Dizi(instrument)

| |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 421.121.12 (Open side-blown flutes with fingerholes) |

| Related instruments | |

| |

| Sound sample | |

Thedizi(Chinese:Địch tử;pinyin:dízi,pronounced[tǐt͡sɨ]), is a Chinesetransverse flute.It is also sometimes known as thedi(Địch) orhéngdi(Hoành địch), and has varieties includingQudi(Khúc địch),Bangdi(Bang địch), andXindi(Tân địch). It is a majorChinese musical instrumentthat is widely used in many genres ofChinese folk music,Chinese opera,as well as the modernChinese orchestra.Thediziis also a popular instrument among the Chinese people as it is simple to make and easy to carry.[a]

Mostdiziare made ofbamboo,which explains whydiziare sometimes known by simple names such asChinesebamboo flute.However, "bamboo" is perhaps more of a Chinese instrument classification like "woodwind"in the West. Northern Chinesediziare made from purple or violet bamboo, whiledizimade inSuzhouandHangzhouare made from white bamboo.Diziproduced in southern Chinese regions such asChaozhouare often made of very slender, lightweight, light-colored bamboo and are much quieter in tone.

Although bamboo is the common material for thedizi,it is also possible to finddizimade from otherkinds of wood,or even fromstone.Jadedizi(orNgọc địch;yùdi) are popular among bothcollectorsinterested in their beauty, and among professional players who seek an instrument with looks to match the quality of their renditions; however, jade may not be the best material fordizisince, as with metal, jade may not be as tonally responsive as bamboo, which is more resonant.[dubious–discuss][1]

Thediziis not the only bamboo flute ofChina.Other Chinese bamboo wind instruments include the vertical end-blownxiaoand thekoudi.

History

[edit]Recently, archaeologists have discovered evidence suggesting that the simple transverse flutes (though without the distinctivemokongof thedizi) have been present in China for over 9,000 years. Fragments of bone flutes from this period are still playable today, and are remarkably similar to modern versions in terms of hole placement, etc. TheJiahuneolithic site in central Henan province of China has yielded flutes dating back to 7,000 BC – 5,000 BC that could represent the earliest playable instruments ever found.[2]These flutes were carved with five to eight holes, and are capable of producing sounds that roughly span an octave.[3]Thedizias we know it today roughly dates to the 5th century BC,[4]and there have been examples of bamboodizithat date back to 2nd century BC.[5]

These flutes share common features with othersimple flutesfrom cultures all around the world. Multiple examples from different cultures consist of a drilled piece of bone, which is well-suited as a material due to its hollow nature. The earliest known examples of bone flutes date back around 42,000 years ago.[6]

Modern modifications

[edit]

Traditionallydiziis made by using a single piece of bamboo. While simple and straightforward, it is also impossible to change the fundamental tuning once the bamboo is cut, which made it a problem when it was played with other instruments in a modernChinese orchestra.In the 1920s musician Zheng Jinwen (Trịnh cận văn,1872–1935) resolved this issue by inserting a copper joint to connect two pieces of shorter bamboo. This method allows the length of the bamboo to be modified for minute adjustment to its fundamental pitch.[7][8]

On traditionaldizithe finger-holes are spaced approximately equidistant, which produces a temperament of mixed whole-tone and three-quarter-tone intervals. Zheng also repositioned the figure-holes to change the notes produced.[7]During the middle of the 20th centurydizimakers further changed the finger hole placements to allow for playing inequal temperament,as demanded by new musical developments and compositions, although the traditionaldizicontinue to be used for purposes such askunquaccompaniment.

In the 1930s, an 11-hole, fullychromaticversion of thediziwas created called thexindi(Tân địch), pitched in the same range as the western flute. However, the modified dizi's extra tone holes prevent the effective use of the membrane, so this instrument lacks the inherent timbre of the traditionaldizifamily.[citation needed]

While thebangdi(pitched in the same range as western piccolo) andqudi(pitched a fourth or fifth lower than thebangdi) are the most prevalent, otherdiziinclude thexiaodi/gaoyindi(pitched a fourth of fifth higher than thebangdi), thedadi/diyindi(pitched a fourth or fifth lower thanqudi), and thedeidi/diyindadi(pitched an octave lower thanqudi.)[citation needed]

Membrane

[edit]

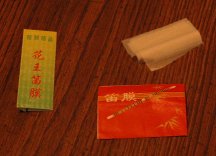

Whereas most simple flutes have only a blowing hole (known aschui kong(Xuy khổng) in Chinese) and finger-holes, thedizihas a very different additional hole, called amo kong(Mô khổng), between the embouchure and finger-holes. A special membrane calleddimo(Địch mô,lit. "dimembrane "), made from an almost tissue-like shaving of reed (made from the inner skin of bamboo cells), is made taut and glued over this hole, traditionally with a substance calledejiao,ananimal glue.Garlic juice may also be used to adhere thedimo,but it is not recommended as a permanent replacement. This application process, in which fine wrinkles are created in the centre of thedimoto create a penetrating buzzytimbre,is an art form in itself.

Thedimo-coveredmo konghas a distinctiveresonatingeffect on the sound produced by thedizi,making it brighter and louder, and addingharmonicsto give the final tone a buzzing, nasal quality.Dizihave a relatively large range, covering about two-and-a-quarteroctaves.

Playing styles and techniques

[edit]

Contemporary 'dizi' styles or schools based on the professional conservatory repertory are divided into two:Northern and Southern,each style having different preferences indiziand playing techniques, with different methods for embellishment andornamentationof the melody.[9]

- Northern school (Beipai) – Thediziused for the Northern school, thebangdi,is shorter and higher in pitch, and its sound quality is brighter and more shrill. In Northern China, it is used inkunquandbangziopera, and as well as regional musical genres such aserrentai.Dizimusic of the Northern school is characterized by a fast, rhythmic andvirtuosicplaying, employing techniques such asglissando,tremolo,flutter tonguing, and fast tonguing.

- Southern school (Nanpai) – In Southern China, the qudi is the lead melodic instrument ofkunquopera and is also used in music such asJiangnan sizhu.It is longer, and has a more mellow, lyrical tone. The music of the Southern school is usually slower, and the ornamentations are predominantly short melodic turns, trills, andappoggiaturaorgrace note.

Diziare often played using various "advanced" techniques, such ascircular breathing,slides, popped notes, harmonics, "flying finger" trills, multiphonics,fluttertonguing,anddouble-tonguing,which are also common in similar instruments, such as thewestern concert fluteandrecorder.Most professional players have a set of sevendizi,each in a different key (and size). Additionally, master players and those seeking distinctive sounds such as birdsong may use extremely small or very largedizi.

Performers

[edit]

There have been several major performers of the 20th century who have contributed todiziplaying in the new conservatory professional concert repertory, often based on or adapted from regional folk styles. Following theChinese Communist Revolution,and according to theYan'an forumtalks, the instrument was appreciated for its popular roots, and used extensively inrevolutionary music.[10][11]

Feng Zicun(Phùng tử tồn,1904–1987) was born in Yangyuan,Hebeiprovince. Of humble origins, Feng had established himself as a folk musician by the time of the founding of thePeople’s Republic of China,playing thedizias well as the four-string fiddlesihuin local song and dance groups, folksongs and stilt dances. He also introducedErrentai,the local opera ofInner Mongolia,to Hebei after spending four years there as a musician in the 1920s.

In 1953, Feng was appointed to the state-supported Central Song and Dance Ensemble inBeijingasdizisoloist, and accepted a teaching post at theChina Conservatory of Music(Beijing) in 1964.

Feng adapted traditional folk ensemble pieces into dizi solos, such asXi xiang feng(Happy Reunion),Wu bangzi(Five Clappers), contributing to the new Chinese conservatory curricula in traditional instrument performance. Feng’s style, virtuosic and lively, has been known as representative of the folk musical traditions of northern China.

Liu Guanyue(Lưu quản nhạc,1918–1990) was born inAn'guo county,Hebei. Born to a poor peasant family, Liu was a professional folk musician who had earned a meagre living playing theguanzi,suona,anddiziin rural ritual ensembles before becoming a soloist in the Tianjin Song-and-Dance Ensemble(Tianjin gewutuan)in 1952.

Liu together with Feng Zicun are said to be representatives of the Northerndizistyle. His pieces, includingYin zhong niao(Birds in the Shade),He ping ge(Doves of Peace) andGu xiang(Old Home village) have become part of the new conservatory professional concert repertory.

Lu Chunling(Lục xuân linh,1921–2018) was born inShanghai.In pre-1949 Shanghai, Lu worked atrishawdriver, but was also an amateur musician, performing the Jiangnan sizhu folk ensemble repertory. In 1952, Lu becamedizisoloist with the Shanghai Folk Ensemble(Shanghai minzu yuetuan),and also at the Shanghai Opera Company(Shanghai geju yuan)from 1971 to 1976. In 1957 he taught at theShanghai Conservatory of Music,and became associate professor in 1978.

Lu has performed in many countries as well as throughout China and has made many recordings. Hisdiziplaying style has become representative of theJiangnandizitradition in general. He is well known as a longtime member of the famousJiangnan sizhumusic performance quartet consisting of Lu Chunling, Zhou Hao, Zhou Hui, and Ma Shenglong. His compositions includeJinxi(Today and Yesterday).

Zhao Songting(Triệu tùng đình,1924–2001) was born inDongyangcounty,Zhejiang.Zhao trained as a teacher in Zhejiang, and studied law and Chinese and Western music in Shanghai. In the 1940s he worked as a music teacher in Zhejiang, and became thedizisoloist in theZhejiang Song and Dance Ensemble(Zhejiang Sheng Gewutuan) in 1956. He also taught at theShanghai Conservatory of Musicand theZhejiang College of Arts(Zhejiang Sheng Yishu Xuexiao).

Because of his middle-class background, Zhao suffered in the political campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s and was not allowed to perform, instead he taught many students who went on to become leading professionaldiziplayers, and to refinedizidesign. He was reinstated in his former positions in 1976.

Zhao's compositions includeSan Wu Qi(Three-Five-Seven), which is based on a melody fromWuju(Zhejiang traditional opera).

Yu Xunfa(Du tốn phát,1946–2006) was a prominentdizisoloist and composer from Shanghai. He performed with theShanghai National Orchestraand served as Head of the Chinese Dizi Culture Research Centre of Shanghai. TheState Council of the People's Republic of Chinagave him a Life Achievement Award as well as a Lifelong Special Allowance from the State. He is also known for having invented thekoudiin 1971.

Ma Di( mã địch ) is a current composer and soloist known for his technique on the instrument.

Tang Junqiao( đường tuấn kiều ) is a practitioner with international performances alongsideShanghai Symphony Orchestra,New York Philharmonic,andLondon Symphony Orchestra,as well as in movieCrouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.[12]

Use in other music genres

[edit]Ron Korb(Long địch ( âm nhạc gia )or phonetically translated to "Lôi ân khấu bá"), born in Toronto, Canada, is the first renowned western musician playingdizialong with numerous other world woodwinds. He graduated from the Faculty of Music at the University of Toronto with an honors degree in performance. On many of his recordings, he uses thedizias the lead instrument. He has also useddiziin the film soundtracks ofThe White Countess,Relic Hunter,China Rises,andLong Life, Happiness, & Prosperity.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Malcolm Tattersall (Feb 2007)."Does It Matter What It's Made Of?".RetrievedSeptember 7,2018.

- ^Brookhaven National Laboratory (September 22, 1999)."Brookhaven Lab Expert Helps Date Flute Thought to be Oldest Playable Musical Instrument".Archived fromthe originalon January 14, 2016.(also published atScienceDaily ( "Brookhaven Lab Expert Helps Date Flute Thought To Be Oldest Playable Musical Instrument" )

- ^Tedesco, Laura Anne (October 2000)."Jiahu (ca. 7000–5700 B.C.)".Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^"di (musical instrunment)".Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^Howard L. Goodman (2010).Xun Xu and the politics of precision in third-century AD China.Brill Publishers.p. 226.ISBN978-90-04-18337-7.

- ^Chukov (Eds.), T. V. Petkova & V. S. (2018).2nd International e-Conference on Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences: Conference Proceedings.Center for Open Access in Science, Belgrade.doi:10.32591/coas.e-conf.02.01001f.ISBN978-86-81294-01-7.S2CID192322971.

- ^abFrederick Lau (2008). Kai-wing Chow (ed.).Beyond the May Fourth Paradigm: In Search of Chinese Modernity.Lexington Books. pp. 212–215.ISBN978-0739111222.

- ^Trần chính sinh(22 October 2001).Đàm đàm dân tộc quản nhạc khí thính giác huấn luyện tại diễn tấu trung đích tác dụng(in Chinese).

- ^Frederick Lau (2008).Music in China.Oxford University Press. pp. 43–45.ISBN978-0-19-530124-3.

- ^"China's Communist Party has co-opted ancient music".The Economist.2 September 2023.ISSN0013-0613.Retrieved2023-09-02.

The party has a history of co-opting music for its own causes. Under Mao Zedong ostensibly old folk songs were rewritten with revolutionary lyrics and sometimes composed from scratch, says Kai Tang of the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna. The solo repertory associated with the dizi, a traditional form of flute, was composed almost entirely after 1949 and, in the early days, made up mostly of revolutionary music.

- ^Lau, Frederick (1995)."Individuality and Political Discourse in Solo" Dizi "Compositions".Asian Music.Vol. 27, no. 1. pp. 133–152.doi:10.2307/834499.ISSN0044-9202.

- ^Chen, Nan (6 October 2017)."Worthy envoy for the flute".China Daily.Retrieved19 November2017.

- New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians,second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London, 2001).

External links

[edit]![]() Media related toDiziat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toDiziat Wikimedia Commons