Cymbospondylus

| Cymbospondylus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Partial holotype skeleton ofC. buchseri(PIMUZ T 4351), on display at the Paleontological Museum of theUniversity of Zurich,Switzerland. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Ichthyosauria |

| Family: | †Cymbospondylidae |

| Genus: | †Cymbospondylus Leidy,1868 |

| Type species | |

| †Cymbospondylus piscosus nomen dubium Leidy, 1868

| |

| Otherspecies | |

| Synonyms | |

Cymbospondylus(meaning "cupped vertebrae" ) is anextinctgenusof largeichthyosaurs,of which it is among the oldest representatives, that lived from theLowertoMiddle Triassicin what are nowNorth AmericaandEurope.The first knownfossilsof thistaxonare a set of more or less completevertebraewhich were discovered in the 19th century in theFossil Hill memberoutcropping in variousmountain rangesofNevada,in theUnited States,before being named and described byJoseph Leidyin 1868. It is in the beginning of the 20th century that more complete fossils were discovered through several expeditions launched by theUniversity of California,and described in more detail byJohn Campbell Merriamin 1908, thus visualizing the overall anatomy of the animal. While manyspecieshave been assigned to the genus, only five are recognized asvalid,the others being consideredsynonymous,doubtfulor belonging to other genera.Cymbospondyluswas formerly classified as a representative of theShastasauridae,but more recent studies consider it to be morebasal,view as thetype genusof theCymbospondylidae.

As an ichthyosaur,Cymbospondylushadflippersfor limbs and afin on the tail.Like other non-parvipelvianichthyosaurs,Cymbospondylushas a very slender profile, unlike later ichthyosaurs which have a morphology similar to those ofdolphins.The different species ofCymbospondylusvary greatly in size, with the smallest reaching around 4 to 5 metres (13 to 16 ft) in length. The largest known species,C. youngorum,is estimated over 17 metres (56 ft) long, makingCymbospondylusone of the largest ichthyosaurs identified to date, but also one of the largestanimalsknown of its time. The animal has askullwith a long, thinsnout,proportionally smalleye sockets,an elongatedtrunk,and a less pronouncedtailthan in later ichthyosaurs. Theteethare conical and pointed, having longitudinal ridges, indicating a diet offishesandcephalopods,and possibly othermarine reptilesfor larger species.

Unlikecetaceans,Triassicichthyosaurs likeCymbospondylusshow that they reached large sizes very quickly after their appearance, probably because of theadaptive radiationof their prey,conodontsandammonites,after thePermian–Triassic extinction.The size of ichthyosaurs began to decrease later, notably due to the increase in the size of theireyes,which were very useful for spotting prey. All established species ofCymbospondylusare known from the fossil records of Nevada andSwitzerland,with referred specimenswithout specific affiliationshaving nevertheless been discovered inIdaho,the rest of theAlpsandSpitsbergen,an island inNorway.Theformationswhere the recognized species were discovered show thatCymbospondyluslived in marine ecosystems alongsidemolluscslikebivalvesand ammonites,bony fisheslikeSaurichthysandcoelacanths,cartilaginous fisheslikehybodonts,and marine reptiles likesauropterygiansand other ichthyosaurs. The different ichthyosaurs from these localities would have used different feeding strategies toavoid competition.

Research history[edit]

Discovery and identification[edit]

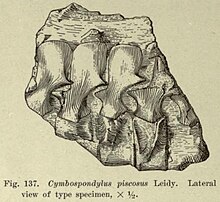

In 1868,AmericanpaleontologistJoseph Leidydescribed two newgeneraofichthyosaursdating from theMiddle Triassicon the basis offossilvertebraediscovered in several localities inNevada,United States,all of which were transmitted through the geologistJosiah Dwight Whitney.One of the two genera he names isCymbospondylus,to which he assigns two species. The first one isC. piscosus,which Leidy named on the basis of several more or less complete vertebrae having been discovered in differentmountain rangesof thestate.[1]TheholotypeofC. piscosusis a block containing five incompletedorsal vertebraethat was discovered in theNew Pass Range,northwest of the city ofAustin.[2][3][4][5][a]Leidy attributes two other specimens to the species, one being a series of eight caudal vertebrae discovered at Star Canyon in theHumboldt Range,and the other being a single vertebrae, probably also caudal, discovered in theToiyabe Range,in theReese River,northeast of Austin. The second species isC. petrinus,named from five large dorsal vertebrae discovered in the Humboldt Range.[1]Thegenus nameCymbospondylusderives from theAncient Greekwords κύμβη (kymbē,"cup" ) and σπόνδυλος (spondylos,"vertebra" ), all taken together literally meaningcupped vertebrae,in reference to the rather obvious shape of this part of theskeleton.[6]As notype specieswas designated in the 1868 article, it was not until 1902 thatJohn Campbell MerriamassignedC. piscosusto this title,[2]the latter being the first named in Leidy's official description of the genus.[1]

Between 1901 and 1907, theUniversity of Californiasent ten expeditions across different corners of the United States to recover as many ichthyosaur fossils as possible dating from the Triassic, in order to be analyzed in more detail. These same expeditions were led by Merriam and were almost all financed byAnnie Montague Alexander.The research finally collected more than fifty specimens, each preserving a significant portion of their skeletons.[7]Among these fossils are several specimens of excellent quality fromC. petrinus,including an almost complete skeleton, cataloged as UCMP 9950, all discovered in the origin locality mentioned by Leidy atFossil Hill.Like the other ichthyosaurs mentioned in the work, Merriam describes the taxon in more depth based on new known fossil material.[8]Merriam's anatomical descriptions ofC. petrinusare still recognized as viable, and are even used incomparative anatomyin later studies of the genusCymbospondylus,thus lendingvalidityto the species.[4][9][5][10][11]

UnlikeC. petrinus,no additional fossils of the type speciesC. piscosushave been discovered. In Merriam's works, the latter recognizedC. piscosusas distinct on the basis of its smaller size and by the regularly concave faces of the vertebrae of the holotype specimen.[2][12]Only later did the validity ofC. piscosusbegin to be questioned, with authors mentioning the questionable nature of the fossils.[4]In their work published in 2003, Christopher McGowan and Ryosuke Motani assert that the fossil vertebrae attributed toC. piscosusdo not present distinctive characteristics to prove its validity. This would therefore pose a taxonomic problem, because if the type species turns out to be anomen dubium,the genus to which it is classified will also be. To try to resolve this problem, the two authors suggest that the most complete known skeleton ofC. petrinus(UCMP 9950) could be designated as aneotypeofC. piscosus.[13]However, as no formalICZNappeal has been established to date, the nameC. petrinusfor the proposed neotype should be retained until further notice.[5]In 2017, Andrzej Stefan Wolniewicz referred all additional fossil material described by Merriam toC. piscosusand synonymizedC. petrinusto the latter.[14]However, As the proposal remains restricted to aPhDthesis,it is defined as an unpublished work per Article 8 of the ICZN and therefore is not formally valid.[15][16]Therefore,C. piscosusis not included in most descriptions of the genus, although it is still recognized as the type species.[10][11]

Recognized species[edit]

In 1927, a partial skeleton of a large ichthyosaur was discovered in theGrenzbitumenzoneMember at theMonte San Giorgiofossil site inSwitzerlandand was mentioned byBernhard Peyerin 1944.[17]Twenty years later, in 1964,Emil Kuhn-Schnyderpublished a photo of this same specimen and suggested that it shared affinities withCymbospondylus,then only known fromNorth Americaat that time.[18]The specimen in question, cataloged as PIMUZ T 4351, was formally described for the first time in 1989 under the nameC. buchseribyPaul Martin Sander,thus confirming the presence of the genus inEurope.Thespecific epithetbuchseriis named in honor of Fritz Buchser, a member of the Museum of Paleontology at theUniversity of Zurich,the latter having prepared the holotype skeleton in 1931 as his first major professional achievement.[4]

WhileC. petrinuswas for a time seen as the only valid species of the genus known from Nevada, it was not until the early 21th century that later discoveries contradicted this assertion. In 2006, Nadia Fröbisch and colleagues described the speciesC. nichollsibased on an incomplete skeleton, cataloged as FMNH PR 2251, which was discovered in theAugusta Mountains.The fossil was originally exhumed in the hope of finding a new specimen ofC. petrinus,but the number of significant anatomical differences led researchers to establish a separate species. The species in question is named in honor toElizabeth Nicholls,an American-Canadianpaleontologist specializing in Triassicmarine reptiles,who made a major contribution to the ichthyosaurs that lived during this period.[5][6]In their description, Fröbisch and his colleagues consider that an almost complete skull attributed toC. petrinus,cataloged as UCMP 9913,[b]could in fact belong toC. nichollsi,because it presents similar characteristics. However, as the specimen has been relatively little described in thescientific literature,the authors do not know whether it would showintraspecific variationswithinC. petrinus,judging therefore that a more in-depth description is necessary.[5]Subsequent studies carried out on the genusCymbospondylusnevertheless always refer specimen UCMP 9913 toC. petrinus,[20]but still mentioning some notable differences.[10]In his thesis published in 2017, Wolniewicz redescribedC. nichollsianatomically and considered it a "subjective junior synonym ofC. piscosus",[21]but its observation is not shared and the species is maintained valid in subsequent publications.[10][11][20]

In 2011, a notable newCymbospondylusfossil was also discovered in the Augusta Mountains, then exhumed three years later in 2014. This discovery was a partial skeleton that was briefly mentioned in a 2013 in a secondary article describing the large contemporary ichthyosaurThalattoarchon,[22]as well as in a 2018histologicalstudy, where it is among the specimens analyzed.[23]However, it was only later that the specimen, cataloged asLACMDI 158109, was formally designated a holotype for the speciesC. duelferiby Nicole Klein and colleagues in 2020. The species nameduelferiwas chosen in honor of Olaf Dülfer, fossil preparer who made many practical contributions to research onMesozoicmarine reptiles.[10][6]

In 1998, still in the Augusta Mountains, Sander discovered another notable specimen ofCymbospondylus,and exhumed it with his colleagues between 2014 and 2015.[20]After preparation of the fossils, the specimen, cataloged as LACM DI 157871, consists of a large complete skull, somecervical vertebrae,the righthumerusas well as fragments of theshoulder girdle.It was in 2021, one year after the identification ofC. duelferi,that a new species of the genus was named from this specimen inScienceby Sander and his colleagues.[11][20]This species,C. youngorum,is named in honor of Tom and Bonda Young,[11]these latter having financially supported the fossil exhumation project.[24]

Specimens that may belong to the genus[edit]

Many other more partial specimens ofCymbospodylushave been discovered in various geological formations in Europe, but their specific attribution cannot be determined, the latter are then referred to under the nameCymbospondylussp.in thescientific literature.Three of these specimens, including one fromIdaho,and two from theNorwegianarchipelagoofSvalbard,are dated to theOlenekianstageof theLower Triassic,making them the oldest known representatives of the genus.[25][26][27]Below, the list of specimens that could potentially belong toCymbospondylus:

- In 1980, Kuhn-Schnyder described an anterior partial skeleton of an ichthyosaur discovered inMonte Seceda,Italy. The described specimen was first referred by the author toShastasaurussp.,[28]before being referred toCymbospondylusin the official description ofC. buchseriby Sander in 1989,[4]an attribution which seems to still be recognized today.[29]

- In 1992, Sander described two specimens attributed toCymbospondylushaving been discovered in different localities ofSpitsbergen,located in theNorwegianarchipelagoofSvalbard.The first and the better preserved of the two specimens described in the article, consists of a series of 17 vertebrae associated with ribs which was discovered in 1961 in theBotneheiamountain, being cataloged as PIMUZ A/III 496. The second consists of two isolated vertebrae, cataloged as PIMUZ A/III 554 and 555, which were both discovered in thebayofWichebukta.[30]

- In 1994,Judy A. Massareand Jack M. Callaway referred to a number ofCymbospondylusfossils discovered in 1985 by H. Gregory McDonald in the Platy Siltstone Member of theThaynes Formation,in Idaho, United States.[25]

- In 2001, Olivier Rieppel and Fabio Marco Dalla Vecchia listed a set of fossils of marine reptiles from the Triassic and having been discovered in thecomuneofForni di Sotto,in Italy, including two that they attributed with doubt toCymbospondylus.The first of these collections consists of a single vertebra, a neural spine and three rib fragments, while the second consists of two isolated vertebrae.[31]

- In 2012, Balini and Renesto described four more or less partial vertebrae attributed toCymbospondyluswhich were discovered in thecomuneofPiazza Brembana,in Italy, being cataloged MCSNB 11689 A, B, C, and D.[29]

- In 2013 and 2018, numerous genus-assigned vertebrae were identified in the Vendomdalen Member of theVikinghøgda Formation,Svalbard.[32][26][27]

Formerly assigned species[edit]

Although many valid anddistinctspecies have been assigned toCymbospondylusthroughout itstaxonomichistory, some of these have been reassigned to different genera or are consideredsynonymousor evendoubtful.[5]In his 1868 paper describingCymbospondylus,Leidy also named another ichthyosaur asChonespondylus grandis,based on a fragment of a caudal vertebra found at Star Canyon in the Humboldt Range.[1]The genus nameChonespondylusderives from the Ancient Greek words χοάνη (khoánē,"funnel" ) and σπόνδυλος (spondylos,"vertebra" ) named in the same way as forCymbospondylus.The specific epithet comes from theLatingrandis,meaning "large, wide".[6]In 1902, Merriam listed Leidy's discoveries, but having found no features distinguishingChonespondylusfromCymbospondylus,he decided to synonymize the first name with the second, under the nameC. (?) grandis.[33]In 1908, after the discovery of new very complete fossils fromC. petrinus,Merriam decided to definitively synonymizeC. (?) grandiswith the latter.[34][5]

In 1873,John Whitaker Hulkedescribed a species ofIchthyosaurus,I. polaris,named after two sets of vertebrae associated with rib fragments that were discovered onIsfjorden,Spitsbergen,an island inNorway.[35]In 1902, theRussianpaleontologist Nikolai Nikolajewitch Yakowlew moved the species within the genusShastasaurus,referring an isolated vertebra to this taxon.[36]In 1908, Merriam in turn moved this species into the genusCymbospondylus,under the nameC. (?) polaris.Merriam still expresses some hesitation about this attribution, asserting that the true generic identity cannot be determined for this species due to the few known fossils.[37]In 1910, the species was moved to the newly erected genusPessosaurusbyCarl Wiman,asP. polaris,[38]to which it has always been referred by this name ever since. Although this taxon is declared as anomen dubiumaccording to studies published at the end of the 20th century, it is seen as aspecies inquirendaaccording to McGowan and Motani in 2003, i.e. a taxon under investigation, as numerous fossils that have since been referred toP. polariscould make it once again as valid.[39]

Still in his 1908 work, Merriam erects two new species of the genus, coming from the same locality from whichC. petrinusis known. The first isC. nevadanus,named from fossils constituting a hind limb. Merriam distinguishes this species fromC. petrinuson the basis of its larger size and the different proportions of somebones.[40]However, theC. nevadanusmaterial is not sufficiently diagnostic to support the validity of this species, and is considered aspecies inquiredaaccording to McGowan and Motani in 2003.[41][5]The second species erected by Merriam isC. natans,which he names from an isolated humerus, to which he attributes aradius,anulna,carpalsand a series of caudal vertebrae. In his article, he notes the similarity of these bones with those ofMixosaurus,[42]leading the author to rename the species toM (?) natansin 1911.[43]For much of the 20th century,M (?) natanswas recognized as a valid species ofMixosaurusuntil 1999, when it was synonymized withM. nordenskioeldii.[44]AlthoughM. nordenskioeldiiitself has been considered anomen dubiumsince 2005,[45]the fossil material concerned remains attributed to thefamilyMixosauridaeand is no longer attributable toCymbospondylus.[5]

In a review of German ichthyosaurs published in 1916,Friedrich von Huenedescribed two other species ofCymbospondyluswhose fossils were discovered in theMuschelkalkof the town ofLaufenburgin thestateofBaden-Württemberg.The first isC. germanicus,which Huene names from a single vertebra associated with other vertebrae as well as abasioccipital.[46]Immediately afterwards, the validity ofC. germanicuswas questioned the same year byFerdinand Broili,the latter citing that the fossils concerned did not present notable features to be recognized as distinct.[47][5]Additionally, the fossils appear to be very poorly preserved to be distinguished as a valid species,[4]and is therefore anomen dubium.[48][49]

In 2002, paleontologists Chun Li and Hai-Lu You named a new species asC. asiaticusbased on a complete skull discovered in theXiaowa Formation,located inGuizhou Province,China,and it was considered as the most recent known representative of the genus.[50]In the official description ofC. nichollsipublished in 2006, the authors are doubtful regarding the attribution of this species toCymbospondylus.They mention that the latter does not share any notable commonalities with the three then recognized species of the genus at the time, namelyC. petrinus,C. buchseriandC. nichollsi,and suggest that it would in fact be a junior synonym ofGuizhouichthyosaurus tangae.[5]The synonymy proposed by Fröbisch and colleagues was accepted in 2009 by Qing-Hua Shang and Li after the discovery of an almost complete skeleton ofGuizhouichthyosaurusfrom the same formation. However, considering thatGuizhouichthyosaurusis similar toShastasaurus,they moved the species asS. tangae.[51]This synonymy was contested the following year, in 2010, in which Michael W. Maisch provisionally reclassifiedGuizhouichthyosaurusas a distinct genus.[52]In 2011, Sander and his colleagues considered thatGuizhouichthyosauruswas distinct,[53]while a 2013 study by Shang and Li still synonymizes it withShastasaurus.[54]However, numerousphylogeneticand morphological analyzes subsequently published considerGuizhouichthyosaurusto be distinct genus fromShastasaurus.[55][56][57][58]

Description[edit]

Cymbospondylus,like other ichthyosaurs, had a long, thinsnout,largeeye sockets,and atail flukethat was supported by vertebrae in the lower half. Ichthyosaurs were superficially similar todolphinsand hadflippersrather than legs, but the oldest representatives (with the exception of theparvipelvians,moreadvanced) do not havedorsal fins,or would have one but relatively poorly developed.[59]Like most Triassic ichthyosaurs,Cymbospondylushas a more slender anatomy, possessing an elongatedtrunkand a long, poorly pronounced tail.[60][61][29][62]Although the colour ofTemnodontosaurusis unknown, at least some ichthyosaurs may have been uniformly dark-coloured in life, which is evidenced by the discovery of high concentrations ofeumelaninpigments in the preserved skin of an early ichthyosaur fossil.[63]

Size[edit]

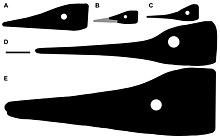

The size and weight ofCymbospondylusvaries greatly between recognized species.[5][10][27]Estimates of the size ofC. petrinushave changed relatively little since 1908, mainly due to the almost complete skeleton of specimen UCMP 9950, considered the best known specimen ofCymbospondylus.[64]Merriam suggests thatC. petrinuswould reach a size exceeding 9.1 m (360 in) in length based on specimens UCMP 9947 and 9950.[65][4][5]In 2020, Klein and colleagues increased the size estimate ofC. petrinusa little further, seeing them as reaching 9.3 m (31 ft) for a 1.16 m (3 ft 10 in) skull.[10]In 2021, Sander and is colleagues in 2021 estimatesC. petrinusto 12.56 m (41 ft 2 in) long for about 5.7 metric tons (6.3 short tons), while keeping the same cranial measurements.[20]The explanation for the origin of this size is described in a paper published in 2024. The study explains that Sander made a further revision regarding the size ofC. petrinusbased on specimens UCMP 9947 and 9950, and suggested that the combination of the two gives a total of approximately 10 m (33 ft). Specimen UCMP 9947 is missing several posterior caudal vertebrae, so the increase in size to over 11 to 12 m (36 to 39 ft) long is not seen as unreasonable.[27]The holotype specimen ofC. youngorumhaving a skull measuring almost 2 m (6.6 ft) long and its humerus being the second largest bone of this type recorded in an ichthyosaur, the maximum size of the animal is therefore estimated at 17.65 m (57.9 ft) for a weight of 44.7 metric tons (49.3 short tons).[c]This estimate not only makesC. youngourumone of the largest ichthyosaurians identified to date behindIchthyotitan,but also makes it one of the largest animals known of its time.[11][27][66]The antiquity as well as such an imposing size for an animal dating from the beginning of the Middle Triassic makesC. youngorumqualify as "the first aquatic giant" according to Lene Liebe Delsett andNicholas David Pyenson.[24]

Estimating the size ofC. nichollsiis more complex, because although the holotype specimen is known from a significant portion of the skeleton, the latter preserves only half of the skull. However, based on the comparison withC. buchseriandC. petrinus,the total length of the skull is estimated at 97 cm (3 ft 2 in) for an animal measuring 7.6 m (25 ft) long,[5][10][27]all for a body mass of 3 metric tons (3.3 short tons).[20]The estimated size of theC. buchseriholotype is slightly shorter, reaching a length of 5 to 5.5 m (16 to 18 ft) with a skull 68 cm (2 ft 3 in) long, although no estimate of its weight has yet been published.[4][58][27]Possessing a skull which would measure a total of 65–70 cm (2 ft 2 in – 2 ft 4 in),C. duelferiis the smallest known species of the genus, having a size estimated at 4.3 m (14 ft) long in the study officially describing it.[10]The measurements of the species are estimated again at around 5 m (16 ft) for abody massof 520 kg (1,150 lb) by Sander and colleagues in 2021.[20][27]

Individuals with undetermined specific attributions have also been given estimates regarding their size, although known from thinner fossil remains. Using the same measurement technique as those done forC. youngorum,a specimen cataloged as IGPB R660, known from the Vikinghøgda Formation, has an estimated size between 7.5 to 9.5 m (25 to 31 ft) long, making it the largest known ichthyosaur specimen from the Lower Triassic.[27]

Skull[edit]

Like other ichthyosaurs, thesnoutofCymbospondylusis elongated into a long, conicalrostrum,the largest bones of which are thepremaxillaeandnasal bones.[65][5][10][20]The nasal bones also extend far back,[67][4][10]and, with the frontal bones, reach the anterior edge of thetemporal fenestrae.[5][10]The eye sockets areovaltoovoidin shape and are proportionally small in relation to the size of the skull.[65][4][5][10]The shape of the superior temporal fenestra differs between some species, being oval inC. nichollsiandC. duelferibut triangular inC. petrinus.[10]The number of bony elements constituting thesclerotic ringsvaries between species: 12 ossicles inC. duelferi;[10]13 ossicles inC. buchseri;[4]14 ossicles inC. nichollsi;[5]and between 14 and 18 ossicles inC. petrinus.[68]Although a sclerotic ring is preserved inC. youngorum,nothing has been said about the number of ossicles constituting it in the latter.[20]Thesagittal crestis more or less pronounced in the different species, being low inC. duelferiandC. nichollsi,clearly high inC. petrinus,[d][10]and totally absent inC. youngorum.[20]Theoccipital condyleofCymbospondylusis concave in shape.[5][10]Like other ichthyosaurs,Cymbospondylushas an elongated and thinlower jaw,[69]extending backwards to beyond the back of the skull.[5][10]The dentary, the main bone making up the lower jaw, extends almost to the level of the middle of the eye socket.[69][5][4][10]Thesurangularalso represents an important part of the mandible, and thins down to the retro-articularprocess.Theangular boneforms the ventral part of the lateral side of the lower jaw and contacts the surangular via a longsuture.[5][10][20]

ThedentitionofCymbospondylusis generallythecodont,meaning that the tooth roots are deeply cemented into the jawbone. However, not all species share the same robustness in terms of their dental implantation.C. petrinushas a particular form of thecodont dentition, its teeth appearing to be fused at the bottom of thealveoli.[70]C. duelferihas a subthecodont type of dentition, meaning that its teeth are implanted in shallow sockets.[10]C. youngorumhas a thick base of the bone attaching to the teeth,[11]a trait not seen in other ichthyosaurs.[20]The teeth arehomodont,that is to say they share an identical shape, being conical, ridged and pointed. The teeth also have longitudinal ridges that extend from the base of thecrownto the apical third.[10][20]The total number of teeth in the different species ofCymbospondylusis difficult to determine, because the state of preservation of certain fossils prevents formal evaluations from being obtained, being poorly preserved inC. buchseri,[4]and totally unknown inC. nichollsi.[5]Only three species were able to have a more or less clear estimate of their number of teeth:C. duelferihaving a number greater than 21 teeth known in the upper jaw, but unknown in the lower jaw;[20]C. petrinuswith between 30 and 35 teeth in the upper and lower jaws;[71]andC. youngorumhaving 43 teeth in the upper jaw and more than 31 teeth in the lower jaw.[20]

Classification[edit]

Phylogeny[edit]

The exact placement ofCymbospondyluswithin Ichthyosauria is poorly understood with its position varying between different studies, sometimes being recovered as more and sometimes as less derived than mixosaurids.[72]However it is agreed upon thatCymbospondylusis a rather basal member of the clade. Early phylogenies placedCymbospondyluswithinShastasauridae.[73]In the analysis of Bindelliniet al.(2021),Cymbospondylusis placed at the very base of Ichthyosauria, outside the more derived members of Hueneosauria (including Mixosauridae and Shastasauridae).[58]In the publication describingC. duelferi,Klein and colleagues recovered that all species from the Fossil Hill Member in Nevada form a clade with one another.[10]The description ofC. youngorumfurther supports this Nevadan clade, recoveringC. youngorumas its most derived member whileC. buchserifrom Europe sits at the base of the genus. Much like in the analysis by Bindellini and colleagues, shastasaurids and mixosaurids were recovered as more derived ichthyosaurs.[11]

Like in many analyses prior, the type species was not included in the dataset due to its questionable and fragmentary nature.[11]This causesCymbospondylusto have a very convoluted taxonomy, with it being suggested that the type species should be neglected.[5][10]The 2020 study reviewed the skull morphology ofC. nichollsiand found the species to be valid, as the skull morphology accords with that ofC. petrinusbut is distinct enough to be separate, such as the upper temporal fenestra shape being oval inC. nichollsibut triangular inC. petrinus.In their phylogenetic analysis the authors did not recover a definite placement forC. buchseri,leading them to state that further study was needed to determine whether the Swiss species belonged to the genus.[10]

The followingcladogramshows the position ofCymbospondyluswithin the Ichthyosauria after Sanderet al.,(2021):[11][20]

| Ichthyosauromorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolution[edit]

Ichthyosaurs form one of the major groups of marine reptiles that flourished during a large part of theMesozoic,between approximately 248 and 90 million years ago, i.e. during the end of the Lower Triassic until approximately the beginning of the Upper Cretaceous.[59]Appearing in the early temporal stages of this group,Cymbospondylusis therefore one of the oldest representatives to have been identified to date. However, despite its age, the genus shows that certain ichthyosaurs adopted a rapid increase in size throughout theirevolution.Indeed, the oldest known representatives ofichthyosauriforms(a group that includes ichthyosaurs, their ancestors and related lineages), such asCartorhynchus,have a skull measuring 5.5 centimeters (0.18 ft) long, while the largest known species ofCymbospondylus,C. youngorum,has a skull up to about 2 meters (6.6 ft) long, and yet these two taxa are only separated by about 2.5 million years. To compare with the evolution of a group of similartetrapods,namely thecetaceans,betweenPakicetus,which has a skull width of 12.7 centimeters (0.42 ft), andBasilosaurus,to which the latter has a skull width of 60 centimeters (2.0 ft), between 10 and 14 million years ago. A similar case is also observed in the subgroup ofodontocetes,because betweenSimocetus,which has a skull wide of 23.8 centimeters (0.78 ft), andLivyatan,which has a skull wide of approximately 2 meters (6.6 ft), approximately more than 25 million years ago. This rapid increase in size among ichthyosaurs could have been favored by the rapid diversification ofconodontsandammonitesafter thePermian–Triassic extinction event.The evolution of large eyes would subsequently have considerably reduced the large measurements in ichthyosaurs, because they helped better identify their source of food.[11]

Palaeobiology[edit]

Massare & Callaway (1990) propose that many Triassic ichthyosaurs includingCymbospondylusmay have been ambush predators. They argue that the long neck and torso would create drag in water while the laterally-flattened tail lacking the lunate fluke of later ichthyosaur taxa was more suited for an undulating swimming style. In their research they suggest that the elongated flexible bodies of early ichthyosaurs were built to support an undulating swimming style while the powerful tail would provide bursts of speed, both of which they cite as being possible adaptations to ambush prey. Massare & Callaway put this in contrast with Jurassic taxa, known for their compact, dolphin-like bodies adapted for more continuous swimming favorable to pursuit predators.[74]A strikingly similar bauplan was later obtained by two other large bodied marine amniote groups,mosasaursandarchaeocete whales.

Direct evidence for its diet exists for the medium-sizedCymbospondylus buchserifromSwitzerland,which was found with its stomach contents exclusively consisting ofhooksbelonging to soft-bodiedcoleoid cephalopods.However, this does not exclude the possibility thatC. buchsericould have taken larger prey, as its last meal may not reflect its typical diet accurately. Bindellini and colleagues suggest thatC. buchserimay have employed a more forceful feeding strategy with a slower feeding cycle and a higher biteforce, supported by the animal's robust rostrum. In theBesano Formation,Cymbospondyluswould have coexisted with two other smaller ichthyosaurs, the more gracile skulledBesanosaurusand smallmixosaurs.Whether or notC. buchseriwould have gone after large vertebrate prey, all three taxa display clear adaptations for different hunting strategies and prey preferences, however the details of their ecologies are not yet fully understood.[58]

ForC. youngoruma generalist diet of squid and fish is inferred based on the blunt and conical teeth in combination with the elongated rostrum. However, as withC. buchseri,Sanderet al.entertain the possibility thatC. youngorumcould have fed on large-bodied vertebrates as well, including the otherCymbospondylusspecies of the region.[11]

Bindellini and colleagues notes that shastasaurid diversity may have profited from the extinction ofCymbospondylus,such as theCarnianof China, known to have supported three ecologically different shastasaurids but no examples of cymbospondylids, which had gone extinct by that time.[58]

Reproduction[edit]

The holotype ofC. duelferipreserves three small strings of articulated vertebrae located within the trunk region of the specimen.[10]These vertebrae, which are only a third the size of the adult specimen, have been interpreted to represent the remains of three fetuses, with one specimen specifically facing towards the rear end of the putative mother. Following this interpretation,Cymbospondyluswould have given live birth to a minimum of three offspring.[citation needed]

Paleoecology[edit]

North America[edit]

All North American species ofCymbospondylusare known from fossils found in two geologic formations in theStar Peak Group,located in Nevada.C. petrinus,C. nichollsi,C. duelferiandC. youngorumare known from theFavret Formation,but the first named species is the only known representative of the genus who have been identified in thePrida Formation.[5][10][11]These two formations are linked by a singlemember,known as theFossil Hill Member.In the Prida Formation, this member outcrops west of the Humboldt Range, and extends to the Favret Formation, outcropping the Augusta Mountains,[75]where it reaches up to more than 300 m wide.[10][20]Although they are neighbors, the two formations do not share precisely the same age, the Prida one dating from the MiddleAnisian,while Favret dates from the Late Anisian,[10]between approximately 244 and 242 million years ago.[20]

The significant presence of marine reptiles,ammonitesand otherinvertebratesin theFossil Hill Memberindicates that the surface waters were well aerated,[76]but there is however little animal presence in thebenthiczones, with the notable exception ofbivalvesof the Halobiidae family. The fossils found show that the rock unit was once a pelagic ecosystem with a stable food web.Bony fishare little known and have currently only been discovered in the Favret Formation. Among the fish discovered, we find theactinopterygiansSaurichthysand an undetermined representative,[77]while among thesarcopterygians,numerous specimens of indeterminatecoelacanthidsare known.[20]In the Prida Formation, a significant number ofcartilaginous fisheshave been identified. These include thehybodontiforms,onesynechodontiform,and problematically positionedelasmobranchians.[78]The most abundantmarine reptilesof the Fossil Hill Member are the ichthyosaurs, includingCymbospondylusitself,Omphalosaurus,Phalarodonand the largeThalattoarchon.Few other marine reptiles are known from the Fossil Hill Member, the only clearly identified being thesauropterygianAugustasaurus.[11][20][79][22]

Europe[edit]

The only currently known specimen ofC. buschseriis recorded from theBesano Formation,also known as the Grenzbitumenzone in Switzerland. This formation is located in theAlpsand extends from southern Switzerland to northern Italy, containing numerous fossils dating from between the end of the Anisian and the beginning of theLadinian.[4][58]This formation is one of a series of Middle Triassic units atop acarbonate platformat Monte San Giorgio, and measures 5–16 metres (16–52 ft) thick. During the time when the animal lived, when the Besano Formation was being deposited, the region where Monte San Giorgio is would have been a marinelagoon,located in a basin on the western side of theTethys Ocean.[80][58]Researchers estimate that this same lagoon would have reached between 30–130 metres (98–427 ft) deep.[58]The near-surface waters would have been well oxygenated and were inhabited by a wide range ofplanktonandfree-swimmingorganisms.[80][81][82]However, water circulation within the lagoon was poor, resulting in typicallyanoxic waterat the bottom, deprived of oxygen.[81][82]The lagoon bottom would have been quite calm, as evidenced by the fine lamination of the rocks, and there is little evidence ofbottom-dwelling organisms modifying the sediment.[58]The presence of terrestrial fossils, such asconifersand land-dwelling reptiles indicates that the region would have been near land.[81]

Among the most common of the invertebrates from the Besano Formation is the bivalveDaonella.[83]Manygastropodsare known from the Besano Formation; predominantly those that could have lived as plankton or on algae.[82]Cephalopods present includenautiloids,coleoids,and the especially common ammonites.[83]The coleoids from the Besano Formation are not particularly diverse, but this may be due to their remains not readily fossilizing, with many of their known remains being preserved as stomach contents within the bodies of ichthyosaurs.[58][83]Arthropodsknown from the formation includeostracods,thylacocephalans,andshrimp.Other, rarer invertebrate groups known from the formation includebrachiopodsandechinoids,which lived on the seabed.[83][81]Radiolariansandmacroalgaeare also known in the formation, though the latter may have been washed in from elsewhere, as with many otherbottom-dwelling organisms.[83]A very large number of bony fish have been recorded in this formation.[83][84][85]Many bony fish have been recorded in this formation, with actinopterygians being quite diverse, including abundant small species as well as larger representatives likeSaurichthys.[84]Among the sarcopterygians, the number is more limited with in particularRieppelia,Ticinepomisand possiblyHolophagus,which are allcoelacanthiforms.[85]cartilaginous fishesof the Besano Formation are uncommon as well and mainly consist ofhybodonts.[83][86]

Unlike theFossil Hill Memberin Nevada, ichthyosaurs do not represent the most diverse marine reptiles in the Besano Formation, the latter being limited only toBesanosaurus,C. buchseri,PhalarodonandMixosaurus,[87]their abundance in the middle part of this zone correlating with the time when the lagoon was deepest.[58]Conversely, the sauropterygians represent the largest part of the assemblage of marine reptiles of this formation. Among these are theshell-crushingplacodontsParaplacodusandCyamodus.[88]as well aspachypleurosaursandnothosaurids.The pachypleurosaurOdoiporosaurusis known from the middle Besano Formation, while the particularly abundantSerpianosaurusdid not appear until the upper portion of the formation, where ichthyosaurs are becoming rarer.[83][89]Nothosaurids include the generaSilvestrosaurusandNothosaurus,the latter notably includingN. giganteusand possiblyN. juvenilis.[90]While rare,N. giganteusmay have been an apex predator likeC. buschseri.[58]Apart from ichthyosaurs and sauropterygians, other marine reptiles include the long-neckedTanystropheusandMacrocnemus,[91]and thethalattosauriansAskeptosaurus,ClaraziaandHescheleria.[92]

Niche partitioning[edit]

In both theFossil Hill Memberand the Besano Formation,Cymbospondylusis one of a variety of ichthyosaurs. The different species known would have had different feeding strategies toavoid competition.[11][20][58]Due to its large and sharp teeth,Thalattoarchonwould probably have been the onlyapex predatorwith whichCymbospondyluswas contemporary, probably attacking smaller marine reptiles, or even juveniles.[11][20][79][22]Besanosauruswould likely have specialized in feeding on coleoids, based on the shape and small size of its teeth. The stomach contents ofMixosaurus cornalianusshow the remains of small coleoids and fish, suggesting that it would have gone after smaller prey than its larger relatives.[58]The rarer mixosauridsMixosaurus kuhnschnyderiandPhalarodonboth possess broad crushing teeth.M. kuhnschnyderiis understood to have consumed coleoids, while the larger teeth ofPhalarodonmay have been suited for crushing prey items with external shells.[87][20]Omphalosauruswas probably abulk feederspecialized in grinding up ammonites.[20]

Notable appearances in media[edit]

ACymbospondylusis present in the 2003BBCdocufictionSea Monsters,and more precisely in a sequence featuring variousmarine reptilesof the Triassic. In the only scene in which he appears, the latter grabs by surprise a torn tail of aTanystropheus,until then held byNigel Marven,before the animal appears threatening towards the presenter.[93][94]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Leidy gives a slightly different description of the holotype in his 1868 paper, stating that it had only four dorsal vertebrae, due to the preservation of the fossil block.[1]

- ^This specimen is one of the several additionalC. petrinusfossils described by Meriam in 1908.[19]

- ^Sander and colleagues estimate animal size based on the 95 %prediction intervalinC. youngorum.Two additional estimates were also made by the team. The prediction interval less than 95 % gives a length of 12.5 m (41 ft) for a weight of 14.7 metric tons (16.2 short tons), while that which is greater than 95 % gives a length of 25 m (82 ft) for a weight of 135.8 metric tons (149.7 short tons).[11]As estimates do not come close to 95 %, these measurements are not considered to be the probable maximum sizes ofC. youngorum.[20]

- ^These observations differ according to certain specimens ofC. petrinus,because this distinction of the sagittal crest is clearer in the skull of specimen UCMP 9950 than in specimen UCMP 9913.[10]

References[edit]

- ^abcdeJoseph Leidy (1868)."Notice of some reptilian remains from Nevada".Proceedings of the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences.20:177–178.

- ^abcMerriam 1902,p. 104.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 123.

- ^abcdefghijklmnoP. Martin Sander (1989)."The large ichthyosaurCymbospondylus buchseri,sp. nov., from the Middle Triassic of Monte San Giorgio (Switzerland), with a survey of the genus in Europe ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.9(2): 163–173.Bibcode:1989JVPal...9..163S.doi:10.1080/02724634.1989.10011750.JSTOR4523251.S2CID128403865.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzNadia Fröbisch; P. Martin Sander; Olivier Rieppel (2006)."A new species ofCymbospondylus(Diapsida, Ichthyosauria) from the Middle Triassic of Nevada and a re-evaluation of the skull osteology of the genus ".Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.147(4): 515–538.doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00225.x.S2CID84720049.

- ^abcd"Cymbospondylus".Paleofile.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 5-6.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 65-70, 104-122.

- ^abMichael W. Maisch; Andreas T. Matzke (2004)."Observations on Triassic ichthyosaurs. Part XIII: New data on the cranial osteology ofCymbospondylus petrinus(LEIDY, 1868) from the Middle Triassic Prida Formation of Nevada ".Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Monatshefte.2004(6): 370–384.doi:10.1127/njgpm/2004/2004/370.S2CID221243435.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeNicole Klein; Lars Schmitz; Tanja Wintrich; P. Martin Sander (2020)."A new cymbospondylid ichthyosaur (Ichthyosauria) from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of the Augusta Mountains, Nevada, USA".Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.18(14): 1167–1191.Bibcode:2020JSPal..18.1167K.doi:10.1080/14772019.2020.1748132.S2CID219078178.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrP. Martin Sander; Eva Maria Griebeler; Nicole Klein; Jorge Velez Juarbe; Tanja Wintrich; Liam J. Revell; Lars Schmitz (2021)."Early giant reveals faster evolution of large body size in ichthyosaurs than in cetaceans".Science.374(6575): eabf5787.doi:10.1126/science.abf5787.PMID34941418.S2CID245444783.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 123-124.

- ^McGowan & Motani 2003,p. 65-66.

- ^Wolniewicz 2017,p. 123.

- ^International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (2012)."Article 8. What constitutes published work".International Code of Zoological Nomenclature(4th ed.).Retrieved16 July2021.

- ^Mike Taylor (8 June 2010)."Notes on Early Mesozoic Theropodsand the future of zoological nomenclature ".Sauropod Vertebra Picture of the Week.Archived fromthe originalon 9 March 2021.

- ^Bernhard Peyer (1944). "Die Reptilien vom Monte San Giorgio" [The reptiles of Monte San Giorgio].Neujahrsblau der Naturforschcnden Gesellschaft in Zürich(in German).146:1–95.

- ^Emil Kuhn-Schnyder (1964). "Die Wirbellierfauna der Tessiner Kalkalpen" [The vertebrate fauna of the Ticino Limestone Alps].Geologische Rundschau(in German).53:393–412.doi:10.1007/BF02040759.S2CID129726404.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 105-110.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyP. Martin Sander; Eva Maria Griebeler; Lars Schmitz (2021)."Supplementary Materials for Early giant reveals faster evolution of large body size in ichthyosaurs than in cetaceans"(PDF).Science.374(6575): eabf5787.doi:10.1126/science.abf5787.PMID34941418.

- ^Wolniewicz 2017,p. 149.

- ^abcNadia B. Fröbisch; Jörg Fröbisch; P. Martin Sander; Lars Schmitz; Olivier Rieppel (2013)."Supporting Information"(PDF).Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.110(4): 1393–1397.Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1393F.doi:10.1073/pnas.1216750110.PMC3557033.PMID23297200.

- ^Alexandra Houssaye; Yasuhisa Nakajima; P. Martin Sander (2018)."Structural, functional, and physiological signals in ichthyosaur vertebral centrum microanatomy and histology".Geodiversitas.40(2): 161–170.doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2018v40a7.S2CID56134834.

- ^abLene Liebe Delsett; Nicholas D. Pyenson (2021). "Early and fast rise of Mesozoic ocean giants".Science.374(6575): 1554–1555.Bibcode:2021Sci...374.1554D.doi:10.1126/science.abm3751.PMID34941421.S2CID245456946.

- ^abcJudy A. Massare; Jack M. Callaway (1994). "Cymbospondylus(Ichthyosauria: Shastasauridae) from the Lower Triassic Thaynes Formation of southeastern Idaho ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.14(1): 139–141.Bibcode:1994JVPal..14..139M.doi:10.1080/02724634.1994.10011545.JSTOR4523552.S2CID129916464.

- ^abcVictoria S. Engelschiøn; Lene L. Delsett; Aubrey J. Roberts; Jørn H. Hurum (2018)."Large-sized ichthyosaurs from the Lower Saurian niveau of the Vikinghøgda Formation (Early Triassic), Marmierfjellet, Spitsbergen".Norwegian Journal of Geology.98(2): 239–265.doi:10.17850/njg98-2-05.hdl:10852/71102.S2CID135275680.

- ^abcdefghijP. Martin Sander; René Dederichs; Tanja Schaaf; Eva Maria Griebeler (2024)."Cymbospondylus(Ichthyopterygia) from the Early Triassic of Svalbard and the early evolution of large body size in ichthyosaurs ".PalZ.98(2): 275–290.Bibcode:2024PalZ...98..275S.doi:10.1007/s12542-023-00677-3.S2CID269252902.

- ^Emil Kuhn-Schnyder (1980)."Über Reste eines großen Ichthyosauriers aus den Buchensteiner Schichten (ladinische Stufe der Trias) der Seceda (NE St. Ulrich/Ortisei, Prov. Bozen, Italien)"[About the remains of a large ichthyosaur from the Buchenstein layers (Ladin stage of the Triassic) of the Seceda (NE St. Ulrich/Ortisei, Prov. Bozen, Italy)](PDF).Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien(in German).83:231–244.

- ^abcdMarco Balini; Silvio C. Renesto (2012)."Cymbospondylusvertebrae (Ichthyosauria, Shastasauridae) from the Upper Anisian Prezzo Limestone (Middle Triassic, Southern Alps) with an overview of the chronostratigraphic distribution of the group ".Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia.118(1): 155–172.doi:10.13130/2039-4942/5996.S2CID131606349.

- ^P. Martin Sander (1992)."Cymbospondylus(Shastasauridae: Ichthyosauria) from the Middle Triassic of Spitsbergen: filling a paleobiogeographic gap ".Journal of Paleontology.66(2): 332–337.Bibcode:1992JPal...66..332S.doi:10.1017/S0022336000033825.JSTOR1305917.S2CID132741980.

- ^Olivier Rieppel; Fabio Marco Dalla Vecchia (2001)."Marine reptiles from the Triassic of the Tre Venezie Area, Northeastern Italy".Fieldiana, Geology.New Series.44:1–25.

- ^abErin E. Maxwell; Benjamin P. Kear (2013)."Triassic ichthyopterygian assemblages of the Svalbard archipelago: A reassessment of taxonomy and distribution".GFF.135(1): 85–94.Bibcode:2013GFF...135...85M.doi:10.1080/11035897.2012.759145.S2CID129092001.

- ^Merriam 1902,p. 106-107.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 104.

- ^John W. Hulke (1873)."Memorandum on some fossil vertebrate remains collected by the Swedish expeditions to Spitzbergen in 1864 and 1868".Bihang till Kongliga Svenska Vetenskaps-Akademiens Handlingar.1(9): 1–11.

- ^Nikolai N. Yakowlew (1902). "Neue funde von Trias-Sauriern auf Spitzbergen" [New discoveries of Triassic reptiles on Spitsbergen].Verhandlungen der Russisch-Kaiserlichen Mineralogischen Gesellschaft zu St. Petersburg(in German).40:179–202.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 149-150.

- ^Carl Wiman (1910)."Ichthyosaurier aus der Trias Spitzbergens"[Ichthyosaurs from the Triassic of Spitsbergen](PDF).Bulletin of the Geological Institutions of the University of Uppsala(in German).10:124–148.

- ^McGowan & Motani 2003,p. 128.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 124-127.

- ^McGowan & Motani 2003,p. 125.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 150-152.

- ^John C. Merriam (1911)."Notes on the relationships of the marine saurian fauna described from the Triassic of Spitzbergen by Wiman".University of California Publications. Bulletin of the Department of Geology.6(13): 317–327.

- ^Elizabeth L. Nicholls; Donald B. Brinkman; Jack M. Callaway (1999)."New Material ofPhalarodon(Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) from the Triassic of British Columbia and its Bearing on the Interrelationships of Mixosaurs ".Palaeontographica Abteilung A.252(1): 1–22.doi:10.1127/pala/252/1998/1.S2CID246923904.

- ^Lars Schmitz (2005). "The taxonomic status ofMixosaurus nordenskioeldii(Ichthyosauria) ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.25(4): 983–985.doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0983:TTSOMN]2.0.CO;2.JSTOR4524525.

- ^Friedrich von Huene (1916)."Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Ichthyosaurier im deutschen Muschelkalk"[Contributions to the knowledge of ichthyosaurs in the German Muschelkalk].Palaeontographica(in German).68:1–68.

- ^Von F. Broili (1916)."Einige Bemerkungen über die Mixosauridae"[Some remarks about the Mixosauridae].Anatomischer Anzeiger(in German).49:474–494.

- ^Jack M. Callaway; Judith A. Massare (1989). "Geographic and stratigraphic distribution of the Triassic Ichthyosauria (Reptilia; Diapsida)".Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen.178:37–58.doi:10.1127/njgpa/178/1989/37.

- ^McGowan & Motani 2003,p. 129.

- ^Chun Li; Hai-Lu You (2002)."Cymbospondylusfrom the Upper Triassic of Guizhou, China "(PDF).Vertebrata PalAsiatica(in Chinese and English).40:9–16.

- ^Qing-Hua Shang; Chun Li (2009)."On the occurrence of the ichthyosaurShastasaurusin the Guanling biota (Late Triassic), Guizhou, China "(PDF).Vertebrata PalAsiatica(in Chinese and English).47(3): 178–193.

- ^Maisch 2010,p. 163.

- ^P. Martin Sander; Xiaohong Chen; Long Cheng; Xiaofeng Wang (2011)."Short-Snouted Toothless Ichthyosaur from China Suggests Late Triassic Diversification of Suction Feeding Ichthyosaurs".PLOS ONE.6(5): e19480.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...619480S.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019480.PMC3100301.PMID21625429.

- ^Qing-Hua Shang; Chun Li (2013)."On the sexual dimorphism ofShastasaurus tangae(Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) from the Triassic Guanling Biota, China "(PDF).Vertebrata PalAsiatica(in Chinese and English).51(4): 253–264.

- ^Cheng Ji; Da-Yong Jiang; Ryosuke Motani; Olivier Rieppel; Wei-Cheng Hao; Zuo-Yu Sun (2016)."Phylogeny of the Ichthyopterygia incorporating recent discoveries from South China".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.36(1): e1025956.Bibcode:2016JVPal..36E5956J.doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1025956.S2CID85621052.

- ^Benjamin C. Moon (2019)."A new phylogeny of ichthyosaurs (Reptilia: Diapsida)"(PDF).Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.17(2): 129–155.Bibcode:2019JSPal..17..129M.doi:10.1080/14772019.2017.1394922.hdl:1983/463e9f78-10b7-4262-9643-0454b4aa7763.S2CID90912678.

- ^Da-Yong Jiang; Ryosuke Motani; Andrea Tintori; Olivier Rieppel; Cheng Ji; Min Zhou; Xue Wang; Hao Lu; Zhi-Guang Li (2020)."Evidence supporting predation of 4-m marine reptile by Triassic megapredator".iScience.23(9): 101347.Bibcode:2020iSci...23j1347J.doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101347.PMC7520894.PMID32822565.

- ^abcdefghijklmnGabriele Bindellini; Andrzej S. Wolniewicz; Feiko Miedema; Torsten M. Scheyer; Cristiano Dal Sasso (2021)."Cranial anatomy ofBesanosaurus leptorhynchusDal Sasso & Pinna, 1996 (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) from the Middle Triassic Besano Formation of Monte San Giorgio, Italy/Switzerland: taxonomic and palaeobiological implications ".PeerJ.9:e11179.doi:10.7717/peerj.11179.PMC8106916.PMID33996277.

- ^abRyan Marek (2015)."Fossil Focus: Ichthyosaurs".Palaeontology Online.5:8.Archivedfrom the original on 18 January 2021.Retrieved13 June2020.

- ^P. Martin Sander (2000)."Ichthyosauria: their diversity, distribution, and phylogeny".Paläontologische Zeitschrift.74(1): 1–35.Bibcode:2000PalZ...74....1S.doi:10.1007/BF02987949.S2CID85352593.

- ^Ryosuke Motani (2005)."Evolution of Fish-Shaped Reptiles (reptilia: Ichthyopterygia) in Their Physical Environments and Constraints"(PDF).Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences.33:395–420.Bibcode:2005AREPS..33..395M.doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.33.092203.122707.S2CID54742104.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 23 December 2018.

- ^Judith M. Pardo-Pérez; Benjamin P. Kear; Erin E. Maxwell (2020)."Skeletal pathologies track body plan evolution in ichthyosaurs".Scientific Reports.10(1): 4206.Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.4206P.doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61070-7.PMC7060314.PMID32144303.

- ^Johan Lindgren; Peter Sjövall; Ryan M. Carney; Per Uvdal; Johan A. Gren; Gareth Dyke; Bo Pagh Schultz; Matthew D. Shawkey; Kenneth R. Barnes; Michael J. Polcyn (2014). "Skin pigmentation provides evidence of convergent melanism in extinct marine reptiles".Nature.506(7489): 484–488.Bibcode:2014Natur.506..484L.doi:10.1038/nature12899.PMID24402224.S2CID4468035.

- ^McGowan & Motani 2003,p. 66.

- ^abcMerriam 1908,p. 105.

- ^Dean R. Lomax; Paul de la Salle; Marcello Perillo; Justin Reynolds; Ruby Reynolds; James F. Waldron (2024)."The last giants: New evidence for giant Late Triassic (Rhaetian) ichthyosaurs from the UK".PLOS ONE.19(4): e0300289.Bibcode:2024PLoSO..1900289L.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0300289.PMC11023487.PMID38630678.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 106.

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 107.

- ^abMerriam 1908,p. 110.

- ^Ryosuke Motani (1997), "Temporal and Spatial Distribution of Tooth Implantations in Ichthyosaurs", in Callaway, Jack M.; Nicholls, Elizabeth L. (eds.),Ancient Marine Reptiles,San Diego:Academic Press,pp. 81–103,doi:10.1016/B978-012155210-7/50007-7,ISBN978-0-12-155210-7,S2CID139029769

- ^Merriam 1908,p. 111.

- ^Maisch 2010,p. 155.

- ^Ryosuke Motani (1999)."Phylogeny of the Ichthyopterygia"(PDF).Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.19(3): 472–495.Bibcode:1999JVPal..19..473M.doi:10.1080/02724634.1999.10011160.JSTOR4524011.S2CID84536507.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 5 March 2016.Retrieved19 October2011.

- ^Massare, J.A.; Callaway, JM (1990)."The affinities and ecology of Triassic ichthyosaurs".Geological Society of America Bulletin.102(4): 409–416.Bibcode:1990GSAB..102..409M.doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1990)102<0409:TAAEOT>2.3.CO;2.

- ^Nichols & Silberling 1977,p. 20.

- ^Nichols & Silberling 1977,p. 18.

- ^P. Martin Sander; Olivier C. Rieppel; H. Bucher (1994). "New Marine Vertebrate Fauna from the Middle Triassic of Nevada".Journal of Paleontology.68(3): 676–680.Bibcode:1994JPal...68..676S.doi:10.1017/S0022336000026020.JSTOR1306213.S2CID133180790.

- ^Gilles Cuny; Olivier Rieppel; P. Martin Sander (2001)."The shark fauna from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of North-Western Nevada".Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.133(3): 285–301.doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2001.tb00627.x.S2CID86253330.

- ^abNadia B. Fröbisch; Jörg Fröbisch; P. Martin Sander; Lars Schmitz; Olivier Rieppel (2013)."Macropredatory ichthyosaur from the Middle Triassic and the origin of modern trophic networks".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.110(4): 1393–1397.Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1393F.doi:10.1073/pnas.1216750110.PMC3557033.PMID23297200.

- ^abSilvio Renesto; Cristiano Dal Sasso; Fabio Fogliazza; Cinzia Ragni (2020)."New findings reveal that the Middle Triassic ichthyosaurMixosaurus cornalianusis the oldest amniote with a dorsal fin ".Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.65(3): 511–522.doi:10.4202/app.00731.2020.S2CID222285117.

- ^abcdHeinz Furrer (1995)."The Kalkschieferzone (Upper Meride Limestone, Ladinian) near Meride (Canton Ticino, Southern Switzerland) and the evolution of a Middle Triassic intraplatform basin".Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae.88(3): 827–852.

- ^abcVittorio Pieroni; Heinz Furrer (2020)."Middle Triassic gastropods from the Besano Formation of Monte San Giorgio, Switzerland".Swiss Journal of Palaeontology.139(1): 2.Bibcode:2020SwJP..139....2P.doi:10.1186/s13358-019-00201-8.ISSN1664-2384.S2CID211089125.

- ^abcdefghHans-Joachim Röhl; Annette Schmid-Röhl; Heinz Furrer; Andreas Frimmel; Wolfgang Oschmann; Lorenz Schwark (2001)."Microfacies, geochemistry and palaeoecology of the Middle Triassic Grenzbitumenzone from Monte San Giorgio (Canton Ticino, Switzerland)".Geologia Insubrica.6:1–13.

- ^abCarlo Romano (2021)."A Hiatus Obscures the Early Evolution of Modern Lineages of Bony Fishes".Frontiers in Earth Science.8:618853.doi:10.3389/feart.2020.618853.ISSN2296-6463.S2CID231713997.

- ^abChristophe Ferrante; Lionel Cavin (2023)."Early Mesozoic burst of morphological disparity in the slow-evolving coelacanth fish lineage".Scientific Reports.13(1): 11356.Bibcode:2023NatSR..1311356F.doi:10.1038/s41598-023-37849-9.PMC10345187.PMID37443368.

- ^John G. Maisey (2011)."The braincase of the Middle Triassic sharkAcronemus tuberculatus(Bassani, 1886) ".Palaeontology.54(2): 417–428.Bibcode:2011Palgy..54..417M.doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01035.x.S2CID140697673.

- ^abWinand Brinkmann (2004)."Mixosaurier (Reptilia, Ichthyosaurier) mit Quetschzähnen aus der Grenzbitumenzone (Mitteltrias) des Monte San Giorgio (Schweiz, Kanton Tessin)"[Mixosaurs (Reptilia, Ichthyosauria) with crushing teeth from the Grenzbitumenzone (Middle Triassic) of Monte San Giorgio (Switzerland, Canton of Ticino)].Schweizerische Paläontologische Abhandlungen(in English and German).124:1–86.

- ^Michael W. Maisch (2020)."The evolution of the temporal region of placodonts (Diapsida: Placodontia) – a problematic issue of cranial osteology in fossil marine reptiles".Palaeodiversity.13(1): 57–68.doi:10.18476/pale.v13.a6.S2CID218963106.

- ^Nicole Klein; Heinz Furrer; Iris Ehrbar; Marta Torres Ladeira; Henning Richter; Torsten M. Scheyer (2022)."A new pachypleurosaur from the Early Ladinian Prosanto Formation in the Eastern Alps of Switzerland".Swiss Journal of Palaeontology.141(1): 12.Bibcode:2022SwJP..141...12K.doi:10.1186/s13358-022-00254-2.PMC9276568.PMID35844249.S2CID250460492.

- ^Silvio Renesto (2010)."A new specimen ofNothosaurusfrom the latest Anisian (Middle Triassic) Besano formation (Grenzbitumenzone) of Italy ".Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia.116(2): 145–160.doi:10.13130/2039-4942/5946.S2CID86049393.

- ^Stephan N.F. Spiekman; James M. Neenan; Nicholas C. Fraser; Vincent Fernandez; Olivier Rieppel; Stefania Nosotti; Torsten M. Scheyer (2020)."The cranial morphology ofTanystropheus hydroides(Tanystropheidae, Archosauromorpha) as revealed by synchrotron microtomography ".PeerJ.8:e10299.doi:10.7717/peerj.10299.PMC7682440.PMID33240633.

- ^Nicole Klein; P. Martin Sander; Jun Liu; Patrick S. Druckenmiller; Eric T. Metz; Neil P. Kelley; Torsten M. Scheyer (2023)."Comparative bone histology of two thalattosaurians (Diapsida: Thalattosauria):Askeptosaurus italicusfrom the Alpine Triassic (Middle Triassic) and a Thalattosauroidea indet. from the Carnian of Oregon (Late Triassic) ".Swiss Journal of Palaeontology.142(1): 15.Bibcode:2023SwJP..142...15K.doi:10.1186/s13358-023-00277-3.PMC10432342.PMID37601161.

- ^Nigel Marven; Jasper James (2004).Chased by Sea Monsters: Prehistoric Predators of the Deep.New York:DK.pp. 74–79.ISBN978-0-7566-0375-5.OCLC1391299004.

- ^Tim Haines; Paul Chambers (2006).The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life.Buffalo, New York:Firefly Books. p. 65.ISBN1-55407-125-9.

Bibliography[edit]

- Merriam, John C.(1902)."Triassic Ichthyopterygia from California and Nevada".University of California Publications. Bulletin of the Department of Geology.3:63–108.

- Merriam, John C.(1908).Triassic Ichthyosauria, with special reference to the American forms.Memoirs of the University of California. Vol. 1.Berkeley, California:The University Press. pp. 1–196.OCLC457714430.

- Nichols, Kathryn M.; Silberling, Norman J. (1977).Stratigraphy and depositional history of the Star Peak Group (Triassic), northwestern Nevada.Vol. 175–178.Boulder:Geological Society of America, Special Papers.pp. 1–73.doi:10.1130/SPE178-p1.ISBN978-0-813-72178-1.S2CID129115608.

- Maisch, Michael W.; Matzke, Andreas T. (2000)."The Ichthyosauria".Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B.298:1–159.

- McGowan, Christopher; Motani, Ryosuke (2003).Handbook of Paleoherpetology Part 8: Ichthyopterygia.Vol. 1.Munich:Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 1–175.ISBN978-3-899-37007-2.OCLC469848769.

- Maisch, Michael W. (2010)."Phylogeny, systematics, and origin of the Ichthyosauria – the state of the art"(PDF).Palaeodiversity.3:151–214.

- Wolniewicz, Andrzej S. (2017).The Anatomy, Taxonomy and Systematics of Middle Triassic–Early Jurassic Ichthyosaurs (Reptilia: Ichthyopterygia) and the Phylogeny of Ichthyopterygia(PhD).University of Oxford.

External links[edit]

- Paleontological videos

- Moore, Kallie (22 March 2022)."The Sudden Rise of the First Colossal Animal".PBS Eons.Archivedfrom the original on 2 November 2023 – viaYouTube.