Acre, Israel

Acre

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| •ISO 259 | ʕAkko |

| Coordinates:32°55′40″N35°04′54″E/ 32.92778°N 35.08167°E | |

| Grid position | 156/258PAL |

| Country | Israel |

| District | Northern |

| Founded | 3000BC(Bronze Age settlement) 1550BC(Canaanite settlement) 1104(Crusader rule) 1291(Mamluk rule) 1948(Israeli city) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Amihai Ben Shlush (since 2024)[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 13,533dunams(13.533 km2or 5.225 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[2] | |

| • Total | 51,420 |

| • Density | 3,800/km2(9,800/sq mi) |

| Official name | Old City of Acre |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, v |

| Reference | 1042 |

| Inscription | 2001 (25thSession) |

| Area | 63.3 ha |

| Buffer zone | 22.99 ha |

Acre(/ˈɑːkər,ˈeɪkər/AH-kər,AY-kər), known locally asAkko(Hebrew:עַכּוֹ,ʻAkkō) andAkka(Arabic:عكّا,ʻAkkā), is acityin the coastal plain region of theNorthern DistrictofIsrael.

The city occupies a strategic location, sitting in a natural harbour at the extremity ofHaifa Bayon the coast of theMediterranean'sLevantine Sea.[3]Aside from coastal trading, it was an important waypoint on the region'scoastal roadand the road cutting inland along theJezreel Valley.The first settlement during theEarly Bronze Agewas abandoned after a few centuries but a large town was established during theMiddle Bronze Age.[4]Continuously inhabited since then, it is amongthe oldest continuously inhabited settlements on Earth.[5]It has, however, been subject to conquest and destruction several times and survived as little more than a large village for centuries at a time.

Acre was a hugely important city during theCrusadesas a maritime foothold on the Mediterranean coast of thesouthern Levantand was the site of several battles, including the1189–1191 Siege of Acreand1291 Siege of Acre.It was the last stronghold of the Crusaders in theHoly Landprior to that final battle in 1291. At the end of Crusader rule, the city was destroyed by theMamluks,thereafter existing as a modest fishing village until the rule ofZahir al-Umarin the 18th century.[6]

In 1947, Acre formed part ofMandatory Palestineand had a population of 13,560, of whom 10,930 were Muslim and 2,490 were Christian. As a result of theUnited Nations Partition Plan for Palestineand subsequent1948 Arab-Israeli war,the population of the town dramatically changed as its Palestinian-Arab population was expelled or forced to flee; it was then resettled by Jewish immigrants.[7]In present-day Israel, the population was 51,420 in 2022,[2]made up ofJews,Muslims,Christians,Druze,andBaháʼís.[8]In particular, Acre is the holiest city of theBaháʼí Faithin Israel and receives manypilgrimsof that faith every year. Acre is one of Israel'smixed cities;32% of the city's population isArab.The mayor is Shimon Lankri, who was re-elected in 2018 with 85% of the vote.

Names

The etymology of the name is unknown.[9]Afolk etymologyinHebrewis that, when the ocean was created, it expanded until it reached Acre and then stopped, giving the city its name (in Hebrew,ad kohmeans "up to here" and no further).[9]

Acre seems to be recorded inEgyptian hieroglyphs,probably being theʿKYin theexecration textsfrom around 1800BC[10]and the "Aak" in the tribute lists ofThutmose III(1479–1425BC).[citation needed]

TheAkkadiancuneiformAmarna lettersalso mention an "Akka" in the mid-14th centuryBC.[11][12]On its native currency, Acre's name was writtenʿK(Phoenician:𐤏𐤊).[13]It appears in Assyrian[9]and once inBiblical Hebrew.[14]

Acre was known to theGreeksasÁkē(Greek:Ἄκη), a homonym for a Greek word meaning "cure".Greek legendthen offered a folk etymology thatHerculeshad foundcurative herbsat the site after one of his many fights.[15]This name wasLatinizedasAce.Josephus's histories also transcribed the city into Greek asAkre.

The city appears in theBabylonian Talmudwith theJewish Babylonian AramaicnameתלבושTalbushof uncertain etymology.[16]

Under theDiadochi,thePtolemaic Kingdomrenamed the cityPtolemaïs(Koinē Greek:Πτολεμαΐς,Ptolemaΐs) and theSeleucid EmpireAntioch(Ἀντιόχεια,Antiókheia).[13]As both names were shared by a great many other towns, they were variously distinguished. The Syrians called it"Antioch in Ptolemais"(Ἀντιόχεια τῆς ἐν Πτολεμαΐδι,Antiókheia tês en Ptolemaΐdi).[13]

Under Claudius, it was also briefly known asGermanicia in Ptolemais(Γερμανίκεια τῆς ἐν Πτολεμαΐδι,Germaníkeia tês en Ptolemaΐdi).[13]As aRoman colony,it was notionally refounded and renamedColonia Claudii Caesaris Ptolemais[17]orColonia Claudia Felix Ptolemais Garmanica Stabilis[18]after its imperial sponsorClaudius;it was known asColonia Ptolemaisfor short.[17]

During the Crusades, it was officially known asSainct-Jehan-d'Acreor more simplyAcre(ModernFrench:Saint-Jean-d'Acre[sɛ̃ʒɑ̃dakʁ]), after theKnights Hospitallerwho had their headquarters there and whosepatron saintwasSaint John the Baptist.This name remained quite popular in the Christian world until modern times, often translated into the language being used:Saint John of Acre(in English),San Juan de Acre(inSpanish),Sant Joan d'Acre(inCatalan),San Giovanni d'Acri(inItalian), etc.

History

Early Bronze Age

Acre lies at the northern end ofa wide baywithMount Carmelat the south.[10]It is the best naturalroadsteadon the southernPhoeniciancoast and has easy access to theValley of Jezreel.[10]It was settled early and has always been important for the fleets of kingdoms and empires contesting the area,[10]serving as the main port for the entire southern Levant up to the modern era.[19]

The ancient town was located atopTelʿAkkō (Hebrew) or Tell al-Fuḫḫār (Arabic), 1.5 km (0.93 mi) east of the present city[3]and 800 m (2,600 ft) north of theNa'aman River.In antiquity, however, it formed an easily protected peninsula[19]directly beside the former mouth of the Na'aman or Belus.[10]The earliest discovered settlement dates to around 3000BC[3]during the Early Bronze Age, but appears to have been abandoned after a few centuries, possibly because of inundation of its surrounding farmland by theMediterranean.[4]

Middle Bronze Age

Acre was resettled as an urban centre during the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000–1550BC) and has been continuously inhabited since then.[4]Egyptianexecration textsrecord one 18th-century ruler as Tūra-ʿAmmu (Tꜣʿmw).[10]

Late Bronze Age

Acre was listed among the conquests of the EgyptianpharaohThutmose III.[10]

Amarna period

In theAmarna Period(c. 1350BC), there was turmoil in Egypt's Levantine provinces. The Amarna Archive contains letters concerning the ruler(s) of Acco. In one, King Biridiya ofMegiddocomplains toAmenhotep IIIorAkhenatenof the king of Acre, whom he accuses of treason for releasing the capturedHapirukingLabayaofShecheminstead of delivering him to Egypt.[20]Excavations of Tel ʿAkkō have shown that this period of Acre involved industrial production of pottery, metal, and other trade goods.[19]

In Amarna LetterEA 232,Surata (msu₂-ra-ta) is the Man of Akka (LU₂uruak-ka). The letter is sent to the King of Egypt, and it contains Canaanite glosses. Surata is also mentioned in letters from Byblos (EA 085), Gath (EA 366), and Megiddo (EA 245).

Iron Age

During the supposedConquest of Israelby theHebrewleaderJoshua),Acre was allotted to thetribeofAsher,[21]who however failed to take it.[22]Acre continued as aPhoeniciancity[23]and was referenced as aPhoeniciancity by theAssyrians.[10]Josephus,however, claimed it as a province of theKingdom of IsraelunderSolomon.

Around 725BC, Acre joinedSidonandTyrein a revolt against theNeo-Assyrian emperorShalmaneser V.[23]There is a cleardestruction layerin the ruins, probably dating to the 7th century BC.[24]

Persian period and classical-Greek antiquity

Acre served as a major port of thePersian Empire,[10]withStrabonoting its importance in campaigns against the Egyptians. According to Strabo andDiodurus Siculus,Cambyses IIattacked Egypt after massing a huge army on the plains near the city of Acre. The Persians expanded the town westward and probably improved its harbor[24]and defenses. In December 2018, archaeologists digging at the site ofTell Keisanin Acre unearthed the remains of a Persian military outpost that might have played a role in the successful 525 BCAchaemenidinvasion of Egypt.[25][26]The city's industrial production continued into the late Persian era, with particularly expanded iron works.[19]

The Persian-period fortifications at Tell Keisan were later heavily damaged during Alexander's fourth-century BC campaign to drive the Achaemenids out of the Levant.[25][26]

AfterAlexander's death,his main generalsdivided his empireamong themselves. At first, theEgyptian Ptolemiesheld the land around Acre.PtolemyIIrenamed the city Ptolemais in his own and his father's honour in the 260sBC.[13]

Antiochus IIIconquered the town for theSyrian Seleucidsin 200BC. In the late 170s or early 160sBC,AntiochusIVfounded a Greek colony in the town, which he named Antioch after himself.[13]

About 165BCJudas Maccabeusdefeated the Seleucids in several battles inGalilee,and drove them into Ptolemais. About 153BCAlexander Balas,son of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, contesting the Seleucid crown withDemetrius,seized the city, which opened its gates to him. Demetrius offered many bribes to theMaccabeesto obtain Jewish support against his rival, including the revenues of Ptolemais for the benefit of theTemple in Jerusalem,but in vain.Jonathan Apphusthrew in his lot with Alexander; Alexander and Demetrius met in battle and the latter was killed. In 150BC Alexander received Jonathan with great honour in Ptolemais. Some years later, however, Tryphon, an officer of theSeleucid Empire,who had grown suspicious of the Maccabees, enticed Jonathan into Ptolemais and there treacherously took him prisoner.

The city was captured byAlexander Jannaeus(ruledc. 103–76BC),Tigranes the Great(r. 95–55BC), andCleopatra(r. 51–30BC). HereHerod the Great(r. 37–4BC) built agymnasium.

Roman colony

Around 37 BC, the Romans conquered the Hellenized Phoenician port-city called Akko. It became a colony in southernRoman Phoenicia,calledColonia Claudia Felix Ptolemais Garmanica Stabilis.[18]Ptolemais stayed Roman for nearly seven centuries until 636 AD, when it was conquered by the Muslim Arabs. UnderAugustus,agymnasiumwas built in the city. In 4 BC, the Roman proconsulPublius Quinctilius Varusassembled his army there in order to suppress the revolts that broke out in the region following the death ofHerod the Great.

The Romans built a breakwater and expanded the harbor at the present location of the harbor....In the Roman/Byzantine period, Acre-Ptolemais was an important port city. It minted its own coins, and its harbor was one of the main gates to the land. Through this port the Roman Legions came by ship to crush the Jewish revolt in 67AD. It also served was used as connections to the other ports (for example, Caesarea and Jaffa)....The port of Acre (Ptolemais) was a station on Paul's naval travel, as described in Acts of the Gospels (21, 6-7): "And when we had taken our leave one of another, we took ship; and they returned home again. And when we had finished our course from Tyre, we came to Ptolemais, and saluted the brethren, and abode with them one day".[27]

During the rule of the emperorClaudiusthere was a building drive in Ptolemais and veterans of the legions settled here. The city was one of four colonies (withBerytus,Aelia CapitolinaandCaesarea Maritima) created in the ancient Levant by Roman emperors for Roman veterans.[28]

During theGreat Jewish Revolt(66–73 CE), Acre functioned as a staging point for bothCestius's andVespasian's campaigns to suppress the revolt inJudaea.[29]

The city was a center ofRomanizationin the region, but most of the population was made of local Phoenicians and Jews: as a consequence after theHadriantimes the descendants of the initial Roman colonists no longer spokeLatinand had become fully assimilated in less than two centuries (however the local society's customs were Roman).

The ChristianActs of the ApostlesdescribesLuke the Evangelist,Paul the Apostleand their companions spending a day in Ptolemais with their Christian brethren.[30]

An important Roman colony (colonia) was established at the city that greatly increased the control of the region by the Romans over the next century with Roman colonists translated there fromItaly.The Romans enlarged the port and the city grew to more than 20,000 inhabitants in the second century under emperorHadrian.Ptolemais greatly flourished for two more centuries.[31]

Byzantine period

After the permanent division of theRoman Empirein 395 AD, Ptolemais was administered by the successor state, theByzantine Empire.The city started to lose importance and in the seventh century was reduced to a small settlement of less than one thousand inhabitants.[citation needed]

Early Islamic period

Following the defeat of theByzantine armyofHeracliusby theRashidun armyofKhalid ibn al-Walidin theBattle of Yarmouk,and the capitulation of the Christian city of Jerusalem to the CaliphUmar,Acre came under the rule of theRashidun Caliphatebeginning in 638.[5]According to the early Muslim chronicleral-Baladhuri,the actual conquest of Acre was led byShurahbil ibn Hasana,and it likely surrendered without resistance.[32]TheArabconquestbrought a revival to the town of Acre, and it served as the main port of Palestine through theUmayyadandAbbasid Caliphatesthat followed, and through Crusader rule into the 13th century.[5]

The firstUmayyadcaliph,Muawiyah I(r. 661–680), regarded the coastal towns of theLevantas strategically important. Thus, he strengthened Acre's fortifications and settledPersiansfrom other parts of Muslim Syria to inhabit the city. From Acre, which became one of the region's most important dockyards along withTyre,Mu'awiyah launched an attack against Byzantine-heldCyprus.The Byzantines assaulted the coastal cities in 669, prompting Mu'awiyah to assemble and send shipbuilders and carpenters to Acre. The city would continue to serve as the principal naval base ofJund al-Urdunn( "Military District of Jordan" ) until the reign of CaliphHisham ibn Abd al-Malik(723–743), who moved the bulk of the shipyards north to Tyre.[32]Nonetheless, Acre remained militarily significant through the early Abbasid period, with Caliphal-Mutawakkilissuing an order to make Acre into a major naval base in 861, equipping the city with battleships and combat troops.[33]

During the 10th century, Acre was still part of Jund al-Urdunn.[34]Local Arab geographeral-Muqaddasivisited Acre during the earlyFatimid Caliphatein 985, describing it as a fortified coastal city with a largemosquepossessing a substantialolivegrove. Fortifications had been previously built by the autonomous EmirIbn Tulunof Egypt, who annexed the city in the 870s, and provided relative safety for merchant ships arriving at the city's port. When Persian travellerNasir Khusrawvisited Acre in 1047, he noted that the largeJama Masjidwas built ofmarble,located in the centre of the city and just south of it lay the "tomb of the ProphetSalih."[33][35]Khusraw provided a description of the city's size, which roughly translated as having a length of 1.24 kilometres (0.77 miles) and a width of 300 metres (984 feet). This figure indicates that Acre at that time was larger than its current Old City area, most of which was built between the 18th and 19th centuries.[33]

Crusader and Ayyubid period

First Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem (1104–1187)

After four years, thesiege of Acrewas successfully completed in 1104, with the city capitulating to the forces of KingBaldwin I of Jerusalemfollowing theFirst Crusade.The Crusaders made the town their chief port in theKingdom of Jerusalem.On the first Crusade, Fulcher relates his travels with the Crusading armies of King Baldwin, including initially staying over in Acre before the army's advance to Jerusalem. This demonstrates that even from the beginning, Acre was an important link between the Crusaders and their advance into the Levant.[36]Its function was to provide Crusaders with a foothold in the region and access to vibrant trade that made them prosperous, especially giving them access to the Asiatic spice trade.[37]By the 1130s it had a population of around 25,000 and was only matched for size in the Crusader kingdom by the city of Jerusalem. Around 1170 it became the main port of the eastern Mediterranean, and the kingdom of Jerusalem was regarded in the west as enormously wealthy above all because of Acre. According to an English contemporary, it provided more for the Crusader crown than the total revenues of the king of England.[37]

TheAndalusiangeographerIbn Jubayrwrote that in 1185 there was still aMuslimcommunity in the city who worshipped in a small mosque.

Ayyubid intermezzo (1187–1191)

Acre, along withBeirutandSidon,capitulated without a fight to theAyyubidsultanSaladinin 1187, after hisdecisive victoryatHattinand the subsequent Muslim capture of Jerusalem.

Second Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem (1191–1291)

Acre remained in Muslim hands until it was unexpectedlybesiegedby KingGuy of Lusignan—reinforced byPisannaval and ground forces—in August 1189. The siege was unique in the history of the Crusades since the Frankish besiegers were themselves besieged, by Saladin's troops. It was not captured until July 1191 when the forces of theThird Crusade,led byKing Richard I of EnglandandKing Philip II of France,came to King Guy's aid. Acre then served as thede factocapital of the remnant Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1192. During the siege, German merchants fromLübeckandBremenhad founded a field hospital, which became the nucleus of the chivalricTeutonic Order.Upon theSixth Crusade,the city was placed under the administration of the Knights Hospitaller military order. Acre continued to prosper as major commercial hub of the eastern Mediterranean, but also underwent turbulent times due to the bitter infighting among the Crusader factions that occasionally resulted in civil wars.[38]

The old part of the city, where the port and fortified city were located, protrudes from the coastline, exposing both sides of the narrow piece of land to the sea. This could maximize its efficiency as a port, and the narrow entrance to this protrusion served as a natural and easy defense to the city. Both the archaeological record and Crusader texts emphasize Acre's strategic importance—a city in which it was crucial to pass through, control, and, as evidenced by the massive walls, protect.

Acre was the final major stronghold of the Crusader states when much of the Levantine coastline was conquered byMamlukforces. Acre itself fell to SultanAl-Ashraf Khalilin1291.

Mamluk period (1291–1517)

Acre, having been isolated and largely abandoned by Europe, was conquered by Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Khalil ina bloody siege in 1291.In line with Mamluk policy regarding the coastal cities (to prevent their future utilization by Crusader forces), Acre was entirely destroyed, with the exception of a few religious edifices considered sacred by the Muslims, namely the Nabi Salih tomb and the Ayn Bakar spring. The destruction of the city led to popular Arabic sayings in the region enshrining its past glory.[38]

In 1321 the Syrian geographerAbu'l-Fidawrote that Acre was "a beautiful city" but still in ruins following its capture by the Mamluks. Nonetheless, the "spacious" port was still in use and the city was full of artisans.[39]Throughout the Mamluk era (1260–1517), Acre was succeeded bySafedas the principal city of its province.[38]

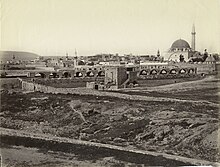

Ottoman period

Incorporated into theOttoman Empirein 1517, it appeared in thecensusof 1596, located in theNahiyaof Acca of theLiwaofSafad.The population was 81 households and 15 bachelors, all Muslim. They paid a fixed tax-rate of 25% on agricultural products, including wheat, barley, cotton, goats, and beehives, water buffaloes, in addition to occasional revenues and market toll, a total of 20,500Akçe.Half of the revenue went to aWaqf.[40][41]English academicHenry Maundrellin 1697 found it a ruin,[42]save for akhan(caravanserai) built and occupied by French merchants for their use,[43]amosqueand a few poor cottages.[42]Thekhanwas named Khan al-Ilfranj after its French founders.[43]

During Ottoman rule, Acre continued to play an important role in the region via smaller autonomous sheikhdoms.[3]Towards the end of the 18th century Acre revived under the rule ofZahir al-Umar,the Arab ruler of the Galilee, who made the city capital of his autonomoussheikhdom.Zahir rebuilt Acre's fortifications, using materials from the city's medieval ruins. He died outside its walls during an offensive against him by the Ottoman state in 1775.[38]

Umar's successor,Jazzar Pasha,further fortified its walls when he virtually moved the capital of theSaida Eyelet( "Province ofSidon") to Acre where he resided.[44]Jazzar's improvements were accomplished through heavy imposts secured for himself all the benefits derived from his improvements. About 1780, Jazzar peremptorily banished the French trading colony, in spite of protests from the French government, and refused to receive a consul.[citation needed]Both Zahir and Jazzar undertook ambitious architectural projects in the city, building several caravanserais, mosques, public baths and other structures. Some of the notable works included theAl-Jazzar Mosque,which was built out of stones from the ancient ruins ofCaesareaandAtlitand theKhan al-Umdan,both built on Jazzar's orders.[43]Under Jazzar, Acre thrived, becoming the third largest city inOttoman Syria.Its population, then largely composed of migrants drawn by its burgeoning development, is estimated at around twenty thousand.[45]

In 1799Napoleon,in pursuance of his scheme for raising a Syrian rebellion against Turkish domination, appeared before Acre, but after a siege of two months (March–May) was repulsed by the Turks, aided by SirSidney Smithand a force of British sailors. Having lost his siege cannons to Smith, Napoleon attempted to lay siege to the walled city defended by Ottoman troops on 20 March 1799, using only his infantry and small-calibre cannons, a strategy which failed, leading to his retreat two months later on 21 May.

Jazzar was succeeded on his death by hismamluk,Sulayman Pasha al-Adil,under whose milder rule the town advanced in prosperity till his death in 1819. After his death,Haim Farhi,who was his adviser, paid a huge sum in bribes to assure thatAbdullah Pasha(son of Ali Pasha, the deputy of Sulayman Pasha), whom he had known from youth, will be appointed as ruler—which didn't stop the new ruler from assassinating Farhi. Abdullah Pasha ruled Acre until 1831, whenIbrahim Pashabesieged and reduced the town and destroyed its buildings. During theOriental Crisis of 1840it was bombarded on 4 November 1840 by the allied British, Austrian and French squadrons, and in the following year restored to Turkish rule.[citation needed]It regained some of its former prosperity after linking with theHejaz Railwayby a branch line fromHaifain 1913.[46]It was the capital of the Acre Sanjak in theBeirut Vilayetuntil the British captured the city on 23 September 1918 duringWorld War I.[46]

Mandatory Palestine

At the beginning of the Mandate period, in the1922 census of Palestine,Acre had 6,420 residents: 4,883 of whom were Muslim; 1,344 Christian; 102 Baháʼí; 78 Jewish and 13Druze.[47]The1931 censuscounted 7,897 people in Acre, 6,076 Muslims, 1,523 Christians, 237 Jews, 51 Baháʼí and 10 Druze.[48]In the1945 censusAcre's population numbered 12,360; 9,890 Muslims, 2,330 Christians, 50 Jews and 90 classified as "other".[49][50]

Acre's fortwas converted into a jail, where members of the Jewish underground were held during their struggle against the Mandate authorities, among themZe'ev Jabotinsky,Shlomo Ben-Yosef,andDov Gruner.Gruner and Ben-Yosef were executed there. Other Jewish inmates were freed by members of theIrgun,whobroke into the jailon 4 May 1947 and succeeded in releasing Jewish underground movement activists. Over 200 Arab inmates also escaped.[51]

1948 Palestine War

In the 1947United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine,Acre was designated part of a futureArab state.On 18 March 4 technicians from the Palestine Electric Company and five British soldiers in their escort were killed while travelling to mend a cable in an RAF camp, when an Arab ambush exploded a mine on the route just outside the Moslem cemetery east of Acre[52]The Haganah responded by blowing up a bridge outside the city and derailing a train.[53]Before the1948 Arab-Israeli Warbroke out, theCarmeli Brigade's 21 Battalion commander had repeatedly damaged theAl-Kabriaqueduct that furnished Acre with water, and when Arab repairs managed to restore water supply, then resorted to pouring flasks oftyphoidanddysenterybacteria into the aqueduct, as part of abiological warfareprogramme. At some time in late April or early May 1948, - Jewish forces had cut the town's electricity supply responsible for pumping water - a typhoid epidemic broke out. Israeli officials later credited the facility with which they conquered the town in part to the effects of the demoralization induced by the epidemic.[54]

Israel's Carmeli forces attacked on May 16 and, after an ultimatum was delivered that, unless the inhabitants surrendered, 'we will destroy you to the last man and utterly,'[55]the town notables signed an instrument of surrender on the night between 17–18 May 1948. 60 bodies were found and about three-quarters of the Arab population of the city (13,510 of 17,395) were displaced.[56]

Israel

Throughout the 1950s, many Jewish neighbourhoods were established at the northern and eastern parts of the city, as it became adevelopment town,designated to absorb numerous Jewish immigrants, largelyJews from Morocco.The old city of Akko remained largely Arab Muslim (including several Bedouin families), with an Arab Christian neighbourhood in close proximity. The city also attracted worshippers of theBaháʼí Faith,some of whom became permanent residents in the city, where the BaháʼíMansion of Bahjíis located. Acre has also served as a base for important events in Baháʼí history, including being the birthplace ofShoghi Effendi,and the short-lived schism between Baháʼís initiated by the attacks byMírzá Muhammad ʻAlíagainst ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[57]Baháʼís have since commemorated various events that have occurred in the city, including the imprisonment ofBaháʼu'lláh.[58]

In the 1990s, the city absorbed thousands of Jews who immigrated from the former Soviet Union. Within several years, however, the population balance between Jews and Arabs shifted backwards, as northern neighbourhoods were abandoned by many of its Jewish residents in favour of new housing projects in nearbyNahariya,while many Muslim Arabs moved in (largely coming from nearby Arab villages). Nevertheless, the city still has a clear Jewish majority; in 2011, the population of 46,000 included 30,000 Jews and 14,000 Arabs.[59]

Ethnic tensions erupted in the city on 8 October 2008 after an Arab citizen drove through a predominantly Jewish neighbourhood duringYom Kippur,leading to five days of violence between Arabs and Jews.[60][61][62]

In 2009, the population of Acre reached 46,300.[63]In 2018Shimon Lankriwas re-elected mayor with 85% of the vote.

Climate

Acre has aMediterranean climate(Köppen:Csa).

| Climate data for Acre (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.9 (78.6) |

29.2 (84.6) |

36.8 (98.2) |

40.3 (104.5) |

42.0 (107.6) |

44.0 (111.2) |

39.9 (103.8) |

34.6 (94.3) |

40.5 (104.9) |

39.9 (103.8) |

34.5 (94.1) |

29.6 (85.3) |

44.0 (111.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.9 (82.2) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.2 (82.8) |

23.9 (75.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

24.5 (76.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.9 (66.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

7.1 (44.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.4 (63.3) |

20.8 (69.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.1 (28.2) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

12.8 (55.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 162.9 (6.41) |

102.0 (4.02) |

53.7 (2.11) |

24.4 (0.96) |

7.4 (0.29) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.1 (0.00) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.5 (0.10) |

27.2 (1.07) |

76.5 (3.01) |

133.9 (5.27) |

591.0 (23.27) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.2 | 9.3 | 6.1 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 5.5 | 10.0 | 49.6 |

| Source:NOAA[64] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Today there are roughly 48,000 people who live in Acre. Among Israeli cities, Acre has a relatively high proportion of non-Jewish residents, with 32% of the population being Arab.[65]In 2000, 95% of the residents in the Old City were Arab.[66]Only about 15% of the current Arab population in the city descends from families who lived there before 1948.[67]

Acre is home to Jews,Muslims,Christians, Druze, and Baháʼís.[68]In particular, Acre is the holiest city of theBaháʼí Faithand receives manypilgrimsof that faith every year.[69]

In 1999, there were 22 schools in Acre with an enrollment of 15,000 children.[70]

Transportation

The Acre centralbus station,served byEggedandNateev Express,offers intra-city and inter-city bus routes to destinations all over Israel. Nateev Express is currently contracted to provide the intra-city bus routes within Acre. The city is also served by theAcre Railway Station,[71]which is on the mainCoastal railway linetoNahariya,with southerly trains toBeershebaandModi'in-Maccabim-Re'ut.

Education and culture

The Sir Charles Clore Jewish-Arab Community Centre in theKiryat Wolfsonneighbourhood runs youth clubs and programs for Jewish and Arab children. In 1990, Mohammed Faheli, an Arab resident of Acre, founded the Acre Jewish-Arab association, which originally operated out of two bomb shelters. In 1993, DameVivien Duffieldof the Clore Foundation donated funds for a new building. Among the programs offered is Peace Child Israel, which employs theatre and the arts to teach coexistence. The participants, Jews and Arabs, spend two months studying conflict resolution and then work together to produce an original theatrical performance that addresses the issues they have explored. Another program is Patriots of Acre, a community responsibility and youth tourism program that teaches children to become ambassadors for their city. In the summer, the centre runs an Arab-Jewish summer camp for 120 disadvantaged children aged 5–11. Some 1,000 children take part in the Acre Centre's youth club and youth programming every week. Adult education programs have been developed for Arab women interested in completing their high school education and acquiring computer skills to prepare for joining the workforce. The centre also offers parenting courses, and music and dance classes.[72]

TheAcco Festival of Alternative Israeli Theatreis an annual event that takes place in October, coinciding with the holiday ofSukkot.[73]The festival, inaugurated in 1979, provides a forum for non-conventional theatre, attracting local and overseas theatre companies.[74]Theatre performances by Jewish and Arab producers are staged at indoor and outdoor venues around the city.[75]

Sports

The city'sfootball team,Hapoel Acre F.C.,is a member of theIsraeli Premier League,the top tier ofIsraeli football.They play in the Acre Municipal Stadium which was opened in September 2011. At the end of the2008–2009 season,the club finished in the top five, and was promoted to the top tier for a second time, after an absence of 31 years.[citation needed]

In the past the city was also home to Maccabi Acre. However, the club was relocated to nearbyKiryat Ataand was renamedMaccabi Ironi Kiryat Ata.[citation needed]

Other current active clubs areAhi Acreand the newly formedMaccabi Ironi Acre,both playing inLiga Bet.Both club also host their matches in the Acre Municipal Stadium.[citation needed]

Landmarks

Acre's Old City has been designated byUNESCOas aWorld Heritage Site.Since the 1990s, large-scale archaeological excavations have been undertaken and efforts are being made to preserve ancient sites. In 2009, renovations were planned for Khan al-Umdan, the "Inn of the Columns," the largest of several Ottoman inns still standing in Acre. It was built near the port at the end of the 18th century by Jazzar Pasha. Merchants who arrived at the port would unload their wares on the first floor and sleep in lodgings on the second floor. In 1906, aclock towerwas added over the main entrance marking the 25th anniversary of the reign of the Turkish sultan,Abdul Hamid II.[76]

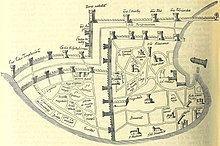

City walls

In 1750,Zahir al-Umar,the ruler of Acre, utilized the remnants of the Crusader walls as a foundation for his walls. Two gates were set in the wall, the "land gate" in the eastern wall, and the "sea gate" in the southern wall. The walls were reinforced between 1775 and 1799 by Jazzar Pasha and survived Napoleon's siege. The wall was thin, at only 1.5 metres (4.9 ft), and rose to a height of between 10 metres (33 ft) and 13 metres (43 ft).[77]

A heavy landdefensive wallwas built north and east to the city in 1800–1814 by Jazzar Pasha and his Jewish advisor, Haim Farhi. It consists of a modern counter-artilleryfortificationwhich includes a thick defensive wall, a drymoat,cannonoutposts and threeburges(large defensive towers). Since then, no major modifications have taken place. The sea wall, which remains mostly complete, is the original wall built by Zahir that was reinforced by Jazzar Pasha. In 1910, two additional gates were set in the walls, one in the northern wall and one in the north-western corner of the city. In 1912, theAcre lighthousewas built on the south-western corner of the walls.[78]

Al-Jazzar Mosque

Al-Jazzar Mosque was built in 1781. Jazzar Pasha and his successor,Sulayman Pasha al-Adil,are both buried in a small graveyard adjacent to the mosque. In a shrine on the second level of the mosque, a single hair fromMuhammad's beard is kept and shown on special ceremonial occasions.

Hamam al-Basha

Built in 1795 by Jazzar Pasha, Acre'sTurkish bathhas a series of hot rooms and a hexagonal steam room with a marble fountain. It was used by the Irgun as a bridge to break into the citadel's prison. The bathhouse kept functioning until 1950.

Citadel of Acre

The current building which constitutes the citadel of Acre is anOttomanfortification, built on the foundation of the citadel of the Knights Hospitaller. The citadel was part of the city's defensive formation, reinforcing the northern wall. During the 20th century thecitadelwas used mainly asAcre Prisonand as the site for agallows.During thePalestinian mandateperiod, activists ofArab nationalistand the JewishZionistmovements were held prisoner there; some were executed there.

Hospitaller fortress

Under the citadel and prison of Acre, archaeological excavations revealed a complex of halls, which was built and used by the Knights Hospitaller.[79]This complex was a part of the Hospitallers citadel, which was included in the northern defences of Acre. The complex includes six semi-joined halls, one recently excavated large hall, a dungeon, arefectory(dining room) and remains of aGothicchurch.

Other medieval sites

Other medieval European remains include theChurch of Saint Georgeand adjacent houses at the Genovese Square (called Kikar ha-Genovezim or Kikar Genoa in Hebrew). There were also residential quarters and marketplaces run by merchants fromPisaandAmalfiin Crusader and medieval Acre.[citation needed]

Baháʼí holy places

There are manyBaháʼíholy places in and around Acre. They originate fromBaháʼu'lláh's imprisonment in theCitadelduring Ottoman Rule. The final years of Baháʼu'lláh's life were spent in theMansion of Bahjí,just outside Acre, even though he was still formally a prisoner of the Ottoman Empire. Baháʼu'lláh died on 29 May 1892 in Bahjí, and theShrine of Baháʼu'lláhis the most holy place for Baháʼís — theirQiblih,the location they face when saying their daily prayers. It contains the remains of Baháʼu'lláh and is near the spot where he died in the Mansion of Bahjí. Other Baháʼí sites in Acre are theHouse of ʻAbbúd(where Baháʼu'lláh and his family resided) and theHouse of ʻAbdu'lláh Páshá(where later ʻAbdu'l-Bahá resided with his family), and theGarden of Ridvánwhere he spent the end of his life. In 2008, theBaháʼí holy placesin Acre and Haifa were added to theUNESCOWorld Heritage List.[80][81]

Archaeology

Excavations at Tell Akko began in 1973.[82]In 2012, archaeologists excavating at the foot of the city's southern seawall found a quay and other evidence of a 2,300-year old port. Mooring stones weighing 250–300 kilograms each were unearthed at the edge of a 5-meter long stone platform chiseled in Phoenician-style, thought to be an installation that helped raise military vessels from the water onto the shore.[83]

Crusader period remains

Under the citadel and prison of Acre, archaeological excavations revealed a complex of halls, which was built and used by the Hospitallers Knights.[79]This complex was a part of the Hospitallers' citadel, which was combined in the northern wall of Acre. The complex includes six semi-joined halls, one recently excavated large hall, a dungeon, arefectory(dining hall) and remains of an ancient Gothic church.[citation needed]

Medieval Europeanremains include theChurch of Saint Georgeand adjacent houses at the Genovese Square (Kikar ha-Genovezim or Kikar Genoa in Hebrew). There were also residential quarters and marketplaces run by merchants fromPisaand Amalfi in Crusader and medieval Acre.[citation needed]

In March 2017, marine archaeologists fromHaifa Universityannounced the discovery of the wreck of a crusader ship with treasure dating back to 1062-1250 AD. Excavators teams also unearthed ceramic bowls and jugs from places asSyria,Cyprusandsouthern Italy.The researchers thought the golden coins could be used as a bribe to boat owners in hopes of buying their escape. Robert Kool of theIAAidentified these 30 coins asflorins.[84][85][86]

International relations

Acre istwinnedwith:

|

|

Notable people

- Joan of Acre(1272–1307), English princess born in Acre

- Isaac ben Samuel of Acre(13th-14th century), Jewish kabbalist who fled to Spain

- As'ad Shukeiri(1860-1940, Palestinian religious scholar political leader and mayor of Acre

- Issam Sartawi(1935-1983), senior member of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)

- Ghassan Kanafani(1936–1972), Palestinian writer

- Raymonda Tawil(born 1940), Palestinian journalist and activist

- Mahmoud Darwish(1941–2008), Palestinian poet and author, widely considered Palestine's national poet; born in the village ofAl-Birwaon the outskirts of Acre.

- Rivka Zohar(born 1948), Israeli singer

- Lydia Hatuel-Czuckermann(born 1963), Olympic foil fencer

- Shai Avivi(born 1964), Israeli actor

- Ron Malka(born 1965), Israeli diplomat and economist who served as the ambassador of Israel to India and non resident ambassador to Sri Lanka and Bhutan, from 2018 to 2021

- Kamilya Jubran(born 1966), Israeli-born Palestinian singer, songwriter, and musician

- Ayelet Ohayon(born 1974), Olympic foil fencer

- Delila Hatuel(born 1980), Olympic foil fencer

- Eliad Cohen(born 1988), Israeli producer, actor, model, entrepreneur, and prominent gay personality

- Avigail Alfatov(born 1996), national fencing champion, soldier, and Miss Israel 2014

In popular culture

- Acre is one of three main settings in the video gameAssassin's Creed.[90][91]

- Thesiege of Acreis depicted at the beginning of theKnightfallTV series.

See also

- District of Acre,Mandatory Palestine

- Armistice of Saint Jean d'Acre(14 July 1941) between the Allies and Vichy France forces in Syria and Lebanon

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Terra Sancta Church

References

Citations

- ^"תוצאות הבחירות המקומיות 2024".www.themarker.com(in Hebrew). March 3, 2024.Retrieved2024-05-07.

- ^ab"Regional Statistics".Israel Central Bureau of Statistics.Retrieved21 March2024.

- ^abcd"Old City of Acre."Archived2020-10-24 at theWayback Machine,UNESCOWorld Heritage Center. World Heritage Convention. Web. 15 April 2013

- ^abcAvraham Negev and Shimon Gibson (2001). "Akko (Tel)".Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land.New York and London: Continuum. p. 27.ISBN978-0-8264-1316-1.

- ^abcPetersen, 2001, p.68Archived2019-03-24 at theWayback Machine

- ^Greene, Roberta R.; Hantman, Shira; Seltenreich, Yair; ʻAbbāsī, Muṣṭafá (2018).Living in Mandatory Palestine: personal narratives of resilience of the Galilee during the Mandate period 1918-1948.New York, NY: Routledge. p. 10.ISBN978-1-138-06898-8.

Acre, too, enjoyed a revival under Daher's rule. The historic port city, which was destroyed by the Mamelukes at the end of the Crusades in the late thirteenth century, was only a small fishing village before Daher arrived. The ambitious ruler, aware of the importance of the port for strengthening his commercial ties with Europe, decided to rebuild it, and it is almost certain that in 1746 he also moved his government center there. He surrounded it with a wall and built a khan, a mosque, a fortress, and the other symbols of authority in the city. Daher's Acre became one of the country's major cities, along with Jerusalem, Nablus, and Jaffa.

- ^Abbasi, Mustafa (2010)."The Fall of Acre in the 1948 Palestine War".Journal of Palestine Studies.39(4): 6–27.doi:10.1525/jps.2010.xxxix.4.6.ISSN0377-919X.JSTOR10.1525/jps.2010.xxxix.4.6.

- ^"History & Overview of Acre".www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-07-10.Retrieved2021-02-28.

- ^abcAcre: Historical overviewArchived2018-09-01 at theWayback Machine(Hebrew)

- ^abcdefghiLipiński (2004),p.304.

- ^Burraburias II toAmenophis IV,letter No. 2

- ^Aharoni, Yohanan(1979).The land of the Bible: a historical geography.Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 144–147.ISBN978-0-664-24266-4.Archivedfrom the original on September 27, 2013.RetrievedOctober 18,2010.

- ^abcdefHead & al. (1911),p. 793.

- ^Judges 1:31

- ^The Guide to Israel,Zev Vilnay,Ahiever, Jerusalem, 1972, p. 396

- ^Jastrow, Marcus(1903)..A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature(Eleventh ed.) – viaWikisource.

- ^ab

Smith, William,ed. (1854–1857). "Ace".Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.London: John Murray.

Smith, William,ed. (1854–1857). "Ace".Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.London: John Murray.

- ^ab"Roman Ptolemais: recent discoveries".Archivedfrom the original on 2018-11-23.Retrieved2018-11-23.

- ^abcdKillebrew (2019),p.50.

- ^Amarna Letter EA245.

- ^Joshua 19:30.

- ^Judges 1:31.

- ^abBecking, Bob (1992):The Fall of Samaria: An Historical and Archaeological Study,Brill,ISBN90-04-09633-7,pp. 31–35

- ^abLipiński (2004),p.306.

- ^ab"2,500-Year-Old Persian Military Base Found In Northern Israel". 2015. Haaretz.Com. Accessed December 26, 2018.[1]Archived2019-09-23 at theWayback Machine.

- ^abPowell, Eric. 2018. "A Persian Military Outpost Identified In Israel – Archaeology Magazine". Archaeology.Org. Accessed December 26, 2018.[2]Archived2018-12-24 at theWayback Machine.

- ^"Acre (Akko) - Overview".

- ^Butcher, 2003; p. 231

- ^Rogers, Guy MacLean (2021).For the Freedom of Zion: the Great Revolt of Jews against Romans, 66-74 CE.New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 532.ISBN978-0-300-24813-5.

- ^Acts 21:7.

- ^Hazlitt, W. (1851)The Classical GazetteerArchived2006-08-22 at theWayback Machinep.4

- ^abSharon, 1997, p.23Archived2016-05-11 at theWayback Machine

- ^abcSharon, 1997, p.24Archived2016-05-11 at theWayback Machine

- ^Le Strange, 1890, p.30

- ^Le Strange, 1890, pp.328–329.

- ^Peters, Edward. The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials. The Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971. (23–90, 104–105, 122–124, 149–151)

- ^abJonathan Riley-Smith, University of Cambridge."A History of the World – Object: Hedwig glass beaker".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on July 9, 2011.RetrievedSeptember 15,2011.

- ^abcdŠārôn, Moše (1997).Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae (CIAP).: A. Volume one.Brill.ISBN978-90-04-10833-2.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-09-11.Retrieved2015-07-01.,page 26

- ^Le Strange, 1890, p.333

- ^Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 192

- ^Note that Rhode, 1979, p.6Archived2019-04-20 at theWayback Machinewrites that the Safad register that Hütteroth and Abdulfattah studied was not from 1595/6, but from 1548/9.

- ^abMaundrell, 1703, pp.53-55

- ^abcSharon, 1997, p.28Archived2016-04-30 at theWayback Machine

- ^Sharon, 1997, p.27Archived2015-09-15 at theWayback Machine

- ^Greene, Roberta R.; Hantman, Shira; Seltenreich, Yair; ʻAbbāsī, Muṣṭafá (2018).Living in Mandatory Palestine: personal narratives of resilience of the Galilee during the Mandate period 1918-1948.New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 6–7.ISBN978-1-138-06898-8.

- ^abKürekli, Recep (NevşehirUniversity)."Socio-Economic Transformation by the Extension of Hedjaz Railway to the Mediterranean Sea: A Case Study on Haifa Qadâ"(PDF).History Studies(in Turkish).doi:10.9737/hist_146(inactive 31 January 2024).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2021-02-28.Retrieved2018-07-07.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - ^Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Acre, p.36

- ^Mills, 1932, p.99

- ^Department of Statistics, 1945, p.4Archived2018-09-28 at theWayback Machine

- ^Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics.Village Statistics, April, 1945.Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p.40Archived2018-09-15 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Acre Jail Break".Britain's Small Wars. Archived fromthe originalon 2008-07-27.Retrieved2008-10-20.

- ^Alon Kadish,The British Army in Palestine and the 1948 War: Containment, Withdrawal and Evacuation,Archived2022-10-08 at theWayback MachineRoutledge2019ISBN978-0-429-84332-7.

- ^Alon Kadish,The British Army in Palestine and the 1948 War: Containment, Withdrawal and Evacuation,Archived2022-10-08 at theWayback MachineRoutledge2019ISBN978-0-429-84332-7.

- ^Benny Morris,Benjamin Z. Kedar,‘Cast thy bread’: Israeli biological warfare during the 1948 WarMiddle Eastern Studies19 September 2022, pages =1-25 p.8.

- ^Benny Morris,1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War,Archived2022-10-08 at theWayback MachineYale University Press2008ISBN978-0-300-14524-3p.166.

- ^Karsh (2010),p. 268

- ^Warburg, Margit (2006).Citizens of the World: A History and Sociology of the Bahaʹis from a Globalisation Perspective.p. 424.

- ^Priestley, Gerda (2008).Cultural Resources for Tourism: Patterns, Processes and Policies.p. 32.

- ^"Locality File".Israel Central Bureau of Statistics.2011. Archived fromthe original(XLS)on 2013-09-23.

- ^Khoury, Jack (October 13, 2008)."Peres in Acre: In Israel There Are Many Religions, But Only One Law".Haaretz.Archivedfrom the original on 16 October 2008.RetrievedOctober 20,2008.

- ^Kershner, Isabel(October 12, 2008)."Israeli City Divided by Sectarian Violence".New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on December 10, 2019.RetrievedOctober 20,2008.

- ^Izenberg, Dan (October 12, 2008)."Police Arrest Acre Yom Kippur driver".The Jerusalem Post.Archived fromthe originalon January 11, 2012.RetrievedOctober 20,2008.

- ^"Table 3 – Population of Localities Numbering Above 2,000 Residents and Other Rural Population"(PDF).Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. December 31, 2009.Archived(PDF)from the original on November 21, 2010.RetrievedFebruary 6,2011.

- ^"World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Acre".National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.RetrievedJanuary 10,2024.

- ^Jerusalem - Facts And Trends 2019Archived2019-07-02 at theWayback Machine,Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. p. 18.

- ^"The Arab population in Israel"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2018-10-03.Retrieved2010-08-03.

- ^Stern, Yoav."For Love of Acre".Haaretz.Archivedfrom the original on 19 October 2008.RetrievedOctober 20,2008.

- ^"Atours".Atours.Retrieved2024-05-11.

- ^Centre, UNESCO World Heritage."Bahá’i Holy Places in Haifa and the Western Galilee".UNESCO World Heritage Centre.Retrieved2024-05-11.

- ^Hertz-Lazarowitz, Rachel (1999). "Cooperative Learning in Israel's Jewish and Arab Schools: A Community Approach".Theory into Practice.38(2): 105–113.doi:10.1080/00405849909543840.JSTOR1477231.

- ^"Israel Railways – Akko".Israel Railways.Archived fromthe originalon 2016-04-20.Retrieved2016-01-10.

- ^"Ambassadors for peace emerging from mixed Israeli neighborhood".ISRAEL21c.2007-03-11.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-01-17.Retrieved2011-04-28.

- ^"Curtain rises over Acre's abundantly diverse Fringe Theater Festival".Haaretz.com.11 October 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 22 January 2012.Retrieved1 October2012.

- ^"Acre Fringe Theatre Festival".akko.org.il.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-09-17.Retrieved2012-10-01.

- ^Birenberg, Yoav (2007-09-30)."Four-day Acre Festival opens Sunday".ynet.Archivedfrom the original on 2013-03-27.Retrieved2012-10-01.

- ^"Unearthing Acre's Ottoman roots".Haaretz.com.4 February 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2009.Retrieved8 March2009.

- ^Kahanov, 2014, p.147.

- ^Rowlett, Russ (2018)."Lighthouses of Israel".The Lighthouse Directory.University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.RetrievedJanuary 24,2019.

- ^ab"Archaeology in Israel – Acco (Acre)".Jewishmag.com.Archivedfrom the original on 6 June 2009.RetrievedMay 5,2009.

- ^"Baha'i Shrines Chosen as World Heritage sites".Baha'i World News Service. July 8, 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 20 November 2008.RetrievedOctober 20,2008.

- ^Glass, Hannah (July 10, 2008)."Israeli Baha'i Sites Recognized by UNESCO".Haaretz.Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2008.RetrievedOctober 20,2008.

- ^Moshe Dothan, Akko: Interim Excavation Report First Season, 1973/4, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 224, pp. 1–48, (Dec., 1976)

- ^"2,000-year old port discovered in Acre".Haaretz.com.18 July 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2012.Retrieved1 October2012.

- ^Hoare, Callum (2020-08-09)."Archaeology breakthrough: Treasure-laden shipwreck find from 'Crusaders' Holy Land flee'".Express.co.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-02-07.Retrieved2020-12-29.

- ^Laskow, Sarah (2017-03-16)."Found: Golden Coins Hidden in a Crusader Shipwreck".Atlas Obscura.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-01-21.Retrieved2020-12-29.

- ^Pruitt, Sarah."Crusader Shipwreck Tells a Golden Knights' Tale".HISTORY.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-12-18.Retrieved2020-12-29.

- ^"Bielsko-Biała – Partner Cities".©2008 Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej.Archivedfrom the original on September 24, 2017.RetrievedDecember 10,2008.

- ^"La Rochelle: Twin towns".www.ville-larochelle.fr.Archivedfrom the original on October 20, 2017.RetrievedNovember 7,2009.

- ^"Pisa – Official Sister Cities".Comune di Pisa.Archivedfrom the original on April 16, 2012.RetrievedDecember 16,2008.

- ^"History Behind the Game – Assassin's Creed Characters".28 September 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-06-12.Retrieved2019-01-08.

- ^Barba, Rick (2016-10-25).Assassin's Creed: A Walk Through History (1189–1868).Scholastic Inc.ISBN9781338099157.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-29.Retrieved2019-08-19.

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923).Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922.Government of Palestine.

- Brody, Aaron; Artzy, Michal (2023).Tel Akko area H: from the Middle Bronze Age to the Crusader period.Leiden; Boston: Brill.ISBN9789004522985.

- Conder, C.R.;Kitchener, H.H.(1882).The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology.Vol. 2. London:Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945).Village Statistics, April, 1945.Government of Palestine.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-04-02.Retrieved2016-06-04.

- Hadawi, S.(1970).Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine.Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived fromthe originalon 2018-12-08.Retrieved2016-06-04.

- Head, Barclay; et al. (1911),"Phoenicia",Historia Numorum(2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 788–801,archivedfrom the original on 2021-03-01,retrieved2018-11-23.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977).Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century.Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft.ISBN978-3-920405-41-4.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-10-14.Retrieved2018-12-10.

- Kahanov, Yaacov; Stern, Eliezer; Cvikel, Deborah; Me-Bar, Yoav (2014). "Between Shoal and Wall: The naval bombardment of Akko, 1840".The Mariner's Mirror.100(2): 147–167.doi:10.1080/00253359.2014.901699.S2CID110466181.

- Karsh, Efraim(2010).Palestine Betrayed.New Haven: Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-12727-0.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2019),"Canaanite Roots, Proto-Phoenicia, and the Early Phoenician Period,ca.1300-1000 bce ",The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean,Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.39–57,ISBN978-0-19-765442-2.

- Le Strange, G.(1890).Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500.Committee of thePalestine Exploration Fund.

- Lipiński, Edward (2004),Itineraria Phoenicia,Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta,No. 127,Studia Phoenicia,Vol. XVIII, Leuven: Peeters,ISBN978-90-429-1344-8.

- Maundrell, H.(1703).A Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem: At Easter, A. D. 1697.Oxford: Printed at the Theatre.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932).Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas.Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Pappé, I.(2006).The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine.London and New York: Oneworld.ISBN978-1-85168-467-0.

- Peters, E.(1971).The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials. The Middle Ages Series.Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.(23–90, 104–105, 122–124, 149–151)

- Petersen, Andrew (2001).A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology).Vol. I.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-727011-0.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-29.Retrieved2018-12-15.

- Philipp, Thomas (2001).Acre -The rise and fall of a Palestinian city, 1730-1831.Columbia University Press.ISBN978-0-231-12326-6.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-06-05.Retrieved2015-07-01.

- Pococke, R.(1745).A description of the East, and some other countries.Vol. 2. London: Printed for the author, by W. Bowyer.

- Pringle, D.(1997).Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0521-46010-7.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-06-08.Retrieved2015-07-01.(pp.16Archived2015-09-24 at theWayback Machine-17)

- Riley-Smith, J.(2010),A History of the World-Object: Hedwig glass beaker,BBC,archivedfrom the original on 2019-05-29,retrieved2010-06-25

- Sharon, M.(1997).Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, A.Vol. 1. BRILL.ISBN978-90-04-10833-2.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-12-21.Retrieved2018-12-10.

- Torstrick, Rebecca L. (2000).The Limits of Coexistence: Identity Politics in Israel.The University of Michigan Press.ISBN978-0-472-11124-4.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-11-26.Retrieved2015-07-01.

External links

- Acre Municipality official websiteArchived2016-09-19 at theWayback Machine

- Official website of the Old City of Acre

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 3:IAA,Wikimedia commons

- Orit Soffer and Yotam Carmel,Hamam al-Pasha: The implementation of urgent ( "first aid" ) conservation and restoration measures,Israel Antiquities Site–Conservation Department

- Picart map of Old Acre, 16th century.Eran Laor Cartographich Collection, The National Library of Israel.

- World Heritage Sites in Israel

- Acre, Israel

- Arab Christian communities in Israel

- Baha'i holy cities

- Castles and fortifications of the Knights Hospitaller

- Cities in Northern District (Israel)

- Coloniae (Roman)

- Hebrew Bible cities

- Holy cities

- Mediterranean port cities and towns in Israel

- Mixed Israeli communities

- New Testament cities

- Phoenician cities

- Achaemenid ports

- Roman towns and cities in Israel

- Talmud places

- Ottoman clock towers

- Clock towers in Israel

- Archaeological sites in Israel

- Ancient sites in Israel

- Medieval sites in Israel

- Seleucid colonies

- Ptolemaic colonies