Biwa

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(December 2020) |

A selection ofbiwain a Japanese museum | |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| Related instruments | |

| |

Thebiwa(Japanese:Tỳ bà)is a Japanese short-necked woodenlutetraditionally used in narrative storytelling. Thebiwais a plucked string instrument that first gained popularity inChinabefore spreading throughoutEast Asia,eventually reaching Japan sometime during theNara period(710–794). Typically 60 centimetres (24 in) to 106 centimetres (42 in) in length, the instrument is constructed of a water drop-shaped body with a short neck, typically with four (though sometimes five) strings. In Japan, thebiwais generally played with abachiinstead of the fingers, and is often used to playgagaku.One of thebiwa's most famous uses is for recitingThe Tale of theHeike,a war chronicle from theKamakura period(1185–1333). In previous centuries, the predominantbiwamusicians would have been blind monks(Tỳ bà pháp sư,biwa hōshi),who used thebiwaas musical accompaniment when reading scriptural texts.

Thebiwa's Chinese predecessor was thepipa(Tỳ bà), which arrived in Japan in two forms;[further explanation needed]following its introduction to Japan, varieties of thebiwaquadrupled. Guilds supportingbiwaplayers, particularly thebiwa hōshi,helped proliferatebiwamusical development for hundreds of years.Biwa hōshiperformances overlapped with performances by otherbiwaplayers many years beforeheikyoku(Bình khúc,The Tale of theHeike),[further explanation needed]and continues to this day. This overlap resulted in a rapid evolution of thebiwaand its usage and made it one of the most popular instruments in Japan.

In spite of its popularity, theŌnin Warand subsequentWarring States Perioddisruptedbiwateaching and decreased the number of proficient users. With the abolition ofTodoin theMeiji period,biwaplayers lost their patronage.

By the late 1940s, thebiwa,a thoroughly Japanese tradition, was nearly completely abandoned for Western instruments; however, thanks to collaborative efforts by Japanese musicians, interest in thebiwais being revived. Japanese and foreign musicians alike have begun embracing traditional Japanese instruments, particularly thebiwa,in their compositions. While blindbiwasingers no longer dominate thebiwa,many performers continue to use the instrument in traditional and modern ways.

History[edit]

Thebiwaarrived in Japan in the 7th century, having evolved from the Chinese bent-neckpipa(Khúc hạng tỳ bà;quxiang pipa),[1]while thepipaitself was derived from similar instruments inWest Asia.This type ofbiwa,known as thegaku-biwa,was later used ingagakuensembles and became the most commonly known type. However, another variant of thebiwa– known as themōsō-biwaor thekōjin-biwa– also found its way to Japan, first appearing in theKyushuregion. Though its origins are unclear, this thinner variant of thebiwawas used in ceremonies and religious rites.

Thebiwabecame known as an instrument commonly played at the Japanese Imperial court, wherebiwaplayers, known asbiwa hōshi,found employment and patronage. However, following the collapse of theRitsuryōstate,biwa hōshiemployed at the court were faced with the court's reconstruction and sought asylum inBuddhisttemples. There, they assumed the role of Buddhist monks and encountered themōsō-biwa.Seeing its relative convenience and portability, the monks combined these features with their large and heavygaku-biwato create theheike-biwa,which, as indicated by its namesake, was used primarily for recitations ofThe Tale of theHeike.

Through the next several centuries, players of both traditions intersected frequently and developed new music styles and new instruments. By theKamakura period(1185–1333), theheike-biwahad emerged as a more popular instrument, a cross between both thegaku-biwaandmōsō-biwa,retaining the rounded shape of thegaku-biwaand played with a largeplectrumlike themōsō-biwa.Theheike-biwa,smaller than themōsō-biwa,was used for similar purposes.

While the modernsatsuma-biwaandchikuzen-biwaboth originated from themōsō-biwa,thesatsuma-biwawas used for moral and mental training bysamuraiof theSatsuma Domainduring theWarring States period,and later for general performances. Thechikuzen-biwawas used by Buddhist monks visiting private residences to perform memorial services, not only for Buddhist rites, but also to accompany the telling of stories and news.

Though formerly popular, little was written about the performance and practice of thebiwafrom roughly the 16th century to the mid-19th century. What is known is that three main streams ofbiwapractice emerged during this time:zato(the lowest level of the state-controlled guild of blindbiwaplayers),shifu(samurai style), andchofu(urban style). These styles emphasizedbiwa-uta(Tỳ bà ca)– vocalisation withbiwaaccompaniment – and formed the foundation foredo-uta(Giang hộ ca)styles of playing, such asshinnaiandkota.[2]

From these styles also emerged the two principal survivors of thebiwatradition:satsuma-biwaandchikuzen-biwa.[3]From roughly theMeiji period(1868–1912) until thePacific War,thesatsuma-biwaandchikuzen-biwawere popular across Japan, and, at the beginning of theShōwa period(1925–1989), thenishiki-biwawas created and gained popularity. Of the remaining post-warbiwatraditions, onlyhigo-biwaremains a style almost solely performed by blind persons. Thehigo-biwais closely related to theheike-biwaand, similarly, relies on an oral narrative tradition focusing on wars and legends.

By the middle of the Meiji period, improvements had been made to the instruments and easily understandable songs were composed in quantity. In the beginning of theTaishō period(1912–1926), thesatsuma-biwawas modified into thenishiki-biwa,which became popular among female players at the time. With this, thebiwaentered a period of popularity, with songs reflecting not justThe Tale of theHeike,but also theSino-Japanese Warand theRusso-Japanese War,with songs such asTakeo Hirose,HitachimaruandHill 203gaining popularity.

However, the playing of thebiwanearly became extinct during the Meiji period following the introduction of Western music and instruments, until players such asTsuruta Kinshiand others revitalized the genre with modern playing styles and collaborations with Western composers.[citation needed]

Types[edit]

There are more than seven types ofbiwa,characterised by number of strings, sounds it could produce, the type ofplectrum,and their use. As thebiwadoes not play intemperedtuning, pitches are approximated to the nearest note.

Classicbiwa[edit]

Gagaku-biwa[edit]

Thegagaku biwa(Nhã lặc tỳ bà),a large and heavybiwawith four strings and four frets, is used exclusively forgagaku.It produces distinctiveichikotsuchō(Nhất việt điều)andhyōjō(Bình điều).Its plectrum is small and thin, often rounded, and made from a hard material such asboxwoodorivory.It is not used to accompany singing. Like theheike-biwa,it is played held on its side, similar to a guitar, with the player sitting cross-legged. Ingagaku,it is known as thegaku-biwa(Lặc tỳ bà).

Gogen-biwa[edit]

Thegogen-biwa(Ngũ huyền tỳ bà,lit. 'five-stringedbiwa'),aTangvariant ofbiwa,can be seen in paintings of court orchestras and was used in the context ofgagaku;however, it was removed with the reforms and standardization made to the court orchestra during the late 10th century. It is assumed that the performance traditions died out by the 10th or 11th century (William P. Malm). This instrument also disappeared in the Chinese court orchestras. Recently, this instrument, much like thekonghouharp, has been revived for historically informed performances and historical reconstructions. Not to be confused with the five-stringed variants of modernbiwa,such aschikuzen-biwa.

Mōso-biwa[edit]

Themōsō-biwa(Manh tăng tỳ bà),abiwawith four strings, is used to play Buddhistmantrasand songs. It is similar in shape to thechikuzen-biwa,but with a much more narrow body. Its plectrum varies in both size and materials. The four fret type is tuned to E, B, E and A, and the five fret type is tuned to B, e, f♯and f♯.The six fret type is tuned to B♭,E♭,B♭and b♭.

Middle and Edobiwa[edit]

Heike-biwa[edit]

Theheike-biwa(Bình gia tỳ bà),abiwawith four strings and five frets, is used to playThe Tale of theHeike.Its plectrum is slightly larger than that of thegagaku-biwa,but the instrument itself is much smaller, comparable to achikuzen-biwain size. It was originally used by travelingbiwaminstrels, and its small size lent it to indoor play and improved portability. Its tuning is A, c, e, a or A, c-sharp, e, a.

Satsuma-biwa[edit]

Thesatsuma-biwa(Tát ma tỳ bà),abiwawith four strings and four frets, was popularized during the Edo period inSatsuma Province(present-dayKagoshima) byShimazu Tadayoshi.Modernbiwaused for contemporary compositions often have five or more frets, and some have a doubled fourth string. The frets of thesatsuma-biwaare raised 4 centimetres (1.6 in) from the neck allowing notes to be bent several steps higher, each one producing the instrument's characteristicsawari,or buzzing drone. Its boxwood plectrum is much wider than others, often reaching widths of 25 cm (9.8 in) or more. Its size and construction influences the sound of the instrument as the curved body is often struck percussively with the plectrum during play.

Thesatsuma-biwais traditionally made fromJapanese mulberry,although other hard woods such asJapanese zelkovaare sometimes used in its construction. Due to the slow growth of the Japanese mulberry, the wood must be taken from a tree at least 120 years old and dried for 10 years before construction can begin.

The strings are made of wound silk. Its tuning is A, E, A, B, for traditionalbiwa,G, G, c, g, or G, G, d, g for contemporary compositions, among other tunings, but these are only examples as the instrument is tuned to match the key of the player's voice. The first and second strings are generally tuned to the same note, with the 4th (or doubled 4th) string is tuned one octave higher.

The most eminent 20th centurysatsuma-biwaperformer wasTsuruta Kinshi,who developed her own version of the instrument, which she called thetsuruta-biwa.Thisbiwaoften has five strings (although it is essentially a 4-string instrument as the 5th string is a doubled 4th that are always played together) and five or more frets, and the construction of the tuning head and frets vary slightly.Ueda JunkoandTanaka Yukio,two of Tsuruta's students, continue the tradition of the modernsatsuma-biwa.Carlo Forlivesi's compositionsBoethius(ボエティウス) andNuove Musiche per Biwa(Tỳ bà のための tân khúc) were both written for performance on thesatsuma-biwadesigned by Tsuruta and Tanaka.

These works present a radical departure from the compositional languages usually employed for such an instrument. Also, thanks to the possibility of relying on a level of virtuosity never before attempted in this specific repertory, the composer has sought the renewal of the acoustic and aesthetic profile of thebiwa,bringing out the huge potential in the sound material: attacks and resonance, tempo (conceived not only in the chronometrical but also deliberately empathetical sense), chords, balance and dialogue (with the occasional use of twobiwas inNuove Musiche per Biwa), dynamics and colour.[4]

Modernbiwa[edit]

Chikuzen-biwa[edit]

TheChikuzen-biwa(Trúc tiềnTỳ bà),abiwawith four strings and four frets or five strings and five frets, was popularised in the Meiji period by Tachibana Satosada. Most contemporary performers use the five string version. Its plectrum is much smaller than that of thesatsuma-biwa,usually about 13 cm (5.1 in) in width, although its size, shape, and weight depends on the sex of the player. The plectrum is usually made fromrosewoodwith boxwood or ivory tips for plucking the strings. The instrument itself also varies in size, depending on the player. Male players typically playbiwathat are slightly wider and/or longer than those used by women or children. The body of the instrument is never struck with the plectrum during play, and the five string instrument is played upright, while the four string is played held on its side. The instrument is tuned to match the key of the singer. An example tuning of the four string version is B, e, f♯and b, and the five string instrument can be tuned to C, G, C, d and g. For the five string version, the first and third strings are tuned the same note, the second string three steps down, the fifth string an octave higher than the second string, and the fourth string a step down from the fifth. So the previously mentioned tuning can be tuned down to B♭,F, B♭,c, d. Asahikai and Tachibanakai are the two major schools ofchikuzen-biwa.Popularly used by femalebiwaplayers such asUehara Mari.

Nishiki-biwa[edit]

Thenishiki-biwa(Cẩm tỳ bà),a modernbiwawith five strings and five frets, was popularised by the 20th-centurybiwaplayer and composer Suitō Kinjō(Thủy đằng cẩm nhương,1911–1973).Its plectrum is the same as that used for thesatsuma-biwa.Its tuning is C, G, c, g, g.

-

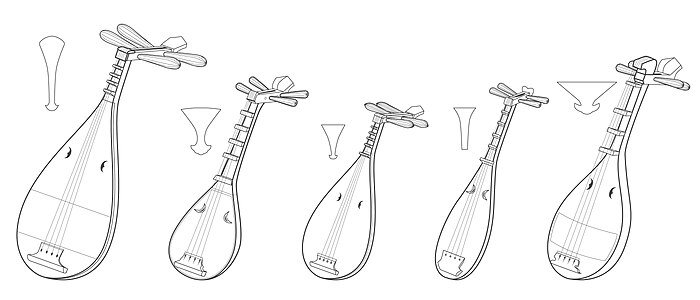

Gaku-biwa, chikuzen-biwa, heike-biwa, mōsō-biwa, satsuma-biwaand their plectra

Styles ofbiwamusic[edit]

Thebiwa,considered one of Japan's principal traditional instruments, has both influenced and been influenced by other traditional instruments and compositions throughout its long history; as such, a number of different musical styles played with thebiwaexist.

- Hōgaku(Bang lặc,Japanese traditional music):Inhōgaku,musical instruments usually serve as accompaniments to vocal performances, which dominate the musical style, with the overwhelming majority ofhōgakucompositions being vocal.[5]

- Gagaku(Nhã lặc,Japanese court music):Gagakuwas usually patronized by the imperial court or the shrines and temples.Gagakuensembles were composed of string, wind, and percussion instruments, where string and wind instruments were more respected and percussion instruments were considered lesser instruments. Among the string instruments, thebiwaseems to have been the most important instrument in orchestralgagakuperformances.[6]

- Shōmyō(Thanh minh,Buddhist chanting):Whilebiwawas not used inshōmyō,the style ofbiwasinging is closely tied toshōmyō,especiallymōsō-andheike-stylebiwasinging.[7]Bothshōmyōandmōsō-biwaare rooted in Buddhist rituals and traditions. Before arriving in Japan,shōmyōwas used in Indian Buddhism. Themōsō-biwawas also rooted inIndian Buddhism,and theheike-biwa,as a predecessor to themōsō-biwa,was the principal instrument of thebiwa hōshi,who were blind Buddhist priests.

Biwaconstruction and tuning[edit]

Generally speaking,biwahave four strings, though modernsatsuma-andchikuzen-biwamay have five strings. The strings on abiwarange in thickness, with the first string being thickest and the fourth string being thinnest; onchikuzen-biwa,the second string is the thickest, with the fourth and fifth strings being the same thickness onchikuzen-andsatsuma-biwa.[8]The varying string thickness creates differenttimbreswhen stroked from different directions.

Inbiwa,tuningis not fixed. Generaltonesandpitchescan fluctuate up or down entire steps ormicrotones.[9]When singing in a chorus,biwasingers often stagger their entry and often sing through non-synchronized,heterophonyaccompaniment.[10]In solo performances, abiwaperformer singsmonophonically,withmelismaticemphasis throughout the performance. These monophonic do not follow a set harmony. Instead,biwasingers tend to sing with a flexible pitch without distinguishingsoprano,alto,tenor,orbassroles. This singing style is complemented by thebiwa,whichbiwaplayers use to produce short glissandi throughout the performance.[11]The style of singing accompanyingbiwatends to be nasal, particularly when singing vowels, the consonantん,and syllables beginning with "g", such asga(が)andgi(ぎ).Biwaperformers also vary the volume of their voice between barely audible to very loud. Sincebiwapieces were generally performed for small groups, singers did not need to project their voices asoperasingers did in Western music tradition.

Biwamusic is based on apentatonic scale(sometimes referred to as a five-tone or five-note scale), meaning that eachoctavecontains five notes. This scale sometimes includes supplementary notes, but the core remainspentatonic.The rhythm inbiwaperformances allows for a broad flexibility of pulse. Songs are not always metered, although more modern collaborations are metered. Notes played on thebiwausually begin slow and thin and progress through gradual accelerations, increasing and decreasing tempo throughout the performance. The texture ofbiwasinging is often described as "sparse".

Theplectrumalso contributes to the texture ofbiwamusic. Different sized plectrums produced different textures; for example, the plectrum used on amōsō-biwawas much larger than that used on agaku-biwa,producing a harsher, more vigorous sound.[12]The plectrum is also critical to creating thesawarisound, which is particularly utilized withsatsuma-biwa.[13]What the plectrum is made of also changes the texture, with ivory and plastic plectrums creating a more resilient texture to the wooden plectrum's twangy hum.[14]

Use in modern music[edit]

Biwausage in Japan has declined greatly since theHeian period.Outside influence, internal pressures, and socio-political turmoil redefinedbiwapatronage and the image of thebiwa;for example, theŌnin Warof theMuromachi period(1338–1573) and the subsequentWarring States period(15th–17th centuries) disrupted the cycle of tutelage forheikyoku[citation needed][a]performers. As a result, younger musicians turned to other instruments and interest inbiwamusic decreased. Even thebiwa hōshitransitioned to other instruments such as theshamisen(a three-stringed lute).[15]

Interest in thebiwawas revived during theEdo period(1600–1868), whenTokugawa Ieyasuunified Japan and established theTokugawa shogunate.Ieyasu favoredbiwamusic and became a major patron, helping to strengthenbiwaguilds (calledTodo) by financing them and allowing them special privileges.Shamisenplayers and other musicians found it financially beneficial to switch to thebiwa,bringing new styles ofbiwamusic with them. The Edo period proved to be one of the most prolific and artistically creative periods for thebiwain its long history in Japan.

In 1868, the Tokugawa shogunate collapsed, giving way to theMeiji periodand theMeiji Restoration,during which thesamuraiclass was abolished, and theTodolost their patronage.Biwaplayers no longer enjoyed special privileges and were forced to support themselves. At the beginning of the Meiji period, it was estimated that there were at least one hundred traditional court musicians in Tokyo; however, by the 1930s, this number had reduced to just 46 in Tokyo, and a quarter of these musicians later died inWorld War II.Life inpost-war Japanwas difficult, and many musicians abandoned their music in favor of more sustainable livelihoods.[16]

While many styles ofbiwaflourished in the early 1900s (such askindai-biwabetween 1900 and the 1930s), the cycle of tutelage was broken yet again by the war. In the present day, there are no direct means of studying thebiwain manybiwatraditions.[17]Evenhigo-biwaplayers, who were quite popular in the early 20th century, may no longer have a direct means of studying oral composition, as the bearers of the tradition have either died or are no longer able to play.Kindai-biwastill retains a significant number of professional and amateur practitioners, but thezato,heike,andmoso-biwastyles have all but died out.[18]

Asbiwamusic declined in post-Pacific WarJapan, many Japanese composers and musicians found ways to revitalize interest in it. They recognized that studies inmusic theoryandmusic compositionin Japan almost entirely consisted in Western theory and instruction. Beginning in the late 1960s, these musicians and composers began to incorporate Japanese music and Japanese instruments into their compositions; for example, one composer,Tōru Takemitsu,collaborated with Western composers and compositions to include the distinctly Asianbiwa.His well-received compositions, such asNovember Steps,which incorporatedbiwa heikyokuwith Western orchestral performance, revitalized interest in thebiwaand sparked a series of collaborative efforts by other musician in genres ranging fromJ-Popandenkatoshin-hougakuandgendaigaku.[19]

Other musicians, such as Yamashika Yoshiyuki, considered by most ethnomusicologists to be the last of thebiwa hōshi,preserved scores of songs that were almost lost forever. Yamashika, born in the late Meiji period, continued thebiwa hōshitradition until his death in 1996. Beginning in the late 1960s to the late 1980s, composers and historians from all over the world visited Yamashika and recorded many of his songs; before this time, thebiwa hōshitradition had been a completely oral tradition. When Yamashika died in 1996, the era of thebiwa hōshitutelage died with him, but the music and genius of that era continues thanks to his recordings.[20]

Recordings[edit]

- Silenziosa Luna–Thẩm mặc の nguyệt/ ALM Records ALCD-76 (2008).

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Heikyokuis one of the oldest Japanese traditional music genres, originating in the 13th century. It is a semi-classical bardic tradition, not unlike the troubadour music of medieval Europe.

References[edit]

- ^"Biwa | musical instrument".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved21 April2021.

- ^Allan Marett 103

- ^Waterhouse 15

- ^ALM Records ALCD-76

- ^Dean 156

- ^Garfias, Gradual Modifications of the Gagaku Tradition 16

- ^Matisoff 36

- ^Minoru Miki 75

- ^Dean 157

- ^Dean 149

- ^Morton Feldman 181

- ^Morley 51

- ^Rossing 181

- ^Malm 21

- ^Gish 143

- ^Garfias, Gradual Modifications of the Gagaku Tradition 18

- ^Ferranti, Relations between Music and Text in "Higo Biwa", The "Nagashi" Pattern as a Text-MusicSystem 150

- ^Tokita 83

- ^Tonai 25

- ^Sanger