Battle of the Nile

| Battle of the Nile | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of theFrench campaign in Egypt,theMediterranean campaignandother naval operations | |||||||

The Destruction ofL'Orientat the Battle of the Nile George Arnald,1827,National Maritime Museum,inGreenwich,London,England | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

14 ships of the line 1 sloop (OOB) |

13 ships of the line 4 frigates (OOB) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

218 killed 677 wounded |

2,000–8,000 killed, wounded or captured[Note A] 2 ships of the line destroyed 9 ships of the line captured 2 frigates destroyed | ||||||

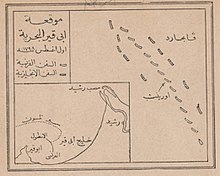

Location within Lower Egypt | |||||||

TheBattle of the Nile(also known as theBattle of Aboukir Bay;French:Bataille d'Aboukir) was a major naval battle fought between the BritishRoyal Navyand the Navy of theFrench RepublicatAboukir Bayon the Mediterranean coast off theNile DeltaofEgyptbetween 1–3 August 1798. The battle was the climax of anaval campaignthat had raged across the Mediterranean during the previous three months, as a large French convoy sailed fromToulontoAlexandriacarrying an expeditionary force under GeneralNapoleon Bonaparte.The British fleet was led in the battle by Rear-Admiral SirHoratio Nelson;they decisively defeated the French under Vice-AdmiralFrançois-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers,destroying the best of the French navy, which was weakened for the rest of theNapoleonic Wars.

Bonaparte sought to invade Egypt as the first step in a campaign againstBritish India,as part of a greater effort to drive Britain out of theFrench Revolutionary Wars.As Bonaparte's fleet crossed the Mediterranean, it was pursued by a British force under Nelson who had been sent from the British fleet in theTagusto learn the purpose of the French expedition and to defeat it. He chased the French for more than two months, on several occasions missing them only by a matter of hours. Bonaparte was aware of Nelson's pursuit and enforced absolute secrecy about his destination. He was able tocapture Maltaand then land in Egypt without interception by the British naval forces.

With the French army ashore, the French fleet anchored in Aboukir Bay, 20 miles (32 km) northeast of Alexandria. Commander Vice-Admiral François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers believed that he had established a formidable defensive position. The British fleet arrived off Egypt on 1 August and discovered Brueys's dispositions, and Nelson ordered an immediate attack. His ships advanced on the French line and split into two divisions as they approached. One cut across the head of the line and passed between the anchored French and the shore, while the other engaged the seaward side of the French fleet. Trapped in a crossfire, the leading French warships were battered into surrender during a fierce three-hour battle, although the centre of the line held out for a while until more British ships were able to join the attack. At 22:00, the French flagshipOrientexploded which prompted the rear division of the French fleet to attempt to break out of the bay. With Brueys dead and hisvanguardand centre defeated, only twoships of the lineand twofrigatesescaped from a total of 17 ships engaged.

The battle reversed the strategic situation between the two nations' forces in the Mediterranean and entrenched the Royal Navy in the dominant position that it retained for the rest of theNapoleonic Wars.It also encouraged other European countries to turn against France, and was a factor in the outbreak of theWar of the Second Coalition.Bonaparte's army was trapped in Egypt, and Royal Navy dominance off the Syrian coast contributed significantly to the French defeat at thesiege of Acrein 1799 which preceded Bonaparte's abandonment of Egypt and return to Europe. Nelson was wounded in the battle, and he was proclaimed a hero across Europe and was subsequently madeBaron Nelson—although he was privately dissatisfied with his rewards. His captains were also highly praised and went on to form the nucleus of the legendaryNelson's Band of Brothers.The legend of the battle has remained prominent in the popular consciousness, with perhaps the best-known representation beingFelicia Hemans' 1826 poemCasabianca.

Background[edit]

Napoleon Bonaparte'svictories in northern Italyover theAustrian Empirehelped secure victory for the French in theWar of the First Coalitionin 1797, and Great Britain remained the only major European power still at war with theFrench Republic.[1]TheFrench Directoryinvestigated a number of strategic options to counter British opposition, including projected invasions of Ireland and Britain and the expansion of theFrench Navyto challenge theRoyal Navyat sea.[2]Despite significant efforts, British control ofNorthern Europeanwaters rendered these ambitions impractical in the short term,[3]and the Royal Navy remained firmly in control of theAtlantic Ocean.However, the French navy was dominant in the Mediterranean, following the withdrawal of the British fleet after the outbreak of war between Britain and Spain in 1796.[4]This allowed Bonaparte to propose aninvasion of Egyptas an alternative to confronting Britain directly, believing that the British would be too distracted by an imminentIrish uprisingto intervene in the Mediterranean.[5]

Bonaparte believed that, by establishing a permanent presence inEgypt(nominally part of the neutralOttoman Empire), the French would obtain a staging point for future operations againstBritish India,possibly by means of an alliance with theTipu SultanofSeringapatam,that might successfully drive the British out of the war.[6]The campaign would sever the chain of communication that connected Britain with India, an essential part of theBritish Empirewhose trade generated the wealth that Britain required to prosecute the war successfully.[7]The French Directory agreed with Bonaparte's plans, although a major factor in their decision was a desire to see the politically ambitious Bonaparte and the fiercely loyal veterans of his Italian campaigns travel as far from France as possible.[8]During the spring of 1798, Bonaparte assembled more than 35,000 soldiers in Mediterranean France and Italy and developed a powerful fleet atToulon.He also formed theCommission des Sciences et des Arts,a body of scientists and engineers intended to establish a French colony in Egypt.[9]Napoleon kept the destination of the expedition top secret—most of the army's officers did not know of its target, and Bonaparte did not publicly reveal his goal until the first stage of the expedition was complete.[10]

Mediterranean campaign[edit]

Bonaparte's armada sailed from Toulon on 19 May, making rapid progress through theLigurian Seaand collecting more ships atGenoa,before sailing southwards along theSardiniancoast and passingSicilyon 7 June.[11]On 9 June, the fleet arrived offMalta,then under the ownership of theKnights of St. John of Jerusalem,ruled byGrand MasterFerdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim.[12]Bonaparte demanded that his fleet be permitted entry to the fortified harbour ofValletta.When the Knights refused, the French general responded by ordering alarge scale invasion of the Maltese Islands,overrunning the defenders after 24 hours of skirmishing.[13]The Knights formally surrendered on 12 June and, in exchange for substantial financial compensation, handed the islands and all of their resources over to Bonaparte, including the extensive property of theRoman Catholic Churchon Malta.[14]Within a week, Bonaparte had resupplied his ships, and on 19 June, his fleet departed forAlexandriain the direction ofCrete,leaving 4,000 men at Valletta under GeneralClaude-Henri Vauboisto ensure French control of the islands.[15]

While Bonaparte was sailing to Malta, the Royal Navy re-entered the Mediterranean for the first time in more than a year. Alarmed by reports of French preparations on the Mediterranean coast,Lord Spencerat theAdmiraltysent a message to Vice-AdmiralEarl St. Vincent,commander of the Mediterranean Fleet based in theTagus,to despatch a squadron to investigate.[16]This squadron, consisting of threeships of the lineand threefrigates,was entrusted to Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson.

Nelson was a highly experienced officer who had been blinded in one eye during fighting inCorsicain 1794 and subsequently commended for his capture of two Spanishships of the lineat theBattle of Cape St. Vincentin February 1797. In July 1797, he lost an arm at theBattle of Santa Cruz de Tenerifeand had been forced to return to Britain to recuperate.[17]Returning to the fleet at the Tagus in late April 1798, he was ordered to collect the squadron stationed atGibraltarand sail for the Ligurian Sea.[18]On 21 May, as Nelson's squadron approached Toulon, it was struck by a fierce gale and Nelson's flagship,HMSVanguard,lost its topmasts and was almost wrecked on the Corsican coast.[19]The remainder of the squadron was scattered. The ships of the line sheltered atSan Pietro Islandoff Sardinia; the frigates were blown to the west and failed to return.[20]

On 7 June, following hasty repairs to his flagship, a fleet consisting of ten ships of the line and afourth-ratejoined Nelson off Toulon. The fleet, under the command of CaptainThomas Troubridge,had been sent by Earl St. Vincent to reinforce Nelson, with orders that he was to pursue and intercept the Toulon convoy.[21]Although he now had enough ships to challenge the French fleet, Nelson suffered two great disadvantages: He had no intelligence regarding the destination of the French, and no frigates to scout ahead of his force.[22]Striking southwards in the hope of collecting information about French movements, Nelson's ships stopped atElbaandNaples,where the British ambassador,Sir William Hamilton,reported that the French fleet had passed Sicily headed in the direction of Malta.[23]Despite pleas from Nelson and Hamilton,King Ferdinand of Naplesrefused to lend his frigates to the British fleet, fearing French reprisals.[24]On 22 June, a brig sailing fromRagusabrought Nelson the news that the French had sailed eastwards from Malta on 16 June.[25]After conferring with his captains, the admiral decided that the French target must be Egypt and set off in pursuit.[26]Incorrectly believing the French to be five days ahead rather than two, Nelson insisted on a direct route to Alexandria without deviation.[27]

On the evening of 22 June, Nelson's fleet passed the French in the darkness, overtaking the slow invasion convoy without realising how close they were to their target.[28]Making rapid time on a direct route, Nelson reached Alexandria on 28 June and discovered that the French were not there.[29]After a meeting with the suspicious Ottoman commander, Sayyid Muhammad Kurayyim, Nelson ordered the British fleet northwards, reaching the coast ofAnatoliaon 4 July and turning westwards back towards Sicily.[30]Nelson had missed the French by less than a day—the scouts of the French fleet arrived off Alexandria in the evening of 29 June.[31]

Concerned by his near encounter with Nelson, Bonaparte ordered an immediate invasion, his troops coming ashore in a poorly managedamphibious operationin which at least 20 drowned.[32]Marching along the coast, the French army stormed Alexandria and captured the city,[33]after which Bonaparte led the main force of his army inland.[34]He instructed his naval commander, Vice-AdmiralFrançois-Paul Brueys D'Aigalliers,to anchor in Alexandria harbour, but naval surveyors reported that the channel into the harbour was too shallow and narrow for the larger ships of the French fleet.[35]As a result, the French selected an alternative anchorage atAboukir Bay,20 miles (32 km) northeast of Alexandria.[36]

Nelson's fleet reachedSyracusein Sicily on 19 July and took on essential supplies.[37]There the admiral wrote letters describing the events of the previous months: "It is an old saying, 'the Devil's children have the Devil's luck.' I cannot find, or at this moment learn, beyond vague conjecture where the French fleet are gone to. All my ill fortune, hitherto, has proceeded from want of frigates."[38]Meanwhile, the French were securing Egypt by theBattle of the Pyramids.By 24 July, the British fleet was resupplied and, having determined that the French must be somewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean, Nelson sailed again in the direction of theMorea.[39]On 28 July, atCoron,Nelson finally obtained intelligence describing the French attack on Egypt and turned south across the Mediterranean. His scouts,HMSAlexanderandHMSSwiftsure,sighted the French transport fleet at Alexandria on the afternoon of 1 August.[40]

Aboukir Bay[edit]

WhenAlexandria harbourhad proved inadequate for his fleet, Brueys had gathered his captains and discussed their options. Bonaparte had ordered the fleet to anchor in Aboukir Bay, a shallow and exposed anchorage, but had supplemented the orders with the suggestion that, if Aboukir Bay was too dangerous, Brueys could sail north toCorfu,leaving only the transports and a handful of lighter warships at Alexandria.[41]Brueys refused, in the belief that his squadron could provide essential support to the French army on shore, and called his captains aboard his 120-gun flagshipOrientto discuss their response should Nelson discover the fleet in its anchorage. Despite vocal opposition fromContre-amiralArmand Blanquet,[42]who insisted that the fleet would be best able to respond in open water, the rest of the captains agreed that anchoring in aline of battleinside the bay presented the strongest tactic for confronting Nelson.[43]It is possible that Bonaparte envisaged Aboukir Bay as a temporary anchorage: on 27 July, he expressed the expectation that Brueys had already transferred his ships to Alexandria, and three days later, he issued orders for the fleet to make for Corfu in preparation for naval operations against the Ottoman territories in the Balkans,[44]althoughBedouinpartisans[45]intercepted and killed the courier carrying the instructions.

artist unknown,Palace of Versailles

Aboukir Bay is a coastal indentation 16 nautical miles (30 km) across, stretching from the village ofAbu Qirin the west to the town ofRosettato the east, where one of the mouths of theRiver Nileempties into the Mediterranean.[46]In 1798, the bay was protected at its western end by extensive rockyshoalswhich ran 3 miles (4.8 km) into the bay from apromontoryguarded by Aboukir Castle. A small fort situated onan islandamong the rocks protected the shoals.[47]The fort was garrisoned by French soldiers and armed with at least four cannon and two heavymortars.[48]Brueys had augmented the fort with hisbomb vesselsandgunboats,anchored among the rocks to the west of the island in a position to give support to the head of the French line. Further shoals ran unevenly to the south of the island and extended across the bay in a rough semicircle approximately 1,650 yards (1,510 m) from the shore.[49]These shoals were too shallow to permit the passage of larger warships, and so Brueys ordered his thirteen ships of the line to form up in a line of battle following the northeastern edge of the shoals to the south of the island, a position that allowed the ships to disembark supplies from their port sides while covering the landings with their starboard batteries.[50]Orders were issued for each ship to attach strong cables to the bow and stern of their neighbours, which would effectively turn the line into a long battery forming a theoretically impregnable barrier.[51]Brueys positioned a second, inner line of four frigates approximately 350 yards (320 m) west of the main line, roughly halfway between the line and the shoal. The van of the French line was led byGuerrier,positioned 2,400 yards (2,200 m) southeast of Aboukir Island and about 1,000 yards (910 m) from the edge of the shoals that surrounded the island.[48]The line stretched southeast, with the centre bowed seawards away from the shoal. The French ships were spaced at intervals of 160 yards (150 m) and the whole line was 2,850 yards (2,610 m) long,[52]with the flagshipOrientat the centre and two large 80-gun ships anchored on either side.[53]The rear division of the line was under the command of Contre-amiralPierre-Charles VilleneuveinGuillaume Tell.[48]

In deploying his ships in this way, Brueys hoped that the British would be forced by the shoals to attack his strong centre and rear, allowing his van to use the prevailing northeasterly wind to counterattack the British once they were engaged.[54]However, he had made a serious misjudgement: he had left enough room betweenGuerrierand the shoals for an enemy ship to cut across the head of the French line and proceed between the shoals and the French ships, allowing the unsupported vanguard to be caught in a crossfire by two divisions of enemy ships.[55]Compounding this error, the French only prepared their ships for battle on their starboard (seaward) sides, from which they expected the attack would have to come; their landward port sides were unprepared.[56] The port side gun ports were closed, and the decks on that side were uncleared, with various stored items blocking access to the guns.[57]Brueys' dispositions had a second significant flaw: The 160-yard gaps between ships were large enough for a British ship to push through and break the French line.[58]Furthermore, not all of the French captains had followed Brueys' orders to attach cables to their neighbours' bow and stern, which would have prevented such a manoeuvre.[59]The problem was exacerbated by orders to only anchor at the bow, which allowed the ships to swing with the wind and widened the gaps. It also created areas within the French line not covered by the broadside of any ship. British vessels could anchor in those spaces and engage the French without reply. In addition, the deployment of Brueys' fleet prevented the rear from effectively supporting the van due to the prevailing winds.[60]

A more pressing problem for Brueys was a lack of food and water for the fleet: Bonaparte had unloaded almost all of the provisions carried aboard and no supplies were reaching the ships from the shore. To remedy this, Brueys sent foraging parties of 25 men from each ship along the coast to requisition food, dig wells, and collect water.[51]Constant attacks by Bedouin partisans, however, required escorts of heavily armed guards for each party. Hence, up to a third of the fleet's sailors were away from their ships at any one time.[61]Brueys wrote a letter describing the situation toMinister of MarineÉtienne Eustache Bruix,reporting that "Our crews are weak, both in number and quality. Our rigging, in general, out of repair, and I am sure it requires no little courage to undertake the management of a fleet furnished with such tools."[62]

Battle[edit]

Nelson's arrival[edit]

Although initially disappointed that the main French fleet was not at Alexandria, Nelson knew from the presence of the transports that they must be nearby. At 14:00 on 1 August, lookouts onHMSZealousreported the French anchored in Aboukir Bay, its signal lieutenant just beating the lieutenant onHMSGoliathwith the signal, but inaccurately describing 16 French ships of the line instead of 13.[63]At the same time, French lookouts onHeureux,the ninth ship in the French line, sighted the British fleet approximately nine nautical miles off the mouth of Aboukir Bay. The French initially reported just 11 British ships –SwiftsureandAlexanderwere still returning from their scouting operations at Alexandria, and so were 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) to the west of the main fleet, out of sight.[64]Troubridge's ship,HMSCulloden,was also some distance from the main body, towing a captured merchant ship. At the sight of the French, Troubridge abandoned the vessel and made strenuous efforts to rejoin Nelson.[63]Due to the need for so many sailors to work onshore, Brueys had not deployed any of his lighter warships as scouts, which left him unable to react swiftly to the sudden appearance of the British.[65]

As his ships readied for action, Brueys ordered his captains to gather for a conference onOrientand hastily recalled his shore parties, although most had still not returned by the start of the battle.[64]To replace them, large numbers of men were taken out of the frigates and distributed among the ships of the line.[66]Brueys also hoped to lure the British fleet onto the shoals at Aboukir Island, sending the brigsAlerteandRailleurto act as decoys in the shallow waters.[52]By 16:00,AlexanderandSwiftsurewere also in sight, although some distance from the main British fleet. Brueys gave orders to abandon the plan to remain at anchor and instead for his line to set sail.[67]Blanquet protested the order on the grounds that there were not enough men aboard the French ships to both sail the ships and man the guns.[68]Nelson gave orders for his leading ships to slow down, to allow the British fleet to approach in a more organised formation. This convinced Brueys that rather than risk an evening battle in confined waters, the British were planning to wait for the following day. He rescinded his earlier order to sail.[69]Brueys may have been hoping that the delay would allow him to slip past the British during the night and thus follow Bonaparte's orders not to engage the British fleet directly if he could avoid it.[66]

Nelson ordered the fleet to slow down at 16:00 to allow his ships to rig "springs"on their anchor cables, a system of attaching the bow anchor that increased stability and allowed his ships to swing theirbroadsidesto face an enemy while stationary. It also increased manoeuvrability and therefore reduced the risk of coming underraking fire.[70]Nelson's plan, shaped through discussion with his senior captains during the return voyage to Alexandria,[46]was to advance on the French and pass down the seaward side of the van and centre of the French line, so that each French ship would face two British ships and the massiveOrientwould be fighting against three.[71]The direction of the wind meant that the French rear division would be unable to join the battle easily and would be cut off from the front portions of the line.[72]To ensure that in the smoke and confusion of a night battle his ships would not accidentally open fire on one another, Nelson ordered that each ship prepare four horizontal lights at the head of theirmizzenmast and hoist an illuminatedWhite Ensign,which was different enough from theFrench tricolourthat it would not be mistaken in poor visibility, reducing the risk that British ships might fire on one another in the darkness.[73]As his ship was readied for battle, Nelson held a final dinner withVanguard's officers, announcing as he rose: "Before this time tomorrow I shall have gained apeerageorWestminster Abbey,"[74]in reference to the rewards of victory or the traditional burial place of British military heroes.

Shortly after the French order to set sail was abandoned, the British fleet began rapidly approaching once more. Brueys, now expecting to come under attack that night, ordered each of his ships to place springs on their anchor cables and prepare for action.[64]He sent theAlerteahead, which passed close to the leading British ships and then steered sharply to the west over the shoal, in the hope that the ships of the line might follow and become grounded.[69]None of Nelson's captains fell for the ruse and the British fleet continued undeterred.[71]At 17:30, Nelson hailed one of his two leading ships, HMSZealousunder CaptainSamuel Hood,which had been racingGoliathto be the first to fire on the French. The admiral ordered Hood to establish the safest course into the harbour. The British had no charts of the depth or shape of the bay, except a rough sketch mapSwiftsurehad obtained from a merchant captain, an inaccurate British atlas onZealous,[75]and a 35-year-old French map aboardGoliath.[55]Hood replied that he would take carefulsoundingsas he advanced to test the depth of the water,[76]and that, "If you will allow the honour of leading you into battle, I will keep the lead going."[77]Shortly afterwards, Nelson paused to speak with the brigHMSMutine,whose commander, LieutenantThomas Hardy,had seized somemaritime pilotsfrom a small Alexandrine vessel.[78]AsVanguardcame to a stop, the following ships slowed. This caused a gap to open up betweenZealousandGoliathand the rest of the fleet.[55]To counter this effect, Nelson orderedHMSTheseusunder CaptainRalph Millerto pass his flagship and joinZealousandGoliathin the vanguard.[76]By 18:00, the British fleet was again under full sail,Vanguardsixth in the line of ten ships asCullodentrailed behind to the north andAlexanderandSwiftsurehastened to catch up to the west.[79]Following the rapid change from a loose formation to a rigid line of battle, both fleets raised their colours; each British ship hoisted additionalUnion Flagsin its rigging in case its main flag was shot away.[80]At 18:20, asGoliathandZealousrapidly bore down on them, the leading French shipsGuerrierandConquérantopened fire.[81]

Ten minutes after the French opened fire,Goliath,ignoring fire from the fort tostarboardand fromGuerriertoport,most of which was too high to trouble the ship, crossed the head of the French line.[80]CaptainThomas Foleyhad noticed as he approached that there was an unexpected gap betweenGuerrierand the shallow water of the shoal. On his own initiative, Foley decided to exploit this tactical error and changed his angle of approach to sail through the gap.[77]As the bow ofGuerriercame within range,Goliathopened fire, inflicting severe damage with a double-shotted raking broadside as the British ship turned to port and passed down the unprepared port side ofGuerrier.[59]Foley'sRoyal Marinesand a company of Austriangrenadiersjoined the attack, firing their muskets.[83]Foley had intended to anchor alongside the French ship and engage it closely, but his anchor took too long to descend and his ship passedGuerrierentirely.[84]Goliatheventually stopped close to the bow ofConquérant,opening fire on the new opponent and using the unengaged starboard guns to exchange occasional shots with the frigateSérieuseand bomb vesselHercule,which were anchored inshore of the battle line.[76]

Foley's attack was followed by Hood inZealous,who also crossed the French line and successfully anchored next toGuerrierin the space Foley had intended, engaging the lead ship's bow from close range.[85]Within five minutesGuerrier's foremast had fallen, to cheers from the crews of the approaching British ships.[86]The speed of the British advance took the French captains by surprise; they were still aboardOrientin conference with the admiral when the firing started. Hastily launching their boats, they returned to their vessels. CaptainJean-François-Timothée TrulletofGuerriershouted orders from his barge for his men to return fire onZealous.[85]

The third British ship into action wasHMSOrionunder CaptainSir James Saumarez,which rounded the engagement at the head of the battle line and passed between the French main line and the frigates that lay closer inshore.[87]As he did so, the frigateSérieuseopened fire onOrion,wounding two men. The convention in naval warfare of the time was that ships of the line did not attack frigates when there were ships of equal size to engage, but in firing first French CaptainClaude-Jean Martinhad negated the rule. Saumarez waited until the frigate was at close range before replying.[88]Orionneeded just one broadside to reduce the frigate to a wreck, and Martin's disabled ship drifted away over the shoal.[72]During the delay this detour caused, two other British ships joined the battle:Theseus,which had been disguised as afirst-rateship,[89]followed Foley's track acrossGuerrier's bow. Miller steered his ship through the middle of the melee between the anchored British and French ships until he encountered the third French ship,Spartiate.Anchoring to port, Miller's ship opened fire at close range.HMSAudaciousunder CaptainDavidge Gouldcrossed the French line betweenGuerrierandConquérant,anchoring between the ships and raking them both.[86][Note B]Orionthen rejoined the action further south than intended, firing on the fifth French ship,Peuple Souverain,and Admiral Blanquet's flagship,Franklin.[72]

The next three British ships,Vanguardin the lead followed byHMSMinotaurandHMSDefence,remained in line of battle formation and anchored on the starboard side of the French line at 18:40.[81]Nelson focused his flagship's fire onSpartiate,while CaptainThomas LouisinMinotaurattacked the unengagedAquilonand CaptainJohn PeytoninDefencejoined the attack onPeuple Souverain.[86]With the French vanguard now heavily outnumbered, the following British ships,HMSBellerophonandHMSMajestic,passed by the melee and advanced on the so far unengaged French centre.[90]Both ships were soon fighting enemies much more powerful than they and began to take severe damage. CaptainHenry DarbyonBellerophonmissed his intended anchor nearFranklinand instead found his ship underneath the main battery of the French flagship.[91]CaptainGeorge Blagdon WestcottonMajesticalso missed his station and almost collided withHeureux,coming under heavy fire fromTonnant.Unable to stop in time, Westcott'sjibboombecame entangled withTonnant'sshroud.[92]

The French suffered too, Admiral Brueys onOrientwas severely wounded in the face and hand by flying debris during the opening exchange of fire withBellerophon.[93]The final ship of the British line,Cullodenunder Troubridge, sailed too close to Aboukir Island in the growing darkness and became stuck fast on the shoal.[91]Despite strenuous efforts from theCulloden's boats, the brigMutineand the 50-gunHMSLeanderunder CaptainThomas Thompson,the ship of the line could not be moved, and the waves droveCullodenfurther onto the shoal, inflicting severe damage to the ship's hull.[94]

Surrender of the French vanguard[edit]

At 19:00 the identifying lights in the mizzenmasts of the British fleet were lit. By this time,Guerrierhad been completely dismasted and heavily battered.Zealousby contrast was barely touched: Hood had situatedZealousoutside the arc of most of the French ship's broadsides, and in any caseGuerrierwas not prepared for an engagement on both sides simultaneously, with its port guns blocked by stores.[73]Although their ship was a wreck, the crew ofGuerrierrefused to surrender, continuing to fire the few functional guns whenever possible despite heavy answering fire fromZealous.[95]In addition to his cannon fire, Hood called up his marines and ordered them to fire volleys of musket shot at the deck of the French ship, driving the crew out of sight but still failing to secure the surrender from Captain Trullet. It was not until 21:00, when Hood sent a small boat toGuerrierwith a boarding party, that the French ship finally surrendered.[73]Conquérantwas defeated more rapidly, after heavy broadsides from passing British ships and the close attentions ofAudaciousandGoliathbrought down all three masts before 19:00. With his ship immobile and badly damaged, the mortally wounded CaptainEtienne Dalbaradestruck his coloursand a boarding party seized control.[96]UnlikeZealous,these British ships suffered relatively severe damage in the engagement.Goliathlost most of its rigging, suffered damage to all three masts and suffered more than 60 casualties.[97]With his opponents defeated, Captain Gould onAudaciousused the spring on his cable to transfer fire toSpartiate,the next French ship in line. To the west of the battle the batteredSérieusesank over the shoal. Her masts protruded from the water as survivors scrambled into boats and rowed for the shore.[72]

The transfer ofAudacious's broadside toSpartiatemeant that CaptainMaurice-Julien Emeriaunow faced three opponents. Within minutes all three of his ship's masts had fallen, but the battle aroundSpartiatecontinued until 21:00, when the badly wounded Emeriau ordered his colours struck.[97]AlthoughSpartiatewas outnumbered, it had been supported by the next in line,Aquilon,which was the only ship of the French van squadron fighting a single opponent,Minotaur.CaptainAntoine René Thévenardused the spring on his anchor cable to angle his broadside into a raking position across the bow of Nelson's flagship, which consequently suffered more than 100 casualties, including the admiral.[97]At approximately 20:30, an iron splinter fired in alangrageshot fromSpartiatestruck Nelson over his blinded right eye.[98]The wound caused a flap of skin to fall across his face, rendering him temporarily completely blind.[99]Nelson collapsed into the arms of CaptainEdward Berryand was carried below. Certain that his wound was fatal, he cried out "I am killed, remember me to my wife",[100]and called for his chaplain,Stephen Comyn.[101]The wound was immediately inspected byVanguard's surgeon Michael Jefferson, who informed the admiral that it was a simple flesh wound and stitched the skin together.[102]Nelson subsequently ignored Jefferson's instructions to remain inactive, returning to the quarterdeck shortly before the explosion onOrientto oversee the closing stages of the battle.[103]Although Thévenard's manoeuvre was successful, it placed his own bow underMinotaur's guns and by 21:25 the French ship was dismasted and battered, Captain Thévenard killed and his junior officers forced to surrender.[104]With his opponent defeated, CaptainThomas Louisthen tookMinotaursouth to join the attack onFranklin.[105]

DefenceandOrionattacked the fifth French ship,Peuple Souverain,from either side and the ship rapidly lost the fore and main masts.[104]Aboard theOrion,a wooden block was smashed off one of the ship's masts, killing two men before wounding Captain Saumarez in the thigh.[106]OnPeuple Souverain,CaptainPierre-Paul Raccordwas badly wounded and ordered his ship's anchor cable cut in an effort to escape the bombardment.Peuple Souveraindrifted south towards the flagshipOrient,which mistakenly opened fire on the darkened vessel.[107]OrionandDefencewere unable to immediately pursue.Defencehad lost its fore topmast and an improvisedfireshipthat drifted through the battle narrowly missedOrion.The origin of this vessel, an abandoned and burning ship's boat laden with highly flammable material, is uncertain, but it may have been launched fromGuerrieras the battle began.[104]Peuple Souverainanchored not far fromOrient,but took no further part in the fighting. The wrecked ship surrendered during the night.Franklinremained in combat, but Blanquet had suffered a severe head wound and Captain Gillet had been carried below unconscious with severe wounds. Shortly afterwards, a fire broke out on the quarterdeck after an arms locker exploded, which was eventually extinguished with difficulty by the crew.[108]

To the south, HMSBellerophonwas in serious trouble as the huge broadside ofOrientpounded the ship. At 19:50 the mizzenmast and main mast both collapsed and fires broke out simultaneously at several points.[109]Although the blazes were extinguished, the ship had suffered more than 200 casualties. Captain Darby recognised that his position was untenable and ordered the anchor cables cut at 20:20. The battered ship drifted away from the battle under continued fire fromTonnantas the foremast collapsed as well.[110]Orienthad also suffered significant damage and Admiral Brueys had been struck in the midriff by a cannonball that almost cut him in half.[109]He died fifteen minutes later, remaining on deck and refusing to be carried below.[111]Orient's captain,Luc-Julien-Joseph Casabianca,was also wounded, struck in the face by flying debris and knocked unconscious,[112]while his twelve-year-old son had a leg torn off by a cannonball as he stood beside his father.[113]The most southerly British ship,Majestic,had become briefly entangled with the 80-gunTonnant,[114]and in the resulting battle, suffered heavy casualties. CaptainGeorge Blagdon Westcottwas among the dead, killed by French musket fire.[115]Lieutenant Robert Cuthbert assumed command and successfully disentangled his ship, allowing the badly damagedMajesticto drift further southwards so that by 20:30 it was stationed betweenTonnantand the next in line,Heureux,engaging both.[116]To support the centre, Captain Thompson ofLeanderabandoned the futile efforts to drag the strandedCullodenoff the shoal and sailed down the embattled French line, entering the gap created by the driftingPeuple Souverainand opening a fierce raking fire onFranklinandOrient.[96]

While the battle raged in the bay, the two straggling British ships made strenuous efforts to join the engagement, focusing on the flashes of gunfire in the darkness. Warned away from the Aboukir shoals by the groundedCulloden,CaptainBenjamin HallowellinSwiftsurepassed the melee at the head of the line and aimed his ship at the French centre.[94]Shortly after 20:00, a dismasted hulk was spotted drifting in front ofSwiftsureand Hallowell initially ordered his men to fire before rescinding the order, concerned for the identity of the strange vessel. Hailing the battered ship, Hallowell received the reply "Bellerophon,going out of action disabled. "[116]Relieved that he had not accidentally attacked one of his own ships in the darkness, Hallowell pulled up betweenOrientandFranklinand opened fire on them both.[100]Alexander,the final unengaged British ship, which had followedSwiftsure,pulled up close toTonnant,which had begun to drift away from the embattled French flagship. CaptainAlexander Ballthen joined the attack onOrient.[117]

Destruction ofL'Orient[edit]

At 21:00, the British observed a fire on the lower decks of theOrient,the French flagship.[118]Identifying the danger this posed to theOrient,Captain Hallowell directed his gun crews to fire their guns directly into the blaze. Sustained British gun fire spread the flames throughout the ship's stern and prevented all efforts to extinguish them.[109]Within minutes the fire had ascended the rigging and set the vast sails alight.[117]The nearest British ships,Swiftsure,Alexander,andOrion,all stopped firing, closed their gunports, and began edging away from the burning ship in anticipation of the detonation of the enormous ammunition supplies stored on board.[110]In addition, they took crews away from the guns to form fire parties and to soak the sails and decks in seawater to help contain any resulting fires.[112]Likewise the French shipsTonnant,Heureux,andMercureall cut their anchor cables and drifted southwards away from the burning ship.[119]At 22:00 the fire reached themagazines,and theOrientwas destroyed by a massive explosion. The concussion of the blast was powerful enough to rip open the seams of the nearest ships,[120]and flaming wreckage landed in a huge circle, much of it flying directly over the surrounding ships into the sea beyond.[121]Falling wreckage started fires onSwiftsure,Alexander,andFranklin,although in each case teams of sailors with water buckets succeeded in extinguishing the flames,[109]despite a secondary explosion onFranklin.[122]

It has never been firmly established how the fire onOrientbroke out, but one common account is that jars of oil and paint had been left on thepoop deck,instead of being properly stowed after painting of the ship's hull had been completed shortly before the battle. Burningwaddingfrom one of the British ships is believed to have floated onto the poop deck and ignited the paint. The fire rapidly spread through the admiral's cabin and into a ready magazine that storedcarcassammunition, which was designed to burn more fiercely in water than in air.[93]Alternatively, Fleet CaptainHonoré Ganteaumelater reported the cause as an explosion on the quarterdeck, preceded by a series of minor fires on the main deck among the ship's boats.[123]Whatever its origin, the fire spread rapidly through the ship's rigging, unchecked by the fire pumps aboard, which had been smashed by British shot.[124]A second blaze then began at the bow, trapping hundreds of sailors in the ship's waist.[120]Subsequent archaeological investigation found debris scattered over 500 metres (550 yd) of seabed and evidence that the ship was wracked by two explosions.[125]Hundreds of men dived into the sea to escape the flames, but fewer than 100 survived the blast. British boats picked up approximately 70 survivors, including the wounded staff officerLéonard-Bernard Motard.A few others, including Ganteaume, managed to reach the shore on rafts.[93]The remainder of the crew, numbering more than 1,000 men, were killed,[126]including Captain Casabianca and his son, Giocante.[127]

For ten minutes after the explosion there was no firing; sailors from both sides were either too shocked by the blast or desperately extinguishing fires aboard their own ships to continue the fight.[121]During the lull, Nelson gave orders that boats be sent to pull survivors from the water around the remains ofOrient.At 22:10,Franklinrestarted the engagement by firing onSwiftsure.[128]Isolated and battered, Blanquet's ship was soon dismasted and the admiral, suffering a severe head wound, was forced to surrender by the combined firepower ofSwiftsureandDefence.[129]More than half ofFranklin's crew had been killed or wounded.[122]

By midnight onlyTonnantremained engaged, as CommodoreAristide Aubert Du Petit Thouarscontinued his fight withMajesticand fired onSwiftsurewhen the British ship moved within range. By 03:00, after more than three hours of close quarter combat,Majestichad lost its main and mizzen masts whileTonnantwas a dismasted hulk.[121]Although Captain Du Petit Thouars had lost both legs and an arm he remained in command, insisting on having the tricolour nailed to the mast to prevent it from being struck and giving orders from his position propped up on deck in a bucket of wheat.[129]Under his guidance, the batteredTonnantgradually drifted southwards away from the action to join the southern division under Villeneuve, who failed to bring these ships into effective action.[130]Throughout the engagement the French rear had kept up an arbitrary fire on the battling ships ahead. The only noticeable effect was the smashing ofTimoléon's rudder by misdirected fire from the neighbouringGénéreux.[131]

Morning[edit]

As the sun rose at 04:00 on 2 August, firing broke out once again between the French southern division ofGuillaume Tell,Tonnant,GénéreuxandTimoléonand the batteredAlexanderandMajestic.[132]Although briefly outmatched, the British ships were soon joined byGoliathandTheseus.As Captain Miller manoeuvred his ship into position,Theseusbriefly came under fire from the frigateArtémise.[128]Miller turned his ship towardsArtémise,but CaptainPierre-Jean Standeletstruck his flag and ordered his men to abandon the frigate. Miller sent a boat under LieutenantWilliam Hosteto take possession of the empty vessel, but Standelet had set fire to his ship as he left andArtémiseblew up shortly afterwards.[133]The surviving French ships of the line, covering their retreat with gunfire, gradually pulled to the east away from the shore at 06:00.Zealouspursued, and was able to prevent the frigateJusticefrom boardingBellerophon,which was anchored at the southern point of the bay undergoing hasty repairs.[130]

Two other French ships still flew the tricolour, but neither was in a position to either retreat or fight. WhenHeureuxandMercurehad cut their anchor cables to escape the explodingOrient,their crews had panicked and neither captain (both of whom were wounded) had managed to regain control of his ship. As a result, both vessels had drifted onto the shoal.[134]Alexander,Goliath,TheseusandLeanderattacked the stranded and defenceless ships, and both surrendered within minutes.[132]The distractions provided byHeureux,MercureandJusticeallowed Villeneuve to bring most of the surviving French ships to the mouth of the bay at 11:00.[135]On the dismastedTonnant,Commodore Du Petit Thouars was now dead from his wounds and thrown overboard at his own request.[106]As the ship was unable to make the required speed it was driven ashore by its crew.Timoléonwas too far south to escape with Villeneuve and, in attempting to join the survivors, had also grounded on the shoal. The force of the impact dislodged the ship's foremast.[136]The remaining French vessels: the ships of the lineGuillaume TellandGénéreuxand the frigatesJusticeandDiane,formed up and stood out to sea, pursued byZealous.[103]Despite strenuous efforts, Captain Hood's isolated ship came under heavy fire and was unable to cut off the trailingJusticeas the French survivors escaped seawards.[135]Zealouswas struck by a number of French shot and lost one man killed.[137]

For the remainder of 2 August Nelson's ships made improvised repairs and boarded and consolidated theirprizes.Cullodenespecially required assistance. Troubridge, having finally dragged his ship off the shoal at 02:00, found that he had lost his rudder and was taking on more than 120 long tons (122 t) of water an hour. Emergency repairs to the hull and fashioning a replacement rudder from a spare topmast took most of the next two days.[138]On the morning of 3 August, Nelson sentTheseusandLeanderto force the surrender of the groundedTonnantandTimoléon.TheTonnant,its decks crowded with 1,600 survivors from other French vessels, surrendered as the British ships approached whileTimoléonwas set on fire by its remaining crew who then escaped to the shore in small boats.[139]Timoléonexploded shortly after midday, the eleventh and final French ship of the line destroyed or captured during the battle.[136]

Aftermath[edit]

"[I] went on deck to view the state of the fleets, and an awful sight it was. The whole bay was covered with dead bodies, mangled, wounded and scorched, not a bit of clothes on them except their trousers."

— Account by Seaman John Nicol ofGoliath,[140]

British casualties in the battle were recorded with some accuracy in the immediate aftermath as 218 killed and approximately 677 wounded, although the number of wounded who subsequently died is not known.[139]The ships that suffered most wereBellerophonwith 201 casualties andMajesticwith 193. Other thanCullodenthe lightest loss was onZealous,which had one man killed and seven wounded.[47]

The casualty list included Captain Westcott, five lieutenants and ten junior officers among the dead, and Admiral Nelson, Captains Saumarez, Ball and Darby, and six lieutenants wounded.[141]Other thanCulloden,the only British ships seriously damaged in their hulls wereBellerophon,Majestic,andVanguard.BellerophonandMajesticwere the only ships to lose masts:Majesticthe main and mizzen andBellerophonall three.[142]

French casualties are harder to calculate but were significantly higher. Estimates of French losses range from 2,000 to 5,000, with a suggested median point of 3,500, which includes more than 1,000 captured wounded and nearly 2,000 killed, half of whom died onOrient.[Note A]In addition to Admiral Brueys killed and Admiral Blanquet wounded, four captains died and seven others were seriously wounded. The French ships suffered severe damage: Two ships of the line and two frigates were destroyed (as well as a bomb vessel scuttled by its crew),[143]and three other captured ships were too battered ever to sail again. Of the remaining prizes, only three were ever sufficiently repaired for frontline service. For weeks after the battle, bodies washed up along the Egyptian coast, decaying slowly in the intense, dry heat.[144]

Nelson, who on surveying the bay on the morning of 2 August said, "Victory is not a name strong enough for such a scene",[145]remained at anchor in Aboukir Bay for the next two weeks, preoccupied with recovering from his wound, writing dispatches, and assessing the military situation in Egypt using documents captured on board one of the prizes.[146]Nelson's head wound was recorded as being "three inches long" with "the cranium exposed for one inch". He suffered pain from the injury for the rest of his life and was badly scarred, styling his hair to disguise it as much as possible.[147]As their commander recovered, his men stripped the wrecks of useful supplies and made repairs to their ships and prizes.[148]

Throughout the week, Aboukir Bay was surrounded by bonfires lit by Bedouin tribesmen in celebration of the British victory.[144]On 5 August,Leanderwas despatched toCadizwith messages for Earl St. Vincent carried by Captain Edward Berry.[149]Over the next few days the British landed all but 200 of the captured prisoners on shore under strict terms ofparole,although Bonaparte later ordered them to be formed into an infantry unit and added to his army.[148]The wounded officers taken prisoner were held on boardVanguard,where Nelson regularly entertained them at dinner. Historian Joseph Allen recounts that on one occasion Nelson, whose eyesight was still suffering following his wound, offered toothpicks to an officer who had lost his teeth and then passed asnuff-boxto an officer whose nose had been torn off, causing much embarrassment.[150]On 8 August the fleet's boats stormed Aboukir Island, which surrendered without a fight. The landing party removed four of the guns and destroyed the rest along with the fort they were mounted in, renaming the island "Nelson's Island".[148]

On 10 August, Nelson sent Lieutenant Thomas Duval fromZealouswith messages to the government in India. Duval travelled across the Middle East overland viacamel traintoAleppoand took theEast India CompanyshipFlyfromBasratoBombay,acquaintingGovernor-General of IndiaViscount Wellesleywith the situation in Egypt.[151]On 12 August the frigatesHMSEmeraldunder Captain Thomas Moutray Waller andHMSAlcmeneunder CaptainGeorge Johnstone Hope,and the sloopHMSBonne Citoyenneunder Captain Robert Retalick, arrived off Alexandria.[152]Initially the British mistook the frigate squadron for French warships andSwiftsurechased them away. They returned the following day once the error had been realised.[148]The same day as the frigates arrived, Nelson sentMutineto Britain with dispatches, under the command of LieutenantThomas Bladen Capel,who had replaced Hardy after the latter's promotion to captain ofVanguard.On 14 August, Nelson sentOrion,Majestic,Bellerophon,Minotaur,Defence,Audacious,Theseus,Franklin,Tonnant,Aquilon,Conquérant,Peuple Souverain,andSpartiateto sea under the command of Saumarez. Many ships had onlyjury mastsand it took a full day for the convoy to reach the mouth of the bay, finally sailing into open water on 15 August. On 16 August the British burned and destroyed the grounded prizeHeureuxas no longer fit for service and on 18 August also burnedGuerrierandMercure.[148]On 19 August, Nelson sailed for Naples withVanguard,Culloden,andAlexander,leaving Hood in command ofZealous,Goliath,Swiftsure,and the recently joined frigates to watch over French activities at Alexandria.[153]

The first message to reach Bonaparte regarding the disaster that had overtaken his fleet arrived on 14 August at his camp on the road betweenSalahiehandCairo.[144]The messenger was a staff officer sent by the Governor of Alexandria GeneralJean Baptiste Kléber,and the report had been hastily written by Admiral Ganteaume, who had subsequently rejoined Villeneuve's ships at sea. One account reports that when he was handed the message, Bonaparte read it without emotion before calling the messenger to him and demanding further details. When the messenger had finished, the French general reportedly announced"Nous n'avons plus de flotte: eh bien. Il faut rester en ces contrées, ou en sortir grands comme les anciens"( "We no longer have a fleet: well, we must either remain in this country or quit it as great as the ancients" ).[153]Another story, as told by the general's secretary,Bourienne,claims that Bonaparte was almost overcome by the news and exclaimed "Unfortunate Brueys, what have you done!"[154]Bonaparte later placed much of the blame for the defeat on the wounded Admiral Blanquet, falsely accusing him of surrenderingFranklinwhile his ship was undamaged. Protestations from Ganteaume and Minister Étienne Eustache Bruix later reduced the degree of criticism Blanquet faced, but he never again served in a command capacity.[153]Bonaparte's most immediate concern however was with his own officers, who began to question the wisdom of the entire expedition. Inviting his most senior officers to dinner, Bonaparte asked them how they were. When they replied that they were "marvellous," Bonaparte responded that it was just as well, since he would have them shot if they continued "fostering mutinies and preaching revolt."[155]To quell any uprising among the native inhabitants, Egyptians overheard discussing the battle were threatened with having their tongues cut out.[156]

Reaction[edit]

Nelson's first set of dispatches were captured whenLeanderwas intercepted and defeated byGénéreuxin a fierce engagement off the western shore of Creteon 18 August 1798.[65]As a result, reports of the battle did not reach Britain until Capel arrived inMutineon 2 October,[152]entering the Admiralty at 11:15 and personally delivering the news to Lord Spencer,[157]who collapsed unconscious when he heard the report.[158]Although Nelson had previously been castigated in the press for failing to intercept the French fleet, rumours of the battle had begun to arrive in Britain from the continent in late September and the news Capel brought was greeted with celebrations right across the country.[159]Within four days Nelson had been elevated to Baron Nelson of the Nile and Burnham Thorpe, a title with which he was privately dissatisfied, believing his actions deserved better reward.[160]King George IIIaddressed theHouses of Parliamenton 20 November with the words:

The unexampled series of our naval triumphs has received fresh splendour from the memorable and decisive action, in which a detachment of my fleet, under the command of Rear-Admiral Lord Nelson, attacked, and almost totally destroyed a superior force of the enemy, strengthened by every advantage of situation. By this great and brilliant victory, an enterprise, of which the injustice, perfidy, and extravagance had fixed the attention of the world, and which was peculiarly directed against some of the most valuable interests of the British empire, has, in the first instance, been turned to the confusion of its authors and the blow thus given to the power and influence of France, has afforded an opening, which, if improved by suitable exertions on the part of other powers, may lead to the general deliverance of Europe.

— King George III, quoted inWilliam James'The Naval History of Great Britain during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars,Volume 2, 1827,[161]

Saumarez's convoy of prizes stopped first at Malta, where Saumarez provided assistance to a rebellion on the island among theMaltese population.[162]It then sailed to Gibraltar, arriving on 18 October to the cheers of the garrison. Saumarez wrote that, "We can never do justice to the warmth of their applause, and the praises they all bestowed on our squadron." On 23 October, following the transfer of the wounded to the military hospital and provision of basic supplies, the convoy sailed on towardsLisbon,leavingBellerophonandMajesticbehind for more extensive repairs.[163]Peuple Souverainalso remained at Gibraltar: The ship was deemed too badly damaged for the Atlantic voyage to Britain and so was converted to a guardship under the name of HMSGuerrier.[60]The remaining prizes underwent basic repairs and then sailed for Britain, spending some months at theTagusand joining with the annual merchant convoy from Portugal in June 1799 under the escort of a squadron commanded by AdmiralSir Alan Gardner,[164]before eventually arriving atPlymouth.Their age and battered state meant that neitherConquérantnorAquilonwere considered fit for active service in the Royal Navy and both were subsequently hulked, although they had been bought into the service for £20,000 (the equivalent of £2.5 million as of 2023)[165]each as HMSConquerantand HMSAboukirto provide a financial reward to the crews that had captured them.[166]Similar sums were also paid out forGuerrier,Mercure,HeureuxandPeuple Souverain,while the other captured ships were worth considerably more. Constructed of Adriaticoak,Tonnanthad been built in 1792 andFranklinandSpartiatewere less than a year old.TonnantandSpartiate,both of which later fought at theBattle of Trafalgar,joined the Royal Navy under their old names whileFranklin,considered to be "the finest two-decked ship in the world",[166]was renamed HMSCanopus.[167]The total value of the prizes captured at the Nile and subsequently bought into the Royal Navy was estimated at just over £130,000 (the equivalent of £16.1 million as of 2023).[163]

Additional awards were presented to the British fleet: Nelson was awarded £2,000 (£270,000 as of 2023) a year for life by theParliament of Great Britainand £1,000 per annum by theParliament of Ireland,[168]although the latter was inadvertently discontinued after theAct of Uniondissolved the Irish Parliament.[169]Both parliaments gave unanimous votes of thanks, each captain who served in the battle was presented with a specially minted gold medal and the first lieutenant of every ship engaged in the battle was promoted to commander.[152]Troubridge and his men, initially excluded, received equal shares in the awards after Nelson personally interceded for the crew of the strandedCulloden,even though they did not directly participate in the engagement.[168]TheHonourable East India Companypresented Nelson with £10,000 (£1,330,000 as of 2023) in recognition of the benefit his action had on their holdings and the cities ofLondon,Liverpooland other municipal and corporate bodies made similar awards.[168]Nelson's own captains presented him with a sword and a portrait as "proof of their esteem." Nelson publicly encouraged this close bond with his officers and on 29 September 1798 described them as "We few, we happy few, we band of brothers", echoingWilliam Shakespeare's playHenry V.From this grew the notion of theNelsonic Band of Brothers,a cadre of high-quality naval officers that served with Nelson for the remainder of his life.[170]Nearly five decades later the battle was among the actions recognised by a clasp attached to theNaval General Service Medal,awarded upon application to all British participants still living in 1847.[171]

Other rewards were bestowed by foreign states, particularly theOttoman EmperorSelim III,who made Nelson the first Knight Commander of the newly createdOrder of the Crescent,and presented him with achelengk,a diamond studded rose, a sable fur and numerous other valuable presents. TsarPaul I of Russiasent, among other rewards, a gold box studded with diamonds, and similar gifts in silver arrived from other European rulers.[172]On his return to Naples, Nelson was greeted with a triumphal procession led byKing Ferdinand IVand Sir William Hamilton and was introduced for only the third time to Sir William's wifeEmma, Lady Hamilton,who fainted violently at the meeting,[173]and apparently took several weeks to recover from her injuries.[158]Lauded as a hero by the Neapolitan court, Nelson was later to dabble in Neapolitan politics and become the Duke of Bronté, actions for which he was criticised by his superiors and his reputation suffered.[174]British generalJohn Moore,who met Nelson in Naples at this time, described him as "covered with stars, medals and ribbons, more like a Prince of Opera than the Conqueror of the Nile."[175]

Rumours of a battle first appeared in the French press as early as 7 August, although credible reports did not arrive until 26 August, and even these claimed that Nelson was dead and Bonaparte a British prisoner.[176]When the news became certain, the French press insisted that the defeat was the result both of an overwhelmingly large British force and unspecified "traitors."[134]Among the anti-government journals in France, the defeat was blamed on the incompetence of the French Directory and on supposed lingering Royalist sentiments in the Navy.[177]Villeneuve came under scathing attack on his return to France for his failure to support Brueys during the battle. In his defence, he pleaded that the wind had been against him and that Brueys had not issued orders for him to counterattack the British fleet.[178]Writing many years later, Bonaparte commented that if the French Navy had adopted the same tactical principles as the British:

Admiral Villeneuve would not have thought himself blameless at Aboukir, for remaining inactive with five or six ships, that is to say, with half the squadron, for twenty four hours, whilst the enemy was overpowering the other wing.

— Napoleon Bonaparte,Mémoires,Volume 1, 1823. Quoted in translation in Noel Mostert'sThe Line Upon a Wind,2007,[179]

By contrast, the British press were jubilant; many newspapers sought to portray the battle as a victory for Britain over anarchy, and the success was used to attack the supposedly pro-republicanWhigpoliticiansCharles James FoxandRichard Brinsley Sheridan.[180]

In the United States, the outcome of the battle led PresidentJohn Adamsto pursue diplomacy with France to end theQuasi-War,as the French naval defeat rendered the prospect of aninvasion of the United Statesless likely.[181]

There has been extensive historiographical debate over the comparative strengths of the fleets, although they were ostensibly evenly matched in size, each containing 13 ships of the line.[182]However, the loss ofCulloden,the relative sizes ofOrientandLeanderand the participation in the action by two of the French frigates and several smaller vessels, as well as the theoretical strength of the French position,[68]leads most historians to the conclusion that the French were marginally more powerful.[64]This is accentuated by theweight of broadsideof several of the French ships:Spartiate,Franklin,Orient,TonnantandGuillaume Tellwere each significantly larger than any individual British ship in the battle.[141]However inadequate deployment, reduced crews, and the failure of the rear division under Villeneuve to meaningfully participate, all contributed to the French defeat.[183]

Effects[edit]

The Battle of the Nile has been called "arguably, the most decisive naval engagement of the great age of sail",[184]and "the most splendid and glorious success which the British Navy gained."[185]Historian and novelistC. S. Forester,writing in 1929, compared the Nile to the great naval actions in history and concluded that "it still only stands rivalled byTsu-Shimaas an example of the annihilation of one fleet by another of approximately equal material force ".[186]The effect on the strategic situation in the Mediterranean was immediate, reversing the balance of the conflict and giving the British control at sea that they maintained for the remainder of the war.[187]The destruction of the French Mediterranean fleet allowed the Royal Navy to return to the sea in force, as British squadrons set upblockadesoff French and allied ports.[188]In particular, British ships cut Malta off from France, aided by the rebellion among the native Maltese population that forced the French garrison to retreat to Valletta and shut the gates.[189]The ensuingsiege of Maltalasted for two years before the defenders were finally starved into surrender.[190]In 1799, British ships harassed Bonaparte's army as it marched east and north throughPalestine,and played a crucial part in Bonaparte's defeat at thesiege of Acre,when the barges carrying the siege train were captured and the French storming parties were bombarded by British ships anchored offshore.[191]It was during one of these latter engagements that Captain Miller ofTheseuswas killed in an ammunition explosion.[192]The defeat at Acre forced Bonaparte to retreat to Egypt and effectively ended his efforts to carve an empire in the Middle East.[193]The French general returned to France without his army late in the year, leaving Kléber in command of Egypt.[194]

TheOttoman Empire,with whom Bonaparte had hoped to conduct an alliance once his control of Egypt was complete, was encouraged by the Battle of the Nile to go to war against France.[195]This led to a series of campaigns that slowly sapped the strength from the French army trapped in Egypt. The British victory also encouraged theAustrian Empireand theRussian Empire,both of whom were mustering armies as part of aSecond Coalition,which declared war on France in 1799.[58]With the Mediterranean undefended, anImperial Russian Navyfleet entered theIonian Sea,while Austrian armies recaptured much of the Italian territory lost to Bonaparte in the previous war.[196]Without their best general and his veterans, the French suffered a series of defeats and it was not until Bonaparte returned to becomeFirst Consulthat France once again held a position of strength onContinental Europe.[197]In 1801 a British Expeditionary Force defeated the demoralised remains of the French army in Egypt. The Royal Navy used its dominance in the Mediterranean to invade Egypt without the fear of ambush while anchored off the Egyptian coast.[198]

In spite of the overwhelming British victory in the climactic battle, the campaign has sometimes been considered a strategic success for France. HistorianEdward Ingramnoted that if Nelson had successfully intercepted Bonaparte at sea as ordered, the ensuing battle could have annihilated both the French fleet and the transports. As it was, Bonaparte was free to continue the war in the Middle East and later to return to Europe personally unscathed.[199]The potential of a successful engagement at sea to change the course of history is underscored by the list of French army officers carried aboard the convoy who later formed the core of the generals and marshals under Emperor Napoleon. In addition to Bonaparte himself,Louis-Alexandre Berthier,Auguste de Marmont,Jean Lannes,Joachim Murat,Louis Desaix,Jean Reynier,Antoine-François Andréossy,Jean-Andoche Junot,Louis-Nicolas DavoutandDumaswere all passengers on thecramped Mediterranean crossing.[200]

Legacy[edit]

The Battle of the Nile remains one of the Royal Navy's most famous victories,[201]and has remained prominent in the British popular imagination, sustained by its depiction in a large number of cartoons, paintings, poems, and plays.[202]One of the best known poems about the battle isCasabianca,which was written byFelicia Dorothea Hemansin 1826 and describes a fictional account of the death of Captain Casabianca's son onOrient.[203]

Monuments were raised, includingCleopatra's Needlein London.Muhammad Ali of Egyptgave the monument in 1819 in recognition of the battle of 1798 and the campaign of 1801 but Great Britain did not erect it on theVictoria Embankmentuntil 1878.[204]Another memorial, theNile ClumpsnearAmesbury,consists of stands ofbeechtrees purportedly planted byLord Queensburyat the behest of Lady Hamilton andThomas Hardyafter Nelson's death. The trees form a plan of the battle; each clump represents the position of a British or French ship.[205]

On the Hall Place estate, Burchetts Green, Berkshire (nowBerkshire College of Agriculture), a double line of oak trees, each tree representing a ship of the opposing fleets, was planted by William East, Baronet, in celebration of the victory. He also constructed a scale-sized pyramid and a life-sized statue of Nelson on the highest point of the estate.

The composerJoseph Haydnhad just completed theMissa in Angustiis(mass for troubled times) afterNapoleon Bonapartehad defeated the Austrian army in four major battles. The well received news of France's defeat at the Nile however resulted in the mass gradually acquiring the nicknameLord Nelson Mass.The title became indelible when, in 1800, Nelson himself visited thePalais Esterházy,accompanied by his mistress,Lady Hamilton,and may have heard the mass performed.[206]

The Royal Navy commemorated the battle with the ship namesHMSAboukir,HMSNileandHMSCanopus,[207]and in 1998 commemorated the 200th anniversary of the battle with a visit to Aboukir Bay by the modern frigateHMSSomerset,whose crew laid wreaths in memory of those who lost their lives in the battle.[208]

- Archaeology

Although Nelson biographerErnle Bradfordassumed in 1977 that the remains ofOrient"are almost certainly unrecoverable,"[209]the first archaeological investigation into the battle began in 1983, when a French survey team under Jacques Dumas discovered the wreck of the French flagship.Franck Goddiolater took over the work, leading a major project to explore the bay in 1998. He found that material was scattered over an area 500 metres (550 yd) in diameter. In addition to military and nautical equipment, Goddio recovered a large number of gold and silver coins from countries across the Mediterranean, some from the 17th century. It is likely that these were part of the treasure taken from Malta that was lost in the explosion aboardOrient.[210]In 2000, Italian archaeologist Paolo Gallo led an excavation focusing on ancient ruins on Nelson's Island. It uncovered a number of graves that date from the battle, as well as others buried there during the 1801 invasion.[211]These graves, which included a woman and three children, were relocated in 2005 to a cemetery atShatbyin Alexandria. The reburial was attended by sailors from the modern frigateHMSChathamand a band from theEgyptian Navy,as well as a descendant of the only identified burial, Commander James Russell.[212]

Notes[edit]

- ^Note A:Sources often give casualty figures for the battle that vary significantly:Roy and Lesley Adkinslist British losses as 218 killed and 677 wounded, French as 5,235 killed or missing and 3,305 captured including approximately 1,000 wounded men.[154]TheDictionnaire des batailles navales franco-anglaises(Dictionary of French-English naval battles) by Jean-Claude Castex, published in 2003, gives British losses as 1,000 casualties or 12% of British personnel engaged and French losses as 1,700 killed, 1,500 wounded and 1,000 prisoners, or 81% of the total French personnel engaged.[213]William Laird Clowesgives precise figures for each British ship, totalling 218 killed and 678 wounded, and quotes French casualty estimates of 2,000 to 5,000, settling on the median average of 3,500.[141]Juan Colegives 218 British dead and French losses of approximately 1,700 dead, a thousand wounded and 3,305 prisoners, most of whom were returned to Alexandria.[214]Robert Gardiner gives British losses as 218 killed and 617 wounded, French as 1,600 killed and 1,500 wounded.[167]William Jamesgives a precise breakdown of British casualties that totals 218 killed and 678 wounded and also quotes estimates of French losses of 2,000 to 5,000, favouring the lower estimate.[93]John Keegangives British losses as 208 killed and 677 wounded and French as several thousand dead and 1,000 wounded.[126]Steven Maffeo vaguely records 1,000 British and 3,000 French casualties.[215]Noel Mostert gives British losses of 218 killed and 678 wounded and quotes estimates of French losses between 2,000 and 5,000.[216]Peter Padfield gives British losses of 218 killed and 677 wounded and French as 1,700 killed and approximately 850 wounded.[188]Digby Smith lists British losses of 218 killed and 678 wounded and French as 2,000 killed, 1,100 wounded and 3,900 captured.[217]Oliver Warnergives figures of British losses of 218 killed and 677 wounded and 5,265 French killed or missing, with 3,105 taken prisoner. Almost all of the French prisoners were returned to French-held territory in Egypt during the week following the battle.[143]

- ^Note B:The courseAudacioustook to reach the battle has been the source of some debate:William Laird Clowesstates thatAudaciouspassed betweenGuerrierandConquerantand anchored in the middle.[86]However, a number of maps of the battle showAudacious's course as rounding the head of the line acrossGuerrier's bow before turning back to port between the leading French ships.[218]Most sources, including Warner and James, are vague on the subject and do not state one way or another. The cause of this discrepancy is likely the lack of any significant account or report on the action from Gould. Gould has been criticised for the placement of his ship during the opening stages of the battle, as the ships he attacked were already outnumbered, and the following day he had to be repeatedly ordered to rejoin the battle as it spread southwards despite the lack of damage to his ship.Oliver Warnerdescribes him as "brave enough no doubt, but without imagination, or any sense of what was happening in the battle as a whole."[219]

References[edit]

- ^Maffeo, p. 224

- ^James, p. 113

- ^Padfield, p. 116

- ^Keegan, p. 36

- ^Rose, p. 141

- ^Adkins, p. 7

- ^Maffeo, p. 230

- ^Rodger, p. 457

- ^Cole, p. 17

- ^Cole, p. 11

- ^Clowes, p. 353

- ^Cole, p. 8

- ^Gardiner, p. 21

- ^James, p. 151

- ^Adkins, p. 13

- ^Maffeo, p. 233

- ^Padfield, p. 109

- ^James, p. 148

- ^Keegan, p. 44

- ^Adkins, p. 9

- ^Maffeo, p. 241

- ^Clowes, p. 354

- ^Gardiner, p. 29

- ^Bradford, p. 176

- ^Mostert, p. 254

- ^Keegan, p. 55

- ^Rodger, p. 459

- ^Maffeo, p. 258

- ^James, p. 154

- ^Keegan, p. 59

- ^Gardiner, p. 26

- ^Adkins, p. 17

- ^Cole, p. 22

- ^Clowes, p. 356

- ^Adkins, p. 21

- ^Mostert, p. 257

- ^James, p. 155

- ^Adkins, p. 19

- ^Maffeo, p. 265

- ^Clowes, p. 355

- ^Rose, p. 142

- ^Bradford, p. 199

- ^James, p. 159

- ^Rose, p. 143

- ^Bradford, p. 192

- ^abMaffeo, p. 268–269

- ^abClowes, p. 357

- ^abcJames, p. 160

- ^Clowes, p. 358

- ^Gardiner, p. 31

- ^abWarner, p. 66

- ^abClowes, p. 359

- ^Mostert, p. 260

- ^Padfield, p. 120

- ^abcAdkins, p. 24

- ^George A. Henty,At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt,Fireship Press, 2008, p. 295.

- ^R.G. Grant,Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare,DK Publications, 2011, p. 180.

- ^abGardiner, p. 13

- ^abKeegan, p. 63

- ^abClowes, p. 372

- ^Mostert, p. 261

- ^Adkins, p. 22

- ^abPadfield, p. 118

- ^abcdAdkins, p. 23

- ^abRodger, p. 460

- ^abJames, p. 161

- ^Mostert, p. 265

- ^abWarner, p. 72

- ^abBradford, p. 200

- ^Clowes, p. 360

- ^abJames, p. 162

- ^abcdJames, p. 165

- ^abcJames, p. 166

- ^Padfield, p. 119

- ^Maffeo, p. 269

- ^abcClowes, p. 361

- ^abBradford, p. 202

- ^Padfield, p. 123

- ^James, p. 163

- ^abJames, p. 164

- ^abGardiner, p. 33

- ^Based upon a map fromKeegan, p. 43

- ^Warner, p. 102

- ^Mostert, p. 266

- ^abAdkins, p. 25

- ^abcdClowes, p. 362

- ^Padfield, p. 124

- ^Adkins, p. 26

- ^Warner, p. 109

- ^Padfield, p. 127

- ^abAdkins, p. 28

- ^Bradford, p. 204

- ^abcdJames, p. 176

- ^abClowes, p. 363

- ^Mostert, p. 267

- ^abClowes, p. 364

- ^abcJames, p. 167

- ^Warner, p. 92

- ^James, p. 175

- ^abAdkins, p. 29

- ^Bradford, p. 205

- ^Adkins, p. 31

- ^abGardiner, p. 38

- ^abcJames, p. 168

- ^Clowes, p. 365

- ^abAdkins, p. 30

- ^Germani, p. 59

- ^Warner, p. 94

- ^abcdClowes, p. 366

- ^abGardiner, p. 34

- ^Germani, p. 58

- ^abPadfield, p. 129

- ^Warner, p. 88

- ^Padfield, p. 128

- ^Mostert, p. 268

- ^abJames, p. 169

- ^abJames, p. 170

- ^Keegan, p. 64

- ^Keegan, p. 65

- ^abMostert, p. 270

- ^abcJames, p. 171

- ^abMostert, p. 271

- ^Adkins, p. 34

- ^Adkins, p. 35

- ^Franck Goddio."Napoleon Bonaparte's Fleet".Retrieved10 March2022.

- ^abKeegan, p. 66

- ^Mostert, p. 269

- ^abGardiner, p. 36

- ^abClowes, p. 367

- ^abJames, p. 172

- ^Germani, p. 60

- ^abClowes, p. 368

- ^Warner, p. 111

- ^abGermani, p. 61

- ^abJames, p. 173

- ^abMostert, p. 272

- ^Allen, p. 212

- ^James, p. 178

- ^abAdkins, p. 37

- ^Warner, p. 103

- ^abcClowes, p. 370

- ^Clowes, p. 369

- ^abWarner, p. 121

- ^abcCole, p. 110

- ^Warner, p. 95

- ^Maffeo, p. 273

- ^Warner, p. 104

- ^abcdeJames, p. 183

- ^James, p. 182

- ^Allen, p. 213

- ^Woodman, p. 115

- ^abcClowes, p. 373

- ^abcJames, p. 184

- ^abAdkins, p. 38

- ^Cole, p. 111

- ^Cole, p. 112

- ^Warner, p. 147

- ^abBradford, p. 212

- ^Maffeo, p. 277

- ^Jordan, p. 219

- ^James, p. 186

- ^Gardiner, p. 67

- ^abMusteen, p. 20

- ^James, p. 265

- ^UKRetail Price Indexinflation figures are based on data fromClark, Gregory (2017)."The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)".MeasuringWorth.Retrieved7 May2024.

- ^abJames, p. 185

- ^abGardiner, p. 39

- ^abcJames, p. 187

- ^Warner, p. 146

- ^Lambert, Andrew(2007)."Nelson's Band of Brothers (act. 1798)".Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/96379.Archivedfrom the original on 12 November 2013.Retrieved21 October2009.(Subscription orUK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^"No. 20939".The London Gazette.26 January 1849. pp. 236–245.

- ^Gardiner, p. 40

- ^Adkins, p. 40

- ^Gardiner, p. 41

- ^Padfield, p. 135

- ^Germani, p. 56

- ^Germani, p. 63

- ^Mostert, p. 275

- ^Mostert, p. 706

- ^Germani, p. 67

- ^Herring, George C. (2008).From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776.New York: Oxford University Press. p. 88.ISBN978-0-19-972343-0.OCLC299054528.

- ^Cole, p. 108

- ^James, p. 179

- ^Maffeo, p. 272

- ^Clowes, p. 371

- ^Forester, p. 120

- ^Mostert, p. 274

- ^abPadfield, p. 132

- ^James, p. 189

- ^Gardiner, p. 70

- ^Rose, p. 144

- ^James, p. 294

- ^Gardiner, p. 62

- ^Chandler, p. 226

- ^Rodger, p. 461

- ^Gardiner, p. 14

- ^Maffeo, p. 275

- ^Gardiner, p. 78

- ^Ingram, p. 142

- ^Maffeo, p. 259

- ^Jordan & Rogers, p. 216

- ^Germani, p. 69

- ^Sweet, Nanora (2004)."Hemans, Felicia Dorothea".Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12888.Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2016.Retrieved21 October2009.(Subscription orUK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^Baker, p. 93

- ^Richard Savill (27 April 2009)."Battle of the Nile tree clumps pinpointed for visitors by National Trust".The Daily Telegraph.Archivedfrom the original on 20 December 2009.Retrieved20 October2009.

- ^Deutsch pp. 60–62