Chu (Taoism)

| Chu | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

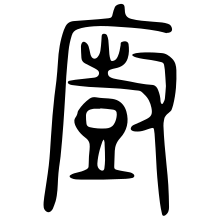

Ancient Chineseseal scriptforchuTrù "kitchen" | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Trù | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Trù | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | kitchen | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 주 | ||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | Trù | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | Trù | ||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | ちゅう | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Part ofa serieson |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

Chu(Trù,lit. 'kitchen') is aDaoistname used for various religious practices including communalchu(Kitchen) banquet rituals inWay of the Celestial Mastersliturgy, the legendaryxingchu( hành trù, Mobile Kitchen) associated with Daoistxian( "transcendents; 'immortals'" ), andwuchu( ngũ trù, Five Kitchens) representing thewuzang( ngũ tạng, Five Viscera) inneidanmeditation techniques.

Terminology

[edit]Chú( "kitchen; to cook; a cook" ) can be written with threeChinese charactersTrù, 㕑, and trù. The commontraditional Chinese characterTrùcombines the"house radical"Quảngwith a phonetic indicatorshù尌(joiningzhù壴"drum" andcùnThốn"hand" ); and thevarianttraditional character㕑has"cliff radical"Háninstead of quảng. Thesimplified Chinese characterTrùomits theSĩelement in 壴, leading to a "graphicfolk etymology"of" A hán 'room' for cookingĐậu'beans' with your thốn 'hands' ".[1]The ChineselogographTrù was anciently used as aloan characterforchúThụ(with the"wood radical"Mộc, "cabinet" ) orchúTrù("cloth radical"Cân, "a screen used for a temporary kitchen" ).

TheModern Standard Chineselexicon useschuin manycompound words,for instance,chúfáng(Trù phòngwith phòng "room", "kitchen" ),chúshī(Trù sưwith sư "master", "cook; chef" ),chúdāo(Trù đaowith đao "knife", "kitchen knife" ), andpáochú(Bào trùwith bào "kitchen", meaning "kitchen" ).

In Daoist specialized vocabulary,chunames a Kitchen-feast communal meal, and sometimes has a technical meaning of "magic", "used to designate the magical recipes through which one becomes invisible".[2]The extensivesemantic fieldofchucan be summarized in some key Daoist expressions: ritual banquets, communion with divinities, granaries (zangTàng, a word that also denotes the viscera), visualization of the Five Viscera (wuzangNgũ tạng, written with the"flesh radical"⺼), and abstention from cereals (bigu), and other food proscriptions.[3]According to Daoist classics, whenbigu"grain avoidance" techniques were successful,xingchu( hành trù, Mobile Kitchens ortianchu( thiên trù, Celestial Kitchens) were brought in gold and jade vessels by theyunü( ngọc nữ, Jade Women) andjintong( kim đồng, Golden Boys), associated with the legendaryJade Emperor.[4]

Chinese Buddhistterminology applieschu( trù, cf. Thụ "cabinet" ) "kitchen; kitchen cupboard" to denote the "cabinet for an image or relic of the Buddhas", translatingSanskritbhakta-śālā"food-hall" ormahânasa"kitchen".[5]

InChinese astronomy,Tiānchú( thiên trù, Celestial Kitchen) is the name of anasterismin the constellationDraco,located next toTiānbàng( thiên bang, CelestialFlail), andNèichú( nội trù, Inner Kitchen).

Translations

[edit]There is no standard English translation for either Daoistchu( trù, Kitchen) orxingchu( hành trù, Mobile Kitchen). The former is rendered as:

- "kitchen festival", "kitchen feast"[6]

- "Kitchens"[7]

- "kitchen banquets"[8]

- "cuisines"[9][10][11]

- "Kitchens"[12]

- "cuisines"[13]

TheseAnglophonescholars render Chinesechuas either Englishkitchen( "a room for preparing food" ), optionally clarified withK-,-festivalor -feast,orcuisine( "a characteristic style of cooking, often associated with a place of origin" ). The latter followsFrancophonesinologists, for instanceHenri Masperoand Christine Mollier, who accurately translated Chinesechuas Frenchcuisine( "kitchen; cooking" ) andxingchuascuisine de voyage( "travel kitchen" ).[14][15]Although Englishkitchenand Frenchcuisinearedoubletsderiving from Latincocīna( "cooking; kitchen" ), they arefalse friendswith significant semantic differences between Englishkitchenandcuisine.Chinese usually translates Englishkitchenas chúfáng (Trù phòng,"kitchen" ) andcuisineaspēngrèn(Phanh nhẫm,"art of cooking" ).

The termxingchu( hành trù ) has been translated as

- "Traveling Canteen"[16]

- "mobile kitchen"[17]

- "perform the Kitchen"[7]

- "travelling kitchen-feast"[18]

- "traveling canteen'[19]

- "traveling kitchen"[9]

- "movable cuisines"[4][11]

- "Mobile Kitchens"[12]

Joseph Needhamcalls Ware's "Traveling Canteen" a "bizarre translation".[20]While Maspero uniquely interprets thexing(Hành) inxingchuas a verb ( "to perform" ), the other scholars read it as a modifier ( "to go; to move" ) translated astraveling,mobile,ormovable(cf.movable feast). Thechunoun inxingchuis translated as Englishkitchen,cuisine,orcanteen.However, the latter ambiguous word has several meanings besidescanteen( "a cafeteria or snack bar provided by an organization" ),canteen( "a small water bottle" ), andBritish Englishcanteen( "a case or box containing a cutlery set" ). To further complicate translatingxingchu,travelling canteenwas the 18th-century equivalent of apicnic basket.In modern terms, thexingchuis comparable with amobile kitchen,[21]militaryfield kitchen,food truck,orfood cart.

ChuKitchen feast

[edit]Thechu( trù, Kitchen), also known asfushi( phúc thực, "good luck meal" ), was a religious banquet that usually involved preliminary fasting and purification before consuming a meal of vegetarian food andChinese wine.The banquet was hosted by families on the occasion of births and deaths, prepared for a ritually-fixed number of parishioners, and accompanied by specific ritual gifts to the Daoist priest. Although the Kitchen Feast became a regular element of organized Daoist religious traditions, scholars do not know the date when it was introduced into the liturgy. One early textual record is the c. 499Zhen'gaosaying that Xu Mi ( hứa mịch, 303–376) offered a Kitchen meal to five persons.[22]

These communalchuKitchen banquets have a pre-Daoist antecedent in popularChinese folk religion:the termchuwas anciently used for the ceremonial meals organized by communities to honor theshe( xã, God of the Soil). Although orthodox Daoists criticized, and sometimes banned, thesechuhui( trù hội, "cuisine congregations" ) for making immoral animal sacrifices, they nevertheless perpetuated the custom by adapting and codifying it.[3]Chukitchen-feasts have many features in common with another Daoist ritual meal, thezhāi( trai, "fast; purification; retreat" ), and the two are frequently treated as having the same functions. The 7th-century DaoistZhaijielu( trai giới lục, Records of Fasting) suggested thatzhaiwere anciently calledshehui( xã hội, "festival gatherings of the soil god" —now the modern Chinese word for "society" ), which was later changed intozhaihui( trai hội ).[23]

TheWay of the Celestial Mastersreligion, founded byZhang Daolingin 142 CE, celebratedchukitchen festivals at New Year and the annualsanhui( tam hội, Three Assemblies), which were major Daoist festivals held in the first, seventh, and tenth lunar months, when believers assembled at their local parish to report any births, deaths, or marriages, so that the population registers could be updated. Parishioners who had reason to celebrate on these occasions would host achufeast for other members of the community in proportion to the significance of their auspicious event and their means. Accounts of these banquets "emphasize both the sharing of food and the affirmation of the unique, religious merit-based social order of the Daoist community".[10]

Thechusacrament had three levels of banquets and ritual gifts, depending upon what the family was celebrating. For the birth of a boy, theshangchu( thượng trù, Superior Ceremony of the Kitchen) was a banquet offered to the priest and ten members of the parish, with gifts to the priest of a hundred sheets of paper, a pair ofink brushes,aninkstick,and an ink scraper. For the birth of a girl, it was the less expensivezhongchu( trung trù, Middle Ceremony of the Kitchen) with a banquet for five parishioners, and the gifts, which the parents had to provide within one month following the birth, were a mat, a wastebasket, and a broom. For the death of a family member, thexiachu( hạ trù, Inferior Ceremony of the Kitchen), also calledjiechu( giải trù, Kitchen of Deliverance), is not described in Daoist texts, and we only know that the rival Buddhist polemicists claimed it was a "great orgy".[2]

The anti-DaoistErjiaolun( nhị giáo luận, Essay on Two Religions) by the Buddhist monkDao'an(312–385) saidchukitchen-feasts were intended to bring aboutjiěchú( giải trừ, "liberation and elimination" ) from pollution and sins, which were connected with the soil god and tombs.[24]The parallel passage in the 6th-centuryBianhuolun( biện hoặc luận, Essay on Debating Doubts) uses the homophonousgraphic variantofjiěchú( giải trù, "liberation kitchen" ), thus connecting bothchú"kitchen" andchú"liberation" to non-Daoist gods of the soil.[25]

Daoist sources record that the people invited to achuKitchen feast would first observe a period of purification that included fasting and abstention from sex. Kitchen rituals lasted for one, three, or seven days. Participants consumed exclusively vegetarian food and moderate amounts of wine, which was considered as a mandatory element of the banquet.[3]For the Superior Kitchens fiveshengof wine (about a liter) per person was planned, for the Middle Kitchens, foursheng,and for the Inferior Kitchen three. The participants "must have departed a bit happy, but not drunk."[2]The leftovers were given to other parishioners who could thereby share in the ritual.

Besides annual festivals on fixed dates like the Three Assemblies,chuKitchen ceremonies were also performed in special circumstances, particularly when there was disease, sin, or death pollution. They were believed to have exorcistic and salvific powers and to confer good luck or merit upon the adepts.[3]Kitchen ceremonies often involved Daoist ritualjiao( tiếu, "offerings" ) of cakes and pieces of fabric in order to obtain particular favors, such as petitions for recovery from illnesses, prayers for rain in time of drought, and thanksgivings for favors received. An altar was laid out in the open air, and the priest recited prayers.[26]

Ge Hong's c. 318Baopuzi(see below) mentions profligately expensivechuKitchen Feasts in contrasting heterodoxyaodao( yêu đạo, "demonic cults" ), which involved sacrificing animals to gods who enjoyed their blood, with theLijia dao( lý gia đạo,Way of the Li Family).[27]The context praises the contemporary charlatan healer Li Kuan ( lý khoan ) for not following the ancient tradition of animal sacrifice, while blaming him for extravagance.

The more than a hundred ways for dealing with demons [ chư yêu đạo bách dư chủng ] all call for slaying living creatures so that their blood may be drunk. Only the doctrine of the Lis [ lý gia đạo ] is slightly different. Yet, though it does no butchering, whenever its "good-luck food" is served [ mỗi cung phúc thực ], it includes varieties of mixtures without limit. In planning the meal, one strives for sumptuousness, and the rarest things must be purchased. Several dozen may work in the kitchen [ hoặc sổ thập nhân trù ], and costs for food can run high indeed. In turn, these are not completely disinterested affairs, and they might well be classed with things to be forbidden.[28]

XingchuMobile Kitchen traditions

[edit]In Daoist hagiographies and stories, the esoteric ability to summon axingchu( hành trù, Mobile Kitchen) was a standardtropefor the powers of axiantranscendent. Thexingchu,which Campany called a "curious business",[29]was a sumptuous banquet of rare delicacies, exotic foods, and wines that could be instantly served up by spirits anywhere on command.

The tradition ofxingchu"meditational cuisines" or "contemplative cuisines" seems to have developed in a parallel and complementary manner to thechu"communal cuisine liturgy".[30]Xiantranscendents were portrayed as eschewing what counted in China as ordinary foods, especially grains (seebigu), and instead eating superior, longevity-inducing substitutes such as sesame seeds andlingzhimushrooms, typically found in distant and legendary places removed from the heartland of agriculture-based Chinese civilization. Transcendents were frequently depicted as winged beings able to fly long distances rapidly and summoning axingchubanquet at will eliminated the need to travel across the world and heavens in order to obtain rare foodstuffs of immortality.[31]

TheJin DynastyDaoist scholarGe Hongcompiled the two primary sources of information aboutxingchuMobile Kitchens, theBaopuziandShenxian zhuan.Ge portrayed adepts seekingxian-hood as avoiding ordinary food such as grains, instead eating "rare, exotic foodstuffs from the far reaches of the cosmos", marvelous products conveying the "numinous power" suggested by their peculiarity. "The ability to command at will a spirit-hosted serving of exotic food and drink in elegant vessels may seem trivial, but when one recalls that many Daoist scriptures prohibit the feasting on sacrificial meats and liquors enjoyed by the aristocracy, and that many adepts did their work on mountains and were isolated from agricultural communities and markets, the practice assumes a more serious aspect."[32]

Baopuzi

[edit]The c. 318 CE "Inner Chapters" of theBaopuzi(Master Who Embraces Simplicity) have nine occurrences of the wordxingchu( hành trù, Mobile Kitchen). Seven of them are in contexts of alchemical medicines and elixirs, most of which have poisonoustoxic heavy metalingredients. TheBaopuziuses two related verbs for beckoning a Mobile Kitchen:zhì( chí, "arrive at; reach; come" ) andzhì( trí, "cause to arrive at; get to; come to" ). The other twoxingchuusages are in proper names of a Daoistamuletand book, theXingchu fu( hành trù phù, Amulet of the Traveling Kitchen), and theXingchu jing( hành trù kinh, Scripture of the Traveling Kitchen). TheBaopuzialso lists another book titledRiyue chushi jing( nhật nguyệt trù thực kinh, Scripture of the Kitchen Meals of the Sun and the Moon).[33]

Three of the sevenBaopuzielixirs are said to have dual purpose usages, long-term consumption is said to grantxiantranscendence, including the ability to summonxingchu,and short-term consumption provides a panacea—specifically for eliminating theThree Corpsesor Three Worms, demons that live within the human body and hasten their host's death, and theNine Wormsor Nine Vermin, broadly meaning internal worms and parasites. First, theXian Menzi dan( tiện môn tử đan, Master Xian Men's Elixir) is prepared from wine and cinnabar. "After it has been taken for one day the Three Worms and all illnesses are immediately purged from the patient. If taken for three years, it will confer geniehood and one is sure to be served by two fairies, who can be employed to summon the Traveling Canteen [ khả dịch sử trí hành trù ]."[34]Second, a list of methods for eating and drinking realgar says, "In each case it confers Fullness of Life; all illnesses are banished; the Three Corpses drop from the body; scars disappear; gray hair tums black; and lost teeth are regenerated. After a thousand days, fairies [translatingyunuNgọc nữ Jade Maiden] will come to serve you and you can use them to summon the Traveling Canteen [ dĩ trí hành trù ]. "[35]Third, consuming pure, unadulteratedlacquerwill put a man in communication with the gods and let him Enjoy Fullness of Life. When eaten with pieces of crab in mica or jade water, "The Nine Insects will then drop from you, and the bad blood will leave you through nose-bleeds. After a year, the six-chiagods and the Traveling Canteen will come to you [ nhất niên lục giáp hành trù chí dã ]. "[36]Thisliujia( lục giáp, SixJiaGods) and theliuyin( lục âm, Six Yin) below refer toastrologicalDunjiadivination. An alternate translation is "the sixjiaand the traveling canteen will arrive ".[37]

The remaining fourBaopuziformulas are said to create stronger and more versatile elixirs. Fourth, theJiuguang dan( cửu quang đan, Ninefold Radiance Elixir) is made by processing certain unspecified ingredients with thewushi( ngũ thạch, Five Minerals, seeCold-Food Powder), i.e.,cinnabar,realgar,purifiedpotassium alum,laminarmalachite,andmagnetite.[38]Each mineral is put through five alchemical cycles and assumes five hues, so that altogether twenty-five hues result, each with specific powers, for example, the blue elixir will revive a recently deceased person. "If you wish to summon the Traveling Canteen [ dục trí hành trù ], smear your left hand with a solution of black elixir; whatever you ask for will be at your beck and call, and everything you mention will arrive without effort. You will be able to summon any thing or any creature in the world."[39]Fifth, theBaopuziquotes fromShennong sijing( thần nông tứ kinh,Shennong's Four Classics), "Medicines of the highest type put the human body at ease and protract life so that people ascend and become gods in heaven, soar up and down in the air, and have all the spirits at their service. Their bodies grow feathers and wings, and the Traveling Canteen comes whenever they wish [ hành trù lập chí ]."[40]Sixth, the method of Wu Chengzi ( vụ thành tử ) compounds alchemical gold from realgar, yellow sand, and mercury, and then forms it into small pills. Coating the pills with different substances will produce magical effects, for instance, if one is smeared with ram's blood and thrown into a stream, "the fish and the dragons will come out immediately, and it will be easy to catch them." And, "If it is coated with hare's blood and placed in a spot belonging to the Six Yin, the Traveling Canteen and the fairies will appear immediately and place themselves at your disposal [ hành trù ngọc nữ lập chí ], to a total of sixty or seventy individuals."[41]Seventh, Liu Gen ( lưu căn, or Liu Jun'an lưu quân an ), who Ware wrongly identifies as the Daoist prince and authorLiu An( lưu an ),[42]learned the art of metamorphosis from an alchemical text attributed to theMohistfounderMozi,theMozi wuxing ji( mặc tử ngũ hành ký, Master Mo's Records of theFive Phases), and successfully used its medicines and amulets, "By grasping a pole he becomes a tree. He plants something, and it immediately produces edible melons or fruit. He draws a line on the ground, and it becomes a river; he piles up dirt and it becomes a hill. He sits down and causes the Traveling Canteen to arrive [ tọa trí hành trù ]."[43]

Shenxian zhuan

[edit]The c. 318Shenxian zhuan(Hagiographies of Divine Transcendents) usesxingchu( hành trù, Mobile Kitchen) six times. The hagiography of Wang Yuan gives a detailed description of summoning axingchu.Other adepts who are also said to have this ability include Li Gen, Liu Jing, Zuo Ci, Liu Zheng, and Taixuan nü.[44]

First, the hagiography of Wang Yuan ( vương viễn ) andMagu(Cannabis Maiden) says Wang was a Confucianist scholar who quit his official post during the reign (146–168 CE) ofEmperor Huan of Hanand went into the mountains to study Daoist techniques. Wang achievedxiantranscendence throughshijie"liberation by means of a simulated corpse", described with the traditionalcicada metaphor,his "body disappeared; yet the cap and garments were completely undisturbed, like a cicada shell." During his travels, Wang met the peasant Cai Jing ( thái kinh ), whosephysiognomyindicated he was destined to become a transcendent, so Wang took him on as a disciple, taught him the basic techniques, and left. Soon afterwards Cai also used alchemicalshijieliberation, his body became extremely hot, and his flesh and bones melted away for three days. "Suddenly he had vanished. When his family looked inside the blanket, only his outer skin was left, intact from head to foot, like a cicada shell."[45]

After Cai had been gone for "over a decade", he unexpectedly returned home, looking like a young man, announced to his family that Lord Wang would visit on the "seventh day of the seventh month" (later associated with theCowherd and Weaver Girllovers' festival), and ordered them to "prepare great quantities of food and drink to offer to his attendants." When Wang Yuan and his heavenly entourage arrived on the auspicious "double-seven" day, he invited his old friend Magu to join their celebration because it had been over five hundred years since she had been "in the human realm." When the Cannabis Maiden and her attendants arrived at Cai's household,

She appeared to be a handsome woman of eighteen or nineteen; her hair was done up, and several loose strands hung down to her waist. Her gown had a pattern of colors, but it was not woven; it shimmered, dazzling the eyes, and was indescribable – it was not of this world. She approached and bowed to Wang, who bade her rise. When they were both seated, they called for the travelling canteen [ tọa định triệu tiến hành trù ]. The servings were piled up on gold platters and in jade cups without limit. There were rare delicacies, many of them made from flowers and fruits, and their fragrance permeated the air inside [Cai's home] and out. When the meat was sliced and served, [in flavor] it resembled broiledmoand was announced askirinmeat.[46]

Compare Maspero's translation, "everyone steps forth to 'perform the Kitchen'".[47]Guo Pu's commentary to theClassic of Mountains and Seasdescribed themò( mô,giant panda) as "bear-like, black and white, and metal-eating";[48]and the mysticalqilinbeast is sometimes identified as a Chinese unicorn.[49]

Wang Yuan then announced to the Cai family that he had brought some exceptional wine from the Tianchu ( thiên trù, Heavenly Kitchen) asterism.

I wish to present you all with a gift of fine liquor. This liquor has just been produced by the celestial kitchens. Its flavor is quite strong, so it is unfit for drinking by ordinary people; in fact, in some cases it has been known to burn people's intestines. You should mix it with water, and you should not regard this as inappropriate. "With that, he added adouof water to ashengof liquor, stirred it, and presented it to the members of Cai Jing's family. On drinking little more than ashengof it each, they were all intoxicated. After a little while, the liquor was all gone.[50]

In traditionalChinese units of measurement,adǒu(Đấu) was approximately equivalent to 10 liters and ashēngThăng) approximately 1 liter.

Second, theShenxian zhuannarrative of Li Gen ( lý căn ) says he studied under Wu Dawen ( ngô đại văn ) and obtained a method for producing alchemical gold and silver.

Li Gen could transform himself [into other forms] and could enter water and fire [without harm]. He could sit down and cause the traveling canteen to arrive, and with it could serve twenty guests [ tọa trí hành trù năng cung nhị thập nhân ]. All the dishes were finely prepared, and all of them contained strange and marvelous foods from the four directions, not things that were locally available.[51]

Third, Liu Jing ( lưu kinh ) was an official underEmperor Wen of Han(r. 180–157 BCE) who "abandoned the world and followed Lord Zhang trương quân ofHandanto study the Way. "By using methods for subsisting on" efflorescence of vermilion "pills [ chu anh hoàn ] and" cloud-mother [mica] "pills, Liu" lived to be one hundred thirty years old. To look at him, one would judge him to be a person in his thirties. "He could also foretell the auspiciousness of future events.[52]

The Shangqing (Supreme Purity) traditionHan Wu Di neizhuan( hán võ đế nội truyện, Esoteric Traditions ofHan Emperor Wu), which was written between 370 and 500, has some later accretions that resembleShenxian zhuan.[53]The passage about Liu Jing says,

Later he served Ji Zixun [ kế tử huấn, i.e., Ji Liao kế liêu ] as his teacher. Zixun transmitted to him all the secret essentials of theFive Thearchs,Numinous Flight (lingfei,Linh phi ), the sixjiaspirits, the Twelve Matters (shier shiThập nhị sự ), and the Perfected Forms of the Ten Continents of Divine Transcendents (shenxian shizhou zhenxiang thần tiên thập châu chân hình ). Liu Jing practiced them all according to the instructions, and they were mightily efficacious. He could summon ghosts and spirits, immediately cause wind and rain to arise, cause the traveling canteen to arrive [ danh trí hành trù ], and appear and disappear at will. He also knew the auspiciousness or inauspiciousness of people's future affairs and of particular days.[54]

Fourth, the transcendentZuo Ci( tả từ ) was afangshi( "method master" ) famous for his abilities at divination,fenshenmultilocation, andshapeshifting,[55]

Seeing that the fortunes of the Han house were about to decline, he sighed and said, "As we move into this declining [astral] configuration, those who hold eminent offices are in peril, and those of lofty talent will die. Winning glory in this present age is not something to be coveted." So he studied arts of the Dao. He understood particularly well [how to summon] the sixjiaspirits, how to dispatch ghosts and other spirits, and how to sit down and call for the traveling canteen [ tọa trí hành trù ].[56]

Fifth, theShenxian zhuansays that Liu Zheng ( lưu chính ) used the same alchemical text attributed to Mozi that theBaopuzisays was used by Liu Gen ( lưu căn, or Liu Jun'an lưu quân an.[57]

Later he arranged [a copy of] Master Mo's Treatise on the Five Phases (Mozi wuxing jiMặc tử ngũ hành ký ) and, [based on it], ingested "efflorescence of vermilion" pills. He lived for more than one hundred eighty years, and his complexion was that of a youth. He could transform himself into other shapes and conceal his form; multiply one person into a hundred or a hundred into a thousand or a thousand into ten thousand; conceal a military force of three brigades by forming them into a forest or into birds and beasts, so that they could easily take their opponents' weapons without their knowledge. Further, he was capable of planting fruits of all types and causing them immediately to flower and ripen so as to be ready to eat. He could sit down and cause the traveling canteen to arrive [ sinh trí hành trù ], setting out a complete meal for up to several hundred people. His mere whistling could create a wind to set dust swirling and blow stones about.[58]

Transcendental whistlingwas an ancient Daoist yogic technique.

Sixth, the brief hagiography of the female transcendent Taixuan nü ( thái huyền nữ, Woman of the Grand Mystery) says.

The Woman of the Grand Mystery was surnamed Zhuan chuyên and named He hòa. While still young, she was bereaved of her husband, so she practiced the Way. Disciplining herself in the arts of the Jade Master, (Yuzi) she could sit down and cause the traveling canteen to arrive [ tọa trí hành trù ], and there was no sort of transformation she could not accomplish.[59]

In addition, theShenxian zhuanhagiography for Mao Ying ( mao doanh ) describes what sounds like axingchuwithout using the name.[60]After twenty years studying the Dao, Mao Ying returned home to his parents and announced that he had been commanded to enter heaven and become a transcendent. The people of his home village came to give him a going-away party, and Mao said,

"I am touched by your sincere willingness to send me off, and I deeply appreciate your intention. But please come empty-handed; you need not make any expenditure. I have a means whereby to provide a feast for us all." On the appointed day, the guests all arrived, and a great banquet was held. Awnings of blue brocade were spread out, and layers of white felt were spread out beneath them. Rare delicacies and strange fruits were piled up and arrayed. Female entertainers provided music; the sounds of metal and stone mingled together, and the din shook Heaven and Earth; it could be heard from severalliaway. Of the more than one thousand guests present that day, none failed to leave intoxicated and sated.[61]

Mao Ying and his brothers Mao Gu ( mao cố ) and Mao Zhong ( mao trung ) are considered of the founders of theShangqing Schoolof Daoism.

Shangqing Daoists took the stock literary phrasezuo zhi xingchu( tọa trí hành trù )—used above in theBaopuzifor Liu Gen, "sits down and causes the Traveling Canteen to arrive",[62]and in theShenxian zhuanfor Li Gen, Zuo Ci, and Taixuan nü, "sit down and cause the traveling canteen to arrive"[63]—and actualized it as a visualization technique for "making the movable cuisines come [while] sitting [in meditation]".[30]"This method, accessible only to the initiate who possessed the proper series of talismans (fuPhù ) and had mastered certain visualization techniques, conferred powers to become invisible, to cause thunder, and to call for rain. "This form ofsitting meditationwas so popular during the Tang period thatChinese Esoteric Buddhismalso adopted it.[30]

WuchuFive Kitchens meditation

[edit]Following upon the Celestial Masters liturgical Kitchen feasts andxiantranscendents' Mobile Kitchens, the third stage of Daoistchutraditions was theTang dynasty(618–907)wǔchú( ngũ trù, Five Kitchens) contemplation technique, which recast the concept of ritual banquets in terms of psychophysiologicalneidanInternal Alchemy.[8]In Chinese cosmological wuxing Five Phases correspondence theory, thewuchuFive Kitchens orwuzang( ngũ tạng, Five Viscera / Orbs) system includes not only the physiological internal organs (lungs, kidneys, liver, gallbladder, and spleen), but also the associated psychological range of mental and emotional states.[64]The 735Wuchu jing( ngũ trù kinh, Scripture of the Five Kitchens), which poetically describes a visualization practice for circulatingqienergies through the Five Viscera, was so popular that Tang Buddhists forged the esotericSānchú jīng( tam trù kinh, Sutra of the Three Kitchens) based on the Daoist text.[65]

There are two extant editions ofWuchu jingtranslated by Livia Kohn.[66]First, the 763 TangDaozang(Daoist Canon) edition titledLaozi shuo Wuchu jing zhu( lão tử thuyết ngũ trù kinh, Commentary to the Scripture of the Five Kitchens as Revealed byLaozi) contains a preface dated 735 and a commentary, both signed by Yin Yin ( doãn âm, d. 741). The reduplicatedly named Yin Yin was a prominent Daoist and Confucian scholar underEmperor Xuanzong of Tang(r. 712–756), and abbot of the Suming guan ( túc minh quan, Abbey of Reviving Light) temple in the capitalChang'an.The late TangCelestial MasterZhao Xianfu ( triệu tiên phủ, fl. 732) also wrote a commentary.[8]Second, the 1019Yunji Qiqian(Seven Bamboo Tablets of the Cloudy Satchel) anthology edition titledWuchu jing qifa( ngũ trù kinh khí pháp, Energetic Methods of the Scripture of the Five Kitchens), also includes Yin's commentary, with slight variations, such as noting the text was presented to the emperor in 736.[8]Theqi"energetic" methods of the text are recommended bySima Chengzhen( tư mã thừa trinh, 647–735) in hisFuqi jingyi lun( phục khí tinh nghĩa luận, Essay on the Essential Meaning of Breath Ingestion) text on physical self-cultivation.[65]Although the presence of Yin's preface might suggest a Tang date for theWuchu jing,the origins of this text may be much earlier.Ge Hong's c. 318Baopuzimentions aXingchu jing( hành trù kinh, Scripture of the Movable Kitchens) and aRiyue chushi jing( nhật nguyệt trù thực kinh, Scripture of the Kitchen Meals for the Sun and the Moon), which could be the ancestors of the received texts.[65]

The c. 905Daojiao lingyan ji( đạo giáo linh nghiệm ký, Record of Daoist Miracles), written by the Daoist priest, author, and court officialDu Guangting,says aBuddhist monkfraudulently transformed theWuchu jingScripture of the Five Kitchens into theSanchu jing( tam trù kinh, Sutra of the Three Kitchens). Du records that theChinese Buddhist canonof the Tang period contained a text titledFo shuo san tingchu jing( phật thuyết tam đình trù kinh, Sutra of the Three Interrupted Kitchens, Preached by the Buddha).[67]According to Du Guangting, the monk Xingduan ( hành đoan ), who had "a presumptuous and fraudulent disposition", saw that the widely circulated DaoistWuchu jingconsisted of five stanzas (jìKệ, "gatha;poetic verse; versified utterance ") of incantations (zhòuChú, "mantra;religious incantation; mystical invocation "), rearranged them, and expanded the title intoFo shuo san tingchu jing( phật thuyết tam đình trù kinh ). "The five incantations he turned into 'five sutras spoken byTathagata,' and at the end he added a hymn. The additional phrases amounted to no less than a page. "Verellen suggests that the scripture, with its" Buddho-Daoist content and quasi-magical use ", originated as a lateSix Dynasties(220–589) Tantriczhoujing( chú kinh, "incantations scripture", cf. theDivine Incantations Scripture).[68]

Du Guangting gives a lengthy narrative about the Daoist miracle involving supernatural retribution for Xingduan's forgery. One day after the monk had already given several copies of the altered scripture to others, a "divine being eight or nine feet tall" and holding a sword reprimands him for the counterfeiting and brandishes his sword to strike the monk. As Xingduan "wards off the blow with his hand, several fingers are lopped off", he begs for mercy, and the Daoist deity agrees to spare his life if he retrieves and destroys all the fakes. Xingduan and his companions search everywhere for the texts, but can only find half of them, the remainder having already been carried abroad by Buddhist monks. Xingduan prepares ten fresh copies of the original scripture, offers incense, repents, and burns the altered copies. Then the divine being reappears and announces: "Having vilified the sage's text, restitution won't save you—you do not deserve to escape death", the monk falls prostrate and dies on the spot.[69]

In the present day, early copies of this apocryphal Buddhist sutra have been preserved. Four textual versions were discovered in the ChineseDunhuang manuscripts,two versions, dated 1099 and 1270, are kept in the JapaneseMount Kōyamanuscripts. In addition, the modern JapaneseTaishō Tripiṭakacanon includes the text.[70]

The highly abstractWuchu jingmystical poem comprises five stanzas consisting of four five-character lines each. TheYunqi qiqianedition shows that the five stanzas were associated with the Five Directions of space: east (lines 1–4), south (lines 5–8), north (lines 9–12), west (lines 13–16), and center (lines 17–20).[8]For example, the first four lines:[71]

Nhất khí hòa thái hòa |

Theqiof universal oneness merges with the harmony of cosmic peace. |

The content of theWuchu jingguides adepts toward a detached mental state of non-thinking and equanimity. The Five Kitchens refer toneidanInternal Alchemy "qi-processing on a subtle-body level ", and signify the energetic, transformative power of the Five Viscera.[72]Yin Yin's introduction says,

As long as you dwell in theqiof universal oneness [ nhất khí ] and in the harmony of cosmic peace [ thái hòa ], the five organs [ ngũ tạng ] are abundant and full and the five spirits [ ngũ thần ] are still and upright. "When the five organs are abundant, all sensory experiences are satisfied; when the five spirits are still, all cravings and desires are eliminated. This scripture expounds on how the five organs taking inqiis like someone looking for food in a kitchen. Thus, its title: "Scripture of the Five Kitchens."[73]

Commenting on Yin's interpretation, Du Guangting claims more explicitly that practicing this scripture will enable an adept to stop eating.[8]

Techniques in theWuchu jing(Ngũ trù kinh,Scripture of the Five Kitchens) mainly involve visualizing the Five Viscera of the body and chanting incantations. These methods supposedly allow the adept to obtain satisfaction and harmony, and, after some years of training, even transcendence.[74]Despite this concern with the human body, the text strongly emphasizes mental restructuring over physical practices, saying that "accumulating cultivation will not get you to detachment" and that methods of ingestion are ultimately useless. However, reciting the scripture is beneficial, especially if combined with mental and ethical practices, so that "you will easily get the true essentials of cultivating the body-self and protecting life." More specifically, chanting the text one hundred times and practicing the harmonization of the fiveqiallows adepts to abstain from grain and eliminate hunger.[75]Many present-day Daoists consider theWuchu jingas a talismanic text to be chanted for protection.[72]

References

[edit]- ^Bishop 2016.

- ^abcMaspero 1981,p. 290.

- ^abcdMollier 2008a,p. 279.

- ^abDespeux 2008.

- ^Digital Dictionary of Buddhism.[full citation needed]

- ^Stein 1979.

- ^abMaspero 1981.

- ^abcdefVerellen 2004.

- ^abCampany 2005.

- ^abKleeman 2008.

- ^abMollier 2008a.

- ^abMollier 2009.

- ^Kroll 2017,p.[page needed].

- ^Maspero 1971.

- ^Mollier 1999.

- ^Ware 1966.

- ^Sivin 1968.

- ^Penny 2000.

- ^Campany 2002.

- ^Needham, Ho Ping-Yü & Lu Gwei-Djen 1976,p. 29.

- ^Sivin 1968,p.[page needed].

- ^Stein 1979,p. 57.

- ^Stein 1979,p. 75.

- ^Stein 1979,p. 71.

- ^Stein 1979,p. 74.

- ^Maspero 1981,pp. 34–35.

- ^Stein 1979,p. 56.

- ^Ware 1966,p. 158.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 29.

- ^abcMollier 2008a,p. 280.

- ^Campany 2005,pp. 46–47.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 221.

- ^Ware 1966,pp. 384, 380, 381.

- ^Ware 1966,p. 84; cf.Campany 2002,p. 290.

- ^Ware 1966,p. 188.

- ^Ware 1966,p. 190.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 75.

- ^Needham, Ho Ping-Yü & Lu Gwei-Djen 1976,p. 86.

- ^Ware 1966,pp. 82–83, noting "fragrant foods served in plates of gold and cups of jade".

- ^Ware 1966,p. 177.

- ^Ware 1966,p. 276.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 248.

- ^Ware 1966,p. 316.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 222.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 260.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 262.

- ^Maspero 1981,p. 291.

- ^Harper 2013,p. 216.

- ^Penny 2008.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 263.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 219.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 249.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 76.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 449.

- ^Pregadio 2008.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 279.

- ^Campany 2002,pp. 240–249.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 322.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 367.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 328.

- ^Campany 2002,p. 327.

- ^Ware 1966,p.[page needed].

- ^Campany 2002,p. 322–323.

- ^Roth 1999,pp. 41–42.

- ^abcMollier 2008b,p. 1051.

- ^Kohn 2010,pp. 198–206.

- ^Verellen 1992,pp. 248–249.

- ^Verellen 1992,pp. 250–251.

- ^Verellen 1992,p. 251.

- ^Mollier 2009,pp. 26–28.

- ^Kohn 2010,pp. 200–201.

- ^abKohn 2010,p. 71.

- ^Kohn 2010,p. 200.

- ^Mollier 2008a,pp. 279–280.

- ^Mollier 1999,pp. 62–63.

- Bishop, Tom (2016).Wenlin Software for learning Chinese.version 4.3.2.

- Campany, Robert Ford (2001). "Ingesting the Marvelous: The Practitioner's Relationship to Nature According to Ge Hong". In N.J. Girardot; James Miller; Xiaogan Liu (eds.).Daoism and Ecology: Ways within a Cosmic Landscape.Harvard University Press. pp. 125–146.

- Campany, Robert Ford (2002).To Live as Long as Heaven and Earth: A Translation and Study of Ge Hong's Traditions of Divine Transcendents.University of California Press.

- Campany, Robert Ford (2005). "The Meanings of Cuisines of Transcendence in Late Classical and Early Medieval China".T'oung Pao.91(1): 1–57.doi:10.1163/1568532054905124.

- Despeux, Catherine (2008). "BiguTích cốc abstention from cereals ". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.pp. 233–234.

- Harper, Donald (2013). "The Cultural History of the Giant Panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) in Early China ".Early China.Vol. 35/36. pp. 185–224.

- Kleeman, Terry (2008). "SanhuiTam hội Three Assemblies ". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.pp. 839–840.

- Kohn, Livia (2010).Sitting in Oblivion: The Heart of Daoist Meditation.Three Pines Press.

- Kroll, Paul K. (2017).A Student's Dictionary of Classical and Medieval Chinese(Revised ed.). Brill.

- Maspero, Henri (1971).Le Taoisme et les Religions Chinoises.Paris: Gallimard.

- Maspero, Henri (1981).Taoism and Chinese Religion.University of Massachusetts Press.Translation by Frank A. Kierman Jr. ofMaspero (1971).

- Mollier, Christine (1999). "Les cuisines de Laozi et du Buddha".Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie.11:45–90.doi:10.3406/asie.1999.1150.

- Mollier, Christine (2008a). "ChuTrù 'cuisines'".In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.Routledge. pp. 539–544.

- Mollier, Christine (2008b). "Wuchu jingNgũ trù kinh Scripture of the Five Cuisines ". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.Routledge. p. 1051.

- Mollier, Christine (2009).Buddhism and Taoism Face to Face: Scripture, Ritual, and Iconographic Exchange in Medieval China.University of Hawaii Press.

- Needham, Joseph; Ho Ping-Yü; Lu Gwei-Djen (1976).Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. V: Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Part 3: Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Historical Survey, from Cinnabar Elixirs to Synthetic Insulin.Cambridge University Press.

- Penny, Benjamin (2000). "Immortality and Transcendence". In Livia Kohn (ed.).Daoism Handbook.Brill. pp. 109–133.

- Penny, Benjamin (2008). "Magu ma cô". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.Routledge. pp. 731–732.

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2008). "Zuo Ci tả từ". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.).The Encyclopedia of Taoism.Routledge. pp. 1304–1305.

- Roth, Harold D. (1999).Original Tao: Inward Training (Nei-yeh) and the Foundations of Taoist Mysticism.Columbia University Press.

- Sailey, Jay (1978).The Master Who Embraces Simplicity: A study of the philosopher Ko Hung, A.D. 283–343.Chinese Materials Center.

- Sivin, Nathan (1968).Chinese Alchemy: Preliminary Studies.Harvard University Press.

- Stein, Rolf A. (1971). "Les fetes de cuisine du Taoisme religieux".Annuaire du College de France.71:431–440.

- Stein, Rolf A. (1972). "Speculations mystiques et themes relatifs aux 'cuisines' du Taoisme".Annuaire du College de France.72:489–499.

- Stein, Rolf A. (1979). "Religious Taoism and Popular Religion from the Second to Seventh Centuries". In Holmes Welch; Anna K. Seidel (eds.).Facets of Taoism: Essays in Chinese Religion.Yale University Press. pp. 53–81.

- Verellen, Franciscus (1992). "'Evidential Miracles in Support of Taoism': The Inversion of a Buddhist Apologetic Tradition in Late Tang China ".T'oung Pao.78:2I7–263.doi:10.1163/156853292X00018.

- Verellen, Franciscus (2004). "Laozi shuo wuchu jing zhuLão tử thuyết ngũ trù kinh chú ". In Kristofer Schipper; Franciscus Verellen (eds.).The Taoist Canon: A Historical Companion to the Daozang.3 vols. University of Chicago Press. pp. 351–352.

- Ware, James R. (1966).Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The 'Nei Pien' of Ko Hung.Dover.