Botulinum toxin

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Botox, Myobloc, Jeuveau, others |

| Other names | BoNT, botox |

| Biosimilars | abobotulinumtoxinA, daxibotulinumtoxinA, daxibotulinumtoxinA-lanm, evabotulinumtoxinA, incobotulinumtoxinA, letibotulinumtoxinA, letibotulinumtoxinA-wlbg,[1]onabotulinumtoxinA, prabotulinumtoxinA, relabotulinumtoxinA, rimabotulinumtoxinB |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | |

| MedlinePlus | a619021 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular,subcutaneous,intradermal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

|

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.088.372 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6760H10447N1743O2010S32 |

| Molar mass | 149323.05g·mol−1 |

Botulinum toxin,orbotulinum neurotoxin(commonly calledbotox), is a highly potentneurotoxicproteinproduced by thebacteriumClostridium botulinumand related species.[24]It prevents the release of theneurotransmitteracetylcholinefromaxonendings at theneuromuscular junction,thus causingflaccid paralysis.[25]The toxin causes the diseasebotulism.[26]The toxin is also used commercially for medical and cosmetic purposes.[27][28]Botulinum toxin is an acetylcholine release inhibitor and a neuromuscular blocking agent.[1][23]

The seven main types of botulinum toxin are named types A to G (A, B, C1, C2, D, E, F and G).[27][29]New types are occasionally found.[30][31]Types A and B are capable of causing disease in humans, and are also used commercially and medically.[32][33][34]Types C–G are less common; types E and F can cause disease in humans, while the other types cause disease in other animals.[35]

Botulinum toxins are among the most potent toxins known to science.[36][37]Intoxication can occur naturally as a result of either wound or intestinal infection or by ingesting formed toxin in food. The estimated humanmedian lethal doseof type A toxin is 1.3–2.1ng/kgintravenouslyorintramuscularly,10–13ng/kg when inhaled, or 1000ng/kg when taken by mouth.[38]

Medical uses

[edit]Botulinum toxin is used to treat a number of therapeutic indications, many of which are not part of the approved drug label.[28]

Muscle spasticity

[edit]Botulinum toxin is used to treat a number of disorders characterized by overactive muscle movement, includingcerebral palsy,[32][33]post-strokespasticity,[39]post-spinal cord injury spasticity,[40]spasmsof the head and neck,[41]eyelid,[26]vagina,[42]limbs, jaw, andvocal cords.[43]Similarly, botulinum toxin is used to relax the clenching of muscles, including those of theesophagus,[44]jaw,[45]lower urinary tractandbladder,[46]or clenching of the anus which can exacerbateanal fissure.[47]Botulinum toxin appears to be effective forrefractoryoveractive bladder.[48]

Other muscle disorders

[edit]Strabismus,otherwise known as improper eye alignment, is caused by imbalances in the actions of muscles that rotate the eyes. This condition can sometimes be relieved by weakening a muscle that pulls too strongly, or pulls against one that has been weakened by disease or trauma. Muscles weakened by toxin injection recover from paralysis after several months, so injection might seem to need to be repeated, but muscles adapt to the lengths at which they are chronically held,[49]so that if a paralyzed muscle is stretched by its antagonist, it grows longer, while the antagonist shortens, yielding a permanent effect.[50]

In January 2014, botulinum toxin was approved by UK'sMedicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agencyfor treatment of restricted ankle motion due to lower-limb spasticity associated with stroke in adults.[51][52]

In July 2016, the USFood and Drug Administration(FDA) approved abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport) for injection for the treatment of lower-limb spasticity in pediatric patients two years of age and older.[53][54]AbobotulinumtoxinA is the first and only FDA-approved botulinum toxin for the treatment of pediatric lower limb spasticity.[55]In the US, theFDA approvesthe text of the labels of prescription medicines and for which medical conditions the drug manufacturer may sell the drug. However, prescribers may freely prescribe them for any condition they wish, also known asoff-label use.[56]Botulinum toxins have been used off-label for several pediatric conditions, includinginfantile esotropia.[57]

Excessive sweating

[edit]AbobotulinumtoxinA has been approved for the treatment of axillaryhyperhidrosis,which cannot be managed by topical agents.[43][58]

Migraine

[edit]In 2010, the FDA approvedintramuscularbotulinum toxin injections forprophylactictreatmentofchronicmigraineheadache.[59]However, the use of botulinum toxin injections for episodic migraine has not been approved by the FDA.[60]

Cosmetic uses

[edit]

In cosmetic applications, botulinum toxin is considered relatively safe and effective[61]for reduction of facialwrinkles,especially in the uppermost third of the face.[62]Commercial forms are marketed under the brand names Botox Cosmetic/Vistabel fromAllergan,Dysport/Azzalure fromGaldermaandIpsen,Xeomin/Bocouture from Merz, Jeuveau/Nuceiva from Evolus, manufactured byDaewoongin South Korea.[63]The effects of botulinum toxin injections forglabellarlines ('11's lines' between the eyes) typically last two to four months and in some cases, product-dependent, with some patients experiencing a longer duration of effect of up to six months or longer.[62]Injection of botulinum toxin into the muscles under facial wrinkles causes relaxation of those muscles, resulting in the smoothing of the overlying skin.[62]Smoothing of wrinkles is usually visible three to five days after injection, with maximum effect typically a week following injection.[62]Muscles can be treated repeatedly to maintain the smoothed appearance.[62]

DaxibotulinumtoxinA (Daxxify) was approved for medical use in the United States in September 2022.[23][64]It is indicated for the temporary improvement in the appearance of moderate to severe glabellar lines (wrinkles between the eyebrows).[23][64][65]DaxibotulinumtoxinA is an acetylcholine release inhibitor and neuromuscular blocking agent.[23]The FDA approved daxibotulinumtoxinA based on evidence from two clinical trials (Studies GL-1 and GL-2), of 609 adults with moderate to severe glabellar lines.[64]The trials were conducted at 30 sites in the United States and Canada.[64]Both trials enrolled participants 18 to 75 years old with moderate to severe glabellar lines.[64]Participants received a single intramuscular injection of daxibotulinumtoxinA or placebo at five sites within the muscles between the eyebrows.[64]The most common side effects of daxibotulinumtoxinA are headache, drooping eyelids, and weakness of facial muscles.[64]

LetibotulinumtoxinA (Letybo) was approved for medical use in the United States in February 2024.[1][66]It is indicated to temporarily improve the appearance of moderate-to-severe glabellar lines.[1][67]The FDA approved letibotulinumtoxinA based on evidence from three clinical trials (BLESS I [NCT02677298], BLESS II [NCT02677805], and BLESS III [NCT03985982]) of 1,271 participants with moderate to severe wrinkles between the eyebrows for efficacy and safety assessment.[66]These trials were conducted at 31 sites in the United States and the European Union.[66]All three trials enrolled participants 18 to 75 years old with moderate to severe glabellar lines (wrinkles between the eyebrows).[66]Participants received a single intramuscular injection of letibotulinumtoxinA or placebo at five sites within the muscles between the eyebrows.[66]The most common side effects of letibotulinumtoxinA are headache, drooping of eyelid and brow, and twitching of eyelid.[66]

Other

[edit]Botulinum toxin is also used to treat disorders of hyperactive nerves including excessive sweating,[58]neuropathic pain,[68]and someallergysymptoms.[43]In addition to these uses, botulinum toxin is being evaluated for use in treatingchronic pain.[69]Studies show that botulinum toxin may be injected into arthritic shoulder joints to reduce chronic pain and improve range of motion.[70]The use of botulinum toxin A in children withcerebral palsyis safe in the upper and lower limb muscles.[32][33]

Side effects

[edit]While botulinum toxin is generally considered safe in a clinical setting, serious side effects from its use can occur. Most commonly, botulinum toxin can be injected into the wrong muscle group or with time spread from the injection site, causing temporary paralysis of unintended muscles.[71]

Side effects from cosmetic use generally result from unintended paralysis of facial muscles. These include partial facial paralysis, muscle weakness, andtrouble swallowing.Side effects are not limited to direct paralysis, however, and can also include headaches, flu-like symptoms, and allergic reactions.[72]Just as cosmetic treatments only last a number of months, paralysis side effects can have the same durations.[73]At least in some cases, these effects are reported to dissipate in the weeks after treatment.[74]Bruising at the site of injection is not a side effect of the toxin, but rather of the mode of administration, and is reported as preventable if the clinician applies pressure to the injection site; when it occurs, it is reported in specific cases to last 7–11 days.[75]When injecting the masseter muscle of the jaw, loss of muscle function can result in a loss or reduction of power to chew solid foods.[72]With continued high doses, the muscles can atrophy or lose strength; research has shown that those muscles rebuild after a break from Botox.[76]

Side effects from therapeutic use can be much more varied depending on the location of injection and the dose of toxin injected. In general, side effects from therapeutic use can be more serious than those that arise during cosmetic use. These can arise from paralysis of critical muscle groups and can includearrhythmia,heart attack,and in some cases, seizures, respiratory arrest, and death.[72]Additionally, side effects common in cosmetic use are also common in therapeutic use, including trouble swallowing, muscle weakness, allergic reactions, and flu-like syndromes.[72]

In response to the occurrence of these side effects, in 2008, the FDA notified the public of the potential dangers of the botulinum toxin as a therapeutic. Namely, the toxin can spread to areas distant from the site of injection and paralyze unintended muscle groups, especially when used for treating muscle spasticity in children treated for cerebral palsy.[77]In 2009, the FDA announced that boxed warnings would be added to available botulinum toxin products, warning of their ability to spread from the injection site.[78][79][80][81]However, the clinical use of botulinum toxin A in cerebral palsy children has been proven to be safe with minimal side effects.[32][33]Additionally, the FDA announced name changes to several botulinum toxin products, to emphasize that the products are not interchangeable and require different doses for proper use. Botox and Botox Cosmetic were given the generic name of onabotulinumtoxinA, Myobloc as rimabotulinumtoxinB, and Dysport retained its generic name of abobotulinumtoxinA.[82][78]In conjunction with this, the FDA issued a communication to health care professionals reiterating the new drug names and the approved uses for each.[83]A similar warning was issued byHealth Canadain 2009, warning that botulinum toxin products can spread to other parts of the body.[84]

Role in disease

[edit]Botulinum toxin produced byClostridium botulinum(an anaerobic, gram-positive bacterium) is the cause of botulism.[26]Humans most commonly ingest the toxin from eating improperly canned foods in whichC. botulinumhas grown. However, the toxin can also be introduced through an infected wound. In infants, the bacteria can sometimes grow in the intestines and produce botulinum toxin within the intestine and can cause a condition known asfloppy baby syndrome.[85]In all cases, the toxin can then spread, blocking nerves and muscle function. In severe cases, the toxin can block nerves controlling the respiratory system or heart, resulting in death.[24]

Botulism can be difficult to diagnose, as it may appear similar to diseases such asGuillain–Barré syndrome,myasthenia gravis,andstroke.Other tests, such as brain scan and spinal fluid examination, may help to rule out other causes. If the symptoms of botulism are diagnosed early, various treatments can be administered. In an effort to remove contaminated food that remains in the gut, enemas or induced vomiting may be used.[86]For wound infections, infected material may be removed surgically.[86]Botulinum antitoxin is available and may be used to prevent the worsening of symptoms, though it will not reverse existing nerve damage. In severe cases, mechanical respiration may be used to support people with respiratory failure.[86]The nerve damage heals over time, generally over weeks to months.[87]With proper treatment, the case fatality rate for botulinum poisoning can be greatly reduced.[86]

Two preparations of botulinum antitoxins are available for treatment of botulism. Trivalent (serotypes A, B, E) botulinumantitoxinis derived from equine sources using wholeantibodies.The second antitoxin isheptavalent botulinum antitoxin(serotypes A, B, C, D, E, F, G), which is derived from equine antibodies that have been altered to make them less immunogenic. This antitoxin is effective against all main strains of botulism.[88][31]

Mechanism of action

[edit]

Botulinum toxin exerts its effect by cleaving key proteins required for nerve activation. First, the toxin binds specifically to presynaptic surface ofneuronsthat use the neurotransmitteracetylcholine.Once bound to the nerve terminal, the neurontakes upthe toxin into avesicleby receptor-mediatedendocytosis.[90]As the vesicle moves farther into the cell, it acidifies, activating a portion of the toxin that triggers it to push across the vesicle membrane and into the cellcytoplasm.[24]Botulinum neurotoxins recognize distinct classes of receptors simultaneously (gangliosides,synaptotagminandSV2).[91]Once inside the cytoplasm, the toxin cleavesSNARE proteins(proteins that mediate vesicle fusion, with their target membrane bound compartments) meaning that the acetylcholine vesicles cannot bind to the intracellular cell membrane,[90]preventing the cell from releasing vesicles of neurotransmitter. This stops nerve signaling, leading toflaccid paralysis.[24][91]

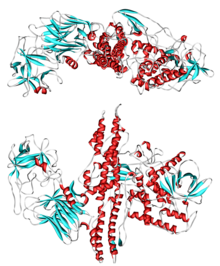

The toxin itself is released from the bacterium as a single chain, then becomes activated when cleaved by its own proteases.[43]The active form consists of a two-chainproteincomposed of a 100-kDaheavy chainpolypeptidejoined viadisulfide bondto a 50-kDa light chain polypeptide.[92]The heavy chain contains domains with several functions; it has the domain responsible for binding specifically topresynapticnerve terminals, as well as the domain responsible for mediating translocation of the light chain into the cell cytoplasm as the vacuole acidifies.[24][92]The light chain is a M27-family zincmetalloproteaseand is the active part of the toxin. It is translocated into the host cell cytoplasm where it cleaves the host proteinSNAP-25,a member of the SNARE protein family, which is responsible forfusion.The cleaved SNAP-25 cannot mediate fusion of vesicles with the host cell membrane, thus preventing the release of theneurotransmitteracetylcholine from axon endings.[24]This blockage is slowly reversed as the toxin loses activity and the SNARE proteins are slowly regenerated by the affected cell.[24]

The seven toxin serotypes (A–G) are traditionally separated by their antigenicity. They have different tertiary structures and sequence differences.[92][93]While the different toxin types all target members of the SNARE family, different toxin types target different SNARE family members.[89]The A, B, and E serotypes cause human botulism, with the activities of types A and B enduring longestin vivo(from several weeks to months).[92]Existing toxin types can recombine to create "hybrid" (mosaic, chimeric) types. Examples include BoNT/CD, BoNT/DC, and BoNT/FA, with the first letter indicating the light chain type and the latter indicating the heavy chain type.[94]BoNT/FA received considerable attention under the name "BoNT/H", as it was mistakenly thought it could not be neutralized by any existing antitoxin.[31]

Botulinum toxins areAB toxinsand closely related toAnthrax toxin,Diphtheria toxin,and in particulartetanus toxin.The two are collectively known asClostridiumneurotoxinsand the light chain is classified byMEROPSasfamily M27.Nonclassical types include BoNT/X (P0DPK1), which is toxic in mice and possibly in humans;[30]a BoNT/J (A0A242DI27) found in cowEnterococcus;[95]and a BoNT/Wo (A0A069CUU9) found in the rice-colonizingWeissella oryzae.[94]

History

[edit]Initial descriptions and discovery ofClostridium botulinum

[edit]One of the earliest recorded outbreaks of foodborne botulism occurred in 1793 in the village ofWildbadin what is nowBaden-Württemberg,Germany. Thirteen people became sick and six died after eating pork stomach filled withblood sausage,a local delicacy. Additional cases of fatal food poisoning inWürttembergled the authorities to issue a public warning against consuming smoked blood sausages in 1802 and to collect case reports of "sausage poisoning".[96]Between 1817 and 1822, the German physicianJustinus Kernerpublished the first complete description of the symptoms of botulism, based on extensive clinical observations and animal experiments. He concluded that the toxin develops in bad sausages under anaerobic conditions, is a biological substance, acts on the nervous system, and is lethal even in small amounts.[96]Kerner hypothesized that this "sausage toxin" could be used to treat a variety of diseases caused by an overactive nervous system, making him the first to suggest that it could be used therapeutically.[97]In 1870, the German physician Müller coined the termbotulismto describe the disease caused by sausage poisoning, from the Latin wordbotulus,meaning 'sausage'.[97]

In 1895Émile van Ermengem,a Belgian microbiologist, discovered what is now calledClostridium botulinumand confirmed that a toxin produced by the bacteria causes botulism.[98]On 14 December 1895, there was a large outbreak of botulism in the Belgian village ofEllezellesthat occurred at a funeral where people ate pickled and smoked ham; three of them died. By examining the contaminated ham and performing autopsies on the people who died after eating it, van Ermengem isolated an anaerobic microorganism that he calledBacillus botulinus.[96]He also performed experiments on animals with ham extracts, isolated bacterial cultures, and toxins extracts from the bacteria. From these he concluded that the bacteria themselves do not cause foodborne botulism, but rather produce a toxin that causes the disease after it is ingested.[99]As a result of Kerner's and van Ermengem's research, it was thought that only contaminated meat or fish could cause botulism. This idea was refuted in 1904 when a botulism outbreak occurred inDarmstadt,Germany, because of canned white beans. In 1910, the German microbiologist J. Leuchs published a paper showing that the outbreaks in Ellezelles and Darmstadt were caused by different strains ofBacillus botulinusand that the toxins were serologically distinct.[96]In 1917,Bacillus botulinuswas renamedClostridium botulinum,as it was decided that termBacillusshould only refer to a group of aerobic microorganisms, whileClostridiumwould be only used to describe a group of anaerobic microorganisms.[98]In 1919,Georgina Burkeused toxin-antitoxin reactions to identify two strains ofClostridium botulinum,which she designated A and B.[98]

Food canning

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(August 2018) |

Over the next three decades, 1895–1925, as food canning was approaching a billion-dollar-a-year industry, botulism was becoming a public health hazard.Karl Friedrich Meyer,a Swiss-American veterinary scientist, created a center at the Hooper Foundation in San Francisco, where he developed techniques for growing the organism and extracting the toxin, and conversely, for preventing organism growth and toxin production, and inactivating the toxin by heating. The California canning industry was thereby preserved.[100]

World War II

[edit]With the outbreak of World War II, weaponization of botulinum toxin was investigated atFort Detrickin Maryland. Carl Lamanna and James Duff[101]developed the concentration and crystallization techniques that Edward J. Schantz used to create the first clinical product. When the Army'sChemical Corpswas disbanded, Schantz moved to the Food Research Institute in Wisconsin, where he manufactured toxin for experimental use and provided it to the academic community.

The mechanism of botulinum toxin action – blocking the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine from nerve endings – was elucidated in the mid-20th century,[102]and remains an important research topic. Nearly all toxin treatments are based on this effect in various body tissues.

Strabismus

[edit]Ophthalmologists specializing in eye muscle disorders (strabismus) had developed the method of EMG-guided injection (using theelectromyogram,the electrical signal from an activated muscle, to guide injection) of local anesthetics as a diagnostic technique for evaluating an individual muscle's contribution to an eye movement.[103]Becausestrabismus surgeryfrequently needed repeating, a search was undertaken for non-surgical, injection treatments using various anesthetics, alcohols, enzymes, enzyme blockers, and snake neurotoxins. Finally, inspired byDaniel B. Drachman's work with chicks at Johns Hopkins,[104]Alan B. Scottand colleagues injected botulinum toxin into monkey extraocular muscles.[105]The result was remarkable; a few picograms induced paralysis that was confined to the target muscle, long in duration, and without side effects.

After working out techniques for freeze-drying, buffering withalbumin,and assuring sterility, potency, and safety, Scott applied to the FDA for investigational drug use, and began manufacturing botulinum type A neurotoxin in his San Francisco lab. He injected the first strabismus patients in 1977, reported its clinical utility in 1980,[106]and had soon trained hundreds of ophthalmologists in EMG-guided injection of the drug he named Oculinum ( "eye aligner" ).

In 1986, Oculinum Inc, Scott's micromanufacturer and distributor of botulinum toxin, was unable to obtain product liability insurance, and could no longer supply the drug. As supplies became exhausted, people who had come to rely on periodic injections became desperate. For four months, as liability issues were resolved, American blepharospasm patients traveled to Canadian eye centers for their injections.[107]

Based on data from thousands of people collected by 240 investigators, Oculinum Inc (which was soon acquired by Allergan) received FDA approval in 1989 to market Oculinum for clinical use in the United States to treat adult strabismus andblepharospasm.Allergan then began using the trademark Botox.[108]This original approval was granted under the1983 US Orphan Drug Act.[109]

Cosmetics

[edit]

The effect of botulinum toxin type-A on reducing and eliminating forehead wrinkles was first described and published by Richard Clark, MD, a plastic surgeon from Sacramento, California. In 1987 Clark was challenged with eliminating the disfigurement caused by only the right side of the forehead muscles functioning after the left side of the forehead was paralyzed during a facelift procedure. This patient had desired to look better from her facelift, but was experiencing bizarre unilateral right forehead eyebrow elevation while the left eyebrow drooped, and she constantly demonstrated deep expressive right forehead wrinkles while the left side was perfectly smooth due to the paralysis. Clark was aware that Botulinum toxin was safely being used to treat babies with strabismus and he requested and was granted FDA approval to experiment with Botulinum toxin to paralyze the moving and wrinkling normal functioning right forehead muscles to make both sides of the forehead appear the same. This study and case report of the cosmetic use of Botulinum toxin to treat a cosmetic complication of a cosmetic surgery was the first report on the specific treatment of wrinkles and was published in the journalPlastic and Reconstructive Surgeryin 1989.[110]Editors of the journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons have clearly stated "the first described use of the toxin in aesthetic circumstances was by Clark and Berris in 1989."[111]

Also in 1987, Jean and Alastair Carruthers, both doctors inVancouver, British Columbia,observed that blepharospasm patients who received injections around the eyes and upper face also enjoyed diminished facial glabellar lines ( "frown lines" between the eyebrows). Alastair Carruthers reported that others at the time also noticed these effects and discussed the cosmetic potential of botulinum toxin.[112]Unlike other investigators, the Carruthers did more than just talk about the possibility of using botulinum toxin cosmetically. They conducted a clinical study on otherwise normal individuals whose only concern was their eyebrow furrow. They performed their study between 1987 and 1989 and presented their results at the 1990 annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Their findings were subsequently published in 1992.[113]

Chronic pain

[edit]William J. Binderreported in 2000 that people who had cosmetic injections around the face reported relief from chronic headache.[114]This was initially thought to be an indirect effect of reduced muscle tension, but the toxin is now known to inhibit release of peripheral nociceptive neurotransmitters, suppressing the central pain processing systems responsible formigraineheadache.[115][116]

Society and culture

[edit]Economics

[edit]This article needs to beupdated.(October 2017) |

As of 2018[update],botulinum toxin injections are the most common cosmetic operation, with 7.4 million procedures in the United States, according to theAmerican Society of Plastic Surgeons.[117]

The global market for botulinum toxin products, driven by their cosmetic applications, was forecast to reach $2.9 billion by 2018. The facial aesthetics market, of which they are a component, was forecast to reach $4.7 billion ($2 billion in the US) in the same timeframe.[118]

US market

[edit]In 2020, 4,401,536 botulinum toxin Type A procedures were administered.[119]In 2019 the botulinum toxin market made US$3.19 billion.[120]

Botox cost

[edit]Botox cost is generally determined by the number of units administered (avg. $10–30 per unit) or by the area ($200–1000) and depends on expertise of a physician, clinic location, number of units, and treatment complexity.[121]

Insurance

[edit]In the US, botox for medical purposes is usually covered by insurance if deemed medically necessary by a doctor and covers a plethora of medical problems including overactive bladder (OAB), urinary incontinence due to neurologic conditions, headaches and migraines, TMJ, spasticity in adults, cervical dystonia in adults, severe axillary hyperhidrosis (or other areas of the body), blepharospasm, upper or lower limb spasticity.[122][123]

Hyperhidrosis

[edit]Botox for excessive sweating is FDA approved.[71]

Cosmetic

[edit]Standard areas for aesthetics botox injections include facial and other areas that can form fine lines and wrinkles due to every day muscle contractions and/or facial expressions such as smiling, frowning, squinting, and raising eyebrows. These areas include the glabellar region between the eyebrows, horizontal lines on the forehead, crow's feet around the eyes, and even circular bands that form around the neck secondary to platysmal hyperactivity.[124]

Bioterrorism

[edit]Botulinum toxin has been recognized as a potential agent for use inbioterrorism.[125]It can be absorbed through the eyes, mucous membranes, respiratory tract, and non-intact skin.[126] The effects of botulinum toxin are different from those of nerve agents involved insofar in that botulism symptoms develop relatively slowly (over several days), while nerve agent effects are generally much more rapid. Evidence suggests that nerve exposure (simulated by injection ofatropineandpralidoxime) will increase mortality by enhancing botulinum toxin's mechanism of toxicity.[127] With regard to detection, protocols usingNBCdetection equipment (such as M-8 paper or the ICAM) will not indicate a "positive" when samples containing botulinum toxin are tested.[128]To confirm a diagnosis of botulinum toxin poisoning, therapeutically or to provide evidence in death investigations, botulinum toxin may be quantitated by immunoassay of human biological fluids; serum levels of 12–24 mouse LD50units per milliliter have been detected in poisoned people.[129]

During the early 1980s, German and French newspapers reported that the police had raided aBaader-Meinhofgang safe house in Paris and had found a makeshift laboratory that contained flasks full ofClostridium botulinum,which makes botulinum toxin. Their reports were later found to be incorrect; no such lab was ever found.[130]

Brand names

[edit]The examples and perspective in this articledeal primarily with the United States and do not represent aworldwide viewof the subject.(April 2017) |

Commercial forms are marketed under the brand names Botox (onabotulinumtoxinA),[19][82][131]Dysport/Azzalure (abobotulinumtoxinA),[82][132]Letybo (letibotulinumtoxinA),[1][2][133]Myobloc (rimabotulinumtoxinB),[21][82]Xeomin/Bocouture (incobotulinumtoxinA),[134]and Jeuveau (prabotulinumtoxinA).[135][63]

Botulinum toxin A is sold under the brand names Jeuveau, Botox, and Xeomin. Botulinum toxin B is sold under the brand name Myobloc.[21]

In the United States, botulinum toxin products are manufactured by a variety of companies, for both therapeutic and cosmetic use. A US supplier reported in its company materials in 2011 that it could "supply the world's requirements for 25indicationsapproved by Government agencies around the world "with less than one gram of raw botulinum toxin.[136]Myobloc or Neurobloc, a botulinum toxin type B product, is produced by Solstice Neurosciences, a subsidiary of US WorldMeds. AbobotulinumtoxinA), a therapeutic formulation of the type A toxin manufactured byGaldermain the United Kingdom, is licensed for the treatment of focal dystonias and certain cosmetic uses in the US and other countries.[83]LetibotulinumtoxinA (Letybo) was approved for medical use in the United States in February 2024.[1]

Besides the three primary US manufacturers, numerous other botulinum toxin producers are known. Xeomin, manufactured in Germany byMerz,is also available for both therapeutic and cosmetic use in the US.[137]Lanzhou Institute of Biological Products in China manufactures a botulinum toxin type-A product; as of 2014, it was the only botulinum toxin type-A approved in China.[137]Botulinum toxin type-A is also sold as Lantox and Prosigne on the global market.[138]Neuronox, a botulinum toxin type-A product, was introduced by Medy-Tox of South Korea in 2009.[139]

Toxin production

[edit]Botulism toxins are produced by bacteria of the genusClostridium,namelyC. botulinum,C. butyricum,C. baratiiandC. argentinense,[140]which are widely distributed, including in soil and dust. Also, the bacteria can be found inside homes on floors, carpet, and countertops even after cleaning.[141]Complicating the problem is that the taxonomy forC. botulinumremains chaotic. The toxin has likely beenhorizontally transferredacross lineages, contributing to the multi-species pattern seen today.[142][143]

Food-borne botulism results, indirectly, from ingestion of food contaminated withClostridiumspores, where exposure to ananaerobic environmentallows the spores to germinate, after which the bacteria can multiply and produce toxin.[141]Critically, ingestion of toxin rather than spores or vegetative bacteria causesbotulism.[141]Botulism is nevertheless known to be transmitted through canned foods not cooked correctly before canning or after can opening, so is preventable.[141]Infant botulism arising from consumption of honey or any other food that can carry these spores can be prevented by eliminating these foods from diets of children less than 12 months old.[144]

Organism and toxin susceptibilities

[edit]This sectionneeds expansionwith: modern content and referencing on antibiotic susceptibilities. You can help byadding to it.(February 2015) |

Proper refrigeration at temperatures below 4.4 °C (39.9 °F) slows the growth ofC. botulinum.[145]The organism is also susceptible to high salt, high oxygen, and low pH levels.[35][failed verification]The toxin itself is rapidly destroyed by heat, such as in thorough cooking.[146]The spores that produce the toxin are heat-tolerant and will survive boiling water for an extended period of time.[147]

The botulinum toxin isdenaturedand thus deactivated at temperatures greater than 85 °C (185 °F) for five minutes.[35]As a zincmetalloprotease(see below), the toxin's activity is also susceptible, post-exposure, toinhibitionbyprotease inhibitors,e.g., zinc-coordinatinghydroxamates.[92][148]

Research

[edit]Blepharospasm and strabismus

[edit]University-based ophthalmologists in the US and Canada further refined the use of botulinum toxin as a therapeutic agent. By 1985, a scientific protocol of injection sites and dosage had been empirically determined for treatment ofblepharospasmand strabismus.[149]Side effects in treatment of this condition were deemed to be rare, mild and treatable.[150]The beneficial effects of the injection lasted only four to six months. Thus, blepharospasm patients required re-injection two or three times a year.[151]

In 1986, Scott's micromanufacturer and distributor of Botox was no longer able to supply the drug because of an inability to obtain product liability insurance. People became desperate, as supplies of Botox were gradually consumed, forcing him to abandon people who would have been due for their next injection. For a period of four months, American blepharospasm patients had to arrange to have their injections performed by participating doctors at Canadian eye centers until the liability issues could be resolved.[107]

In December 1989, Botox was approved by the US FDA for the treatment of strabismus, blepharospasm, andhemifacial spasmin people over 12 years old.[108]

In the case of treatment ofinfantile esotropiain people younger than 12 years of age, several studies have yielded differing results.[57][152]

Cosmetic

[edit]The effect of botulinum toxin type-A on reducing and eliminating forehead wrinkles was first described and published by Richard Clark, MD, a plastic surgeon from Sacramento, California. In 1987 Clark was challenged with eliminating the disfigurement caused by only the right side of the forehead muscles functioning after the left side of the forehead was paralyzed during a facelift procedure. This patient had desired to look better from her facelift, but was experiencing bizarre unilateral right forehead eyebrow elevation while the left eyebrow drooped and she emoted with deep expressive right forehead wrinkles while the left side was perfectly smooth due to the paralysis. Clark was aware that botulinum toxin was safely being used to treat babies with strabismus and he requested and was granted FDA approval to experiment with botulinum toxin to paralyze the moving and wrinkling normal functioning right forehead muscles to make both sides of the forehead appear the same. This study and case report on the cosmetic use of botulinum toxin to treat a cosmetic complication of a cosmetic surgery was the first report on the specific treatment of wrinkles and was published in the journalPlastic and Reconstructive Surgeryin 1989.[110]Editors of the journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons have clearly stated "the first described use of the toxin in aesthetic circumstances was by Clark and Berris in 1989."[111]

J. D. and J. A. Carruthers also studied and reported in 1992 the use of botulinum toxin type-A as a cosmetic treatment.[78] They conducted a study of participants whose only concern was their glabellar forehead wrinkle or furrow. Study participants were otherwise normal. Sixteen of seventeen participants available for follow-up demonstrated a cosmetic improvement. This study was reported at a meeting in 1991. The study for the treatment ofglabellarfrown lines was published in 1992.[113]This result was subsequently confirmed by other groups (Brin, and the Columbia University group under Monte Keen[153]). The FDA announced regulatory approval of botulinum toxin type A (Botox Cosmetic) to temporarily improve the appearance of moderate-to-severe frown lines between the eyebrows (glabellar lines) in 2002 after extensive clinical trials.[154]Well before this, the cosmetic use of botulinum toxin type A became widespread.[155]The results of Botox Cosmetic can last up to four months and may vary with each patient.[156]The USFood and Drug Administration(FDA) approved an alternative product-safety testing method in response to increasing public concern thatLD50testing was required for each batch sold in the market.[157][158]

Botulinum toxin type-A has also been used in the treatment ofgummysmiles;[159]the material is injected into the hyperactive muscles of upper lip, which causes a reduction in the upward movement of lip thus resulting in a smile with a less exposure ofgingiva.[160]Botox is usually injected in the three lip elevator muscles that converge on the lateral side of the ala of the nose; thelevator labii superioris(LLS), thelevator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle(LLSAN), and thezygomaticus minor(ZMi).[161][162]

Upper motor neuron syndrome

[edit]Botulinum toxin type-A is now a common treatment for muscles affected by theupper motor neuronsyndrome (UMNS), such ascerebral palsy,[32]for muscles with an impaired ability to effectivelylengthen.Muscles affected by UMNS frequently are limited byweakness,loss ofreciprocal inhibition,decreased movement control, and hypertonicity (includingspasticity). In January 2014, Botulinum toxin was approved by UK'sMedicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency(MHRA) for the treatment of ankle disability due to lower limb spasticity associated with stroke in adults.[51]Joint motion may be restricted by severe muscle imbalance related to the syndrome, when some muscles are markedly hypertonic, and lack effective active lengthening. Injecting an overactive muscle to decrease its level of contraction can allow improved reciprocal motion, so improved ability to move and exercise.[32]

Sialorrhea

[edit]Sialorrheais a condition where oral secretions are unable to be eliminated, causing pooling of saliva in the mouth. This condition can be caused by various neurological syndromes such asBell's palsy,intellectual disability, and cerebral palsy. Injection of botulinum toxin type-A into salivary glands is useful in reducing the secretions.[163]

Cervical dystonia

[edit]Botulinum toxin type-A is used to treatcervical dystonia,but it can become ineffective after a time. Botulinum toxin type B received FDA approval for treatment of cervicaldystoniain December 2000. Brand names for botulinum toxin type-B include Myobloc in the United States and Neurobloc in the European Union.[137]

Chronic migraine

[edit]Onabotulinumtoxin A (trade name Botox) received FDA approval for treatment of chronicmigraineson 15 October 2010. The toxin is injected into the head and neck to treat these chronic headaches. Approval followed evidence presented to the agency from two studies funded by Allergan showing a very slight improvement in incidence of chronic migraines for those with migraines undergoing the Botox treatment.[164][165]

Since then, several randomized control trials have shown botulinum toxin type A to improve headache symptoms and quality of life when used prophylactically for participants with chronicmigraine[166]who exhibit headache characteristics consistent with: pressure perceived from outside source, shorter total duration of chronic migraines (<30 years), "detoxification" of participants with coexisting chronic daily headache due to medication overuse, and no current history of other preventive headache medications.[167]

Depression

[edit]A few small trials have found benefits in people withdepression.[168][169]Research is based on thefacial feedback hypothesis.[170]

Premature ejaculation

[edit]The drug for the treatment ofpremature ejaculationhas been under development since August 2013, and is inPhase IItrials.[169][171]

References

[edit]- ^abcdefg"Letybo- letibotulinumtoxina-wlbg injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution".DailyMed.5 August 2024.Retrieved5 September2024.

- ^abc"Letybo | Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA)".Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2022.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^ab"Nuceiva".Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).10 February 2023.Retrieved8 April2023.

- ^ab"Relfydess (relabotulinumtoxinA, purified Botulinum toxin type A)".Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).30 July 2024.Retrieved12 October2024.

- ^"FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)".nctr-crs.fda.gov.FDA.Retrieved22 October2023.

- ^"Nuceiva (PPD Australia Pty Ltd)".Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).16 February 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 18 March 2023.Retrieved8 April2023.

- ^"Nuceiva prabotulinumtoxinA 100 Units Powder for Solution for Injection vial (381094)".Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).26 January 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 8 April 2023.Retrieved8 April2023.

- ^"Prescription medicines: registration of new chemical entities in Australia, 2014".Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).21 June 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 10 April 2023.Retrieved10 April2023.

- ^"AusPAR: Letybo | Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA)".Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2024.Retrieved31 March2024.

- ^"Regulatory Decision Summary - Botox".Health Canada.23 October 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 12 June 2022.Retrieved12 June2022.

- ^"Regulatory Decision Summary - Nuceiva".Health Canada.23 October 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 7 June 2022.Retrieved11 June2022.

- ^"Regulatory Decision Summary for Xeomin".Drug and Health Products Portal.15 March 2022.Retrieved1 April2024.

- ^"Regulatory Decision Summary for Botox".Drug and Health Products Portal.7 February 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 2 April 2024.Retrieved2 April2024.

- ^"Health Canada New Drug Authorizations: 2016 Highlights".Health Canada.14 March 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2024.Retrieved7 April2024.

- ^"Azzalure - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)".(emc).16 August 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2022.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^"Alluzience, 200 Speywood units/ml, solution for injection - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)".(emc).2 October 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2022.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^"Letybo 50 units powder for solution for injection - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)".(emc).10 May 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2022.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^"Xeomin 50 units powder for solution for injection - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)".(emc).28 July 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2022.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^ab"Botox- onabotulinumtoxina injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution".DailyMed.30 July 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 2 June 2022.Retrieved12 June2022.

- ^"Botox Cosmetic- onabotulinumtoxina injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution".DailyMed.9 February 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2022.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^abc"Myobloc- rimabotulinumtoxinb injection, solution".DailyMed.22 March 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 2 June 2022.Retrieved12 June2022.

- ^"Dysport- botulinum toxin type a injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution".DailyMed.28 February 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 2 June 2022.Retrieved12 June2022.

- ^abcde"Daxxify- botulinum toxin type a injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution".DailyMed.19 September 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2022.Retrieved27 September2022.

- ^abcdefgMontecucco C, Molgó J (June 2005). "Botulinal neurotoxins: revival of an old killer".Current Opinion in Pharmacology.5(3): 274–279.doi:10.1016/j.coph.2004.12.006.PMID15907915.

- ^Figgitt DP, Noble S (2002). "Botulinum toxin B: a review of its therapeutic potential in the management of cervical dystonia".Drugs.62(4): 705–722.doi:10.2165/00003495-200262040-00011.PMID11893235.S2CID46981635.

- ^abcShukla HD, Sharma SK (2005). "Clostridium botulinum: a bug with beauty and weapon".Critical Reviews in Microbiology.31(1): 11–18.doi:10.1080/10408410590912952.PMID15839401.S2CID2855356.

- ^abJanes LE, Connor LM, Moradi A, Alghoul M (April 2021). "Current Use of Cosmetic Toxins to Improve Facial Aesthetics".Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.147(4): 644e–657e.doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000007762.PMID33776040.S2CID232408799.

- ^abAl-Ghamdi AS, Alghanemy N, Joharji H, Al-Qahtani D, Alghamdi H (January 2015)."Botulinum toxin: Non cosmetic and off-label dermatological uses".Journal of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery.19(1): 1–8.doi:10.1016/j.jdds.2014.06.002.

- ^Rosales RL, Bigalke H, Dressler D (February 2006). "Pharmacology of botulinum toxin: differences between type A preparations".European Journal of Neurology.13(Suppl 1): 2–10.doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01438.x.PMID16417591.S2CID32387953.

- ^ab"Botulism toxin X: Time to update the textbooks, thanks to genomic sequencing".Boston Children's Hospital. 7 August 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 14 September 2021.Retrieved28 October2019.

- ^abc"Study: Novel botulinum toxin less dangerous than thought".CIDRAP.University of Minnesota. 17 June 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 28 October 2019.Retrieved28 October2019.

- ^abcdefFarag SM, Mohammed MO, El-Sobky TA, ElKadery NA, ElZohiery AK (March 2020)."Botulinum Toxin A Injection in Treatment of Upper Limb Spasticity in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials".JBJS Reviews.8(3): e0119.doi:10.2106/JBJS.RVW.19.00119.PMC7161716.PMID32224633.

- ^abcdBlumetti FC, Belloti JC, Tamaoki MJ, Pinto JA (October 2019)."Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of lower limb spasticity in children with cerebral palsy".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2019(10): CD001408.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001408.pub2.PMC6779591.PMID31591703.

- ^American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (27 October 2011)."OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botulinum Toxin Type A) Monograph for Professionals".drugs.com.Archivedfrom the original on 6 September 2015.Retrieved4 March2015.

- ^abc"Fact sheets - Botulism".World Health Organization.10 January 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2019.Retrieved23 March2019.

- ^Košenina S, Masuyer G, Zhang S, Dong M, Stenmark P (June 2019)."Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of the Weissella oryzae botulinum-like toxin".FEBS Letters.593(12): 1403–1410.doi:10.1002/1873-3468.13446.PMID31111466.

- ^Dhaked RK, Singh MK, Singh P, Gupta P (November 2010)."Botulinum toxin: Bioweapon & magic drug".Indian Journal of Medical Research.132(5): 489–503.PMC3028942.PMID21149997.

- ^Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, et al. (February 2001). "Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: medical and public health management".JAMA.285(8): 1059–1070.doi:10.1001/jama.285.8.1059.PMID11209178.

- ^Ozcakir S, Sivrioglu K (June 2007)."Botulinum toxin in poststroke spasticity".Clinical Medicine & Research.5(2): 132–138.doi:10.3121/cmr.2007.716.PMC1905930.PMID17607049.

- ^Yan X, Lan J, Liu Y, Miao J (November 2018)."Efficacy and Safety of Botulinum Toxin Type A in Spasticity Caused by Spinal Cord Injury: A Randomized, Controlled Trial".Medical Science Monitor.24:8160–8171.doi:10.12659/MSM.911296.PMC6243868.PMID30423587.

- ^"Cervical dystonia - Symptoms and causes".Mayo Clinic. 28 January 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 12 December 2018.Retrieved14 October2015.

- ^Pacik PT (December 2009)."Botox treatment for vaginismus".Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.124(6): 455e–456e.doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bf7f11.PMID19952618.

- ^abcdFelber ES (October 2006). "Botulinum toxin in primary care medicine".The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association.106(10): 609–614.PMID17122031.S2CID245177279.

- ^Stavropoulos SN, Friedel D, Modayil R, Iqbal S, Grendell JH (March 2013)."Endoscopic approaches to treatment of achalasia".Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology.6(2): 115–135.doi:10.1177/1756283X12468039.PMC3589133.PMID23503707.

- ^Long H, Liao Z, Wang Y, Liao L, Lai W (February 2012)."Efficacy of botulinum toxins on bruxism: an evidence-based review".International Dental Journal.62(1): 1–5.doi:10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00085.x.PMC9374973.PMID22251031.

- ^Mangera A, Andersson KE, Apostolidis A, Chapple C, Dasgupta P, Giannantoni A, et al. (October 2011). "Contemporary management of lower urinary tract disease with botulinum toxin A: a systematic review of botox (onabotulinumtoxinA) and dysport (abobotulinumtoxinA)".European Urology.60(4): 784–795.doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2011.07.001.PMID21782318.

- ^Villalba H, Villalba S, Abbas MA (2007)."Anal fissure: a common cause of anal pain".The Permanente Journal.11(4): 62–65.doi:10.7812/tpp/07-072.PMC3048443.PMID21412485.

- ^Duthie JB, Vincent M, Herbison GP, Wilson DI, Wilson D (December 2011). Duthie JB (ed.). "Botulinum toxin injections for adults with overactive bladder syndrome".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(12): CD005493.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005493.pub3.PMID22161392.

- ^Scott AB (1994). "Change of eye muscle sarcomeres according to eye position".Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus.31(2): 85–88.doi:10.3928/0191-3913-19940301-05.PMID8014792.

- ^Simpson L (2 December 2012).Botulinum Neurotoxin and Tetanus Toxin.Elsevier.ISBN978-0-323-14160-4.Archivedfrom the original on 28 August 2021.Retrieved1 October2020.

- ^abUK Approves New Botox UseArchived22 February 2014 at theWayback Machine.dddmag.com. 4 February 2014

- ^"UK's MHRA approves Botox for treatment of ankle disability in stroke survivors".The Pharma Letter.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2020.Retrieved16 March2020.

- ^"FDA Approved Drug Products – Dysport".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA).Archivedfrom the original on 8 November 2016.Retrieved7 November2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^Pavone V, Testa G, Restivo DA, Cannavò L, Condorelli G, Portinaro NM, et al. (19 February 2016)."Botulinum Toxin Treatment for Limb Spasticity in Childhood Cerebral Palsy".Frontiers in Pharmacology.7:29.doi:10.3389/fphar.2016.00029.PMC4759702.PMID26924985.

- ^Syed YY (August 2017). "AbobotulinumtoxinA: A Review in Pediatric Lower Limb Spasticity".Paediatric Drugs.19(4): 367–373.doi:10.1007/s40272-017-0242-4.PMID28623614.S2CID24857218.

- ^Wittich CM, Burkle CM, Lanier WL (October 2012)."Ten common questions (and their answers) about off-label drug use".Mayo Clinic Proceedings.87(10): 982–990.doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.04.017.PMC3538391.PMID22877654.

- ^abOcampo VV, Foster CS (30 May 2012)."Infantile Esotropia Treatment & Management".Medscape.Archivedfrom the original on 28 November 2014.Retrieved6 April2014.

- ^abEisenach JH, Atkinson JL, Fealey RD (May 2005)."Hyperhidrosis: evolving therapies for a well-established phenomenon".Mayo Clinic Proceedings.80(5): 657–666.doi:10.4065/80.5.657.PMID15887434.

- ^"FDA Approves Botox to Treat Chronic Migraines".WebMD.Archivedfrom the original on 5 May 2017.Retrieved12 May2017.

- ^"HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION These highlights do not include all the information needed to use BOTOX® safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for BOTOX"(PDF).Accessdata.fda.gov.2011.Archived(PDF)from the original on 16 February 2024.Retrieved27 April2024.

- ^Satriyasa BK (10 April 2019)."Botulinum toxin (Botox) A for reducing the appearance of facial wrinkles: a literature review of clinical use and pharmacological aspect".Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology.12:223–228.doi:10.2147/CCID.S202919.PMC6489637.PMID31114283.

- ^abcdeSmall R (August 2014). "Botulinum toxin injection for facial wrinkles".American Family Physician.90(3): 168–175.PMID25077722.

- ^abKrause R (10 June 2019)."Jeuveau, The Most Affordable Wrinkle Injectable".refinery29.com.Archivedfrom the original on 18 March 2021.Retrieved9 July2019.

- ^abcdefg"Drug Trials Snapshot: Daxxify".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA).7 September 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2024.Retrieved23 March2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^"Revance Announces FDA Approval of Daxxify (DaxibotulinumtoxinA-lanm) for Injection, the First and Only Peptide-Formulated Neuromodulator With Long-Lasting Results"(Press release). Revance. 8 September 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2022.Retrieved24 September2022– via Business Wire.

- ^abcdef"Drug Trials Snapshots: Letybo".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA).29 February 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2024.Retrieved23 March2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^"Novel Drug Approvals for 2024".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA).29 April 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 30 April 2024.Retrieved30 April2024.

- ^Mittal SO, Safarpour D, Jabbari B (February 2016). "Botulinum Toxin Treatment of Neuropathic Pain".Seminars in Neurology.36(1): 73–83.doi:10.1055/s-0036-1571953.PMID26866499.S2CID41120474.

- ^Charles PD (November 2004)."Botulinum neurotoxin serotype A: a clinical update on non-cosmetic uses".American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy.61(22 Suppl 6): S11–S23.doi:10.1093/ajhp/61.suppl_6.S11.PMID15598005.

- ^Singh JA, Fitzgerald PM (September 2010). "Botulinum toxin for shoulder pain".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(9): CD008271.doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008271.pub2.PMID20824874.

- ^abNigam PK, Nigam A (2010)."Botulinum toxin".Indian Journal of Dermatology.55(1): 8–14.doi:10.4103/0019-5154.60343.PMC2856357.PMID20418969.

- ^abcdCoté TR, Mohan AK, Polder JA, Walton MK, Braun MM (September 2005)."Botulinum toxin type A injections: adverse events reported to the US Food and Drug Administration in therapeutic and cosmetic cases".Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.53(3): 407–415.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.06.011.PMID16112345.Archivedfrom the original on 23 May 2022.Retrieved29 December2021.

- ^Witmanowski H, Błochowiak K (December 2020)."The whole truth about botulinum toxin - a review".Postepy Dermatologii I Alergologii.37(6): 853–861.doi:10.5114/ada.2019.82795.PMC7874868.PMID33603602.

- ^Witmanowski H, Błochowiak K (December 2020)."The whole truth about botulinum toxin - a review".Postepy Dermatologii I Alergologii.37(6): 853–861.doi:10.5114/ada.2019.82795.PMC7874868.PMID33603602.

- ^Hamman MS, Goldman MP (August 2013)."Minimizing bruising following fillers and other cosmetic injectables".The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology.6(8): 16–18.PMC3760599.PMID24003345.

- ^Schiffer J (8 April 2021)."How Barely-There Botox Became the Norm".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Archivedfrom the original on 28 December 2021.Retrieved23 November2021.

- ^"FDA Notifies Public of Adverse Reactions Linked to Botox Use".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 8 February 2008. Archived fromthe originalon 2 March 2012.Retrieved6 May2012.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^ab"FDA Gives Update on Botulinum Toxin Safety Warnings; Established Names of Drugs Changed".Pharmaceutical Online.4 August 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 6 July 2019.Retrieved16 July2019.

- ^"FDA Gives Update on Botulinum Toxin Safety Warnings; Established Names of Drugs Changed"(Press release). U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 3 August 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 24 September 2015.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^"Update of Safety Review of OnabotulinumtoxinA (marketed as Botox/Botox Cosmetic), AbobotulinumtoxinA (marketed as Dysport) and RimabotulinumtoxinB (marketed as Myobloc)".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 3 August 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 1 July 2015.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^"Follow-up to the February 8, 2008, Early Communication about an Ongoing Safety Review of Botox and Botox Cosmetic (Botulinum toxin Type A) and Myobloc (Botulinum toxin Type B)".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 8 February 2008. Archived fromthe originalon 2 June 2015.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^abcd"OnabotulinumtoxinA (marketed as Botox/Botox Cosmetic), AbobotulinumtoxinA (marketed as Dysport) and RimabotulinumtoxinB (marketed as Myobloc) Information".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 3 November 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2022.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^ab"Information for Healthcare Professionals: OnabotulinumtoxinA (marketed as Botox/Botox Cosmetic), AbobotulinumtoxinA (marketed as Dysport) and RimabotulinumtoxinB (marketed as Myobloc)".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 13 September 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 13 September 2015.Retrieved1 September2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^"Botox chemical may spread, Health Canada confirms".CBC News.13 January 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 21 February 2009.

- ^"Kinds of Botulism".U.S.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC).Archivedfrom the original on 5 October 2016.Retrieved4 October2016.

- ^abcd"Botulism – Diagnosis and Treatment".U.S.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC).Archivedfrom the original on 5 October 2016.Retrieved5 October2016.

- ^"Botulism - Diagnosis and treatment".Mayo Clinic.Archivedfrom the original on 1 November 2023.Retrieved1 November2023.

- ^Barash JR, Arnon SS (January 2014). "A novel strain of Clostridium botulinum that produces type B and type H botulinum toxins".The Journal of Infectious Diseases.209(2): 183–191.doi:10.1093/infdis/jit449.PMID24106296.

- ^abBarr JR, Moura H, Boyer AE, Woolfitt AR, Kalb SR, Pavlopoulos A, et al. (October 2005)."Botulinum neurotoxin detection and differentiation by mass spectrometry".Emerging Infectious Diseases.11(10): 1578–1583.doi:10.3201/eid1110.041279.PMC3366733.PMID16318699.

- ^abDressler D, Saberi FA, Barbosa ER (March 2005)."Botulinum toxin: mechanisms of action".Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria.63(1): 180–185.doi:10.1159/000083259.PMID15830090.S2CID16307223.

- ^abDong M, Masuyer G, Stenmark P (June 2019)."Botulinum and Tetanus Neurotoxins".Annual Review of Biochemistry.88(1): 811–837.doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111654.PMC7539302.PMID30388027.

- ^abcdeLi B, Peet NP, Butler MM, Burnett JC, Moir DT, Bowlin TL (December 2010)."Small molecule inhibitors as countermeasures for botulinum neurotoxin intoxication".Molecules.16(1): 202–220.doi:10.3390/molecules16010202.PMC6259422.PMID21193845.

- ^Hill KK, Smith TJ (2013). "Genetic diversity within Clostridium botulinum serotypes, botulinum neurotoxin gene clusters and toxin subtypes". In Rummel A, Binz T (eds.).Botulinum Neurotoxins.Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 364. Springer. pp. 1–20.doi:10.1007/978-3-642-33570-9_1.ISBN978-3-642-33569-3.PMID23239346.

- ^abDavies JR, Liu SM, Acharya KR (October 2018)."Variations in the Botulinum Neurotoxin Binding Domain and the Potential for Novel Therapeutics".Toxins.10(10): 421.doi:10.3390/toxins10100421.PMC6215321.PMID30347838.

- ^Brunt J, Carter AT, Stringer SC, Peck MW (February 2018)."Identification of a novel botulinum neurotoxin gene cluster in Enterococcus".FEBS Letters.592(3): 310–317.doi:10.1002/1873-3468.12969.PMC5838542.PMID29323697.

- ^abcdErbguth FJ (March 2004). "Historical notes on botulism, Clostridium botulinum, botulinum toxin, and the idea of the therapeutic use of the toxin".Movement Disorders.19(Supplement 8): S2–S6.doi:10.1002/mds.20003.PMID15027048.S2CID8190807.

- ^abErbguth FJ, Naumann M (November 1999). "Historical aspects of botulinum toxin: Justinus Kerner (1786-1862) and the" sausage poison "".Neurology.53(8): 1850–1853.doi:10.1212/wnl.53.8.1850.PMID10563638.S2CID46559225.

- ^abcMonheit GD, Pickett A (May 2017)."AbobotulinumtoxinA: A 25-Year History".Aesthetic Surgery Journal.37(suppl_1): S4–S11.doi:10.1093/asj/sjw284.PMC5434488.PMID28388718.

- ^Pellett S (June 2012). "Learning from the past: historical aspects of bacterial toxins as pharmaceuticals".Current Opinion in Microbiology.15(3): 292–299.doi:10.1016/j.mib.2012.05.005.PMID22651975.

- ^"Home Canning and Botulism".24 June 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 2 August 2022.Retrieved3 August2022.

- ^Lamanna C, McELROY OE, Eklund HW (May 1946). "The purification and crystallization of Clostridium botulinum type A toxin".Science.103(2681): 613–614.Bibcode:1946Sci...103..613L.doi:10.1126/science.103.2681.613.PMID21026141.

- ^Burgen AS, Dickens F, Zatman LJ (August 1949)."The action of botulinum toxin on the neuro-muscular junction".The Journal of Physiology.109(1–2): 10–24.doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004364.PMC1392572.PMID15394302.

- ^Magoon E, Cruciger M, Scott AB, Jampolsky A (May 1982). "Diagnostic injection of Xylocaine into extraocular muscles".Ophthalmology.89(5): 489–491.doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(82)34764-8.PMID7099568.

- ^Drachman DB (August 1964). "Atrophy of Skeletal Muscle in Chick Embryos Treated with Botulinum Toxin".Science.145(3633): 719–721.Bibcode:1964Sci...145..719D.doi:10.1126/science.145.3633.719.PMID14163805.S2CID43093912.

- ^Scott AB, Rosenbaum A, Collins CC (December 1973). "Pharmacologic weakening of extraocular muscles".Investigative Ophthalmology.12(12): 924–927.PMID4203467.

- ^Scott AB (October 1980). "Botulinum toxin injection into extraocular muscles as an alternative to strabismus surgery".Ophthalmology.87(10): 1044–1049.doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35127-0.PMID7243198.S2CID27341687.

- ^abBoffey PM (14 October 1986)."Loss Of Drug Relegates Many To Blindness Again".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2011.Retrieved14 July2010.

- ^ab"Re: Docket No. FDA-2008-P-0061"(PDF).U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 30 April 2009. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 July 2010.Retrieved26 July2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^Wellman-Labadie O, Zhou Y (May 2010). "The US Orphan Drug Act: rare disease research stimulator or commercial opportunity?".Health Policy.95(2–3): 216–228.doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.12.001.PMID20036435.

- ^abClark RP, Berris CE (August 1989). "Botulinum toxin: a treatment for facial asymmetry caused by facial nerve paralysis".Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.84(2): 353–355.doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000205566.47797.8d.PMID2748749.

- ^abRohrich RJ, Janis JE, Fagien S, Stuzin JM (October 2003). "The cosmetic use of botulinum toxin".Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.112(5 Suppl): 177S–188S.doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000082208.37239.5b.PMID14504502.

- ^Carruthers A (November–December 2003). "History of the clinical use of botulinum toxin A and B".Clinics in Dermatology.21(6): 469–472.doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2003.11.003.PMID14759577.

- ^abCarruthers JD, Carruthers JA (January 1992). "Treatment of glabellar frown lines with C. botulinum-A exotoxin".The Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology.18(1): 17–21.doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb03295.x.PMID1740562.

- ^Binder WJ, Brin MF, Blitzer A, Schoenrock LD, Pogoda JM (December 2000). "Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) for treatment of migraine headaches: an open-label study".Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.123(6): 669–676.doi:10.1067/mhn.2000.110960.PMID11112955.S2CID24406607.

- ^Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Hayashino Y (April 2012). "Botulinum toxin A for prophylactic treatment of migraine and tension headaches in adults: a meta-analysis".JAMA.307(16): 1736–1745.doi:10.1001/jama.2012.505.PMID22535858.

- ^Ramachandran R, Yaksh TL (September 2014)."Therapeutic use of botulinum toxin in migraine: mechanisms of action".British Journal of Pharmacology.171(18): 4177–4192.doi:10.1111/bph.12763.PMC4241086.PMID24819339.

- ^"New plastic surgery statistics reveal trends toward body enhancement".Plastic Surgery.11 March 2019. Archived fromthe originalon 12 March 2019.

- ^Chapman L (10 May 2012)."The global botox market forecast to reach $2.9 billion by 2018".Archived fromthe originalon 6 August 2012.Retrieved5 October2012.

- ^"2020 National Plastic Surgery Statistics: Cosmetic Surgical Procedures"(PDF).American Society of Plastic Surgeons.Archived(PDF)from the original on 23 June 2021.Retrieved22 May2021.

- ^"Botulinum Toxin Market".Fortune Business Insights.Archivedfrom the original on 27 June 2021.Retrieved22 May2021.

- ^"How Much Does Botox Cost".American Cosmetic Association.Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2023.Retrieved13 March2013.

- ^"Medicare Guidelines for Botox Treatments".MedicareFAQ.com.27 September 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 23 May 2021.Retrieved22 May2021.

- ^"BOTOX (onabotulinumtoxinA) for injection, for intramuscular, intradetrusor, or intradermal use"(PDF).Highlights of Prescribing Information.U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA).Archived(PDF)from the original on 28 March 2021.Retrieved22 May2021.

- ^"Botox Procedures: What is Botox & How Does it Work".The American Academy of Facial Esthetics.Archivedfrom the original on 22 May 2021.Retrieved22 May2021.

- ^Koirala J, Basnet S (14 July 2004)."Botulism, Botulinum Toxin, and Bioterrorism: Review and Update".Medscape.Cliggott Publishing. Archived fromthe originalon 1 June 2011.Retrieved14 July2010.

- ^Public Health Agency of Canada (19 April 2011)."Pathogen Safety Data Sheets: Infectious Substances –Clostridium botulinum".Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2022.Retrieved24 January2022.

- ^Fleisher LA, Roizen MF, Roizen J (31 May 2017).Essence of Anesthesia Practice E-Book.Elsevier Health Sciences.ISBN978-0-323-39541-0.Archivedfrom the original on 11 November 2021.Retrieved10 June2022.

- ^"M8 Paper"(PDF).U.S. Army.Archived(PDF)from the original on 23 October 2020.Retrieved16 September2020.

M8 paper is a chemically-treated, dye-impregnated paper used to detect liquid substances for the presence of V- and G-type nerve agents and H- and L-type blister agents.

- ^Baselt RC (2014).Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man.Seal Beach, Ca.: Biomedical Publications. pp. 260–61.ISBN978-0-9626523-9-4.

- ^McAdams D, Kornblet S (2011). "Baader-Meinhof Group (OR Baader-Meinhof Gang". In Pilch RF, Zilinskas RA (eds.).Encyclopedia of Bioterrorism Defense.Wiley-Liss. pp. 1–2.doi:10.1002/0471686786.ebd0012.pub2.ISBN978-0-471-68678-1.

- ^"Botulinum Toxin Type A Product Approval Information - Licensing Action 4/12/02".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 9 February 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 13 January 2017.Retrieved18 December2022.

- ^"Drug Approval Package: Dysport (abobotulinumtoxin) NDA #125274s000".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 17 August 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 24 November 2019.Retrieved23 November2019.

- ^"Hugel's 'Letybo' First in Korea to Obtain Marketing Approval from Australia".Hugel(Press release). 24 November 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2022.Retrieved18 December2022– via PR Newswire.

- ^"Drug Approval Package: Xeomin (incobotulinumtoxinA) Injection NDA #125360".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 24 December 1999.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2020.Retrieved23 November2019.

- ^"Drug Approval Package: Jeuveau".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 5 March 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 23 November 2019.Retrieved22 November2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^"2011 Allergan Annual Report"(PDF).Allergan.Archived(PDF)from the original on 15 November 2012.Retrieved3 May2012.See PDF p. 7.

- ^abcWalker TJ, Dayan SH (February 2014)."Comparison and overview of currently available neurotoxins".The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology.7(2): 31–39.PMC3935649.PMID24587850.

- ^"Botulinum Toxin Type A".Hugh Source (International) Limited.Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2008.Retrieved14 July2010.

- ^Petrou I (Spring 2009)."Medy-Tox Introduces Neuronox to the Botulinum Toxin Arena"(PDF).The European Aesthetic Guide.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 20 March 2013.Retrieved9 December2009.

- ^Schantz EJ, Johnson EA (March 1992)."Properties and use of botulinum toxin and other microbial neurotoxins in medicine".Microbiological Reviews.56(1): 80–99.doi:10.1128/MMBR.56.1.80-99.1992.PMC372855.PMID1579114.

- ^abcd"About Botulism".U.S.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC).9 October 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2020.Retrieved13 May2020.

- ^Poulain B, Popoff MR (January 2019)."Why Are Botulinum Neurotoxin-Producing Bacteria So Diverse and Botulinum Neurotoxins So Toxic?".Toxins.11(1): 34.doi:10.3390/toxins11010034.PMC6357194.PMID30641949.

- ^Hill KK, Xie G, Foley BT, Smith TJ, Munk AC, Bruce D, et al. (October 2009)."Recombination and insertion events involving the botulinum neurotoxin complex genes in Clostridium botulinum types A, B, E and F and Clostridium butyricum type E strains".BMC Biology.7(1): 66.doi:10.1186/1741-7007-7-66.PMC2764570.PMID19804621.

- ^"Botulism".U.S.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC).19 August 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2016.Retrieved28 August2019.

- ^"Clostridium botulinum Toxin Formation"(PDF).U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA).29 March 2011. p. 246.Archived(PDF)from the original on 8 February 2021.Retrieved12 March2023.

- ^Licciardello JJ, Nickerson JT, Ribich CA, Goldblith SA (March 1967)."Thermal inactivation of type E botulinum toxin".Applied Microbiology.15(2): 249–256.doi:10.1128/AEM.15.2.249-256.1967.PMC546888.PMID5339838.

- ^Setlow P (April 2007). "I will survive: DNA protection in bacterial spores".Trends in Microbiology.15(4): 172–180.doi:10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.004.PMID17336071.

- ^Capková K, Salzameda NT, Janda KD (October 2009)."Investigations into small molecule non-peptidic inhibitors of the botulinum neurotoxins".Toxicon.54(5): 575–582.Bibcode:2009Txcn...54..575C.doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.03.016.PMC2730986.PMID19327377.

- ^Flanders M, Tischler A, Wise J, Williams F, Beneish R, Auger N (June 1987). "Injection of type A botulinum toxin into extraocular muscles for correction of strabismus".Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. Journal Canadien d'Ophtalmologie.22(4): 212–217.PMID3607594.

- ^"Botulinum toxin therapy of eye muscle disorders. Safety and effectiveness. American Academy of Ophthalmology".Ophthalmology.Suppl (Suppl 37-41): 37–41. September 1989.doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32989-7.PMID2779991.

- ^Hellman A, Torres-Russotto D (March 2015)."Botulinum toxin in the management of blepharospasm: current evidence and recent developments".Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders.8(2): 82–91.doi:10.1177/1756285614557475.PMC4356659.PMID25922620.

- ^Koudsie S, Coste-Verdier V, Paya C, Chan H, Andrebe C, Pechmeja J, et al. (April 2021). "[Long term outcomes of botulinum toxin injections in infantile esotropia]".Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie.44(4): 509–518.doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2020.07.023.PMID33632627.S2CID232058260.

- ^Keen M, Kopelman JE, Aviv JE, Binder W, Brin M, Blitzer A (April 1994). "Botulinum toxin A: a novel method to remove periorbital wrinkles".Facial Plastic Surgery.10(2): 141–146.doi:10.1055/s-2008-1064563.PMID7995530.S2CID29006338.

- ^"Botulinum Toxin Type A Product Approval Information – Licensing Action 4/12/02".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 29 October 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 8 March 2010.Retrieved26 July2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^Giesler M (2012). "How Doppelgänger Brand Images Influence the Market Creation Process: Longitudinal Insights from the Rise of Botox Cosmetic".Journal of Marketing.76(6): 55–68.doi:10.1509/jm.10.0406.S2CID167319134.

- ^"Botox Cosmetic (onabotulinumtoxinA) Product Information".Allergan.22 January 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 21 July 2021.Retrieved1 March2018.

- ^"Allergan Receives FDA Approval for First-of-Its-Kind, Fully in vitro, Cell-Based Assay for Botox and Botox Cosmetic (onabotulinumtoxinA)".Allergan. 24 June 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 26 June 2011.Retrieved26 June2011.

- ^"In U.S., Few Alternatives To Testing On Animals".The Washington Post.12 April 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 12 November 2012.Retrieved26 June2011.

- ^Nayyar P, Kumar P, Nayyar PV, Singh A (December 2014)."BOTOX: Broadening the Horizon of Dentistry".Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research.8(12): ZE25–ZE29.doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/11624.5341.PMC4316364.PMID25654058.

- ^Hwang WS, Hur MS, Hu KS, Song WC, Koh KS, Baik HS, et al. (January 2009)."Surface anatomy of the lip elevator muscles for the treatment of gummy smile using botulinum toxin".The Angle Orthodontist.79(1): 70–77.doi:10.2319/091407-437.1.PMID19123705.

- ^Gracco A, Tracey S (May 2010). "Botox and the gummy smile".Progress in Orthodontics.11(1): 76–82.doi:10.1016/j.pio.2010.04.004.PMID20529632.

- ^Mazzuco R, Hexsel D (December 2010). "Gummy smile and botulinum toxin: a new approach based on the gingival exposure area".Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.63(6): 1042–1051.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.053.PMID21093661.

- ^Khan WU, Campisi P, Nadarajah S, Shakur YA, Khan N, Semenuk D, et al. (April 2011)."Botulinum toxin A for treatment of sialorrhea in children: an effective, minimally invasive approach".Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.137(4): 339–344.doi:10.1001/archoto.2010.240.PMID21242533.

- ^"FDA approves Botox to treat chronic migraine"(Press release). U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA). 19 October 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 19 October 2010.Retrieved23 November2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^Watkins T (15 October 2010)."FDA approves Botox as migraine preventative".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2020.Retrieved16 October2010.

- ^Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, Aurora SK, Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, et al. (June 2010). "OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program".Headache.50(6): 921–936.doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01678.x.PMID20487038.S2CID9621285.

- ^Ashkenazi A (March 2010). "Botulinum toxin type a for chronic migraine".Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports.10(2): 140–146.doi:10.1007/s11910-010-0087-5.PMID20425239.S2CID32191932.

- ^Magid M, Keeling BH, Reichenberg JS (November 2015). "Neurotoxins: Expanding Uses of Neuromodulators in Medicine--Major Depressive Disorder".Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.136(5 Suppl): 111S–119S.doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000001733.PMID26441090.S2CID24196194.

- ^ab"Onabotulinum toxin A - Allergan - AdisInsight".Archivedfrom the original on 30 October 2017.Retrieved5 September2017.

- ^Finzi E, Rosenthal NE (May 2014). "Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial".Journal of Psychiatric Research.52:1–6.doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.11.006.PMID24345483.

- ^Clinical trial numberNCT01917006for "An Exploratory Study of the Safety and Efficacy of Botox for the Treatment of Premature Ejaculation" atClinicalTrials.gov

Further reading

[edit]- Carruthers JD, Fagien S, Joseph JH, Humphrey SD, Biesman BS, Gallagher CJ, et al. (January 2020)."DaxibotulinumtoxinA for Injection for the Treatment of Glabellar Lines: Results from Each of Two Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Studies (SAKURA 1 and SAKURA 2)".Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.145(1): 45–58.doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006327.PMC6940025.PMID31609882.

- Solish N, Carruthers J, Kaufman J, Rubio RG, Gross TM, Gallagher CJ (December 2021)."Overview of DaxibotulinumtoxinA for Injection: A Novel Formulation of Botulinum Toxin Type A".Drugs.81(18): 2091–2101.doi:10.1007/s40265-021-01631-w.PMC8648634.PMID34787840.

External links

[edit]- Overview of all the structural information available in thePDBforUniProt:P0DPI1(Botulinum neurotoxin type A) at thePDBe-KB.

- Overview of all the structural information available in thePDBforUniProt:P10844(Botulinum neurotoxin type B) at thePDBe-KB.

- Overview of all the structural information available in thePDBforUniProt:A0A0X1KH89(Bontoxilysin A) at thePDBe-KB.

- "AbobotulinumtoxinA Injection".MedlinePlus.

- "IncobotulinumtoxinA Injection".MedlinePlus.

- "OnabotulinumtoxinA Injection".MedlinePlus.

- "PrabotulinumtoxinA-xvfs Injection".MedlinePlus.

- "RimabotulinumtoxinB Injection".MedlinePlus.