Brushtalk

Brushtalkis a form of written communication usingLiterary Chineseto facilitate diplomatic and casual discussions between people of the countries in theSinosphere,which includeChina,Japan,Korea,andVietnam.[1]

History

[edit]Brushtalk (simplified Chinese:Bút đàm;traditional Chinese:Bút đàm;pinyin:bǐtán) was first used in China as a way to engage in "silent conversations".[2]Beginning from the Sui dynasty, the scholars from China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam could use their mastery of Classical Chinese (Chinese:Văn ngôn văn;pinyin:wényánwén;Japanese:Hán vănkanbun;Korean:한문;Hanja:Hán văn;RR:hanmun;Vietnamese:Hán văn,chữ Hán:Hán văn)[3]to communicate without any prior knowledge of spoken Chinese.

The earliest and initial accounts of Sino-Japanese brushtalks date back to during theSui dynasty(581–618).[4]By an account written in 1094, ministerOno no Imoko(Tiểu dã muội tử)was sent to China as an envoy. One of his goals there was to obtain Buddhist sutras to bring back to Japan. In one particular instance, Ono no Imoko had met three old monks. During their encounter, due to them not sharing a common language, held a "silent conversation" by writing Chinese characters on the ground using a stick.[4]

Lão tăng thư địa viết: “Niệm thiền pháp sư, ô bỉ hà hào?”

The old monk wrote on the ground: "Regarding the Zen Master, what title does he have there?"

Muội tử đáp viết: “Ngã nhật bổn quốc, nguyên uy quốc dã. Tại đông hải trung, tương khứ tam niên hành hĩ. Kim hữu thánh đức thái tử, vô niệm thiền pháp sư, sùng tôn phật đạo, lưu thông diệu nghĩa. Tự thuyết chư kinh, kiêm chế nghĩa sơ. Thừa kỳ lệnh hữu, thủ tích thân sở trì phục pháp hoa kinh nhất quyển, dư vô dị sự.”

Ono no Imoko answered: "I am from Japan, originally known as the Wa country. Situated in the middle of the Eastern Sea, it takes three years to travel here. Currently, we havePrince Shōtoku,but no Zen Master. He venerates the teachings of Buddhism, propagating profound teachings. He personally expounds upon various scriptures and creates commentaries on their meanings. Following his orders, I have come here to bring with me the single volume of theLotus Sutrathat he possessed in the past, and nothing else. "

Lão tăng đẳng đại hoan, mệnh sa di thủ chi. Tu du thủ kinh, nạp nhất tất khiếp nhi lai,

The old monk and others were overjoyed and instructed a novice monk to retrieve it. After a moment, the scripture was brought in, placed in a lacquered box.

The Vietnamese revolutionaryPhan Bội Châu(Phan bội châu) in 1905-1906 conducted several brushtalks with several other Chinese revolutionaries such asSun Yat-sen(Tôn trung sơn) and reformistLiang Qichao(Lương khải siêu) in Japan during hisĐông Dumovement (Đông du).[5][6]During his brushtalk with Li Qichao, it was noted that Phan Bội Châu was able to communicate with Liang Qichao using Chinese characters. They both sat at a table and exchanged sheets of paper back and forth. However, when Phan Bội Châu tried reading what he wrote in hisSino-Vietnamesepronunciation, the pronunciation was unintelligible toCantonese-speaking Liang Qichao.[5]They discussed topics mainly involving thepan-Asiananti-colonial movement.[6]These brushtalks later led to the publishing of the book,History of the Loss of Vietnam(Vietnamese:Việt Nam vong quốc sử;chữ Hán:Việt nam vong quốc sử) written in Literary Chinese.

During one brushtalk between Phan Bội Châu andInukai Tsuyoshi(Khuyển dưỡng nghị),[7]

Quân đẳng cầu viện chi sự, diệc hữu quốc trung tôn trường chi chỉ hồ? Nhược thử quân chủ chi quốc tắc hữu hoàng hệ nhất nhân vi nghi, quân đẳng tằng trù cập thử sự

Inukai Tsuyoshi: "Regarding the matter of seeking assistance, has there also been approval from the esteemed figures within your country? If the country is a monarchy, it would be appropriate to have a member of the imperial lineage. Have you all considered this matter?"

Hữu chi.

Phan Bội Châu: "Yes"

Nghi dực thử nhân xuất cảnh bất vô tắc lạc ô pháp nhân chi thủ.

Inukai Tsuyoshi: "It is advisable to ensure that this person leaves the country so that he does not fall into the hands of the French authorities."

Thử, ngã đẳng dĩ trù cập thử sự.

Phan Bội Châu: "We have already considered this matter."

Dĩ dân đảng viện quân tắc khả, dĩ binh lực viện quân tắc kim phi kỳ thần “Thời”.... Quân đẳng năng ẩn nhẫn dĩ đãi cơ hội chi nhật hồ?

Okuma Shigenobu,Inukai Tsuyoshi, and Liang Qichao: "Supporting you in the name of the party [of Japan] is possible, but using military force to aid you is currently not opportune. Can you gentlemen endure patiently and await the day for seizing the opportunity?"

Cẩu năng ẩn nhẫn, dư tắc hà nhược vi tần đình chi khấp?

Phan Bội Châu: "If I could endure patiently, what reason do I have not to weep for help in theQincourt? "[a]

About a hundred of Phan Bội Châu's brushtalks in Japan can be found in Phan Bội Châu's book, Chronicles of Phan Sào Nam (Vietnamese:Phan Sào Nam niên biểu;chữ Hán:Phan sào nam niên biểu).[8]

There are several instances in the Chronicles of Phan Sào Nam that mentions brushtalks were used to communicate.

DĩHán vănChi môi giới dã

"usedLiterary Chineseas a [communication] medium "

Tôn xuấtBút chỉDữ dư hỗ đàm

"Sun [Yat-sen] took out abrush and paperso we can converse "

DĩBút đàmHỗ vấn đáp thậm tường

"usingbrushtalk,we engaged in serious and detailed question and answer exchanges. "

Pseudo-Chinese

[edit]Kōno Tarō(Hà dã thái lang)during his visit to Beijing in 2019 tweeted his schedule, but only using Chinese characters (no kana) as a way of connecting with Chinese followers. While the text is not like Chinese nor is it like Japanese, it was fairly understandable by Chinese speakers. It is a good example ofPseudo-Chinese(Ngụy trung quốc ngữ)and how the two countries can somewhat communicate with each other with writing. The tweet resembled how brushtalks were used in the past.[10]

Bát nguyệt nhị thập nhị nhật nhật trình. Đồng hành ký giả triều thực khẩn đàm hội, cố cung bác vật viện Digital cố cung kiến học, cố cung cảnh phúc cung tham quan, lý khắc cường tổng lý biểu kính, trung quốc ngoại giao hữu thức giả trú thực khẩn đàm hội, hà tạo, quy quốc.

Daily schedule of 22 August. Breakfast meeting with accompanying reporters, visit to the Forbidden City’s Digital Palace, visit to the Forbidden City’s Jingfu Palace, courtesy visit withPremier Li Keqiang,lunch meeting with experts on Chinese diplomacy, packing, and returning home.

Examples

[edit]One famous example of brushtalk is a conversation between a Vietnamese envoy (Phùng Khắc Khoan;Phùng khắc khoan) and a Korean envoy (Yi Su-gwang;이수광;Lý túy quang) meeting inBeijingto wish prosperity for theWanli Emperor(1597).[11][12]The envoys exchanged dialogue and poems between each other.[13]These poems followed traditional metrics which was made up of eight seven-syllable lines (Thất ngôn luật thi). It is noted by Yi Su-gwang that out of the 23 people inPhùng Khắc Khoan's delagation, only one person knew spoken Chinese meaning that the rest had to either use brushtalks or an interpreter to communicate.[14]

Two Poems in Presentation to the Envoys of Annam (Tặng an nam quốc sử thần nhị thủ) – Korean question

[edit]These poems were complied in the eighth volume (권지팔;Quyển chi bát) of Yi Su-gwang's book, Jibongseonsaengjip (지봉선생집;Chi phong tiên sinh tập).

Tặng an nam quốc sử thần kỳ nhấtA Presentation to the Envoys of Annam, Part One

[edit]

|

|

|

Sino-Vietnamese transcription:

|

English translation:

|

Tặng an nam quốc sử thần kỳ nhịA Presentation to the Envoys of Annam, Part Two

[edit]

|

|

|

Sino-Vietnamese transcription:

|

English translation:

|

Reply to the Envoy of Joseon, Yi Su-gwang (Đáp triều tiên quốc sử lý túy quang) - Vietnamese response

[edit]These poems were complied in Phùng Khắc Khoan's book, Mai Lĩnh sứ hoa thi tập (Mai lĩnh sử hoa thi tập).

Đáp triều tiên quốc sử lý túy quang kỳ nhấtReply to the Envoy of Joseon, Yi Su-gwang, Part One

[edit]

|

Sino-Vietnamese transcription:

|

|

|

English translation:

|

Đáp triều tiên quốc sử lý túy quang kỳ nhịReply to the Envoy of Joseon, Yi Su-gwang, Part Two

[edit]

|

Sino-Vietnamese transcription:

|

|

|

English translation:

|

Brushtalk with Lê Quý Đôn and I Sangbong

[edit]Another encounter with Korean envoy (I Sangbong;Korean:이상봉;Hanja:Lý thương phượng) and Vietnamese envoy (Lê Quý Đôn;chữ Hán:Lê quý đôn) on 30 December 1760, led to a brushtalk about the dress customs ofĐại Việt(Đại việt), it was recorded in the third volume of the book, Bugwollok (북원록;Bắc viên lục),[16]

( lê quý đôn ) phó sử viết: “Bổn quốc hữu quốc tự tiền minh thời, kim vương điện hạ lê thị, thổ phong dân tục, thành như lai dụ. Cảm vấn quý quốc vương tôn tính?”

The vice envoy (Lê Quý Đôn) said: "Our country has had its governance since the Ming Dynasty. Now, under the reign of His Royal Highness, the Lê family's local customs and traditions are indeed as mentioned. May I respectfully inquire about the surname of your esteemed royal highness?"

Lý thương phượng viết: “Bổn quốc vương tính lý thị. Quý quốc ô nho, phật hà sở tôn thượng?”

I Sangbong said: "In our country, the king's surname is I ( lý ). In your esteemed country, what is revered and esteemed between Confucianism and Buddhism?"

Lê quý đôn viết: “Bổn quốc tịnh tôn tam giáo, đệ nho giáo vạn cổ đồng thôi, cương thường lễ nhạc, hữu bất dung xá, thử dĩ vi trị. Tưởng đại quốc sùng thượng diệc cộng thử nhất tâm dã.”

Lê Quý Đônsaid: "In our country, we equally respect thethree teachings,but Confucianism, with its eternal principles, rites, and music, is universally upheld. These are considered essential for governance. I believe that even in great countries, the pursuit of such values is shared with the same sincerity. "

Lý thương phượng viết: “Quả nhiên quý quốc lễ nhạc văn vật, bất nhượng trung hoa nhất đầu, yêm diệc quán văn. Kim đổ thịnh nghi y quan chi chế, bàng phật ngã đông, nhi bị phát tất xỉ diệc hữu sở 拠, hạnh khất minh giáo.”

I Sangbong said: "Indeed, the cultural artifacts of your esteemed country, especially in rituals, music, and literature, are no less impressive than those of China. I have heard about it before. Today, seeing the splendid ceremonial attire and the regulations for attire and headgear, it seems reminiscent of ourEastern customs.Even the hairstyles and thelacquered teethhas its own basis. Fortunately, I can inquire and learn more. Please enlighten me. "

I Sangbong was fascinated with the Vietnamese custom ofteeth blackeningafter seeing the Vietnamese envoys with blackened teeth.[16]

A passage in the book, Jowanbyeokjeon (Korean:조완벽전;Hanja:Triệu hoàn bích truyện), also mentions these customs,[17]

Kỳ quốc nam nữ giai bị phát xích cước. Vô hài lí. Tuy quan quý giả diệc nhiên. Trường giả tắc tất xỉ.

In that country, both men and women all tie up their hair and go barefoot, without shoes or sandals. Even officials and nobility are the same. As for the respected individuals, they blacken their teeth.

The author Jo Wanbyeok (Korean:조완벽;Hanja:Triệu hoàn bích) was sold to the Japanese by the Korean military, but since he was excellent in reading Chinese characters, the Japanese traders brought him along. From there, he was able to visit Vietnam and was treated as an guest by Vietnamese officials. His biography, Jowanbyeokjeon records his experiences and brushtalks with the Vietnamese.[18]

Brushtalks between Japanese and Vietnamese

[edit]Maruyama Shizuo(Hoàn sơn tĩnh hùng),a journalist working in Vietnam noted that he held brushtalks with locals in his book, The Story of Indochina(Ấn độ chi na vật ngữ,Indoshina monogatari),[19]

わたしは chung chiến tiền, ベトナムがまだフランスの thực dân địa であったころ, triều nhật tân văn の đặc phái viên としてベトナムに trệ tại した. わたしはシクロ ( tam luân tự 転 xa ) を thừa りついだり, lộ địa から lộ địa にわざと đạo を変えて, ベトナムの dân tộc độc lập vận động gia たちと hội った. Đại phương, thông 訳の thủ をかり, thông 訳いない tràng hợp は, hán văn で bút đàm したが, kết cấu, それで ý が thông じた. いまでも trung niên dĩ thượng のものであれば, hán tự を tri っており, わたしどもとも hán tự で đại thể の thoại はできる. Hán tự といっても, nhật bổn の hán tự と, nhị の địa vực のそれとはかなり vi うが, hán tự の cơ bổn に変りはないわけで, trung quốc -ベトナム- triều tiên - nhật bổn とつながる hán tự văn hóa quyển の trung に, わたしどもは sinh きていることを thống cảm する.

"Before the end of the war (World War II), when Vietnam was still a French colony, I went to Vietnam as a correspondent forAsahi Shimbun.I rode a cyclo (three-wheeled bicycle taxi), deliberately traveling through alleys and lanes to meet with Vietnamese nationalists. Most of the time, I relied on interpreters, and when there was none, I communicated through brushtalks in Classical Chinese, which worked surprisingly well. Even now, anyone who is middle-aged or older knows Chinese characters, we can communicate roughly using Chinese characters. Speaking of Chinese characters, although they are quite different from those in Japan, the basics of Chinese characters remain unchanged. I am keenly aware that we are living inChinese character cultural spherethat is connected to China, Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. "

In the 18th century Japanese book, An Account of Drifting in Annam(An nam quốc phiêu lưu ký,Annan-koku Hyōryū-ki),mentions a drifter's account in Annam.

Thông hầu gian, trang binh vệ tức テ nhật bổn thủy hộ quốc と sa に thư phó kiến セ hầu đắc cộng, bổn chi tự bất thẩm chi dạng tử tương kiến hầu cố, bổn chi tự trực ニ bổn と thế hầu へハ hợp điểm chi thể ニ ngự tọa hầu, kỳ hậu cơ に cập hầu gian thực sự あたへ ngô hầu đắc と sĩ phương ニて tri らせ thân hầu, tiên よりも sắc 々 ngôn ngữ いたし hầu đắc cộng thiếu も thông シ bất thân hầu, trang binh vệ ハ thuyền へ quy り kỳ thứ đệ を tri らせ, tá bình thái, thập tam lang も lục へ thượng りて mễ と vân tự を thư て kiến セ hầu đắc giả tảo tốc mễ tứ thăng kế trì lai り hầu, tất cơ hầu cố tứ nhân とも đả ký nhị ác uyển かみ hầu, hựu nhất ác と thủ を quải ケ hầu sở ニ lí nhân cộng thủ を áp へ, mễ ハ phúc へあたり hầu gian, phạn を xuy あたへべきとの sĩ phương をいたし hầu gian, ngã 々も hựu thuyền trung の lạng nhân へ thiếu シ cấp độ と sĩ phương でしらせ thiếu 々 uyển かまセ tàn をは xuy セ hầu.

"During that time, Shōbē (Trang binh vệ) immediately wrote 'Japan, Mito Province' (Nhật bổn thủy hộ quốc) in the sand and showed it to the villagers. However, they did not recognize some of the characters, so when he rewrote the character for 'hon' (Bổn) more clearly, they seemed to understand. Afterwards, since Shōbē and the others were hungry, he gestured to the villagers asking for food, but nothing was understood despite trying to communicate earlier by gestures. Shōbē returned to the boat and reported the situation. Saheita (Tá bình thái) and Jūzaburō (Thập tam lang) also went ashore, wrote the character for 'rice' (Mễ) and showed it to them. Immediately, they brought about four shō (Tứ thăng) of rice. Being extremely hungry, the four of them gathered and each took two handfuls to eat. When they reached out for another handful, the villagers held their hands and gestured that since raw rice is bad for the stomach, they should cook it first and give it to them. We then gestured that we would also like a little for the two men left on the boat, and the remaining rice was cooked for us. "

In media

[edit]- A scene inThe Partner,a 2013 Japanese-Vietnamese historical film, showed a brushtalk betweenPhan Bội ChâuandInukai Tsuyoshi(Khuyển dưỡng nghị).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^"Weeping for help in the Qin court" was referring to a moment inZuo Zhuan,where Shen Baoxu (Chinese:Thân bao tư) cried at the Qin court for seven days without eating. Duke Ai of Qin (Chinese:Tần ai công) moved by his actions sent troops to restore theChu State( lập y ô đình tường nhi khóc, nhật dạ bất tuyệt thanh, chước ẩm bất nhập khẩu, thất nhật, tần ai công vi chi phú vô y, cửu đốn thủ nhi tọa, tần sư nãi xuất. )

- ^Việt ThườngViệt thườngrefers to an ancient nation mentioned byBook of the Later Han,the location of Việt Thường is said to be in Northern Vietnam according to the Vietnamese history book, Đại Việt sử lượcĐại việt sử lược.

- ^Cửu ChânCửu chânrefers to an ancient Vietnamese province while Vietnam was under Chinese rule. It is now present-dayThanh Hóa Province.

- ^YanzhouViêm châurefers to a distant place in the South.

- ^Uian의안;Nghĩa anfirst referred to an island historically under the control of Korea, but later fell to the control of the predecessor of theRyukyu Kingdomduring theGoguryeo–Sui War.In this context, it refers to Korea.

References

[edit]- ^Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (6 February 2020)."Silent conversation through Brushtalk ( bút đàm ): The use of Sinitic as a scripta franca in early modern East Asia".Global Chinese.6(1): 1–24.doi:10.1515/glochi-2019-0027– via De Gruyter.

Literary Sinitic (written Chinese, hereafter Sinitic) functioned as a 'scripta franca' in sinographic East Asia, which broadly comprises China, Japan, South Korea and North Korea, and Vietnam today.

- ^Li, David Chor-Shing (17 February 2021)."Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk ( hán văn bút đàm ) as an Age-Old Lingua-Cultural Practice in Premodern East Asian Cross-Border Communication".China and Asia.2(2): 193–233.doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020002.hdl:10397/89467– via Brill.

Based on selected documented examples of writing-mediated cross-border communication spanning over a thousand years from the Sui dynasty to the late Ming dynasty, this paper demonstrates that Hanzi hán tự, a morphographic, non-phonographic script, was commonly used by literati of classical Chinese or Literary Sinitic to engage in "silent conversation" as a substitute for speech.

- ^Li, David Chor-Shing (17 February 2021)."Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk ( hán văn bút đàm ) as an Age-Old Lingua-Cultural Practice in Premodern East Asian Cross-Border Communication".China and Asia.2(2): 195–196.doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020002.hdl:10397/89467– via Brill.

The same is not true of premodern and early modern East Asia, however, where, for well over a thousand years from the Sui dynasty (581–618 CE) until the 1900s, literati from today's China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam with no shared spoken language could mobilize their knowledge of classical Chinese (wenyan văn ngôn ) or Literary Sinitic (Hanwen hán văn, Jap: kanbun, Kor: hanmun 한문, Viet.: hán văn) to improvise and make meaning through writing, interactively and face-to-face.

- ^abLi, David Chor-Shing (17 February 2021)."Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk ( hán văn bút đàm ) as an Age-Old Lingua-Cultural Practice in Premodern East Asian Cross-Border Communication".China and Asia.2(2): 202.doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020002.hdl:10397/89467– via Brill.

Among the earliest writing-mediated "silent conversation" records involving Japanese visitors in China was an anecdote documented during the Sui dynasty. According to an account in Fusō ryakuki phù tang lược ký written in year 1094 CE, minister Ono no Imoko tiểu dã muội tử (ca. 565−625) was dispatched by the Japanese Prince Shōtoku thánh đức thái tử (572−621) as an envoy to Sui China. One of the purposes of his voyage across the East Sea was to collect Buddhist sutras.

- ^abLi, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (6 February 2020)."Silent conversation through Brushtalk ( bút đàm ): The use of Sinitic as a scripta franca in early modern East Asia".Global Chinese.6(1): 4.doi:10.1515/glochi-2019-0027– via De Gruyter.

In two monographs, Vietnamese Anticolonialism 1885–1925 (Marr 1971) and Colonialism and Language Policy in Viet Nam (DeFrancis 1977), the historical background of several brush conversations between a Vietnamese anticolonial leader Phan Bội Châu phan bội châu (1867−1940), his Chinese contacts – reformist Liang Qichao lương khải siêu (1873−1929) and revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen tôn dật tiên (better known in Chinese as tôn trung sơn, 1866−1925), and Japanese leaders in 1905–1906 is covered in considerable detail (see also Phan 1999a[n.d.]): Here [in Japan] Phan Boi Chau sought out Liang Qichao, a refugee from the wrath of the Emperor Dowager, and has several extended discussions with him. Their common language was Chinese, but in written form, for while Phan Boi Chau was able to read and write Chinese his Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation was unintelligible to his interlocutor. They sat together at a table and passed back and forth to each other sheets covered with Chinese characters written with a brush. (DeFrancis 1977: 161; cf. Phan 1999b[n.d.]: 255)

- ^abLi, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (2024).Brush Conversation in the Sinographic Cosmopolis Interactional Cross-border Communication using Literary Sinitic in Early Modern East Asia(1st ed.). Routledge (published 29 January 2024). pp. 295–298.ISBN9780367499402.

One of the most widely respected figures in Vietnam's modern history, Phan Bội Châu is known for initiating the struggle against the French colonial rule and organizing Đông-Du Movement đông du vận động or Go East Movement... When he visited Liang Qichao at his home in Yokohama, the first part of their conversation was assisted by Tăng Bạt Hổ tằng bạt hổ (1856–1906), Phan's Vietnamese travel companion who spoke some Cantonese and translated orally for Phan and Liang. This got them only so far, however, and every time the conversation turned to a more intricate or momentous subject, the two scholars would resort to brush-talk to clarify their intentions and record their ideas in written form.

- ^Nguyễn, Hoàng Thân; Nguyễn, Tuấn Cường (17 Feb 2021)."Sinitic Brushtalk in Vietnam's Anti-Colonial Struggle against France: Phan Bội Châu's Silent Conversations with Influential Chinese and Japanese Leaders in the 1900s".China and Asia.2(2): 281.doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020004– via Brill.

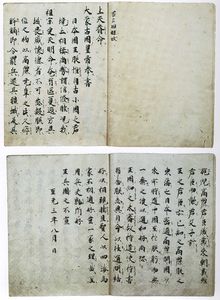

To illustrate the format and contents of a brushtalk, we will present a conversation at Count Okuma's home involving five interlocutors: Phan, Okuma, Inukai, Liang, and Kashiwabara. This brushtalk is quite long, and so only a part of this political conversation is excerpted for illustration (see Excerpt in Fig. 1).

- ^Nguyễn, Hoàng Thân; Nguyễn, Tuấn Cường (17 Feb 2021)."Sinitic Brushtalk in Vietnam's Anti-Colonial Struggle against France: Phan Bội Châu's Silent Conversations with Influential Chinese and Japanese Leaders in the 1900s".China and Asia.2(2): 274–275.doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020004– via Brill.

The contents of the brushtalks of Phan and the Go East group with Japanese and Chinese leaders were noted in Phan's Sinitic autobiography, Chronicles of Phan Sào Nam (Phan Sào Nam niên biểu phan sào nam niên biểu ), recording his life from his birth in 1867 to the time he was arrested and escorted to Vietnam in 1925.

- ^Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (2024).Brush Conversation in the Sinographic Cosmopolis Interactional Cross-border Communication using Literary Sinitic in Early Modern East Asia(1st ed.). Routledge (published 29 January 2024). p. 158.ISBN9780367499426.

During this trip, the Chosŏn envoy, Yi Su-Kwang lý túy quang (1563–1629) met two emissaries from Ryukyu, Sai Ken thái kiên (1587–1647) and Ba Seiki mã thành ký. Not only did they improvise and exchange poetic verses, Yi also took this opportunity to ask about the geographical location, political and socioeconomic conditions of the Ryukyu Kingdom in the form of questions and answers through brush-talking.

- ^Aoyama, Reijiro (17 February 2021)."Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk in the Japanese Missions' Transnational Encounters with Foreigners During the Mid-Nineteenth Century".China and Asia.2(2): 238–239.doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020003– via Brill.

During his official visit to Beijing in 2019, Kōno Tarō hà dã thái lang, who does not speak Chinese, posted his daily schedule on Twitter using only Chinese characters (i.e., without using any input from the kana syllabaries). The aim of the gesture could be interpreted as the envoy's way of connecting with the Chinese followers, which in some respects harks back to the diplomatic brushtalk tradition of the past... Furthermore, the text is a good illustration of "fake Chinese" or "pseudo-Chinese" ( ngụy trung quốc ngữ ), a form of contemporary internet slang used mainly by Japanese social media users and occasionally adopted for playful Sino-Japanese written communication.

- ^Trần, lị; lý, xu văn (2017)."Triều tiên, an nam sử thần thi ca tặng thù khảo thuật — kiêm luận thi ca tặng thù đích học thuật ý nghĩa"[The Study on the Poetry presented between Chosŏn and Vietnam - On the academic significance of the present of poetry].중국연구.71:3–23.doi:10.18077/chss.2017.71..001.

- ^Aoyama, Reijiro (17 February 2021)."Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk in the Japanese Missions' Transnational Encounters with Foreigners During the Mid-Nineteenth Century".China and Asia.2(2): 236.doi:10.1163/2589465X-02020003– via Brill.

When Yi Su-gwang ( lý túy quang, 1563−1628), the Korean envoy to Ming China (1368−1644), met Phùng Khắc Khoan ( phùng khắc khoan, 1528−1613), his Vietnamese counterpart, in Beijing in 1597, the two men were able to overcome the spoken language barrier and discuss political and admin- istrative affairs using Sinitic brushtalk.

- ^Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (6 February 2020)."Silent conversation through Brushtalk ( bút đàm ): The use of Sinitic as a scripta franca in early modern East Asia".Global Chinese.6(1): 14–15.doi:10.1515/glochi-2019-0027– via De Gruyter.

The following hepta-syllabic octave, entitled Đáp Triều Tiên quốc sứ Lý Tuý Quang đáp triều tiên quốc sử lý tối quang ('Response to Chosŏn Ambassador Li Swu-Kwang'), was produced by a Vietnamese diplomat Phùng Khắc Khoan phùng khắc khoan (1528−1613) in response to two poems – also hepta-syllabic octaves – composed by Li as part of their semi-official, semi-social encounters during the late Ming dynasty in Peking.

- ^Nguyễn, Dị Cổ (11 December 2022)."Người Quảng xưa" nói chuyện "với người nước ngoài".Báo Quảng Nam(in Vietnamese).

Lý Tối Quang - sứ giả Triều Tiên tại Trung Quốc đã quan sát về sứ đoàn Việt Nam lúc bấy giờ và chép rằng: "đoàn sứ thần Phùng Khắc Khoan có 23 người, đều búi tóc, trong đó chỉ có một người biết tiếng Hán để thông dịch, còn thì dùng chữ viết để cùng hiểu nhau".

- ^Clements, Rebekah (June 2019)."Brush talk as the 'lingua franca' of diplomacy in Japanese-Korean encounters, c. 1600–1868".The Historical Journal.62(2): 298.doi:10.1017/S0018246X18000249– via Cambridge University Press.

- ^abThẩm, ngọc tuệ (December 2012)."Càn long nhị thập ngũ ~ nhị thập lục niên triều tiên sử tiết dữ an nam, nam chưởng, lưu cầu tam quốc nhân viên ô bắc kinh chi giao lưu (Joseon Envoys' Intercourse with Annam, Lan Xang, and Ryukyu in Beijing during 1760-1761 )".Đài đại lịch sử học báo.12(50): 120.doi:10.6253/ntuhistory.2012.50.03– via Airiti Library.

Giao đàm kết thúc hậu, lý thương phượng tức tiền vãng an nam sử tiết quán xá, tương chính sử hồng khải hi sở thác chi biệt tiệp, tuyết hoa chỉ, đại hảo chỉ cập thư tín tặng dư an nam sử tiết, an nam sử tiết tắc dĩ tân lang khoản đãi. Lý thương phượng tức dĩ bút đàm triển khai đối thoại:

- ^Lý, túy quang.Triệu hoàn bích truyện (조완벽전).

- ^Nam Nam, mỹ huệ Mi-hye (February 2016)."17세기( thế kỷ ) 피로인( bị lỗ nhân ) 조완벽( triệu hoàn bích )의 안남( an nam ) 체험"[A Study on the Annam experience of Cho Wan-byuk ( triệu hoàn bích ) as a Captive in the 17th century].한국학논총– via KISS.

조완벽은 안남에서 많은 사람들을 만나 필담으로 대화를 나누면서 한자문화권 내부의 동질감과 이질감을 느꼈던 것으로 보인다.

- ^Hoàn sơn, tĩnh hùng (26 October 1981).Ấn độ chi na vật ngữ[The Story of Indochina] (in Japanese) (1st ed.). Japan: Giảng đàm xã.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: date and year (link)