Bubonic plague

| Bubonic plague | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abuboon the upper thigh of a person infected with bubonic plague | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever,headaches,vomiting,swollen lymph nodes[1][2] |

| Complications | Gangrene, meningitis[3] |

| Usual onset | 1–7 days after exposure[1] |

| Causes | Yersinia pestisspread byfleas[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Finding the bacterium in the blood,sputum,or lymph nodes[1] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics such asstreptomycin,gentamicin,ordoxycycline[4][5] |

| Frequency | 650 cases reported a year[1] |

| Deaths | 10% mortality with treatment[4] 30–90% if untreated[1][4] |

Bubonic plagueis one of three types ofplaguecaused by thebacteriumYersinia pestis.[1]One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria,flu-like symptomsdevelop.[1]These symptoms includefever,headaches,andvomiting,[1]as well asswollen and painful lymph nodesoccurring in the area closest to where the bacteria entered the skin.[2]Acral necrosis,the dark discoloration of skin, is another symptom. Occasionally, swollen lymph nodes, known as "buboes",may break open.[1]

The three types of plague are the result of the route of infection: bubonic plague,septicemic plague,andpneumonic plague.[1]Bubonic plague is mainly spread by infectedfleasfrom smallanimals.[1]It may also result from exposure to the body fluids from a dead plague-infected animal.[6]Mammals such asrabbits,hares,and somecatspecies are susceptible to bubonic plague, and typically die upon contraction.[7]In the bubonic form of plague, the bacteria enter through the skin through a flea bite and travel via thelymphatic vesselsto alymph node,causing it to swell.[1]Diagnosis is made by finding the bacteria in the blood,sputum,or fluid from lymph nodes.[1]

Prevention is through public health measures such as not handling dead animals in areas where plague is common.[8][1]Whilevaccines against the plaguehave been developed, theWorld Health Organizationrecommends that only high-risk groups, such as certain laboratory personnel and health care workers, get inoculated.[1]Severalantibioticsare effective for treatment, includingstreptomycin,gentamicin,anddoxycycline.[4][5]

Without treatment, plague results in the death of 30% to 90% of those infected.[1][4]Death, if it occurs, is typically within 10 days.[9]With treatment, the risk of death is around 10%.[4]Globally between 2010 and 2015 there were 3,248 documented cases, which resulted in 584 deaths.[1]The countries with the greatest number of cases are theDemocratic Republic of the Congo,Madagascar,andPeru.[1]

The plague is considered the likely cause of theBlack Deaththatswept through Asia, Europe, and Africain the 14th century and killed an estimated 50 million people,[1][10]including about 25% to 60% of the European population.[1][11]Because the plague killed so many of the working population, wages rose due to the demand for labor.[11]Some historians see this as a turning point inEuropean economic development.[11]The disease is also considered to have been responsible for thePlague of Justinian,originating in theEastern Roman Empirein the 6th century CE, as well as thethird epidemic,affectingChina,Mongolia,andIndia,originating in theYunnan Provincein 1855.[12]The termbubonicis derived from the Greek wordβουβών,meaning'groin'.[13]

Cause

The bubonic plague is an infection of thelymphatic system,usually resulting from the bite of an infected flea,Xenopsylla cheopis(theOriental rat flea).[14]Several flea species carried the bubonic plague, such asPulex irritans(thehuman flea),Xenopsylla cheopis,andCeratophyllus fasciatus.[14]Xenopsylla cheopiswas the most effective flea species for transmission.[14]

The flea is parasitic on house and field rats and seeks out other prey when its rodent host dies. Rats were an amplifying factor to bubonic plague due to their common association with humans as well as the nature of their blood.[15]The rat's blood allows the rat to withstand a majorconcentrationof the plague.[15]The bacteria form aggregates in the gut of infected fleas, and this results in the flea regurgitating ingested blood, which is now infected, into the bite site of a rodent or human host. Once established, the bacteria rapidly spread to thelymph nodesof the host and multiply. The fleas that transmit the disease only directly infect humans when the rat population in the area is wiped out from a mass infection.[16]Furthermore, in areas with a large population of rats, the animals can harbor low levels of the plague infection without causing human outbreaks.[15]With no new rat inputs being added to the population from other areas, the infection only spread to humans in very rare cases of overcrowding.[15]

Signs and symptoms

After being transmitted via the bite of an infected flea, theY. pestisbacteria become localized in an inflamedlymph node,where they begin to colonize and reproduce. Infected lymph nodes develop hemorrhages, which result in the death of tissue.[17]Y. pestisbacillican resist phagocytosis and even reproduce insidephagocytesand kill them. As the disease progresses, the lymph nodes canhemorrhageand become swollen andnecrotic.Bubonic plague can progress to lethalsepticemic plaguein some cases. The plague is also known to spread to the lungs and become the disease known as thepneumonic plague.Symptoms appear two to seven days after getting bitten and they include:[14]

- Chills

- General ill feeling (malaise)

- Highfever>39°C(102.2°F)

- Muscle cramps[17]

- Seizures

- Smooth, painful lymph gland swelling called a bubo, commonly found in the groin, but may occur in the armpits or neck, most often near the site of the initial infection (bite or scratch)

- Pain may occur in the area before the swelling appears

- Gangreneof the extremities such as toes, fingers, lips, and tip of the nose.[18]

The best-known symptom of bubonic plague is one or more infected, enlarged, and painful lymph nodes, known asbuboes.Buboes associated with the bubonic plague are commonly found in the armpits, upper femoral area, groin, and neck region. These buboes will grow and become more painful over time, often to the point of bursting.[19]Symptoms include heavy breathing, continuous vomiting of blood (hematemesis), aching limbs, coughing, and extreme pain caused by the decay or decomposition of the skin while the person is still alive. Additional symptoms include extreme fatigue, gastrointestinal problems, spleen inflammation, lenticulae (black dots scattered throughout the body), delirium,coma,organ failure, and death.[20]Organ failure is a result of the bacteria infecting organs through the bloodstream.[14]Other forms of the disease includesepticemic plagueandpneumonic plague,in which the bacterium reproduces in the person's blood and lungs respectively.[21]

Diagnosis

Laboratory testing is required in order todiagnoseand confirm plague. Ideally, confirmation is through the identification ofY. pestisculturefrom a patient sample. Confirmation of infection can be done by examiningserumtaken during the early and late stages ofinfection.To quickly screen for theY. pestisantigenin patients, rapiddipsticktests have been developed for field use.[22]

Samples taken for testing include:[23]

- Buboes: Swollen lymph nodes (buboes) characteristic of bubonic plague, a fluid sample can be taken from them with a needle.

- Blood:blood culturestest blood samples for bacteria to find source of infection[24]

- Lungs:Spirometrytest are used to screen the lungs for diseases that affect the airways. Chest X-rays of the lungs are also used as an effective method of diagnosis.[25]

Prevention

Bubonic plague outbreaks are controlled by pest control and modern sanitation techniques. This disease uses fleas commonly found on rats as a vector to jump from animals to humans. The mortality rate is highest in the summer and early fall.[26]The successful control of rat populations in dense urban areas is essential to outbreak prevention. One example is the use of a machine called theSulfurozador,used to deliversulphur dioxideto eradicate the pest that spread the bubonic plague in Buenos Aires, Argentina during the early 18th century.[27]Targetedchemoprophylaxis,sanitation,andvector controlalso played a role in controlling the 2003Oranoutbreak of the bubonic plague.[28]Another means of prevention in large European cities was a city-wide quarantine to not only limit interaction with people who were infected, but also to limit the interaction with the infected rats.[29]

Treatment

Several classes ofantibioticare effective in treating bubonic plague. These includeaminoglycosidessuch asstreptomycinandgentamicin,tetracyclines(especiallydoxycycline), and thefluoroquinoloneciprofloxacin.Mortality associated with treated cases of bubonic plague is about 1–15%, compared to a mortality of 40–60% in untreated cases.[30]

People potentially infected with the plague need immediate treatment and should be given antibiotics within 24 hours of the first symptoms to prevent death. Other treatments include oxygen, intravenous fluids, and respiratory support. People who have had contact with anyone infected by pneumonic plague are given prophylactic antibiotics.[31]Using the broad-based antibiotic streptomycin has proven to be dramatically successful against the bubonic plague within 12 hours of infection.[32]

Epidemiology

Globally between 2010 and 2015, there were 3,248 documented cases, which resulted in 584 deaths.[1]The countries with the greatest number of cases are theDemocratic Republic of the Congo,Madagascar,andPeru.[1]

For over a decade since 2001, Zambia, India, Malawi, Algeria, China, Peru, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo had the most plague cases, with over 1,100 cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo alone. From 1,000 to 2,000 cases are conservatively reported per year to theWHO.[33]From 2012 to 2017, reflecting political unrest and poor hygienic conditions, Madagascar began to host regular epidemics.[33]

Between 1900 and 2015, the United States had 1,036 human plague cases, with an average of 9 cases per year. In 2015, 16 people in the western United States developed plague, including 2 cases inYosemite National Park.[34]These US cases usually occur in rural northern New Mexico, northern Arizona, southern Colorado, California, southern Oregon, and far western Nevada.[35]

In November 2017, the Madagascar Ministry of Health reportedan outbreakto the WHO (World Health Organization) with more cases and deaths than any recent outbreak in the country. Unusually, most of the cases werepneumonicrather than bubonic.[36]

In June 2018, a child was confirmed to be the first person inIdahoto be infected by bubonic plague in nearly 30 years.[37]

A couple died in May 2019, in Mongolia, while huntingmarmots.[38]Another two people in the province of Inner Mongolia, China, were treated in November 2019 for the disease.[39]

In July 2020, inBayannur,Inner Mongoliaof China, a human case of bubonic plague was reported. Officials responded by activating a city-wide plague-prevention system for the remainder of the year.[40]Also in July 2020, in Mongolia, a teenager died from bubonic plague after consuming infected marmot meat.[41]

History

Yersinia pestishas been discovered in archaeological finds from the Late Bronze Age (~3800BP).[42]The bacteria is identified by ancient DNA in human teeth from Asia and Europe dating from 2,800 to 5,000 years ago.[43]Some authors have suggested that the plague was responsible for theNeolithic decline.[44]

First pandemic

The first recorded epidemic affected theSasanian Empireand their arch-rivals, theEastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire)and was named thePlague of Justinian(541–549 AD) after emperorJustinian I,who was infected but survived through extensive treatment.[45][46]The pandemic resulted in the deaths of an estimated 25 million (6th century outbreak) to 50 million people (two centuries of recurrence).[47][48]The historianProcopiuswrote, in Volume II ofHistory of the Wars,of his personal encounter with the plague and the effect it had on the rising empire.

In the spring of 542, the plague arrived in Constantinople, working its way from port city to port city and spreading around theMediterranean Sea,later migrating inland eastward into Asia Minor and west into Greece and Italy. The Plague of Justinian is said to have been "completed" in the middle of the 8th century.[15]Because the infectious disease spread inland by the transferring of merchandise through Justinian's efforts in acquiring luxurious goods of the time and exporting supplies, his capital became the leading exporter of the bubonic plague. Procopius, in his workSecret History,declared that Justinian was a demon of an emperor who either created the plague himself or was being punished for his sinfulness.[48]

Second pandemic

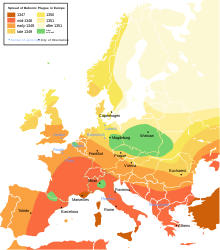

Medieval society's increasing population was put to deadly halt when, in theLate Middle Ages,Europe experienced the deadliest disease outbreak in history. They called it the Great Dying or The Great Pestilence, later coined The Black Death.[19]Lasting in potency for roughly six years, 1346–1352, the Black Death claimed one-third of the European human population, with mortality rates as high as 70%–80%.[19]Some historians believe that society subsequently became more violent as the mass mortality rate cheapened life and thus increased warfare, crime, popular revolt, waves offlagellants,and persecution.[49]The Black Death originated in Central Asia and spread from Italy and then throughout other European countries. Arab historians Ibn Al-Wardni and Almaqrizi believed the Black Death originated in Mongolia. Chinese records also show a huge outbreak inMongoliain the early 1330s.[50]

In 2022, researchers presented evidence that the plague originated near LakeIssyk-KulinKyrgyzstan.[51]The Mongols had cut the trade route (theSilk Road) between China and Europe, which halted the spread of the Black Death from eastern Russia to Western Europe. The European epidemic may have begun with thesiege of Caffa,an attack thatMongolslaunched on the Italian merchants' last trading station in the region,Caffa,in theCrimea.[32]

In late 1346, plague broke out among thebesiegersand from them penetrated the town. The Mongol forces catapulted plague-infested corpses into Caffa as a form of attack, one of the first known instances ofbiological warfare.[52]When spring arrived, the Italian merchants fled on their ships, unknowingly carrying the Black Death. Carried by the fleas on rats, the plague initially spread to humans near the Black Sea and then outwards to the rest of Europe as a result of people fleeing from one area to another. Rats migrated with humans, traveling among grain bags, clothing, ships, wagons, and grain husks.[20]Continued research indicates thatblack rats,those that primarily transmitted the disease, prefer grain as a primary meal.[15]Due to this, the major bulk grain fleets that transported major city's food shipments from Africa andAlexandriato heavily populated areas, and were then unloaded by hand, played a role in increasing the transmission effectiveness of the plague.[15]

Third pandemic

The plague resurfaced for a third time in the mid-19th century; this is also known as "the modern pandemic". Like the two previous outbreaks, this one also originated inEastern Asia,most likely inYunnan,a province of China, where there are severalnatural plague foci.[53]The initialoutbreaksoccurred in the second half of the 18th century.[54][55]The disease remained localized inSouthwest Chinafor several years before spreading. In the city ofCanton,beginning in January 1894, the disease had killed 80,000 people by June. Daily water traffic with the nearby city ofHong Kongrapidly spread the plague there, killing over 2,400 within two months during the1894 Hong Kong plague.[56]

The third pandemic spread the disease to port cities throughout the world in the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century via shipping routes.[57]The plague infected people inChinatown in San Franciscofrom 1900 to 1904,[58]and in the nearby locales ofOaklandand theEast Bayagain from 1907 to 1909.[59]During the former outbreak, in 1902, authorities made permanent theChinese Exclusion Act,a law originally signed into existence by PresidentChester A. Arthurin 1882. The Act was supposed to last for 10 years, but was renewed in 1892 with theGeary Act,then followed by the 1902 decision. The last major outbreak in the United States occurred in Los Angeles in 1924,[60]though the disease is still present in wild rodents and can be passed to humans who come in contact with them.[35]According to theWorld Health Organization,the pandemic was considered active until 1959, when worldwide casualties dropped to 200 per year. In 1994, aplague outbreak in five Indian statescaused an estimated 700 infections (including 52 deaths) and triggered a large migration of Indians within India as they tried to avoid the disease.[citation needed]

It was during the 1894 Hong Kong plague outbreak thatAlexandre Yersinisolated the bacterium responsible (Yersinia pestis),[61]a few days after Japanese bacteriologistKitasato Shibasaburōhad isolated it.[62][63]However, the latter's description was imprecise and also expressed doubts of its relation to the disease, and thus the bacterium is today only named after Yersin.[63][64]

Society and culture

The scale of death and social upheaval associated with plague outbreaks has made the topic prominent in many historical and fictional accounts since the disease was first recognized. TheBlack Deathin particular is described and referenced innumerous contemporary sources,some of which, including works byChaucer,Boccaccio,andPetrarch,are considered part of theWestern canon.The Decameron,by Boccaccio, is notable for its use of aframe storyinvolving individuals who have fled Florence for a secluded villa to escape the Black Death. First-person, sometimes sensationalized or fictionalized, accounts of living through plague years have also been popular across centuries and cultures. For example,Samuel Pepys's diary makes several references to his first-hand experiences of theGreat Plague of Londonin 1665–66.[65]

Later works, such asAlbert Camus's novelThe PlagueorIngmar Bergman's filmThe Seventh Sealhave used bubonic plague in settings, such as quarantined cities in either medieval or modern times, as a backdrop to explore themes including the breakdown of society, institutions, and individuals during the plague; the cultural and psychologicalexistentialconfrontation with mortality; and the plague as an allegory raising contemporary moral or spiritual questions.[citation needed]

Biological warfare

Some of the earliest instances of biological warfare were said to have been products of the plague, as armies of the 14th century were recorded catapulting diseased corpses over the walls of towns and villages to spread the pestilence. This was done byJani Begwhen he attacked the city ofKaffain 1343.[66]

Later, plague was used during theSecond Sino-Japanese Waras abacteriological weaponby theImperial Japanese Army.These weapons were provided byShirō Ishii'sunitsand used in experiments on humans before being used in the field. For example, in 1940, theImperial Japanese Army Air ServicebombedNingbowith fleas carrying the bubonic plague.[67]During theKhabarovsk War Crime Trials,the accused, such as Major General Kiyoshi Kawashima, testified that, in 1941, 40 members ofUnit 731air-droppedplague-contaminated fleas onChangde.These operations caused epidemic plague outbreaks.[29]

Continued research

Substantial research has been done regarding the origin of the plague and how it traveled through the continent.[15]Mitochondrial DNAof modern rats in Western Europe indicated that these rats came from two different areas, one being Africa and the other unclear.[15]The research regarding this pandemic has greatly increased with technology.[15]Through archaeo-molecular investigation, researchers have discovered the DNA of plague bacillus in the dental core of those that fell ill to the plague.[15]Analysis of teeth of the deceased allows researchers to further understand both the demographics and mortuary patterns of the disease. For example, in 2013 in England, archeologists uncovered a burial mound to reveal 17 bodies, mainly children, who had died of the Bubonic plague. They analyzed these burial remains usingradiocarbon datingto determine they were from the 1530s, and dental core analysis revealed the presence of Yersinia pestis.[68]

Other evidence for rats that are currently still being researched consists of gnaw marks on bones, predatorpelletsand rat remains that were preserved insitu.[15]This research allows individuals to trace early rat remains to track the path traveled and in turn connect the impact of the Bubonic Plague to specific breeds of rats.[15]Burial sites, known as plague pits, offer archaeologists an opportunity to study the remains of people who died from the plague.[69]

Another research study indicates that these separate pandemics were all interconnected.[16]A current computer model indicates that the disease did not go away in between these pandemics.[16]It rather lurked within the rat population for years without causing human epidemics.[16]

See also

- List of cutaneous conditions

- List of epidemics

- Miasma theory

- Plague (disease)

- Plague doctor

- Hidradenitis suppurativa

References

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwWorld Health Organization (November 2014)."Plague Fact sheet N°267".Archivedfrom the original on 24 April 2015.Retrieved10 May2015.

- ^ab"Plague Symptoms".13 June 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2015.Retrieved21 August2015.

- ^Clinic Bp."Plague".Mayo Clinic.Archivedfrom the original on 31 May 2013.Retrieved16 June2022.

- ^abcdefPrentice MB, Rahalison L (April 2007). "Plague".Lancet.369(9568): 1196–1207.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60566-2.PMID17416264.S2CID208790222.

- ^ab"Plague Resources for Clinicians".13 June 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 21 August 2015.Retrieved21 August2015.

- ^"Plague Ecology and Transmission".13 June 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2015.Retrieved21 August2015.

- ^Edman BF, Eldridge JD (2004).Medical Entomology a Textbook on Public Health and Veterinary Problems Caused by Arthropods(Rev. ed.). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. p. 390.ISBN978-9400710092.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2023.Retrieved9 September2017.

- ^McMichael AJ (August 2010)."Paleoclimate and bubonic plague: a forewarning of future risk?".BMC Biology.8(1): 108.doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-108.PMC2929224.PMID24576348.

- ^Keyes DC (2005).Medical response to terrorism: preparedness and clinical practice.Philadelphia [u.a.]: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 74.ISBN978-0781749862.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2023.Retrieved9 September2017.

- ^Haensch S, Bianucci R, Signoli M, Rajerison M, Schultz M, Kacki S, et al. (October 2010)."Distinct clones of Yersinia pestis caused the black death".PLOS Pathogens.6(10): e1001134.doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001134.PMC2951374.PMID20949072.

- ^abc"Plague History".13 June 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 21 August 2015.Retrieved21 August2015.

- ^Cohn SK (2008)."Epidemiology of the Black Death and successive waves of plague".Medical History. Supplement.52(27): 74–100.doi:10.1017/S0025727300072100.PMC2630035.PMID18575083.

- ^LeRoux N (2007).Martin Luther As Comforter: Writings on Death Volume 133 of Studies in the History of Christian Traditions.Brill. p. 247.ISBN978-9004158801.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2023.Retrieved9 September2017.

- ^abcdeSebbane, Florent et al. "Kinetics of disease progression and host response in a rat model of bubonic plague."The American journal of pathologyvol. 166:5 (2005)

- ^abcdefghijklmMcCormick M (Summer 2003)."Rats, Communications, and Plague: Toward an Ecological History".The Journal of Interdisciplinary History.34(1): 1–25.doi:10.1162/002219503322645439.JSTOR3656705.S2CID128567627.Archivedfrom the original on 26 July 2024.Retrieved20 July2022.

- ^abcdTravis J (21 October 2000). "Model Explains Bubonic Plague's Persistence".Society for Science and the Public.

- ^ab"Symptoms of Plague".Brief Overview of Plague.iTriage. Healthagen, LLC. Archived fromthe originalon 4 February 2016.Retrieved26 November2014.

- ^Inglesby TV, Dennis DT, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, et al. (May 2000). "Plague as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense".JAMA.283(17): 2281–2290.doi:10.1001/jama.283.17.2281.PMID10807389.

- ^abcKeeling MJ, Gilligan CA (2000)."Bubonic Plague: A Metapopulation Model of a Zoonosis".Proceedings: Biological Sciences.267(1458): 2219–2230.doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1272.ISSN0962-8452.JSTOR2665900.PMC1690796.PMID11413636.

- ^abEchenberg M (2007).Plague Ports: The Global Urban Impact of Bubonic Plague, 1894–1901.New York: New York University Press. p. 9.ISBN978-0814722336.

- ^Byrne JP, ed. (2008).Encyclopedia of pestilence, pandemics, and plagues.Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. pp. 540–542.ISBN978-0-313-34101-4.OCLC226357719.Archivedfrom the original on 3 March 2020.Retrieved7 February2022.

- ^"Plague, Laboratory testing".Health Topics A to Z.Archivedfrom the original on 17 November 2010.Retrieved23 October2010.

- ^"Plague – Diagnosis and treatment – Mayo Clinic".www.mayoclinic.org.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2020.Retrieved1 December2017.

- ^Gonzalez MD, Chao T, Pettengill MA (19 September 2020)."Modern Blood Culture".Clinics in Laboratory Medicine.40(4): 379–392.doi:10.1016/j.cll.2020.07.001.PMC7501519.PMID33121610.

- ^Haynes JM (1 February 2018)."Basic Spirometry testing and interpretation for the primary care provider".Canadian Journal of Respiratory Therapy.54(4): 10.29390/cjrt–2018–017.doi:10.29390/cjrt-2018-017.PMC6516140.PMID31164790.

- ^Theilmann J, Cate F (2007). "A Plague of Plagues: The Problem of Plague Diagnosis in Medieval England".The Journal of Interdisciplinary History.37(3): 374.JSTOR4139605.

- ^Engelmann L (July 2018)."Fumigating the Hygienic Model City: Bubonic Plague and the Sulfurozador in Early-Twentieth-Century Buenos Aires".Medical History.62(3): 360–382.doi:10.1017/mdh.2018.37.PMC6113751.PMID29886876.

- ^Bertherat E, Bekhoucha S, Chougrani S, Razik F, Duchemin JB, Houti L, et al. (October 2007)."Plague reappearance in Algeria after 50 years, 2003".Emerging Infectious Diseases.13(10): 1459–1462.doi:10.3201/eid1310.070284.PMC2851531.PMID18257987.

- ^abBarenblatt D (2004).A Plague upon Humanity.pp. 220–221.

- ^"Plague".Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2010.Retrieved25 February2010.

- ^"Plague".Healthagen, LLC. Archived fromthe originalon 6 June 2011.Retrieved4 April2011.

- ^abEchenberg, Myron (2002). Pestis Redux: The Initial Years of the Third Bubonic Plague Pandemic, 1894–1901. Journal of World History, vol 13,2

- ^abFilip J (11 April 2014)."Avoiding the Black Plague Today".The Atlantic.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2020.Retrieved11 April2014.

- ^Regan M (January 2017)."Human Plague Cases Drop in the US".PBS.Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2020.Retrieved1 January2017.

- ^ab"Maps and Statistics: Plague in the United States".www.cdc.gov.23 October 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 8 April 2020.Retrieved1 December2017.

- ^"Emergencies Preparedness, Response, Plague, Madagascar, Disease Outbreak News | Plague | CDC".www.who.int.15 November 2017. Archived fromthe originalon 17 November 2017.Retrieved15 November2017.

- ^"Elmore County Child Recovering After Plague Infection"(PDF).www.cdhd.idaho.gov. 12 June 2018.Archived(PDF)from the original on 19 March 2023.Retrieved8 February2023.

- ^Schriber M, Bichell RE (7 May 2019)."Bubonic Plague Strikes in Mongolia: Why Is It Still A Threat?".NPR.Archivedfrom the original on 7 May 2019.Retrieved8 May2019.

- ^Yeung J (14 November 2019)."Two people just got the plague in China – yes, the Black Death plague".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 14 November 2019.Retrieved14 November2019.

- ^Yeung J (7 July 2020)."Chinese authorities confirm case of bubonic plague in Inner Mongolia".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2020.Retrieved6 July2020.

- ^Mathers M (14 July 2020)."Teenager dies of Black Death in Mongolia amid fears of new outbreak".The Independent.Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2020.Retrieved14 July2020.

- ^Spyrou MA, Tukhbatova RI, Wang CC, Valtueña AA, Lankapalli AK, Kondrashin VV, et al. (June 2018)."Analysis of 3800-year-old Yersinia pestis genomes suggests Bronze Age origin for bubonic plague".Nature Communications.9(1): 2234.Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.2234S.doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04550-9.PMC5993720.PMID29884871.

- ^Rasmussen S, Allentoft ME, Nielsen K, Orlando L, Sikora M, Sjögren KG, et al. (October 2015)."Early divergent strains of Yersinia pestis in Eurasia 5,000 years ago".Cell.163(3): 571–582.doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.009.PMC4644222.PMID26496604.

- ^Rascovan N, Sjögren KG, Kristiansen K, Nielsen R, Willerslev E, Desnues C, Rasmussen S (10 January 2019)."Emergence and Spread of Basal Lineages of Yersinia pestis during the Neolithic Decline".Cell.176(2): 295–305.doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.005.PMID30528431.S2CID54447284.

- ^Little LK (2007). "Life and Afterlife of the First Plague Pandemic.". In Little LK (ed.).Plague and the End of Antiquity: The Pandemic of 541–750.Cambridge University Press. pp. 8–15.ISBN978-0-521-84639-4.

- ^McCormick M (2007). "Toward a Molecular History of the Justinian Pandemic". In Little LK (ed.).Plague and the End of Antiquity: The Pandemic of 541–750.Cambridge University Press. pp. 290–312.ISBN978-0-521-84639-4.

- ^Rosen W (2007).Justinian's Flea: Plague, Empire, and the Birth of Europe.Viking Adult. p. 3.ISBN978-0-670-03855-8.Archived fromthe originalon 25 January 2010.

- ^ab"The Plague of Justinian".History Magazine.11(1). Moorshead Magazines, Limited.: 9–12 2009 – via History Reference Center.

- ^Cohn, Samuel K. (2002). "The Black Death: End of a Paradigm".American Historical Review,vol 107, 3, pp. 703–737

- ^Sean Martin (2001).Black Death: Chapter One.Harpenden, GBR: Pocket Essentials. p. 14.[ISBN missing]

- ^Spyrou MA, Musralina L, Gnecchi Ruscone GA, Kocher A, Borbone PG, Khartanovich VI, Buzhilova A, Djansugurova L, Bos KI, Kühnert D, Haak W, Slavin P, Krause J (2022)."The source of the Black Death in fourteenth-century central Eurasia".Nature.606(7915): 718–724.Bibcode:2022Natur.606..718S.doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04800-3.PMC9217749.PMID35705810.

- ^Wheelis M (2002)."Biological Warfare at the 1346 Siege of Caffa".Emerging Infectious Diseases.8(9): 971–975.doi:10.3201/eid0809.010536.PMC2732530.PMID12194776.

- ^Nicholas Wade(31 October 2010)."Europe's Plagues Came From China, Study Finds".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 4 November 2010.Retrieved1 November2010.

The great waves of plague that twice devastated Europe and changed the course of history had their origins in China, a team of medical geneticists reported Sunday, as did a third plague outbreak that struck less harmfully in the 19th century.

- ^Benedict, Carol (1996)."Bubonic plague in nineteenth-century China".Modern China.14(2). Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Univ. Press: 107–155.doi:10.1177/009770048801400201.ISBN978-0804726610.PMID11620272.S2CID220733020.

- ^Cohn SK (2003).The Black Death Transformed: Disease and Culture in Early Renaissance Europe.A Hodder Arnold. p. 336.ISBN978-0-340-70646-6.

- ^Pryor EG (1975)."The great plague of Hong Kong"(PDF).Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.15:61–70.PMID11614750.Archived(PDF)from the original on 16 January 2020.Retrieved2 June2014.

- ^"History | Plague | CDC".www.cdc.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 21 August 2015.Retrieved26 November2017.

- ^Porter D (11 September 2003). "Book Review".New England Journal of Medicine.349(11): 1098–1099.doi:10.1056/NEJM200309113491124.ISSN0028-4793.

- ^"On This Day: San Francisco Bubonic Plague Outbreak Begins".www.findingdulcinea.com.Archived fromthe originalon 1 December 2017.Retrieved25 November2017.

- ^Griggs MB."30,000 People in Quarantine After Bubonic Plague Kills One in China".Smithsonian.Archivedfrom the original on 27 July 2020.Retrieved25 November2017.

- ^Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society (2006).Plague, SARS and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong.Hong Kong University Press. pp. 35–36.ISBN978-962-209-805-3.Archivedfrom the original on 10 January 2023.Retrieved9 September2022.

- ^Pryor 1975,p. 66.

- ^abHKMSSS 2006,pp. 35–36.

- ^Solomon T (1997). "Hong Kong, 1894: the role of James A Lowson in the controversial discovery of the plague bacillus".The Lancet.350(9070). Elsevier BV: 59–62 [61–62].doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(97)01438-4.ISSN0140-6736.PMID9217728.S2CID26567729.

- ^Pepys S."Samuel Pepys Diary – Plague extracts".Samuel Pepys Diary.Archived fromthe originalon 7 April 2020.Retrieved31 August2019.

- ^"Black Death –Origin and spread of the plague in Europe".www.britannica.com.Retrieved10 October2022.

- ^"Japan triggered bubonic plague outbreak, doctor claims - Asia, World - the Independent".The Independent.Archived fromthe originalon 12 September 2011.[dead link]

- ^Pinkowski J (18 February 2020)."Black Death discovery offers rare new look at plague catastrophe".National Geographic.Archivedfrom the original on 7 May 2021.Retrieved5 December2020.

- ^Antoine D (2008)."The archaeology of" plague "".Medical History. Supplement.52(27): 101–114.doi:10.1017/S0025727300072112.PMC2632866.PMID18575084.

Further reading

- Alexander JT (2003) [First published 1980].Bubonic Plague in Early Modern Russia: Public Health and Urban Disaster.Oxford, UK; New York: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-515818-2.OCLC50253204.

- Batten-Hill D (2011).This Son of York.Kendal, England: David Batten-Hill.ISBN978-1-78176-094-9.Archived fromthe originalon 20 May 2013.Retrieved27 August2018.

- Biddle W (2002).A Field Guide to Germs(2nd Anchor Books ed.). New York: Anchor Books.ISBN978-1-4000-3051-4.OCLC50154403.

- Carol B (1996).Bubonic Plague in Nineteenth-Century China.Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.ISBN978-0-8047-2661-0.OCLC34191853.

- Kool JL (April 2005)."Risk of person-to-person transmission of pneumonic plague".Clinical Infectious Diseases.40(8): 1166–72.doi:10.1086/428617.PMID15791518.

- Little LK (2007).Plague and the End of Antiquity: The Pandemic of 541–750.New York: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-84639-4.OCLC65361042.

- Rosen W (2007).Justinian's Flea: Plague, Empire and the Birth of Europe.London: Viking Penguin.ISBN978-0-670-03855-8.

- Scott S, Duncan CJ (2001).Biology of Plagues: Evidence from Historical Populations.Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-80150-8.OCLC44811929.

External links

Works related toAn Account of the Plague at Constantinopleat Wikisource

Works related toAn Account of the Plague at Constantinopleat Wikisource