Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina

| |

|---|---|

| Anthem:Državna himna Bosne i Hercegovine Државна химна Босне и Херцеговине "National Anthem of Bosnia and Herzegovina" | |

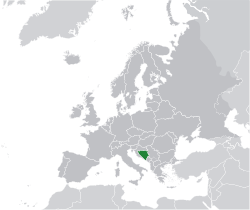

Location of Bosnia and Herzegovina (green) inEurope(dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Sarajevo[1] 43°52′N18°25′E/ 43.867°N 18.417°E |

| Official languages | |

| Writing system | |

| Ethnic groups (2013)[2] | |

| Religion (2013 census)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | [4][5][6] |

| Government | Federalparliamentary[6]directorial republic |

| Christian Schmidt[a] | |

| Denis Bećirović | |

| Željka Cvijanović Željko Komšić | |

| Borjana Krišto | |

| Legislature | Parliamentary Assembly |

| House of Peoples | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Establishment history | |

| 9th century | |

| 1154 | |

| 1377 | |

| 1463 | |

| 1878 | |

| 1 December 1918 | |

| 25 November 1943 | |

| 29 November 1945 | |

| 3 March 1992 | |

| 18 March 1994 | |

| 14 December 1995 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 51,209[7]km2(19,772 sq mi) (125th) |

• Water (%) | 1.4% |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | |

• 2013 census | 3,531,159[2] |

• Density | 69/km2(178.7/sq mi) (156th) |

| GDP(PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP(nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini(2015) | medium inequality |

| HDI(2022) | high(80th) |

| Currency | Convertible mark(BAM) |

| Time zone | UTC+01(CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+02(CEST) |

| Date format | d. m. yyyy. (CE) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +387 |

| ISO 3166 code | BA |

| Internet TLD | .ba |

| |

Bosnia and Herzegovina[a](Serbo-Croatian:Bosna i Hercegovina,Босна и Херцеговина),[b][c]sometimes known asBosnia-HerzegovinaandinformallyasBosnia,is a country inSoutheast Europe,situated on theBalkan Peninsula.It bordersSerbiato the east,Montenegroto the southeast, andCroatiato the north and southwest. In the south it has a 20 kilometres (12 miles) long coast on theAdriatic Sea,with the town ofNeumbeing its only access to the sea.Bosniahas a moderatecontinental climatewith hot summers and cold, snowy winters. In the central and eastern regions, the geography is mountainous, in the northwest it is moderately hilly, and in the northeast it is predominantly flat.Herzegovina,the smaller, southern region, has aMediterranean climateand is mostly mountainous.Sarajevois the capital and the largest city.

The area has been inhabited since at least theUpper Paleolithic,but evidence suggests that during theNeolithicage, permanent human settlements were established, including those that belonged to theButmir,Kakanj,andVučedolcultures. After the arrival of the firstIndo-Europeans,the area was populated by severalIllyrianandCelticcivilizations. Theancestorsof theSouth Slavicpeoples that populate the area today arrived during the 6th through the 9th century. In the 12th century, theBanate of Bosniawas established; by the 14th century, this had evolved into theKingdom of Bosnia.In the mid-15th century, it was annexed into theOttoman Empire,under whose rule it remaineduntil the late 19th century; the Ottomans broughtIslamto the region. From the late 19th century untilWorld War I,the country wasannexed into the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.In theinterwar period,Bosnia and Herzegovina was part of theKingdom of Yugoslavia.AfterWorld War II,it was granted full republic status in the newly formedSocialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.In 1992, following thebreakup of Yugoslavia,the republicproclaimed independence.This was followed by theBosnian War,which lasted until late 1995 and ended with the signing of theDayton Agreement.

The country is home to three mainethnic groups:Bosniaksare the largest group,Serbsthe second-largest, andCroatsthe third-largest. Minorities includeJews,Roma,Albanians, Montenegrins, Ukrainians and Turks.Bosnia and Herzegovina has abicamerallegislature and a three-memberpresidencymade up of one member from each of the three major ethnic groups. However, the central government's power is highly limited, as the country is largely decentralized. It comprises two autonomous entities—theFederation of Bosnia and HerzegovinaandRepublika Srpska—and a third unit, theBrčko District,which is governed by its own local government.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is adeveloping countryand ranks 74th in theHuman Development Index.Its economy is dominated by industry and agriculture, followed by tourism and the service sector. Tourism has increased significantly in recent years.[13][14]The country has a social-security and universal-healthcare system, and primary and secondary level education is free. It is a member of theUN,theOrganization for Security and Co-operation in Europe,theCouncil of Europe,thePartnership for Peace,and theCentral European Free Trade Agreement;it is also a founding member of theUnion for the Mediterranean,established in July 2008.[15]Bosnia and Herzegovina is anEU candidate countryand has also been a candidate forNATOmembership since April 2010.[16]

Etymology

The first preserved widely acknowledged mention of a form of the name "Bosnia"is inDe Administrando Imperio,a politico-geographical handbook written by theByzantine emperorConstantine VIIin the mid-10th century (between 948 and 952) describing the "small land" (χωρίονinGreek) of "Bosona" (Βοσώνα), where the Serbs dwell.[17]Bosnia was also mentioned in theDAI(χωριον βοσονα, small land of Bosnia), as a region of Baptized Serbia.[18][19]The section of the handbook is devoted to theSerbian prince's lands, and Bosnia is treated as a separate territory, though one that is particularly dependent on Serbs.[20]

The name of the land is believed to derive from the name of the riverBosnathat courses through the Bosnian heartland. According tophilologistAnton Mayer, the nameBosnacould derive fromIllyrian* "Bass-an-as", which in turn could derive from the Proto-Indo-European rootbʰegʷ-,meaning "the running water".[21]According to the English medievalistWilliam Miller,the Slavic settlers in Bosnia "adapted the Latin designation... Basante, to their own idiom by calling the stream Bosna and themselvesBosniaks".[22]

The nameHerzegovinameans "herzog's [land]", and "herzog" derives from the German word for "duke".[21]It originates from the title of a 15th-century Bosnian magnate,Stjepan Vukčić Kosača,who was "Herceg [Herzog] of Hum and the Coast" (1448).[23]Hum (formerly calledZachlumia) was an early medieval principality that had been conquered by the Bosnian Banate in the first half of the 14th century. When the Ottomans took over administration of the region, they called it theSanjak of Herzegovina(Hersek). It was included within theBosnia Eyaletuntil the formation of the short-livedHerzegovina Eyaletin the 1830s, which reemerged in the 1850s, after which the administrative region became commonly known asBosnia and Herzegovina.[24]

On initialproclamation of independence in 1992,the country's official name was theRepublic of Bosnia and Herzegovina,but following the 1995Dayton Agreementand the newconstitutionthat accompanied it, the official name was changed to Bosnia and Herzegovina.[25]

History

Early history

Bosnia has been inhabited by humans since at least thePaleolithic,as one of the oldest cave paintings was found inBadanj cave.Major Neolithic cultures such as theButmirandKakanjwere present along the riverBosnadated fromc. 6230 BCE–c. 4900 BCE.The bronze culture of theIllyrians,an ethnic group with a distinct culture and art form, started to organize itself in today'sSlovenia,Croatia,Bosnia and Herzegovina,Serbia,Kosovo,MontenegroandAlbania.[26]

From the 8th century BCE, Illyrian tribes evolved into kingdoms. The earliest recorded kingdom inIllyriawas the Enchele in the 8th century BCE. The Autariatae under Pleurias (337 BCE) were considered to have been a kingdom. The Kingdom of theArdiaei(originally a tribe from theNeretvavalley region) began at 230 BCE and ended at 167 BCE. The most notable Illyrian kingdoms and dynasties were those ofBardylis of the Dardaniand ofAgron of the Ardiaeiwho created the last and best-known Illyrian kingdom. Agron ruled over the Ardiaei and had extended his rule to other tribes as well.

From the 7th century BCE, bronze was replaced by iron, after which only jewelry and art objects were still made out of bronze. Illyrian tribes, under the influence ofHallstatt culturesto the north, formed regional centers that were slightly different. Parts of Central Bosnia were inhabited by theDaesitiatestribe, most commonly associated with theCentral Bosnian cultural group.The Iron AgeGlasinac-Mati cultureis associated with theAutariataetribe.

A very important role in their life was the cult of the dead, which is seen in their careful burials and burial ceremonies, as well as the richness of their burial sites. In northern parts, there was a long tradition of cremation and burial in shallow graves, while in the south the dead were buried in large stone or earthtumuli(natively calledgromile) that in Herzegovina were reaching monumental sizes, more than 50 m wide and 5 m high.Japodian tribeshad an affinity to decoration (heavy, oversized necklaces out of yellow, blue or white glass paste, and large bronzefibulas,as well as spiral bracelets, diadems and helmets out of bronze foil).

In the 4th century BCE, the first invasion ofCeltsis recorded. They brought the technique of thepottery wheel,new types of fibulas and different bronze and iron belts. They only passed on their way to Greece, so their influence in Bosnia and Herzegovina is negligible. Celtic migrations displaced manyIllyrian tribesfrom their former lands, but some Celtic and Illyrian tribes mixed. Concrete historical evidence for this period is scarce, but overall it appears the region was populated by a number of different peoples speaking distinct languages.

In theNeretva Deltain the south, there were importantHellenisticinfluences of the IllyrianDaorstribe. Their capital wasDaorsonin Ošanići nearStolac.Daorson, in the 4th century BCE, was surrounded bymegalithic,5 m high stonewalls (as large as those ofMycenaein Greece), composed of large trapezoid stone blocks. Daors made unique bronze coins and sculptures.

Conflict between the Illyrians andRomansstarted in 229 BCE, but Rome did not complete its annexation of the region until AD 9. It was precisely in modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina that Rome fought one of the most difficult battles in its history since thePunic Wars,as described by the Roman historianSuetonius.[27]This was the Roman campaign againstIllyricum,known asBellum Batonianum.[28]The conflict arose after an attempt to recruit Illyrians, and a revolt spanned for four years (6–9 AD), after which they were subdued.[29]In the Roman period, Latin-speaking settlers from the entireRoman Empiresettled among the Illyrians, and Roman soldiers were encouraged to retire in the region.[21]

Following the split of the Empire between 337 and 395 AD, Dalmatia and Pannonia became parts of theWestern Roman Empire.The region was conquered by theOstrogothsin 455 AD. It subsequently changed hands between theAlansand theHuns.By the 6th century, EmperorJustinian Ihad reconquered the area for theByzantine Empire.Slavs overwhelmed the Balkans in the 6th and 7th centuries. Illyrian cultural traits were adopted by the South Slavs, as evidenced in certain customs and traditions, placenames, etc.[30]

Middle Ages

TheEarly Slavsraided the Western Balkans, including Bosnia, in the 6th and early 7th century (amid theMigration Period), and were composed of small tribal units drawn from a single Slavic confederation known to the Byzantines as theSclaveni(whilst the relatedAntes,roughly speaking, colonized the eastern portions of the Balkans).[31][32] Tribes recorded by the ethnonyms of "Serb" and "Croat" are described as a second, latter, migration of different people during the second quarter of the 7th century who could or could not have been particularly numerous;[31][33][34]these early "Serb" and "Croat" tribes, whose exact identity is subject to scholarly debate,[34]came to predominate over the Slavs in the neighbouring regions. Croats "settled in area roughly corresponding to modern Croatia, and probably also including most of Bosnia proper, apart from the eastern strip of the Drina valley" while Serbs "corresponding to modern south-western Serbia (later known asRaška), and gradually extended their rule into the territories ofDukljaandHum".[35][36]

Bosnia is also believed to be first mentionedas a land (horion Bosona)in Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus'De Administrando Imperioin the mid 10th century, at the end of a chapter entitledOf the Serbs and the country in which they now dwell.[37]This has been scholarly interpreted in several ways and used especially by the Serb national ideologists to prove Bosnia as originally a "Serb" land.[37]Other scholars have asserted the inclusion of Bosnia in the chapter to merely be the result of Serbian Grand DukeČaslav's temporary rule over Bosnia at the time, while also pointing out Porphyrogenitus does not say anywhere explicitly that Bosnia is a "Serb land".[38]In fact, the very translation of the critical sentence where the wordBosona(Bosnia) appears is subject to varying interpretation.[37]In time, Bosnia formed a unit under its own ruler, who called himself Bosnian.[39]Bosnia, along with other territories, became part ofDukljain the 11th century, although it retained its own nobility and institutions.[40]

In theHigh Middle Ages,political circumstance led to the area being contested between theKingdom of Hungaryand the Byzantine Empire. Following another shift of power between the two in the early 12th century, Bosnia found itself outside the control of both and emerged as theBanate of Bosnia(under the rule of localbans).[21][41]The first Bosnian ban known by name wasBan Borić.[42]The second wasBan Kulin,whose rule marked the start of a controversy involving theBosnian Church– considered heretical by theRoman Catholic Church.In response to Hungarian attempts to use church politics regarding the issue as a way to reclaim sovereignty over Bosnia, Kulin held a council of local church leaders to renounce the heresy and embraced Catholicism in 1203. Despite this, Hungarian ambitions remained unchanged long after Kulin's death in 1204, waning only after an unsuccessful invasion in 1254. During this time, the population was calledDobriBošnjani( "Good Bosnians" ).[43][44]The names Serb and Croat, though occasionally appearing in peripheral areas, were not used in Bosnia proper.[45]

Bosnian history from then until the early 14th century was marked by a power struggle between theŠubićandKotromanićfamilies. This conflict came to an end in 1322, whenStephen II KotromanićbecameBan.By the time of his death in 1353, he was successful in annexing territories to the north and west, as well as Zahumlje and parts of Dalmatia. He was succeeded by his ambitious nephewTvrtkowho, following a prolonged struggle with nobility and inter-family strife, gained full control of the country in 1367. By the year 1377, Bosnia was elevated into a kingdom with the coronation of Tvrtko as the firstBosnian Kingin Mile nearVisokoin the Bosnian heartland.[46][47][48]

Following his death in 1391, however, Bosnia fell into a long period of decline. TheOttoman Empirehad started itsconquest of Europeand posed a major threat to theBalkansthroughout the first half of the 15th century. Finally, after decades of political and social instability, the Kingdom of Bosnia ceased to exist in 1463 after its conquest by the Ottoman Empire.[49]

There was a general awareness in medieval Bosnia, at least amongst the nobles, that they shared a joint state with Serbia and that they belonged to the same ethnic group. That awareness diminished over time, due to differences in political and social development, but it was kept in Herzegovina and parts of Bosnia which were a part of Serbian state.[50]

Ottoman Empire

TheOttoman conquest of Bosniamarked a new era in the country's history and introduced drastic changes in the political and cultural landscape. The Ottomans incorporated Bosnia as an integral province of the Ottoman Empire with its historical name and territorial integrity.[51]Within Bosnia, the Ottomans introduced a number of key changes in the territory's socio-political administration; including a new landholding system, a reorganization of administrative units, and a complex system of social differentiation by class and religious affiliation.[21]

Following Ottoman occupation, there was a steady flow of people out of Bosnia and a large number of abandoned villages in Bosnia are mentioned in the Ottoman registers,[52]while those who stayed eventually becameMuslims.Many Catholics in Bosnia fled to neighboring Catholic lands in the early Ottoman occupation.[53]The evidence indicates that the early Muslim conversions in Ottoman Bosnia in the 15th–16th century were among the locals who stayed rather than mass Muslim settlements from outside Bosnia.[54]In Herzegovina, manyOrthodoxpeople had also embraced Islam.[55]By the late 16th and early 17th century, Muslims are considered to have become an absolute majority in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Albanian Catholic priestPjetër Mazrekureported in 1624 that there were 450,000 Muslims, 150,000 Catholics and 75,000 Eastern Orthodox in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[56]

There was a lack ofOrthodox Churchactivity in Bosnia proper in the pre-Ottoman period.[57]An Orthodox Christian population in Bosnia was introduced as a direct result of Ottoman policy.[58]From the 15th century and onwards, Orthodox Christians (OrthodoxVlachsand non-Vlach Orthodox Serbs) from Serbia and other regions settled in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[59]Favored by the Ottomans over the Catholics, many Orthodox churches were allowed to be built in Bosnia by the Ottomans.[60][61]Quite a few Vlachs also became Islamized in Bosnia, and some (mainly in Croatia) became Catholics.[62]

The four centuries of Ottoman rule also had a drastic impact on Bosnia's population make-up, which changed several times as a result of the empire's conquests, frequent wars with European powers, forced and economic migrations, and epidemics. A native Slavic-speaking Muslim community emerged and eventually became the largest of the ethno-religious groups due to a lack of strong Christian church organizations and continuous rivalry between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, while the indigenousBosnian Churchdisappeared altogether (ostensibly by conversion of its members to Islam). The Ottomans referred to them askristianlarwhile the Orthodox and Catholics were calledgebirorkafir,meaning "unbeliever".[63]The BosnianFranciscans(and the Catholic population as a whole) were protected by official imperial decrees and in accordance and the full extent of Ottoman laws; however, in effect, these often merely affected arbitrary rule and behavior of powerful local elite.[21]

As the Ottoman Empire continued its rule in the Balkans (Rumelia), Bosnia was somewhat relieved of the pressures of being a frontier province and experienced a period of general welfare. A number of cities, such asSarajevoandMostar,were established and grew into regional centers of trade and urban culture and were then visited by Ottoman travelerEvliya Çelebiin 1648. Within these cities, various Ottoman Sultans financed the construction of many works ofBosnian architecturesuch as the country's first library in Sarajevo,madrassas,a school ofSufi philosophy,and a clock tower (Sahat Kula), bridges such as theStari Most,theEmperor's Mosqueand theGazi Husrev-beg Mosque.[64]

Furthermore, several Bosnian Muslims played influential roles in the Ottoman Empire's cultural andpolitical historyduring this time.[65]Bosnian recruits formed a large component of the Ottoman ranks in the battles ofMohácsandKrbava field,while numerous other Bosnians rose through the ranks of the Ottoman military to occupy the highest positions of power in the Empire, including admirals such asMatrakçı Nasuh;generals such asIsa-Beg Ishaković,Gazi Husrev-beg,Telli Hasan PashaandSarı Süleyman Pasha;administrators such asFerhad Pasha SokolovićandOsman Gradaščević;and GrandVizierssuch as the influentialSokollu Mehmed PashaandDamat Ibrahim Pasha.Some Bosnians emerged asSufimystics, scholars such asMuhamed Hevaji Uskufi Bosnevi,Ali Džabić;and poets in theTurkish,Albanian,Arabic,andPersian languages.[66]

However, by the late 17th century the Empire's military misfortunes caught up with the country, and the end of theGreat Turkish Warwith thetreaty of Karlowitzin 1699 again made Bosnia the Empire's westernmost province. The 18th century was marked by further military failures, numerous revolts within Bosnia, and several outbreaks of plague.[67]

The Porte's efforts at modernizing the Ottoman state were met with distrust growing to hostility in Bosnia, where local aristocrats stood to lose much through the proposedTanzimatreforms. This, combined with frustrations over territorial, political concessions in the north-east, and the plight ofSlavicMuslimrefugees arriving from theSanjak of SmederevointoBosnia Eyalet,culminated in a partially unsuccessful revolt byHusein Gradaščević,who endorsed a Bosnia Eyalet autonomous from the authoritarian rule of the Ottoman SultanMahmud II,who persecuted, executed and abolished theJanissariesand reduced the role of autonomousPashasin Rumelia. Mahmud II sent hisGrand vizierto subdue Bosnia Eyalet and succeeded only with the reluctant assistance ofAli Pasha Rizvanbegović.[66]Related rebellions were extinguished by 1850, but the situation continued to deteriorate.

New nationalist movements appeared in Bosnia by the middle of the 19th century. Shortly after Serbia's breakaway from the Ottoman Empire in the early 19th century, Serbian and Croatian nationalism rose up in Bosnia, and such nationalists made irredentist claims to Bosnia's territory. This trend continued to grow in the rest of the 19th and 20th centuries.[68]

Agrarian unrest eventually sparked theHerzegovinian rebellion,a widespread peasant uprising, in 1875. The conflict rapidly spread and came to involve several Balkan states and Great Powers, a situation that led to theCongress of Berlinand theTreaty of Berlinin 1878.[21]

Austria-Hungary

At the Congress ofBerlinin 1878, theAustro-HungarianForeign MinisterGyula Andrássyobtained the occupation and administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and he also obtained the right to station garrisons in theSanjak of Novi Pazar,which would remain underOttomanadministration until 1908, when the Austro-Hungarian troops withdrew from the Sanjak.

Although Austro-Hungarian officials quickly came to an agreement with the Bosnians, tensions remained and a mass emigration of Bosnians occurred.[21]However, a state of relative stability was reached soon enough and Austro-Hungarian authorities were able to embark on a number of social and administrative reforms they intended would make Bosnia and Herzegovina into a "model" colony.

Habsburg rulehad several key concerns in Bosnia. It tried to dissipate the South Slav nationalism by disputing the earlier Serb and Croat claims to Bosnia and encouraging identification of Bosnian orBosniakidentity.[69]Habsburg rule also tried to provide for modernisation by codifying laws, introducing new political institutions, establishing and expanding industries.[70]

Austria–Hungary began to plan the annexation of Bosnia, but due to international disputes the issue was not resolved until theannexation crisisof 1908.[71]Several external matters affected the status of Bosnia and its relationship with Austria–Hungary.A bloody coupoccurred in Serbia in 1903, which brought a radical anti-Austrian government into power inBelgrade.[72]Then in 1908, the revolt in the Ottoman Empire raised concerns that theIstanbulgovernment might seek the outright return of Bosnia and Herzegovina. These factors caused the Austro-Hungarian government to seek a permanent resolution of the Bosnian question sooner, rather than later.

Taking advantage of turmoil in the Ottoman Empire, Austro-Hungarian diplomacy tried to obtain provisional Russian approval for changes over the status of Bosnia and Herzegovina and published the annexation proclamation on 6 October 1908.[73]Despite international objections to the Austro-Hungarian annexation, Russians and their client state, Serbia, were compelled to accept the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in March 1909.

In 1910, Habsburg EmperorFranz Josephproclaimed the first constitution in Bosnia, which led to relaxation of earlier laws, elections and formation of theBosnian parliamentand growth of new political life.[74]

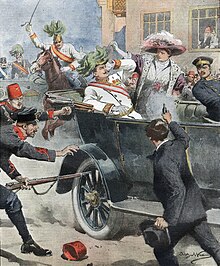

On 28 June 1914,Gavrilo Princip,aBosnian Serbmember of the revolutionary movementYoung Bosnia,assassinatedthe heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne,Archduke Franz Ferdinand,in Sarajevo—an event that was the spark that set offWorld War I.At the end of the war, theBosniakshad lost more men per capita than any other ethnic group in the Habsburg Empire whilst serving in theBosnian-Herzegovinian Infantry(known asBosniaken) of theAustro-Hungarian Army.[75]Nonetheless, Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole managed to escape the conflict relatively unscathed.[65]

The Austro-Hungarian authorities established an auxiliary militia known as theSchutzkorpswith a moot role in the empire's policy ofanti-Serbrepression.[76]Schutzkorps, predominantly recruited among the Muslim (Bosniak) population, were tasked with hunting down rebel Serbs (theChetniksandKomitadji)[77]and became known for their persecution ofSerbsparticularly in Serb populated areas of eastern Bosnia, where they partly retaliated against Serbian Chetniks who in fall 1914 had carried out attacks against the Muslim population in the area.[78][79]The proceedings of the Austro-Hungarian authorities led to around 5,500 citizens of Serb ethnicity in Bosnia and Herzegovina being arrested, and between 700 and 2,200 died in prison while 460 were executed.[77]Around 5,200 Serb families were forcibly expelled from Bosnia and Herzegovina.[77]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Following World War I, Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the South SlavKingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes(soon renamed Yugoslavia). Political life in Bosnia and Herzegovina at this time was marked by two major trends: social and economic unrest overproperty redistributionand the formation of several political parties that frequently changed coalitions and alliances with parties in other Yugoslav regions.[65]

The dominant ideological conflict of the Yugoslav state, between Croatian regionalism and Serbian centralization, was approached differently by Bosnia and Herzegovina's majorethnic groupsand was dependent on the overall political atmosphere.[21]The political reforms brought about in the newly established Yugoslavian kingdom saw few benefits for the Bosnian Muslims; according to the 1910 final census of land ownership and population according to religious affiliation conducted in Austria-Hungary, Muslims owned 91.1%, Orthodox Serbs owned 6.0%, Croat Catholics owned 2.6% and others, 0.3% of the property. Following the reforms, Bosnian Muslims were dispossessed of a total of 1,175,305 hectares of agricultural and forest land.[80]

Although the initial split of the country into 33oblastserased the presence of traditional geographic entities from the map, the efforts of Bosnian politicians, such asMehmed Spaho,ensured the six oblasts carved up from Bosnia and Herzegovina corresponded to the six sanjaks from Ottoman times and, thus, matched the country's traditional boundary as a whole.[21]

The establishment of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929, however, brought the redrawing of administrative regions intobanatesorbanovinasthat purposely avoided all historical and ethnic lines, removing any trace of a Bosnian entity.[21]Serbo-Croat tensions over the structuring of the Yugoslav state continued, with the concept of a separate Bosnian division receiving little or no consideration.

TheCvetković-Maček Agreementthat created theCroatian banatein 1939 encouraged what was essentially apartition of Bosnia and Herzegovinabetween Croatia and Serbia.[66]However the rising threat ofAdolf Hitler'sNazi Germanyforced Yugoslav politicians to shift their attention. Following a period that saw attempts at appeasement, the signing of theTripartite Treaty,and acoup d'état,Yugoslavia was finally invaded by Germany on 6 April 1941.[21]

World War II (1941–45)

Once the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was conquered by German forces inWorld War II,all of Bosnia and Herzegovina was ceded to the Nazi puppet regime, theIndependent State of Croatia(NDH) led by theUstaše.The NDH leaders embarked on acampaign of exterminationof Serbs, Jews,Romanias well as dissident Croats, and, later,Josip Broz Tito'sPartisansby setting up a number ofdeath camps.[81]The regime systematically and brutally massacred Serbs in villages in the countryside, using a variety of tools.[82]The scale of the violence meant that approximately every sixth Serb living in Bosnia and Herzegovina was the victim of a massacre and virtually every Serb had a family member that was killed in the war, mostly by the Ustaše. The experience had a profound impact in the collective memory of Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[83]An estimated 209,000 Serbs or 16.9% of its Bosnia population were killed on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war.[84]

The Ustaše recognized both Catholicism and Islam as the national religions, but held the positionEastern Orthodox Church,as a symbol of Serb identity, was their greatest foe.[85]Although Croats were by far the largest ethnic group to constitute the Ustaše, the Vice President of the NDH and leader of the Yugoslav Muslim OrganizationDžafer Kulenovićwas a Muslim, and Muslims in total constituted nearly 12% of the Ustaše military and civil service authority.[86]

Many Serbs themselves took up arms and joined the Chetniks, a Serb nationalist movement with the aim of establishing an ethnically homogeneous 'Greater Serbian' state[87]within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The Chetniks, in turn, pursued agenocidal campaignagainst ethnic Muslims and Croats, as well as persecuting a large number ofcommunistSerbs and other Communist sympathizers, with the Muslim populations of Bosnia, Herzegovina andSandžakbeing a primary target.[88]Once captured, Muslim villagers were systematically massacred by the Chetniks.[89]Of the 75,000 Muslims who died in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war,[90]approximately 30,000 (mostly civilians) were killed by the Chetniks.[91]Massacres against Croats were smaller in scale but similar in action.[92]Between 64,000 and 79,000 Bosnian Croats were killed between April 1941 to May 1945.[90]Of these, about 18,000 were killed by the Chetniks.[91]

A percentage of Muslims served in NaziWaffen-SSunits.[93]These units were responsible for massacres of Serbs in northwest and eastern Bosnia, most notably inVlasenica.[94]On 12 October 1941, a group of 108 prominent Sarajevan Muslims signed theResolution of Sarajevo Muslimsby which they condemned the persecution of Serbs organized by the Ustaše, made distinction between Muslims who participated in such persecutions and the Muslim population as a whole, presented information about the persecutions of Muslims by Serbs, and requested security for all citizens of the country, regardless of their identity.[95]

Starting in 1941, Yugoslav communists under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito organized their own multi-ethnic resistance group, the Partisans, who fought against bothAxisand Chetnik forces. On 29 November 1943, theAnti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia(AVNOJ) with Tito at its helm held a founding conference inJajcewhere Bosnia and Herzegovina was reestablished as a republic within the Yugoslavian federation in its Habsburg borders.[96]During the entire course ofWorld War II in Yugoslavia,64.1% of all Bosnian Partisans were Serbs, 23% were Muslims and 8.8% Croats.[97]

Military success eventually prompted theAlliesto support the Partisans, resulting in the successfulMaclean Mission,but Tito declined their offer to help and relied on his own forces instead. All the major military offensives by the antifascist movement of Yugoslavia against Nazis and their local supporters were conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina and its peoples bore the brunt of the fighting. More than 300,000 people died in Bosnia and Herzegovina in World War II, or more than 10% of the population.[98]At the end of the war, the establishment of theSocialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia,with theconstitution of 1946,officially made Bosnia and Herzegovina one of six constituent republics in the new state.[21]

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1992)

Due to its central geographic position within the Yugoslavian federation, post-war Bosnia was selected as a base for the development of the military defense industry. This contributed to a large concentration of arms and military personnel in Bosnia; a significant factor inthe war that followed the break-up of Yugoslaviain the 1990s.[21]However, Bosnia's existence within Yugoslavia, for the large part, was relatively peaceful and very prosperous, with high employment, a strong industrial and export oriented economy, a good education system and social and medical security for every citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Several international corporations operated in Bosnia—Volkswagenas part of TAS (car factory in Sarajevo, from 1972),Coca-Cola(from 1975), SKF Sweden (from 1967),Marlboro(a tobacco factory in Sarajevo), andHoliday Innhotels. Sarajevo was the site of the1984 Winter Olympics.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Bosnia was a political backwater of Yugoslavia. In the 1970s, a strong Bosnian political elite arose, fueled in part by Tito's leadership in theNon-Aligned Movementand Bosnians serving in Yugoslavia's diplomatic corps. While working within the Socialist system, politicians such asDžemal Bijedić,Branko MikulićandHamdija Pozderacreinforced and protected the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[99]Their efforts proved key during the turbulent period following Tito's death in 1980, and are today considered some of the early steps towardsBosnian independence.However, the republic did not escape the increasingly nationalistic climate of the time. With the fall of communism and the start of thebreakup of Yugoslavia,doctrine of tolerance began to lose its potency, creating an opportunity for nationalist elements in the society to spread their influence.[100]

Bosnian War (1992–1995)

On 18 November 1990,multi-party parliamentary electionswere held throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina. A second round followed on 25 November, resulting in anational assemblywhere communist power was replaced by a coalition of three ethnically based parties.[101]FollowingSloveniaandCroatia's declarations of independence from Yugoslavia, a significant split developed among the residents of Bosnia and Herzegovina on the issue of whether to remain within Yugoslavia (overwhelmingly favored by Serbs) or seek independence (overwhelmingly favored by Bosniaks and Croats).[102]

The Serb members of parliament, consisting mainly of theSerb Democratic Partymembers, abandoned the central parliament in Sarajevo, and formed theAssembly of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovinaon 24 October 1991, which marked the end of the three-ethnic coalition that governed after the elections in 1990. This Assembly established the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina in part of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 9 January 1992. It was renamedRepublika Srpskain August 1992. On 18 November 1991, the party branch in Bosnia and Herzegovina of the ruling party in the Republic of Croatia, theCroatian Democratic Union(HDZ), proclaimed the existence of theCroatian Community of Herzeg-Bosniain a separate part of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina with theCroatian Defence Council(HVO) as its military branch.[103]It went unrecognized by theGovernment of Bosnia and Herzegovina,which declared it illegal.[104][105]

A declaration of the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 15 October 1991 was followed by areferendum for independenceon 29 February and 1 March 1992, which was boycotted by the great majority of Serbs. The turnout in the independence referendum was 63.4 percent and 99.7 percent of voters voted for independence.[106]Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on 3 March 1992 and received international recognition the following month on 6 April 1992.[107]TheRepublic of Bosnia and Herzegovinawas admitted as a member state of theUnited Nationson 22 May 1992.[108]Serbian leaderSlobodan Miloševićand Croatian leaderFranjo Tuđmanare believed to have agreed on apartition of Bosnia and Herzegovinain March 1991, with the aim of establishingGreater SerbiaandGreater Croatia.[109]

Following Bosnia and Herzegovina's declaration of independence, Bosnian Serb militias mobilized in different parts of the country. Government forces were poorly equipped and unprepared for the war.[110]International recognition of Bosnia and Herzegovina increased diplomatic pressure for theYugoslav People's Army(JNA) to withdraw from the republic's territory, which they officially did in June 1992. The Bosnian Serb members of the JNA simply changed insignia, formed theArmy of Republika Srpska(VRS), and continued fighting. Armed and equipped from JNA stockpiles in Bosnia, supported by volunteers and various paramilitary forces from Serbia, and receiving extensive humanitarian, logistical and financial support from theFederal Republic of Yugoslavia,Republika Srpska's offensives in 1992 managed to place much of the country under its control.[21]The Bosnian Serb advance was accompanied by theethnic cleansingof Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats from VRS-controlled areas. Dozens of concentration camps were established in which inmates were subjected to violence and abuse, including rape.[111]The ethnic cleansing culminated in theSrebrenica massacreof more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys in July 1995, which was ruled to have been agenocideby theInternational Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia(ICTY).[112]Bosniak and Bosnian Croat forces also committed war crimes against civilians from different ethnic groups, though on a smaller scale.[113][114][115][116]Most of the Bosniak and Croat atrocities were committed during theCroat–Bosniak War,a sub-conflict of the Bosnian War that pitted theArmy of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina(ARBiH) against the HVO. The Bosniak-Croat conflict ended in March 1994, with the signing of theWashington Agreement,leading to the creation of a joint Bosniak-CroatFederation of Bosnia and Herzegovina,which amalgamated HVO-held territory with that held by theArmy of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina(ARBiH).[117]

Recent history

On 4 February 2014, theprotestsagainst theGovernment of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina,one of the country's two entities, dubbed the Bosnian Spring, the name being taken from theArab Spring,began in the northern town ofTuzla.Workers from several factories that had been privatised and gone bankrupt assembled to demand action over jobs, unpaid salaries and pensions.[118]Soon protests spread to the rest of the Federation, with violent clashes reported in close to 20 towns, the biggest of which wereSarajevo,Zenica,Mostar,Bihać,Brčkoand Tuzla.[119]The Bosnian news media reported that hundreds of people had been injured during the protests, including dozens of police officers, with bursts of violence in Sarajevo, in the northern city of Tuzla, in Mostar in the south, and in Zenica in central Bosnia. The same level of unrest or activism did not occur in Republika Srpska, but hundreds of people also gathered in support of protests in the city ofBanja Lukaagainst its separate government.[120][121][122]

The protests marked the largest outbreak of public anger over high unemployment and two decades of political inertia in the country since the end of the Bosnian War in 1995.[123]

According to a report made byChristian Schmidtof theOffice of High Representativein late 2021, Bosnia and Herzegovina has been experiencing intensified political and ethnic tensions, which could potentially break the country apart and slide it back into war once again.[124][125]TheEuropean Unionfears this will lead to furtherBalkanizationin the region.[126]

Geography

Bosnia and Herzegovina is in the westernBalkans,borderingCroatia(932 km or 579 mi) to the north and west,Serbia(302 km or 188 mi) to the east, andMontenegro(225 km or 140 mi) to the southeast. It has a coastline about 20 kilometres (12 miles) long surrounding the town ofNeum.[127][128]It lies between latitudes42°and46° N,and longitudes15°and20° E.

The country's name comes from the two alleged regionsBosniaandHerzegovina,whose border was never defined. Historically, Bosnia's official name never included any of its many regions until the Austro-Hungarian occupation.

The country is mostly mountainous, encompassing the centralDinaric Alps.The northeastern parts reach into thePannonian Basin,while in the south it borders theAdriatic.The Dinaric Alps generally run in a southeast–northwest direction, and get higher towards the south. The highest point of the country is the peak ofMaglićat 2,386 metres (7,828.1 feet), on the Montenegrin border. Other major mountains includeVolujak,Zelengora,Lelija,Lebršnik,Orjen,Kozara,Grmeč,Čvrsnica,Prenj,Vran,Vranica,Velež,Vlašić,Cincar,Romanija,Jahorina,Bjelašnica,TreskavicaandTrebević.The geological composition of the Dinaric chain of mountains in Bosnia consists primarily oflimestone(includingMesozoiclimestone), with deposits ofiron,coal,zinc,manganese,bauxite,lead,andsaltpresent in some areas, especially in central and northern Bosnia.[129]

Overall, nearly 50% of Bosnia and Herzegovina is forested. Most forest areas are in the centre, east and west parts of Bosnia. Herzegovina has a drier Mediterranean climate, with dominantkarsttopography. Northern Bosnia (Posavina) contains very fertile agricultural land along theSavariver and the corresponding area is heavily farmed. This farmland is a part of the Pannonian Plain stretching into neighboring Croatia and Serbia. The country has only 20 kilometres (12 miles) of coastline,[127][130]around the town of Neum in theHerzegovina-Neretva Canton.Although the city is surrounded by Croatian peninsulas, by international law, Bosnia and Herzegovina has aright of passageto the outer sea.

Sarajevois the capital[1]and largest city.[6]Other major cities includeBanja LukaandPrijedorin the northwest region known asBosanska Krajina,Tuzla,Bijeljina,DobojandBrčkoin the northeast,Zenicain the central part of the country, andMostar,the largest city in the southern region ofHerzegovina.

There are seven major rivers in Bosnia and Herzegovina:[131]

- TheSavais the largest river of the country, and forms its northernnatural borderwith Croatia. It drains 76%[131]of the country's territory into theDanubeand then theBlack Sea.Bosnia and Herzegovina is a member of theInternational Commission for the Protection of the Danube River(ICPDR).

- TheUna,SanaandVrbasare right tributaries of the Sava. They are in the northwestern region ofBosanska Krajina.

- TheBosnariver gave its name to the country, and is the longest river fully contained within it. It stretches through central Bosnia, from its source nearSarajevoto Sava in the north.

- TheDrinaflows through the eastern part of Bosnia, and for the most part it forms a natural border with Serbia.

- TheNeretvais the major river of Herzegovina and the only major river that flows south, into the Adriatic Sea.

Biodiversity

Phytogeographically,Bosnia and Herzegovina belongs to theBoreal Kingdomand is shared between the Illyrian province of theCircumboreal Regionand Adriatic province of theMediterranean Region.According to theWorld Wide Fund for Nature(WWF), the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina can be subdivided into fourecoregions:Balkan mixed forests,Dinaric Mountains mixed forests,Pannonian mixed forestsandIllyrian deciduous forests.[132]The country had a 2018Forest Landscape Integrity Indexmean score of 5.99/10, ranking it 89th globally out of 172 countries.[133]In Bosnia and Herzegovinaforest coveris around 43% of the total land area, equivalent to 2,187,910 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, down from 2,210,000 hectares (ha) in 1990. For the year 2015, 74% of the forest area was reported to be underpublic ownershipand 26%private ownership.[134][135]

Politics

Government

As a result of theDayton Agreement,the civilian peace implementation is supervised by theHigh Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovinaselected by thePeace Implementation Council(PIC). The High Representative is the highest political authority in the country. The High Representative has many governmental and legislative powers, including the dismissal of elected and non-elected officials. Due to the vast powers of the High Representative overBosnian politicsand essentialvetopowers, the position has also been compared to that of aviceroy.[136][137][138][139]

Politics take place in a framework of aparliamentaryrepresentative democracy,wherebyexecutive poweris exercised by theCouncil of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina.Legislative poweris vested in both the Council of Ministers and theParliamentary Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina.Members of the Parliamentary Assembly are chosen according to aproportional representation(PR) system.[140][141]

Bosnia and Herzegovina is aliberal democracy.[clarification needed]It has several levels of political structuring, according to theDayton Agreement.The most important of these levels is the division of the country into two entities: theFederation of Bosnia and HerzegovinaandRepublika Srpska.The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina covers 51% of Bosnia and Herzegovina's total area, while Republika Srpska covers 49%. The entities, based largely on the territories held by the two warring sides at the time, were formally established by the Dayton Agreement in 1995 because of the tremendous changes in Bosnia and Herzegovina's ethnic structure. At the national level, there exists only a finite set of exclusive or joint competencies, whereas the majority of authority rests within the entities.[142]Sumantra Bosedescribes Bosnia and Herzegovina as a consociationalconfederation.[143]

TheBrčko Districtin the north of the country was created in 2000, out of land from both entities. It officially belongs to both, but is governed by neither, and functions under a decentralized system of local government. For election purposes, Brčko District voters can choose to participate in either the Federation or Republika Srpska elections. The Brčko District has been praised for maintaining a multiethnic population and a level of prosperity significantly above the national average.[144]

The third level of Bosnia and Herzegovina's political subdivision is manifested incantons.They are unique to the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina entity, which consists of ten of them. Each has a cantonal government, which is under the law of the Federation as a whole. Some cantons are ethnically mixed and have special laws to ensure the equality of all constituent people.[145]

The fourth level of political division in Bosnia and Herzegovina are themunicipalities.The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is divided into 79 municipalities, and Republika Srpska into 64. Municipalities also have their own local government, and are typically based on the most significant city or place in their territory. As such, many municipalities have a long tradition and history with their present boundaries. Some others, however, were only created following the recent war after traditional municipalities were split by theInter-Entity Boundary Line.Each canton in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of several municipalities, which are divided into local communities.[146]

Besides entities, cantons, and municipalities, Bosnia and Herzegovina also has four "official" cities. These are:Banja Luka,Mostar,SarajevoandEast Sarajevo.The territory and government of the cities of Banja Luka and Mostar corresponds to the municipalities of the same name, while the cities of Sarajevo and East Sarajevo officially consist of several municipalities. Cities have their own city government whose power is in between that of the municipalities and cantons (or the entity, in the case of Republika Srpska).

More recently, several central institutions have been established (such as adefense ministry,security ministry, state court,indirect taxationservice and so on) in the process of transferring part of the jurisdiction from the entities to the state. The representation of the government of Bosnia and Herzegovina is by elites who represent the country's three major groups, with each having a guaranteed share of power.

TheChairof thePresidency of Bosnia and Herzegovinarotates among three members (Bosniak,Serb,Croat), each elected as the chair for an eight-month term within their four-year term as a member. The three members of the Presidency are elected directly by the people, with Federation voters voting for the Bosniak and the Croat and the Republika Srpska voters voting for the Serb.

TheChair of the Council of Ministersis nominated by the Presidency and approved by the parliamentaryHouse of Representatives.The Chair of the Council of Ministers is then responsible for appointing a Foreign Minister, Minister of Foreign Trade and others as appropriate.

The Parliamentary Assembly is the lawmaking body in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It consists of two houses: theHouse of Peoplesand the House of Representatives. The House of Peoples has 15 delegates chosen by parliaments of the entities, two-thirds of which come from the Federation (5 Bosniaks and 5 Croats) and one-third from the Republika Srpska (5 Serbs). The House of Representatives is composed of 42 Members elected by the people under a form of proportional representation, two-thirds elected from the Federation and one-third elected from Republika Srpska.[147]

TheConstitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovinais the supreme, final arbiter of legal matters. It is composed of nine members: four members are selected by theFederal House of Representatives,two by theNational Assembly of Republika Srpskaand three by the President of theEuropean Court of Human Rightsafter consultation with the Presidency, who cannot be Bosnian citizens.[148]

However, the highest political authority in the country is the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina, the chiefexecutive officerfor the international civilian presence in the country and is selected by theEuropean Union.Since 1995, the High Representative has been able to bypass the elected parliamentary assembly, and since 1997 has been able to remove elected officials. The methods selected by the High Representative have been criticized as undemocratic.[149]International supervisionis to end when the country is deemed politically and democratically stable and self-sustaining.

Military

Bosnian Ground Forces Combined Resolve XV |

Bosnian Air Force TH-1H Hueymain transport aircraft |

TheArmed Forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina(OSBiH) were unified into a single entity in 2005, with the merger of theArmy of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovinaand theArmy of Republika Srpska,which had defended their respective regions.[150]TheMinistry of Defencewas formed in 2004.[151]

The Bosnian military consists of theBosnian Ground ForcesandAir Force and Air Defense.[152]The Ground Forces number 7,200 active and 5,000 reserve personnel.[153]They are armed with a mix of American, Yugoslavian, Soviet, and European-made weaponry, vehicles, and military equipment. The Air Force and Air Defense Forces have 1,500 personnel and about 62 aircraft. The Air Defense Forces operateMANPADShand-held missiles,surface-to-air missile(SAM) batteries, anti-aircraft cannons, and radar. The Army has recently adopted remodeledMARPATuniforms, used by Bosnian soldiers serving with theInternational Security Assistance Force(ISAF) inAfghanistan.A domestic production program is now underway to ensure that army units are equipped with the correct ammunition.[154]

Beginning in 2007, the Ministry of Defence undertook the army's first ever international assistance mission, enlisting the military to serve with ISAF peace missions to Afghanistan,Iraqand theDemocratic Republic of the Congoin 2007. Five officers, acting as officers/advisors, served in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. 45 soldiers, mostly acting as base security and medical assistants, served in Afghanistan. 85 Bosnian soldiers served as base security in Iraq, occasionally conducting infantry patrols there as well. All three deployed groups have been commended by their respective international forces as well as the Ministry of Defence of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The international assistance operations are still ongoing.[155]

The Air Force and Anti-Aircraft Defence of Bosnia and Herzegovina was formed when elements of the Army of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and theRepublika Srpska Air Forcewere merged in 2006. The Air Force has seen improvements in the last few years with added funds for aircraft repairs and improved cooperation with theGround Forcesas well as to the citizens of the country. The Ministry of Defence is pursuing the acquisition of new aircraft including helicopters and perhaps even fighter jets.[156]

Foreign relations

European Union integrationis one of the main political objectives of Bosnia and Herzegovina; it initiated theStabilisation and Association Processin 2007. Countries participating in the SAP have been offered the possibility to become, once they fulfill the necessary conditions, Member States of the EU. Bosnia and Herzegovina is therefore a potential candidate country for EU accession.[157]

The implementation of theDayton Agreementin 1995 has focused the efforts of policymakers in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as the international community, on regional stabilization in the countries-successors of theformer Yugoslavia.[158]

Within Bosnia and Herzegovina, relations with its neighbors ofCroatia,SerbiaandMontenegrohave been fairly stable since the signing of the Dayton Agreement. On 23 April 2010, Bosnia and Herzegovina received theMembership Action PlanfromNATO,which is the last step before full membership in the alliance. Full membership was initially expected in 2014 or 2015, depending on the progress of reforms.[159]In December 2018, NATO approved a Bosnian Membership Action Plan.[160]

Bosnia and Herzegovina is the 61st most peaceful country in the world, according to the 2024Global Peace Index.[161]

Demography

According to the1991 census,Bosnia and Herzegovina had a population of 4,369,319, while the 1996 World Bank Group census showed a decrease to 3,764,425.[162]Large population migrations during theYugoslav Warsin the 1990s have caused demographic shifts in the country. Between 1991 and 2013, political disagreements made it impossible to organize a census. A census had been planned for 2011,[163]and then for 2012,[164]but was delayed until October 2013. The2013 censusfound a total population of 3,531,159 people,[2]a drop of approximately 20% since 1991.[165]The 2013 census figures include non-permanent Bosnian residents and for this reason are contested by Republika Srpska officials and Serb politicians (see Ethnic groups below).[166]

Largest cities

Ethnic groups

Bosnia and Herzegovina is home to three ethnic "constituent peoples",namelyBosniaks,SerbsandCroats,plus a number of smaller groups includingJewsandRoma.[168]According to data from the 2013 census published by theAgency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina,Bosniaks constitute 50.1% of the population, Serbs 30.8%, Croats 15.5% and others 2.7%, with the remaining respondents not declaring their ethnicity or not answering.[2]The census results are contested by theRepublika Srpskastatistical office and byBosnian Serbpoliticians.[169]The dispute over the census concerns the inclusion of non-permanent Bosnian residents in the figures, which Republika Srpska officials oppose.[166]TheEuropean Union's statistics office,Eurostat,concluded in May 2016 that the census methodology used by the Bosnian statistical agency is in line with international recommendations.[170]

Languages

Bosnia's constitution does not specify any official languages.[171][172][173]However, academics Hilary Footitt and Michael Kelly note theDayton Agreementstates it[clarification needed]is "done inBosnian,Croatian,English andSerbian",and they describe this as the" de facto recognition of three official languages "at the state level. The equal status of Bosnian, Serbian and Croatian was verified by theConstitutional Courtin 2000.[173]It ruled the provisions of theFederationand Republika Srpska constitutions on language were incompatible with the state constitution, since they only recognised Bosnian and Croatian (in the case of the Federation) and Serbian (in the case of Republika Srpska) as official languages at the entity level. As a result, the wording of the entity constitutions was changed and all three languages were made official in both entities.[173]The threestandard languagesare fullymutually intelligibleand are known collectively under the appellation ofSerbo-Croatian,despite this term not being formally recognized in the country. Use of one of the three languages has become a marker of ethnic identity.[174]Michael Kelly and Catherine Baker argue: "The three official languages of today's Bosnian state...represent the symbolic assertion of national identity over the pragmatism of mutual intelligibility".[175]

According to the 1992European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages(ECRML), Bosnia and Herzegovina recognizes the following minority languages:Albanian,Montenegrin,Czech,Italian,Hungarian,Macedonian,German,Polish,Romani,Romanian,Rusyn,Slovak,Slovene,Turkish,Ukrainianand Jewish (YiddishandLadino).[176]The German minority in Bosnia and Herzegovina are mostly remnants ofDonauschwaben(Danube Swabians), who settled in the area after theHabsburg monarchyclaimed the Balkans from theOttoman Empire.Due toexpulsionsand(forced) assimilationafter the twoWorld wars,the number of ethnic Germans in Bosnia and Herzegovina was drastically diminished.[177]

In the 2013 census, 52.86% of the population consider their mother tongue Bosnian, 30.76% Serbian, 14.6% Croatian and 1.57% another language, with 0.21% not giving an answer.[2]

Religion

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a religiously diverse country. According to the 2013 census,Muslimscomprised 50.7% of the population, whileOrthodox Christiansmade 30.7%,Catholic Christians15.2%, 1.2% other and 1.1%atheistoragnostic,with the remainder not declaring or not answering the question.[2]A 2012 survey found 54% of Bosnia's Muslims werenon-denominational,while 38% followedSunnism.[178]

Urban areas

Sarajevois home to 419,957 inhabitants in its urban area which comprises theCity of Sarajevoas well as the municipalities ofIlidža,Vogošća,Istočna Ilidža,Istočno Novo SarajevoandIstočni Stari Grad.[179]Themetro areahas a population of 555,210 and includesSarajevo Canton,East Sarajevoand the municipalities ofBreza,Kiseljak,KreševoandVisoko.[180]

Economy

During theBosnian War,the economy suffered €200 billion in material damages, roughly €326.38 billion in 2022 (inflation adjusted).[181][182]Bosnia and Herzegovina faces the dual-problem of rebuilding a war-torn country and introducing transitional liberal market reforms to its formerly mixed economy. One legacy of the previous era is a strong industry; under former republic presidentDžemal BijedićandYugoslavPresidentJosip Broz Tito,metal industries were promoted in the republic, resulting in the development of a large share of Yugoslavia's plants;SR Bosnia and Herzegovinahad a very strong industrial export oriented economy in the 1970s and 1980s, with large scale exports worth millions ofUS$.

For most of Bosnia's history, agriculture has been conducted on privately owned farms; Fresh food has traditionally been exported from the republic.[183]

The war in the 1990s, caused a dramatic change in the Bosnian economy.[184]GDP fell by 60% and the destruction of physical infrastructure devastated the economy.[185]With much of the production capacity unrestored, the Bosnian economy still faces considerable difficulties. Figures show GDP and per capita income increased 10% from 2003 to 2004; this and Bosnia's shrinkingnational debtbeing negative trends, and high unemployment 38.7% and a largetrade deficitremain cause for concern.

The national currency is the (Euro-pegged)convertible mark(KM), controlled by thecurrency board.Annual inflation is the lowest relative to other countries in the region at 1.9% in 2004.[186]The international debt was $5.1 billion (as of 31 December 2014).Real GDPgrowth rate was 5% for 2004 according to theCentral Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovinaand Statistical Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Bosnia and Herzegovina has displayed positive progress in the previous years, which decisively moved its place from the lowest income equality rank ofincome equality rankingsfourteen out of 193 nations.[187]

According toEurostatdata, Bosnia and Herzegovina's PPS GDP per capita stood at 29 per cent of the EU average in 2010.[188]

TheInternational Monetary Fund(IMF) announced a loan to Bosnia worth US$500 million to be delivered byStand-By Arrangement.This was scheduled to be approved in September 2012.[189]

TheUnited States EmbassyinSarajevoproduces the Country Commercial Guide – an annual report that delivers a comprehensive look at Bosnia and Herzegovina's commercial and economic environment, using economic, political, and market analysis.

By some estimates,grey economyis 25.5% of GDP.[190]

In 2017, exports grew by 17% when compared to the previous year, totaling €5.65 billion.[191]The total volume offoreign tradein 2017 amounted to €14.97 billion and increased by 14% compared to the previous year. Imports of goods increased by 12% and amounted to €9.32 billion. Thecoverage of imports by exportsincreased by 3% compared to the previous year and now it is 61 percent. In 2017, Bosnia and Herzegovina mostly exportedcar seats,electricity,processed wood,aluminiumandfurniture.In the same year, it mostly importedcrude oil,automobiles,motor oil,coalandbriquettes.[192]

The unemployment rate in 2017 was 20.5%, butThe Vienna Institute for International Economic Studiesis predicting falling unemployment rate for the next few years. In 2018, the unemployment should be 19.4% and it should further fall to 18.8% in 2019. In 2020, the unemployment rate should go down to 18.3%.[193]

On 31 December 2017, theCouncil of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovinaissued the report on public debt of Bosnia and Herzegovina, stating the public debt was reduced by €389.97 million, or by more than 6% when compared to 31 December 2016. By the end of 2017, public debt was €5.92 billion, which amounted to 35.6 percent of GDP.[194]

As of 31 December 2017[update],there were 32,292 registered companies in the country, which together had revenues of €33.572 billion that same year.[195]

In 2017, the country received €397.35 million inforeign direct investment,which equals to 2.5% of the GDP.[196]

In 2017, Bosnia and Herzegovina ranked third in the world in terms of the number of new jobs created by foreign investment, relative to the number of inhabitants.[197][198]

In 2018, Bosnia and Herzegovina exported goods worth 11.9 billion KM (€6.07 billion), which is 7.43% higher than in the same period in 2017, while imports amounted to 19.27 billion KM (€9.83 billion), which is 5.47% higher.[199]

The average price of new apartments sold in the country in the first six months of 2018 is 1,639 km (€886.31) per square metre. This represents a jump of 3.5% from the previous year.[200]

On 30 June 2018, public debt of Bosnia and Herzegovina amounted to about €6.04 billion, of which external debt is 70.56 percent, while the internal debt is 29.4 percent of total public indebtedness. The share of public debt in gross domestic product is 34.92 percent.[201]

In the first 7 months of 2018, 811,660 tourists visited the country, a 12.2% jump when compared to the first 7 months of 2017.[202]In the first 11 months of 2018, 1,378,542 tourists visited Bosnia-Herzegovina, an increase of 12.6%, and had 2,871,004 overnight hotel stays, a 13.8% increase from the previous year. Also, 71.8% of the tourists came from foreign countries.[203]In the first seven months of 2019, 906,788 tourists visited the country, an 11.7% jump from the previous year.[204]

In 2018, the total value ofmergers and acquisitionsin Bosnia and Herzegovina amounted to €404.6 million.[205]

In 2018, 99.5 percent of enterprises in Bosnia and Herzegovina used computers in their business, while 99.3 percent had internet connections, according to a survey conducted by the Bosnia and Herzegovina Statistics Agency.[206]

In 2018, Bosnia and Herzegovina received 783.4 million KM (€400.64 million) indirect foreign investment,which was equivalent to 2.3% of GDP.[207]

In 2018, the Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina made a profit of 8,430,875 km (€4,306,347).[208]

TheWorld Bankpredicted that the economy would grow 3.4% in 2019.[209]

Bosnia and Herzegovina was placed 83rd on theIndex of Economic Freedomfor 2019. The total rating for Bosnia and Herzegovina is 61.9. This position represents some progress relative to the 91st place in 2018. This result is below the regional level, but still above the global average, making Bosnia and Herzegovina a "moderately free" country.[210]

On 31 January 2019, total deposits in Bosnian banks were KM 21.9 billion (€11.20 billion), which represents 61.15% of nominal GDP.[211]

In the second quarter of 2019, the average price of new apartments sold in Bosnia and Herzegovina was 1,606 km (€821.47) per square metre.[212]

In the first six months of 2019, exports amounted to 5.829 billion KM (€2.98 billion), which is 0.1% less than in the same period of 2018, while imports amounted to 9.779 billion KM (€5.00 billion), which is by 4.5% more than in the same period of the previous year.[213]

In the first six months of 2019, foreign direct investment amounted to 650.1 million KM (€332.34 million).[214]

Bosnia and Herzegovina was ranked 77th in theGlobal Innovation Indexin 2023.[215]

As of 30 November 2023, Bosnia and Herzegovina had 1.3 million registered motor vehicles.[216]

Tourism

According to projections by theWorld Tourism Organization,Bosnia and Herzegovina had the third highest tourism growth rate in the world between 1995 and 2020.[217][218]

In 2017, 1,307,319 tourists visited Bosnia and Herzegovina, an increase of 13.7%, and had 2,677,125 overnight hotel stays, a 12.3% increase from the previous year. 71.5% of the tourists came from foreign countries.[219]

In 2018, 1.883.772 tourists visited Bosnia and Herzegovina, an increase of 44,1%, and had 3.843.484 overnight hotel stays, a 43.5% increase from the previous year. Also, 71.2% of the tourists came from foreign countries.[220]

In 2006, when ranking the best cities in the world,Lonely PlanetplacedSarajevo,thenational capital[1]and host of the1984 Winter Olympics,as #43 on the list.[221]Tourism in Sarajevo is chiefly focused on historical, religious, and cultural aspects. In 2010, Lonely Planet's "Best in Travel" nominated it as one of the top ten cities to visit that year.[222]Sarajevo also won travel blog Foxnomad's "Best City to Visit" competition in 2012, beating more than one hundred other cities around the entire world.[223]

Međugorjehas become one of the most popular pilgrimage sites forCatholicsfrom around the world and has turned into Europe's third most important religious place, where each year more than 1 million people visit.[224]It has been estimated that 30 million pilgrims have come to Međugorje since the reputed apparitions began in 1981.[225]Since 2019, pilgrimages to Međugorje have been officially authorized and organized by theVatican.[226]

Bosnia has also become an increasingly popular skiing andEcotourismdestination. The mountains that hosted the winter olympic games ofBjelašnica,JahorinaandIgmanare the most visited skiing mountains in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Bosnia and Herzegovina remains one of the last undiscovered natural regions of the southern area of theAlps,with vast tracts of wild and untouched nature attracting adventurers and nature lovers.National Geographicnamed Bosnia and Herzegovina as the best mountain biking adventure destination for 2012.[227]The centralBosnian Dinaric Alpsare favored by hikers and mountaineers, as they contain bothMediterraneanandAlpineclimates.Whitewater raftinghas become somewhat of anational pastimein Bosnia and Herzegovina.[228]The primary rivers used for whitewater rafting in the country include theVrbas,Tara,Drina,NeretvaandUna.[229]Meanwhile, the most prominent rivers are the Vrbas and Tara, as they both hostedThe 2009 World Rafting Championship.[230][231]The reason the Tara river is immensely popular for whitewater rafting is because it contains the deepestriver canyonin Europe, theTara River Canyon.[232][233]

Most recently, theHuffington Postnamed Bosnia and Herzegovina the "9th Greatest Adventure in the World for 2013", adding that the country boasts "the cleanest water and air in Europe; the greatest untouched forests; and the most wildlife. The best way to experience is the three rivers trip, which purls through the best the Balkans have to offer."[234]

Infrastructure

Transport

Sarajevo International Airport,also known as Butmir Airport, is the maininternational airportin Bosnia and Herzegovina, located 3.3NM(6.1 km; 3.8 mi) southwest of theSarajevo main railway station[235]in the city ofSarajevoin the suburb ofButmir.

Railway operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina are successors of theYugoslav Railwayswithin the country boundaries following independence from theformer Yugoslaviain 1992. Today, they are operated by theRailways of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina(ŽFBiH) in theFederation of Bosnia and Herzegovinaand byRepublika Srpska Railways(ŽRS) inRepublika Srpska.

Telecommunications

The Bosnian communications market was fullyliberalisedin January 2006. The threelandlinetelephone operators predominantly provide services in their operating areas but have nationwide licenses for domestic and international calls. Mobile data services are also available, including high-speedEDGE,3Gand4Gservices.[236]

Oslobođenje(Liberation), founded in 1943, is one of the country's longest running continuously circulating newspapers. There are many national publications, including theDnevni avaz(Daily Voice), founded in 1995, andJutarnje Novine(Morning News), to name but a few in circulation in Sarajevo.[237]Other local periodicals include the CroatianHrvatska riječnewspaper and BosnianStartmagazine, as well asSlobodna Bosna(Free Bosnia) andBH Dani(BH Days) weekly newspapers.Novi Plamen,a monthly magazine, was the most left-wing publication. International news stationAl Jazeeramaintains asister channelcatering to theBalkanregion,Al Jazeera Balkans,broadcasting out of and based in Sarajevo.[238]Since 2014, theN1 platformhas broadcast as an affiliate ofCNN International,with offices in Sarajevo,ZagrebandBelgrade.[239]

As of 2021, Bosnia and Herzegovina ranked second highest inpress freedomin the region, afterCroatia,and is placed 58th internationally.[240]

As of December 2021[update],there are 3,374,094 internet users in the country, or 95.55% of the entire population.[241]

Education

Higher educationhas a long and rich tradition in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The first bespoke higher-education institution was a school ofSufiphilosophy established byGazi Husrev-begin 1531. Numerous other religious schools then followed. In 1887, under theAustro-Hungarian Empire,aSharialaw school began a five-year program.[242]In the 1940s, theUniversity of Sarajevobecame the city's first secular higher education institute. In the 1950s, post-bachelaurate graduate degrees became available.[243]Severely damaged during thewar,it was recently rebuilt in partnership with more than 40 other universities. There are various other institutions of higher education, including:University Džemal Bijedić of Mostar,University of Banja Luka,University of Mostar,University of East Sarajevo,University of Tuzla,American University in Bosnia and Herzegovinaand theAcademy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina,which is held in high regard as one of the most prestigious creative arts academies in the region.

Also, Bosnia and Herzegovina is home to several private and international higher education institutions, some of which are:

- Sarajevo School of Science and Technology

- International University of Sarajevo

- American University in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Sarajevo Graduate School of Business

- International Burch University

- United World College in Mostar

Primary schooling lasts for nine years. Secondary education is provided by general and technical secondary schools (typicallyGymnasiums) where studies typically last for four years. All forms of secondary schooling include an element ofvocational training.Pupils graduating from general secondary schools obtain theMaturaand can enroll in any tertiary educational institution or academy by passing a qualification examination prescribed by the governing body or institution. Students graduating technical subjects obtain aDiploma.[244]

Culture

Architecture

Thearchitecture of Bosnia and Herzegovinais largely influenced by four major periods where political and social changes influenced the creation of distinct cultural and architectural habits of the population. Each period made its influence felt and contributed to a greater diversity of cultures and architectural language in this region.

Media

Some television, magazines, and newspapers in Bosnia and Herzegovina are state-owned, and some are for-profit corporations funded byadvertising,subscription,and other sales-related revenues. TheConstitution of Bosnia and Herzegovinaguaranteesfreedom of speech.

As acountry in transitionwith a post-war legacy and acomplex domestic political structure,Bosnia and Herzegovina's media system is under transformation. In the early post-war period (1995–2005), media development was guided mainly by international donors and cooperation agencies, who invested to help reconstruct, diversify, democratize and professionalize media outlets.[245][246]

Post-war developments included the establishment of an independent Communication Regulatory Agency, the adoption of a Press Code, the establishment of the Press Council, the decriminalization of libel and defamation, the introduction of a rather advanced Freedom of Access to Information Law, and the creation of a Public Service Broadcasting System from the formerly state-owned broadcaster. Yet, internationally backed positive developments have been often obstructed by domestic elites, and the professionalisation of media and journalists has proceeded only slowly. High levels of partisanship and linkages between the media and the political systems hinder the adherence to professional code of conducts.[246]

Literature

Bosnia and Herzegovina has a rich literature, including theNobel PrizewinnerIvo Andrićand poets such asAntun Branko Šimić,Aleksa Šantić,Jovan DučićandMak Dizdar,writers such asZlatko Topčić,Meša Selimović,Semezdin Mehmedinović,Miljenko Jergović,Isak Samokovlija,Safvet-beg Bašagić,Abdulah Sidran,Petar Kočić,Aleksandar HemonandNedžad Ibrišimović.

TheNational Theaterwas founded in 1919 inSarajevoand its first director was dramatistBranislav Nušić.Magazines such asNovi PlamenorSarajevske sveskeare some of the more prominent publications covering cultural and literary themes.

By the late 1950s, Ivo Andrić's works had been translated into a number of languages. In 1958, theAssociation of Writers of Yugoslavianominated Andrić as its first ever candidate for theNobel Prize in Literature

Art

Theart of Bosnia and Herzegovinawas always evolving and ranged from the original medieval tombstones calledStećcito paintings inKotromanićcourt. However, only with the arrival ofAustro-Hungariansdid the painting renaissance in Bosnia really begin to flourish. The first educated artists from European academies appeared with the beginning of the 20th century. Among those are:Gabrijel Jurkić,Petar Šain,Roman PetrovićandLazar Drljača.

AfterWorld War II,artists likeMersad BerberandSafet Zecrose in popularity.

In 2007,Ars Aevi,a museum of contemporary art that includes works by renowned world artists, was founded in Sarajevo.

Music

Typical Bosnian songs areganga,rera,and the traditional Slavic music for the folk dances such askolo,while from the Ottoman era the most popular isSevdalinka.Pop and Rock music has a tradition here as well, with the more famous musicians includingDino Zonić,Goran Bregović,Davorin Popović,Kemal Monteno,Zdravko Čolić,Elvir Laković Laka,Edo Maajka,Hari Varešanović,Dino Merlin,Mladen Vojičić Tifa,Željko Bebek,etc. Other composers such asĐorđe Novković,Al' Dino,Haris Džinović,Kornelije Kovač,and manyrock and pop bands,for example,Bijelo Dugme,Crvena jabuka,Divlje jagode,Indexi,Plavi orkestar,Zabranjeno Pušenje,Ambasadori,Dubioza kolektiv,who were among the leading ones in the former Yugoslavia. Bosnia is home to the composerDušan Šestić,the creator of theNational Anthem of Bosnia and Herzegovinaand father of singerMarija Šestić,to the jazz musician, educator and Bosnian jazz ambassadorSinan Alimanović,composerSaša Lošićand pianistSaša Toperić.In the villages, especially inHerzegovina,Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats play the ancientgusle.The gusle is used mainly to recite epic poems in a usually dramatic tone.

Probably the most distinctive and identifiably "Bosnian" of music, Sevdalinka is a kind of emotional, melancholic folk song that often describes sad subjects such as love and loss, the death of a dear person or heartbreak. Sevdalinkas were traditionally performed with asaz,a Turkish string instrument, which was later replaced by the accordion. However the more modern arrangement is typically a vocalist accompanied by the accordion along with snare drums, upright bass, guitars, clarinets and violins.