Pan-Celticism

Pan-Celticism(Irish:Pan-Cheilteachas,Scottish Gaelic:Pan-Cheilteachas,Breton:Pan-Keltaidd,Welsh:Pan-Geltaidd,Cornish:Pan-Keltaidh,Manx:Pan-Cheltaghys), also known asCelticismorCeltic nationalismis a political, social and cultural movement advocating solidarity and cooperation betweenCeltic nations(both theBrythonicandGaelicbranches) and themodern CeltsinNorthwestern Europe.[1]Some pan-Celtic organisations advocate the Celtic nations seceding from the United Kingdom and France and forming their own separate federal state together, while others simply advocate very close cooperation between independent sovereign Celtic nations, in the form ofBreton,Cornish,Irish,Manx,Scottish,andWelsh nationalism.

As with otherpan-nationalistmovements such aspan-Americanism,pan-Arabism,pan-Germanism,pan-Hispanism,pan-Iranism,pan-Latinism,pan-Slavism,pan-Turanianism,and others, the pan-Celtic movement grew out ofRomantic nationalismand specific to itself, theCeltic Revival.The pan-Celtic movement was most prominent during the 19th and 20th centuries (roughly 1838 until 1939). Some early pan-Celtic contacts took place through theGorseddand theEisteddfod,while the annualCeltic Congresswas initiated in 1900. Since that time theCeltic Leaguehas become the prominent face of political pan-Celticism. Initiatives largely focused on cultural Celtic cooperation, rather than explicitly politics, such as music, arts and literature festivals, are usually referred to instead asinter-Celtic.

Terminology

[edit]There is some controversy surrounding the termCelts.One such example was theCeltic League'sGalician crisis.[1]This was a debate over whether the Spanish region ofGaliciashould be admitted. The application was rejected on the basis of a lack of a presence of a Celtic language.[1]

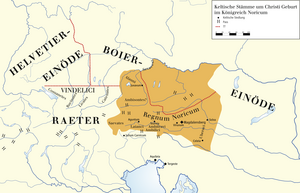

SomeAustriansclaim that they have a Celtic heritage that became Romanized under Roman rule and later Germanized after Germanic invasions.[2]Austria is the location of the first characteristically Celtic culture to exist.[2]After the annexation of Austria byNazi Germanyin 1938, in October 1940 a writer from theIrish Pressinterviewed Austrian physicistErwin Schrödingerwho spoke of Celtic heritage of Austrians, saying "I believe there is a deeper connection between us Austrians and the Celts. Names of places in the Austrian Alps are said to be of Celtic origin."[3]Contemporary Austrians express pride in having Celtic heritage and Austria possesses one of the largest collections of Celtic artefacts in Europe.[4]

Organisations such as theCeltic Congressand theCeltic Leagueuse the definition that a 'Celtic nation' is a nation with recent history of a traditional Celtic language.[1]

History

[edit]Modern conception of the Celtic peoples

[edit]

Before theRoman Empireand the rise ofChristianity,people lived in Iron Age Britain and Ireland, speaking languages from which the modernGaelic languages(includingIrish,Scottish GaelicandManx) andBrythonic languages(includingWelsh,BretonandCornish) descend. These people, along with others inContinental Europewho once spoke now extinct languages from the sameIndo-Europeanbranch (such as theGauls,CeltiberiansandGalatians), have been retroactively referred to in a collective sense as theCelts,particularly in a wide spread manner since the turn of the 18th century. Variations of the term "Celt", such asKeltoihad been used in antiquity by theGreeksand theRomansto refer to some groups of these people, such asHerodotus' use of it in regards to the Gauls.

The modern usage of "Celt" in reference to these cultures grew up gradually. A pioneer in the field wasGeorge Buchanan,a 16th-century Scottish scholar,Renaissance humanistand tutor to kingJames IV of Scotland.From aScottish Gaelic-speaking family, Buchanan in hisRerum Scoticarum Historia(1582), went over the writings ofTacituswho had discussed the similarity between the language of the Gauls and the ancient Britons. Buchanan concluded, if the Gauls wereCeltae,as they were described as in Roman sources, then the Britons wereCeltaetoo. He began to see a pattern in place names and concluded that the Britons and Irish Gaels once spoke oneCeltic languagewhich later diverged. It wouldn't be until over a century later when these ideas were widely popularised; first by the Breton scholarPaul-Yves Pezronin hisAntiquité de la Nation et de la langue celtes autrement appelez Gaulois(1703) and then by the Welsh scholarEdward Lhuydin hisArchaeologia Britannica: An Account of the Languages, Histories and Customs of the Original Inhabitants of Great Britain(1707).

By the time the modern concept of the Celts as a people had emerged, their fortunes had declined substantially, taken over byGermanic people.Firstly, theCeltic Britonsofsub-Roman Britainwere swamped by a tide ofAnglo-Saxon settlementfrom the fifth century on and lost most of their territory to them. They were subsequently referred to as theWelsh peopleand theCornish people.A group of these fled Britain altogether and settled in Continental Europe inArmorica,becoming theBreton people.TheGaelsfor a while actually expanded, pushing out of Ireland to conquer Pictland in Britain, establishingAlbaby the ninth century. From the 11th century onward, the arrival of theNormans,caused problems not only for the English but also for the Celts. The Normans invaded the Welsh kingdoms (establishing thePrincipality of Wales), theIrish kingdoms(establishing theLordship of Ireland) and took control of theScottish monarchythrough intermarrying. This advance was often done in conjunction with theCatholic Church'sGregorian Reform,which was centralising the religion in Europe.

The dawning ofearly modern Europeaffected the Celtic peoples in ways which saw what small amount of independence they had left firmly subordinated to the emergingBritish Empireand in the case of theDuchy of Brittany,theKingdom of France.Although both theKings of England(theTudors) and theKings of Scotland(theStewarts) of the day claimed Celtic ancestry and used this inArthuriancultural motifs to lay the basis for aBritish monarchy( "British" being suggested by ElizabethanJohn Dee), both dynasties promoted a centralising policy ofAnglicisation.The Gaels of Ireland lost their last kingdoms to theKingdom of Irelandafter theFlight of the Earlsin 1607, while theStatutes of Ionaattempted to de-Gaelicise the Highland Scots in 1609. The effects of these initiates were mixed, but took from the Gaels their natural leadership element, which had patronised their culture.

Under Anglocentric British rule, the Celtic-speaking peoples were reduced to a marginalised, largely poor people, small farmers and fishermen, clinging to the coast of the North Atlantic. Following theIndustrial Revolutionin the 18th century, greater multitudes were Anglicised and fled into a diaspora around the British Empire as an industrial proletariat. Further de-Gaelicisation took place for the Irish during theGreat Hungerand the Highland Scots during theHighland Clearances.Similarly for the Bretons, after theFrench Revolution,theJacobinsdemanded greater centralisation, against regional identities and forFrancization,enacted by theFrench Directoryin 1794. However,NapoleonBonaparte was greatly attracted to the romantic image of the Celt, which was partly based onJean-Jacques Rousseau's glorification of thenoble savageand the popularity ofJames Macpherson'sOssianictales throughout Europe. Bonaparte's nephew,Napoleon III,would later have theVercingétorix monumenterected to honour the Celtic Gaulish leader.[5]Indeed, in France the phrase"nos ancêtres les Gaulois"(our ancestors the Gauls) was invoked by Romantic nationalists,[5]typically in a republican fashion, to refer to the majority of the people, contrary to the aristocracy (claimed to be ofFrankish-Germanic descent).

Dawning of Pan-Celticism as a political idea

[edit]Following the dying down ofJacobitismas a political threat in Britain and Ireland, with the firm establishment ofHanoverian Britainunder the liberal, rationalist philosophy of theEnlightenment,a backlash ofRomanticismin the late 18th century occurred and "the Celt" was rehabilitated in literature, in a movement which is sometimes known as "Celtomania." The most prominent native representatives of the initial stages of thisCeltic RevivalwereJames Macpherson,author of thePoems ofOssian(1761) andIolo Morganwg,founder of theGorsedd.The imagery of the "Celtic World" also inspired English and Lowland Scots poets such asBlake,Wordsworth,Byron,ShelleyandScott.In particular theDruidsinspired fascination for outsiders, as English and French antiquarians, such asWilliam Stukeley,John Aubrey,Théophile Corret de la Tour d'AuvergneandJacques Cambry,began to associate ancientmegalithsanddolmenswith the Druids.[nb 1]

In the 1820s, early pan-Celtic contacts began to develop, firstly between the Welsh and the Bretons, asThomas PriceandJean-François Le Gonidecworked together to translate theNew Testamentinto Breton.[6]The two men were champions of their respective languages and both highly influential in their own countries. It was in this spirit that a Pan-Celtic Congress took place at theCymreigyddion y Fenni's annualEisteddfodinAbergavennyin 1838, where Bretons attended. Among these participants wasThéodore Hersart de La Villemarqué,author of the Macpherson-Morganwg influencedBarzaz Breiz,who imported theGorseddideainto Brittany.Indeed, the Breton nationalists would be the most enthusiastic pan-Celticists,[6]acting as a lynch-pin between the different parts; "trapped" within another state (France), this allowed them to draw strength from kindred peoples across the Channel and they also shared a strong attachment to theCatholic faithwith the Irish.

Across Europe, modernCeltic Studieswere developing as an academic discipline. The Germans led the way in the field with Indo-European linguistFranz Boppin 1838, followed up byJohann Kaspar Zeuss'Grammatica Celtica(1853). Indeed, as German power was growing in rivalry with France and England, the Celtic Question was of interest to them and they were able to perceive the shift towards Celtic-based nationalisms.Heinrich Zimmer,the Professor of Celtic atFriedrich Wilhelm UniversityinBerlin(predecessor ofKuno Meyer), spoke in 1899 of the powerful agitation in the "Celtic fringeof the United Kingdom's rich overcoat "and predicted that pan-Celticism would become a political force as important to the future of European politics as the much more established movements ofpan-Germanismandpan-Slavism.[7]Other academic treatments includedErnest Renan'sLa Poésie des races celtiques(1854) andMatthew Arnold'sThe Study of Celtic Literature(1867). The attention given by Arnold was a double-edged sword; he lauded Celtic poetic and musical achievements, but effeminised them and suggested they needed the cement of a sober, orderly Anglo-Saxon rule.

A concept arose among some European philologists, particularly articulated byKarl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel,whereby the "care of the national language is a sacred trust",[8]or put more simply, "no language, no nation." This dictum was also adopted by nationalists in Celtic nations, particularlyThomas Davisof theYoung Irelandmovement, who, contrary to the earlier Catholic-based "civic rights" activism of aDaniel O'Connell,asserted anIrish nationalismwhere theIrish languagewould become hegemonic once again. As he claimed a "people without a language of its own is only half a nation."[8]In a less explicitly political context, language revivalist groups emerged such as theSociety for the Preservation of the Irish Language,which would later become theGaelic League.In a Pan-Celtic context,Charles de Gaulle(uncle of the more famous GeneralCharles de Gaulle), who involved himself in Breton autonomism and advocated for a Celtic Union in 1864, argued that "so long as a conquered people speaks another language than their conquers, the best part of them remains free." De Gaulle corresponded with people in Brittany, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, arguing that each needed to cooperate in a spirit of Celtic unity and above all defend their native languages or otherwise their position as Celtic nations would be extinct. A Pan-Celtic review was founded by de Gaulle's comradeHenri Gaidozin 1873, known asRevue Celtique.

In 1867 de Gaulle organised the first ever Pan-Celtic gathering inSaint-Brieuc,Brittany. No Irish attended and the guests were mainly Welsh and Breton.[9]: 108

T. E. Ellis,the leader ofCymru Fyddwas a proponent of Pan-Celticism, stating "We must work for bringing together Celtic reformers and Celtic peoples. The interests of Irishmen, Welshmen and [Scottish] Crofters are almost identical. Their past history is very similar, their present oppressors are the same and their immediate wants are the same.[9]: 78

Pan-Celtic Congress and the Celtic Association era

[edit]The first major Pan-Celtic Congress was organised byEdmund Edward Fournier d'AlbeandBernard FitzPatrick, 2nd Baron Castletown,under the auspices of their Celtic Association and was held in August 1901 inDublin.This had followed on from an earlier sentiment of pan-Celtic feeling at theNational Eisteddfod of Wales,held in Liverpool in 1900. Another influence was Fournier's attendance atFeis Ceoilin the late 1890s, which drew musicians from the different Celtic nations. The two leaders formed somewhat of an idiosyncratic pair; Fournier, of French parentage embraced an ardentHibernophiliaand learned theIrish language,while FitzPatrick descended from ancient Irish royalty (theMac Giolla PhádraigofOsraige), but was serving in theBritish Armyand had earlier been aConservativeMP (indeed, the original Pan-Celtic Congress was delayed for a year because of theSecond Boer War).[10]The main intellectual organ of the Celtic Association wasCeltia: A Pan-Celtic Monthly Magazine,edited by Fournier, which ran from January 1901 until 1904 and was briefly revived in 1907 before finally ending for good in May 1908. Its inception was welcomed by BretonFrançois Jaffrennou.[11]An unrelated publication "The Celtic Review" was founded in 1904 and ran until 1908.[11]

Historian Justin Dolan Stover ofIdaho State Universitydescribes the movement as having "uneven successes".[11]

In total, the Celtic Association was able to organise three Pan-Celtic Congresses: Dublin (1901),Caernarfon(1904) andEdinburgh(1907). Each of these opened with an elaborateneo-druidicceremony, with the laying of theLia Cineil( "Race Stone" ), which drew inspiration from theLia FáilandStone of Scone.The stone was five foot high and consisted of five granite blocks, each with a letter of the respective Celtic nation etched into it in their own language (i.e. – "E" for Ireland, "A" for Scotland, "C" for Wales).[nb 2]At the laying of the stone, the Archdruid of the Eisteddfod,Hwfa Mônwould say three times in Gaelic, while holding a partly unsheathed sword, "Is there peace?" to which the people responded "Peace."[12]The symbolism inherent in this was meant to represent a counterpoise to theBritish Empire's assimilatingAnglo-Saxonismas articulated by the likes ofRudyard Kipling.[13]For the pan-Celts, they imagined a restored "Celtic race", but where each Celtic people would have its own national space without assimilating all into a uniformity. TheLia Cineilwas also intended as aphallic symbol,referencing the ancientmegalithshistorically associated with the Celts and overturning the "feminisation of the Celts by theirSaxonneighbours. "[13]

The response of the most advanced and militant nationalism of a "Celtic" people;Irish nationalism;was mixed. The pan-Celts were lampooned byD. P. MoraninThe Leader,under the title of "Pan-Celtic Farce."[12]The folk costumes and druidic aesthetics were especially mocked, meanwhile Moran, who associated Irish nationality with Catholicism, was suspicious of the Protestantism of both Fournier and FitzPatrick.[12]The participation of the latter as a "Tommy Atkins"against theBoers(whom Irish nationalists supported with theIrish Transvaal Brigade) was also highlighted as unsound.[12]Moran concluded that pan-Celticism was "parasitic" from Irish nationalism, created by a "foreigner" (Fournier) and sought to misdirect Irish energies.[12]Others were less polemical; opinion in theGaelic Leaguewas divided and though they elected not to send an official representative, some members did attend Congress meetings (includingDouglas Hyde,Patrick PearseandMichael Davitt).[14]More enthusiastic wasLady Gregory,who imagined an Ireland-led "Pan-Celtic Empire", whileWilliam Butler Yeatsalso attended the Dublin meeting.[14]Prominent Gaelic League activists such as Pearse,Edward Martyn,John St. Clair Boyd,Thomas William Rolleston,Thomas O'Neill Russell,Maxwell Henry CloseandWilliam Gibsonall made financial contributions to the Pan-Celtic Congress.[15]Ruaraidh Erskinewas an attendant. Erskine himself was an advocate of a "Gaelic confederation" between Ireland and Scotland.[16]

David Lloyd George,who would later to go on to be the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, delivered a speech at the 1904 Celtic Congress.[17]

Breton Regionalist UnionfounderRégis de l'Estourbeillonattended the 1907 congress, headed the Breton faction of the procession and placed the Breton stone on the Lia Cineill.Henry Jenner,Arthur William Mooreand John Crichton-Stuart, fourth Marquess of Bute likewise attended the 1907 congress.[18]

Erskine made an effort to set up a "union of Welsh, Scots and Irish with a view to action on behalf ofCeltic communism".He wrote toThomas Gwynn Jonesasking for suggestions on Welshmen to invite to London for a meeting on setting such a thing up. It is unknown if such a meeting ever took place.[19]

John de Courcy Mac Donnell founded a Celtic Union in Belgium in 1908, which organised the fourth Pan-Celtic congress as part of the1910 Brussels International Exposition.[20]Exhibitions ofhurlingwere held there and at nearby atFontenoy,commemorating theIrish Brigadeatthe 1745 battle.[21]The Celtic Union held further events up to the fifth Pan-Celtic congress 1913 in Ghent/Brussels/Namur.[20]

In Paris, 1912 the "La Ligue Celtique Francaise" was launched and had a magazine called "La Poetique" which published news and literature from all around the Celtic world.[11]

Pan-Celticism after the Easter Rising

[edit]Celtic nationalisms were boosted immensely by the IrishEaster Risingof 1916, where a group of revolutionaries belonging to theIrish Republican Brotherhoodstruck militantly against theBritish EmpireduringWorld War Ito assert anIrish Republic.Part of their political vision, building on earlier Irish-Ireland policies was a re-Gaelicisationof Ireland: that is to say ade-colonisationof Anglo cultural, linguistic and economic hegemony and a re-assertion of the native Celtic culture. After the initial rising, their politics coalesced in Ireland aroundSinn Féin.In other Celtic nations, groups were founded holding similar views and voiced solidarity with Ireland during theIrish War of Independence:this included the Breton-journalBreiz Atao,theScots National LeagueofRuaraidh Erskineand various figures in Wales who would later go on to foundPlaid Cymru.The presence ofJames Connollyand theOctober Revolutionin Russia taking place at the same time, also led some to imagine a Celticsocialismorcommunism;an idea associated with Erskine, as well as the revolutionaryJohn MacleanandWilliam Gillies.Erskine claimed the "collectivistethos in the Celtic past ", had been," undermined by Anglo-Saxon values of greed and selfishness. "

The hope of some Celtic nationalists that a semi-independent Ireland could act as a springboard forIrish Republican Army-esque equivalents for their own nations and the "liberation" of the rest of the Celtosphere would prove a disappointment. A militant Scottish volunteer force founded by Gillies,Fianna na hAlba;which like theÓglaigh na hÉireannadvocated republicanism and Gaelic nationalism; was discouraged byMichael Collinswho advised Gillies that the British state was stronger in Scotland than Ireland and that public opinion was more against them. Once theIrish Free Statewas established, the ruling parties;Fine GaelorFianna Fáil;were content to engage in inter-governmentaldiplomacywith the British state in an effort to have returned the counties in Northern Ireland, rather than supporting Celtic nationalist militants within Britain. The Irish state, particularly underÉamon de Valeradid make some effort on the cultural and linguistic front in regards to Pan-Celticism. For instance in the summer of 1947, the IrishTaoiseachde Valera visited theIsle of Manand met with Manxman,Ned Maddrell.While there he had theIrish Folklore Commissionmake recordings of the last, old, nativeManx Gaelic-speakers, including Maddrell.

Post-war initiatives and the Celtic League

[edit]

A group called "Aontacht na gCeilteach" (Celtic Unity) was set up to promote the pan-Celtic vision in November 1942. It was headed by Éamonn Mac Murchadha.MI5believed it to be a secret front for the Irish fascist partyAiltiri na hAiseirgheand was to serve as "a rallying point for Irish, Scottish, Welsh and Breton nationalists". The group had the same postal address as the party. At its foundation the group stated that "the present system is utterly repugnant to the celtic conception of life" and called for a new order based upon a "distinctive celtic philosophy". Ailtiri na hAiseirghe itself had a pan-Celtic vision and had established contacts with pro-Welsh independence political partyPlaid Cymruand Scottish independence activistWendy Wood.One day the party covered South Dublin city with posters saying "Rhyddid i Gymru" (Freedom for Wales)[22][23][24][25]Rhisiart Tal-e-bot,former President of theEuropean Free Alliance Youthis a member.[26][23][27]

The rejuvenation of Irish republicanism during the post-war period and intoThe Troubleshad some inspiration not only for other Celtic nationalists, but militant nationalists from other "small nations", such as the Basques with theETA.Indeed, this was particularly pertinent to the secessionist nationalisms of Spain, as the era ofFrancoist Spainwas coming to a close. As well as this, there was renewed interest in all things Celtic in the 1960s and 1970s. In a less militant fashion, elements withinGalician nationalismandAsturian nationalismbegan to court Pan-Celticism, attending theFestival Interceltique de Lorientand thePan Celtic FestivalatKillarney,as well as joining the International Section of the Celtic League.[28]Although this region had once been underIberian Celts,had a strong resonance in Gaelic mythology (i.e. –Breogán) and even during the Early Middle Ages had a small enclave of Celtic Briton emigrants atBritonia(similar to the case with Brittany), no Celtic language had been spoken there since the eighth century and today they speakRomance languages.[29]During the so-called "Galician crisis" of 1986,[28]the Galicians were admitted to the Celtic League as a Celtic nation (Paul Mosson had argued for their inclusion inCarnsince 1980).[28]This was subsequently overturned the following year, as the Celtic League reaffirmed the Celtic languages as the integral and defining factor in what is a Celtic nation.[30]

21st century

[edit]Following theBrexit referendumthere were calls for Pan-Celtic Unity. In November 2016, theFirst Minister of Scotland,Nicola Sturgeonstated the idea of a "Celtic Corridor" of the island of Ireland and Scotland appealed to her.[31]

In January 2019 the leader of the Welsh nationalistPlaid Cymruparty,Adam Pricespoke in favour of cooperation among the Celtic nations of Britain and Ireland following Brexit. Among his proposals were a Celtic Development Bank for joint infrastructure and investment projects in energy, transport and communications in Ireland, Wales, Scotland, and the Isle of Man, and the foundation of a Celtic union, the structure of which is already existent in theGood Friday Agreementaccording to Price. Speaking to RTÉ, the Irish national broadcaster he proposed Wales and Ireland working together to promote the indigenous languages of each nation.[32]

Blogger Owen Donavan published, on his blogState of Wales,his views on a Celtic confederation, "a voluntary union of sovereign nation-states – between Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Isle of Man would presumably be a candidate for inclusion too. Cornwall and Brittany could be added as future members if they can attain a measure of self-government." He also considered a Celtic Council, a similar co-operation that was proposed by Adam Price.[33]Journalist Jamie Dalgety has also proposed the concept of a Celtic Union involving Scotland and Ireland but suggests that lack of support for Welsh independence may mean that a Gaelic Celtic Union involving may be more appropriate.[34]Bangor University lecturer and journalist, Ifan Morgan Jones has suggested that "a short-term fix for Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland might be a greater degree of cooperation with each other, as a union within a union." he also suggested that "If they could find a way of working together in their mutual interest, that’s a fair degree of combined influence, particular if the next General Election produces a hung parliament."[35]

Anti-Celticism

[edit]A movement among some archeologists known as "Celtoscepticism" emerged from the late 1980s, through the 1990s.[36]This school of thought, initiated byJohn Collissought to undermine the basis of Celticism and cast doubts on the legitimacy of the very concept or any usage of the term "Celts". This strain of thought was particularly hostile to all butarchaeologicalevidence.[37]Partly a reaction to the rise in Celtic devolutionist tendencies, these scholars were opposed to describing theIron Agepeople of Britain as Celtic Britons and even disliked the use of the phrase Celtic in describing theCeltic languagefamily.[citation needed]Collis, an Englishman from theUniversity of Cambridge,was hostile to the methodology of German professorGustaf Kossinnaand was hostile to Celts as an ethnic identity coalescing around a concept of hereditary ancestry, culture and language (claiming this was "racist" ). Aside from this Collis was hostile to the use ofClassical literatureandIrish literatureas a source for the Iron Age period, as exemplified by Celtic scholars such asBarry Cunliffe.Throughout the duration of the debate on the historicity of the ancient Celts,John T. Kochstated that it is "the scientific fact of a Celtic family of languages that has weathered unscathed the Celtosceptic controversy."[38]

Collis was not the only figure in this field. The two other figures most prominent in the field were Malcolm Chapman with hisThe Celts: The Construction of a Myth(1992) andSimon Jamesof theUniversity of Leicesterwith hisThe Atlantic Celts: Ancient People or Modern Invention?(1999).[39]In particular, James engaged in a particularly heated exchange withVincent Megaw(and his wife Ruth) on the pages ofAntiquity.[40]The Megaws (along with others such asPeter Berresford Ellis)[41]suspected a politically motivated agenda; driven byEnglish nationalistresentment and anxiety atBritish Imperialdecline; in the whole premise of Celtosceptic theorists (such as Chapman,Nick Merrimanand J. D. Hill) and that the anti-Celtic position was a reaction to the formation of aScottish ParliamentandWelsh Assembly.For his part, James stepped forward to defend his fellow Celtosceptics, claiming that their rejection of the Celtic idea was politically motivated, but invoked "multiculturalism"and sought todeconstructthe past and imagine it as more "diverse", rather than a Celtic uniformity.[40]

Attempts to identify a distinct Celtic Race were made by the "Harvard Archaeological Mission to Ireland" in the 1930s, led byEarnest Hooton,which drew the conclusions needed by its sponsor-government. The findings were vague and did not stand up to scrutiny, and were not pursued after 1945.[42][43]The genetic studies byDavid Reichsuggest that the Celtic areas had three major population changes, and that the last group in the Iron Age, who spoke Celtic languages, had arrived in about 1000 BCE, after the building of iconic supposedly-Celtic monuments likeStonehengeandNewgrange.[44]Reich confirmed that the Indo-European root of the Celtic languages reflected a population shift, and was not just a linguistic adoption.

Manifestations

[edit]Pan-Celticism can operate on one or all of the following levels listed below:

Linguistics

[edit]Linguisticorganisations promote linguistic ties, notably theGorseddin Wales,CornwallandBrittany,and theIrish government-sponsoredColumba Initiativebetween Ireland and Scotland. Often, there is a split here between the Irish, Scots and Manx, who use Q-CelticGoidelic languages,and the Welsh, Cornish and Bretons, who speak P-CelticBrythonic languages.

Music

[edit]Our blossom is red as the life's blood we shed

For Liberty's cause against alien laws

WhenLochielandO'NeillandLlewellyndrew steel

For Alba and Erin and Cambria's weal

The flower of the free, the heather, the heather

The Bretons and Scots and Irish together

The Manx and the Welsh and Cornish forever

Six nations are we all Celtic and free!

Music is a notable aspect of Celtic cultural links. Inter-Celtic festivals have been gaining popularity, and some of the most notable include those atLorient,Killarney,Kilkenny,LetterkennyandCeltic Connectionsin Glasgow.[45][46]

Cuisine

[edit]Pan-Celtic Cuisine

[edit]Pan-Celtic cuisine, as defined by chef Colbhin MacEochaidh on thePan Celtic Cuisinewebsite refers to the culinary traditions shared among the Celtic nations, which include Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany, Cornwall, and the Isle of Man. This culinary style is characterized by a rich tapestry of flavors, incorporating local ingredients, traditional cooking methods, and cultural influences unique to each region.

Characteristics

[edit]Emphasis on Local Ingredients

[edit]Pan-Celtic cuisine places a strong emphasis on locally sourced ingredients, reflecting the diverse landscapes of the Celtic nations. Staples such as oats, seafood, dairy, root vegetables, and game meats form the foundation of many dishes.

Traditional Cooking Methods

[edit]The cuisine incorporates traditional cooking methods, including Open fire, baking, boiling, and slow-cooking. Many dishes showcase the simplicity and robustness of Celtic culinary heritage.

Common Ingredients

[edit]Commonly used ingredients in Pan-Celtic cuisine include: Oats: Oat-based dishes, such as porridge and oatcakes, are prevalent in Celtic cooking. Seafood:Given the proximity to the sea, seafood plays a prominent role, with dishes featuring fish, shellfish, and seaweed. Dairy Milk and dairy products, especially cheeses, are integral to Celtic recipes. Root Vegetables Potatoes, turnips, and carrots are often but featured prominently.

Regional Variations

[edit]Irish Cuisine

Irish cuisine is known for hearty and comforting dishes, including Irish stew, colcannon, and soda bread.

Scottish Cuisine

Scottish cuisine features dishes like haggis, neeps and tatties, and Scotch broth.

Welsh Cuisine

Welsh cuisine includes specialties such as Welsh rarebit, cawl, and bara brith.

Breton Cuisine

Breton cuisine, influenced by its coastal location, emphasizes seafood, crepes, and galettes.

Modern Interpretations

In recent years, chefs and culinary enthusiasts have reimagined Pan-Celtic cuisine, blending traditional recipes with modern techniques and global influences. This has resulted in a dynamic culinary landscape that celebrates Celtic heritage while embracing innovation.

Promotion and Awareness

[edit]Efforts to promote Pan-Celtic cuisine include culinary events, festivals, and collaborations among chefs from different Celtic regions. Additionally, online platforms and publications contribute to the dissemination of recipes and the celebration of Celtic culinary diversity.

Sports

[edit]Wrestling

[edit]There are similarities across Celtic wrestling styles, with many commentators suggesting that this indicates they stem from a common style.[47]

In the Middle Ages it is known that the "champions from the Emerald Isle (the Green Island or Ireland) met the Cornish regularly to wrestle".[47]The Irish style is known asCollar-and-elbowwrestling and uses a "jacket" as doesCornish wrestling.This was still true in the 1800s when Irish champions regularly came to London to wrestle Cornish and Devonian champions.[48][49][50][51]

Cornwall and Brittany have similar wrestling styles (Cornish wrestlingandGourenrespectively). There have been matches between wrestlers in these styles over centuries. For example, in 1551 between Cornish soldiers, involved withEdward VI's investingHenri IIwith theOrder of the Garter,and Breton "farmers".[47]There is folklore that fishing disputes between Cornish and Breton fishermen were settled with wrestling matches.[47]

More formally Inter-Celtic championships between Cornwall and Brittany started in 1928, but became less frequent since the 1980s.[47][52][53]

The Celtic wrestling championship started in 1985 comprisingGourenandScottish BackholdorCumberland and Westmorland wrestlingand sometimes other styles such asCornish wrestling.[47]

Teams that have competed in the Celtic wrestling championship include:

- Brittany

- Canaries

- Cornwall

- England

- Fryslan

- Iceland

- Ireland

- Leon

- Salzburg

- Sardinia

- Scotland

- Sweden[47]

Hurling and Shinty

[edit]Ireland and Scotland play each other athurling/shintyinternationals.[54]

Handball

[edit]As with Hurling and Shinty,Irish handballandWelsh handball(Welsh:Pêl-Law) share an ancient Celtic origin, but over the centuries they developed into two separate sports with different rules and international organisations.

Informal inter-Celtic matches were very likely a feature of industrial southern Wales in the nineteenth century, with Irish immigrant workers said to have enjoyed playing the Welsh game. However, attempts to play formal inter-Celtic matches would only begin after the formation of The Welsh Handball Association in 1987. The association was tasked with playing international matches against nations with similar sports such as Ireland, USA (American Handball) and England (Fives). To facilitate international competition, a new set of rules were devised, and even Wales' most famous Pêl-Law court (The Nelson Court) was given new markings, more in-keeping with the Irish game.[55]

Meaningful Welsh-Irish matches finally became a reality in October 1994, with "The One Wall World Championships" held in Dublin and an inaugural "European One Wall Handball Tournament" held at three courts across southern Wales the following May.[56]The 1990s were the high point for these inter-Celtic rivalries. The success of Wales' Lee Davies (World Champion in 1997) saw large crowds and high public interest. In recent years however, the decline of handball in Wales has resulted in little interest in inter-Celtic competition.[57]

Rugby

[edit]A Pan-Celtic rugby tournament had been the subject of intermittent discussions throughout the early years of professionalism. The first material steps toward a Pan-Celtic league were taken in the 1999–2000 season, when the Scottish districtsEdinburghandGlasgowwere invited to join the fully professionalWelsh Premier Division,creating theWelsh–Scottish League.In 2001, the four provinces of theIrish Rugby Football Union(IRFU) joined, with the new format being named theCeltic League.[58]

Today, the tournament is known as theUnited Rugby Championship,and has since expanded into Italy andSouth Africa,with no plans for expansion into the other Celtic nations. However, inter-Celtic rivalries continue within the league, under the legal name of the body running the competitionCeltic Rugby DAC.

InWomen's rugby union,The IRFU, WRU and SRU established the Celtic Challenge competition in 2023. While the first tournament was contested by one team from each nation (Combined Provinces XV, Welsh Developmment XV and the Thistles), it is hoped that the tournament will expand to six competing teams (two from each union) in 2024, with further expansions planned over the next 3 to 5 years.[59][60]

Political

[edit]Political groups such as theCeltic League,along withPlaid Cymruand theScottish National Partyhave co-operated at some levels in theParliament of the United Kingdom,[citation needed]and Plaid Cymru has asked questions in Parliament about Cornwall and cooperates withMebyon Kernow.TheRegional Council of Brittany,the governing body of theRegion of Brittany,has developed formal cultural links with the WelshSeneddand there are fact-finding missions. Political pan-Celticism can be taken to include everything from a full federation of independent Celtic states, to occasional political visits. Duringthe Troubles,theProvisional IRAadopted a policy of not mounting attacks in Scotland and Wales, as they viewed England alone as the colonial force occupying Ireland.[61]This was also possibly influenced by the IRA chief of staffSeán Mac Stíofáin(John Stephenson), a London-born republican with pan-Celtic views.[61]

In 2023 a 'Celtic Forum' took place in Brittany. Attendees included First Minister of WalesMark Drakeford,Deputy First Minister of Scotland,Shona Robinson,Leader of theCornwall Council,Linda Taylor, Republic of Ireland Ambassador to France, Niall Burgess andLoïg Chesnais-Girard,the President of theRegional Council of Brittany.Political representatives fromAsturiasandGaliciawere also present. Drakeford described the forum as "an excellent opportunity to come together as Celtic nations and regions, to build on our cultural and historical links and seek out areas for future collaboration, such as marine energy."[62]

Town twinnings

[edit]Town twinningis common between Wales – Brittany and Ireland – Brittany, covering hundreds of communities, with exchanges of local politicians, choirs, dancers and school groups.[63]

Historical connections

[edit]The kingdom ofDál Riatawas aGaelicoverkingdom on the western seaboard of Scotland with some territory on the northern coasts of Ireland. In the late sixth and early seventh century it encompassed roughly what is nowArgyll and ButeandLochaberin Scotland and alsoCounty Antrimin Northern Ireland.[64]

As recently as the 13th century, "members of the Scottish elite were still proud to proclaim their Gaelic-Irish origins and identified Ireland as the homeland of the Scots."[65]The 14th century Scottish KingRobert the Bruceasserted a common identity for Ireland and Scotland.[65]However, in later medieval times, Irish and Scottish interests diverged for a number of reasons, and the two peoples grew estranged.[66]The conversion of the Scots toProtestantismwas one factor.[66]The stronger political position of Scotland in relation to England was another.[66]The disparate economic fortunes of the two was a third reason; by the 1840s Scotland was one of the richest areas in the world and Ireland one of the poorest.[66]

Over the centuries there was considerable migration between Ireland and Scotland, primarily as ScotsProtestantstook part in theplantation of Ulsterin the 17th century and then later, as many Irish began to be evicted from their homes, some emigrating to Scottish cities in the 19th century to escape the "Irish famine".Recently the field of Irish-Scottish studies has developed considerably, with the Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative (ISAI) founded in 1995. To date, three international conferences have been held in Ireland and Scotland, in 1997, 2000 and 2002.[67]

Organisations

[edit]- The International Celtic Congress is a non-political cultural organisation that promotes the Celtic language in the six nations of Ireland, Scotland, Brittany, Wales, Isle of Man and Cornwall.

- TheCeltic League,is a Pan-Celtic political organization.

Celtic regions/countries

[edit]

A number of Europeans from the central and western regions of the continent have some Celtic ancestry. As such it is generally claimed that the 'litmus test' of Celticism is a surviving Celtic language[1]and it was on this criterion that the Celtic league rejectedGalicia.The following regions have a surviving Celtic language and it on this criterion that they are considered, by The Pan Celtic Congress in 1904 andCeltic League,to be theCeltic nations.[1][68]

Other regions with Celtic heritage are:

- Austria[2]– Within the famousHallstatt culturalregion – possible home of the Celts.

- Czech Republic – Home of the Boii (Boiohaemum –Bohemia)

- England[69]

- Faroe Islands

- France – Known previously, in classical times, as Gallia/Gaul. Classical writings on Gaul and its native Celtic tribes are the most extensive literature we have from the time.

- Northern Italy, known asCisalpine Gaul,was inhabited by populations of Celtic lineage.

- Portugal – Home to theLusitani,Gallaecian,Turdetaniand other Celtic tribes.

- Spain – A large portion of the Iberian peninsula was inhabited by Celtic tribes. Spain and Portugal has been hypothesized as the place of origin of the Celts by Professor John Koch, of theUniversity of Wales.[70]

- Asturias[1][71]– the principality of Asturias was named after theAsturCeltic tribe.

- Cantabria– The current autonomous community (former duchy) was named after theCantabritribe.

- Galicia[1](withNorth Portugal[71]) – together as Gallaecia

- Castile and León

- Castilla–La Mancha

- Extremadura

- Community of Madrid

- Andalusia(Turdetaniand other tribes)

- SloveniaHistorical part of Celtic Kingdom of Noricum

Celts outside Europe

[edit]Areas with a Celtic language speaking population

[edit]There are notableIrishandScottish Gaelicspeaking enclaves inAtlantic Canada.[72]

ThePatagoniaregion of Argentina has a sizeable Welsh speaking population. The Welsh settlement in Argentina started in 1865 and is known asY Wladfa.

The Celtic diaspora

[edit]The Celticdiasporain theAmericas,as well as New Zealand and Australia, is significant and organised enough that there are numerous organisations, cultural festivals and university-level language classes available in major cities throughout these regions.[73]In the United States,Celtic Family Magazineis a nationally distributed publication providing news, art, and history on Celtic people and their descendants.[74]

The IrishGaelic gamesofGaelic footballandhurlingare played across the world and are organised by theGaelic Athletic Associationwhile the Scottish gameshintyhas seen recent growth in theUnited States.[75]

Timeline of Pan-Celticism

[edit]J.T. Koch observes that modern Pan-Celticism arose in the contest of European romantic pan-nationalism, and like other pan-nationist movements, flourished mainly before the First World War.[76]He sees twentieth century efforts in this regard as possibly arising out of a post-modern search for identity in the face of increased industrialization, urbanization and technology.

- 1820: The Royal Celtic Society founded in Scotland[77]

- 1838: First Celtic Congress calledPan-Celtic Congress,Abergavenny[78]

- 1867: Second Celtic Congress,Saint-Brieuc[79]

- 1888: Pan-Celtic Society formed inDublin[80]

- 1891:Pan-Celtic Society disbands[80]

- 1919–1922:Irish War of Independence,five-sixths of Ireland becomes independent, Northern Ireland gets devolved government

- 1939–1945:Second World Warand German occupation of Brittany

- 1947: Celtic Union formed[81]

- 1950: Collapse of Celtic Union[81]

- 1950: Cornwall hosts its first Celtic congress[82]

- 1961: ModernCeltic Leaguefounded atRhosllanerchrugog[83]

- 1971: KillarneyPan Celtic Festivalbegins[84]

- 1997:Columba Initiativebegins[85]

- 1999:Scottish Parliament[86]andWelsh Assembly[87]open

- 2000: TheCornish Constitutional Conventionis formed[88]

- 2000–2001:TheCornish Constitutional Conventioncollect over 50,000 signatures endorsing the call for aCornish Assembly.[88]

See also

[edit]- List of movements in Wales

- Agnes O'Farrelly

- Alan Heusaff

- Armes Prydein

- Charles de Gaulle

- John Stuart Stuart-Glennie

- Mona Douglas

- Richard Jenkin

- Ruaraidh Erskine

- Sophia Morrison

- Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué

Notes

[edit]- ^The current ofneo-Druidism,deriving from the writings of the likes of William Stukeley and Iolo Morganwag, had its origins more in the milieu offreemasonrythan any lineal connection to the ancient Celtic Druids and their culture, which survived latest in the Gaelic world with thefilíandseanchaí(existing alongside Christianity). Thus neo-paganism had a very limited appeal to most people in Celtic nations, instead being largely English and Welsh based. English-based quasi-masonic groups such as theAncient Order of Druidsprovided the inspiration for Iolo'sGorsedd.Later masonic groups and writers such asGodfrey Higginsand thenRobert Wentworth Little's Ancient and Archaeological Order of Druids, were English founded or based.

- ^Due to the all-but-extinction of theCornish language,the movement ofCornish nationalismwould not be included within the Pan-Celtic Congress until 1904, afterHenry JennerandL. C. R. Duncombe-Jewellof the Cornish Celtic Society made their argument to the Celtic Association. Cornwall ( "K" ) was subsequently added to theLia Cineiland the Cornish have been recognised as the sixth Celtic nation ever since.

References

[edit]- ^abcdefghEllis, Peter Berresford (2002).Celtic dawn: the dream of Celtic unity.Y Lolfa.ISBN9780862436438.Retrieved19 January2010.

- ^abcCarl Waldman, Catherine Mason.Encyclopedia of European Peoples.Infobase Publishing, 2006. P. 42.

- ^Walter J. Moore.Schrödinger: Life and Thought.Cambridge, England, UK: Press Syndicate of Cambridge University Press, 1989. p.373.

- ^Kevin Duffy. Who Were the Celts? Barnes & Noble Publishing, 1996. P. 20.

- ^abFenn 2001,p. 65.

- ^abHaywood 2014,p. 190.

- ^O'Donnell 2008,p. 134.

- ^abMotherway 2016,p. 87.

- ^abDe Barra, Caoimhín (2018).The Coming of the Celts, AD 1860: Celtic Nationalism in Ireland and Wales.Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.ISBN9780268103378.

- ^Platt 2011,p. 61.

- ^abcdStover, Justin Dolan (2012). "Modern Celtic Nationalism in the Period of the Great War: Establishing Transnational Connections".Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium.32:286–301.JSTOR23630944.

- ^abcdePlatt 2011,p. 62.

- ^abPlatt 2011,p. 64.

- ^abPlatt 2011,p. 63.

- ^De Barra, Caoimhín (30 March 2018).The Coming of the Celts, AD 1862: Celtic Nationalism in Ireland and Wales.University of Notre Dame Press. p. 198.ISBN9780268103408.

- ^"Connections across the North Channel: Ruaraidh Erskine and Irish Influence in Scottish Discontent, 1906-1920".17 April 2013.

- ^"Celts divided by more than the Irish Sea".The Irish Times.

- ^"Meriden Morning Record – Google News Archive Search".

- ^De Barra 2018p. 295

- ^ab

- O'Leary, Philip (1986). ""Children of the Same Mother": Gaelic Relations with the Other Celtic Revival Movements 1882–1916 ".Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium.6:106.ISSN1545-0155.JSTOR20557176.

- "Union Celtique"(PDF).The Pan-Celtic Quarterly(1). Brussels: Union Celtique: 7–8. 1911.Retrieved4 February2024.

- "Chronique: XIII [Congrės pan-celtique à Gand]".Révue Celtique(in French).34.Paris: Honoré Champion: 353. 1913.

- ^Smith, Raymond (1966).Decades of Glory: A Comprehensive History of the National Game.Little & McClean. p. 78.

- ^Architects of Resurrection: Ailtiri na hAiserighe and the fascist 'new order' in Ireland by R. M. Douglas (pg 271)

- ^abPittock, Murray (1999).Celtic Identity and the British Image.Manchester University Press.ISBN9780719058264.

- ^"Resurgence".1966.

- ^Williams, Derek R. (1 July 2014).Following 'An Gof': Leonard Truran, Cornish Activist and Publisher.The Cornovia Press.ISBN9781908878113.

- ^Ó Luain, Cathal (13 October 2008)."Celtic League: General Secretary in Udb Interview".Agence Bretagne Presse.

- ^Robert William White (2006).Ruairí Ó Brádaigh: The Life and Politics of an Irish Revolutionary.Indiana University Press.ISBN978-0253347084.

- ^abcBerresford Ellis 2002,p. 27.

- ^Berresford Ellis 2002,p. 26.

- ^Berresford Ellis 2002,p. 28.

- ^"Scottish first minister backs calls for 'Celtic corridor'".Irish Independent.29 November 2016.

- ^Nualláin, Irene Ní (10 January 2019)."Welsh party leader calls for Celtic political union".RTÉ.ie.

- ^"Could a Celtic Union work?".State of Wales.11 March 2019.Retrieved12 June2022.

- ^says, Austen Lynch (25 September 2021)."Thought Experiment: A Celtic Union".The Glasgow Guardian.Retrieved12 June2022.

- ^"Might a 'Celtic union' be one route to shifting the balance of power within the UK?".Nation.Cymru.12 June 2022.Retrieved12 June2022.

- ^Hood, Laura (13 July 2015)."How being Celtic got a bad name – and why you should care".The Conversation.Retrieved24 November2017.

- ^"Celtoscepticism, a convenient excuse for ignoring non-archaeological evidence?".Raimund Karl.Retrieved24 November2017.

- ^Williams, Daniel G. (2009). "Another lost cause? Pan-Celticism, race and language".Irish Studies Review.17:89–101.doi:10.1080/09670880802658174.S2CID143640161.

- ^"The Rise and Fall of the 'C' word (Celts)".Heritage Daily.Retrieved24 November2017.

- ^ab"The academic debate on the meaning of 'Celticness'".University of Leicester.Archived fromthe originalon 25 May 2017.Retrieved24 November2017.

- ^"Historical notes: Did the ancient Celts really exist?".The Independent.London. 5 January 1999.Archivedfrom the original on 24 May 2022.Retrieved24 November2017.

- ^Carew M.The Quest for the Irish Celt – The Harvard Archaeological Mission to Ireland, 1932-1936.Irish Academic Press, 2018

- ^"Skulls, a Nazi director and the quest for the 'true' Celt".Irish Independent.29 April 2018.

- ^Reich D.Who we are and how we got here;Oxford UP 2018, pp.114-121.

- ^"ALTERNATIVE MUSIC PRESS-Celtic music for a" New World Paradigm "".Retrieved2 January2010.

- ^"Scottish Music Festivals-Great Gatherings of Artists".Archived fromthe originalon 25 February 2010.Retrieved2 January2010.

- ^abcdefgGuy Jaouen and Matthew Bennett Nicols:Celtic Wrestling, The Jacket Styles,Fédération Internationale des Luttes Associées (Switzerland) 2007, p1-183.

- ^Wrestling,Globe, 25 September 1826, p3.

- ^Wrestling,Weekly Dispatch (London), 23 November 1828, p5.

- ^Egan, Pierce:Book of Sport, No XXI The Wrestlers,T T & J Tegg, 1832, p321-336.

- ^Wrestling,Morning Advertiser, 30 May 1849, p3.

- ^Historic Event – Bretons hosted at Cornish Gorsedd,Western Mail, 27 August 1929, p6.

- ^Wrestling in Brittany: How the Cornishmen Fared,Cornish Guardian' 30 August 1928, p14.

- ^"BBC – A Sporting Nation – The first combined shinty/hurling match 1897".BBC.

- ^Moore, Joe (December 1996)."The Handball Court at Nelson".The Green Dragon.1(1).

- ^Hughes, Tony."The 1995 European One Wall Handball Championships".fivesonline.net.

- ^Jenkins, James O."Pêl-law".A Fine Beginning.

- ^"Y Gynghrair Geltaidd"(in Welsh). BBC Chwaraeon. 28 September 2005.Retrieved8 August2011.

- ^"Scottish Rugby, IRFU & WRU have created a pilot Celtic Challenge competition, supported by World Rugby, to provide a high-performance tournament window ahead of the 2023 TikTok Six Nations Championship".Scottish Rugby.21 December 2022.Retrieved25 March2023.

- ^"Combined Provinces XV to Compete in Women's Celtic Challenge Tournament".Ulster Rugby.Retrieved25 March2023.

- ^abPittock, Murray.Celtic Identity and the British Image.Manchester University Press,1999.p. 111

- ^Evans, Tomos."What is the Celtic Forum and why are leaders meeting in Brittany?".Sky News.

- ^"Home page of Cardiff Council – Cardiff's twin cities".Cardiff Council. 15 June 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 9 June 2011.Retrieved10 August2010.

- ^Oxford Companion to Scottish History p. 161 162, edited by Michael Lynch, Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-923482-0.

- ^ab"Making the Caledonian Connection: The Development of Irish and Scottish Studies." by T.M. Devine. Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen. inRadharc: A Journal of Irish StudiesVol 3: 2002 pg 4. The article in turn cites "Myth and Identity in Early Medieval Scotland" by E.J. Cowan,Scottish Historical Review,xxii (1984) pgs 111–135.

- ^abcd"Making the Caledonian Connection: The Development of Irish and Scottish Studies." by T.M. Devine. Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen. inRadharc: A Journal of Irish StudiesVol 3: 2002 pgs 4–8

- ^Devine, T.M. "Making the Caledonian Connection: The Development of Irish and Scottish Studies." Radharc Journal of Irish Studies. New York. Vol 3, 2002.

- ^"The Celtic League".celticleague.net.

- ^"We're nearly all Celts under the skin".The Scotsman.21 September 2006.

- ^Koch, John (5 March 2013)."Tartessian, Europe's newest and oldest Celtic language".History Ireland.Retrieved20 August2020.

- ^ab"National Geographic map of celtic regions".Archived fromthe originalon 7 March 2008.Retrieved20 January2010.

- ^Ó Broin, Brian (2011)."An Analysis of the Irish-Speaking Communities of North America: Who are they, what are their opinions, and what are their needs?".Retrieved31 March2012– via Academia.edu.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^"Modern Irish Linguistics".University of Sydney. Archived fromthe originalon 29 October 2013.Retrieved19 May2012.

- ^"The Welsh in America".Wales Arts Review.Retrieved28 April2014.

- ^"Thursday's Scottish gossip".BBC News. 20 August 2009.Retrieved20 January2010.

- ^Celtic Culture: A-Celti.ABC-CLIO. 20 August 2006.ISBN9781851094400– via Google Books.

- ^"The Royal Celtic Society".Archived fromthe originalon 2 March 2016.Retrieved5 February2010.

- ^"Celtic Congresses in other countries".Retrieved5 February2010.

- ^"The International Celtic Congress Resolutions and Themes".Retrieved5 February2010.

- ^abHughes, J. B. (1953). "The Pan-Celtic Society".The Irish Monthly.81(953): 15–38.JSTOR20516479.

- ^ab"The Capital Scot".Archived fromthe originalon 8 January 2011.Retrieved5 February2010.

- ^"A short history of the Celtic Congress".Archived fromthe originalon 25 July 2011.Retrieved5 February2010.

- ^"Rhosllanerchrugog".Archived fromthe originalon 1 January 2011.Retrieved5 February2010.

- ^"Welcome to the 2010 Pan Celtic Festival".Retrieved5 February2010.

- ^"Columba Initiative".16 December 1997. Archived fromthe originalon 25 January 2012.Retrieved5 February2010.

- ^"Scottish Parliament".Retrieved5 February2010.

- ^"Queen and Welsh Assembly".Retrieved5 February2010.

- ^ab"Campaign for a Cornish assembly".Retrieved5 February2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bailyn, Bernard (2012).Strangers Within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British Empire.UNC Press Books.ISBN978-0807839416.

- Berresford Ellis, Peter (1985).The Celtic Revolution: Study in Anti-Imperialism.Y Lolfa Cyf.ISBN978-0862430962.

- Berresford Ellis, Peter (2002).Celtic Dawn: The Dream of Celtic Unity.Y Lolfa Cyf.ISBN978-0862436438.

- Carruthers, Gerard (2003).English Romanticism and the Celtic World.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-1139435949.

- Collins, Kevin (2008).Catholic Churchmen and the Celtic Revival in Ireland, 1848-1916.Four Courts Press.ISBN978-1851826582.

- Fenn, Richard K (2001).Beyond Idols: The Shape of a Secular Society.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0198032854.

- Hechter, Michael (1975).Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development, 1536-1966.Routledge.ISBN978-0710079886.

- Dudley Edwards, Owen (1968).Celtic Nationalism.Routledge.ISBN978-0710062536.

- Gaskill, Howard (2008).The Reception of Ossian in Europe.A&C Black.ISBN978-1847146007.

- Haywood, John (2014).The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age.Routledge.ISBN978-1317870166.

- Jensen, Lotte (2016).The Roots of Nationalism: National Identity Formation in Early Modern Europe, 1600-1815.Amsterdam University Press.ISBN978-9048530649.

- Motherway, Susan (2016).The Globalization of Irish Traditional Song Performance.Routledge.ISBN978-1317030041.

- O'Donnell, Ruán (2008).The Impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations.Irish Academic Press.ISBN978-0716529651.

- O'Driscoll, Robert (1985).The Celtic Consciousness.George Braziller.ISBN978-0807611364.

- O'Rahilly, Cecile (1924).Ireland and Wales: Their Historical and Literary Relations.Longman's.

- Ortenberg, Veronica (2006).In Search of the Holy Grail: The Quest for the Middle Ages.A&B Black.ISBN978-1852853839.

- Pittock, Murray G. H. (1999).Celtic Identity and the British Image.Manchester University Press.ISBN978-0719058264.

- Pittock, Murray G. H. (2001).Scottish Nationality.Palgrave Macmillan.ISBN978-1137257246.

- Platt, Len (2011).Modernism and Race.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-1139500258.

- Tanner, Marcus (2006).The Last of the Celts.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0300115352.

- Loffler, Marion (2000).A Book of Mad Celts: John Wickens and the Celtic Congress of Caernaroon 1904.Gomer Press.ISBN978-1859028964.