S. Fidelity and Guarantee Co. Building)[109] | 529 feet (161 m) | 40 | 1973 | [110] |

| 2 | Bank of America Building(originally built as Baltimore Trust Building, later Sullivan, Mathieson, Md. Nat. Bank, NationsBank Bldgs.) | 509 feet (155 m) | 37 | 1929 | [111] |

| 3 | 414 Light Street | 500 feet (152 m) | 44 | 2018 | [112] |

| 4 | William Donald Schaefer Tower(originally built as the Merritt S. & L. Tower) | 493 feet (150 m) | 37 | 1992 | [113] |

| 5 | Commerce Place(Alex. Brown & Sons/Deutsche Bank Tower) | 454 feet (138 m) | 31 | 1992 | [114] |

| 6 | Baltimore Marriott Waterfront Hotel | 430 feet (131 m) | 32 | 2001 | [115] |

| 7 | 100 East Pratt Street(originally built as the I.B.M. Building) | 418 feet (127 m) | 28 | 1975/1992 | [116] |

| 8 | Baltimore World Trade Center | 405 feet (123 m) | 28 | 1977 | [117] |

| 9 | Tremont Plaza Hotel | 395 feet (120 m) | 37 | 1967 | [118] |

| 10 | Charles Towers South | 385 feet (117 m) | 30 | 1969 | [119] |

Neighborhoods

[edit]

Baltimore is officially divided into nine geographical regions: North, Northeast, East, Southeast, South, Southwest, West, Northwest, and Central, with each district patrolled by a respectiveBaltimore Police Department.Interstate 83andCharles Streetdown toHanover StreetandRitchie Highwayserve as the east–west dividing line andEastern AvenuetoRoute 40as the north–south dividing line; however,Baltimore Streetis north–south dividing line for theU.S. Postal Service.[120]

Central Baltimore

[edit]Central Baltimore, originally called the Middle District,[121]stretches north of the Inner Harbor up to the edge ofDruid Hill Park.Downtown Baltimore has mainly served as a commercial district with limited residential opportunities; however, between 2000 and 2010, the downtown population grew 130 percent as old commercial properties have been replaced by residential property.[122]Still the city's main commercial area and business district, it includes Baltimore's sports complexes:Oriole Park at Camden Yards,M&T Bank Stadium,and theRoyal Farms Arena;and the shops and attractions in the Inner Harbor:Harborplace,theBaltimore Convention Center,theNational Aquarium,Maryland Science Center,Pier Six Pavilion,andPower Plant Live.[120]

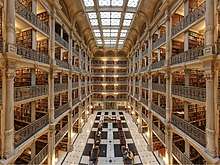

TheUniversity of Maryland, Baltimore,theUniversity of Maryland Medical Center,andLexington Marketare also in the central district, as well as theHippodromeand many nightclubs, bars, restaurants, shopping centers and various other attractions.[120][121]The northern portion of Central Baltimore, between downtown and the Druid Hill Park, is home to many of the city's cultural opportunities.Maryland Institute College of Art,thePeabody Institute(music conservatory),George Peabody Library,Enoch Pratt Free Library– Central Library, theLyric Opera House,theJoseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall,theWalters Art Museum,theMaryland Center for History and Cultureand itsEnoch PrattMansion, and several galleries are located in this region.[123]

North Baltimore

[edit]

Several historic and notable neighborhoods are in this district:Govans(1755),Roland Park(1891),Guilford(1913),Homeland(1924),Hampden,Woodberry,Old Goucher(the original campus ofGoucher College), andJones Falls.Along theYork Roadcorridor going north are the large neighborhoods ofCharles Village,Waverly,andMount Washington.TheStation North Arts and Entertainment Districtis also located in North Baltimore.[124]

South Baltimore

[edit]

South Baltimore, a mixed industrial and residential area, consists of the "Old South Baltimore" peninsula below the Inner Harbor and east of the oldB&O Railroad's Camden line tracks andRussell Streetdowntown. It is a culturally, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse waterfront area with neighborhoods such asLocust Pointand Riverside around a large park of the same name.[125]Just south of the Inner Harbor, the historicFederal Hillneighborhood, is home to many working professionals, pubs and restaurants. At the end of the peninsula is historicFort McHenry,a National Park since the end of World War I, when the old U.S. Army Hospital surrounding the 1798 star-shaped battlements was torn down.[126]

Across the Hanover Street Bridge are residential areas such asCherry Hill.[127]

Northeast Baltimore

[edit]Northeast is primarily a residential neighborhood, home toMorgan State University,bounded by the city line of 1919 on its northern and eastern boundaries,Sinclair Lane,Erdman Avenue,andPulaski Highwayto the south andThe Alamedaon to the west. Also in this wedge of the city on33rd StreetisBaltimore City Collegehigh school, third oldest active public secondary school in the United States, founded downtown in 1839.[128]AcrossLoch Raven Boulevardis the former site of the oldMemorial Stadiumhome of theBaltimore Colts,Baltimore Orioles,andBaltimore Ravens,now replaced by aYMCAathletic and housing complex.[129][130]Lake Montebellois in Northeast Baltimore.[121]

East Baltimore

[edit]Located belowSinclair LaneandErdman Avenue,aboveOrleans Street,East Baltimore is mainly made up of residential neighborhoods. This section of East Baltimore is home toJohns Hopkins Hospital,Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine,andJohns Hopkins Children's CenteronBroadway.Notable neighborhoods include:Armistead Gardens,Broadway East,Barclay,Ellwood Park,Greenmount,andMcElderry Park.[121]

This area was the on-site film location forHomicide: Life on the Street,The CornerandThe Wire.[131]

Southeast Baltimore

[edit]Southeast Baltimore, located belowFayette Street,bordering the Inner Harbor and the Northwest Branch of thePatapsco Riverto the west, the city line of 1919 on its eastern boundaries and the Patapsco River to the south, is a mixed industrial and residential area.Patterson Park,the "Best Backyard in Baltimore",[132]as well as theHighlandtown Arts District,andJohns Hopkins Bayview Medical Centerare located in Southeast Baltimore. The Shops at Canton Crossing opened in 2013.[133]TheCantonneighborhood, is located along Baltimore's prime waterfront. Other historic neighborhoods include:Fells Point,Patterson Park,Butchers Hill,Highlandtown,Greektown,Harbor East,Little Italy,andUpper Fell's Point.[121]

Northwest Baltimore

[edit]Northwestern is bounded by the county line to the north and west,Gwynns Falls Parkwayon the south andPimlico Roadon the east, is home toPimlico Race Course,Sinai Hospital,and the headquarters of theNAACP.Its neighborhoods are mostly residential and are dissected byNorthern Parkway.The area has been the center ofBaltimore's Jewish communitysince after World War II. Notable neighborhoods include:Pimlico,Mount Washington,andCheswolde,andPark Heights.[134]

West Baltimore

[edit]West Baltimore is west of downtown and theMartin Luther King Jr. Boulevardand is bounded by Gwynns Falls Parkway,Fremont Avenue,andWest Baltimore Street.TheOld West Baltimore Historic Districtincludes the neighborhoods ofHarlem Park,Sandtown-Winchester,Druid Heights,Madison Park,andUpton.[135][136]Originally a predominantly German neighborhood, by the last half of the 19th century, Old West Baltimore was home to a substantial section of the city's Black population.[135]

It became the largest neighborhood for the city's Black community and its cultural, political, and economic center.[135]Coppin State University,Mondawmin Mall,andEdmondson Villageare located in this district. The area's crime problems have provided subject material for television series, such asThe Wire.[137]Local organizations, such as the Sandtown Habitat for Humanity and the Upton Planning Committee, have been steadily transforming parts of formerly blighted areas of West Baltimore into clean, safe communities.[138][139]

Southwest Baltimore

[edit]Southwest Baltimore is bound by the Baltimore County line to the west, WestBaltimore Streetto the north, andMartin Luther King Jr. BoulevardandRussell Street/Baltimore-Washington Parkway(Maryland Route 295) to the east. Notable neighborhoods in Southwest Baltimore include:Pigtown,Carrollton Ridge,Ridgely's Delight,Leakin Park,Violetville,Lakeland,andMorrell Park.[121]

St. Agnes HospitalonWilkensandCaton[121]avenues is located in this district with the neighboringCardinal Gibbons High School,which is the former site ofBabe Ruth's alma mater, St. Mary's Industrial School.[citation needed]Through this segment of Baltimore ran the beginnings of the historicNational Road,which was constructed beginning in 1806 alongOld Frederick Roadand continuing into the county onFrederick RoadintoEllicott City, Maryland.[citation needed]Other sides in this district are:Carroll Park,one of the city's largest parks, the colonial Mount Clare Mansion, andWashington Boulevard,which dates to pre-Revolutionary War days as the prime route out of the city toAlexandria, Virginia,andGeorgetownon thePotomac River.[citation needed]

Adjacent communities

[edit]Baltimore is bordered by the following communities, all unincorporatedcensus-designated places.

Climate

[edit]

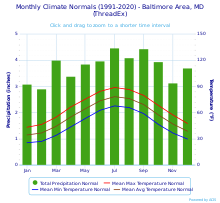

Baltimore has ahumid subtropical climate(Cfa) in theKöppen climate classification,with hot summers, cool winters, and a summer peak to annual precipitation.[140][141]Baltimore is part of USDA planthardiness zones7b and 8a.[142]Summers are normally warm, with occasional late day thunderstorms. July, the warmest month, has a mean temperature of 80.3 °F (26.8 °C). Winters range from chilly to mild but vary, with sporadic snowfall: January has a daily average of 35.8 °F (2.1 °C),[143]though temperatures reach 50 °F (10 °C) quite often, and can occasionally drop below 20 °F (−7 °C) when Arctic air masses affect the area.[143]According toVox,winters are warming faster than summers.[141]

Spring and autumn are mild, with spring being the wettest season in terms of the number of precipitation days. Summers are hot and humid with a daily average in July of 80.7 °F (27.1 °C).[143]The combination of heat and humidity leads to occasional thunderstorms. A southeasterly bay breeze off the Chesapeake often occurs on summer afternoons when hot air rises over inland areas. Prevailing winds from the southwest interacting with this breeze as well as the city proper's UHI can seriously exacerbate air quality.[144][145]In late summer and early autumn the track of hurricanes or their remnants may cause flooding in downtown Baltimore, despite the city being far removed from the typical coastalstorm surgeareas.[146]

The average seasonal snowfall is 19 inches (48 cm).[147]It varies greatly by year, with some seasons seeing only trace accumulations of snow, while others see several majorNor'easters.[c]Owing to lessenedurban heat island(UHI) as compared to thecity properand distance from the moderating Chesapeake Bay, the outlying and inland parts of the Baltimore metro area are usually cooler, especially at night, than the city proper and the coastal towns. Thus, in the northern and western suburbs, winter snowfall is more significant, and some areas average more than 30 in (76 cm) of snow per winter.[149]

It is by not uncommon for the rain-snow line to set up in the metro area.[150]Freezing rainand sleet occur a few times some winters in the area, as warm air overrides cold air at the low to mid-levels of the atmosphere. When the wind blows from the east, the cold air getsdammed against the mountainsto the west and the result is freezing rain or sleet.

Likeall of Maryland,Baltimore is at risk for increased impacts ofclimate change.Historically, flooding has ruined houses and almost killed people, especially in lower income majority Black neighborhoods, and caused sewage backups, given the existing disrepair of Baltimore's water system.[151]

Extreme temperatures range from −7 °F (−22 °C) on February 9, 1934, andFebruary 10, 1899,[d]up to 108 °F (42 °C) on July 22, 2011.[152][153]On average, temperatures of 100 °F (38 °C) or more occur on three days annually, 90 °F (32 °C) or more on 43 days, and there are nine days where the high fails to reach the freezing mark.[143]

| Climate data for Baltimore (Baltimore/Washington International Airport) 1991−2020 normals,[e]extremes 1872–present[f]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

83 (28) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

105 (41) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

86 (30) |

77 (25) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 64.6 (18.1) |

66.4 (19.1) |

75.9 (24.4) |

85.8 (29.9) |

91.0 (32.8) |

95.9 (35.5) |

98.0 (36.7) |

95.9 (35.5) |

91.1 (32.8) |

83.8 (28.8) |

74.3 (23.5) |

66.0 (18.9) |

98.9 (37.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43.2 (6.2) |

46.4 (8.0) |

54.8 (12.7) |

66.5 (19.2) |

75.5 (24.2) |

84.4 (29.1) |

88.8 (31.6) |

86.5 (30.3) |

79.7 (26.5) |

68.3 (20.2) |

57.3 (14.1) |

47.5 (8.6) |

66.6 (19.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 34.3 (1.3) |

36.6 (2.6) |

44.3 (6.8) |

55.0 (12.8) |

64.4 (18.0) |

73.5 (23.1) |

78.3 (25.7) |

76.2 (24.6) |

69.2 (20.7) |

57.4 (14.1) |

46.9 (8.3) |

38.6 (3.7) |

56.2 (13.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 25.4 (−3.7) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

33.9 (1.1) |

43.6 (6.4) |

53.3 (11.8) |

62.6 (17.0) |

67.7 (19.8) |

65.8 (18.8) |

58.8 (14.9) |

46.5 (8.1) |

36.5 (2.5) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

45.9 (7.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 9.1 (−12.7) |

12.2 (−11.0) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

38.8 (3.8) |

49.3 (9.6) |

57.9 (14.4) |

55.8 (13.2) |

45.1 (7.3) |

32.8 (0.4) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

15.6 (−9.1) |

6.9 (−13.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −7 (−22) |

−7 (−22) |

4 (−16) |

15 (−9) |

32 (0) |

40 (4) |

50 (10) |

45 (7) |

35 (2) |

25 (−4) |

12 (−11) |

−3 (−19) |

−7 (−22) |

| Averageprecipitationinches (mm) | 3.08 (78) |

2.90 (74) |

4.01 (102) |

3.39 (86) |

3.85 (98) |

3.98 (101) |

4.48 (114) |

4.09 (104) |

4.44 (113) |

3.94 (100) |

3.13 (80) |

3.71 (94) |

45.00 (1,143) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.4 (16) |

7.5 (19) |

2.8 (7.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

2.5 (6.4) |

19.3 (49) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 0.01 in) | 10.1 | 9.3 | 11.0 | 11.2 | 11.9 | 11.3 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 10.3 | 121.3 |

| Average snowy days(≥ 0.1 in) | 2.8 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 9.0 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 63.2 | 61.3 | 59.2 | 58.9 | 66.1 | 68.4 | 69.1 | 71.1 | 71.3 | 69.5 | 66.5 | 65.5 | 65.8 |

| Averagedew point°F (°C) | 19.9 (−6.7) |

21.6 (−5.8) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

37.6 (3.1) |

50.4 (10.2) |

60.1 (15.6) |

64.6 (18.1) |

64.0 (17.8) |

57.6 (14.2) |

45.5 (7.5) |

35.2 (1.8) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

42.6 (5.9) |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 155.4 | 164.0 | 215.0 | 230.7 | 254.5 | 277.3 | 290.1 | 264.4 | 221.8 | 205.5 | 158.5 | 144.5 | 2,581.7 |

| Percentpossible sunshine | 51 | 54 | 58 | 58 | 57 | 62 | 64 | 62 | 59 | 59 | 52 | 49 | 58 |

| Source:NOAA(relative humidity, dew points and sun 1961–1990)[147][154][155] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Baltimore (Maryland Science Center) 1991−2020 normals, extremes 1950–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 77 (25) |

84 (29) |

97 (36) |

98 (37) |

100 (38) |

106 (41) |

108 (42) |

106 (41) |

102 (39) |

95 (35) |

87 (31) |

85 (29) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 65.0 (18.3) |

66.5 (19.2) |

77.0 (25.0) |

87.7 (30.9) |

92.5 (33.6) |

97.3 (36.3) |

99.7 (37.6) |

97.8 (36.6) |

92.9 (33.8) |

85.4 (29.7) |

75.4 (24.1) |

67.1 (19.5) |

100.9 (38.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43.7 (6.5) |

46.8 (8.2) |

55.2 (12.9) |

66.8 (19.3) |

75.9 (24.4) |

85.4 (29.7) |

90.1 (32.3) |

87.3 (30.7) |

80.4 (26.9) |

68.8 (20.4) |

57.6 (14.2) |

48.0 (8.9) |

67.2 (19.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 36.9 (2.7) |

39.4 (4.1) |

46.9 (8.3) |

57.5 (14.2) |

67.0 (19.4) |

76.6 (24.8) |

81.5 (27.5) |

79.1 (26.2) |

72.5 (22.5) |

60.7 (15.9) |

50.1 (10.1) |

41.3 (5.2) |

59.1 (15.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 30.0 (−1.1) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

38.7 (3.7) |

48.2 (9.0) |

58.0 (14.4) |

67.7 (19.8) |

72.9 (22.7) |

71.0 (21.7) |

64.5 (18.1) |

52.6 (11.4) |

42.6 (5.9) |

34.6 (1.4) |

51.1 (10.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 14.7 (−9.6) |

17.3 (−8.2) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

36.2 (2.3) |

46.9 (8.3) |

57.5 (14.2) |

65.6 (18.7) |

63.2 (17.3) |

53.4 (11.9) |

40.3 (4.6) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

22.2 (−5.4) |

12.5 (−10.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −4 (−20) |

−3 (−19) |

12 (−11) |

21 (−6) |

36 (2) |

48 (9) |

58 (14) |

52 (11) |

40 (4) |

30 (−1) |

16 (−9) |

6 (−14) |

−4 (−20) |

| Averageprecipitationinches (mm) | 3.07 (78) |

2.75 (70) |

3.93 (100) |

3.55 (90) |

3.39 (86) |

3.36 (85) |

4.71 (120) |

4.35 (110) |

4.49 (114) |

3.49 (89) |

2.98 (76) |

3.66 (93) |

43.73 (1,111) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 0.01 in) | 9.9 | 9.7 | 10.7 | 11.0 | 11.3 | 10.7 | 10.6 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.1 | 10.2 | 118.7 |

| Source:NOAA[143][147] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Baltimore | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 46.0 (7.8) |

44.4 (6.9) |

45.1 (7.3) |

50.4 (10.2) |

55.9 (13.3) |

68.2 (20.1) |

75.6 (24.2) |

77.4 (25.2) |

73.4 (23.0) |

66.0 (18.9) |

57.2 (14.0) |

50.7 (10.4) |

59.2 (15.1) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[156] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info onPhabricatorand onMediaWiki.org. |

See or editraw graph data.

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1752 | 200 | — |

| 1775 | 5,934 | +2867.0% |

| 1790 | 13,503 | +127.6% |

| 1800 | 26,514 | +96.4% |

| 1810 | 46,555 | +75.6% |

| 1820 | 62,738 | +34.8% |

| 1830 | 80,620 | +28.5% |

| 1840 | 102,313 | +26.9% |

| 1850 | 169,054 | +65.2% |

| 1860 | 212,418 | +25.7% |

| 1870 | 267,354 | +25.9% |

| 1880 | 332,313 | +24.3% |

| 1890 | 434,439 | +30.7% |

| 1900 | 508,957 | +17.2% |

| 1910 | 558,485 | +9.7% |

| 1920 | 733,826 | +31.4% |

| 1930 | 804,874 | +9.7% |

| 1940 | 859,100 | +6.7% |

| 1950 | 949,708 | +10.5% |

| 1960 | 939,024 | −1.1% |

| 1970 | 905,787 | −3.5% |

| 1980 | 786,741 | −13.1% |

| 1990 | 736,016 | −6.4% |

| 2000 | 651,154 | −11.5% |

| 2010 | 620,961 | −4.6% |

| 2020 | 585,708 | −5.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[157] 1790–1960[158]1900–1990[159] 1990–2000[160]2010–2020[15] 1752 estimate & 1775 census[161] | ||

Baltimore reached a peak population of 949,708 at the 1950 U.S. census count. In every ten-year census count since then, the city has lost population, with its 2020 census population at 585,708. In 2011, then-MayorStephanie Rawlings-Blakesaid one of her goals was to increase the city's population, by improving city services to reduce the number of people leaving the city, and by passing legislation protecting immigrants' rights to stimulate growth.[163]Baltimore is identified as asanctuary city.[164]In 2019, then-MayorJack Youngsaid that Baltimore will not assistICEagents with immigration raids.[165]

Baltimore City's population declined from 620,961 in 2010 to 585,708 in 2020, representing a 5.7% drop. In 2020, Baltimore lost more population than any other major city in theUnited States.[166][7][167]

Gentrificationhas increased since the 2000 census, primarily in East Baltimore, downtown, and Central Baltimore, with 14.8% of census tracts having had income growth and home values appreciation at a rate higher than the city overall. Many, but not all, gentrifying neighborhoods are predominantly white areas which have seen a turnover from lower income to higher income households. These areas represent either expansion of existing gentrified areas, or activity around the Inner Harbor, downtown, or the Johns Hopkins Homewood campus.[168]In some neighborhoods in East Baltimore, the Hispanic population has increased, while both the non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black populations have declined.[169]

AfterNew York City,Baltimore was the second city in the United States to reach a population of 100,000.[170][171]From the 1820 to 1850 U.S. censuses, Baltimore was the second most-populous city,[171][172]before being surpassed byPhiladelphiaand the then-independentBrooklynin 1860, and then being surpassed bySt. LouisandChicagoin 1870.[173]Baltimore was among the top 10 cities in population in the United States in every census up to the 1980 census.[174]After World War II, Baltimore had a population approaching 1 million, until the population began to fall after the 1950 census.

Characteristics

[edit]

| Historical racial and ethnic profile | 2020[175] | 2010[176] | 1990[177] | 1970[177] | 1940[177] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 31.9% | 29.6% | 39.1% | 53.0% | 80.6% |

| —Non-Hispanic whites | 27.6% | 28.0% | 38.6% | 52.3%[g] | 80.6% |

| Black or African American(non-Hispanic) | 62.4% | 63.7% | 59.2% | 46.4% | 19.3% |

| Hispanic or Latino(of any race) | 6.0% | 4.2% | 1.0% | 0.9%[g] | 0.1% |

| Asian | 2.8% | 2.3% | 1.1% | 0.3% | 0.1% |

| Race / Ethnicity(NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[178] | Pop 2010[179] | Pop 2020[180] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whitealone (NH) | 201,566 | 174,120 | 157,296 | 30.96% | 28.04% | 26.86% |

| Black or African Americanalone (NH) | 417,009 | 392,938 | 335,615 | 64.04% | 63.28% | 57.30% |

| Native AmericanorAlaska Nativealone (NH) | 1,946 | 1,884 | 1,278 | 0.30% | 0.30% | 0.22% |

| Asianalone (NH) | 9,824 | 14,397 | 21,020 | 1.51% | 2.32% | 3.59% |

| Pacific Islanderalone (NH) | 193 | 192 | 152 | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.03% |

| Some Other Racealone (NH) | 1,143 | 942 | 3,332 | 0.18% | 0.15% | 0.57% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial(NH) | 8,412 | 10,528 | 21,088 | 1.29% | 1.70% | 3.60% |

| Hispanic or Latino(any race) | 11,061 | 25,960 | 45,927 | 1.70% | 4.18% | 7.84% |

| Total | 651,154 | 620,961 | 585,708 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

In the 2010 census[update],Baltimore's population was 63.7%Black,29.6%White(6.9%German,5.8%Italian,4%Irish,2%American,2%Polish,0.5%Greek) 2.3%Asian(0.54%Korean,0.46%Indian,0.37%Chinese,0.36%Filipino,0.21%Nepali,0.16%Pakistani), and 0.4%Native American and Alaska Native.Across races, 4.2% of the population are ofHispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin(1.63%Salvadoran,1.21%Mexican,0.63%Puerto Rican,0.6%Honduran).[15]

As per the 2020 census, 8.1% of residents between 2016 and 2020 were foreign born persons.[175]Females made up 53.4% of the population. The median age was 35 years old, with 22.4% under 18 years old, 65.8% from 18 to 64 years old, and 11.8% 65 or older.[15]

Baltimore has a largeCaribbean Americanpopulation, with the largest groups beingJamaicansandTrinidadians.Baltimore's Jamaican community is largely centered in thePark Heightsneighborhood, but generations of immigrants have also lived in Southeast Baltimore.[181]

In 2005, approximately 30,778 people (6.5%) identified asgay, lesbian, or bisexual.[182]In 2012,same-sex marriage in Marylandwas legalized, going into effect January 1, 2013.[183]

Income and housing

[edit]Between 2016 and 2020, the median household income was $52,164 and the median income per capita was $32,699, compared to the national averages of $64,994 and $35,384, respectively.[175]In 2009, the median household income was $42,241 and the median income per capita was $25,707, compared to the national median income of $53,889 per household and $28,930 per capita.[15]

In 2009, 23.7% of the population lived below the poverty line, compared to 13.5% nationwide.[15]In the 2020 census, 20% of Baltimore residents were living in poverty, compared to 11.6% nationwide.[175]

Housing in Baltimore is relatively inexpensive for large, near-coastal cities of its size. The median sale price for homes in Baltimore as of December 2022 was $209,000, up from $95,000 in 2012.[184][185]Despite the late 2000s housing price collapse, and along with the national trends, Baltimore residents still faced slowly increasing rent, up 3% in the summer of 2010.[186]The median value of owner-occupied housing units between 2016 and 2020 was $242,499.[175]

Thehomelesspopulation in Baltimore is steadily increasing. It exceeded 4,000 people in 2011. The increase in the number of young homeless people was particularly severe.[187]

Life expectancy

[edit]In 2015, life expectancy in Baltimore was 74 to 75 years, compared to the U.S. average of 78 to 80. Fourteen neighborhoods had lower life expectancies thanNorth Korea.The life expectancy in Downtown/Seton Hill was comparable to that ofYemen.[188]

Religion

[edit]

In 2015, 25% of adults in Baltimore reported affiliation with no religion. 50% of the adult population of Baltimore areProtestants.[h]Catholicismis the second-largest religious affiliation, constituting 15% percent of the population, followed byJudaism(3%) andIslam(2%). Around 1% identify with otherChristian denominations.[189][190][191]

Languages

[edit]In 2010, 91% (526,705) of Baltimore residents five years old and older spoke only English at home. Close to 4% (21,661) spoke Spanish. Other languages, such asAfrican languages,French, and Chinese are spoken by less than 1% of the population.[192]

Economy

[edit]Once a predominantly industrial town, with an economic base focused on steel processing, shipping, auto manufacturing (General MotorsBaltimore Assembly), and transportation, Baltimore experienceddeindustrialization,which cost residents tens of thousands of low-skill, high-wage jobs.[193]Baltimore now relies on a low-wageservice economy,which accounts for 31% of jobs in the city.[194][195]Around the turn of the 20th century, Baltimore was the leading U.S. manufacturer ofrye whiskeyandstraw hats.It led in the refining of crude oil, brought to the city by pipeline from Pennsylvania.[196][197][198]

In March 2018, Baltimore's unemployment rate was 5.8%.[199]In 2012, one quarter of Baltimore residents, and 37% of Baltimore children, lived in poverty.[200]The 2012 closure of a major steel plant at Sparrows Point is expected to have a further impact on employment and the local economy.[201]In 2013, 207,000 workers commuted into Baltimore city each day.[202]Downtown Baltimoreis the primary economic asset within Baltimore City and the region, with 29.1 million square feet of office space. The tech sector is rapidly growing as the Baltimore metro ranks 8th in the CBRE Tech Talent Report among 50 U.S. metro areas for high growth rate and number of tech professionals.[203]In 2013,Forbesranked Baltimore fourth among America's "new tech hot spots".[204]

The city is home to theJohns Hopkins Hospital.Other largecompanies in BaltimoreincludeUnder Armour,[205]BRT Laboratories,Cordish Company,[206]Legg Mason,McCormick & Company,T. Rowe Price,andRoyal Farms.[207]Asugar refineryowned byAmerican Sugar Refiningis one of Baltimore's cultural icons. Nonprofits based in Baltimore includeLutheran Services in AmericaandCatholic Relief Services.

Almost a quarter of the jobs in the Baltimore region were in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics as of mid-2013, a fact attributed in part to the city's extensive undergraduate and graduate schools; maintenance and repair experts were included in this count.[208]

Port

[edit]This section needs to beupdated.(March 2024) |

The center of international commerce for the region is theWorld Trade Center Baltimore.It houses the Maryland Port Administration and U.S. headquarters for major shipping lines. Baltimore is ranked 9th for total dollar value of cargo and 13th for cargo tonnage for all U.S. ports. In 2014, total cargo moving through the port totaled 29.5 million tons, down from 30.3 million tons in 2013. The value of cargo traveling through the port in 2014 came to $52.5 billion, down from $52.6 billion in 2013. ThePort of Baltimoregenerates $3 billion in annual wages and salary, as well as supporting 14,630 direct jobs and 108,000 jobs connected to port work. In 2014, the port generated more than $300 million in taxes.[209]

The port serves over 50 ocean carriers, making nearly 1,800 annual visits. Among all U.S. ports, Baltimore is first in handling automobiles, light trucks, farm and construction machinery; and imported forest products, aluminum, and sugar. The port is second in coal exports. The Port of Baltimore's cruise industry, which offers year-round trips on several lines, supports over 500 jobs and brings in over $90 million to Maryland's economy annually. Growth at the port continues with the Maryland Port Administration plans to turn the southern tip of the former steel mill into a marine terminal, primarily for car and truck shipments, and for anticipated new business coming to Baltimore after the completion of thePanama Canal expansion project.[209]

Tourism

[edit]Baltimore's history and attractions have made it a popular tourist destination. In 2014, the city hosted 24.5 million visitors, who spent $5.2 billion.[210]The Baltimore Visitor Center, which is operated byVisit Baltimore,is located on Light Street in the Inner Harbor. Much of the city's tourism centers around the Inner Harbor, with theNational Aquariumbeing Maryland's top tourist destination. Baltimore Harbor's restoration has made it "a city of boats", with several historic ships and other attractions on display and open to the public. TheUSSConstellation,the last Civil War-era vessel afloat, is docked at the head of the Inner Harbor; theUSSTorsk,a submarine that holds the Navy's record for dives (more than 10,000); and the Coast Guard cutterWHEC-37,the last surviving U.S. warship that was inPearl Harborduring theJapanese attackon December 7, 1941, and which engaged Japanese Zero aircraft during the battle.[211]

Also docked is thelightshipChesapeake,which for decades marked the entrance to Chesapeake Bay; and the Seven Foot Knoll Lighthouse, the oldest survivingscrew-pile lighthouseon Chesapeake Bay, which once marked the mouth of the Patapsco River and the entrance to Baltimore. All of these attractions are owned and maintained by theHistoric Ships in Baltimoreorganization. The Inner Harbor is also the home port ofPride of Baltimore II,the state of Maryland's "goodwill ambassador" ship, a reconstruction of a famousBaltimore Clippership.[211]

Other tourist destinations include sporting venues such asOriole Park at Camden Yards,M&T Bank Stadium,andPimlico Race Course,Fort McHenry,theMount Vernon,Federal Hill,andFells Pointneighborhoods,Lexington Market,Horseshoe Casino,and museums such as theWalters Art Museum,theBaltimore Museum of Industry,theBabe Ruth Birthplace and Museum,theMaryland Science Center,and theB&O Railroad Museum.

-

The Baltimore Visitor Center at theInner Harbor

-

Fountain near visitor center in Inner Harbor

-

Sunset views from Inner Harbor

-

Baltimore is the home of theNational Aquarium,one of the world's largest aquariums.

Culture

[edit]

Baltimore has historically been a working-class port town, sometimes dubbed a "city of neighborhoods". It comprises 72 designated historic districts[212]traditionally occupied by distinct ethnic groups. Most notable today are three downtown areas along the port: the Inner Harbor, frequented by tourists because of its hotels, shops, and museums; Fells Point, once a favorite entertainment spot for sailors but now refurbished and gentrified (and featured in the movieSleepless in Seattle); andLittle Italy,located between the other two, where Baltimore's Italian-American community is based – and where U.S. House SpeakerNancy Pelosigrew up.

Further inland,Mount Vernonis the traditional center of cultural and artistic life of the city. It is home to a distinctiveWashington Monument,set atop a hill in a 19th-century urban square, that predates the monument in Washington, D.C. by several decades. Baltimore has a significantGerman Americanpopulation,[213]and was the second-largest port of immigration to the United States behindEllis Islandin New York and New Jersey. Between 1820 and 1989, almost 2 million who were German,Polish,English, Irish,Russian,Lithuanian,French,Ukrainian,Czech,GreekandItaliancame to Baltimore, mostly between 1861 and 1930. By 1913, when Baltimore was averaging forty thousand immigrants per year, World War I closed off the flow of immigrants. By 1970, Baltimore's heyday as an immigration center was a distant memory. There was aChinatowndating back to at least the 1880s, which consisted of 400 Chinese residents. A local Chinese-American association remains based there, with one Chinese restaurant as of 2009.

Beer making thrived in Baltimore from the 1800s to the 1950s, with over 100 old breweries in the city's past.[214]The best remaining example of that history is the oldAmerican Brewery Buildingon North Gay Street and theNational Brewing Companybuilding in theBrewer's Hillneighborhood. In the 1940s the National Brewing Company introduced the nation's first six-pack. National's two most prominent brands, wereNational BohemianBeer colloquially "Natty Boh" andColt 45.Listed on thePabstwebsite as a "Fun Fact", Colt 45 was named after running back#45 Jerry Hillof the 1963Baltimore Coltsand not the.45 caliber handgun ammunition round.Both brands are still made today, albeit outside of Maryland, and served all around the Baltimore area at bars, as well asOriolesandRavensgames.[215]The Natty Boh logo appears on all cans, bottles, and packaging. Merchandise featuring him can be found in shops in Maryland, including several inFells Point.

Each year theArtscapetakes place in the city in theBolton Hillneighborhood, close to the Maryland Institute College of Art. Artscape styles itself as the "largest free arts festival in America".[citation needed]Each May, theMaryland Film Festivaltakes place in Baltimore, using all five screens of the historicCharles Theatreas its anchor venue. Many movies and television shows have been filmed in Baltimore.Homicide: Life on the Streetwas set and filmed in Baltimore, as well asThe Wire.House of CardsandVeepare set in Washington, D.C. but filmed in Baltimore.[216]

Baltimore has cultural museums in many areas of study.The Baltimore Museum of Artand theWalters Art Museumare internationally renowned for their collections of art. The Baltimore Museum of Art has the largest holding of works byHenri Matissein the world.[217]TheAmerican Visionary Art Museumhas been designated byCongressas America's national museum forvisionary art.[218]TheNational Great Blacks In Wax Museumis the first African American wax museum in the country, featuring more than 150 life-size and lifelike wax figures.[51]

Cuisine

[edit]Baltimore is known for its Marylandblue crabs,crab cake,Old Bay Seasoning,pit beef, and the "chicken box". The city has many restaurants in or around the Inner Harbor. The most known and acclaimed are the Charleston, Woodberry Kitchen, and theCharm City Cakesbakery featured on the Food Network'sAce of Cakes.TheLittle Italyneighborhood's biggest draw is the food. Fells Point also is a foodie neighborhood for tourists and locals and is where the oldest continuously running tavern in the country, "The Horse You Came in on Saloon", is located.[219]

Many of Baltimore's upscale restaurants are found in Harbor East. Five public markets are located across Baltimore. TheBaltimore Public Market Systemis the oldest continuously operating public market system in the United States.[220]Lexington Marketis one of the longest-running markets in the world and the longest running in the country, having been around since 1782. The market continues to stand at its original site. Baltimore is the last place in America where one can still findarabbers,vendors who sell fresh fruits and vegetables from a horse-drawn cart that goes up and down neighborhood streets.[221]Food- and drink-rating siteZagatranked Baltimore second in a list of the 17 best food cities in the US in 2015.[222]

Local dialect

[edit]Baltimore city, along with its surrounding regions, is home to a unique local dialect known as theBaltimore dialect.It is part of the largerMid-Atlantic American Englishgroup and is noted to be very similar to thePhiladelphia dialect.[223][224]

The so-called "Bawlmerese" accent is known for its characteristic pronunciation of its long "o" vowel, in which an "eh" sound is added before the long "o" sound (/oʊ/ shifts to [ɘʊ], or even [eʊ]).[225]It adopts Philadelphia's pattern of the short "a" sound, such that the tensed vowel in words like "bath" or "ask" does not match the more relaxed one in "sad" or "act".[223]

Baltimore nativeJohn Watersparodies the city and its dialect extensively in his films. Most arefilmed in Baltimore,including the 1972 cult classicPink Flamingos,as well asHairsprayand itsBroadway musical remake.

Performing arts

[edit]

Baltimore has four state-designated arts and entertainment districts: The Pennsylvania Avenue Black Arts and Entertainment District,Station North Arts and Entertainment District,Highlandtown Arts District,and the Bromo Arts & Entertainment District.[226][227][228]

The Baltimore Office of Promotion and The Arts, a non-profit organization, produces events and arts programs as well as managing several facilities. It is the official Baltimore City Arts Council. BOPA coordinates Baltimore's major events, including New Year's Eve and July 4 celebrations at the Inner Harbor,Artscape,which is America's largest free arts festival, Baltimore Book Festival, Baltimore Farmers' Market & Bazaar, School 33 Art Center's Open Studio Tour, and the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Parade.[229]

TheBaltimore Symphony Orchestrais an internationally renowned orchestra, founded in 1916 as a publicly funded municipal organization. Its most recent music director wasMarin Alsop,a protégé ofLeonard Bernstein's.Centerstageis the premier theater company in the city and a regionally well-respected group. TheLyric Opera Houseis the home ofLyric Opera Baltimore,which operates there as part of the Patricia and Arthur Modell Performing Arts Center. Shriver Hall Concert Series, founded in 1966, presents classical chamber music and recitals featuring nationally and internationally recognized artists.[230]

The Baltimore Consorthas been a leading early music ensemble for over twenty-five years. The France-Merrick Performing Arts Center, home of the restoredThomas W. Lamb-designedHippodrome Theatre,has afforded Baltimore the opportunity to become a major regional player in the area of touring Broadway and other performing arts presentations. Renovating Baltimore's historic theatres has become widespread throughout the city. Renovated theatres include theEveryman,Centre,Senator,and most recentlyParkwayTheatre. Other buildings have been reused. These include the formerMercantile Deposit and TrustCompany bank building, which is nowThe Chesapeake Shakespeare CompanyTheater.

Baltimore has a wide array of professional (non-touring) and community theater groups. Aside from Center Stage, resident troupes in the city include The Vagabond Players, the oldest continuously operating community theater group in the country,Everyman Theatre,Single Carrot Theatre,and Baltimore Theatre Festival. Community theaters in the city include Fells Point Community Theatre and theArena Players Inc.,which is the nation's oldest continuously operating African American community theater.[231]In 2009, theBaltimore Rock Opera Society,an all-volunteer theatrical company, launched its first production.[232]

Baltimore is home to thePride of Baltimore Chorus,a three-time international silver medalist women's chorus, affiliated withSweet Adelines International.TheMaryland State Boychoiris located in the northeastern Baltimore neighborhood of Mayfield.

Baltimore is the home of non-profitchamber musicorganization Vivre Musicale. VM won a 2011–2012 award for Adventurous Programming from theAmerican Society of Composers, Authors and PublishersandChamber Music America.[233]

ThePeabody Institute,located in the Mount Vernon neighborhood, is the oldest conservatory of music in the United States.[234]Established in 1857, it is one of the most prestigious in the world,[234]along withJuilliard,Eastman,and theCurtis Institute.TheMorgan State UniversityChoir is also one of the nation's most prestigious university choral ensembles.[235]The city is home to theBaltimore School for the Arts,a public high school in the Mount Vernon neighborhood of Baltimore. The institution is nationally recognized for its success in preparation for students entering music (vocal/instrumental), theatre (acting/theater production), dance, and visual arts.

In 1981, Baltimore hosted the first International Theater Festival, the first such festival in the country. Executive producer Al Kraizer staged 66 performances of nine shows by internationaltheatre companies,including from Ireland, the United Kingdom, South Africa and Israel.[236]The festival proved to be expensive to mount, and in 1982 the festival was hosted in Denver, called the World Theatre Festival,[237]at theDenver Center for Performing Arts,after the city had asked Kraizer to organize it.[238]

In June 1986, the 20th Theatre of Nations, sponsored by theInternational Theatre Institute,was held in Baltimore, the first time it had been held in the U.S.[239]

Sports

[edit]Baseball

[edit]

Baltimore has a long and storied baseball history, including its distinction as the birthplace ofBabe Ruthin 1895. The original19th century Baltimore Orioleswere one of the most successful early franchises, featuring numerous hall of famers during its years from 1882 to 1899. As one of the eight inaugural American League franchises, the Baltimore Orioles played in the AL during the 1901 and 1902 seasons. The team moved to New York City before the 1903 season and was renamed the New York Highlanders, which later became theNew York Yankees. Ruth played for theminor league Baltimore Oriolesteam, which was active from 1903 to 1914. After playing one season in 1915 as the Richmond Climbers, the team returned the following year to Baltimore, where it played as the Orioles until 1953.[citation needed]

The team currently known as theBaltimore Orioleshas represented Major League Baseball locally since 1954 when theSt. Louis Brownsmoved to Baltimore. The Orioles advanced to the World Series in 1966, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1979 and 1983, winning three times (1966, 1970 and 1983), while making the playoffs all but one year (1972) from 1969 through 1974.[240]

In 1995, local player (and later Hall of Famer)Cal Ripken Jr.brokeLou Gehrig's streak of 2,130 consecutive games played, for which Ripken was namedSportsman of the YearbySports Illustratedmagazine.[citation needed]Six former Orioles players, including Ripken (2007), and two of the team's managers have been inducted into theBaseball Hall of Fame.

Since 1992, the Orioles' home ballpark has beenOriole Park at Camden Yards,which has been hailed as one of the league's best since it opened.[241]

Football

[edit]

Prior to aNational Football Leagueteam moving to Baltimore, there had been several attempts at a professional football team prior to the 1950s, which were blocked by the Washington team and its NFL friends. Most were minor league orsemi-professionalteams. The first major league to base a team in Baltimore was theAll-America Football Conference(AAFC), which had a team named theBaltimore Colts.The AAFC Colts played for three seasons in the AAFC (1947, 1948, and 1949), and when the AAFC folded following the 1949 season, moved to the NFL for a single year (1950) before going bankrupt.

In 1953, the NFL'sDallas Texansfolded. Its assets and player contracts were purchased by an ownership team headed by Baltimore businessmanCarroll Rosenbloom,who moved the team to Baltimore, establishing a new team also named theBaltimore Colts.During the 1950s and 1960s, the Colts were one of the NFLs more successful franchises, led byPro Football Hall of FamequarterbackJohnny Unitaswho set a then-record of 47 consecutive games with a touchdown pass. The Colts advanced to theNFL Championshiptwice (1958 & 1959) andSuper Bowltwice (1969 & 1971), winning all exceptSuper Bowl IIIin 1969. After the 1983 season, the teamleft Baltimore for Indianapolis in 1984,where they became theIndianapolis Colts.

The NFL returned to Baltimore when the formerCleveland Brownsmoved to Baltimore to become theBaltimore Ravensin 1996. Since then, the Ravens won a Super Bowl championship in2000and2012,sevenAFC Northdivision championships (2003, 2006, 2011, 2012, 2018, 2019 and 2023), and appeared in fiveAFC Championship Games(2000, 2008, 2011, 2012 and 2023).[242]

Baltimore also hosted aCanadian Football Leaguefranchise, theBaltimore Stallionsfor the1994and1995 seasons.Following the 1995 season, and ultimate end to theCanadian Football League in the United Statesexperiment, the team was sold and relocated toMontreal.

Other teams and events

[edit]

The first professional sports organization in the United States,The Maryland Jockey Club,was formed in Baltimore in 1743.Preakness Stakes,the second race in theUnited States Triple Crown of Thoroughbred Racing,has been held every May atPimlico Race Coursein Baltimore since 1873.

Collegelacrosseis a common sport in the spring, as theJohns Hopkins Blue Jaysmen's lacrosse team has won 44 national championships, the most of any program in history. In addition,Loyola Universitywon its first men'sNCAAlacrosse championship in 2012.

TheBaltimore Blastare a professional arenasoccerteam that play in theMajor Arena Soccer Leagueat theSECU Arenaon the campus ofTowson University.The Blast have won nine championships in various leagues, including the MASL. A previous entity of theBlastplayed in theMajor Indoor Soccer Leaguefrom 1980 to 1992, winning one championship. The Baltimore Kings, a Baltimore Blast affiliate,[243]joinedMASL 3in 2021 to begin play in 2022.[244]

FC Baltimore 1729was a semi-professional soccer club in theNPSL league,with the goal of bringing a community-oriented competitive soccer experience to Baltimore. Their inaugural season started on May 11, 2018, and they played their home games atCCBC Essex Field.Baltimore City F.C. is anEastern Premier Soccer Leagueclub that plays since 2023 at Middle Branch Fitness Center inCherry Hill.

TheBaltimore Blueswere a semi-professionalrugby leagueclub which began competition in theUSA Rugby Leaguein 2012.[245]TheBaltimore Bohemianswere an Americansoccer clubwhich competed in theUSL Premier Development League,the fourth tier of theAmerican Soccer Pyramid.Their inaugural season started in the spring of 2012.

TheBaltimore Grand Prixdebuted along the streets of the Inner Harbor section of the city's downtown on September 2–4, 2011. The event played host to theAmerican Le Mans Serieson Saturday and theIndyCar Serieson Sunday. Support races from smaller series were also held, includingIndy Lights.After three consecutive years, on September 13, 2013, it was announced that the event would not be held in 2014 or 2015 due to scheduling conflicts.[246]

The athletic equipment companyUnder Armouris also based in Baltimore. Founded in 1996 byKevin Plank,aUniversity of Marylandalumnus, the company's headquarters are located in Tide Point, adjacent toFort McHenryand theDomino Sugarfactory. TheBaltimore Marathonis the flagship race of several races. The marathon begins atCamden Yardsand travels through many diverse neighborhoods of Baltimore, including the scenic Inner Harbor waterfront area, historic Federal Hill,Fells Point,andCanton, Baltimore.The race then proceeds to other important focal points of the city such asPatterson Park,Clifton Park, Lake Montebello, the Charles Village neighborhood, and the western edge of downtown. After winding through 42.195 kilometres (26.219 mi) of Baltimore, the race ends at virtually the same point at which it starts.

TheBaltimore Brigadewere anArena Football Leagueteam based in Baltimore that, from 2017 to 2019, played atRoyal Farms Arena.In 2019, the team ceased operations along with the rest of the league.

Parks and recreation

[edit]

Baltimore has over 4,900 acres (1,983 ha) of parkland.[247]The Baltimore City Department of Recreation and Parks manages the majority of parks and recreational facilities in the city, includingPatterson Park,Federal Hill Park,andDruid Hill Park.[248]The city is home toFort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine,a coastal star-shaped fort best known for its role in the War of 1812. As of 2015[update],The Trust for Public Land,a national land conservation organization, ranks Baltimore 40th among the 75-largest U.S. cities.[247]

Law, government, and politics

[edit]Baltimore is anindependent city,and not part of anycounty.For most governmental purposes under Maryland law, Baltimore City is treated as a county-level entity. TheUnited States Census Bureauuses counties as the basic unit for presentation of statistical information in the United States, and treats Baltimore as a county equivalent for those purposes.

Baltimore has been aDemocraticstronghold for over 150 years, with Democrats dominating every level of government. In virtually all elections, the Democratic primary is the real contest.[249]As of the 2020 elections, registered Democrats outnumbered registeredRepublicansby almost 10-to-1.[250]No Republican has been elected to the City Council since 1939. The city's last Republican mayor,Theodore McKeldin,left office in 1967. No Republican candidate since then has received 25 percent or more of the vote. In the2016and2020 mayoral elections,the Republicans were pushed into third place by write-in and independent candidates, respectively. The last Republican candidate for president to win the city wasDwight Eisenhowerin his successful reelection bid in 1956.

The city hosted the first sixDemocratic National Conventions,from 1832 through 1852, and hosted the DNC again in1860,1872,and1912.[251]

Voter registration

[edit]| Voter registration and party enrollment as of March 2024[252] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | 296,108 | 75.12% | |||

| Unaffiliated | 62,566 | 15.87% | |||

| Republican | 28,400 | 7.2% | |||

| Libertarian | 1,192 | 0.3% | |||

| Other parties | 5,931 | 1.5% | |||

| Total | 394,197 | 100% | |||

City government

[edit]Mayor

[edit]Brandon Scottis the currentmayor of Baltimore.He was elected in 2020 and took office on December 8, 2020.

Scott succeededJack Young,who took office on May 2, 2019. Young had been the president of theBaltimore City Councilwhen MayorCatherine Pughwas accused of aself-dealingbook-sales arrangement. He became acting mayor on April 2 when she took a leave of absence, then mayor upon her resignation.[253][254]

Pugh, a Democrat, won the2016 mayoral electionwith 57.1% of the vote and took office on December 6, 2016.[255]

Stephanie Rawlings-Blakeassumed the office of Mayor on February 4, 2010, when predecessor Dixon's resignation became effective.[256]Rawlings-Blake had been serving as City Council President at the time. She was elected to a full term in 2011, defeating Pugh in the primary election and receiving 84% of the vote.[257]

Sheila Dixonbecame the first female mayor of Baltimore on January 17, 2007. As the former City Council President, she assumed the office of Mayor when former MayorMartin O'Malleytook office as Governor of Maryland.[258]On November 6, 2007, Dixon won theBaltimore mayoral election.Mayor Dixon's administration ended less than three years after her election, the result of a criminal investigation that began in 2006 while she was still City Council President. She was convicted on a single misdemeanor charge ofembezzlementon December 1, 2009. A month later, Dixon made anAlford pleato aperjurycharge and agreed to resign from office; Maryland, like most states, does not allow convicted felons to hold office.[259][260]

Baltimore City Council

[edit]Grassroots pressure for reform, voiced asQuestion P,restructured the city council in November 2002, against the will of the mayor, the council president, and the majority of the council. A coalition of union and community groups, organized by theAssociation of Community Organizations for Reform Now(ACORN), backed the effort.[261]

Baltimore City Councilis made up of 14 single-member districts and one elected at-large council president.[262][263]

Law enforcement

[edit]

TheBaltimore City Police Departmentis the current primary law enforcement agency serving Baltimore citizens. It was founded 1784 as a "Night City Watch" and day Constables system and later reorganized as a City Department in 1853, with a later reorganization under State of Maryland supervision in 1859, with appointments made by theGovernor of Marylandafter a period of civic and elections violence with riots in the later part of the decade. Campus and building security for the city'spublic schoolsis provided by the Baltimore City Public Schools Police, established in the 1970s.