Chlorella

| Chlorella | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chlorella vulgaris | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | Viridiplantae |

| Division: | Chlorophyta |

| Class: | Trebouxiophyceae |

| Order: | Chlorellales |

| Family: | Chlorellaceae |

| Genus: | Chlorella M.Beijerinck, 1890 |

| Species | |

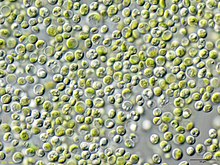

Chlorellais agenusof about thirteen species of single-celledgreen algaeof the divisionChlorophyta.The cells are spherical in shape, about 2 to 10μmin diameter, and are withoutflagella.Theirchloroplastscontain the green photosynthetic pigmentschlorophyll-aand-b.In ideal conditions cells ofChlorellamultiply rapidly, requiring onlycarbon dioxide,water,sunlight,and a small amount ofmineralsto reproduce.[1]

The nameChlorellais taken from theGreekχλώρος,chlōros/ khlōros,meaning green, and theLatindiminutive suffixella,meaning small. Germanbiochemistand cell physiologistOtto Heinrich Warburg,awarded with theNobel Prize in Physiology or Medicinein 1931 for his research oncell respiration,also studied photosynthesis inChlorella.In 1961,Melvin Calvinof theUniversity of Californiareceived theNobel Prize in Chemistryfor his research on the pathways ofcarbon dioxide assimilation in plantsusingChlorella.

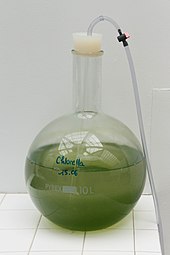

Chlorellahas been considered as a source of food and energy because itsphotosynthetic efficiencycan reach 8%,[2]which exceeds that of other highly efficient crops such assugar cane.

Taxonomy

[edit]Chlorellawas first described byMartinus Beijerinckin 1890. Since then, over a hundred taxa have been described within the genus. However, biochemical and genomic data has revealed that many of these species were not closely related to each other, even being placed in a separate classChlorophyceae.In other words, the "green ball" form ofChlorellaappears to be a product ofconvergent evolutionand not a natural taxon.[3]IdentifyingChlorella-like algae based on morphological features alone is generally not possible.[4]

Some strains of "Chlorella" used for food are incorrectly identified, or correspond to genera that were classified out of trueChlorella.For example,Heterochlorella luteoviridisis typically known asChlorella luteoviridiswhich is no longer considered a valid name.[5]

As a food source

[edit]When first harvested,Chlorellawas suggested as an inexpensive protein supplement to the human diet. According to theAmerican Cancer Society,"available scientific studies do not support its effectiveness for preventing or treating cancer or any other disease in humans".[6]

Under certain growing conditions,Chlorellayields oils that are high inpolyunsaturated fats—Chlorella minutissimahas yieldedeicosapentaenoic acidat 39.9% of total lipids.[7]

History

[edit]Following global fears of an uncontrollable human population boom during the late 1940s and the early 1950s,Chlorellawas seen as a new and promising primary food source and as a possible solution to the then-current world hunger crisis. Many people during this time thought hunger would be an overwhelming problem and sawChlorellaas a way to end this crisis by providing large amounts of high-quality food for a relatively low cost.[8]

Many institutions began to research the algae, including theCarnegie Institution,theRockefeller Foundation,theNIH,UC Berkeley,theAtomic Energy Commission,andStanford University.FollowingWorld War II,many Europeans were starving, and manyMalthusiansattributed this not only to the war, but also to the inability of the world to produce enough food to support the increasing population. According to a 1946FAOreport, the world would need to produce 25 to 35% more food in 1960 than in 1939 to keep up with the increasing population, while health improvements would require a 90 to 100% increase.[8]Because meat was costly and energy-intensive to produce, protein shortages were also an issue. Increasing cultivated area alone would go only so far in providing adequate nutrition to the population. TheUSDAcalculated that, to feed the U.S. population by 1975, it would have to add 200 million acres (800,000 km2) of land, but only 45 million were available. One way to combat national food shortages was to increase the land available for farmers, yet the American frontier and farm land had long since been extinguished in trade for expansion and urban life. Hopes rested solely on new agricultural techniques and technologies. Because of these circumstances, an alternative solution was needed.

To cope with the upcoming postwar population boom in the United States and elsewhere, researchers decided to tap into the unexploited sea resources. Initial testing by theStanford Research InstituteshowedChlorella(when growing in warm, sunny, shallow conditions) could convert 20% of solar energy into a plant that, when dried, contains 50% protein.[8]In addition,Chlorellacontains fat and vitamins. The plant's photosynthetic efficiency allows it to yield more protein per unit area than any plant—one scientist predicted 10,000 tons of protein a year could be produced with just 20 workers staffing a 1000-acre (4-km2)Chlorellafarm.[8]The pilot research performed at Stanford and elsewhere led to immense press from journalists and newspapers, yet did not lead to large-scale algae production.Chlorellaseemed like a viable option because of the technological advances in agriculture at the time and the widespread acclaim it got from experts and scientists who studied it. Algae researchers had even hoped to add a neutralizedChlorellapowder to conventional food products, as a way to fortify them with vitamins and minerals.[8]

When the preliminary laboratory results were published, the scientific community at first backed the possibilities ofChlorella.Science News Letterpraised the optimistic results in an article entitled "Algae to Feed the Starving". John Burlew, the editor of theCarnegie Institution of WashingtonbookAlgal Culture-from Laboratory to Pilot Plant,stated, "the algae culture may fill a very real need",[9]whichScience News Letterturned into "future populations of the world will be kept from starving by the production of improved or educated algae related to the green scum on ponds". The cover of the magazine also featuredArthur D. Little's Cambridge laboratory, which was a supposed future food factory. A few years later, the magazine published an article entitled "Tomorrow's Dinner", which stated, "There is no doubt in the mind of scientists that the farms of the future will actually be factories."Science Digestalso reported, "common pond scum would soon become the world's most important agricultural crop." However, in the decades since those claims were made, algae have not been cultivated on that large of a scale.

Current status

[edit]Since the growing world food problem of the 1940s was solved by better crop efficiency and other advances in traditional agriculture,Chlorellahas not seen the kind of public and scientific interest that it had in the 1940s.Chlorellahas only a niche market for companies promoting it as a dietary supplement.[8]

Production difficulties

[edit]

The experimental research was carried out in laboratories, rather than in the field, and scientists discovered thatChlorellawould be much more difficult to produce than previously thought. To be practical, the algae grown would have to be placed either inartificial lightor in shade to produce at its maximum photosynthetic efficiency. In addition, for theChlorellato be as productive as the world would require, it would have to be grown incarbonated water,which would have added millions to the production cost. A sophisticated process, and additional cost, was required to harvest the crop and forChlorellato be a viable food source, its cell walls would have to be pulverized. The plant could reach its nutritional potential only in highly modified artificial situations. Another problem was developing sufficiently palatable food products fromChlorella.[10]

Although the production ofChlorellalooked promising and involved creative technology, it has not to date been cultivated on the scale some had predicted. It has not been sold on the scale ofSpirulina,soybeanproducts, or whole grains. Costs have remained high, andChlorellahas for the most part been sold as a health food, for cosmetics, or asanimal feed.[10]After a decade of experimentation, studies showed that following exposure to sunlight,Chlorellacaptured just 2.5% of the solar energy, not much better than conventional crops.[8]Chlorella,too, was found by scientists in the 1960s to be impossible for humans and other animals to digest in its natural state due to the tough cell walls encapsulating the nutrients, which presented further problems for its use in American food production.[8]

Use in carbon dioxide reduction and oxygen production

[edit]In 1965, the RussianCELSSexperimentBIOS-3determined that 8 m2of exposedChlorellacould remove carbon dioxide and replace oxygen within the sealed environment for a single human. The algae were grown in vats underneath artificial light.[11]

Dietary supplement

[edit]

Chlorellais consumed as adietary supplement.Some manufacturers ofChlorellaproducts have falsely asserted that it has health benefits,[12]including an ability to treat cancer,[13]for which theAmerican Cancer Societystated "available scientific studies do not support its effectiveness for preventing or treating cancer or any other disease in humans".[13]The United StatesFood and Drug Administrationhas issuedwarning lettersto supplement companies for falsely advertising health benefits of consuming chlorella products, such as one company in October 2020.[14]

There is some support from animal studies of chlorella's ability to detoxifyinsecticides.Chlorella protothecoidesaccelerated the detoxification of rats poisoned withchlordecone,a persistent insecticide, decreasing the half-life of the toxin from 40 to 19 days.[15]The ingested algae passed through the gastrointestinal tract unharmed, interrupted the enteric recirculation of the persistent insecticide, and subsequently eliminated the bound chlordecone with the feces.

Vitamin B12

[edit]Chlorella is being investigated as a possible plant-based source of biologically active Vitamin B12 (notB12 analogues). Although current studies show it to have a high B12 content and low levels of analogues,[16][17]it can vary widely among different commercial products, from <0.1 to 400 μg per 100 g of dry weight. AmongChlorellaspecies, the B12content is much higher inC. pyrenoidosathan inC. vulgariswhen grown under open culture conditions.[16][18]Reasons for the wide variations is still unknown. Thus,vegetariansandveganswho consumeChlorellaas a plant based source of Vitamin B12should check the nutrition labeling ofChlorellaproducts to confirm their actual Vitamin B12contents.[19].ThereforeChlorellaproducts with high B12and without inactive corrinoid compounds are suitable for use as B12sources in humans, particularly vegans.[20][21]

Health concerns

[edit]A 2002 study showed thatChlorellacell walls containlipopolysaccharides,endotoxinsfound inGram-negative bacteriathat affect theimmune systemand may causeinflammation.[22][23][24]However, more recent studies have found that the lipopolysaccharides in organisms other than Gram-negative bacteria, for example in cyanobacteria, are considerably different from the lipopolysaccharides in Gram-negative bacteria.[25]

See also

[edit]- Calvin cycle

- List of ineffective cancer treatments

- Quorn (food product):made from mycoprotein

- Soyuz 28,a 1978 space mission which included experiments onChlorella

- Spirulina (dietary supplement)

- Chlorellosis,a disease caused by the infection ofChlorella.

References

[edit]- ^Scheffler, John (3 September 2007)."Underwater Habitats".Illumin.9(4).

- ^Zelitch, I. (1971).Photosynthesis, Photorespiration and Plant Productivity.Academic Press.p. 275.

- ^Krienitz, Lothar; Huss, Volker A.R.; Bock, Christina (2015). "Chlorella:125 years of the green survivalist ".Trends in Plant Science.20(2): 67–69.Bibcode:2015TPS....20...67K.doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2014.11.005.PMID25500553.

- ^Matthews, Robin (2016). "Freshwater Algae in Northwest Washington, Volume II, Chlorophyta and Rhodophyta".A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs.Western Washington University.doi:10.25710/fctx-n773.

- ^Champenois, Jennifer; Marfaing, Hélène; Pierre, Ronan (2015). "Review of the taxonomic revision ofChlorellaand consequences for its food uses in Europe ".Journal of Applied Phycology.27(5): 1845–1851.Bibcode:2015JAPco..27.1845C.doi:10.1007/s10811-014-0431-2.S2CID254605212.

- ^"Chlorella".American Cancer Society.29 April 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 5 September 2013.Retrieved23 August2013.

- ^Yongmanitchai, W; Ward, OP (1991)."Growth of and omega-3 fatty acid production by Phaeodactylum tricornutum under different culture conditions".Applied and Environmental Microbiology.57(2): 419–25.Bibcode:1991ApEnM..57..419Y.doi:10.1128/AEM.57.2.419-425.1991.PMC182726.PMID2014989.

- ^abcdefghBelasco, Warren (July 1997). "Algae Burgers for a Hungry World? The Rise and Fall of Chlorella Cuisine".Technology and Culture.38(3): 608–34.doi:10.2307/3106856.JSTOR3106856.S2CID109494408.

- ^Burlew, John, ed. (1953).Algal Culture-from Laboratory to Pilot Plant.Carnegie Institution of Washington. p. 6.ISBN978-0-87279-611-9.

- ^abBecker, E.W. (2007). "Micro-algae as a source of protein".Biotechnology Advances.25(2): 207–10.doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2006.11.002.PMID17196357.

- ^"Russian CELSS Studies".Space Colonies.PERMANENT.Retrieved24 June2024.

- ^Sun Chlorella, Going Green from the Inside Out – LA Sentinel

- ^ab"Chlorella".American Cancer Society.29 April 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 5 September 2013.Retrieved13 September2013.

- ^William A. Correll (20 October 2020)."FDA Warning Letter to ForYou Inc".Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations, US Food and Drug Administration.Retrieved9 March2021.

- ^Pore, R. Scott (1984)."Detoxification of Chlordecone Poisoned Rats with Chlorella and Chlorella Derived Sporopollenin".Drug and Chemical Toxicology.7(1): 57–71.doi:10.3109/01480548409014173.ISSN0148-0545.PMID6202479.

- ^abKittaka-Katsura, Hiromi; Fujita, Tomoyuki; Watanabe, Fumio; Nakano, Yoshihisa (14 August 2002)."Purification and characterization of a corrinoid compound from Chlorella tablets as an algal health food".Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.50(17): 4994–4997.doi:10.1021/jf020345w.ISSN0021-8561.PMID12166996.

- ^Chen, Jing-Huan; Jiang, Shiuh-Jen (27 February 2008)."Determination of cobalamin in nutritive supplements and chlorella foods by capillary electrophoresis-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry".Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.56(4): 1210–1215.doi:10.1021/jf073213h.ISSN0021-8561.PMID18247530.

- ^Watanabe, Fumio; Abe, Katsuo; Takenaka, Shigeo; Tamura, Yoshiyuki; Maruyama, Isao; Nakano, Yoshihisa (January 1997)."Occurrence of Cobalamin Coenzymes in the Photosynthetic Green Alga, Chlorella vulgaris".Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry.61(5): 896–897.doi:10.1271/bbb.61.896.ISSN1347-6947.PMID28862557.

- ^Watanabe, Fumio; Yabuta, Yukinori; Bito, Tomohiro; Teng, Fei (5 May 2014)."Vitamin B12-Containing Plant Food Sources for Vegetarians".Nutrients.6(5): 1861–1873.doi:10.3390/nu6051861.ISSN2072-6643.PMC4042564.PMID24803097.

- ^Bito, Tomohiro; Okumura, Eri; Fujishima, Masaki; Watanabe, Fumio (20 August 2020)."Potential of Chlorella as a Dietary Supplement to Promote Human Health".Nutrients.12(9): 2524.doi:10.3390/nu12092524.ISSN2072-6643.PMC7551956.PMID32825362.

- ^Merchant, Randall Edward; Phillips, Todd W.; Udani, Jay (December 2015)."Nutritional Supplementation with Chlorella pyrenoidosa Lowers Serum Methylmalonic Acid in Vegans and Vegetarians with a Suspected Vitamin B12Deficiency ".Journal of Medicinal Food.18(12): 1357–1362.doi:10.1089/jmf.2015.0056.ISSN1557-7600.PMID26485478.

- ^Sasik, Roman (19 January 2012)."Trojan horses ofChlorella'superfood'".Robb Wolf.

- ^Armstrong, PB; Armstrong, MT; Pardy, RL; Child, A; Wainwright, N (2002). "Immunohistochemical demonstration of a lipopolysaccharide in the cell wall of a eukaryote, the green alga, Chlorella".The Biological Bulletin.203(2): 203–4.doi:10.2307/1543397.JSTOR1543397.PMID12414578.

- ^Qin, Liya; Wu, Xuefei; Block, Michelle L.; Liu, Yuxin; Breese, George R.; Hong, Jau-Shyong; Knapp, Darin J.; Crews, Fulton T. (2007)."Systemic LPS causes chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration".Glia.55(5): 453–62.doi:10.1002/glia.20467.PMC2871685.PMID17203472.

- ^Stewart, Ian; Schluter, Philip J; Shaw, Glen R (2006)."Cyanobacterial lipopolysaccharides and human health – a review".Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source.5(1): 7.Bibcode:2006EnvHe...5....7S.doi:10.1186/1476-069X-5-7.PMC1489932.PMID16563160.