Byzantine mosaics

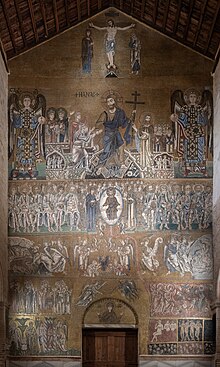

Byzantine mosaicsaremosaicsproduced from the 4th to 15th[1]centuries in and under the influence of theByzantine Empire.Mosaics were some of the most popular[2]and historically significant art forms produced in the empire, and they are still studied extensively by art historians.[3]Although Byzantine mosaics evolved out of earlierHellenisticandRomanpractices and styles,[4]craftspeople within the Byzantine Empire made important technical advances[4]and developed mosaic art into a unique and powerful form of personal and religious expression that exerted significant influence onIslamic artproduced inUmayyadandAbbasidCaliphates and theOttoman Empire.[2]

There are two main types of mosaic surviving from this period: wall mosaics in churches, and sometimes palaces, made using glasstesserae,sometimes backed bygold leaffor agold groundeffect, and floor mosaics that have mostly been found by archaeology. These often use stone pieces, and are generally less refined in creating their images. Survivals of secular wall-mosaics are few, but they show similar subject matter to floor mosaics, where many of the subjects are very similar in both churches and houses; it was not acceptable for images of sacred figures to be walked upon. Religious mosaics show similar subject matter to that found in other surviving religiousByzantine artin paintediconsand manuscript miniatures. Floor mosaics often have images of geometrical patterns, often interspersed with animals. Scenes of hunting andvenatio,arena displays where animals are killed, are popular.

Byzantine mosaics went on to influence artists in theNormanKingdom of Sicily,in theRepublic of Venice,and, carried by the spread ofOrthodox Christianity,inBulgaria,Serbia,RomaniaandRussia.[5]In the modern era, artists across the world have drawn inspiration from their focus on simplicity and symbolism, as well as their beauty.[6]

Historical context

[edit]Byzantine mosaics can trace their origin to the Greek tradition of road-building, since Greek roads were often made using small pebbles organized into patterns. By the Hellenistic Period, floor and wall art made of natural pebbles was common in both domestic and public spaces. Later, as theRoman Empireexpanded and became the dominant cultural force in the Mediterranean and Near East, Roman artists were heavily influenced by the Greek art they encountered and began installing mosaics in public buildings and private homes throughout the empire. They also added small clay or glass pieces calledtesserae,material that was also in use during the Hellenistic period. The use of tesserae enabled artists to create more colorful and finely-detailed images.[7]

In 330 AD, the emperorConstantinemoved the empire's capital from Rome toByzantium(modern-dayIstanbul), renaming itConstantinopleafter himself. Historians generally use this date for the beginning of the Byzantine Empire and divide Byzantine art into three historical periods: Early (c. 330–750), Middle (c. 850–1204) and Late (c. 1261–1453).[1]

The early period

[edit]

Constantine's conversion toChristianitylead to extensive building of Christianbasilicasin the late 4th century, in which floor, wall, and ceiling mosaics were adopted for Christian uses. The earliest examples of Christian basilicas have not survived, but the mosaics ofSanta ConstanzaandSanta Pudenziana,both from the 4th century, still exist. In another great Constantinian basilica, theChurch of the NativityinBethlehem,the original mosaic floor with typical Roman geometric motifs is partially preserved.

The reign ofJustinian Iin the 6th century coincided with the first golden age of the Byzantine Empire.[8]In 537, he completed the construction of a newpatriarchal cathedralin the capital city of Constantinople that would be the global center of the Orthodox Church: theHagia Sophia.At the time, it was the world's largest building and considered the epitome ofByzantine architecture.[9]The cathedral was decorated throughout with what were undoubtedly some of the most incredible figurative mosaics of this time period, but unfortunately these were all destroyed during theIconoclasmsthat followed. The oldest mosaics that exist today in Hagia Sophia date from the 10th through the 12th centuries, not this earlier period.[10]

AfterRome was sacked,Ravennabecame the capital of theWestern Roman Empirefrom 402 until 476, when the empire collapsed after being conquered byTheodoric the Greatand theOstrogoths.While Ravenna was under Gothic control,Arianpatrons had embarked upon a notable building program ofchapelsandbaptisteriesin Ravenna. In 535, the city was conquered byJustinian I,who created theExarchate of Ravenna,effectively making Ravenna the seat of Byzantine power on the Italian Peninsula.Orthodoxbishops under Justinian continued and expanded the construction ofbasilicasto the adjacent port city ofClasse,commissioning some of the finest mosaics anywhere in the world. Surviving monuments, some of which predate Exarchate, include theBasilica of San Vitale,theArchiepiscopal Chapel,theArian Baptistry,theNeonian Baptistry,theMausoleum of Galla Placidia,theBasilica Sant’Apollinare Nuovo,theMausoleum of Theodoricand theBasilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe.All eight of these monuments have been inscribed on theUNESCOWorld Heritagelist as superb examples of early Christian mosaic art.[11]

Although it might be the most famous, Ravenna is by no means the only place where Early Byzantine mosaics are well-preserved today. The city ofThessalonikiin Greece was the second most important city in the empire in terms of both wealth and size,[12]and like Ravenna its early Christian monuments have been designated UNESCO World Heritage sites. Masterpieces of early mosaic art in Thessaloniki include theChurch of Hosios David,theHagios Demetrios,and theRotunda.[13]

In addition, archeological discoveries in the 19th and 20th centuries unearthed manyEarly Byzantine mosaics in the Middle East,including theMadaba Mapin Jordan as well as other examples in Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine.

The Iconoclasm

[edit]

The events that mark the division between early and middle Byzantine art are called theIconoclastic Controversies,which took place from 726 to 842. This period is defined by a deep skepticism towardsicons;in fact,Emperor Leo IIIplaced an outright ban on the creation of religious images, and authorities within theOrthodox Churchencouraged the widespread destruction of religious art, including mosaics. As a result, the iconoclastic period drastically reduced the number of surviving examples of Byzantine art from the early period, especially large religious mosaics.[14]

Middle and Late Byzantine mosaics

[edit]Following the Iconoclasm, Byzantine artists were able to resume creating religious images, which people accepted not as idols to be worshiped, but as symbolic and ceremonial elements of religious ritual spaces.[5]The first part of this period, from 867 to 1056, is sometimes called theMacedonian Renaissanceand is seen as the second golden age of the Byzantine Empire.[15]Churches throughout the empire, and especially theHagia Sophiain Constantinople, were redecorated with some of the finest examples of Byzantine art ever created. For instance, the monasteries atHosios Loukas,Daphni,andNea Moni of Chioshave all been recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites,[16]and they contain some of the most magnificent Byzantine mosaics from this period.[2]

Until the disastroussack of Constantinoplein 1204 at the hands of theFourth Crusader Army,Byzantium was seen by many in Europe as the last light of civilization due to its inherited legacy of Rome and continued cultural sophistication. So during the 10th and 11th centuries, even states that were at odds with the Byzantine Empire imitated Byzantine style and sought out Greek artists to create religious mosaic cycles. For instance, the Norman KingRoger II of Sicilywas actively hostile to Byzantium, but he imported Greek craftspeople to create the mosaics forCefalù Cathedral.[5]Similarly, the earliest surviving mosaics inSt. Mark's BasilicainVenicewere probably created by artists who had left Constantinople in the mid-11th century and also worked atTorcello Cathedral.[17]

Techniques

[edit]Like other mosaics, Byzantine mosaics are made of small pieces of glass, stone, ceramic, or other material, which are calledtesserae.[18]During the Byzantine period, craftsmen expanded the materials that could be turned into tesserae, beginning to include gold leaf and precious stones, and perfected their construction. Before the tesserae could be laid, a careful foundation was prepared with multiple layers, the last of which was a fine mix of crushed lime and brick powder. On this moist surface, artists drew images and used tools like strings, compasses, and calipers to outline geometric shapes before the tesserae were carefully cemented into position to create the final image.[4]

Aesthetics

[edit]In Byzantine religious art, unlike the Classical Greek and Roman art that preceded it, symbolism became more important than realism. Instead of concentrating on making the most realistic images possible, mosaic artists of this time wanted to create idealized and sometimes exaggerated images of what existed inside the soul of a person. In addition, when used in a religious space, the overall effect created by a sea of glittering, brightly colored andgildedtesseraetook precedence over literal realism. The goal of the artist was to create an overall feeling of awe, of being in a spiritual realm,[4]or even the sense of being in the presence of God.[6]Details were not supposed to distract from the main themes.[19]

However, not all Byzantine mosaics were religious in nature. In fact, mosaic art was commonly used to decorate the floors and walls of public and private spaces with geometric patterns and secular figurative subjects.[2]

Influence and legacy

[edit]

Some Western art historians have dismissed or overlooked Byzantine art in general. For example, the deeply influential painter and historianGiorgio Vasaridefined theRenaissanceas a rejection of "that clumsy Greek style" ("quella greca goffa maniera" ).[20]However, Byzantine artists and their mosaics in particular were highly influential on the rapidly expanding Islamic decorative arts, onKeivan Rus',[5]and modern and contemporary artists across the world.[6]

Islamic artbegan in the 7th century with artists and craftsmen mostly trained in Byzantine styles, and though figurative content was greatly reduced, Byzantine decorative styles remained a great influence on Islamic art.

As Eastern Orthodox Christianity spread northward and eastward, the Byzantine empire became economically and culturally tied toKievan Rus'.In the late 10th century,Vladimir the Greatintroduced Christianitywith his own baptism and, by decree, extended it to all inhabitants of Kiev. By the 1040s, Byzantine mosaic artists were working in theHagia Sophiaat Kiev, leaving a lasting legacy not only on Russian decorative arts but also medieval painting.[5]

See also

[edit]- Byzantine architecture

- Byzantine art

- Mosaic Fragment with Man Leading a Giraffe (Art Institute of Chicago)

- Icon of Christ of Latomos

Notes

[edit]- ^ab"A beginner's guide to Byzantine Art".Khan Academy.Retrieved2019-12-26.

- ^abcd"Byzantine Mosaics".www.medievalchronicles.com.13 March 2016.Retrieved2019-12-26.

- ^Spencer, Harold (1976).Readings in Art History.Scribner's. p. 167.

- ^abcdTraverso, V. M. (2018-11-07)."The breathtaking beauty of Byzantine mosaics".Aleteia — Catholic Spirituality, Lifestyle, World News, and Culture.Retrieved2019-12-26.

- ^abcde"Byzantine Art: Characteristics, History".www.visual-arts-cork.com.Archived fromthe originalon 2016-11-20.Retrieved2019-12-27.

- ^abcKitzinger, Ernst(1977).Byzantine art in the making: main lines of stylistic development in Mediterranean art, 3rd–7th century.ISBN0-674-08956-1.OCLC70782069.

- ^"Roman Mosaics".World History Encyclopedia.Retrieved2019-12-27.

- ^Graham-Dixon, Andrew. Gregory, Mark. (2007),The art of eternity,BBC,OCLC778853051

{{citation}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Fazio, Michael W. (2009).Buildings across time: an introduction to world architecture.Moffett, Marian., Wodehouse, Lawrence. (Third ed.). Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.ISBN978-0-07-305304-2.OCLC223381546.

- ^Tutus, Sadan (2014)."10.14744/nci.2014.84803".Northern Clinics of Istanbul.1(2): 78–83.doi:10.14744/nci.2014.84803.ISSN2148-4902.PMC5175067.PMID28058307.

- ^"Early Christian Monuments of Ravenna".UNESCO World Heritage Centre.Retrieved2019-12-27.

- ^Finlay, George (2014), "The Fall of the Byzantine Empire.—A.D. 1185–1204",A History of Greece,Cambridge University Press, pp. 219–280,doi:10.1017/cbo9781139924443.003,ISBN978-1-139-92444-3

- ^"Paleochristian and Byzantine Monuments of Thessalonika".UNESCO World Heritage Centre.Retrieved2019-12-29.

- ^Sarah Brooks."Icons and Iconoclasm in Byzantium".www.metmuseum.org.Retrieved2019-12-27.

- ^Shea, Jonathan."The Macedonian Dynasty (862–1056)".Dumbarton Oaks.Retrieved2019-12-27.

- ^"Monasteries of Daphni, Hosios Loukas and Nea Moni of Chios".UNESCO World Heritage Centre.Retrieved2019-12-29.

- ^Demus, Otto. (1988).The mosaic decoration of San Marco, Venice.Kessler, Herbert L., 1941-. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.ISBN0-226-14291-4.OCLC17732671.

- ^"Learn the Ancient History of Mosaics and How to Make Your Own Colorful Creation".My Modern Met.2018-05-12.Retrieved2019-12-27.

- ^Spencer, Harold. (1983).Readings in art history.Scribner's.ISBN0-02-414390-1.OCLC810641848.

- ^"Byzantium and Italian Renaissance Art | TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities".www.torch.ox.ac.uk.Retrieved2019-12-27.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related toByzantine mosaicsat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toByzantine mosaicsat Wikimedia Commons