Chemical compound

Achemical compoundis achemical substancecomposed of many identicalmolecules(ormolecular entities) containingatomsfrom more than onechemical elementheld together bychemical bonds.Amolecule consisting of atoms of only one elementis therefore not a compound. A compound can be transformed into a different substance by achemical reaction,which may involve interactions with other substances. In this process, bonds between atoms may be broken and/or new bonds formed.

There are four major types of compounds, distinguished by how the constituent atoms are bonded together.Molecular compoundsare held together bycovalent bonds;ionic compoundsare held together byionic bonds;intermetallic compoundsare held together bymetallic bonds;coordination complexesare held together bycoordinate covalent bonds.Non-stoichiometric compoundsform a disputed marginal case.

Achemical formulaspecifies the number of atoms of each element in a compound molecule, using the standardchemical symbolswith numericalsubscripts.Many chemical compounds have a uniqueCAS numberidentifier assigned by theChemical Abstracts Service.Globally, more than 350,000 chemical compounds (including mixtures of chemicals) have been registered for production and use.[1]

History of the concept

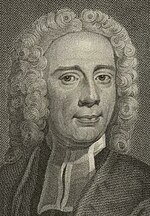

Robert Boyle

The term "compound" —with a meaning similar to the modern—has been used at least since 1661 whenRobert Boyle'sThe Sceptical Chymistwas published. In this book, Boyle variously used the terms "compound",[2]"compounded body",[3]"perfectly mixt body",[4]and "concrete".[5]"Perfectly mixt bodies" included for example gold,[4]lead,[4]mercury,[2]and wine.[6]While the distinction between compound andmixtureis not so clear, the distinction betweenelementand compound is a central theme.

Quicksilver... withAqua fortiswill be brought into a... white Powder... with Sulphur it will compose a blood-red and volatile Cinaber. And yet out of all these exotick Compounds, we may recover the very same running Mercury.[7]

Corpuscles of elements and compounds

Boyle used the concept of "corpuscles" —or "atomes",[8]as he also called them—to explain how a limited number of elements could combine into a vast number of compounds:

If we assigne to the Corpuscles, whereof each Element consists, a peculiar size and shape... such... Corpuscles may be mingled in such various Proportions, and... connected so many... wayes, that an almost incredible number of... Concretes may be compos’d of them.[5]

Isaac Watts

In hisLogick,published in 1724, the English minister and logicianIsaac Wattsgave an early definition of chemical element, and contrasted element with chemical compound in clear, modern terms.[9]

Among Substances, some are called Simple, some are Compound... Simple Substances... are usually called Elements, of which all other Bodies are compounded: Elements are such Substances as cannot be resolved, or reduced, into two or more Substances of different Kinds.... Followers of Aristotle made Fire, Air, Earth and Water to be the four Elements, of which all earthly Things were compounded; and they suppos'd the Heavens to be a Quintessence, or fifth sort of Body, distinct from all these: But, since experimental Philosophy... have been better understood, this Doctrine has been abundantly refuted. The Chymists make Spirit, Salt, Sulphur, Water and Earth to be their five Elements, because they can reduce all terrestrial Things to these five: This seems to come nearer the Truth; tho' they are not all agreed... Compound Substances are made up of two or more simple Substances... So a Needle is simple Body, being made only of Steel; but a Sword or a Knife is a compound because its... Handle is made of Materials different from the Blade.

Definitions

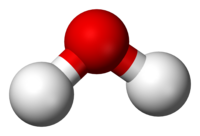

Any substance consisting of two or more different types ofatoms(chemical elements) in a fixedstoichiometricproportion can be termed achemical compound;the concept is most readily understood when considering purechemical substances.[10]: 15 [11][12]It follows from their being composed of fixed proportions of two or more types of atoms that chemical compounds can be converted, viachemical reaction,into compounds or substances each having fewer atoms.[13]Achemical formulais a way of expressing information about the proportions of atoms that constitute a particular chemical compound, usingchemical symbolsfor the chemical elements, andsubscriptsto indicate the number of atoms involved. For example,wateris composed of twohydrogen atomsbonded to oneoxygenatom: the chemical formula is H2O. In the case ofnon-stoichiometric compounds,the proportions may be reproducible with regard to their preparation, and give fixed proportions of their component elements, but proportions that are not integral [e.g., forpalladium hydride,PdHx(0.02 < x < 0.58)].[14]

Chemical compounds have a unique and definedchemical structureheld together in a defined spatial arrangement bychemical bonds.Chemical compounds can bemolecularcompounds held together bycovalent bonds,saltsheld together byionic bonds,intermetallic compoundsheld together bymetallic bonds,or the subset ofchemical complexesthat are held together bycoordinate covalent bonds.[15]Purechemical elementsare generally not considered chemical compounds, failing the two or more atom requirement, though they often consist of molecules composed of multiple atoms (such as in thediatomic moleculeH2,or thepolyatomic moleculeS8,etc.).[15]Manychemicalcompounds have a unique numerical identifier assigned by theChemical Abstracts Service(CAS): itsCAS number.

There is varying and sometimes inconsistent nomenclature differentiating substances, which include truly non-stoichiometric examples, from chemical compounds, which require the fixed ratios. Many solid chemical substances—for example manysilicate minerals—are chemical substances, but do not have simple formulae reflecting chemically bonding of elements to one another in fixed ratios; even so, thesecrystallinesubstances are often called "non-stoichiometric compounds".It may be argued that they are related to, rather than being chemical compounds, insofar as the variability in their compositions is often due to either the presence of foreign elements trapped within the crystal structure of an otherwise known truechemical compound,or due to perturbations in structure relative to the known compound that arise because of an excess of deficit of the constituent elements at places in its structure; such non-stoichiometric substances form most of thecrustandmantleof the Earth. Other compounds regarded as chemically identical may have varying amounts of heavy or lightisotopesof the constituent elements, which changes the ratio of elements by mass slightly.

Types

Molecules

A molecule is anelectrically neutralgroup of two or more atoms held together by chemical bonds.[16][17][18]A molecule may behomonuclear,that is, it consists of atoms of one chemical element, as with two atoms in theoxygenmolecule (O2); or it may beheteronuclear,a chemical compound composed of more than one element, as withwater(two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom; H2O). A molecule is the smallest unit of a substance that still carries all the physical and chemical properties of that substance.[19]

Ionic compounds

An ionic compound is a chemical compound composed ofionsheld together byelectrostatic forcestermedionic bonding.The compound is neutral overall, but consists of positively charged ions calledcationsand negatively charged ions calledanions.These can besimple ionssuch as thesodium(Na+) andchloride(Cl−) insodium chloride,orpolyatomicspecies such as theammonium(NH+

4) andcarbonate(CO2−

3) ions inammonium carbonate.Individual ions within an ionic compound usually have multiple nearest neighbours, so are not considered to be part of molecules, but instead part of a continuous three-dimensional network, usually in acrystalline structure.

Ionic compounds containing basic ionshydroxide(OH−) oroxide(O2−) are classified as bases. Ionic compounds without these ions are also known assaltsand can be formed byacid–base reactions.Ionic compounds can also be produced from their constituent ions byevaporationof theirsolvent,precipitation,freezing,asolid-state reaction,or theelectron transferreaction ofreactivemetals with reactive non-metals, such ashalogengases.

Ionic compounds typically have highmeltingandboiling points,and arehardandbrittle.As solids they are almost alwayselectrically insulating,but whenmeltedordissolvedthey become highlyconductive,because the ions are mobilized.

Intermetallic compounds

An intermetallic compound is a type ofmetallicalloythat forms an ordered solid-state compound between two or more metallic elements. Intermetallics are generally hard and brittle, with good high-temperature mechanical properties.[20][21][22]They can be classified as stoichiometric or nonstoichiometric intermetallic compounds.[20]

Complexes

A coordination complex consists of a central atom or ion, which is usuallymetallicand is called thecoordination centre,and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions, that are in turn known asligandsor complexing agents.[23][24][25]Many metal-containing compounds, especially those oftransition metals,are coordination complexes.[26]A coordination complex whose centre is a metal atom is called a metal complex of d block element.

Bonding and forces

Compounds are held together through a variety of different types of bonding and forces. The differences in the types of bonds in compounds differ based on the types of elements present in the compound.

London dispersion forcesare the weakest force of allintermolecular forces.They are temporary attractive forces that form when theelectronsin two adjacent atoms are positioned so that they create a temporarydipole.Additionally, London dispersion forces are responsible for condensingnon polarsubstances to liquids, and to further freeze to a solid state dependent on how low the temperature of the environment is.[27]

Acovalent bond,also known as a molecular bond, involves the sharing of electrons between two atoms. Primarily, this type of bond occurs between elements that fall close to each other on theperiodic table of elements,yet it is observed between some metals and nonmetals. This is due to the mechanism of this type of bond. Elements that fall close to each other on the periodic table tend to have similarelectronegativities,which means they have a similar affinity for electrons. Since neither element has a stronger affinity to donate or gain electrons, it causes the elements to share electrons so both elements have a more stableoctet.

Ionic bondingoccurs whenvalence electronsare completely transferred between elements. Opposite to covalent bonding, this chemical bond creates two oppositely charged ions. The metals in ionic bonding usually lose their valence electrons, becoming a positively chargedcation.The nonmetal will gain the electrons from the metal, making the nonmetal a negatively chargedanion.As outlined, ionic bonds occur between an electron donor, usually a metal, and an electron acceptor, which tends to be a nonmetal.[28]

Hydrogen bondingoccurs when ahydrogen atombonded to an electronegative atom forms anelectrostaticconnection with another electronegative atom through interacting dipoles or charges.[29][30][31]

Reactions

A compound can be converted to a different chemical composition by interaction with a second chemical compound via achemical reaction.In this process, bonds between atoms are broken in both of the interacting compounds, and then bonds are reformed so that new associations are made between atoms. Schematically, this reaction could be described asAB + CD → AD + CB,where A, B, C, and D are each unique atoms; and AB, AD, CD, and CB are each unique compounds.

See also

References

- ^Wang, Zhanyun; Walker, Glen W.; Muir, Derek C. G.; Nagatani-Yoshida, Kakuko (2020-01-22)."Toward a Global Understanding of Chemical Pollution: A First Comprehensive Analysis of National and Regional Chemical Inventories".Environmental Science & Technology.54(5): 2575–2584.Bibcode:2020EnST...54.2575W.doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b06379.hdl:20.500.11850/405322.PMID31968937.

- ^abBoyle 1661,p. 41.

- ^Boyle 1661,p. 13.

- ^abcBoyle 1661,p. 29.

- ^abBoyle 1661,p. 42.

- ^Boyle 1661,p. 145.

- ^Boyle 1661,p. 40-41.

- ^Boyle 1661,p. 38.

- ^Watts, Isaac (1726) [1724].Logick: Or, the right use of reason in the enquiry after truth, with a variety of rules to guard against error in the affairs of religion and human life, as well as in the sciences.Printed for John Clark and Richard Hett. pp. 13–15.

- ^Whitten, Kenneth W.; Davis, Raymond E.; Peck, M. Larry (2000),General Chemistry(6th ed.), Fort Worth, TX: Saunders College Publishing/Harcourt College Publishers,ISBN978-0-03-072373-5

- ^Brown, Theodore L.; LeMay, H. Eugene; Bursten, Bruce E.; Murphy, Catherine J.; Woodward, Patrick (2013),Chemistry: The Central Science(3rd ed.), Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson/Prentice Hall, pp. 5–6,ISBN9781442559462,archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-31,retrieved2020-12-08

- ^Hill, John W.; Petrucci, Ralph H.; McCreary, Terry W.; Perry, Scott S. (2005),General Chemistry(4th ed.), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall, p. 6,ISBN978-0-13-140283-6,archivedfrom the original on 2009-03-22

- ^Wilbraham, Antony; Matta, Michael; Staley, Dennis; Waterman, Edward (2002),Chemistry(1st ed.), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall, p.36,ISBN978-0-13-251210-7

- ^Manchester, F. D.; San-Martin, A.; Pitre, J. M. (1994). "The H-Pd (hydrogen-palladium) System".Journal of Phase Equilibria.15:62–83.doi:10.1007/BF02667685.S2CID95343702.Phase diagram for Palladium-Hydrogen System

- ^abAtkins, Peter;Jones, Loretta (2004).Chemical Principles: The Quest for Insight.W.H. Freeman.ISBN978-0-7167-5701-6.

- ^IUPAC,Compendium of Chemical Terminology,2nd ed. (the "Gold Book" ) (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Molecule".doi:10.1351/goldbook.M04002

- ^Ebbin, Darrell D. (1990).General Chemistry(3rd ed.). Boston:Houghton Mifflin Co.ISBN978-0-395-43302-7.

- ^Brown, T.L.; Kenneth C. Kemp; Theodore L. Brown; Harold Eugene LeMay; Bruce Edward Bursten (2003).Chemistry – the Central Science(9th ed.). New Jersey:Prentice Hall.ISBN978-0-13-066997-1.

- ^"Definition of molecule - NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms".NCI.2011-02-02.Retrieved2022-08-26.

- ^abAskeland, Donald R.; Wright, Wendelin J. (January 2015). "11-2 Intermetallic Compounds".The Science and Engineering of Materials(Seventh ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. pp. 387–389.ISBN978-1-305-07676-1.OCLC903959750.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-31.Retrieved2020-11-10.

- ^Panel On Intermetallic Alloy Development, Commission On Engineering And Technical Systems (1997).Intermetallic alloy development: a program evaluation.National Academies Press. p. 10.ISBN0-309-52438-5.OCLC906692179.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-31.Retrieved2020-11-10.

- ^Soboyejo, W. O. (2003). "1.4.3 Intermetallics".Mechanical properties of engineered materials.Marcel Dekker.ISBN0-8247-8900-8.OCLC300921090.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-31.Retrieved2020-11-10.

- ^Lawrance, Geoffrey A. (2010).Introduction to Coordination Chemistry.Wiley.doi:10.1002/9780470687123.ISBN9780470687123.

- ^IUPAC,Compendium of Chemical Terminology,2nd ed. (the "Gold Book" ) (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "complex".doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01203

- ^IUPAC,Compendium of Chemical Terminology,2nd ed. (the "Gold Book" ) (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "coordination entity".doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01330

- ^Greenwood, Norman N.;Earnshaw, Alan (1997).Chemistry of the Elements(2nd ed.).Butterworth-Heinemann.ISBN978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^"London Dispersion Forces".www.chem.purdue.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-01-13.Retrieved2017-09-13.

- ^"Ionic and Covalent Bonds".Chemistry LibreTexts.2013-10-02.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-13.Retrieved2017-09-13.

- ^IUPAC,Compendium of Chemical Terminology,2nd ed. (the "Gold Book" ) (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "hydrogen bond".doi:10.1351/goldbook.H02899

- ^"Hydrogen Bonding".www.chem.purdue.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-08-08.Retrieved2017-10-28.

- ^"intermolecular bonding – hydrogen bonds".www.chemguide.co.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-12-19.Retrieved2017-10-28.

Sources

- Boyle, R. (1661).The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes, Touching the Spagyrist's Principles Commonly call'd Hypostatical; As they are wont to be Propos'd and Defended by the Generality of Alchymists. Whereunto is præmis'd Part of another Discourse relating to the same Subject.Printed by J. Cadwell for J. Crooke.

Further reading

- Robert Siegfried (1 October 2002),From elements to atoms: a history of chemical composition,American Philosophical Society,ISBN978-0-87169-924-4