Cervix

| Cervix | |

|---|---|

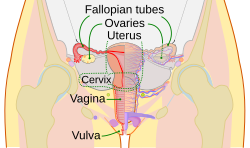

Human cervix | |

Diagram of the female human reproductive tract | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Paramesonephric ducts |

| Artery | Vaginal arteryanduterine artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cervix uteri |

| MeSH | D002584 |

| TA98 | A09.1.03.010 |

| TA2 | 3508 |

| FMA | 17740 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Thecervix(pl.:cervices) orcervix uteriis a dynamic fibromuscularsexual organof the femalereproductive systemthat connects thevaginawith theuterine cavity.[1]The human female cervix has been documented anatomically since at least the time ofHippocrates,over 2,000 years ago.[citation needed]The cervix is approximately 4 cm long with a diameter of approximately 3 cm and tends to be described as a cylindrical shape, although the front and back walls of the cervix are contiguous.[1]The size of the cervix changes throughout a woman's life cycle. For example, during the fertile years of a woman'sreproductive cycle,females tend to have a larger cervixvis á vispostmenopausalfemales; likewise, females who have producedoffspringhave a larger sized cervix than females who have not produced offspring.[1]

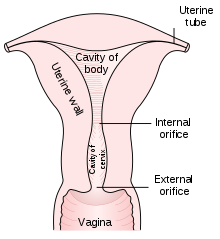

In relation to the vagina, the part of the cervix that opens to the uterus is called theinternal osand the opening of the cervix in the vagina is called theexternal os,[1]while between is the conduit of the cervix, commonly referred to as thecervical canal.The lower part of the cervix, known as the vaginal portion of the cervix (or ectocervix), bulges into the top of the vagina.[citation needed]The endocervix borders the uterus. The cervical canal has at least two types ofepithelia(lining): the endocervical lining is glandular epithelium that lines the endocervix with a singlelayer of column-shaped cells;while the ectocervical part of the conduit contains squamous epithelium.[1]Squamous epithelium line the conduit withmultiple layers of cells topped with flat cells.These two linings converge at thesquamocolumnar junction(SCJ). This junction changes location dynamically throughout a woman's life.[1]

Cervical infections with thehuman papillomavirus(HPV) can cause changes in the epithelium, which can lead tocancer of the cervix.Cervical cytologytests can detect cervical cancer and its precursors, and enable early successful treatment. Ways to avoid HPV include avoiding heterosexual sex, utilising penile condoms, and receiving theHPV vaccination.HPV vaccines, developed in the early 21st century, reduce the risk of developing cervical cancer by preventing infections from the main cancer-causing strains of HPV.[2]

The conduit of the cervix is the organ that allows for blood to flow from a woman'suterusand out through hervaginaatmenstruation,which releases when a woman's uterus dislodges from her womb every month of her fertile years, unless the mechanics through which anegg cellpermitssperm cellstofertilizeit.

Several methods ofcontraceptionaim to prevent fertilization by blocking this conduit, includingcervical capsandcervical diaphragms,preventing the passage of sperm through the cervix. Other approaches aiming to prevent contraception include methods that observe cervical mucus, such as theCreighton ModelandBillings method.Cervical mucus changes in consistency throughout women'smenstrual periods,which may signalovulation.

During vaginalchildbirth,the cervix must flatten anddilateto allow thefoetusto progress along the birth canal. Midwives and doctors use the extent of thedilation of the cervixto assist decision-making during childbirth.

Structure

[edit]

The cervix is part of thefemale reproductive system.Around 2–3 centimetres (0.8–1.2 in) in length,[3]it is the lower narrower part of the uterus continuous above with the broader upper part—or body—of the uterus.[4]The lower end of the cervix bulges through the anterior wall of the vagina, and is referred to as the vaginal portion of cervix (or ectocervix) while the rest of the cervix above the vagina is called thesupravaginal portion of cervix.[4]A central canal, known as thecervical canal,runs along its length and connects thecavity of the body of the uteruswith the lumen of the vagina.[4]The openings are known as theinternal osandexternal orifice of the uterus(or external os), respectively.[4]The mucosa lining the cervical canal is known as theendocervix,[5]and the mucosa covering the ectocervix is known as the exocervix.[6]The cervix has an inner mucosal layer, a thick layer ofsmooth muscle,and posteriorly the supravaginal portion has aserosalcovering consisting of connective tissue and overlyingperitoneum.[4]

In front of the upper part of the cervix lies thebladder,separated from it by cellular connective tissue known asparametrium,which also extends over the sides of the cervix.[4]To the rear, the supravaginal cervix is covered by peritoneum, which runs onto the back of the vaginal wall and then turns upwards and onto therectum,forming therecto-uterine pouch.[4]The cervix is more tightly connected to surrounding structures than the rest of the uterus.[7]

The cervical canal varies greatly in length and width between women or over the course of a woman's life,[3]and it can measure 8 mm (0.3 inch) at its widest diameter inpremenopausaladults.[8]It is wider in the middle and narrower at each end. The anterior and posterior walls of the canal each have a vertical fold, from which ridges run diagonally upwards and laterally. These are known aspalmate folds,due to their resemblance to a palm leaf. The anterior and posterior ridges are arranged in such a way that they interlock with each other and close the canal. They are often effaced after pregnancy.[7]

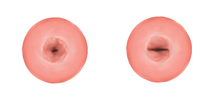

The ectocervix (also known as the vaginal portion of the cervix) has a convex, elliptical shape and projects into the cervix between the anterior and posteriorvaginal fornices.On the rounded part of the ectocervix is a small, depressedexternal opening,connecting the cervix with the vagina. The size and shape of the ectocervix and the external opening (external os) can vary according to age, hormonal state, and whetherchildbirthhas taken place. In women who have not had a vaginal delivery, the external opening is small and circular, and in women who have had a vaginal delivery, it is slit-like.[8]On average, the ectocervix is 3 cm (1.2 in) long and 2.5 cm (1 in) wide.[3]

Blood is supplied to the cervix by the descending branch of theuterine artery[9]and drains into theuterine vein.[10]Thepelvic splanchnic nerves,emerging asS2–S3,transmit the sensation of pain from the cervix to the brain.[5]These nerves travel along theuterosacral ligaments,which pass from the uterus to the anteriorsacrum.[9]

Three channels facilitatelymphatic drainagefrom the cervix.[11]The anterior and lateral cervix drains tonodesalong the uterine arteries, travelling along thecardinal ligamentsat the base of thebroad ligamentto theexternal iliac lymph nodesand ultimately theparaaortic lymph nodes.The posterior and lateral cervix drains along the uterine arteries to theinternal iliac lymph nodesand ultimately theparaaortic lymph nodes,and the posterior section of the cervix drains to the obturator and presacrallymph nodes.[3][10][11]However, there are variations as lymphatic drainage from the cervix travels to different sets of pelvic nodes in some people. This has implications in scanning nodes for involvement in cervical cancer.[11]

Aftermenstruationand directly under the influence ofestrogen,the cervix undergoes a series of changes in position and texture. During most of the menstrual cycle, the cervix remains firm, and is positioned low and closed. However, asovulationapproaches, the cervix becomes softer and rises to open in response to the higher levels of estrogen present.[12]These changes are also accompanied by changes in cervical mucus,[13]described below.

Development

[edit]As a component of the femalereproductive system,the cervix is derived from the twoparamesonephric ducts(also called Müllerian ducts), which develop around the sixth week ofembryogenesis.During development, the outer parts of the two ducts fuse, forming a singleurogenitalcanal that will become thevagina,cervix anduterus.[14]The cervix grows in size at a smaller rate than the body of the uterus, so the relative size of the cervix over time decreases, decreasing from being much larger than the body of the uterus infetal life,twice as large during childhood, and decreasing to its adult size, smaller than the uterus, after puberty.[10]Previously, it was thought that during fetal development, the original squamous epithelium of the cervix is derived from theurogenital sinusand the original columnar epithelium is derived from the paramesonephric duct. The point at which these two original epithelia meet is called the original squamocolumnar junction.[15]: 15–16 New studies show, however, that all the cervical as well as large part of thevaginal epitheliumare derived from Müllerian duct tissue and that phenotypic differences might be due to other causes.[16]

Histology

[edit]

The endocervical mucosa is about 3 mm (0.12 in) thick and lined with a single layer of columnar mucous cells. It contains numerous tubular mucous glands, which empty viscous alkaline mucus into the lumen.[4]In contrast, the ectocervix is covered with nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium,[4]which resembles the squamous epithelium lining the vagina.[17]: 41 The junction between these two types of epithelia is called the squamocolumnar junction.[17]: 408–11 Underlying both types of epithelium is a tough layer ofcollagen.[18]The mucosa of the endocervix is not shed during menstruation. The cervix has more fibrous tissue, including collagen andelastin,than the rest of the uterus.[4]

-

The squamocolumnar junction of the cervix, with abrupt transition: The ectocervix, with its stratified squamous epithelium, is visible on the left. Simple columnar epithelium, typical of the endocervix, is visible on the right. A layer ofconnective tissueis visible under both types of epithelium.

-

Transformation zone types:[19]

Type 1: Completely ectocervical (common under hormonal influence).

Type 2: Endocervical component but fully visible (common before puberty).

Type 3: Endocervical component, not fully visible (common after menopause).

Inprepubertalgirls, the functional squamocolumnar junction is present just within the cervical canal.[17]: 411 Upon entering puberty, due to hormonal influence, and during pregnancy, the columnar epithelium extends outward over the ectocervix as the cervix everts.[15]: 106 Hence, this also causes the squamocolumnar junction to move outwards onto the vaginal portion of the cervix, where it is exposed to the acidic vaginal environment.[15]: 106 [17]: 411 The exposed columnar epithelium can undergo physiologicalmetaplasiaand change to tougher metaplastic squamous epithelium in days or weeks,[17]: 25 which is very similar to the original squamous epithelium when mature.[17]: 411 The new squamocolumnar junction is therefore internal to the original squamocolumnar junction, and the zone of unstable epithelium between the two junctions is called thetransformation zoneof the cervix.[17]: 411 Histologically, the transformation zone is generally defined as surface squamous epithelium with surface columnar epithelium or stromal glands/crypts, or both.[20]

After menopause, the uterine structures involute and the functional squamocolumnar junction moves into the cervical canal.[17]: 41

Nabothian cysts(or Nabothian follicles) form in the transformation zone where the lining of metaplastic epithelium has replaced mucous epithelium and caused a strangulation of the outlet of some of the mucous glands.[17]: 410–411 A buildup of mucus in the glands forms Nabothian cysts, usually less than about 5 mm (0.20 in) in diameter,[4]which are considered physiological rather than pathological.[17]: 411 Both gland openings and Nabothian cysts are helpful to identify the transformation zone.[15]: 106

Function

[edit]Fertility

[edit]The cervical canal is a pathway through which sperm enter the uterus after being induced byestradiolafterpenile-vaginal intercourse,[21]and some forms ofartificial insemination.[22]Some sperm remains in cervical crypts, infoldings of the endocervix, which act as a reservoir, releasing sperm over several hours and maximising the chances of fertilisation.[23]A theory states the cervical and uterine contractions duringorgasmdraw semen into the uterus.[21]Although the "upsuck theory" has been generally accepted for some years, it has been disputed due to lack of evidence, small sample size, and methodological errors.[24][25]

Some methods offertility awareness,such as theCreighton modeland theBillings methodinvolve estimating a woman's periods of fertility and infertility by observing physiological changes in her body[citation needed].Among these changes are several involving the quality of her cervical mucus: the sensation it causes at thevulva,its elasticity (Spinnbarkeit), its transparency, and the presence offerning.[12]

Cervical mucus

[edit]Several hundred glands in the endocervix produce 20–60 mg of cervicalmucusa day, increasing to 600 mg around the time of ovulation. It is viscous because it contains large proteins known asmucins.The viscosity and water content varies during themenstrual cycle;mucus is composed of around 93% water, reaching 98% at midcycle. These changes allow it to function either as a barrier or a transport medium to spermatozoa. It contains electrolytes such as calcium, sodium, and potassium; organic components such as glucose, amino acids, and soluble proteins; trace elements including zinc, copper, iron, manganese, and selenium; free fatty acids; enzymes such asamylase;andprostaglandins.[13]Its consistency is determined by the influence of the hormones estrogen and progesterone. At midcycle around the time ofovulation—a period of high estrogen levels— the mucus is thin and serous to allow sperm to enter the uterus and is more alkaline and hence more hospitable to sperm.[23]It is also higher in electrolytes, which results in the "ferning" pattern that can be observed in drying mucus under low magnification; as the mucus dries, the salts crystallize, resembling the leaves of a fern.[12]The mucus has a stretchy character described asSpinnbarkeitmost prominent around the time of ovulation.[26]

At other times in the cycle, the mucus is thick and more acidic due to the effects of progesterone.[23]This "infertile" mucus acts as a barrier to keep sperm from entering the uterus.[27]Women taking anoral contraceptive pillalso have thick mucus from the effects of progesterone.[23]Thick mucus also preventspathogensfrom interfering with a nascent pregnancy.[28]

Acervical mucus plug,called the operculum, forms inside the cervical canal during pregnancy. This provides a protective seal for the uterus against the entry of pathogens and against leakage of uterine fluids. The mucus plug is also known to have antibacterial properties. This plug is released as the cervix dilates, either during the first stage of childbirth or shortly before.[29]It is visible as a blood-tinged mucous discharge.[30]

Childbirth

[edit]

The cervix plays a major role inchildbirth.As thefetusdescends within the uterus in preparation for birth, thepresenting part,usuallythe head,rests on and is supported by the cervix.[31]As labour progresses, the cervix becomes softer and shorter, begins to dilate, and withdraws to face the anterior of the body.[32]The support the cervix provides to the fetal head starts to give way when the uterus begins itscontractions.During childbirth, thecervix must dilateto a diameter of more than 10 cm (3.9 in) to accommodate the head of the fetus as it descends from the uterus to the vagina. In becoming wider, the cervix also becomes shorter, a phenomenon known aseffacement.[31]

Along with other factors, midwives and doctors use the extent ofcervical dilationto assist decision making duringchildbirth.[33][34]Generally, the active first stage of labour, when the uterine contractions become strong and regular,[33]begins when the cervical dilation is more than 3–5 cm (1.2–2.0 in).[35][36]The second phase of labor begins when the cervix has dilated to 10 cm (4 in), which is regarded as its fullest dilation,[31]and is when active pushing and contractions push the baby along thebirth canalleading to the birth of the baby.[34]The number of past vaginal deliveriesis a strong factor in influencing how rapidly the cervix is able to dilate in labour.[31]The time taken for the cervix to dilate and efface is one factor used in reporting systems such as theBishop score,used to recommend whether interventions such as aforceps delivery,induction,orCaesarean sectionshould be used in childbirth.[31]

Cervical incompetenceis a condition in which shortening of the cervix due to dilation and thinning occurs, before term pregnancy. Short cervical length is the strongest predictor ofpreterm birth.[32]

Contraception

[edit]Several methods ofcontraceptioninvolve the cervix.Cervical diaphragmsare reusable, firm-rimmed plastic devices inserted by a woman prior to intercourse that cover the cervix. Pressure against the walls of the vagina maintain the position of the diaphragm, and it acts as a physical barrier to prevent the entry of sperm into the uterus, preventingfertilisation.Cervical capsare a similar method, although they are smaller and adhere to the cervix by suction. Diaphragms and caps are often used in conjunction withspermicides.[37]In one year, 12% of women using the diaphragm will undergo an unintended pregnancy, and with optimal use this falls to 6%.[38]Efficacy rates are lower for the cap, with 18% of women undergoing an unintended pregnancy, and 10–13% with optimal use.[39]Most types ofprogestogen-only pillsare effective as a contraceptive because they thicken cervical mucus, making it difficult for sperm to pass along the cervical canal.[40]In addition, they may also sometimes prevent ovulation.[40]In contrast, contraceptive pills that contain both oestrogen and progesterone, thecombined oral contraceptive pills,work mainly by preventingovulation.[41]They also thicken cervical mucus and thin the lining of the uterus, enhancing their effectiveness.[41]

Clinical significance

[edit]Cancer

[edit]In 2008, cervical cancer was the third-most common cancer in women worldwide, with rates varying geographically from less than one to more than 50 cases per 100,000 women.[needs update][42]It is a leading cause of cancer-related death in poor countries, where delayed diagnosis leading to poor outcomes is common.[43]The introduction of routine screening has resulted in fewer cases of (and deaths from) cervical cancer, however this has mainly taken place in developed countries. Most developing countries have limited or no screening, and 85% of the global burden occurring there.[44]

Cervical cancer nearly always involves human papillomavirus (HPV) infection.[45][46]HPV is a virus with numerous strains, several of which predispose to precancerous changes in the cervical epithelium, particularly in the transformation zone, which is the most common area for cervical cancer to start.[47]HPV vaccines,such asGardasilandCervarix,reduce the incidence of cervical cancer, by inoculating against the viral strains involved in cancer development.[48]

Potentially precancerous changes in the cervix can be detected bycervical screening,using methods including aPap smear(also called a cervical smear), in whichepithelialcells are scraped from the surface of the cervix andexamined under a microscope.[48]Thecolposcope,an instrument used to see a magnified view of the cervix, was invented in 1925. The Pap smear was developed byGeorgios Papanikolaouin 1928.[49]ALEEP procedureusing a heated loop ofplatinumto excise a patch of cervical tissue was developed byAurel Babesin 1927.[50]In some parts of the developed world including the UK, the Pap test has been superseded withliquid-based cytology.[51]

An inexpensive, cost-effective and practical alternative in poorer countries isvisual inspection with acetic acid(VIA).[43]Instituting and sustaining cytology-based programs in these regions can be difficult, due to the need for trained personnel, equipment and facilities and difficulties in follow-up. With VIA, results and treatment can be available on the same day. As a screening test, VIA is comparable to cervical cytology in accurately identifying precancerous lesions.[52]

A result ofdysplasiais usually further investigated, such as by taking acone biopsy,which may also remove the cancerous lesion.[48]Cervical intraepithelial neoplasiais a possible result of the biopsy and represents dysplastic changes that may eventually progress to invasive cancer.[53]Most cases of cervical cancer are detected in this way, without having caused any symptoms. When symptoms occur, they may include vaginal bleeding, discharge, or discomfort.[54]

Inflammation

[edit]Inflammation of the cervix is referred to ascervicitis.This inflammation may be of the endocervix or ectocervix.[55]When associated with the endocervix, it is associated with a mucous vaginal discharge andsexually transmitted infectionssuch aschlamydiaandgonorrhoea.[56]As many as half of pregnant women having a gonorrheal infection of the cervix are asymptomatic.[57]Other causes include overgrowth of thecommensal floraof the vagina.[46]When associated with the ectocervix, inflammation may be caused by theherpes simplexvirus. Inflammation is often investigated through directly visualising the cervix using aspeculum,which may appear whiteish due to exudate, and by taking a Pap smear and examining for causal bacteria. Special tests may be used to identify particular bacteria. If the inflammation is due to a bacterium, then antibiotics may be given as treatment.[56]

Anatomical abnormalities

[edit]Cervical stenosisis an abnormally narrow cervical canal, typically associated with trauma caused by removal of tissue for investigation or treatment of cancer, orcervical canceritself.[46][58]Diethylstilbestrol,used from 1938 to 1971 to prevent preterm labour and miscarriage, is also strongly associated with the development of cervical stenosis and other abnormalities in the daughters of the exposed women. Other abnormalities include:vaginal adenosis,in which the squamous epithelium of the ectocervix becomes columnar; cancers such asclear cell adenocarcinomas;cervical ridges and hoods; and development of a cockscomb cervix appearance,[59]which is the condition wherein, as the name suggests, the cervix of theuterusis shaped like acockscomb.About one third of women born todiethylstilbestrol-treated mothers (i.e. in-utero exposure) develop a cockscomb cervix.[59]

Enlarged folds or ridges of cervicalstroma(fibrous tissues) andepitheliumconstitute a cockscomb cervix.[60]Similarly, cockscombpolypslining the cervix are usually considered or grouped into the same overarching description. It is in and of itself considered abenignabnormality; its presence, however is usually indicative of DES exposure, and as such women who experience these abnormalities should be aware of their increased risk of associated pathologies.[61][62][63]

Cervical agenesisis a rare congenital condition in which the cervix completely fails to develop, often associated with the concurrent failure of the vagina to develop.[64]Other congenital cervical abnormalities exist, often associated with abnormalities of the vagina anduterus.The cervix may be duplicated in situations such asbicornuate uterusanduterine didelphys.[65]

Cervical polyps,which are benign overgrowths of endocervical tissue, if present, may cause bleeding, or a benign overgrowth may be present in the cervical canal.[46]Cervical ectropionrefers to the horizontal overgrowth of the endocervical columnar lining in a one-cell-thick layer over the ectocervix.[56]

Other animals

[edit]Female marsupials havepaired uteri and cervices.[66][67]Mosteutherian(placental) mammal species have a single cervix and a single, bipartite or bicornuate uterus.Lagomorphs,rodents, aardvarks and hyraxes have a duplex uterus and two cervices.[68]Lagomorphs and rodents share many morphological characteristics and are grouped together in the cladeGlires.Anteaters of the familyMyrmecophagidaeare unusual in that they lack a defined cervix; they are thought to have lost the characteristic rather than other mammals developing a cervix on more than one lineage.[69]Indomestic pigs,the cervix contains a series of five interdigitating pads that hold the boar's corkscrew-shaped penis during copulation.[70]

Etymology and pronunciation

[edit]The wordcervix(/ˈsɜːrvɪks/) came to English from theLatincervīx,where it means "neck", and like its Germanic counterpart, it can refer not only to theneck[of the body] but also to an analogous narrowed part of an object. The cervix uteri (neck of the uterus) is thus the uterine cervix, but in English the wordcervixused alone usually refers to it. Thus the adjectivecervicalmay refer either to the neck (as incervical vertebraeorcervical lymph nodes) or to the uterine cervix (as incervical caporcervical cancer).

Latincervixcame from theProto-Indo-Europeanrootker-,referring to a "structure that projects". Thus, the word cervix is linguistically related to theEnglishword "horn",thePersianword for "head" (Persian:سرsar), the Greek word for "head" (Greek:κορυφήkoruphe), and the Welsh and Romanian words for "deer" (Welsh:carw,Romanian:cerb).[71][72]

The cervix was documented in anatomical literature in at least the time ofHippocrates;cervical cancer was first described more than 2,000 years ago, with descriptions provided by bothHippocratesandAretaeus.[49]However, there was some variation inword senseamong early writers, who used the term to refer to both the cervix and the internal uterine orifice.[73]The first attested use of the word to refer to the cervix of the uterus was in 1702.[71]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^abcdefPrendiville, Walter; Sankaranarayanan, Rengaswamy (2017),"Anatomy of the uterine cervix and the transformation zone",Colposcopy and Treatment of Cervical Precancer,International Agency for Research on Cancer,retrieved2024-03-29

- ^"Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines".National Cancer Institute.Bethesda, MD. 29 December 2011.Retrieved18 June2014.

- ^abcdKurman RJ, ed. (1994).Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract(4th ed.). New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 185–201.ISBN978-1-4757-3889-6.

- ^abcdefghijkGray H(1995). Williams PL (ed.).Gray's Anatomy(38th ed.).Churchill Livingstone.pp. 1870–73.ISBN0-443-04560-7.

- ^abDrake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AW (2005).Gray's Anatomy for Students.Illustrations by Richardson P, Tibbitts R. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. pp. 415, 423.ISBN978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ^Ovalle WK, Nahirney PC (2013). "Female Reproductive System".Netter's Essential Histology.Illustrations by Frank H. Netter, contributing illustrators, Joe Chovan, et al. (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 416.ISBN978-1-4557-0631-0.

- ^abGardner E, Gray DJ, O'Rahilly R (1969) [1960].Anatomy: A Regional Study of Human Structure(3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders. pp. 495–98.

- ^abKurman RJ, ed. (2002).Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract(5th ed.). Springer. p. 207.

- ^abDaftary SN, Chakravari S (2011).Manual of Obstretics, 3/e.Elsevier. pp. 1–16.ISBN978-81-312-2556-1.

- ^abcEllis H (2011). "Anatomy of the uterus".Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine.12(3): 99–101.doi:10.1016/j.mpaic.2010.11.005.

- ^abcMould TA, Chow C (2005). "The Vascular, Neural and Lymphatic Anatomy of the Cervix". In Jordan JA, Singer A (eds.).The Cervix(2nd ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. pp.41–47.ISBN9781405131377.

- ^abcWeschler T (2006).Taking charge of your fertility: the definitive guide to natural birth control, pregnancy achievement, and reproductive health(Revised ed.). New York, NY: Collins. pp.59, 64.ISBN978-0-06-088190-0.

- ^abSharif K, Olufowobi O (2006). "The structure chemistry and physics of human cervical mucus". In Jordan J, Singer A, Jones H, Shafi M (eds.).The Cervix(2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp.157–68.ISBN978-1-4051-3137-7.

- ^Schoenwolf GC, Bleyl SB, Brauer PR, Francis-West PH (2009). ""Development of the Urogenital system"".Larsen's human embryology(4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier.ISBN978-0-443-06811-9.

- ^abcdMcLean JM (November 2006). "Morphogenesis and Differentiation of the cervicovaginal epithelium". In Jordan J, Singer A, Jones H, Shafi M (eds.).The Cervix(2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.ISBN978-1-4051-3137-7.

- ^Reich O, Fritsch H (October 2014). "The developmental origin of cervical and vaginal epithelium and their clinical consequences: a systematic review".Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease.18(4): 358–360.doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000023.PMID24977630.S2CID3060493.

- ^abcdefghijBeckmann CR, Herbert W, Laube D, Ling F, Smith R (March 2013).Obstetrics and Gynecology(7th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 408–11.ISBN9781451144314.

- ^Young B (2006).Wheater's functional histology: a text and colour atlas(5th ed.). Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p.376.ISBN978-0-443-06850-8.

- ^International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy (IFCPC) classification. References:

-"Transformation zone (TZ) and cervical excision types".Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia.

-Jordan J, Arbyn M, Martin-Hirsch P, Schenck U, Baldauf JJ, Da Silva D, et al. (December 2008)."European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening: recommendations for clinical management of abnormal cervical cytology, part 1".Cytopathology.19(6): 342–354.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2303.2008.00623.x.PMID19040546.S2CID16462929. - ^Mukonoweshuro P, Oriowolo A, Smith M (June 2005)."Audit of the histological definition of cervical transformation zone".Journal of Clinical Pathology.58(6): 671.PMC1770692.PMID15917428.

- ^abGuyton AC, Hall JE (2005).Textbook of Medical Physiology(11th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders. p. 1027.ISBN978-0-7216-0240-0.

- ^"Demystifying IUI, ICI, IVI and IVF".Seattle Sperm Bank. 4 January 2014.Retrieved9 November2014.

- ^abcdBrannigan RE, Lipshultz LI (2008)."Sperm Transport and Capacitation".The Global Library of Women's Medicine.doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10316.

- ^Levin RJ (November 2011). "The human female orgasm: a critical evaluation of its proposed reproductive functions".Sexual and Relationship Therapy.26(4): 301–14.doi:10.1080/14681994.2011.649692.S2CID143550619.

- ^Borrow AP, Cameron NM (March 2012). "The role of oxytocin in mating and pregnancy".Hormones and Behavior.61(3): 266–276.doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.11.001.PMID22107910.S2CID45783934.

- ^Anderson M, Karasz A, Friedland S (November 2004)."Are vaginal symptoms ever normal? a review of the literature".MedGenMed.6(4): 49.PMC1480553.PMID15775876.

- ^Westinore A, Billings E (1998).The Billings Method: Controlling Fertility Without Drugs or Devices.Toronto, ON: Life Cycle Books. p. 37.ISBN0-919225-17-9.

- ^Wagner G, Levin RJ (September 1980)."Electrolytes in vaginal fluid during the menstrual cycle of coitally active and inactive women".Journal of Reproduction and Fertility.60(1): 17–27.doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0600017.PMID7431318.

- ^Becher N, Adams Waldorf K, Hein M, Uldbjerg N (May 2009). "The cervical mucus plug: structured review of the literature".Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.88(5): 502–513.doi:10.1080/00016340902852898.PMID19330570.S2CID23738950.

- ^Lowdermilk DL, Perry SE (2006).Maternity Nursing(7th ed.). Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Elsevier Mosby. p.394.ISBN978-0-323-03366-4.

- ^abcdeCunningham F, Leveno K, Bloom S, Hauth J, Gilstrap L, Wenstrom K (2005).Williams obstetrics(22nd ed.). New York; Toronto: McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 157–60, 537–39.ISBN0-07-141315-4.

- ^abGoldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R (January 2008)."Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth".Lancet.371(9606): 75–84.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4.PMC7134569.PMID18177778.

- ^abNICE (2007). Section 1.6,Normal labour: first stage

- ^abNICE (2007). Section 1.7,Normal labour: second stage

- ^ACOG(2012)."Obstetric Data Definitions Issues and Rationale for Change"(PDF).Revitalize.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 November 2013.Retrieved4 November2014.

- ^Su M, Hannah WJ, Willan A, Ross S, Hannah ME (October 2004). "Planned caesarean section decreases the risk of adverse perinatal outcome due to both labour and delivery complications in the Term Breech Trial".BJOG.111(10): 1065–1074.doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00266.x.PMID15383108.S2CID10086313.

- ^NSW Family Planning (2009).Contraception: healthy choices: a contraceptive clinic in a book(2nd ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: UNSW Press. pp. 27–37.ISBN978-1-74223-136-5.

- ^Trussell J (May 2011)."Contraceptive failure in the United States".Contraception.83(5): 397–404.doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021.PMC3638209.PMID21477680.

- ^Trussell J, Strickler J, Vaughan B (May–Jun 1993). "Contraceptive efficacy of the diaphragm, the sponge and the cervical cap".Family Planning Perspectives.25(3): 100–5, 135.doi:10.2307/2136156.JSTOR2136156.PMID8354373.

- ^abYour Guide to the progesterone-one pill(PDF).Family Planning Association (UK). pp. 3–4.ISBN978-1-908249-53-1.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2014-03-27.Retrieved9 November2014.

- ^abYour Guide to the combined pill(PDF).Family Planning Association (UK). January 2014. p. 4.ISBN978-1-908249-50-0.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2013-11-02.Retrieved9 November2014.

- ^Arbyn M, Castellsagué X, de Sanjosé S, Bruni L, Saraiya M, Bray F, Ferlay J (December 2011)."Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008".Annals of Oncology.22(12): 2675–2686.doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr015.PMID21471563.

- ^abWorld Health Organization(February 2014)."Fact sheet No. 297: Cancer".Retrieved23 July2014.

- ^Vaccarella S, Lortet-Tieulent J, Plummer M, Franceschi S, Bray F (October 2013). "Worldwide trends in cervical cancer incidence: impact of screening against changes in disease risk factors".European Journal of Cancer.49(15): 3262–3273.doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2013.04.024.PMID23751569.

- ^Wahl CE (2007).Hardcore pathology.Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 72.ISBN9781405104982.

- ^abcdMitchell RS, Kumar V, Robbins SL, Abbas AK, Fausto N (2007).Robbins basic pathology(8th ed.). Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 716–21.ISBN978-1-4160-2973-1.

- ^Lowe A, Stevens JS (2005).Human histology(3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA; Toronto, ON: Elsevier Mosby. pp. 350–51.ISBN0-323-03663-5.

- ^abcFauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. (2008).Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine(17th ed.). New York [etc.]: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp.608–09.ISBN978-0-07-147692-8.

- ^abGasparini R, Panatto D (May 2009). "Cervical cancer: from Hippocrates through Rigoni-Stern to zur Hausen".Vaccine.27(Suppl 1): A4–A5.doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.069.PMID19480961.

- ^Diamantis A, Magiorkinis E, Androutsos G (November 2010). "Different strokes: Pap-test and Babes method are not one and the same".Diagnostic Cytopathology.38(11): 857–859.doi:10.1002/dc.21347.PMID20973044.S2CID823546.

- ^Gray W, Kocjan G, eds. (2010).Diagnostic Cytopathology.Churchill Livingstone. p. 613.ISBN9780702048951.

- ^Sherris J, Wittet S, Kleine A, Sellors J, Luciani S, Sankaranarayanan R, Barone MA (September 2009)."Evidence-based, alternative cervical cancer screening approaches in low-resource settings".International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health.35(3): 147–154.doi:10.1363/3514709.PMID19805020.

- ^Cannistra SA, Niloff JM (April 1996). "Cancer of the uterine cervix".The New England Journal of Medicine.334(16): 1030–1038.doi:10.1056/NEJM199604183341606.PMID8598842.

- ^Colledge NR, Walker BR, Ralston SH, eds. (2010).Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine.Illustrated by Britton R (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p.276.ISBN978-0-7020-3084-0.

- ^Stamm W (2013).The Practitioner's Handbook for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Diseases.Seattle STD/HIV Prevention Training Center. pp. Chapter 7: Cervicitis. Archived fromthe originalon 2013-06-22.

- ^abcFauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. (2008).Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine(17th ed.). New York [etc.]: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp.828–29.ISBN978-0-07-147692-8.

- ^Kenner C (2014).Comprehensive neonatal nursing care(5th ed.). New York: Springer Publishing Company, LLC.ISBN9780826109750.Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh.

- ^Valle RF, Sankpal R, Marlow JL, Cohen L (2002). "Cervical Stenosis: A Challenging Clinical Entity".Journal of Gynecologic Surgery.18(4): 129–43.doi:10.1089/104240602762555939.

- ^abCasey PM, Long ME, Marnach ML (February 2011)."Abnormal cervical appearance: what to do, when to worry?".Mayo Clinic Proceedings.86(2): 147–50, quiz 151.doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0512.PMC3031439.PMID21270291.

- ^"Diethylstilbestrol (DES) Cervix".National Cancer Institute Visuals.National Cancer Institute.Retrieved14 May2015.

- ^Wingfield M (June 1991)."The daughters of stilboestrol".BMJ.302(6790): 1414–1415.doi:10.1136/bmj.302.6790.1414.PMC1670127.PMID2070103.

- ^Mittendorf R (June 1995). "Teratogen update: carcinogenesis and teratogenesis associated with exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero".Teratology.51(6): 435–445.doi:10.1002/tera.1420510609.PMID7502243.

- ^Herbst AL, Poskanzer DC, Robboy SJ, Friedlander L, Scully RE (February 1975). "Prenatal exposure to stilbestrol. A prospective comparison of exposed female offspring with unexposed controls".The New England Journal of Medicine.292(7): 334–339.doi:10.1056/NEJM197502132920704.PMID1117962.

- ^Fujimoto VY, Miller JH, Klein NA, Soules MR (December 1997). "Congenital cervical atresia: report of seven cases and review of the literature".American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.177(6): 1419–1425.doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70085-1.PMID9423745.

- ^Patton PE, Novy MJ, Lee DM, Hickok LR (June 2004). "The diagnosis and reproductive outcome after surgical treatment of the complete septate uterus, duplicated cervix and vaginal septum".American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.190(6): 1669–75, discussion p.1675–78.doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.046.PMID15284765.

- ^Tyndale-Biscoe CH (2005).Life of Marsupials.Csiro Publishing.ISBN978-0-643-06257-3.

- ^Tyndale-Biscoe H, Renfree M (30 January 1987).Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-33792-2.

- ^Feldhamer GA, Drickamer LC, Vessey SH, Merritt JF, Krajewski C (2007).Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, Ecology.Baltimore, MD: JHU Press. p. 198.ISBN9780801886959.

- ^Novacek MJ, Wyss AR (September 1986). "Higher-Level Relationships of the Recent Eutherian Orders: Morphological Evidence".Cladistics.2(4): 257–287.doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1986.tb00463.x.PMID34949071.S2CID85140444.

- ^"The Female - Swine Reproduction".livestocktrail.illinois.edu.Archived fromthe originalon 2022-02-10.Retrieved2017-03-07.

- ^abHarper D."Cervix".Etymology Online.Retrieved19 March2014.

- ^Harper D."Horn".Etymology Online.Retrieved19 March2014.

- ^Galen IJ, ed. (2011).Galen: On Diseases and Symptoms.Translated by Johnston I. Cambridge University Press. p. 247.ISBN978-1-139-46084-2.

Cited texts

[edit]- "Intrapartum care: Care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth".NICE.September 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 2014-04-26.

External links

[edit] Media related toCervix uteriat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toCervix uteriat Wikimedia Commons

![Transformation zone types:[19] Type 1: Completely ectocervical (common under hormonal influence). Type 2: Endocervical component but fully visible (common before puberty). Type 3: Endocervical component, not fully visible (common after menopause).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Transformation_zone_types.png/430px-Transformation_zone_types.png)