Boeing 247

| Boeing 247 | |

|---|---|

United Air Lines Boeing 247D in flight | |

| General information | |

| Type | Passenger airliner |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Boeing |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary user | Boeing Air Transport |

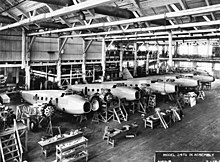

| Number built | 75 |

| History | |

| Introduction date | May 22, 1933[1] |

| First flight | February 8, 1933 |

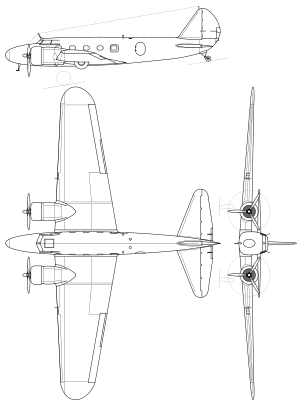

TheBoeing Model 247is an early Americanairliner,and one of the first such aircraft to incorporate advances such as all-metal (anodized aluminum)semimonocoqueconstruction, a fullycantilevered wing,andretractable landing gear.[2][3]Other advanced features included control surfacetrim tabs,anautopilotandde-icing bootsfor the wings andtailplane.[4]The 247 first flew on February 8, 1933, and entered service later that year.[5]

Design and development

[edit]

Boeing introducing a host of aerodynamic and technical features into a new commercial airliner building on work with the earlierMonomail(Models 200, 221, 221A) mailplanes andB-9bomber designs. The Boeing 247 was faster than the best U.S. fighter of its day, the open-cockpitbiplaneBoeing P-12.[6]The low landing speed of 62 mph (100 km/h) avoided the need for flaps, and pilots learned that at speeds as low as 10 mph (16 km/h), the 247 could be taxied "tail high" for ease of ground handling.[7]

The 247 could fly on one engine. With controllable-pitch propellers, the 247 could maintain 11,500 ft (3,500 m) at maximum gross weight on one engine.[8]Aside from its size, much lower wing loading, and thewing sparobstructing the cabin, many of its features became the norm for airliners, including theDouglas DC-1,beforeWorld War II.[5]Originally planned as a 14-passenger airliner powered byPratt & Whitney R-1690 Hornetradial engines,the preliminary review of the design concept by United Air Lines' pilots had resulted in a redesign to a smaller, less capable configuration, powered byR-1340 Wasp engines.[9][10][11]

One concern of the pilots was that in their view, few airfields could safely take an eight-ton aircraft.[10]They also objected to the Hornet engines, which had a detonation problem when using the available lowoctanefuel, and suffered from excessive vibration.[12]Pratt & Whitney's chief engineer,George Mead,knew the problem would be resolved eventually,[10]but P&W's president,Frederick Rentschleracquiesced to the airline pilots' demand. The decision created a rift between Mead and Rentschler.[10]Despite the disagreements, the 247 would be Boeing's showcase exhibit at the1933 Chicago World's Fair.[13]

The slope of the early 247'swindshieldwas reversed from normal. This was a design solution, also used on other contemporary aircraft, to the problem of control panel instrument lights reflecting off the windshield, but the reversed windshield reflected ground lights instead, especially during landings, and it also increased drag.[14][15]By the introduction of the 247D, the windshield was sloped normally, and the glare was resolved with a glarescreen extension over the panel.[16]

Boeing incorporated design elements to enhanced passenger comfort, such as the thermostat controlled, air conditioned, and noise-proofed cabin. The crew included a pilot and copilot, as well as a flight attendant (then known as a "steward" ), who could tend to passenger needs.[17]The main landing gear did not fully retract; a portion of the wheels extended below thenacelles,typical of designs of the time, as a means of reducing structural damage in a wheels-up landing. The tailwheel was not retractable. While the Model 247 and 247A hadspeed-ringenginecowlingsand fixed-pitchpropellers,the Model 247D incorporatedNACA cowlingsandvariable-pitch propellers.[18]

Operational history

[edit]

As the 247 emerged from its test and development phase, the company further showcased its capabilities by entering a long-distance air race in 1934, theMacRobertson Air RacefromEnglandtoAustralia.During the 1930s, aircraft designs were often proven in air races and other aerial contests. A modified 247D was entered, flown by ColonelRoscoe TurnerandClyde Pangborn.[19]The 247, race number "57", was essentially a production model, but all airliner furnishings were removed to accommodate eight additional fuselage fuel tanks.[20]The MacRobertson Air Race attracted aircraft entries from all over the globe, including both prototypes and established production types, with the grueling course considered an excellent proving ground, as well as an opportunity to gain worldwide attention. Turner and Pangborn came in second place in the transport section (and third overall), behind the Boeing 247's eventual rival, the newDouglas DC-2.[21]

Being the winner of the 1934 U.S.Collier Trophyfor excellence in aviation design, the first 247 production orders were earmarked for William Boeing's airline,Boeing Air Transport.[20]The 247 was capable of crossing the United States from east to west eight hours faster than its predecessors, such as theFord TrimotorandCurtiss Condor.Entering service on May 22, 1933, a Boeing Air Transport 247 set a cross-country record of19+1⁄2hours on itsSan Franciscoto New York City inaugural flight.[1][22]

Boeing sold the first 60 247s, an unprecedented $3.5 million order, to its affiliated airline, Boeing Air Transport (part of theUnited Aircraft and Transport Corporation,UATC), at a unit price of $65,000.[5][8]TWA (Transcontinental & Western Air) also ordered the 247, but UATC declined the order, which resulted in TWA PresidentJack Fryesetting out requirements for a new airliner and fundingDon Douglasto design and build theDouglas DC-1prototype. Douglas eventually developed the design into the DC-2 andDC-3.[5]

The Boeing design had been the first to enter series production, but the 247 proved to have some serious deficiencies. Airlines considered its limited capacity a drawback, since it carried only 10 passengers, in five rows with a seat on each side of the aisle, as well as astewardess.Compared to the more spacious DC-2 and later DC-3, the passenger count was too few to make it a commercially viable airliner.[21]Another feature influencing passenger comfort was that the 247's main wing spar ran through the cabin, so persons moving through the cabin had to step over it.[23]TheLockheed Model 10 Electrahad a similar configuration, and while it was a more compact design, the Electra managed to carry the same number of passengers at a slightly better overall performance, and at a lower cost-per-mile.[21]

Seventy-five 247s were built; Douglas collected 800 civil orders for DC-3s before thePearl Harborattack, and produced over 10,000 DC-3s, including wartime production ofC-47s,while the rival Lockheed Electra "family" was eventually to reach over 3,000 in its various civil and military variants. Boeing Air Transport bought 60 examples,United Aircraft Corp.10,Lufthansaordered three, but only two were delivered,[24][25]and one went to a private owner in China. While the industry primarily standardized on Boeing's competitors, many of United's aircraft were later purchased byWestern Air Expressat "bargain-basement prices".[26]

The 247 remained in airline service untilWorld War II,when several were converted into C-73 transports and trainers. TheRoyal Canadian Air Force's121 Squadronoperated seven 247Ds as medium transports during the early part of the war.[27]One of these aircraft was donated to theRoyal Air Force(RAF) forradartesting, where it was renumberedDZ203.DZ203 was passed among several units in the RAF before being used to make the world's first fully automaticblind landingon 16 January 1945.[28]

Warlord"Young Marshal" Zhang Xueliangordered two Boeing 247Ds for hisair force.He used one of them, namedBai-Ying(White Eagle), during theXi'an incidentin 1936, during which he flew into the opposing Nationalist army's camp atSian(now rendered asXi'an)under a secret truce, and had their leader, GeneralissimoChiang Kai-shek,arrested, ending the civil war between the Communist and Nationalist armies, so they could fight together against the Japanese invaders.[29]

A number of specially modified variants included a Boeing 247Y appropriated from United for Air Corps use as a test aircraft fitted with two machine guns in the nose. The same installation later was fitted to a 247Y owned by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. This aircraft also featured a Colt.50 in (12.7 mm) machine gun in a flexible mount.[30]A 247D purchased by the British RAF became a testbed forinstrument approachequipment and received a nonstandard nose, new powerplants, and fixed landing gear.[31]Some 247s were still flying in the late 1960s as cargo transports and business aircraft.[21]

The Turner/Pangborn 247D still exists. Originally flown on September 5, 1934, it was leased from United Airlines for the 1934 MacRobertson Air Race and returned to United, where it served in regular airline service until 1937. Subsequently, the 247D was sold to the Union Electric Company of St. Louis for use as an executive transport. The Air Safety Board purchased the aircraft in 1939 and it remained in use for 14 years before it was donated to theNational Air and Space Museum,Washington, DC.It is displayed today with two sets of markings, the left side is marked as NR257Y, in Colonel Turner's 1934 MacRobertson Air Race colors, while the right side is painted in United Airlines livery, as NC13369.[19]

Variants

[edit]

- Model 247

- Twin-engined civil transport airliner, initial production version

- 247A

- Powered by new 625 hp (466 kW) P&W Wasp, on special order for Deutsche Luft Hansa in 1934

- 247E

- This designation was given to the first Boeing 247 aircraft, it was used to test a number improvements that were later incorporated into the Boeing 247D.

- 247D

- Original one-off was a race aircraft designed for theMacRobertson Air Race;use of Hamilton Standard variable-pitch propellers allowed for a 7 mph (11 km/h) gain; the 247D configuration incorporated in production series bearing the same name.

- 247Y

- Armed version, one exported to China, second used for trials

- C-73

- Designation for Boeing 247D airliners impressed into military service in USAAF, 27 in total

- Model 280

- Proposed development of Boeing 247 with 14 seats and 700 hp (520 kW) P&W Hornet engines

Operators

[edit]Civil operators

[edit]

- Viação Aérea Bahianaoperated one aircraft.

- Private owner operated one aircraft.

- Boeing Air Transport(laterUnited Air Lines) operated 60 aircraft.

- Empire Air Lines

- National Parks Airways

- Pennsylvania Central Airlines

- United AircraftCorporation operated 10 aircraft.

- Wien Air Alaska

- Western Air Express,the predecessor ofWestern Airlines,received some of ex-United Aircraft Corporation aircraft.

- Woodley Airways

- Wyoming Air Service

Military operators

[edit]Accidents and incidents

[edit]- October 10, 1933

- United Air Lines247,NC13304(c/n 1685), was probably the first victim ofsabotage of a commercial airliner.The aircraft, en route fromClevelandtoChicago,was destroyed by anitroglycerin-based explosive device overChesterton, Indiana.[33]All seven on board were killed.

- November 9, 1933

- APacific Air Transport247,NC13345(c/n 1727), crashed on takeoff after the pilot became disoriented in fog and low visibility; four of ten on board died.[34]

- November 24, 1933

- ANational Air Transport247,NC13324(c/n 1705), was being ferried from Chicago to Kansas City when it crashed near Wedron, Illinois, killing all three crew.[35]

- February 23, 1934

- A United Air Lines 247,NC13357(c/n 1739),crashedin Parley's Canyon in fog near Salt Lake City, killing all eight on board.

- December 20, 1934

- United Air Lines Flight 6, a 247 (NC13328,c/n 1709), struck a tree and crashed near Western Springs, Illinois, due to carburetor icing; all four on board survived. The aircraft involved was repaired and converted to 247D standard in July 1935 and returned to service;[36]the aircraft was pressed into USAAF service in 1942 and redesignated as C-73 with tail number42-57210.The aircraft was damaged in a wind storm at Duncan Field, Texas, on August 30, 1942, and was written off.[37]

- March 24, 1935

- The sole 247 operated byLufthansa(D-AGAR,c/n 1945) was damaged beyond economical repair in a collision with anAir Franceaircraft on the ground atNurembergand then scrapped[25]

- September 1, 1935

- Western Air Express247,NC13314(c/n 1695), was being ferried from Burbank, California, to Saugus, California, when it struck high tension power lines after takeoff, killing all three on board.[38]

- October 7, 1935

- United Airlines Flight 4,a 247D (c/n 1698), went down about 10 mi (16 km) west of Cheyenne, Wyoming due to pilot error. Three crew and nine passengers killed, there were no survivors.[39]

- October 30, 1935

- United Air Lines Boeing 247D,NC13323(c/n 1704), crashed during an instrument checkflight near Cheyenne, killing the four crew members aboard.[40]

- December 15, 1936

- Seven died whenWestern Air ExpressFlight 6, a 247D,[41]en route fromBurbank, California,toSalt Lake CityviaLas Vegas,crashed just below Hardy Ridge onLone PeakinUtah.[42]The major parts of the aircraft were hurled over the ridge and fell over 1,000 ft (300 m) into a basin below.[41]

- December 27, 1936

- United Airlines Trip 34,a 247D (c/n 1737), crashed at the head of Rice Canyon,Los Angeles County, California,due to pilot error; all 12 on board died.

- January 12, 1937

- Western Air Express Flight 7,a 247D (c/n 1696) flight from Salt Lake City to Burbank, crashed into a mountain nearNewhall, California,killing five. Among the dead was Martin Johnson ofMartin and Osa Johnsonfame (adventurers, authors, and documentary filmmakers).[43]

- August 13, 1937

- A 247 being operated by theLuftwaffe'sproving ground atRechlin(formerlyD-AKINofLufthansa,c/n 1944) crashed at Hannover, Germany, during a test flight,[25]killing seven of eight on board. The aircraft was being used as a testbed for an experimental autopilot.

- March 13, 1939

- A SCADTA 247D,C-149,crashed nearManzanares, Caldas,Colombia, killing all eight on board.[44]

- February 27, 1940

- A SCADTA 247D,C-140,struck El Mortino mountain nearTona, Santander,Colombia, killing all 11 on board.[45]

- July 30, 1942

- A Northwest Airlines C-73,42-68639(c/n 1717, former NC13335), crashed and burned on takeoff fromWold Chamberlain Field,nearMinneapolis,Minnesota, killing all 10 on board.[46]

Surviving aircraft

[edit]

- c/n 1699,CF-JRQ

- Exhibited inCanada Aviation and Space Museum,Ottawa.Donated to the museum in 1967 byCalifornia Standard OilofCalgary,Alberta.[47]

- c/n 1722,N18E

- Exhibited in theNational Museum of Science and Industry,Wroughton,UK

- c/n 1729,N13347

- Static display, flown after restoration at theMuseum of FlightRestoration Center,Paine Field,Snohomish County, Washington,USA, to the Museum of Flight main facility on 26 April 2016 where it was subsequently installed in that museum's Air Park.[48]

- c/n 1953,NC13369/NR257Y

- Exhibited in the Hall of Air Transportation at theNational Air and Space Museum,Washington, D.C.,USA, withUnited Air Linescolors and registration asNC13369on its right fuselage and wing and asNR257YwithMacRobertson Air Racemarkings on its left side.[19]

Specifications (Boeing 247D)

[edit]

Data fromBoeing aircraft since 1916[49]

General characteristics

- Crew:Three

- Capacity:10 passengers + baggage and 400 lb (181 kg) of mail

- Length:51 ft 7 in (15.72 m)

- Wingspan:74 ft 1 in (22.58 m)

- Height:12 ft 1.75 in (3.7021 m)

- Wing area:836.13 sq ft (77.679 m2)

- Airfoil:Boeing 106B[50]

- Empty weight:8,921 lb (4,046 kg)

- Max takeoff weight:13,650 lb (6,192 kg)

- Fuel capacity:273 US gal (227 imp gal; 1,030 L)

- Powerplant:2 ×Pratt & Whitney R-1340 S1H1-G Wasp9-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engines, 500 hp (370 kW) each at 2,200 rpm at 8,000 ft (2,400 m)

- Propellers:2-bladed variable-pitch propellers

Performance

- Maximum speed:200 mph (320 km/h, 170 kn)

- Cruise speed:189 mph (304 km/h, 164 kn) at 12,000 ft (3,700 m)

- Range:745 mi (1,199 km, 647 nmi)

- Service ceiling:25,400 ft (7,700 m)

- Absolute ceiling:27,200 ft (8,291 m)

- Rate of climb:1,150 ft/min (5.8 m/s)

Notable appearances in media

[edit]See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

Notes

[edit]- ^abBryan 1979, p. 109.

- ^"Model 247 Commercial Transport."ArchivedJanuary 18, 2008, at theWayback Machineboeing.com,2009. Retrieved: June 14, 2010.

- ^van der Linden 1991,pp. xi–xii.

- ^Bryan 1979, p. 110.

- ^abcdGould 1995, p. 14.

- ^Serling 1992, p. 19.

- ^Seely 1968, p. 58.

- ^abSeely 1968, p. 56.

- ^Serling 1992, p. 20.

- ^abcdFernandez 1983, pp. 74–78, 104–105.

- ^"247D Type Certificate"(PDF).Federal Aviation Administration.FAA. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 28 December 2016.Retrieved5 May2016.

- ^McCutcheon, Kimble D. (July 3, 2015)."Pratt & Whitney Single-Row Radials (Wasp and Hornet)".Aircraft Engine Historical Society.

- ^Serling 1992, p. 22.

- ^Pearcy 1995

- ^van der Linden 1991,p. 93.

- ^Holcomb, Kevin."The Boeing 247."Airminded.net webpage showing initial and final windshield angles and glare screen installation in the 247D, 2009. Retrieved: July 26, 2009.

- ^van der Linden 1991,p. 1.

- ^"Boeing Model 247: First modern airliner."acepilots.com,2007. Retrieved: July 26, 2009.

- ^abcd"NASM Boeing 247D."ArchivedNovember 24, 2007, at theWayback MachineWayback archiveof NASM Boeing 247D, originally revised May 5, 2001. Retrieved: July 26, 2009.

- ^abBoeing Company 1969, p. 35.

- ^abcd"Boeing Model 247- USA."The Aviation History On-Line Museum,November 19, 2004. Retrieved: July 26, 2009.

- ^Pask, Alexander (11 September 2019)."Boeing 247: The First of Monoplane Firsts".internationalaviationhq.com.

- ^Serling 1992, p. 21.

- ^ab'Das Große Buch der Lufthansa' Günter Stauch(Hrsg.) GeraMond Verlag 2003ISBN3-7654-7174-7pp. 70–73

- ^abcd'Der Deutsche Luftverkehr 1926–1945' Karl-Dieter Seifert Bernard & Graefe Verlag, Bonn 1999ISBN3-7637-6118-7pp.330–331

- ^Serling 1992, p. 23.

- ^"Boeing 247D".rcaf.com.2009. Archived fromthe originalon 21 May 2006.Retrieved13 February2021.

- ^Burrows, Stephen; Layton, Michael (2020).Top Secret Worcestershire.Brewin Books. p. 44.ISBN978-1858586151.

- ^Johnson, Robert Craig (1996)."China's Air Forces in the Struggle Against Japan".worldatwar.net.Retrieved2021-01-20.

- ^Seely 1968, p. 63.

- ^Seely 1968, p. 69.

- ^Yenne 1989, pp. 54–59.

- ^"Seven die as plane crashes in flames".The New York Times.October 11, 1933. p. 1.

- ^"Accident Boeing 247 NC13345".Aviation Safety Network.Retrieved20 January2018.

- ^"Accident Boeing 247 NC13324".Aviation Safety Network.Retrieved20 January2018.

- ^"Incident Boeing 247 NC13328".Aviation Safety Network.Retrieved8 April2022.

- ^"Incident Boeing 247D (C-73) 42-57210".Aviation Safety Network.Retrieved20 January2018.

- ^"Accident Boeing 247 NC13314".Aviation Safety Network.Retrieved20 January2018.

- ^van der Linden 1971, p. 174.

- ^"Cheyenne, WY United Airlines Plane Crashes."Archived2014-02-22 at theWayback MachineAssociated PressforCentralia Daily Chronicle(Washington),October 31, 1935. Retrieved: December 5, 2011.

- ^ab"Aircraft Accident Report, December 15, 1936 crash."ArchivedAugust 23, 2011, at theWayback MachineDepartment of Commerce.Retrieved: November 8, 2009.

- ^"Confetti on Lone Peak."Time,June 21, 1937. Retrieved: November 8, 2009.

- ^Stokes, Keith."Martin and Osa Johnson Safari Museum".kansastravel.org.RetrievedJuly 26,2009.

- ^"Accident Boeing 247D C-149".Aviation Safety Network.Retrieved20 January2018.

- ^"Accident Boeing 247D C-140".Aviation Safety Network.Retrieved20 January2018.

- ^"Accident Boeing 247 (C-73) 42-68639".Aviation Safety Network.Retrieved20 January2018.

- ^"Boeing 247D."Archived2009-04-22 at theWayback MachineCanada Aviation and Space Museum Collection,2009. Retrieved: July 26, 2009.

- ^"Last Flight for Rare 1933 Boeing 247D Airliner".warbirdsnews.com.14 April 2016.Retrieved4 April2018.

- ^Bowers, Peter M. (1989).Boeing aircraft since 1916(3rd ed.). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 207–213.ISBN978-0870210372.

- ^Lednicer, David."The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage".m-selig.ae.illinois.edu.Retrieved16 April2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Boughton, Trevor W. (April–July 1980). "Talkback".Air Enthusiast.No. 12. p. 49.ISSN0143-5450.

- Bowers, Peter M.Boeing aircraft since 1916.London: Putnam Aeronautical Books, 1989.ISBN0-85177-804-6.

- Bryan, C.D.B.The National Air and Space Museum.New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1979.ISBN0-8109-0666-X.

- Fernandez, Ronald.Excess Profits: The Rise of United Technologies.Boston, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1983.ISBN978-0-201-10484-4.

- Gould, William.Boeing(Business in Action). Bath, Avon, UK: Cherrytree Books, 1995.ISBN0-7451-5178-7.

- Mondey, David,The Concise Guide to American Aircraft of World War II.London: Chancellor, 1996.ISBN1-85152-706-0.

- Pearcy, Arthur.Douglas Propliners: DC-1–DC-7.Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing, 1995.ISBN1-85310-261-X.

- Pedigree of Champions: Boeing Since 1916, Third Edition.Seattle, Washington: The Boeing Company, 1969. No ISBN.WorldCat.

- Seely, Victor. "Boeing's Grand Old Lady."Air Classics,Vol. 4, No. 6, August 1968.

- Serling, Robert J.Legend & Legacy: The Story of Boeing and its People.New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992.ISBN0-312-05890-X.

- Taylor, H. A. "Boeing's Trend-Setting 247".Air Enthusiast,No. 9, February–May 1979, pp. 43–54.ISSN0143-5450.

- Taylor, H. A. "Talkback".Air Enthusiast,No. 10, July–September 1979, p. 80.ISSN0143-5450

- van der Linden, F. Robert.The Boeing 247: The First Modern Airliner.Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press, 1991.ISBN0-295-97094-4.Retrieved: July 26, 2009.

- Yenne, Bill.Boeing: Planemaker to the World.New York:, Crescent Books, 1989.ISBN0-517-69244-9.

External links

[edit]- Boeing: Historical Snapshot: Model 247/C-73 Transport

- Film of United Airlines Boeing 247 NC13364 taking off from Vancouver Airport 1934

- Gallery: Boeing 247 Images, including two of the interior and one of the retracted main gear

- Boeing Model 247: First modern airliner

- "From Mock Up To Latest Airliner,"Popular Mechanics,October 1932, early article on future Model 247

- "Keeping Them In The Air"Popular Mechanics,July 1935 photos and colored artwork of 247 pp.9–16

- Maintenance & service manual for the Boeing Model 247 transport airplane–The Museum of Flight Digital Collections