Molecular geometry

Molecular geometryis thethree-dimensionalarrangement of theatomsthat constitute amolecule.It includes the general shape of the molecule as well asbond lengths,bond angles,torsional anglesand any other geometrical parameters that determine the position of each atom.

Molecular geometry influences several properties of a substance including itsreactivity,polarity,phase of matter,color,magnetismandbiological activity.[1][2][3]The angles between bonds that an atom forms depend only weakly on the rest of molecule, i.e. they can be understood as approximately local and hencetransferable properties.

Determination

[edit]The molecular geometry can be determined by variousspectroscopic methodsanddiffractionmethods.IR,microwaveandRaman spectroscopycan give information about the molecule geometry from the details of the vibrational and rotational absorbance detected by these techniques.X-ray crystallography,neutron diffractionandelectron diffractioncan give molecular structure for crystalline solids based on the distance between nuclei and concentration of electron density.Gas electron diffractioncan be used for small molecules in the gas phase.NMRandFRETmethods can be used to determine complementary information including relative distances,[4][5][6] dihedral angles,[7][8] angles, and connectivity. Molecular geometries are best determined at low temperature because at higher temperatures the molecular structure is averaged over more accessible geometries (see next section). Larger molecules often exist in multiple stable geometries (conformational isomerism) that are close in energy on thepotential energy surface.Geometries can also be computed byab initio quantum chemistry methodsto high accuracy. The molecular geometry can be different as a solid, in solution, and as a gas.

The position of each atom is determined by the nature of thechemical bondsby which it is connected to its neighboring atoms. The molecular geometry can be described by the positions of these atoms in space, evokingbond lengthsof two joined atoms, bond angles of three connected atoms, andtorsion angles(dihedral angles) of threeconsecutivebonds.

Influence of thermal excitation

[edit]Since the motions of the atoms in a molecule are determined by quantum mechanics, "motion" must be defined in a quantum mechanical way. The overall (external) quantum mechanical motions translation and rotation hardly change the geometry of the molecule. (To some extent rotation influences the geometry viaCoriolis forcesandcentrifugal distortion,but this is negligible for the present discussion.) In addition to translation and rotation, a third type of motion ismolecular vibration,which corresponds to internal motions of the atoms such as bond stretching and bond angle variation. The molecular vibrations areharmonic(at least to good approximation), and the atoms oscillate about their equilibrium positions, even at the absolute zero of temperature. At absolute zero all atoms are in their vibrational ground state and showzero point quantum mechanical motion,so that the wavefunction of a single vibrational mode is not a sharp peak, but approximately aGaussian function(the wavefunction forn= 0 depicted in the article on thequantum harmonic oscillator). At higher temperatures the vibrational modes may be thermally excited (in a classical interpretation one expresses this by stating that "the molecules will vibrate faster" ), but they oscillate still around the recognizable geometry of the molecule.

To get a feeling for the probability that the vibration of molecule may be thermally excited, we inspect theBoltzmann factorβ≡ exp(−ΔE/kT),where ΔEis the excitation energy of the vibrational mode,ktheBoltzmann constantandTthe absolute temperature. At 298 K (25 °C), typical values for the Boltzmann factor β are:

- β= 0.089for ΔE=500 cm−1

- β= 0.008for ΔE= 1000 cm−1

- β= 0.0007 for ΔE= 1500 cm−1.

(Thereciprocal centimeteris an energy unit that is commonly used ininfrared spectroscopy;1 cm−1corresponds to1.23984×10−4eV). When an excitation energy is 500 cm−1,then about 8.9 percent of the molecules are thermally excited at room temperature. To put this in perspective: the lowest excitation vibrational energy in water is the bending mode (about 1600 cm−1). Thus, at room temperature less than 0.07 percent of all the molecules of a given amount of water will vibrate faster than at absolute zero.

As stated above, rotation hardly influences the molecular geometry. But, as a quantum mechanical motion, it is thermally excited at relatively (as compared to vibration) low temperatures. From a classical point of view it can be stated that at higher temperatures more molecules will rotate faster, which implies that they have higherangular velocityandangular momentum.In quantum mechanical language: more eigenstates of higher angular momentum becomethermally populatedwith rising temperatures. Typical rotational excitation energies are on the order of a few cm−1.The results of many spectroscopic experiments are broadened because they involve an averaging over rotational states. It is often difficult to extract geometries from spectra at high temperatures, because the number of rotational states probed in the experimental averaging increases with increasing temperature. Thus, many spectroscopic observations can only be expected to yield reliable molecular geometries at temperatures close to absolute zero, because at higher temperatures too many higher rotational states are thermally populated.

Bonding

[edit]Molecules, by definition, are most often held together withcovalent bondsinvolving single, double, and/or triple bonds, where a "bond" is ashared pairof electrons (the other method of bonding between atoms is calledionic bondingand involves a positivecationand a negativeanion).

Molecular geometries can be specified in terms of 'bond lengths', 'bond angles' and 'torsional angles'. The bond length is defined to be the average distance between the nuclei of two atoms bonded together in any given molecule. A bond angle is the angle formed between three atoms across at least two bonds. For four atoms bonded together in a chain, thetorsional angleis the angle between the plane formed by the first three atoms and the plane formed by the last three atoms.

There exists a mathematical relationship among the bond angles for one central atom and four peripheral atoms (labeled 1 through 4) expressed by the following determinant. This constraint removes one degree of freedom from the choices of (originally) six free bond angles to leave only five choices of bond angles. (The anglesθ11,θ22,θ33,andθ44are always zero and that this relationship can be modified for a different number of peripheral atoms by expanding/contracting the square matrix.)

Molecular geometry is determined by thequantum mechanicalbehavior of the electrons. Using thevalence bond approximationthis can be understood by the type of bonds between the atoms that make up the molecule. When atoms interact to form achemical bond,the atomic orbitals of each atom are said to combine in a process calledorbital hybridisation.The two most common types of bonds aresigma bonds(usually formed by hybrid orbitals) andpi bonds(formed by unhybridized p orbitals for atoms ofmain group elements). The geometry can also be understood bymolecular orbital theorywhere the electrons are delocalised.

An understanding of the wavelike behavior of electrons in atoms and molecules is the subject ofquantum chemistry.

Isomers

[edit]Isomersare types of molecules that share a chemical formula but have difference geometries, resulting in different properties:

- Apuresubstance is composed of only one type of isomer of a molecule (all have the same geometrical structure).

- Structural isomershave the same chemical formula but different physical arrangements, often forming alternate molecular geometries with very different properties. The atoms are not bonded (connected) together in the same orders.

- Functional isomersare special kinds of structural isomers, where certain groups of atoms exhibit a special kind of behavior, such as an ether or an alcohol.

- Stereoisomersmay have many similar physicochemical properties (melting point, boiling point) and at the same time very differentbiochemicalactivities. This is because they exhibit ahandednessthat is commonly found in living systems. One manifestation of thischiralityor handedness is that they have the ability to rotate polarized light in different directions.

- Protein foldingconcerns the complex geometries and different isomers thatproteinscan take.

Types of molecular structure

[edit]A bond angle is the geometric angle between two adjacent bonds. Some common shapes of simple molecules include:

- Linear:In a linear model, atoms are connected in a straight line. The bond angles are set at 180°. For example, carbon dioxide andnitric oxidehave a linear molecular shape.

- Trigonal planar:Molecules with the trigonal planar shape are somewhat triangular and in oneplane (flat).Consequently, the bond angles are set at 120°. For example,boron trifluoride.

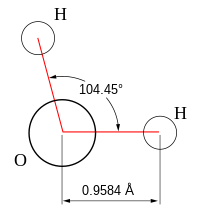

- Angular:Angular molecules (also calledbentorV-shaped) have a non-linear shape. For example, water (H2O), which has an angle of about 105°. A water molecule has two pairs of bonded electrons and two unshared lone pairs.

- Tetrahedral:Tetra-signifies four, and-hedralrelates to a face of a solid, so "tetrahedral"literally means" having four faces ". This shape is found when there arefour bonds all on one central atom,with no extra unsharedelectronpairs. In accordance with theVSEPR(valence-shell electron pair repulsion theory), the bond angles between the electron bonds arearccos(−1/3) = 109.47°. For example,methane(CH4) is a tetrahedral molecule.

- Octahedral:Octa-signifies eight, and-hedralrelates to a face of a solid, so "octahedral"means" having eight faces ". The bond angle is 90 degrees. For example,sulfur hexafluoride(SF6) is an octahedral molecule.

- Trigonal pyramidal:A trigonal pyramidal molecule has apyramid-like shapewith a triangular base. Unlike the linear and trigonal planar shapes but similar to the tetrahedral orientation, pyramidal shapes require three dimensions in order to fully separate the electrons. Here, there are only three pairs of bonded electrons, leaving one unshared lone pair. Lone pair – bond pair repulsions change the bond angle from the tetrahedral angle to a slightly lower value.[9]For example,ammonia(NH3).

VSEPR table

[edit]The bond angles in the table below are ideal angles from the simpleVSEPR theory(pronounced "Vesper Theory" )[citation needed],followed by the actual angle for the example given in the following column where this differs. For many cases, such as trigonal pyramidal and bent, the actual angle for the example differs from the ideal angle, and examples differ by different amounts. For example, the angle inH2S(92°) differs from the tetrahedral angle by much more than the angle forH2O(104.48°) does.

| Atoms bonded to central atom |

Lone pairs | Electron domains (Steric number) |

Shape | Ideal bond angle (example's bond angle) |

Example | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0 | 2 | linear | 180° | CO2 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | trigonal planar | 120° | BF3 | |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | bent | 120° (119°) | SO2 | |

| 4 | 0 | 4 | tetrahedral | 109.5° | CH4 |

|

| 3 | 1 | 4 | trigonal pyramidal | 109.5° (106.8°)[10] | NH3 | |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | bent | 109.5° (104.48°)[11][12] | H2O | |

| 5 | 0 | 5 | trigonal bipyramidal | 90°, 120° | PCl5 |

|

| 4 | 1 | 5 | seesaw | ax–ax 180° (173.1°), eq–eq 120° (101.6°), ax–eq 90° |

SF4 | |

| 3 | 2 | 5 | T-shaped | 90° (87.5°), 180° (175°) | ClF3 | |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | linear | 180° | XeF2 | |

| 6 | 0 | 6 | octahedral | 90°, 180° | SF6 |

|

| 5 | 1 | 6 | square pyramidal | 90° (84.8°) | BrF5 | |

| 4 | 2 | 6 | square planar | 90°, 180° | XeF4 | |

| 7 | 0 | 7 | pentagonal bipyramidal | 90°, 72°, 180° | IF7 |

|

| 6 | 1 | 7 | pentagonal pyramidal | 72°, 90°, 144° | XeOF−5 | |

| 5 | 2 | 7 | pentagonal planar | 72°, 144° | XeF−5 | |

| 8 | 0 | 8 | square antiprismatic | XeF2−8 | ||

| 9 | 0 | 9 | tricapped trigonal prismatic | ReH2−9 |

|

3D representations

[edit]- Lineorstick– atomic nuclei are not represented, just the bonds as sticks or lines. As in 2D molecular structures of this type, atoms are implied at each vertex.

|

|

|

|

- Electron density plot– shows the electron density determined eithercrystallographicallyor usingquantum mechanicsrather than distinct atoms or bonds.

|

|

- Ball and stick– atomic nuclei are represented by spheres (balls) and the bonds as sticks.

|

|

|

|

- Spacefilling modelsorCPK models(also anatomic coloring schemein representations) – the molecule is represented by overlapping spheres representing the atoms.

|

|

|

|

- Cartoon– a representation used for proteins where loops, beta sheets, and alpha helices are represented diagrammatically and no atoms or bonds are explicitly represented (e.g. the protein backbone is represented as a smooth pipe).

|

|

|

|

The greater the amount of lone pairs contained in a molecule, the smaller the angles between the atoms of that molecule. TheVSEPR theorypredicts that lone pairs repel each other, thus pushing the different atoms away from them.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^McMurry, John E.(1992),Organic Chemistry(3rd ed.), Belmont: Wadsworth,ISBN0-534-16218-5

- ^Cotton, F. Albert;Wilkinson, Geoffrey;Murillo, Carlos A.; Bochmann, Manfred (1999),Advanced Inorganic Chemistry(6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience,ISBN0-471-19957-5

- ^Alexandros Chremos; Jack F. Douglas (2015)."When does a branched polymer become a particle?".J. Chem. Phys.143(11): 111104.Bibcode:2015JChPh.143k1104C.doi:10.1063/1.4931483.PMID26395679.

- ^FRET descriptionArchived2008-09-18 at theWayback Machine

- ^Hillisch, A; Lorenz, M; Diekmann, S (2001). "Recent advances in FRET: distance determination in protein–DNA complexes".Current Opinion in Structural Biology.11(2): 201–207.doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00190-1.PMID11297928.

- ^FRET imaging introductionArchived2008-10-14 at theWayback Machine

- ^obtaining dihedral angles from3J coupling constantsArchived2008-12-07 at theWayback Machine

- ^Another Javascript-like NMR coupling constant to dihedralArchived2005-12-28 at theWayback Machine

- ^Miessler G.L. and Tarr D.A.Inorganic Chemistry(2nd ed., Prentice-Hall 1999), pp.57-58

- ^Haynes, William M., ed. (2013).CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics(94th ed.).CRC Press.pp. 9–26.ISBN9781466571143.

- ^Hoy, AR; Bunker, PR (1979). "A precise solution of the rotation bending Schrödinger equation for a triatomic molecule with application to the water molecule".Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy.74(1): 1–8.Bibcode:1979JMoSp..74....1H.doi:10.1016/0022-2852(79)90019-5.

- ^"CCCBDB Experimental bond angles page 2".Archived fromthe originalon 2014-09-03.Retrieved2014-08-27.

External links

[edit]- Molecular Geometry & Polarity Tutorial3D visualization of molecules to determine polarity.

- Molecular Geometry using Crystals3D structure visualization of molecules using Crystallography.