Breakup of Yugoslavia

| Part of theCold War,theRevolutions of 1989and theYugoslav Wars | |

Animated series of maps showing the breakup of theSFR Yugoslaviaand subsequent developments, from 1989 through 2008. The colors represent the different areas of control.

| |

| Date | 25 June 1991 – 27 April 1992 (10 months and 2 days) |

|---|---|

| Location | Unrecognized breakaway states: |

| Outcome |

|

After a period of political and economic crisis in the 1980s, the constituent republics of theSocialist Federal Republic of Yugoslaviasplit apart, but the unresolved issues caused a series of inter-ethnicYugoslav Wars.The wars primarilyaffected Bosnia and Herzegovina,neighbouring parts ofCroatiaand, some years later,Kosovo.

After theAlliedvictory inWorld War II,Yugoslavia was set up as a federation of six republics, with borders drawn along ethnic and historical lines:Bosnia and Herzegovina,Croatia,Macedonia,Montenegro,Serbia,andSlovenia.In addition, two autonomous provinces were established within Serbia:VojvodinaandKosovo.Each of the republics had its own branch of theLeague of Communists of Yugoslaviaparty and a ruling elite, and any tensions were solved on the federal level. The Yugoslav model of state organisation, as well as a "middle way" betweenplannedandliberal economy,had been a relative success, and the country experienced a period of strong economic growth and relative political stability up to the 1980s, underJosip Broz Tito.[1]After his death in 1980, the weakened system of federal government was left unable to cope with rising economic and political challenges.

In the 1980s,Kosovo Albaniansstarted to demand that their autonomous province be granted the status of a full constituent republic, starting with the1981 protests.Ethnic tensions between Albanians andKosovo Serbsremained high over the whole decade, which resulted in the growth of Serb opposition to the high autonomy of provinces and ineffective system of consensus at the federal level across Yugoslavia, which were seen as an obstacle for Serb interests. In 1987,Slobodan Miloševićcame to power in Serbia, and through a series of populist moves acquiredde factocontrol over Kosovo, Vojvodina, and Montenegro, garnering a high level of support among Serbs for hiscentralistpolicies. Milošević was met with opposition by party leaders of the western constituent republics of Slovenia and Croatia, who also advocated greater democratisation of the country in line with theRevolutions of 1989inEastern Europe.The League of Communists of Yugoslavia dissolved in January 1990 along federal lines. Republican communist organisations became the separate socialist parties.

During 1990, the socialists (former communists) lost power toethnic separatistparties in thefirst multi-party electionsheld across the country, except inMontenegroand inSerbia,where Milošević and his allies won. Nationalist rhetoric on all sides became increasingly heated. Between June 1991 and April 1992, four constituent republics declared independence while Montenegro and Serbia remained federated.Germanytook the initiative and recognized the independence of Croatia and Slovenia, but the status of ethnic Serbs outside Serbia and Montenegro, and that of ethnic Croats outside Croatia, remained unsolved. After a string of inter-ethnic incidents, theYugoslav Warsensued, firstin Croatiaand then, most severely, in multi-ethnicBosnia and Herzegovina.The wars left economic and political damage in the region that is still felt decades later.[2]On April 27, 1992, the Federal Council of the Assembly of the SFRY, based on the decision of theAssemblyof the Republic of Serbia and theAssemblyof Montenegro, adopted theConstitution of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia,which formally ended the breakup.

Background

[edit]Yugoslavia occupied a significant portion of theBalkan Peninsula,including a strip of land on the east coast of theAdriatic Sea,stretching southward from theBay of Triestein Central Europe to the mouth ofBojanaas well asLake Prespainland, and eastward as far as theIron Gateson theDanubeandMidžorin theBalkan Mountains,thus including a large part ofSoutheast Europe,a region with a history of ethnic conflict.

The important elements that fostered the discord involved contemporary and historical factors, including the formation of theKingdom of Yugoslavia,the first breakup and subsequent inter-ethnic and political wars and genocide duringWorld War II,ideas ofGreater Albania,Greater CroatiaandGreater Serbiaand conflicting views aboutPan-Slavism,and the unilateral recognition by a newly reunited Germany of the breakaway republics.

BeforeWorld War II,major tensions arose from the first,monarchist Yugoslavia's multi-ethnic make-up and relative political and demographic domination of the Serbs. Fundamental to the tensions were the different concepts of the new state. TheCroatsandSlovenesenvisaged afederalmodel where they would enjoy greater autonomy than they had as a separatecrown landunderAustria-Hungary.Under Austria-Hungary, both Slovenes and Croats enjoyed autonomy with free hands only in education, law, religion, and 45% of taxes.[3]The Serbs tended to view the territories as a just reward for their support of the allies inWorld War Iand the new state as an extension of theKingdom of Serbia.[4]

Tensions between the Croats and Serbs often erupted into open conflict, with the Serb-dominated security structure exercising oppression during elections and the assassination in theNational Assemblyof Croat political leaders, includingStjepan Radić,who opposed the Serbian monarch'sabsolutism.[5]The assassination and human rights abuses were subject of concern for theHuman Rights Leagueand precipitated voices of protest from intellectuals, includingAlbert Einstein.[6]It was in this environment of oppression that the radical insurgent group (later fascist dictatorship) theUstašewere formed.

During World War II, the country's tensions were exploited by the occupyingAxis forceswhich established a Croatpuppet statespanning much of present-dayCroatiaandBosnia and Herzegovina.The Axis powers installed theUstašeas the leaders of theIndependent State of Croatia.

The Ustaše resolved that the Serbian minority were afifth columnof Serbian expansionism and pursued a policy of persecution against the Serbs. The policy dictated that one-third of the Serbian minority were to be killed, one-third expelled, and one-third converted toCatholicismand assimilated as Croats. Conversely, Serbian RoyalistChetnikspursued their own campaign of persecution against non-Serbs in parts ofBosnia and Herzegovina,CroatiaandSandžakper theMoljević plan( "On Our State and Its Borders" ) and theordersissues byDraža Mihailovićwhich included "[t]he cleansing of all nation understandings and fighting".

Both Croats and Muslims were recruited as soldiers by theSS(primarily in the13thWaffenMountain Division). At the same time, former royalist, GeneralMilan Nedić,was installed by the Axis as head of thepuppet governmentin the German-occupied area of Serbia, and local Serbs were recruited into theGestapoand theSerbian Volunteer Corps,which was linked to the GermanWaffen-SS.Bothquislingswere confronted and eventually defeated by the communist-led, anti-fascistPartisanmovement composed of members of all ethnic groups in the area, leading to the formation of theSocialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

The official Yugoslav post-war estimate ofvictimsin Yugoslavia duringWorld War IIwas 1,704,000. Subsequent data gathering in the 1980s by historiansVladimir ŽerjavićandBogoljub Kočovićshowed that the actual number of dead was about 1 million. Of that number, 330,000 to 390,000 ethnic Serbs perished from all causes in Croatia and Bosnia.[7]These same historians also established the deaths of 192,000 to 207,000 ethnic Croats and 86,000 to 103,000 Muslims from all affiliations and causes throughout Yugoslavia.[8][full citation needed][9]

Prior to its collapse, Yugoslavia was a regional industrial power and an economic success. From 1960 to 1980, annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 6.1 percent, medical care was free, literacy was 91 percent, and life expectancy was 72 years.[10]Prior to 1991, Yugoslavia's armed forces were amongst the best-equipped in Europe.[11]

Yugoslavia was a unique state, straddling both the East and West. Moreover, its president,Josip Broz Tito,was one of the fundamental founders of the "third world"or"group of 77"which acted as an alternative to the superpowers. More importantly, Yugoslavia acted as abuffer statebetween the West and theSoviet Unionand also prevented the Soviets from getting a toehold on theMediterranean Sea.

The central government's control began to be loosened due to increasing nationalist grievances and the Communist's Party's wish to support "nationalself determination".This resulted in Kosovo being turned into an autonomous region of Serbia, legislated by the1974 constitution.This constitution broke down powers between the capital and the autonomous regions inVojvodina(an area of Yugoslavia with a large number of ethnic minorities) and Kosovo (with a large ethnic-Albanianpopulation).

Despite the federal structure of the newYugoslavia,there was still tension between the federalists, primarily Croats and Slovenes who argued for greater autonomy, andunitarists,primarily Serbs. The struggle would occur in cycles of protests for greater individual and national rights (such as theCroatian Spring) and subsequent repression. The 1974 constitution was an attempt to short-circuit this pattern by entrenching the federal model and formalising national rights.

The loosened control basically turned Yugoslavia into ade factoconfederacy,which also placed pressure on the legitimacy of the regime within the federation. Since the late 1970s a widening gap of economic resources between the developed and underdeveloped regions of Yugoslavia severely deteriorated the federation's unity.[12]The most developed republics, Croatia and Slovenia, rejected attempts to limit their autonomy as provided in the 1974 Constitution.[12]Public opinion in Slovenia in 1987 saw better economic opportunity in independence from Yugoslavia than within it.[12]There were also places that saw no economic benefit from being in Yugoslavia; for example, the autonomous province of Kosovo was poorly developed, and per capita GDP fell from 47 percent of the Yugoslav average in the immediate post-war period to 27 percent by the 1980s.[13]It highlighted the vast differences in the quality of life in the different republics.

Economic growth was curbed due to Western trade barriers combined with the1973 oil crisis.Yugoslavia subsequently fell into heavy IMF debt due to the large number ofInternational Monetary Fund(IMF) loans taken out by the regime. As a condition of receiving loans, the IMF demanded the "market liberalisation"of Yugoslavia. By 1981, Yugoslavia had incurred $19.9 billion in foreign debt. Another concern was the level of unemployment, at 1 million by 1980. This problem was compounded by the general" unproductiveness of the South ", which not only added to Yugoslavia's economic woes, but also irritated Slovenia and Croatia further.[14][15]

Causes

[edit]Structural problems

[edit]TheSFR Yugoslaviawas a conglomeration of eight federated entities, roughly divided along ethnic lines, including six republics:

Two autonomous provinces within Serbia:

With the1974 Constitution,the office ofPresident of Yugoslaviawas replaced with theYugoslav Presidency,an eight-membercollective head-of-statecomposed of representatives from six republics and, controversially, two autonomous provinces of theSocialist Republic of Serbia,SAP KosovoandSAP Vojvodina.

Since the SFR Yugoslav federation was formed in 1945, the constituent Socialist Republic of Serbia (SR Serbia) included the two autonomous provinces of SAP Kosovo and SAP Vojvodina. With the 1974 constitution, the influence of the central government of SR Serbia over the provinces was greatly reduced, which gave them long-sought autonomy. The government of SR Serbia was restricted in making and carrying out decisions that would apply to the provinces. The provinces had a vote in the Yugoslav Presidency, which was not always cast in favor of SR Serbia. In Serbia, there was great resentment towards these developments, which the nationalist elements of the public saw as the "division of Serbia". The 1974 constitution not only exacerbated Serbian fears of a "weak Serbia, for a strong Yugoslavia" but also hit at the heart of Serbian national sentiment. A majority of Serbs saw – and still see – Kosovo as the "cradle of the nation", and would not accept the possibility of losing it to the majority Albanian population.

In an effort to ensure his legacy, Tito's 1974 constitution established a system of year-long presidencies, on a rotation basis out of the eight leaders of the republics and autonomous provinces. Tito's death would show that such short terms were highly ineffective. Essentially it left a power vacuum which was left open for most of the 1980s. In their bookFree to Choose(1980),Milton Friedmanand his wifeRose Friedmanforetold: "Once the aged Marshal Tito dies, Yugoslavia will experience political instability that may produce a reaction toward greaterauthoritarianismor, far less likely, a collapse of existing collectivist arrangements ". (Tito died soon after the book was published.)

Death of Tito and the weakening of Communism

[edit]On 4 May 1980, Tito's death was announced through state broadcasts across Yugoslavia. His death removed what many international political observers saw as Yugoslavia's main unifying force, and subsequentlyethnic tensionstarted to grow in Yugoslavia. The crisis that emerged in Yugoslavia was connected with the weakening of theCommunist states in Eastern Europetowards the end of theCold War,leading to the fall of theBerlin Wallin 1989. In Yugoslavia, the national communist party, officially called theLeague of Communists of Yugoslavia,had lost its ideological base.[16]

In 1986, theSerbian Academy of Sciences and Arts(SANU) contributed significantly to the rise of nationalist sentiments, as it drafted the controversialSANU Memorandumprotesting against the weakening of the Serbian central government.

The problems in the SerbianSocialist Autonomous Province of Kosovobetweenethnic SerbsandAlbaniansgrew exponentially. This, coupled with economic problems in Kosovo and Serbia as a whole, led to even greater Serbian resentment of the1974 Constitution.Kosovo Albanians started to demand that Kosovo be granted the status of a constituent republic beginning in the early 1980s, particularly with the1981 protests in Kosovo.This was seen by the Serbian public as a devastating blow to Serb pride because of the historic links that Serbians held with Kosovo. It was viewed that that secession would be devastating to Kosovar Serbs. This eventually led to the repression of the Albanian majority in Kosovo.[17][not specific enough to verify]

Meanwhile, the more prosperous republics ofSR SloveniaandSR Croatiawanted to move towards decentralization and democracy.[18]

The historianBasil Davidsoncontends that the "recourse to 'ethnicity' as an explanation [of the conflict] is pseudo-scientific nonsense". Even the degree of linguistic and religious differences "have been less substantial than instant commentators routinely tell us".[citation needed]Davidson agrees withSusan Woodward,who found the "motivating causes of the disintegration in economic circumstance and its ferocious pressures".[19]Likewise, Sabine Rutar states that, “while antagonistic representations of the ethnic-national past indeed were heavily (mis-)used during the conflict, one must be careful not to turn these forceful categories of practice into categories of historical analysis”.[20]

Economic collapse and the international climate

[edit]As President, Tito's policy was to push for rapideconomic growth,and growth was indeed high in the 1970s. However, the over-expansion of the economy causedinflationand pushed Yugoslavia intoeconomic recession.[21]

A major problem for Yugoslavia was the heavy debt incurred in the 1970s, which proved to be difficult to repay in the 1980s.[22]Yugoslavia's debt load, initially estimated at a sum equal to $6 billion U.S. dollars, instead turned out to be equivalent to $21 billion U.S. dollars, which was a colossal sum for a poor country.[22]In 1984, theReagan administrationissued aclassifieddocument,National Security Decision Directive133, expressing concern that Yugoslavia's debt load might cause the country to align with the Soviet bloc.[23]The 1980s were a time ofeconomic austerityas theInternational Monetary Fund(IMF) imposed stringent conditions on Yugoslavia, which caused much resentment toward the Communist elites who had so mismanaged the economy by recklessly borrowing money abroad.[24][failed verification]The policies of austerity also led to uncovering much corruption on the part of the elites, most notably with the "Agrokomerc affair" of 1987, when theAgrokomercenterprise of Bosnia turned out to be the centre of a vast nexus of corruption running all across Yugoslavia, and that the managers of Agrokomerc had issued promissory notes equivalent to almost US$1 billion[25]without collateral, forcing the state to assume responsibility for their debts when Agrokomerc finally collapsed.[24][failed verification]The rampant corruption in Yugoslavia, of which the "Agrokomerc affair" was merely the most dramatic example, did much to discredit the Communist system, as it was revealed that the elites were living luxurious lifestyles, well beyond the means of ordinary people, with money stolen from the public purse during a time of austerity.[24][failed verification]The problems imposed by heavy indebtedness and corruption had by the mid-1980s increasingly started to corrode the legitimacy of the Communist system, as ordinary people started to lose faith in the competence and honesty of the elites.[24][failed verification]

A wave of major strikes developed in 1987–88 as workers demanded higher wages to compensate for inflation, as the IMF mandated the end of varioussubsidies,and they were accompanied by denunciations of the entire system as corrupt.[26][failed verification]Finally, the politics of austerity brought to the fore tensions between the well off "have" republics like Slovenia and Croatia versus the poorer "have not" republics like Serbia.[26][failed verification]Both Croatia and Slovenia felt that they were paying too much money into the federal budget to support the "have not" republics, while Serbia wanted Croatia and Slovenia to pay more money into the federal budget to support them at a time of austerity.[27][failed verification]Increasingly, demands were voiced in Serbia for more centralisation in order to force Croatia and Slovenia to pay more into the federal budget, demands that were completely rejected in the "have" republics.[28]

Therelaxation of tensionswith the Soviet Union afterMikhail GorbachevbecameGeneral Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union,the top position in 1985, meant that western nations were no longer willing to be generous with restructuring Yugoslavia's debts, as the example of a communist country outside of theEastern Blocwas no longer needed by the West as a way of destabilising the Soviet bloc. The external status quo, which the Communist Party had depended upon to remain viable, was thus beginning to disappear. Furthermore, the failure of communism all overCentral and Eastern Europeonce again brought to the surface Yugoslavia's inner contradictions,economic inefficiencies(such as chronic lack of productivity, fuelled by the country's leaderships' decision to enforce a policy offull employment), and ethno-religious tensions. Yugoslavia'snon-aligned statusresulted in access to loans from both superpower blocs. This contact with the United States and the West opened up Yugoslavia's markets sooner than the rest of Central and Eastern Europe. The 1980s were a decade of Western economic ministrations.[citation needed]

A decade of frugality resulted in growing frustration and resentment against both the Serbian "ruling class", and the minorities who were seen to benefit from government legislation. Real earnings in Yugoslavia fell by 25% from 1979 to 1985. By 1988, emigrant remittances to Yugoslavia totalled over $4.5 billion (USD), and by 1989 remittances were $6.2 billion (USD), making up over 19% of the world's total.[14][15]

In 1990, US policy insisted on theshock therapyausterity programme that was meted out to the ex-Comeconcountries. Such a programme had been advocated by the IMF and other organisations "as a condition for fresh injections of capital."[29]

Rise of nationalism in Serbia (1987–1989)

[edit]Slobodan Milošević

[edit]

In 1987, Serbian officialSlobodan Miloševićwas sent to bring calm to an ethnically driven protest by Serbs against the Albanian administration of SAP Kosovo. Milošević had been, up to this point, a hard-line communist who had decried all forms of nationalism as treachery, such as condemning theSANU Memorandumas "nothing else but the darkest nationalism".[30]However, Kosovo's autonomy had always been an unpopular policy in Serbia, and he took advantage of the situation and made a departure from traditional communist neutrality on the issue of Kosovo.

Milošević assured Serbs that their mistreatment by ethnic Albanians would be stopped. He then began a campaign against the ruling communist elite of SR Serbia, demanding reductions in the autonomy of Kosovo and Vojvodina. These actions made him popular amongst Serbs and aided his rise to power in Serbia. Milošević and his allies took on an aggressive nationalist agenda of reviving SR Serbia within Yugoslavia, promising reforms and protection of all Serbs.

The ruling party of SFR Yugoslavia was theLeague of Communists of Yugoslavia(SKJ), a composite political party made-up of eight Leagues of Communists from the six republics and two autonomous provinces. TheLeague of Communists of Serbia(SKS) governed SR Serbia. Riding the wave of nationalist sentiment and his new popularity gained in Kosovo, Slobodan Milošević (Chairman of the League of Communists of Serbia (SKS) since May 1986) became the most powerful politician in Serbia by defeating his former mentor President of SerbiaIvan Stambolicat the8th Session of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Serbiaon 23–24 September 1987. At a 1988 rally in Belgrade, Milošević made clear his perception of the situation facing SR Serbia in Yugoslavia, saying:

At home and abroad, Serbia's enemies are massing against us. We say to them "We are not afraid. We will not flinch from battle".

— Slobodan Milošević, 19 November 1988.[31]

On another occasion, he privately stated:

We Serbs will act in the interest of Serbia whether we do it in compliance with the constitution or not, whether we do it in compliance in the law or not, whether we do it in compliance with party statutes or not.

— Slobodan Milošević[32]

Anti-bureaucratic revolution

[edit]TheAnti-bureaucratic revolutionwas a series of protests in Serbia and Montenegro orchestrated by Milošević to put his supporters in SAP Vojvodina, SAP Kosovo, and theSocialist Republic of Montenegro(SR Montenegro) to power as he sought to oust his rivals. The government of Montenegro survived a coup d'état in October 1988,[33]but not a second one in January 1989.[34]

In addition to Serbia itself, Milošević could now install representatives of the two provinces and SR Montenegro in the Yugoslav Presidency Council. The very instrument that reduced Serbian influence before was now used to increase it: in the eight member Presidency, Milošević could count on a minimum of four votes – SR Montenegro (following local events), his own through SR Serbia, and now SAP Vojvodina and SAP Kosovo as well. In a series of rallies, called "Rallies of Truth", Milošević's supporters succeeded in overthrowing local governments and replacing them with his allies.

As a result of these events, in February 1989ethnic Albanianminers in Kosovoorganized a strike,demanding the preservation of the now-endangered autonomy.[35]This contributed to ethnic conflict between the Albanian and Serb populations of the province. At77% of the populationof Kosovo in the 1980s, ethnic-Albanians were the majority.

In June 1989, the 600th anniversary of Serbia'shistoric defeatat the field of Kosovo, Slobodan Milošević gave theGazimestan speechto 200,000 Serbs, with a Serb nationalist theme which deliberately evokedmedieval Serbian history.Milošević's answer to the incompetence of the federal system was to centralise the government. Considering Slovenia and Croatia were looking farther ahead to independence, this was considered unacceptable.

Repercussions

[edit]Meanwhile, theSocialist Republic of Croatia(SR Croatia) and theSocialist Republic of Slovenia(SR Slovenia), supported the Albanian miners and their struggle for recognition. Media in SR Slovenia published articles comparing Milošević toItalian fascistdictatorBenito Mussolini.Milošević contended that such criticism was unfounded and amounted to "spreading fear of Serbia".[36]Milošević's state-run media claimed in response thatMilan Kučan,head of theLeague of Communists of Slovenia,was endorsing Kosovo and Slovene separatism. Initial strikes in Kosovo turned into widespread demonstrations calling for Kosovo to be made the seventh republic. This angered Serbia's leadership which proceeded to use police force, and later the federal army (theYugoslav People's ArmyJNA) by order of the Serbian-controlled Presidency.

In February 1989 ethnic AlbanianAzem Vllasi,SAP Kosovo's representative on the Presidency, was forced to resign and was replaced by an ally of Milošević. Albanian protesters demanded that Vllasi be returned to office, and Vllasi's support for the demonstrations caused Milošević and his allies to respond stating this was a "counter-revolution against Serbia and Yugoslavia", and demanded that the federal Yugoslav government put down the striking Albanians by force. Milošević's aim was aided when a huge protest was formed outside of the Yugoslav parliament in Belgrade by Serb supporters of Milošević who demanded that the Yugoslav military forces make their presence stronger in Kosovo to protect the Serbs there and put down the strike.

On 27 February, SR Slovene representative in the collective presidency of Yugoslavia,Milan Kučan,opposed the demands of the Serbs and left Belgrade for SR Slovenia where he attended a meeting in theCankar Hallin Ljubljana, co-organized with thedemocratic opposition forces,publicly endorsing the efforts of Albanian protesters who demanded that Vllasi be released. In the 1995BBC2documentaryThe Death of Yugoslavia,Kučan claimed that in 1989, he was concerned that with the successes of Milošević's anti-bureaucratic revolution in Serbia's provinces as well as Montenegro, that his small republic would be the next target for apolitical coupby Milošević's supporters if the coup in Kosovo went unimpeded.Serbian state-run televisiondenounced Kučan as a separatist, a traitor, and an endorser of Albanian separatism.

Serb protests continued in Belgrade demanding action in Kosovo. Milošević instructed communist representativePetar Gračaninto make sure the protest continued while he discussed matters at the council of the League of Communists, as a means to induce the other members to realize that enormous support was on his side in putting down the Albanian strike in Kosovo. Serbian parliament speakerBorisav Jović,a strong ally of Milošević, met with the current President of the Yugoslav Presidency, Bosnian representativeRaif Dizdarević,and demanded that the federal government concede to Serbian demands. Dizdarević argued with Jović saying that "You [Serbian politicians] organized the demonstrations, you control it", Jović refused to take responsibility for the actions of the protesters. Dizdarević then decided to attempt to bring calm to the situation himself by talking with the protesters, by making an impassioned speech for unity of Yugoslavia saying:

Our fathers died to create Yugoslavia. We will not go down the road to national conflict. We will take the path ofBrotherhood and Unity.

— Raif Dizdarević, 1989.[31]

This statement received polite applause, but the protest continued. Later Jović spoke to the crowds with enthusiasm and told them that Milošević was going to arrive to support their protest. When Milošević arrived, he spoke to the protesters and jubilantly told them that the people of Serbia were winning their fight against the old party bureaucrats. A shout came from the crowd to "arrest Vllasi". Milošević pretended not to hear the demand correctly but declared to the crowd that anyone conspiring against the unity of Yugoslavia would be arrested and punished. The next day, with the party council pushed into submission to Serbia, Yugoslav army forces poured into Kosovo and Vllasi was arrested.

In March 1989, the crisis in Yugoslavia deepened after the adoption of amendments to theSerbian constitutionthat allowed the Serbian republic's government to re-assert effective power over the autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. Up until that time, a number of political decisions were legislated from within these provinces, and they had a vote on theYugoslav federal presidencylevel (six members from the republics and two members from the autonomous provinces).[37]

A group of Kosovo Serb supporters of Milošević who helped bring down Vllasi declared that they were going to Slovenia to hold "theRally of Truth"which would decry Milan Kučan as a traitor to Yugoslavia and demand his ousting. However, the attempt to replay the anti-bureaucratic revolution inLjubljanain December 1989 failed: the Serb protesters who were to go by train to Slovenia were stopped when the police of SR Croatia blocked all transit through its territory in coordination with the Slovene police forces.[38][39][40]

In thePresidency of Yugoslavia,Serbia'sBorisav Jović(at the time the President of the Presidency), Montenegro'sNenad Bućin,Vojvodina'sJugoslav Kostićand Kosovo'sRiza Sapunxhiu,started to form a voting bloc.[41]

Final political crisis (1990–1992)

[edit]Party crisis

[edit]In January 1990, the extraordinary14th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslaviawas convened. The combined Yugoslav ruling party, theLeague of Communists of Yugoslavia(SKJ), was in crisis. Most of the Congress was spent with the Serbian and Slovene delegations arguing over the future of the League of Communists and Yugoslavia. SR Croatia prevented Serb protesters from reaching Slovenia. The Serbian delegation, led by Milošević, insisted on a policy of "one person, one vote" in the party membership, which would empower the largest party ethnic group, theSerbs.

In turn, the Croats and Slovenes sought to reform Yugoslavia by delegating even more power to six republics, but were voted down continuously in every motion and attempt to force the party to adopt the new voting system. As a result, the Croatian delegation, led by ChairmanIvica Račan,and Slovene delegation left the Congress on 23 January 1990, effectively dissolving the all-Yugoslav party. Along with external pressure, this caused the adoption of multi-party systems in all the republics.

Multi-party elections

[edit]The individual republics organized multi-party elections in 1990, and the former communists mostly failed to win re-election, while most of the elected governments took on nationalist platforms, promising to protect their separate nationalist interests. In multi-party parliamentary elections nationalists defeated re-branded former Communist parties in Slovenia on8 April 1990,in Croatia on22 April and 2 May 1990,in Macedonia11 and 25 November and 9 December 1990,and in Bosnia and Herzegovina on18 and 25 November 1990.

In multi-party parliamentary elections, re-branded former communist parties were victorious in Montenegro on9 and 16 December 1990,and in Serbia on9 and 23 December 1990.In addition Serbia re-elected Slobodan Milošević as president. Serbia and Montenegro now increasingly favored a Serb-dominated Yugoslavia.

Ethnic tensions in Croatia

[edit]In Croatia, thenationalistCroatian Democratic Union(HDZ) was elected to power, led by controversial nationalistFranjo Tuđman,under the promise of "protecting Croatia from Milošević", publicly advocating Croatian sovereignty.Croatian Serbswere wary of Tuđman's nationalist government, and in 1990Serb nationalistsin the southern Croatian town ofKninorganized and formed a separatist entity known as theSAO Krajina,which demanded to remain in union with the rest of the Serb population if Croatia decided to secede. The government of Serbia endorsed the rebellion of theCroatian Serbs,claiming that for Serbs, rule under Tuđman's government would be equivalent to theWorld War IIerafascistIndependent State of Croatia(NDH), which committedgenocide against Serbs.Milošević used this to rally Serbs against the Croatian government and Serbian newspapers joined in the warmongering.[43]Serbia had by now printed $1.8 billion worth of new money without any backing of theYugoslav National Bank.[44]

Croatian Serbs inKnin,under the leadership of local police inspectorMilan Martić,began to try to gain access to weapons so that the Croatian Serbs could mount a successful revolt against the Croatian government. Croatian Serb politicians including the Mayor of Knin met withBorisav Jović,the head of the Yugoslav Presidency in August 1990, and urged him to push the council to take action to prevent Croatia from separating from Yugoslavia, because they claimed that the Serb population would be in danger in Croatia which was ruled by Tuđman and his nationalist government.

At the meeting, army officialPetar Gračanintold the Croatian Serb politicians how to organize their rebellion, telling them to put up barricades, as well as assemble weapons of any sort, saying "If you can't get anything else, use hunting rifles". Initially the revolt became known as the "Log Revolution",as Serbs blockaded roadways to Knin with cut-down trees and prevented Croats from entering Knin or the Croatian coastal region ofDalmatia.The BBC documentaryThe Death of Yugoslaviarevealed that at the time, Croatian TV dismissed the "Log Revolution" as the work of drunken Serbs, trying to diminish the serious dispute. However, the blockade was damaging to Croatian tourism. The Croatian government refused to negotiate with the Serb separatists and decided to stop the rebellion by force, sending in armed special forces by helicopters to put down the rebellion.

The pilots claimed they were bringing "equipment" to Knin, but the federalYugoslav Air Forceintervened and sentfighter jetsto intercept them and demanded that thehelicoptersreturn to their base or they would be fired upon, in which the Croatian forces obliged and returned to their base inZagreb.To the Croatian government, this action by the Yugoslav air force revealed to them that theYugoslav People's Armywas increasingly under Serbian control. SAO Krajina was officially declared a separate entity on 21 December 1990 by theSerbian National Councilwhich was headed byMilan Babić.

In August 1990 theCroatian Parliamentreplaced its representativeStipe ŠuvarwithStjepan Mesićin the wake of the Log Revolution.[45]Mesić was only seated in October 1990 because of protests from the Serbian side, and then joined Macedonia'sVasil Tupurkovski,Slovenia'sJanez Drnovšekand Bosnia and Herzegovina'sBogić Bogićevićin opposing the demands to proclaim a generalstate of emergency,which would have allowed theYugoslav People's Armyto imposemartial law.[41]

Following the first multi-party election results, the republics of Slovenia, Croatia, and Macedonia proposed transforming Yugoslavia into a loose federation of six republics in the autumn of 1990, however Milošević rejected all such proposals, arguing that like Slovenes and Croats, the Serbs also had a right to self-determination. Serbian politicians were alarmed by a change of phrasing in theChristmas Constitutionof Croatia that changed the status of ethnic Serbs of Croatia from an explicitly mentioned nation (narod) to a nation listed together with minorities (narodi i manjine).[clarification needed]

Independence of Slovenia and Croatia

[edit]

In the1990 Slovenian independence referendum,held on 23 December 1990, a vast majority of residents voted for independence:[48]88.5% of all electors (94.8% of those participating) voted for independence, which was declared on 25 June 1991.[49][50]

In January 1991, the Yugoslav counter-intelligence service,KOS(Kontraobaveštajna služba), displayed a video of a secret meeting (the "Špegelj Tapes") that they purported had happened some time in 1990 between the Croatian Defence Minister,Martin Špegelj,and two other men.[citation needed]Špegelj announced during the meeting that Croatia was at war with theYugoslav People's Army(JNA,Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija) and gave instructions about arms smuggling as well as methods of dealing with the Army's officers stationed in Croatian cities. The Army subsequently wanted to indict Špegelj for treason and illegal importation of arms, mainly fromHungary.[citation needed]

The discovery of Croatian arms smuggling combined with the crisis in Knin, the election of independence-leaning governments in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, and Slovenia, and Slovenes demanding independence in the referendum on the issue suggested that Yugoslavia faced the imminent threat of disintegration.

On 1 March 1991, thePakrac clashensued, and the JNA was deployed to the scene. On 9 March 1991,protests in Belgradewere suppressed with the help of the Army.

On 12 March 1991, the leadership of the Army met with thePresidencyin an attempt to convince them to declare astate of emergencywhich would allow for the pan-Yugoslav army to take control of the country. Yugoslav army chiefVeljko Kadijevićdeclared that there was a conspiracy to destroy the country, saying:

An insidious plan has been drawn up to destroy Yugoslavia. Stage one is civil war. Stage two is foreign intervention. Then puppet regimes will be set up throughout Yugoslavia.

— Veljko Kadijević, 12 March 1991.[31]

This statement effectively implied that the new independence-advocating governments of the republics were seen by Serbs as tools of the West. Croatian delegateStjepan Mesićresponded angrily to the proposal, accusing Jović and Kadijević of attempting to use the army to create aGreater Serbiaand declared "That means war!". Jović and Kadijević then called upon the delegates of each republic to vote on whether to allow martial law, and warned them that Yugoslavia would likely fall apart if martial law was not introduced.

In the meeting, a vote was taken on a proposal to enactmartial lawto allow for military action to end the crisis in Croatia by providing protection for the Serbs. The proposal was rejected as the Bosnian delegateBogić Bogićevićvoted against it, believing that there was still the possibility of diplomacy being able to solve the crisis.

The Yugoslav presidential crisis reached an impasse when Kosovo'sRiza Sapunxhiu'defected' his faction in the second vote on martial law in March 1991.[41] Jović briefly resigned from the presidency in protest, but soon returned.[41]On 16 May 1991, the Serbian parliament replaced Sapunxhiu withSejdo Bajramović,and Vojvodina'sNenad BućinwithJugoslav Kostić.[51]This effectively deadlocked the Presidency, because Milošević's Serbian faction had secured four out of eight federal presidency votes, and it was able to block any unfavorable decisions at the federal level, in turn causing objections from other republics and calls for reform of the Yugoslav Federation.[41][52][53]

After Jović's term as head of the collective presidency expired, he blocked his successor, Mesić, from taking the position, giving the position instead toBranko Kostić,a member of the pro-Milošević government in Montenegro.

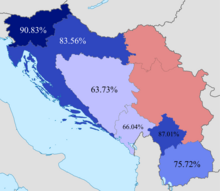

In theCroatian independence referendum held on 2 May 1991,93.24% voted for independence. On 19 May 1991, the second round of the referendum on the structure of the Yugoslav federation was held in Croatia. The phrasing of the question did not explicitly inquire as to whether one was in favor of secession or not. Voters were asked if they supported Croatia being "able to enter into an alliance of sovereign states with other republics (in accordance with the proposal of the republics of Croatia and Slovenia for solving the state crisis in the SFRY)?". 83.56% of the voters turned out, with Croatian Serbs largely boycotting the referendum. Of these, 94.17% (78.69% of the total voting population) voted "in favor" of the proposal, while 1.2% of those who voted were "opposed". Finally, theindependence of Croatiawas declared on 25 June 1991.

The beginning of the Yugoslav Wars

[edit]War in Slovenia (1991)

[edit]Both Slovenia and Croatia declared their independence on 25 June 1991. This was declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court of Yugoslavia, as the1974 Yugoslav Constitutionrequired unanimity of all republics for the secession of any of the republics (Articles 5, 203, 237, 240, 244 and 281).

On the morning of 26 June, units of the Yugoslav People's Army's 13th Corps left their barracks inRijeka,Croatia,to move towardsSlovenia's borders withItaly.The move immediately led to a strong reaction from local Slovenians, who organized spontaneousbarricadesand demonstrations against the YPA's actions. There was no fighting, as yet, and both sides appeared to have an unofficial policy of not being the first to open fire.

By this time, the Slovenian government had already put into action its plan to seize control of both the internationalLjubljana Airportand Slovenia's border posts on borders with Italy, Austria and Hungary. The personnel manning the border posts were, in most cases, already Slovenians, so the Slovenian take-over mostly simply amounted to changing of uniforms and insignia, without any fighting. By taking control of the borders, the Slovenians were able to establish defensive positions against an expected YPA attack. This meant that the YPA would have to fire the first shot, which was fired on 27 June at 14:30 inDivačaby an officer of the YPA.[54]

Whilst supportive of their respective rights to national self-determination, theEuropean CommunitypressuredSloveniaandCroatiato place a three-month moratorium on their independence, and reached theBrioni Agreementon 7 July 1991 (recognized by representatives of all republics).[55]During these three months, the Yugoslav Army completed its pull-out from Slovenia. Negotiations to restore the Yugoslav federation with diplomatLord Carringtonand members of theEuropean Communitywere all but ended. Carrington's plan realized that Yugoslavia was in a state of dissolution and decided that each republic must accept the inevitable independence of the others, along with a promise to Serbian President Milošević that theEuropean Communitywould ensure thatSerbs outside of Serbiawould be protected.

Milošević refused to agree to the plan, as he claimed that the European Community had no right to dissolve Yugoslavia and that the plan was not in the interests of Serbs as it would divide the Serb people into four republics (Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia). Carrington responded by putting the issue to a vote in which all the other republics, including Montenegro underMomir Bulatović,initially agreed to the plan that would dissolve Yugoslavia. However, after intense pressure from Serbia on Montenegro's president, Montenegro changed its position to oppose the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

Lord Carrington's opinions were rendered moot followingnewly reunitedGermany's Christmas Eve 1991 recognition of Slovenia and Croatia. Except for secret negotiations between foreign ministersHans-Dietrich Genscher(Germany) andAlois Mock(Austria), the unilateral recognition came as an unwelcome surprise to most EC governments and theUnited States,with whom there was no prior consultation. International organisations, including theUnited Nations,were nonplussed. While Yugoslavia was already in a shambles, it is likely that German recognition of the breakaway republics—and Austrian partial mobilization on the border—made things a good deal worse for the decomposing multinational state. US PresidentGeorge H.W. Bushwas the only major power representative to voice an objection. The extent ofVaticanand Federal Intelligence Agency of Germany (BND) intervention in this episode has been explored by scholars familiar with the details, but the historical record remains disputed.

War in Croatia (1991)

[edit] |

|---|

With thePlitvice Lakes incidentof late March/early April 1991, theCroatian War of Independencebroke out between the Croatian government and the rebel ethnic Serbs of theSerbian Autonomous Province of Krajina(heavily backed by the by-now Serb-controlled Yugoslav People's Army). On 1 April 1991, theSAO Krajinadeclared that it would secede from Croatia. Immediately after Croatia's declaration of independence, Croatian Serbs also formed theSAO Western Slavoniaand theSAO of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Srijem.These three regions would combine into the self-proclaimedproto-stateRepublic of Serbian Krajina(RSK) on 19 December 1991.

The other significant Serb-dominated entities ineastern Croatiaannounced that they too would join SAO Krajina. Zagreb had by this time discontinued submitting tax money to Belgrade, and the Croatian Serb entities in turn halted paying taxes to Zagreb. In some places, the Yugoslav Army acted as abuffer zone,[where?]in others it aided Serbs in their confrontation with the newCroatian armyand police forces.[clarification needed]

The influence ofxenophobiaand ethnic hatred in the collapse of Yugoslavia became clear during the war in Croatia. Propaganda by Croatian and Serbian sides spread fear, claiming that the other side would engage in oppression against them and would exaggerate death tolls to increase support from their populations.[56]In the beginning months of the war, the Serb-dominated Yugoslav army and navy deliberately shelled civilian areas ofSplitandDubrovnik,aUNESCO World Heritage Site,as well as nearby Croat villages.[57]Yugoslav media claimed that the actions were done due to what they claimed was a presence of fascist Ustaše forces and international terrorists in the city.[57]

UN investigations found that no such forces were in Dubrovnik at the time.[57]Croatian Armed Forcespresence increased later on. Montenegrin Prime MinisterMilo Đukanović,at the time an ally of Milošević, appealed toMontenegrin nationalism,promising that the capture of Dubrovnik would allow the expansion of Montenegro into the city which he claimed was historically part of Montenegro, and denounced the present borders of Montenegro as being "drawn by the old and poorly educatedBolshevikcartographers ".[57]

At the same time, the Serbian government contradicted its Montenegrin allies with claims by the Serbian Prime MinisterDragutin Zelenovićthat Dubrovnik was historically Serbian, not Montenegrin.[58]The international media gave immense attention tobombardment of Dubrovnikand claimed this was evidence of Milosevic pursuing the creation of aGreater Serbiaas Yugoslavia collapsed, presumably with the aid of the subordinate Montenegrin leadership of Bulatović and Serb nationalists in Montenegro to foster Montenegrin support for the retaking of Dubrovnik.[57]

InVukovar,ethnic tensions between Croats and Serbs exploded into violence when theYugoslav army entered the town.The Yugoslav army andSerbian paramilitariesdevastated the town inurban warfareand the destruction of Croatian property. Serb paramilitaries committed atrocities against Croats, killing over 200, and displacing others to add to those who fled the town in theVukovar massacre.[59]

Independence of the Republic of Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]

With Bosnia's demographic structure comprising a mixed population of a plurality ofBosniaks,and minorities of Serbs and Croats, the ownership of large areas of Bosnia was in dispute.

From 1991 to 1992, the situation in the multiethnic Bosnia and Herzegovina grew tense. Its parliament was fragmented on ethnic lines into a plurality Bosniak faction and minority Serb and Croat factions. In October 1991,Radovan Karadžić,the leader of the largest Serb faction in the parliament, theSerb Democratic Party,gave a grave and direct warning to thePeople's Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovinashould it decide to separate, saying:

This, what you are doing, is not good. This is the path that you want to take Bosnia and Herzegovina on, the same highway of hell and death that Slovenia and Croatia went on. Don't think that you won't take Bosnia and Herzegovina into hell, and the Muslim people maybe into extinction. Because the Muslim people cannot defend themselves if there is war here.

— Radovan Karadžić, 14 October 1991.[60]

In the meantime, behind the scenes, negotiations began between Milošević and Tuđman to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina into Serb and Croat administered territories to attempt to avert war betweenBosnian CroatsandBosnian Serbs.[61]Bosnian Serbs held areferendum in November 1991resulting in an overwhelming vote in favor of staying in a common state with Serbia and Montenegro.

In public, pro-state media inSerbiaclaimed to Bosnians that Bosnia and Herzegovina could be included a new voluntary union within a new Yugoslavia based on democratic government, but this was not taken seriously by Bosnia and Herzegovina's government.[62]

On 9 January 1992, the Bosnian Serb assembly proclaimed a separate Republic of the Serb people of Bosnia and Herzegovina (the soon-to-beRepublika Srpska), and proceeded to formSerbian autonomous regions(SARs) throughout the state. The Serbian referendum on remaining in Yugoslavia and the creation of SARs were proclaimed unconstitutional by the government of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Areferendum on independencesponsored by the Bosnian government was held on 29 February and 1 March 1992. The referendum was declared contrary to the Bosnian and federal constitution by the federal Constitution Court and the newly established Bosnian Serb government, and it was largely boycotted by the Bosnian Serbs. According to the official results, the turnout was 63.4%, and 99.7% of the voters voted for independence.[63]It was unclear what the two-thirds majority requirement actually meant and whether it was satisfied.

Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on 3 March 1992 and received international recognition the following month on 6 April 1992.[64]On the same date, the Serbs responded by declaring the independence of theRepublika Srpskaandlaying siege to Sarajevo,which marked the start of theBosnian War.[65]TheRepublic of Bosnia and Herzegovinawas subsequently admitted as a member state of the United Nations on 22 May 1992.[66]

InBosnia and Herzegovina,NATO airstrikes against Bosnian Serb targetscontributed to the signing of the 14 December 1995Dayton Agreementand the resolution of the conflict. Around 100,000 people were killed over the course of the war.[67]

Macedonia

[edit]In theMacedonian independence referendumheld on 8 September 1991, 95.26% voted for independence, which was declared on 25 September 1991.[68]

Five hundred US soldiers were then deployed under the UN banner to monitor Macedonia's northern border with Serbia. However, Belgrade's authorities neither intervened to prevent Macedonia's departure, nor protested nor acted against the arrival of the UN troops, indicating that once Belgrade was to form its new country (theFederal Republic of Yugoslaviain April 1992), it would recognise the Republic of Macedonia and develop diplomatic relations with it. As a result, Macedonia became the only former republic to gain sovereignty without resistance from the Yugoslav authorities and Army.

In addition, Macedonia's first president,Kiro Gligorov,did indeed maintain good relations with Belgrade as well as the other former republics. There have been no problems between Macedonian and Serbian border police, even though small pockets of Kosovo and thePreševovalley complete the northern reaches of the historical region known as Macedonia, which would otherwise have created a border dispute (see alsoIMORO).

Theinsurgency in the Republic of Macedonia,the last major conflict being betweenAlbanian nationalistsand the government of Republic of Macedonia, reduced in violence after 2001.

International recognition of the breakup

[edit]

While France, Britain and most otherEuropean Communitymember nations were still emphasizing the need to preserve the unity of Yugoslavia,[69]the German chancellorHelmut Kohlled the charge to recognize the first two breakaway republics of Slovenia and Croatia. He lobbied both national governments and the EC to be more favourable to his policies, and also went to Belgrade to pressure the federal government not to use military action, threatening sanctions. Days before the end of the year on Christmas Eve, Germany recognized the independence of Slovenia and Croatia, "against the advice of the European Community, the UN, and US President George H W Bush".[70]

In November 1991, theArbitration Commission of the Peace Conference on Yugoslavia,led byRobert Badinter,concluded at the request ofLord Carringtonthat the SFR Yugoslavia was in the process of dissolution, that the Serbian population in Croatia and Bosnia did not have a right to self-determination in the form of new states, and that the borders between the republics were to be recognized as international borders. As a result of the conflict, theUnited Nations Security Councilunanimously adoptedUN Security Council Resolution 721on 27 November 1991, which paved the way to the establishment ofpeacekeepingoperations in Yugoslavia.[71]

In January 1992, Croatia and Yugoslaviasigned an armistice under UN supervision,while negotiations continued between Serb and Croat leaderships over thepartitioning of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[72]

On 15 January 1992, the independence of Croatia and Slovenia was recognized by the international community. Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina would later be admitted asmember states of the United Nationson 22 May 1992. Macedonia was admitted as a member state of the United Nations on 8 April 1993;[73]its membership approval took longer than the others due to Greek objections.[73]

In 1999Social Democratic Party of GermanyleaderOskar Lafontainecriticised the role played by Germany in the break up of Yugoslavia, with its early recognition of the independence of the republics, during his May Day speech.[74]

Some observers opined that the break up of the Yugoslav state violated the principles ofpost-Cold War system,enshrined in theOrganization for Security and Co-operation in Europe(CSCE/OSCE) and theTreaty of Parisof 1990. Both stipulated that inter-state borders in Europe should not be changed. Some observers, such as Peter Gowan, assert that the breakup and subsequent conflict could have been prevented if western states were more assertive in enforcing internal arrangements between all parties, but ultimately "were not prepared to enforce such principles in the Yugoslav case because Germany did not want to, and the other states did not have any strategic interest in doing so."[75]Gowan even contends that the break-up "might have been possible without great bloodshed if clear criteria could have been established for providing security for all the main groups of people within the Yugoslav space."

In March 1992, during the US-Bosnian independence campaign, the politician and future president of Bosnia and HerzegovinaAlija Izetbegovićreached an EC brokered agreement with Bosnian Croats and Serbs on a three-canton confederal settlement. But, the US government, according toThe New York Times,urged him to opt for a unitary, sovereign, independent state.[76]

Aftermath in Serbia and Montenegro

[edit]

The independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina proved to be the final blow to the pan-Yugoslav Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. On 28 April 1992, the Serb-dominatedFederal Republic of Yugoslavia(FRY) wasformedas arump state,consisting only of the former Socialist Republics of Montenegro and Serbia. The FRY was dominated by Slobodan Milošević and his political allies. Its government claimed continuity to the former country, but the international community refused to recognize it as such. The stance of the international community was that Yugoslavia had dissolved into its separate states. The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was prevented by a UN resolution on 22 September 1992 from continuing to occupy the United Nations seat assuccessor state to SFRY.

The disintegration and war led to asanctions regime,causing theeconomy of Serbia and Montenegroto collapse after five years. The war in the western parts of former Yugoslavia ended in 1995 with US-sponsored peace talks inDayton, Ohio,which resulted in theDayton Agreement.TheKosovo Warstarted in 1998 and ended with the1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia;Slobodan Milošević wasoverthrownon 5 October 2000.

The question of succession was important for claims on SFRY's international assets, including embassies in many countries. The FRY did not abandon its claim to continuity from the SFRY until 1996.[citation needed]After the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia re-applied formembership in the United Nationsand was admitted on 1 November 2000 as a new member.[77]TheAgreement on Succession Issues of the Former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslaviawas then signed on 29 June 2001, leading to the sharing of international assets among the five sovereign equal successor states.

The FR Yugoslavia was reconstructed on 4 February 2003 as theState Union of Serbia and Montenegro.The State Union of Serbia and Montenegro was itself unstable, and finally broke up in 2006 when, in areferendumheld on 21 May 2006, Montenegrin independence was backed by 55.5% of voters, and independence was declared on 3 June 2006. Serbia inherited the State Union's UN membership.[78]

Kosovohas been underinternational administrationsince 1999.

See also

[edit]- Role of the media in the breakup of Yugoslavia

- Dissolution of Czechoslovakia

- Dissolution of the Soviet Union

- Timeline of the breakup of Yugoslavia

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^Caesar, Faisal (23 June 2020)."The forgotten Yugoslavian side of Italia 90".Criketsoccer.

- ^"Decades later, Bosnia still struggling with the aftermath of war".PBS NewsHour.19 November 2017.

- ^"The Hungaro-Croatian Compromise of 1868 (The Nagodba)".h-net.org.Archived fromthe originalon 4 June 2011.

- ^Kishore, Dr Raghwendra (11 September 2021).International Relations.K.K. Publications.

- ^"Elections".Time.23 February 1925. Archived fromthe originalon 12 January 2008.

- ^Appeal to the international league of human rights,Albert Einstein/Heinrich Mann.

- ^Staff.Jasenovac concentration campArchived16 September 2009 at theWayback Machine,Jasenovac,Croatia, Yugoslavia. On the website of theUnited States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ^Cohen 1996,p. 109.

- ^Žerjavić 1993.

- ^World Bank, World Development Report 1991, Statistical Annex, Tables 1 and 2, 1991.

- ^Survey, Small Arms (5 July 2015).Small arms survey 2015: weapons and the world.[Cambridge, England].ISBN9781107323636.OCLC913568550.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^abcJović 2009,p. 15

- ^Jović,pp. 15–16

- ^abBeth J. Asch, Courtland Reichmann, Rand Corporation.Emigration and Its Effects on the Sending Country.Rand Corporation, 1994. p. 26.

- ^abDouglas S. Massey, J. Edward Taylor.International Migration: Prospects and Policies in a Global Market.Oxford University Press, 2004. p. 159.

- ^Pešić, Vesna(April 1996)."Serbian Nationalism and the Origins of the Yugoslav Crisis".Peaceworks(8).United States Institute of Peace:12.Retrieved10 December2010.

- ^"Kosovo".The New York Times.23 July 2010.Retrieved10 December2010.

- ^Kamm, Henry(8 December 1985)."Yugoslav republic jealously guards its gains".The New York Times.Retrieved10 December2010.

- ^Davidson, Basil (23 May 1996)."Misunderstanding Yugoslavia".London Review of Books.18(10).

- ^Rutar, Sabine (2013). "Nationalism in Southeastern Europe, 1970-2000". In Breuilly, John (ed.).The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism.Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 526.ISBN978-0-19-876820-3.

- ^"YUGOSLAVIA: KEY QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ON THE DEBT CRISIS"(PDF).Directorate of Intelligence.12 May 2011. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 24 January 2017.

- ^abM. Cvikl, Milan (June 1996)."Former Yugoslavia's Debt Apportionment"(PDF).documents1.worldbank.org.

- ^National Security Decision Directive 133,United States Policy Toward Yugoslavia,14 March 1984

- ^abcdCrampton 1997,p. 386–387.

- ^Tagliabue, John (5 January 1989)."Agrokomerc Ex-Director Goes on Hunger Strike in Jail".Associated Press.Retrieved10 September2021.

- ^abCrampton 1997,p. 387.

- ^Crampton 1997,p. 387-388.

- ^MacDonald, David Bruce (2002). "Tito's Yugoslavia and after".Balkan holocausts? Serbian and Croatian victim-centred propaganda and the war in Yugoslavia.New approaches to conflict analysis. Manchester; New York: New York: Manchester University Press. pp. 183–219.ISBN978-0-7190-6466-1.JSTORj.ctt155jbrm.12.

- ^Tagliabue, John (6 December 1987)."Austerity and Unrest on Rise in Eastern Block".The New York Times.Retrieved22 February2019.

- ^Lampe, John R. 2000.Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p347

- ^abcThe Death of Yugoslavia. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 1995.

- ^Ramet, Sabrina P. 2006. The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimisation. Indiana University Press. p598.

- ^Kamm, Henry(9 October 1988)."Yugoslav Police Fight Off A Siege in Provincial City".The New York Times.Retrieved2 February2010.

- ^"Leaders of a Republic in Yugoslavia Resign".The New York Times.Reuters.12 January 1989.Archivedfrom the original on 6 November 2012.Retrieved7 February2010.

- ^Ramet, Sabrina P. (18 February 2010).Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989.Cambridge University Press. p. 361.ISBN9780521716161.Retrieved9 March2012.

- ^"Communism O Nationalism!".Time.(24 October 1988).

- ^"A Country Study: Yugoslavia (Former): Political Innovation and the 1974 Constitution (chapter 4)".The Library of Congress.Retrieved27 January2011.

- ^"Historical Circumstances in Which" The Rally of Truth "in Ljubljana Was Prevented".Journal of Criminal Justice and Security. Archived fromthe originalon 13 December 2013.Retrieved4 July2012.

- ^"Rally of truth (Miting resnice)".A documentary published byRTV Slovenija.Retrieved4 July2012.

- ^"akcijasever.si".The "North" Veteran Organization. Archived fromthe originalon 29 December 2017.Retrieved3 July2012.

- ^abcde"Stjepan Mesić, svjedok kraja (I) – Ja sam inicirao sastanak na kojem je podijeljena Bosna".BH Dani(in Bosnian). No. 208. 1 June 2001. Archived fromthe originalon 24 November 2012.Retrieved27 November2012.

- ^"Stanovništvo prema nacionalnoj pripadnosti i površina naselja, popis 1991. za Hrvatsku"(PDF).p. 1. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 18 July 2020.

- ^"Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts".The New York Times.19 August 1990.Retrieved26 April2010.

- ^Sudetic, Chuck (10 January 1991)."Financial Scandal Rocks Yugoslavia".The New York Times.Retrieved26 April2010.

- ^Perišin, Tena (27 February 2008)."Svjedoci raspada – Stipe Šuvar: Moji obračuni s njima".Radio Slobodna Evropa(in Croatian).Radio Free Europe.Retrieved27 November2012.

- ^"1991 Rezultati Referendum"(PDF).izbori.hr.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 February 2012.Retrieved25 May2022.

- ^"CSCE:: Article:: Report: The Referendum on Independence in Bosnia-Herzegovina".csce.gov.Archived fromthe originalon 22 May 2011.Retrieved25 May2022.

- ^"REFERENDUM BRIEFING NO 3"(PDF).Archived fromthe originalon 18 December 2010.

- ^Flores Juberías, Carlos (November 2005)."Some legal (and political) considerations about the legal framework for referendum in Montenegro, in the light of European experiences and standards"(PDF).Legal Aspects for Referendum in Montenegro in the Context of International Law and Practice.Foundation Open Society Institute, Representative Office Montenegro. p. 74. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 1 February 2012.

- ^"Volitve"[Elections].Statistični letopis 2011[Statistical Yearbook 2011]. Vol. 15. Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. 2011. p. 108.ISSN1318-5403.

- ^Mesić (2004),p. 33

- ^Brown & Karim (1995),p. 116

- ^Frucht (2005),p. 433

- ^"Zgodilo se je... 27. junija"[It Happened On... 27 June] (in Slovenian). MMC RTV Slovenia. 27 June 2005.

- ^Woodward, Susan, L. Balkan Tragedy: Chaos & Dissolution after the Cold War, the Brookings Institution Press, Virginia, USA, 1995, p. 200

- ^"THE PROSECUTOR OF THE TRIBUNAL AGAINST SLOBODAN MILOSEVIC".Retrieved24 January2016.

- ^abcde"Pavlovic: The Siege of Dubrovnik".yorku.ca.

- ^"Pavlovic: The Siege of Dubrovnik".yorku.ca.

- ^"Two jailed over Croatia massacre".BBC News. 27 September 2007.Retrieved26 April2010.

- ^Karadzic and Mladic: The Worlds Most Wanted Men – FOCUS Information AgencyArchived16 April 2009 at theWayback Machine

- ^Lukic & Lynch 1996,p. 209.

- ^Burg, Steven L; Shoup, Paul S. 1999.The War in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention.M.E. Sharpe. p102

- ^The Referendum on Independence in Bosnia-Herzegovina: February 29-March 1, 1992.Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE)(Report). Washington D.C. 12 March 1992. Archived fromthe originalon 22 May 2011.

- ^Bose, Sumantra (2009).Contested lands: Israel-Palestine, Kashmir, Bosnia, Cyprus, and Sri Lanka.Harvard University Press. p. 124.ISBN9780674028562.

- ^Walsh, Martha (2001). Kumar, Krishna (ed.).Women and civil war: impact, organizations, and action.Boulder: L. Rienner Publishers. p. 57.ISBN978-1-55587-953-2.

The Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was recognized by the European Union on 6 April. On the same date, Bosnian Serb nationalists began the siege of Sarajevo, and the Bosnian war began

- ^D. Grant, Thomas (2009).Admission to the United Nations: Charter Article 4 and the Rise of Universal Organization.Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 226.ISBN978-9004173637.

- ^Logos 2019,p. 265, 412.

- ^Kasapović, Mirjana (2010),"Macedonia",Elections in Europe,Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, pp. 1271–1294,doi:10.5771/9783845223414-1271,ISBN978-3-8329-5609-7,retrieved26 October2020

- ^Drozdiak, William (2 July 1991)."Germany Criticizes European Community Policy on Yugoslavia".The Washington Post.ISSN0190-8286.Retrieved5 March2022.

- ^"Kohl's roll of the dice in 1991 helped further destabilise the Balkans".Financial Times.20 June 2017. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022.Retrieved5 March2022.

{{cite news}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^"Resolution 721".Belgium: NATO. 25 September 1991.Retrieved21 July2006.

- ^Lukic & Lynch 1996,p. 210.

- ^abRossos, Andrew(2008).Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History(PDF).Hoover Institution Press. p. 271.ISBN978-0817948832.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 28 January 2019.Retrieved28 January2019.

- ^Ali, Tariq (2000).Masters of the Universe? NATO's Balkan Crusade.Verso. p. 381.ISBN9781859842690.

- ^Gowan, Peter (March–April 1999)."The NATO Powers and the Balkan Tragedy".New Left Review(I/234): 83–105.

- ^"Leaders propose dividing Bosnia into three areas".The New York Times.17 June 1993.Retrieved2 March2019.

- ^"A Different Yugoslavia, 8 Years Later, Takes Its Seat at the U.N."The New York Times.2 November 2000.

- ^"Member States of the United Nations".United Nations.Retrieved19 November2012.

Sources

[edit]- Books

- Brown, Cynthia; Karim, Farhad (1995).Playing the "Communal Card": Communal Violence and Human Rights.New York City:Human Rights Watch.ISBN978-1-56432-152-7.

- Cohen, Philip J. (1996).Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History.Texas A&M University Press.ISBN0-89096-760-1.

- Crampton, R.J. (1997).A Concise History of Bulgaria.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521567190.

- Denitch, Bogdan Denis (1996).Ethnic nationalism: The tragic death of Yugoslavia.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.ISBN9780816629473.

- Djokić, Dejan (2003).Yugoslavism: Histories of a Failed Idea, 1918-1992.C. Hurst & Co. Publishers.ISBN978-1-85065-663-0.

- Frucht, Richard C. (2005).Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture.ABC-CLIO.ISBN978-1-57607-800-6.

- Ingrao, Charles; Emmert, Thomas A., eds. (2003).Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative(2nd ed.). Purdue University Press.ISBN978-1-55753-617-4.

- Jović, Dejan (2009).Yugoslavia: A State that Withered Away.Purdue University Press.ISBN978-1-55753-495-8.

- Logos, Aleksandar (2019).Istorija Srba 1, Dopuna 4; Istorija Srba 5.Beograd.ISBN978-86-85117-46-6.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lukic, Reneo; Lynch, Allen (1996).Europe from the Balkans to the Urals: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-829200-7.

- Mesić, Stjepan(2004).The Demise of Yugoslavia: A Political Memoir.Central European University Press.ISBN978-963-9241-81-7.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006).The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005.Indiana University Press.ISBN0-253-34656-8.

- Rogel, Carole (2004).The Breakup of Yugoslavia and Its Aftermath.Greenwood Publishing Group.ISBN0-313-32357-7.Retrieved22 April2012.

- Trbovich, Ana S. (2008).A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-533343-5.

- Wachtel, Andrew (1998).Making a Nation, Breaking a Nation: Literature and Cultural Politics in Yugoslavia.Stanford University Press.ISBN978-0-8047-3181-2.

- Žerjavić, Vladimir (1993).Yugoslavia: Manipulations with the Number of Second World War Victims.Croatian Information Centre.ISBN0-919817-32-7.Archived fromthe originalon 3 March 2016.Retrieved1 September2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Allcock, John B.; Milivojević, Marko; Horton, John J. (1998).Conflict in the former Yugoslavia: an encyclopedia.Roots of modern conflict. Denver, Colo.:ABC-CLIO.ISBN978-0-87436-935-9.

- Almond, Mark(1994).Europe's backyard war: the war in the Balkans.London:Heinemann.ISBN978-0-434-00003-6.

- Duncan, Walter Raymond; Holman, G. Paul (1994).Ethnic nationalism and regional conflict: the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.Boulder San Francisco Oxford:Westview Press.ISBN978-0-8133-8813-7.

- Glenny, Misha(1996).The fall of Yugoslavia: the third Balkan war(3. ed.). London:Penguin Books.ISBN978-0-14-026101-1.

- LeBor, Adam(2003).Milosevic: a biography.London:Bloomsbury Publishing.ISBN978-0-7475-6181-1.

- Magaš, Branka (1993).The destruction of Yugoslavia: tracking the break-up 1980-92.London, GB: New York Verso.ISBN978-0-86091-593-5.

- Mojzes, Paul (1994).Yugoslavian inferno: ethnoreligious warfare in the Balkans.New York:Continuum Publishers.ISBN978-0-8264-0683-5.

- Radan, Peter (2002).The break-up of Yugoslavia and international law.Routledge studies in international law. London; New York:Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-25352-9.

- Woodward, Susan L.; Brookings Institution (1995).Balkan tragedy: chaos and dissolution after the Cold War.Washington, DC:Brookings Institution.ISBN978-0-8157-9514-8.