Beech

| Beech | |

|---|---|

| |

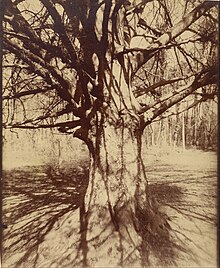

| European beech (Fagus sylvatica) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Subfamily: | Fagoideae K.Koch |

| Genus: | Fagus L. |

| Type species | |

| Castanea fagus | |

| Species | |

|

Seetext | |

Beech(Fagus) is agenusofdeciduoustreesin the familyFagaceae,native to temperateEurasiaandNorth America.There are 13 accepted species in two distinct subgenera,EnglerianaandFagus.The subgenusEnglerianais found only in East Asia, distinctive for its low branches, often made up of several major trunks with yellowish bark. The better knownFagussubgenus beeches are native to Europe and North America. They are high-branching trees with tall, stout trunks and smooth silver-grey bark. The European beechFagus sylvaticais the most commonly cultivated species, yielding a utility timber used for furniture construction, flooring and engineering purposes, in plywood, and household items. The timber can be used to build homes. Beechwood makes excellentfirewood.Slats of washed beech wood are spread around the bottom of fermentation tanks forBudweiserbeer. Beech logs are burned to dry themaltused in some Germansmoked beers.Beech is also used to smokeWestphalian ham,andouillesausage, and some cheeses.

Description[edit]

Beeches aremonoecious,bearing both male and female flowers on the same plant. The small flowers are unisexual, the female flowers borne in pairs, the male flowers wind-pollinatingcatkins.They are produced in spring shortly after the new leaves appear. The fruit of the beech tree, known as beechnuts or mast, is found in smallburrsthat drop from the tree in autumn. They are small, roughly triangular, and edible, with a bitter, astringent, or mild and nut-like taste.

The European beech (Fagus sylvatica) is the most commonly cultivated, although few important differences are seen between species aside from detail elements such asleafshape. The leaves of beech trees are entire or sparsely toothed, from 5–15 centimetres (2–6 inches) long and 4–10 cm (2–4 in) broad.

The bark is smooth and light gray. The fruit is a small, sharply three-anglednut10–15 mm (3⁄8–5⁄8in) long, borne singly or in pairs in soft-spined husks1.5–2.5 cm (5⁄8–1 in) long, known as cupules. The husk can have a variety of spine- to scale-like appendages, the character of which is, in addition to leaf shape, one of the primary ways beeches are differentiated.[1]The nuts have a bitter taste (though not nearly as bitter asacorns) and a hightannincontent; these are called beechnuts[2]or beech mast.

Taxonomy[edit]

Recent classification systems of the genus recognize 10 to 13 species in two distinct subgenera,EnglerianaandFagus.[3][1]TheEnglerianasubgenus is found only in East Asia, and is notably distinct from theFagussubgenus in that these beeches are low-branching trees, often made up of several major trunks with yellowish bark. Further differentiating characteristics include the whitish bloom on the underside of the leaves, the visible tertiary leaf veins, and a long, smooth cupule-peduncle. Proposed by botanist Chung-Fu Shen in 1992,F. japonica,F. engleriana,andF. okamotoicomprise this subgenus.[1]

The better knownFagussubgenus beeches are high-branching with tall, stout trunks and smooth silver-gray bark. This group includesF. sylvatica,F. grandifolia,F. crenata,F. lucida,F. longipetiolata,andF. hayatae.[1]The classification of the European beech,F. sylvatica,is complex, with a variety of different names proposed for different species and subspecies within this region (for exampleF. taurica,F. orientalis,andF. moesica[4]). Research suggests that beeches in Eurasia differentiated fairly late in evolutionary history, during theMiocene.The populations in this area represent a range of often overlapping morphotypes, and genetic analysis does not clearly support separate species.[5]

Fagusis the most basal group in the evolution of theFagaceaefamily, which also includesoaksandchestnuts.[6]Thesouthern beeches(genusNothofagus) previously thought closely related to beeches, are now treated as members of a separate family, theNothofagaceae(which remains a member of the orderFagales). They are found throughout the Southern Hemisphere inAustralia,New Zealand,New Guinea,New Caledonia,as well asArgentinaandChile(principallyPatagoniaandTierra del Fuego).

Species[edit]

Species accepted byPlants of the World Onlineas of April 2023[update]:[7]

| Image | Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Fagus chieniiW.C.Cheng | China (Sichuan) | |

|

Fagus crenataBlume– Siebold's beech or Japanese beech | Japan |

|

Fagus englerianaSeemenex Diels– Chinese beech | China |

|

Fagus grandifoliaEhrh.– American beech | Canada, United States, Mexico |

|

Fagus hayataePalib. ex Hayata | Taiwan |

|

Fagus japonicaMaxim. | Japan |

|

Fagus lucidaRehder &E.H.Wilson | China |

| Fagus multinervisNakai | South Korea (Ulleungdo) | |

|

Fagus orientalisLipsky– Oriental beech | Eastern Europe and Western Asia |

| Fagus pashanicaC.C.Yang | China (Sichuan, Zhejiang) | |

| Fagus sinensisOliv. | China (Hubei), Vietnam | |

|

Fagus sylvaticaL.– European beech | Europe |

Natural hybrids[edit]

| Image | Name | Parentage | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Fagus × tauricaPopl.– Crimean beech | F. orientalis×F. sylvatica | Eurasia |

Fossil species[edit]

Numerous species have been named globally from the fossil record spanning from theCretaceousto thePleistocene[8]

- †Fagus aburatoensisTanai, 1951[9]

- †Fagus alnitifoliaHollick[10]

- †Fagus altaensisKornilova & Rajushkina, 1979

- †Fagus ambigua(Massalongo) Massalongo, 1853

- †Fagus angustaAndreánszky, 1959

- †Fagus antipofiiHeer, 1858

- †Fagus apertaAndreánszky, 1959

- †Fagus arduinorumMassalongo, 1858

- †Fagus aspera(Berry) Brown, 1944

- †Fagus asperaChelebaeva, 2005(jr homonym)

- †Fagus atlanticaUnger, 1847

- †Fagus attenuataGöppert, 1855

- †Fagus aurelianiiMarion & Laurent, 1895

- †Fagus australisOliver, 1936

- †Fagus betulifoliaMassalongo, 1858

- †Fagus bonnevillensisChaney, 1920

- †Fagus castaneifoliaUnger, 1847

- †Fagus celastrifoliaEttingshausen, 1887

- †Fagus ceretana(Rérolle) Saporta, 1892

- †Fagus chamaephegosUnger, 1861

- †Fagus chankaicaAlexeenko, 1977

- †Fagus chiericiiMassalongo, 1858

- †Fagus chinensisLi, 1978

- †Fagus coalitaRylova, 1996

- †Fagus cordifoliaHeer, 1883

- †Fagus cretaceaNewberry, 1868

- †Fagus decurrensReid & Reid, 1915

- †Fagus dentataGöppert, 1855

- †Fagus deucalionisUnger, 1847

- †Fagus dubiaMirb, 1822

- †Fagus dubiaWatelet, 1866(jr homonym)

- †Fagus echinataChelebaeva, 2005

- †Fagus eocenicaWatelet, 1866

- †Fagus etheridgeiEttingshausen, 1891

- †Fagus ettingshauseniiVelenovský, 1881

- †Fagus europaeaSchwarewa, 1960

- †Fagus evenensisChelebaeva, 1980

- †Fagus faujasiiUnger, 1850

- †Fagus feroniaeUnger, 1845

- †Fagus floriniiHuzioka & Takahashi, 1973

- †Fagus forumliviiMassalongo, 1853

- †Fagus friedrichiiGrímsson & Denk, 2005

- †Fagus gortaniiFiori, 1940

- †Fagus grandifoliiformisPanova, 1966

- †Fagus gussoniiMassalongo, 1858

- †Fagus haidingeriKováts, 1856

- †Fagus herthae(Unger) Iljinskaja, 1964

- †Fagus hitchcockiiLesquereux, 1861

- †Fagus hondoensis(Watari) Watari, 1952

- †Fagus hookeriEttingshausen, 1887

- †Fagus horridaLudwig, 1858

- †Fagus humataMenge & Göppert, 1886

- †Fagus idahoensisChaney & Axelrod, 1959

- †Fagus inaequalisGöppert, 1855

- †Fagus incerta(Massalongo) Massalongo, 1858

- †Fagus integrifoliaDusén, 1899

- †Fagus intermediaNathorst, 1888

- †Fagus irvajamensisChelebaeva, 1980

- †Fagus japoniciformisAnanova, 1974

- †Fagus japonicoidesMiki, 1963

- †Fagus jobanensisSuzuki, 1961

- †Fagus jonesiiJohnston, 1892

- †Fagus juliaeJakubovskaya, 1975

- †Fagus kitamiensisTanai, 1995

- †Fagus koraicaHuzioka, 1951

- †Fagus kraeuseliiKvaček & Walther, 1991

- †Fagus kuprianoviaeRylova, 1996

- †Fagus lancifoliaHeer, 1868(nomen nudum)

- †Fagus langeviniiManchester & Dillhoff, 2004[11]

- †Fagus laptoneuraEttingshausen, 1895

- †Fagus latissimaAndreánszky, 1959

- †Fagus leptoneuronEttingshausen, 1893

- †Fagus macrophyllaUnger, 1854

- †Fagus maoricaOliver, 1936

- †Fagus marsilliiMassalongo, 1858

- †Fagus menzeliiKvaček & Walther, 1991

- †Fagus microcarpaMiki, 1933

- †Fagus miocenicaAnanova, 1974

- †Fagus napanensisIljinskaja, 1982

- †Fagus nelsonicaEttingshausen, 1887

- †Fagus oblongaSuzuki, 1959

- †Fagus oblongaAndreánszky, 1959

- †Fagus obscuraDusén, 1908

- †Fagus olejnikoviiPavlyutkin, 2015

- †Fagus orbiculatumLesquereux, 1892

- †Fagus orientaliformisKul'kova

- †Fagus orientalisvarfossilisKryshtofovich & Baikovskaja, 1951

- †Fagus orientalisvarpalibiniiIljinskaja, 1982

- †Fagus pacificaChaney, 1927

- †Fagus palaeococcusUnger, 1847

- †Fagus palaeocrenataOkutsu, 1955

- †Fagus palaeograndifoliaPavlyutkin, 2002

- †Fagus palaeojaponicaTanai & Onoe, 1961

- †Fagus pittmaniiDeane, 1902

- †Fagus pliocaenicaGeyler & Kinkelin, 1887(jr homonym)

- †Fagus pliocenicaSaporta, 1882

- †Fagus polycladusLesquereux, 1868

- †Fagus praelucidaLi, 1982

- †Fagus praeninnisianaEttingshausen, 1893

- †Fagus praeulmifoliaEttingshausen, 1893

- †Fagus priscaEttingshausen, 1867

- †Fagus pristinaSaporta, 1867

- †Fagus productaEttingshausen, 1887

- †Fagus protojaponicaSuzuki, 1959

- †Fagus protolongipetiolataHuzioka, 1951

- †Fagus protonuciferaDawson, 1884

- †Fagus pseudoferrugineaLesquereux, 1878

- †Fagus pygmaeaUnger, 1861

- †Fagus pyrrhaeUnger, 1854

- †Fagus salnikoviiFotjanova, 1988

- †Fagus sanctieugeniensisHollick, 1927

- †Fagus saxonicaKvaček & Walther, 1991

- †Fagus schofieldiiMindell, Stockey, & Beard, 2009

- †Fagus septembrisChelebaeva, 1991

- †Fagus shagianaEttingshausen, 1891

- †Fagus stuxbergiiTanai, 1976

- †Fagus subferrugineaWilfet al.,2005[12]

- †Fagus succineaGöppert & Menge, 1853

- †Fagus sylvaticavardiluvianaSaporta, 1892

- †Fagus sylvaticavarpliocenicaSaporta, 1873

- †Fagus tenellaPanova, 1966

- †Fagus uemuraeTanai, 1995

- †Fagus uotaniiHuzioka, 1951

- †Fagus vivianiiUnger, 1850

- †Fagus washoensisLaMotte, 1936

Fossil species formerly placed inFagusinclude:[8]

- †Alnus paucinervis(Borsuk) Iljinskaja

- †Castanea abnormalis(Fotjanova) Iljinskaja

- †Fagopsis longifolia(Lesquereux) Hollick

- †Fagopsis undulata(Knowlton) Wolfe & Wehr

- †Fagoxylon grandiporosum(Beyer) Süss

- †Fagus-pollenites parvifossilis(Traverse) Potonié

- †Juglans ginanniiMassalongo(new name forF. ginannii)

- †Nothofagaphyllites novae-zealandiae(Oliver) Campbell

- †Nothofagus benthamii(Ettingshausen) Paterson

- †Nothofagus dicksonii(Dusén) Tanai

- †Nothofagus lendenfeldii(Ettingshausen) Oliver

- †Nothofagus luehmannii(Deane) Paterson

- †Nothofagus magelhaenica(Ettingshausen) Dusén

- †Nothofagus maidenii(Deane) Chapman

- †Nothofagus muelleri(Ettingshausen) Paterson

- †Nothofagus ninnisiana(Unger) Oliver

- †Nothofagus risdoniana(Ettingshausen) Paterson

- †Nothofagus ulmifolia(Ettingshausen) Oliver

- †Nothofagus wilkinsonii(Ettingshausen) Paterson

- †Trigonobalanus minima(M. Chandler) Mai

Etymology[edit]

The name of the tree in Latin,fagus(from whence thegeneric epithet), is cognate with English "beech" and ofIndo-Europeanorigin, and played an important role in early debates on the geographical origins of theIndo-European people,thebeech argument.Greekφηγός (figós) is from the same root, but the word was transferred to the oak tree (e.g. Iliad 16.767) as a result of the absence of beech trees in southernGreece.[13]

Distribution and habitat[edit]

Britain and Ireland[edit]

Fagus sylvaticawas a late entrant toGreat Britainafter the last glaciation, and may have been restricted to basic soils in the south of England. Some suggest that it was introduced by Neolithic tribes who planted the trees for their edible nuts.[14]The beech is classified as a native in the south of England and as a non-native in the north where it is often removed from 'native' woods.[15]Large areas of theChilternsare covered with beech woods, which are habitat to thecommon bluebelland other flora. TheCwm Clydach National Nature Reservein southeast Wales was designated for its beech woodlands, which are believed to be on the western edge of their natural range in this steep limestone gorge.[16]

Beech is not native to Ireland; however, it was widely planted in the 18th century and can become a problem shading out the native woodland understory.

Beech is widely planted for hedging and in deciduous woodlands, and mature, regenerating stands occur throughout mainland Britain at elevations below about 650 m (2,100 ft).[17]The tallest and longest hedge in the world (according toGuinness World Records) is theMeikleour Beech HedgeinMeikleour,Perth and Kinross,Scotland.

Continental Europe[edit]

Fagus sylvaticais one of the most common hardwood trees in north-central Europe, in France constituting alone about 15% of all nonconifers. The Balkans are also home to the lesser-known oriental beech (F. orientalis) and Crimean beech (F. taurica).

As a naturally growing forest tree, beech marks the important border between the European deciduous forest zone and the northern pine forest zone. This border is important for wildlife and fauna.

In Denmark and Scania at the southernmost peak of the Scandinavian peninsula, southwest of the naturalspruceboundary, it is the most common forest tree. It grows naturally in Denmark and southern Norway and Sweden up to about 57–59°N. The most northern known naturally growing (not planted) beech trees are found in a small grove north ofBergenon the west coast of Norway. Near the city ofLarvikis the largest naturally occurring beech forest in Norway,Bøkeskogen.

Some research suggests that early agriculture patterns supported the spread of beech in continental Europe. Research has linked the establishment of beech stands in Scandinavia and Germany with cultivation and fire disturbance, i.e. early agricultural practices. Other areas which have a long history of cultivation, Bulgaria for example, do not exhibit this pattern, so how much human activity has influenced the spread of beech trees is as yet unclear.[18]

Theprimeval beech forests of the Carpathiansare also an example of a singular, complete, and comprehensive forest dominated by a single tree species - the beech tree. Forest dynamics here were allowed to proceed without interruption or interference since the last ice age. Nowadays, they are amongst the last pure beech forests in Europe to document the undisturbed postglacial repopulation of the species, which also includes the unbroken existence of typical animals and plants. These virgin beech forests and similar forests across 12 countries in continental Europe were inscribed on theUNESCO World Heritage Listin 2007.[19]

North America[edit]

The American beech (Fagus grandifolia) occurs across much of the eastern United States and southeastern Canada, with a disjunct population in Mexico. It is the onlyFagusspecies in the Western Hemisphere. Before thePleistoceneIce Age, it is believed to have spanned the entire width of the continent from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific but now is confined to the east of the Great Plains.F. grandifoliatolerates hotter climates than European species but is not planted much as an ornamental due to slower growth and less resistance to urban pollution. It most commonly occurs as an overstory component in the northern part of its range with sugar maple, transitioning to other forest types further south such as beech-magnolia. American beech is rarely encountered in developed areas except as a remnant of a forest that was cut down for land development.

The dead brown leaves of the American beech remain on the branches until well into the following spring, when the new buds finally push them off.

Asia[edit]

East Asia is home to five species ofFagus,only one of which (F. crenata) is occasionally planted in Western countries. Smaller thanF. sylvaticaandF. grandifolia,this beech is one of the most common hardwoods in its native range.

Ecology[edit]

Beech grows on a wide range of soil types, acidic or basic, provided they are not waterlogged. The tree canopy casts dense shade and thickens the ground withleaf litter.

In North America, they can formbeech-mapleclimaxforests by partnering with thesugar maple.

Thebeech blight aphid(Grylloprociphilus imbricator) is a common pest of American beech trees. Beeches are also used as food plants by some species ofLepidoptera.

Beech bark is extremely thin and scars easily. Since the beech tree has such delicate bark, carvings, such as lovers' initials and other forms of graffiti, remain because the tree is unable to heal itself.[20]

Diseases[edit]

Beech bark diseaseis a fungal infection that attacks the American beech through damage caused by scale insects.[21]Infection can lead to the death of the tree.[22]

Beech leaf diseaseis a disease that affects American beeches spread by the newly discovered nematode,Litylenchus crenatae mccannii.This disease was first discovered in Lake County, Ohio, in 2012 and has now spread to over 41 counties in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and Ontario, Canada.[23] As of 2024, the disease has become widespread in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and in portions of coastal New Hampshire and coastal and central Maine.[24]

Cultivation[edit]

The beech most commonly grown as anornamental treeis the European beech (Fagus sylvatica), widely cultivated in North America as well as its native Europe. Many varieties are in cultivation, notably the weeping beechF. sylvatica'Pendula', several varieties of copper or purple beech, the fern-leaved beechF. sylvatica'Asplenifolia', and the tricolour beechF. sylvatica'Roseomarginata'. The columnar Dawyck beech (F. sylvatica'Dawyck') occurs in green, gold, and purple forms, named afterDawyck Botanic Gardenin the Scottish Borders, one of the four garden sites of theRoyal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

Uses[edit]

Wood[edit]

Beech wood is an excellentfirewood,easily split and burning for many hours with bright but calm flames. Slats of beech wood are washed in caustic soda to leach out any flavour or aroma characteristics and are spread around the bottom of fermentation tanks forBudweiserbeer. This provides a complex surface on which the yeast can settle, so that it does not pile up, preventing yeastautolysiswhich would contribute off-flavours to the beer.[citation needed]Beech logs are burned to dry themaltused in Germansmoked beers.[25]Beech is also used to smokeWestphalian ham,[26]traditionalandouille(an offal sausage) from Normandy,[27]and some cheeses.

Somedrumsare made from beech, which has a tone between those ofmapleandbirch,the two most popular drum woods.

The textilemodalis a kind ofrayonoften made wholly from reconstitutedcelluloseof pulped beech wood.[28][29][30]

The European speciesFagus sylvaticayields a tough, utility timber. It weighs about 720 kg per cubic metre and is widely used for furniture construction, flooring, and engineering purposes, in plywood and household items, but rarely as a decorative wood. The timber can be used to build chalets, houses, and log cabins.[citation needed]

Beech wood is used for the stocks of military rifles when traditionally preferred woods such aswalnutare scarce or unavailable or as a lower-cost alternative.[31]

Food[edit]

The edible fruit of the beech tree,[2]known as beechnuts or mast, is found in small burrs that drop from the tree in autumn. They are small, roughly triangular, and edible, with a bitter, astringent, or in some cases, mild and nut-like taste. According to the Roman statesmanPliny the Elderin his workNatural History,beechnut was eaten by the people ofChioswhen the town was besieged, writing of the fruit: "that of the beech is the sweetest of all; so much so, that, according to Cornelius Alexander, the people of the city of Chios, when besieged, supported themselves wholly on mast".[32]They can also be roasted and pulverized into an adequatecoffee substitute.[33]The leaves can be steeped in liquor to give a light green/yellow liqueur.

Books[edit]

In antiquity, the bark of the beech tree was used byIndo-European peoplefor writing-related purposes, especially in a religious context.[34]Beech wood tablets were a commonwriting materialin Germanic societies before the development ofpaper.The Old Englishbōc[35]has the primary sense of "beech" but also a secondary sense of "book", and it is frombōcthat the modern word derives.[36]In modern German, the word for "book" isBuch,withBuchemeaning "beech tree". In modern Dutch, the word for "book" isboek,withbeukmeaning "beech tree". In Swedish, these words are the same,bokmeaning both "beech tree" and "book". There is a similar relationship in some Slavic languages. InRussianandBulgarian,the word for beech isбук(buk), while that for "letter" (as in a letter of the alphabet) is буква (bukva), whileSerbo-CroatianandSloveneuse "bukva"to refer to the tree.

Other[edit]

The pigmentbistrewas made from beech woodsoot.Beechlitterraking as a replacement for straw inanimal husbandrywas an old non-timber practice in forest management that once occurred in parts ofSwitzerlandin the 17th century.[37][38][39][40]Beech has been listed as one of the 38 plants whose flowers are used to prepareBach flower remedies.[41]

See also[edit]

- Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe

- English Lowlands beech forests

- The Weeping Beech

References[edit]

- ^abcdShen, Chung-Fu (1992).A Monograph of the GenusFagusTourn. Ex L. (Fagaceae)(PhD). City University of New York.OCLC28329966.

- ^abLyle, Katie Letcher (2010) [2004].The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants, Mushrooms, Fruits, and Nuts: How to Find, Identify, and Cook Them(2nd ed.). Guilford, CN:FalconGuides.p. 138.ISBN978-1-59921-887-8.OCLC560560606.

- ^Denk, Thomas; Grimm, Guido; Hemleben, Vera (2005)."Patterns of Molecular and Morphological Differentiation inFagus(Fagaceae): Phylogenetic Implications ".American Journal of Botany.92(6): 1006–16.doi:10.3732/ajb.92.6.1006.JSTOR4126078.PMID21652485.

- ^Gömöry, D.; Paule, L.; Brus, R.; Zhelev, P.; Tomović, Z.; Gračan, J. (1999)."Genetic differentiation and phylogeny of beech on the Balkan peninsula".Journal of Evolutionary Biology.12(4): 746–752.doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.1999.00076.x.S2CID83666988.

- ^Denk, Thomas; Grimm, Guido; Stogerer, K.; Langer, M.; Hemleben, Vera (2002). "The evolutionary history ofFagusin western Eurasia: Evidence from genes, morphology and the fossil record ".Plant Systematics and Evolution.232(3–4): 213–236.Bibcode:2002PSyEv.232..213D.doi:10.1007/s006060200044.JSTOR23644392.S2CID33581227.

- ^Manos, Paul S.; Steele, Kelly P. (1997)."Phylogenetic analysis of" Higher "Hamamelididae based on Plasid Sequence Data".American Journal of Botany.84(10): 1407–19.doi:10.2307/2446139.JSTOR2446139.PMID21708548.

- ^"Fagus L. - Plants of the World Online".Plants of the World Online.2022-05-07.Retrieved2023-04-24.

- ^ab"Fagus".The International Fossil Plant Names Index.Retrieved6 Feb2023.

- ^Tanai, T. "Des fossiles végétaux dans le bassin houiller de Nishitagawa, Préfecture de Yamagata, Japon".Japanese Journal of Geology and Geography.22:119–135.

- ^Brown, R. W. (1937).Additions to some fossil floras of the Western United States(PDF)(Report). Professional Paper. Vol. 186. United States Geological Survey. pp. 163–206.doi:10.3133/pp186J.

- ^Manchester, S. R.; Dillhoff, R. M. (2004). "Fagus(Fagaceae) fruits, foliage, and pollen from the Middle Eocene of Pacific Northwestern North America ".Canadian Journal of Botany.82(10): 1509–1517.doi:10.1139/b04-112.

- ^Wilf, P.; Johnson, K.R.; Cúneo, N.R.; Smith, M.E.; Singer, B.S.; Gandolfo, M.A. (2005)."Eocene Plant Diversity at Laguna del Hunco and Río Pichileufú, Patagonia, Argentina".The American Naturalist.165(6): 634–650.doi:10.1086/430055.PMID15937744.S2CID3209281.Retrieved2019-02-22.

- ^Robert Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Leiden and Boston 2010, pp. 1565–6

- ^"Map"(JPG).linnaeus.nrm.se.Retrieved2019-08-07.

- ^"International Foresters Study Lake District's greener, friendlier forests".Forestry Commission. Archived fromthe originalon 28 January 2010.Retrieved4 August2010.

- ^"Cwm Clydach".Countryside Council for Wales Landscape & wildlife. Archived fromthe originalon 25 September 2010.Retrieved4 August2010.

- ^Preston, C.D.; Pearman, D.; Dines, T.D. (2002).New Atlas of the British Flora.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-851067-3.

- ^Bradshaw, R.H.W.; Kito and, N.; Giesecke, T. (2010). "Factors influencing the Holocene history of Fagus".Forest Ecology and Management.259(11): 2204–12.doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2009.11.035.

- ^"Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe".UNESCO World Heritage Centre.United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization.Retrieved13 November2021.

- ^Lawrence, Gale; Tyrol, Adelaide (1984).A Field Guide to the Familiar: Learning to Observe the Natural World.Prentice-Hall. pp. 75–76.ISBN978-0-13-314071-2.

- ^"beech." The Columbia Encyclopedia. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008. Credo Reference. Web. 17 September 2012.

- ^"beech bark disease".Dictionary of Microbiology & Molecular Biology.Wiley. 2006.ISBN978-0-470-03545-0.Credo Reference. Web. 27 September 2012.

- ^Crowley, Brendan (2020-09-28)."Deadly 'Beech Leaf Disease' Identified Across Connecticut and Rhode Island".The Connecticut Examiner.Retrieved2020-11-15.

- ^University of New Hampshire

- ^"Der Brauprozeß von Schlenkerla Rauchbier".Schlenkerla - die historische Rauchbierbrauerei(in German). Schlenkerla. 2011.Retrieved11 December2020.

- ^"GermanFoods.org - Guide to German Sausages and German Hams".Archived fromthe originalon 2012-11-23.Retrieved2012-05-17.

- ^"What is andouille? | Cookthink".Archived fromthe originalon 2012-05-12.Retrieved2012-11-22.

- ^holistic-interior-designs.com,Modal FabricArchived2011-10-09 at theWayback Machine,retrieved 9 October 2011

- ^uniformreuse.co.uk,Modal data sheetArchived2011-10-24 at theWayback Machine,retrieved 9 October 2011

- ^fabricstockexchange.com,ModalArchived2011-09-25 at theWayback Machine(dictionary entry), retrieved 9 October 2011

- ^Walter, J. (2006).Rifles of the World(3rd ed.). Krause Publications.ISBN978-0-89689-241-5.

- ^"How did beech mast save the people of Chios? - Interesting Earth".interestingearth.com.Retrieved2019-10-07.

- ^United States Department of the Army(2009).The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants.New York:Skyhorse Publishing.p. 29.ISBN978-1-60239-692-0.OCLC277203364.

- ^Pronk-Tiethoff, Saskia (25 October 2013).The Germanic loanwords in Proto-Slavic.Rodopi. p. 81.ISBN978-94-012-0984-7.

- ^A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, Second Edition (1916),Blōtan-Boldwela,John Richard Clark Hall

- ^Douglas Harper."Book".Online Etymological Dictionary.Retrieved2011-11-18.

- ^Bürgi, M.; Gimmi, U. (2007)."Three objectives of historical ecology: the case of litter collecting in Central European forests"(PDF).Landscape Ecology.22(S1): 77–87.Bibcode:2007LaEco..22S..77B.doi:10.1007/s10980-007-9128-0.hdl:20.500.11850/58945.S2CID21130814.

- ^Gimmi, U.; Poulter, B.; Wolf, A.; Portner, H.; Weber, P.; Bürgi, M. (2013)."Soil carbon pools in Swiss forests show legacy effects from historic forest litter raking"(PDF).Landscape Ecology.28(5): 385–846.Bibcode:2013LaEco..28..835G.doi:10.1007/s10980-012-9778-4.hdl:20.500.11850/66782.S2CID16930894.

- ^McGrath, M.J.; et al. (2015)."Reconstructing European forest management from 1600 to 2010".Biogeosciences.12(14): 4291–4316.Bibcode:2015BGeo...12.4291M.doi:10.5194/bg-12-4291-2015.

- ^Scalenghe, R.; Minoja, A.P.; Zimmermann, S.; Bertini, S. (2016)."Consequence of litter removal on pedogenesis: A case study in Bachs and Irchel (Switzerland)".Geoderma.271:191–201.Bibcode:2016Geode.271..191S.doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.02.024.

- ^D. S. Vohra (1 June 2004).Bach Flower Remedies: A Comprehensive Study.B. Jain Publishers. p. 3.ISBN978-81-7021-271-3.Retrieved2 September2013.

External links[edit]

- "WCSP".World Checklist of Selected Plant Families – Fagus.

- Eichhorn, Markus (October 2010)."The Beech Tree".Test Tube.Brady Haranfor theUniversity of Nottingham.

- Traditional and Modern Use of Beech