Blackheath, London

| Blackheath | |

|---|---|

All Saints' Church,designed byBenjamin Ferrey,dates from 1857 | |

Location withinGreater London | |

| Population | 26,914 (2011 Census. Lewisham Ward: 14,039)[1](2011 Census. Blackheath Westcombe Ward: 12,875)[2] |

| OS grid reference | TQ395765 |

| •Charing Cross | 6.4 mi (10.3 km)WNW |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | SE3, SE12, SE13 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Blackheathis an area in Southeast London, straddling the border of theRoyal Borough of Greenwichand theLondon Borough of Lewisham.[3]Historically within the county ofKent,it is located 1-mile (1.6 km) northeast ofLewisham,1.5 miles (2.4 km) south ofGreenwichand 6.4 miles (10.3 km) southeast ofCharing Cross,the traditional centre of London.

The area southwest of its station and in itswardis named Lee Park. Its northern neighbourhood of Vanbrugh Park is also known as St John's Blackheath and despite forming a projection has amenities beyond its traditional reach named after the heath. To its west is the core public green area that is the heath andGreenwich Park,in which sit major London tourist attractions including theGreenwich Observatoryand theGreenwich Prime Meridian.Blackheath railway stationis south of the heath.

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]- Records and meanings

The name is fromOld Englishspoken words 'blæc' and 'hǣth'. The name is recorded in 1166 asBlachehedfeldwhich means "dark,[4]or black heath field "– field denotes an enclosure or clearing.Lewis's topological dictionary opines, considering the adjective developed equally into derived term bleak, that Blackheath "takes its name either from the colour of the soil, or from the bleakness of its situation" before adding, reflecting Victorian appreciation, mention of "numerousvillaswith which it now abounds...it is pleasantly situated on elevated ground, commanding diversified and extensive views of the surrounding country, which is richly cultivated, and abounds with fine scenery ".[5]It was an upland, open space that was the meeting place of thehundredofBlackheath.[4]

- Formal name for estates around the heath

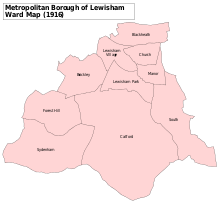

By 1848 Blackheath was noted as a place with twodependent chapelsunder Lewishamvestryand another,St Michael and All Angels,erected 1828-1830 designed byGeorge Smith.The latter made use of £4000 plus land from land developerJohn Cator,[6]plus a further £11,000 from elsewhere.[5]The name of Blackheath gained independent official boundaries by the founding of an Anglican parish in 1854, then others (in 1859, 1883 and 1886) which reflected considerable housing built on nearby land.[7][8][9][10]In local government, Blackheath never saw independence;[11][12]at first split between the Lewisham, Lee, Charlton and Greenwich vestries or civil parish councils and Kidbrooke liberty,[13]which assembled intoGreenwich,Plumstead (in final years called Lee)andLewisham Districtsthen re-assembled with others into Greenwich and Lewishammetropolitan boroughsin 1900.[11]

- Etymological myth

Anurban mythis Blackheath could derive from the1665 Plagueor theBlack Deathof the mid-14th century. A local burial pit is nonetheless likely during the Black Death, given the established village and safe harbour (hithe) status ofGreenwich.At those times the high death rate meant that a guaranteed churchyard burial became impractical.

Archaeology

[edit]A keyCeltic trackway(becoming aRoman roadand laterWatling Street) scaled the rise that is shared withGreenwich Parkand a peak 1 mile (1.6 km)east-by-southeast,Shooters Hill.In the west this traversed the mouth ofDeptford Creek(theRiver Ravensbourne) (a corruption or throwback to earlier pronunciation of deep ford).[14][15]Other finds can be linked to passing trade connected with royal palaces. In 1710, several Roman urns were dug up, two of which were of fine red clay, one of a spherical, and the other of a cylindrical, form; and in 1803, several more were discovered in the gardens of theEarl of Dartmouthand given to theBritish Museum.[5]

Royal setting

[edit]

Certain monarchs passed through and their senior courtiers kept residences here and in Greenwich. Before theTudor-builtGreenwich Palaceand Stuart-builtQueen's House,one of the most frequently used wasEltham Palaceabout 2.5 miles (4.0 km) to the southeast of the ridge, under the latePlantagenets,before cessation as aroyal residencein the 16th century.

On the north side of the heath,Ranger's House,a medium-sized red brick Georgian mansion in thePalladianstyle, backs directly onto Greenwich Park. Associated with the Ranger of Greenwich Park, a royal appointment, the house was the Ranger's official residence for most of the 19th century (neighbouringMontagu House,demolished in 1815, was a royal residence ofCaroline of Brunswick). Since 2002, Ranger's House has housed theWernher Collectionof art.

The Pagoda is a notably exquisite home, built in 1760 by SirWilliam Chambersin the style of a traditional Chinese pagoda. It was later leased to thePrince Regent,principally used as a summer home by Caroline of Brunswick.

Meeting point

[edit]

Blackheath was a rallying point forWat Tyler'sPeasants' Revoltof 1381,[16]and forJack Cade's Kentish rebellion in 1450 (both recalled by road names on the west side of the heath). After camping at Blackheath,Cornishrebels were defeated at the foot of the west slope in theBattle of Deptford Bridge(sometimes called the Battle of Blackheath) on 17 June 1497.

In 1400,Henry IV of Englandmet here with Byzantine EmperorManuel II Palaiologoswho toured western royalty to seek support to opposeBayezid I (Bajazet),the Ottoman Sultan. In 1415, the lord mayor and aldermen of London, in their robes of state, attended by 400 of the principal citizens, clothed in scarlet, came hither in procession to meetHenry V of Englandon his triumphant return from theBattle of Agincourt.[5]

Blackheath was, along withHounslow Heath,a common assembly point for army forces, such as in 1673 when theBlackheath Armywas assembled underMarshal Schombergto serve in theThird Anglo-Dutch War.In 1709–10, army tents were set up on Blackheath to house a large part of the 15,000 or so German refugees from thePalatinateand other regions who fled to England, most of whom subsequently settled in America or Ireland.[17]

With Watling Street carrying stagecoaches across the heath, en route to north Kent and theChannelports, it was also a notorious haunt ofhighwaymenduring the 17th and 18th centuries. As reported in Edward Walford'sOld and New London(1878), "In past times it was planted withgibbets,on which the bleaching bones of men who had dared to ask for some extension of liberty, or who doubted the infallibility of kings, were left year after year to dangle in the wind. "[18]In 1909 Blackheath had a local branch of the London Society for Women'sSuffrage.[19]

Mineral extraction

[edit]The Vanbrugh Pits, known locally as the Dips,[20]are on the north-east of the heath. A former gravel workings site,[21]it has long been reclaimed by nature and form a feature in its near-flat expanse; particularly attractive in spring when itsgorseblossoms brightly.[22]

Vanbrugh Park

[edit]The remains of the pits and adjoining neighbourhood Vanbrugh Park, a north-east projection of Blackheath with its own church, so also termedSt John's Blackheath,[23]are named after SirJohn Vanbrugh,architect ofBlenheim PalaceandCastle Howard,who had a house with very large grounds adjoining the heath and its continuation Greenwich Park. The house which was originally built around 1720 remains, remodelled slightly,Vanbrugh Castle.In his estate he had 'Mince Pie House' built for his family, which survived until 1911.[24]

Its church,St John the Evangelist's,was designed in 1853 byArthur Ashpitel.[25]TheBlackheath High Schoolbuildings on Vanbrugh Park include theChurch Army Chapel.

Blackheath Park

[edit]

Blackheath Park occupies almost all of former 0.4-square-mile (1.0 km2) Wricklemarsh Manor.[26]Developed intoupper middle classhomes byJohn Cator,it forms the south-east of Blackheath: from Lee Road, Roque Lane, Fulthorp Road and the Plantation to all houses and gardens of right-angled Manor Way. Built up in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, it contains large and refinedGeorgianandVictorianhouses – particularlyMichael Searles' crescent of semi-detached/terrace houses linked by colonnades, The Paragon (c. 1793-1807).[27]Its alternate name, the Cator Estate, extends to lands earlier those of SirJohn Morden,whoseMorden College(1695) is a landmark in the north, with views of the heath. The estate has 1950s and '60sSpanhouses and flats with gardens with discreet parking.

Its church (St Michael & All Angels) is dubbed theNeedle of Kentin honour of its tall, thin spire (it is also nicknamed theDevil's Pickor theDevil's Toothpick).

Other churches

[edit]

The Church of the Ascension (seelocal II*listed buildings) was founded by Susannah Graham late in the 17th century.[28]Its rebuilding was arranged about 1750 by her descendant, the1st Earl of Dartmouth.[28]Further rebuilding took place in the 1830s leaving at least parts of the east end from the earlier rebuild. At this time galleries for worshippers overlooked three sides.[28]

Ownership and management of the heath

[edit]In 1871 the management of the heath passed by statute to theMetropolitan Board of Works.Unlike the commons of Hackney, Tooting Bec and Clapham, its transfer was agreed at no expense, because theEarl of Dartmouthagreed to allow the encroachment to his manorial rights. It is held in trust for public benefit under the Metropolitan Commons Act of 1886. It passed to theLondon County Councilin 1889, then to theGreater London Council,then in 1986 to the two boroughs of Greenwich and Lewisham, as to their respective extents. No trace can be found of use as common land but only as minimal fertility land exploited by its manorial owners (manorial waste) and mainly for small-scale mineral extraction. Main freeholds (excluding many roads) vest in the Earl of Dartmouth and, as to that part that was the Royal Manor of Greenwich, theCrown Estate.The heath's chief natural resource is gravel, and the freeholders retain rights over its extraction.

Sport

[edit]In 1608, according to tradition, Blackheath was the place wheregolfwas introduced to England – the Royal Blackheath Golf Club[29](based in nearbyElthamsince 1923) was one of the first golf associations established (1766) outsideScotland.Blackheath also gave its name to the firsthockeyclub, established during the mid 19th century.

In the 18th century, Blackheath was the home ofGreenwich Cricket Cluband a venue forcricketmatches. The earliest known senior match wasKentvLondonin August 1730. A contemporary newspaper report said "the Kentish champions would have lost their honours by being beat at one innings if time had permitted".[30]The last recorded match was Kent v London in August 1769, Kent winning by 47 runs.[31]

Cricket continued to be played on the 'Heath' but at a junior level. By 1890,London County Councilwas maintaining 36 pitches. Blackheath Cricket Club[32]has been part of the sporting fabric of the area, joining forces with Blackheath Rugby Club in 1883 to purchase and develop theRectory Fieldas a home ground in Charlton. Blackheath Cricket Club hosted 84 first-classKent Countymatches between 1887 and 1971.

Blackheath Rugby Club,founded in 1858, is one of the oldest documentedrugbyclubs in the world[33]and was located until 2016 atRectory Fieldon Charlton Road. The Blackheath club also organised the world's first rugby international (betweenEnglandandScotlandinEdinburghon 27 March 1871) and hosted the first international between England andWalesten years later – the players meeting and getting changed at the Princess of Wales public house.Blackheathwas one of the 12 founding members ofthe Football Associationin 1863, as well as nearbyBlackheath Proprietary SchoolandPercival House (Blackheath).

Along with neighbouringGreenwich Park,Blackheath is the start point of theLondon Marathon.[34]This maintains a connection withathleticsdating back to the establishment of the Blackheath Harriers (nowBlackheath and Bromley Harriers Athletic Club) in 1869. One of the Marathon start routes runs past the entrance to Blackheath High School for Girls, home of Blackheath Fencing Club.[35]

There is also a long history ofkite flyingon the heath.

Geography

[edit]Blackheath is one of the largest areas ofcommon landinGreater London,with 85.58 hectares (211.5 acres) of protected commons.[36]The heath is managed by Lewisham and Greenwich councils.[37]Highlights on the Greenwich side include the Long Pond (also known as Folly Pond), close to the main entrance of Greenwich Park.[38]On the Lewisham side are three ponds, with Hare and Billet pond considered to be the most natural and probably the best wildlife habitat.[39][40]Lewisham retains important areas of acid grassland that support locally rare wild plants such asCommon stork's bill,Fiddle dockandSpotted medick.Key areas are to the east of Granville Park between South Row and Morden Row and on the cricket field east of Golfers Road.[41][42]

The heath's habitat was well known to early botanists. In the 18th centuryCarl Linnaeusreportedly fell to his knees to thank God when he first saw the gorse growing there. However, this disputed account is more often attributed toPutney Heath.[43]This environment supported both the flora and fauna of wild grassland. In 1859, Greenwich Natural History Society recorded a wide list of animal species, includingnatterjack toads,hares,common lizards,bats,quail,ring ouzelandnightingale.Today, bats remain and migrating ring ouzel may occasionally be seen in spring.[42]

Extensive mineral extraction in the 18th and early 19th centuries, when gravel, sand and chalk were extracted left the heath transformed. This left large pits in many parts. In 1945 pits were filled with bomb rubble fromWorld War II,then covered with topsoil and seeded withrye grass,leaving Vanbrugh Pits to the north-east side and Eliot Pits in the south-west. Infilled areas stand out, especially in late spring and early summer, from their deep-green rye grass.[42]

Culture and community

[edit]

Two clusters of amenities vie for retail and leisure: the "Village" aroundBlackheath railway stationto the south of the heath and the "Standard" in the north of St Johns/Vanburgh Park i.e. beyond the A2 road, named after the Royal Standard pub[44](inGreenwich). The north of the green is in theWestcombe Parkneighbourhood, which has its own railway station about 400 metres north – part of East Greenwich.[12]The total 0.35-hectare (0.9-acre) green and fountain sub-green was at first onevillage green,known during the 18th century as Sheepgate Green, beside a crossroads of what was the London-Dover road. Around 1885 local philanthropist William Fox Batley had it refurbished and it became known as Batley Green or Batley Park;[45][46]Batley's contribution is recorded in an inscription on a memorial fountain.

Just south of the railway station is theBlackheath Conservatoire of Music and the Arts.It is located close toBlackheath Halls,a concert venue today owned and managed byTrinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance.To the north of the railway station, in Tranquil Vale,All Saints' Parish Hallis a locally listed building inArts and Crafts style,built in 1928. It has housed theMary Evans Picture Librarysince 1988.[47]

The heath was host to an annual fireworks display on the Saturday in November closest toGuy Fawkes Night.This was jointly organised and financed by the London Boroughs of Greenwich and Lewisham, but Greenwich Council withdrew its share of the funding in 2010.[48]The event was suspended during theCOVID-19 pandemicin 2020, and central government funding cuts forced its suspension in 2021[49]and again in 2022.[50]

In September 2014, the inauguralOn Blackheathfestival was hosted on the heath. The line-up includedMassive Attack,Frank TurnerandGrace Jones.[51]The festival was repeated in September in 2015 (includedElbow,MadnessandManic Street Preachers),[52]2016 (includedPrimal Scream,JamesandSqueeze), 2017 (includedThe Libertines,TravisandMetronomy),[53]and 2018 (included Squeeze,De La SoulandPaloma Faith)[54]then moved to July in 2019 (includedJamiroquai,Grace Jones,Soul II Soul).[55]The event was cancelled during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

Transport

[edit]

Rail

[edit]Blackheath stationserves the area withNational Railservices toLondon Victoria,London Charing Cross,London Cannon Street,Slade GreenviaBexleyheath,Dartfordvia Bexleyheath or viaWoolwich ArsenalandGravesend.

Westcombe Park stationalso serves northern parts of Blackheath, with National Rail services toLutonviaLondon Blackfriars,London Cannon Street,Barnehurstvia Woolwich Arsenal,Crayfordvia Woolwich Arsenal andRainhamvia Woolwich Arsenal.

Buses

[edit]Blackheath is served byLondon Busesroutes53,54,89,108,202,286,335,380,386,422,N53andN89.These connect it with areas includingBexleyheath,Bow,Catford,Charlton,Crystal Palace,Deptford,Elephant & Castle,Eltham,Greenwich,Kidbrooke,Lee,Lewisham,New Cross,Plumstead,North Greenwich,Sidcup,Slade Green,Stratford,Sydenham,WellingandWoolwich.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^"Lewisham Ward population 2011".Neighbourhood Statistics.Office for National Statistics. Archived fromthe originalon 21 October 2016.Retrieved13 October2016.

- ^"Blackheath Westcombe Demographics (Greenwich, England)".blackheath-westcombe.localstats.co.uk.Retrieved13 October2016.

- ^"Area guide for Blackheath".Kinleigh Folkard & Hayward.

- ^abMills, A.D. (11 March 2010).Dictionary of London Place Names.Oxford.ISBN978-0199566785.

- ^abcdA Topographical Dictionary of England,ed.S. Lewis(London, 1848), pp. 270-275. British History Onlinehttp://www.british-history.ac.uk/topographical-dict/england/pp270-275,accessed 11 August 2019.

- ^se3.org.ukSt Michael and All Angels community website

- ^St John's, Blackheathshowing as offshoot E.P. of Greenwich E.P. since 1854Vision of Britain(website), © 2009–2017, theUniversity of Portsmouth

- ^All Saints, BlackheathE.P. an offshoot E.P. of Lewisham E.P. since 1859Vision of Britain(website), © 2009–2017, theUniversity of Portsmouthand others

- ^The Ascension, Blackheath– an offshoot E.P. of Lewisham E.P. since 1883Vision of Britain(website), © 2009–2017, theUniversity of Portsmouthand others.

- ^Blackheath Park(St Michael and All Angels, formerly St Peter's) – an offshoot E.P. of Charlton E.P., Kidbrooke Liberty and Lee E.P. since 1886Vision of Britain(website), © 2009–2017, theUniversity of Portsmouthand others.

- ^abUnits covering this areaVision of Britain(website), © 2009–2017, theUniversity of Portsmouthand others

- ^abParish locator and church information by grid reference,A Church Near You,Church of England,retrieved 2019-08-11

- ^Boundaries of Boundary Map of Kidbrooke Pariochial Liberty/Civil ParishVision of Britain(website), © 2009–2017, theUniversity of Portsmouthand others.

- ^Dartford Grammar School."Roman and Saxon Roads and Transport".dartfordarchive.org.uk.Kent County Council.

- ^Patrick Hanks; Flavia Hodges; A. D. Mills; Adrian Room (2002).The Oxford Names Companion.Oxford: the University Press. p. 1003.ISBN978-0198605614.

- ^"Wat Tyler and the Peasants Revolt".Historic UK.Retrieved3 December2020.

- ^Lucy Forney Bittinger,The Germans in Colonial Times(Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1901), p.67

- ^'Blackheath and Charlton',Old and New London:Volume 6 (1878), pp. 224-236accessed: 4 November 2009

- ^By Elizabeth Crawford, ed.The Women's Suffrage Movement: a reference guide, 1866-1928,s.v."Blackheath"

- ^"History | Friends of Westcombe Woodlands".Retrieved3 December2020.

- ^"London Gardens Online".London Gardens Online.Retrieved15 June2013.

- ^"Vanbrugh Pits on Blackheath".Lewisham.gov.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 28 July 2013.Retrieved15 June2013.

- ^St John's Blackheath: Parish locator and church information by grid reference,A Church Near You,Church of England,retrieved 2019-08-11

- ^"Mince Pie House, Vanbrugh Fields, Blackheath, c. 1910 | Lewisham Galleries".Ideal Homes. 29 September 2010.Retrieved15 June2013.

- ^Homan, Roger (1984).The Victorian Churches of Kent.Chichester: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. pp. 30–31.ISBN0-85033-466-7.

- ^In 1669,Sir John Morden, 1st Baronetpurchased it for £4,200; the mansion and 283 acres (1.15 km2) were sold in 1783 bySir Gregory Page-Turner, 3rd Baronetfor £22,000 to John Cator.

- ^Howard Colvin,Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600-1840,3rd ed. 1995,s.v."Searles, Michael".

- ^abcHistoric England."Church of The Ascension (1192114)".National Heritage List for England.

- ^"Our History: Royal Blackheath Golf Club – The Oldest Golf Club in the world".Archived fromthe originalon 15 July 2011.Retrieved15 July2011.

- ^Buckley, p. 4.

- ^Buckley, p. 52.

- ^"blackheathcc.com".blackheathcc.com.Retrieved15 August2013.

- ^"The Elders – the world's oldest Rugby Clubs – WhereToPlayRugby News".Retrieved3 December2020.

- ^"Course History".virginmoneylondonmarathon.com.Retrieved3 December2020.

- ^"blackheathfencing.org.uk".blackheathfencing.org.uk.Retrieved15 August2013.

- ^"Common Land and the Commons Act 2006".Defra.13 November 2012.Retrieved3 February2013.

- ^"Lewisham Council - Local parks - Blackheath".Lewisham.gov.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 31 August 2013.Retrieved15 June2013.

- ^"Blackheath - Greenwich".Royalgreenwich.gov.uk. 30 April 2012.Retrieved15 June2013.

- ^"Lewisham Council - Local parks - Ponds on Blackheath".Lewisham.gov.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 3 July 2012.Retrieved15 June2013.

- ^"Hare and Billet Pond".Nature Conservation Lewisham. 5 October 2012.Retrieved15 June2013.

- ^"Lewisham Council - Local Parks - Grasslands on Blackheath".Lewisham.gov.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 31 August 2012.Retrieved15 June2013.

- ^abc"Lewisham Council - Local parks - Habitat changes and ecological decline of Blackheath".Lewisham.gov.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 31 August 2012.Retrieved15 June2013.

- ^Fries, Theodor Magnus; Jackson, Benjamin Daydon (2011).Linnaeus.Cambridge University Press. p. 158.ISBN9781108037235.

- ^TfLhttp://content.tfl.gov.uk/bus-route-maps/blackheath-royal-stand.pdf

- ^Westcombe Park Conservation Area: Character Appraisal, March 2010.Accessed: 20 July 2015

- ^Rimel, Diana (2006), "History of the Standard",Westcombe NewsArchived13 March 2011 at theWayback Machine,February 2006, p.6. Accessed: 20 July 2015.

- ^"Mary Evans Picture Library – Client Update".maryevans.com.Retrieved3 December2020.

- ^"BLACKHEATH: Greenwich Council pulls out of fireworks display".Newsshopper.co.uk. 17 September 2010.Retrieved29 August2011.

- ^Uyal, Berk (2 November 2022)."Blackheath Fireworks 2022: Lewisham Council confirms cancelled event".News Shopper.Retrieved20 February2023.

- ^"Blackheath fireworks".Lewisham Council.Retrieved20 February2023.

- ^Saturday, 13 September 2014 – Sunday, 14 September 2014,On Blackheath. Retrieved: 24 August 2015.

- ^2015 Headliners[usurped],On Blackheath. Retrieved: 24 August 2015.

- ^Ellis, David (6 September 2017)."OnBlackheath Festival 2017 tickets, line up and everything you need to know".Evening Standard.Retrieved20 February2023.

- ^Trenaman, Calum; Fletcher, Harry (7 September 2018)."OnBlackheath: Tickets, line-up and everything you need to know".Evening Standard.Retrieved20 February2023.

- ^Embley, Jochan (10 July 2019)."OnBlackheath festival 2019: Tickets, line-up, stage times, food and more".Evening Standard.Retrieved20 February2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Barker, Felix.Greenwich and Blackheath Past(Historical Publications, 1993)

- Henderson, Ian T. & David I. Stirk.Royal Blackheath(1981)

- Rhind, Neil.Blackheath Centenary 1871–1971: A Short History of Blackheath from Earliest Times(GLC, 1971)

External links

[edit]- Blackheath, London

- 1730 establishments in England

- Areas of London

- Common land in London

- Conservation areas in London

- Cricket grounds in London

- Defunct cricket grounds in England

- Defunct sports venues in London

- Districts of the Royal Borough of Greenwich

- Districts of the London Borough of Lewisham

- District centres of London

- English cricket venues in the 18th century

- Nature reserves in the London Borough of Lewisham

- Sports venues completed in 1730

- Sports venues in London