Billy Nair

Billy Nair | |

|---|---|

| Member ofParliament of South Africa | |

| In office 1994–2004 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 November 1929 Durban,Natal Union of South Africa |

| Died | 23 October 2008(aged 78) Durban, South Africa |

| Political party | African National Congress |

| Other political affiliations | South African Communist Party |

Billy Nair(27 November 1929 – 23 October 2008) was a South African politician,trade unionist,andanti-apartheid activist.He was a member of theNational Assembly of South Africaand apolitical prisonerinRobben Island.

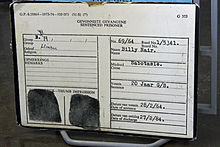

Nair was a long-serving political prisoner on Robben Island along withNelson Mandelain the 'B' Block for political prisoners. His prison card is the copy used in the post-reconciliation prison tours to illustrate the conditions of the prisoners of the time. He was elected to theAfrican National Congress(ANC) executive committee in 1991 and was a South African member of parliament for two terms prior to his retirement in 2004.

Early life

[edit]Nair was born in Sydenham,Durbanin the then province ofNatal,toIndianparents on 27 November 1929. His parents were Parvathy (daughter of a Passenger Indian) and Krishnan Nair (Ittynian Nair) who had been brought fromKerala,India as an indentured labourer. He was one of five children; his siblings were Joan, Angela, Jay and Shad. His youngest brother died oftyphoidin 1942. His father was an illiterate ship cargo man and mother supplemented the income by owning a vegetable stall in the Indian market.[1]

He attended school in Essendene Road Government Aided Indian School in Sydenham and Natal Technikon or M.L. Sultan Technical College (seeDurban University of Technology), Durban at night and completed hismatriculationin 1946 and diploma in accounting in 1949. During his school year, he also worked part-time as a shop assistant from 1946 - 48 for a timber merchant of Indian origin and as a bookkeeper for an accounting firm.

Early political activism

[edit]During his education days, he was politicized as a participant in the students union. Like many of his fellow leaders in the future, the "Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act",also known as the" Ghetto Act "galvanized his political beliefs. In 1949, he became a member of the Natal Indian Youth Congress and was elected as its secretary in 1950. He started attendingNatal Indian Congress(NIC) meetings becoming a member of its executive in 1950.[2]

Billy Nair continued his string of jobs and matriculation. After theNational Partygovernment came to power in 1948, the position of the authorities towards the protesters became very hostile. After six months stint as a dairy worker atCloverDairy earning 24 pounds a month, he was fired in 1950 as a result of histrade unionactivities.[2][3]As he explained in an interview in 1984 about this period, "We had to politicize workers. A means to establish a link between political struggle and the struggle for higher wages had to be found".[4]He continued his trade union activities, eventually becoming the full-time secretary of the Dairy Worker's Union in 1951. He was banned from political activities as part of the ban imposed in Natal of all that had served as secretaries of 16 trade unions under theSuppression of Communism Act.

Nair came under the influence ofDr. G. M. "Monty" Naicker,president of the Natal Indian Congress. In the resistance again the Ghetto act, no fewer than 2000 prisoners were arrested.[5]Nair was among the first group of resisters who were arrested at the Berea station with 21 other fellow-protesters for entering a "Europeans only" waiting room. He was imprisoned for one month.

Anti-apartheid activism

[edit]In 1953 Nair joined the secretly reconstitutedSouth African Communist partyand was a leading member of theSouth African Congress of Trade Unionswhen it was formed in 1955 and served on its national executive committee.[6]

Nair was among the 150 activists arrested with Mandela on 5 December 1956 and charged withtreason.The marathonTreason Trialof 1956–1961 followed. Two months into the trial, the initial indictment was dropped, and immediately a new indictment was issued against 30 people, all ANC members. He was acquitted of all charges.[7]Speaking of the incident, Nair later remarked, "The State wanted to actually bottle us up, thinking that the struggle will die out...".[8]

Umkhonto we Sizwe: 1961–1963

[edit]After the banning of ANC in 1960, Nair became a member of the underground organizationUmkhonto we Sizwe(MK) which was led by Mandela. Nair went underground for two months before being arrested and detained for 3 months. He was banned for 2 years which was subsequently extended to 5 years in 1961.[6]Between 1961 and 1963, he participated in the armed struggle as part of MK and was involved in the bombing of Indian Affairs Department.[9]

Robben Island: 1963–1984

[edit]On 6 July 1963, Nair was arrested and charged withsabotageand attempting to overthrow the government by violent means and sentenced to 20 years onRobben Islandalong with other members of the Natal Command of MK, includingCurnick Ndlovu,Ebrahim Ebrahim,Natoo Barberina, Riot Mkwanazi, Albert Duma,Eric Mtshaliand 12 others.[10][11]

Billy Nair, as Prisoner 69/64 (the 69th prisoner of 1964) served in the same block as Mandela andKathrada.

Billy Nair was assaulted multiple times in prison quite seriously and he joined multiple efforts including a five-day hunger strike to bring about reforms at the prison. In this, he partially succeeded. He was punished severely for his efforts by isolation and removal to the common block. He was also denied food and educational privileges for various periods of time. There was controversy on which groups were instrumental in making the changes in Robben Island, including the provision of beds of prisoners, permission to study and improved meals with various groups claiming credit. Upon release, he remarked on this, "when I came out of prison in 1984 I actually publicly said that these Coopers, theAZAPOS,theStrini Moodleysand the whole shoot of them actually came into a five star hotel. We changed the conditions so much that they were living in milk and honey virtually. "[1]

Whilst in prison, Nair was an active participant of the "University" which was informal education system run by prisoners;[12]he also obtained study privileges in time and completed B.A. (in English), and B.COM degrees through theUniversity of South Africa.Even though he completed most of the required classes toward a B.PROC degree, he had to abandon it after several detentions.Sonny Venkatrathnam,a fellow prisoner smuggled a copy ofShakespeareinto the prison in which all the leading prisoners marked their favorite passages; this copy was later called the Robben Island Bible. Billy Nair chose Caliban's lines fromThe Tempest:'This island's mine, by Sycorax my mother'.

United Democratic Front: 1984–1990

[edit]Nair was released from prison on 27 February 1984 and immediately joined theUnited Democratic Front(UDF), apopular frontagainst apartheid that had been established the year before.[13]He was elected to the national executive committee and regional executive committee of the UDF, became vice-chairperson of the Durban Central Residents' Association, and established the Centre for Community and Labour Studies, a labour-alignedthink-tank.[6]

Meanwhile, the UDF mounted a successful campaign to protest the1984 electionsto the newTricameral Parliament,provoking a stringent state response. Nair was arrested in August 1984 with several other UDF leaders, held under theInternal Security Act, 1982and accused of trying to "create a revolutionary climate".[14]After a judge ordered their release in early September, Nair and five others –Archie Gumede,Mewa Ramgobin,George Sewpershad,M. J. Naidoo, andPaul David– sought to avert their re-arrest by taking refuge in theBritish consulatein Durban.[15]As one of the so-calledDurban Six,Nair sheltered in the consulate between September and December 1984. At the end of the ordeal, he was the only one of the six who was not re-arrested and charged with treason in thePietermaritzburg Treason Trial.[16]

Although he escaped treason charges, Nair was detained again in late August 1985 and held under theInternal Security Act, 1982.[6]A month into hisdetention without trial,Nair successfully approached theNatal Supreme Courtwith an application to interdict the security police from assaulting him, alleging that he had been assaulted and harassed by two police officers.[17]He was ultimately released on 9 October 1985.[6]Thereafter, between June 1986 and February 1990, he went into hiding to evade further arrest, though he continued his activism underground.[6]Among other things he represented the SACP at its 1989 conference inHavana, Cuba,[6]and he also worked onOperation Vula.[18]

Transition: 1990–1994

[edit]Nair left hiding after the ANC and SACP were unbanned in February 1990 at an advanced stage of thenegotiations to end apartheid.However, on 23 July 1990, he and several other Operation Vula operatives were arrested in Durban.[19]During his subsequent detention, Nair suffered aheart attack,and he was released shortly after undergoingdouble bypass surgery.[6]After his release, he served on the interim leadership corps of both the ANC and the SACP, which were working to re-establish their legal structures inside South Africa.[20]In July 1990 he was elected to theSACP Central Committee,[20]and the ANC's48th National Conferencein December 1991 elected him to a three-year term as a member of theANC National Executive Committee.[21]

National Assembly and retirement

[edit]In thefirst post-apartheid electionsin April 1994, Nair stood as a candidate for the ANC, ranked 39th on the party's candidate list.[6]He was elected to a seat in theNational Assembly,the lower house of the newSouth African Parliament.Gaining re-election inJune 1999,he served two terms in his seat before retiring from Parliament at theApril 2004 general election.[6]He had dropped off the SACP Central Committee in 1998, but in his retirement he remained anex officiomember of the committee.[20]Asked during this period whether he had revised his view ofMarxism,Nair reflected:

[Marxism] remains relevant. But we cannot be dogmatic. We have to find a way out of capitalism as it is today. The world is not a better place today. Capitalism is a disaster for many people around the world. We will have to find our own approach to socialism... I am convinced that the future lies insocialism.The wealth of this country must belong to the people as a whole. Until that happens the struggle has to continue. There are no ready-made solutions to our problems. We have to be practical. We can't apply our theory in a vacuum. We have to engineer new methods to make it work. It is through the interaction of theory and practice that we will evolve new ways of solving problems. And over time we will find the answers to our challenges.[13]

He died on 23 October 2008 at St Augustine's Hospital in Durban, two weeks after suffering astroke.[22]S'bu Ndebele,thePremier of KwaZulu-Nataland Nair's former neighbour on Robben Island,[22]granted him an official provincial funeral,[23]which was held on 30 October 2008.[24]

Honours and awards

[edit]In 1988, the SACP awarded its inaugural Moses Kotane Award to Nair andBrian Buntingfor their outstanding contributions to the party.[6]He was admitted to theOrder of Luthuliin 2004, receiving the award in silver for "His contribution to the struggle for workers' rights and for anon-racialand non-sexist South Africa. "[25]In 2007, theGovernment of Indiaawarded him thePravasi Bharatiya Samman,[26]and the Gandhi Development Trust awarded him its Satyagraha Award.[6]Finally, in April 2009, he received a posthumous honorary doctorate from theUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal;Pravin Gordhanaccepted it on behalf of Nair's family.[27]

Personal life

[edit]In December 1960, Nair married Elsie Goldstone, a trade unionist who was his sister's next-door neighbour.[13]He had one daughter, who lived abroad.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abShongwe, Dimagatso (12 July 2002)."Voices of Resistance: Billy Nair".Documentation Centre Oral History Project.University of Durban–Westville.Retrieved31 May2009.

- ^ab"Oral Histories: Billy Nair interviewed by D. Shongwe".GANDHI-LUTHULI DOCUMENTATION CENTRE. 12 July 2002.Retrieved30 May2009.

- ^""We wish the adventurists luck" - Jacob Zuma ".politicsweb. 30 October 2008.Retrieved31 May2009.

- ^"Agent of the market, or instrument of justice? Redefining trade union identity in the era of market driven politics".Global Labor Institute. 18 September 2007.Retrieved30 May2009.

- ^Mandela, Nelson (1994).Long Walk to Freedom.London, United Kingdom.: Abacus Pub. p.118.ISBN978-0-349-10653-3.p.118

- ^abcdefghijklm"Billy Nair".South African History Online.1 December 2023.Retrieved24 June2024.

- ^"Defense Bulletin".National Library of South Africa. 1961.Retrieved30 May2009.

- ^"Audio interview with Billy Nair - Freedom Charter, Treason Trial [4:36]".

- ^"Oral Histories: Billy Nair interviewed by D. Shongwe".GANDHI-LUTHULI DOCUMENTATION CENTRE. 12 July 2002.Retrieved30 May2009.

- ^"Billy Nair: SA History Online".Retrieved25 June2013.

- ^South African Democracy Education Trust (2005).The Road to Democracy in South Africa 1960-1970.Struik. p. 251.

- ^Mandela, Nelson (1994).Long Walk to Freedom.London, United Kingdom.: Abacus Pub. p.556.ISBN978-0-349-10653-3.

- ^abc"A working-class hero".The Witness.29 October 2008.Retrieved25 June2024.

- ^Riveles, Susanne (1989)."Diplomatic Asylum as a Human Right: The Case of the Durban Six".Human Rights Quarterly.11(1): 139–159.doi:10.2307/761937.ISSN0275-0392.JSTOR761937.

- ^Cowell, Alan(14 September 1984)."6 South African fugitives enter British consulate".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Retrieved29 April2023.

- ^"Repressing the UDF Leadership".South African History Archive.2013.Retrieved29 April2023.

- ^"A Supreme Court judge in Durban ordered police today..."UPI.30 September 1985.Retrieved2 July2023.

- ^Thamm, Marianne (19 February 2020)."A Nightingale Sang in CR Swart Square: Moe Shaik and the greatest story not yet told".Daily Maverick.Retrieved26 December2021.

- ^"Vula Eight: Charge Sheet".O'Malley Archives.Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2021.Retrieved26 December2021.

- ^abc"Hamba Kahle Comrade Billy Nair".Pragoti.30 October 2008. Archived fromthe originalon 6 December 2008.Retrieved30 May2009.

- ^"Report of the Independent Electoral Commission".African National Congress.6 July 1991.Retrieved17 November2022.

- ^ab"ANC salutes 'gallant revolutionary' Billy Nair".The Mail & Guardian.23 October 2008.Retrieved25 June2024.

- ^"Billy Nair: Official provincial funeral".The Witness.25 October 2008.Retrieved25 June2024.

- ^"Scores gather for Nair's funeral".News24.30 October 2008.Retrieved25 June2024.

- ^"Billy Nair (1929–)".Presidency of the Republic of South Africa.Retrieved24 June2024.

- ^"Pravasi Bharatiya Samman Award (2003 to 2021): List of Recipients".Pravasi Bhartiya Divas.Retrieved25 June2024.

- ^"Graduation Highlights 2009".University of KwaZulu-Natal.18 April 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 21 May 2009.Retrieved30 May2009.

External links

[edit]- InterviewswithPadraig O'Malley(2002–2004)

- South African anti-apartheid activists

- South African politicians of Indian descent

- Malayali people

- 1929 births

- 2008 deaths

- People acquitted of treason

- South African prisoners and detainees

- Inmates of Robben Island

- Natal Indian Congress politicians

- African National Congress politicians

- South African Communist Party politicians

- Members of the National Assembly of South Africa

- Durban University of Technology alumni

- Members of the Order of Luthuli

- Apartheid in South Africa

- Politicians from Durban

- Racial segregation

- Recipients of Pravasi Bharatiya Samman