Circular reasoning

| Part ofa serieson |

| Pyrrhonism |

|---|

|

|

|

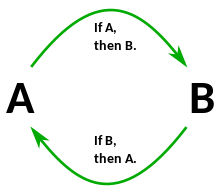

Circular reasoning(Latin:circulus in probando,"circle in proving";[1]also known ascircular logic) is alogical fallacyin which the reasoner begins with what they are trying to end with.[2]Circular reasoning is not a formal logical fallacy, but a pragmatic defect in an argument whereby the premises are just as much in need of proof or evidence as the conclusion, and as a consequence the argument fails to persuade. Other ways to express this are that there is no reason to accept the premises unless one already believes the conclusion, or that the premises provide no independent ground or evidence for the conclusion.[3]Circular reasoning is closely related tobegging the question,and in modern usage the two generally refer to the same thing.[4]

Circular reasoning is often of the form: "A is true because B is true; B is true because A is true." Circularity can be difficult to detect if it involves a longer chain of propositions.

An example of circular reasoning is: "Alkaline wateris healthy because it results in health benefits, and it has health benefits because it is healthy ".

History[edit]

The problem of circular reasoning has been noted inWestern philosophyat least as far back as thePyrrhonistphilosopherAgrippawho includes the problem of circular reasoning among hisFive Tropes of Agrippa.The Pyrrhonist philosopherSextus Empiricusdescribed the problem of circular reasoning as "the reciprocaltrope":

The reciprocal trope occurs when what ought to be confirmatory of the object under investigation needs to be made convincing by the object under investigation; then, being unable to take either in order to establish the other, wesuspend judgementabout both.[5]

The problem of induction[edit]

Joel FeinbergandRuss Shafer-Landaunote that "using the scientific method to judge the scientific method is circular reasoning". Scientists attempt to discover the laws of nature and to predict what will happen in the future, based on those laws. The laws of nature are arrived at throughinductive reasoning.David Hume'sproblem of inductiondemonstrates that one must appeal to theprinciple of the uniformity of natureif they seek to justify their implicit assumption that laws which held true in the past will also hold true in the future. Since the principle of the uniformity of nature is itself an inductive principle, any justification for induction must be circular. But asBertrand Russellobserved, "The method of 'postulating' what we want has many advantages; they are the same as the advantages of theft over honest toil".[6]

See also[edit]

- Affirming the consequent

- Argument from authority

- Catch-22 (logic)

- Circular definition

- Circular reference

- Circular reporting

- Coherentism

- Formal fallacy

- I'm entitled to my opinion

- Ipse dixit,a fallacy that can be translated as "because I said so"

- List of cognitive biases

- Paradox

- Polysyllogism

- Problems with economic models

- Self-reference

- Tautology (logic)

References[edit]

- ^Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 389.

- ^Dowden, Bradley (27 March 2003)."Fallacies".Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.Archivedfrom the original on 9 October 2014.RetrievedApril 5,2012.

- ^Nolt, John Eric; Rohatyn, Dennis; Varzi, Achille (1998).Schaum's outline of theory and problems of logic.McGraw-Hill Professional. p.205.ISBN9780070466494.

- ^Walton, Douglas (2008).Informal Logic: A Pragmatic Approach.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521886178.

- ^Sextus Empiricus,Pyrrhōneioi hypotypōseisi., from Annas, J.,Outlines of ScepticismCambridge University Press.(2000).

- ^Feinberg, Joel; Shafer-Landau, Russ (2008).Reason and responsibility: readings in some basic problems of philosophy.Cengage Learning. pp. 257–58.ISBN9780495094920.